Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library, The George Washington University Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library, The George Washington University

Health Sciences Research Commons Health Sciences Research Commons

Doctor of Nursing Practice Projects Nursing

Spring 2020

Using Five Wishes to Improve Advance Care Planning in A Using Five Wishes to Improve Advance Care Planning in A

Maryland Primary Care Practice Maryland Primary Care Practice

Amanda Bridges, MSN, ACNP-BC

George Washington University

Follow this and additional works at: https://hsrc.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/son_dnp

Part of the Nursing Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Bridges, MSN, ACNP-BC, A. (2020). Using Five Wishes to Improve Advance Care Planning in A Maryland

Primary Care Practice.

,

(). Retrieved from https://hsrc.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/son_dnp/59

This DNP Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Nursing at Health Sciences Research

Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctor of Nursing Practice Projects by an authorized administrator

of Health Sciences Research Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected].

Running head: FIVE WISHES 1

Using Five Wishes to Improve Advance Care Planning in A Maryland Primary Care Practice

Amanda Bridges MSN, ACNP-BC

The George Washington University

March 21, 2020

DNP Primary Advisor: Richard Ricciardi, PhD, CRNP, FAANP, FAAN

DNP Second Advisor: Mary-Michael Brown, DNP, RN

FIVE WISHES 2

A Project Presented to the Faculty of the School of Nursing

The George Washington University

In partial fulfillment of the requirements

For the Degree of Doctor of Nursing Practice

By

Amanda Bridges, ACNP-BC

Approved: Richard Ricciardi, PhD

Approved: Mindi Cohen, DO

Approval Acknowledged:

Director DNP Scholarly Projects

Approval Acknowledged: Dr. Mercedes Echevarria

Assistant Dean for DNP Program

Date: April 4, 2020

Approved:

ary

Micha

Brown,

DNP

FIVE WISHES 3

Table of Contents

Cover Page.………………………………………………………………………………….....

1

Table of Content………………………………………………………………………………..

2

Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………

5

Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………..

7

Background and Significance…………………………………………………………………..

8

Needs Assessment……………………………………………………………………………....

11

Problem Statement……………………………………………………………………………...

14

Aims and Objectives……………………………………………………………………………

14

Review of the Literature………………………………………………………………………..

15

Evidence Based Practice Model………………………………………………………………..

18

Methodology…………………………………………………………………………………....

19

Setting……………………………………………………………………………………

Study Population………………………………………………………………………....

Subject Recruitment……………………………………………………………………...

Consent Procedure……………………………………………………………………….

Risks/Harms……………………………………………………………………………...

Subject Costs and Compensation………………………………………………………...

Study Interventions………………………………………………………………………

Outcomes to be Measured………………………………………………………………..

Project Timeline………………………………………………………………………….

Resources Needed…………………………………………………………………….….

21

21

22

22

23

23

24

25

26

27

FIVE WISHES 4

Results……….…………………………………………………………………………………

27

Discussion……………………………………………………………………………………...

30

Sustainability and Future Scholarship………………………………………………………….

32

Conclusion…..……………………………………………………………………………….…

32

References……………………………………………………………………………………...

36

Appendices….………………………………………………………………………………….

40

Literature Review…….….……………………………………………………………….

Five Wishes Questionnaire……………………………………………………………….

Five Wishes Consent……..……………………………………………………………….

Shared Decision Making Tool…..…….………………………………………………….

40

52

53

54

Kiosk ACP Questions for EHR.…………………………………………………………..

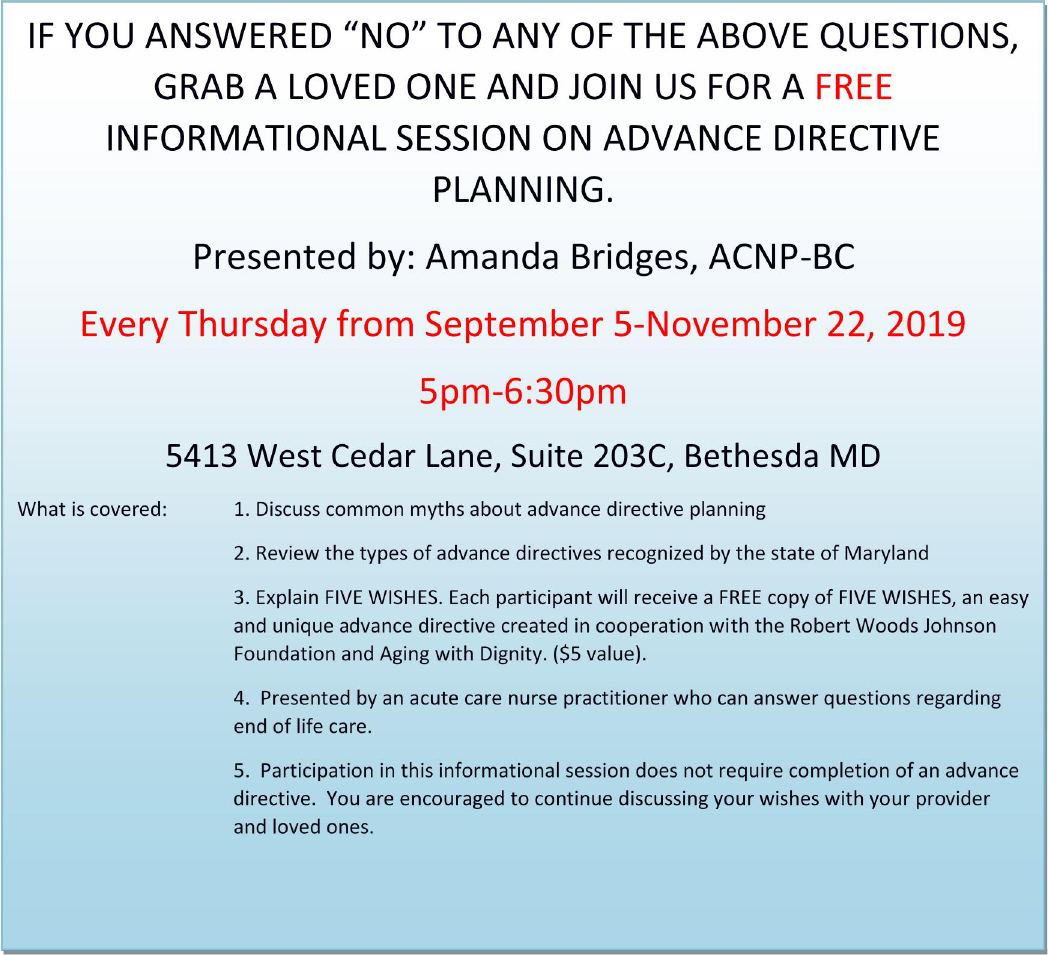

Five Wishes Invitational Flyer……..….………………………………………………….

Data Definitions/Demographics………..…………………………………………………

IRB Documents…………………………..……………………………………………….

DNP Team Signature Sheet………………......…………………………………………..

55

56

57

66

68

FIVE WISHES 5

Tables and Figures

Table 1

Cost and Benefit Analysis……………………………………………….

58

Table 2

Evaluation….…………………………………………………………….

58

Table 3

Table 4

Table 5

Data Analysis…………………………………………………………….

Data Definitions………………………………………………………….

Variable Analysis Table………………………………………………….

60

63

63

Figure 1

Revised Johns Hopkins Model…………….…………………………….

33

Figure 2

Methodology Map….…………………………………………………….

34

Figure 3

Project Timeline...……………………………………………………….

35

FIVE WISHES 6

Abstract

Background

Engagement in Advance Care Planning (ACP) at this primary care practice is minimal with no consistent

process to document existing advance directives (AD) or educate about ADs.

Objectives

The purpose of this QI project was to increase ACP discussions, improve documentation of existing ADs and

educate about Five Wishes.

Methodology

Adults, at each office encounter, were asked three kiosk questions: Do you have an AD, know what it is and

want to discuss ACP? The responses were uploaded to the EHR to become an evidence backed, visual

reminder. Affirmation of existing ADs were descriptively documented. ACP engagement was analyzed by

chi square comparing responses to the questions and provider engagement in ACP. Everyone was invited to

a Five Wishes seminar and given the same questionnaire pre and post with mean responses assessed via a

paired t-test.

Results

The 1037 participants were mostly, employed, white, married and averaged age 52. After 12 weeks, 90 ACP

discussions took place compared to 6 discussions prior to implementation (p<0.001). At the seminar, 21

people had mean result with mixed statistically significance. The questions regarding value of Five Wishes

and discussing ACP were statistically significant (p<0.05). The total number of existing ADs was 23% of

1037 encounters.

FIVE WISHES 7

Conclusion

Engagement in ACP discussions improved by both asking about interest and creating EHR reminders. The

kiosk-initiated process makes this project sustainable and normalize ACP discussions. Five Wishes does not

meet legal requirements for an AD in every state and future policy should focus on full legalization.

FIVE WISHES 8

Using Five Wishes to Improve Advance Care Planning in a Maryland Primary Care Practice

An advance directive (AD) is a legal document intended to assist loved ones and medical

providers with end of life wishes when a person is unable to state their dying preferences for

medical care. In the state of Maryland, there are two forms that meet the legal requirements for

an AD: (a) Maryland Advance Directive: Planning for Future Health Care Decisions and (b) Five

Wishes (Advance Directive, n.d). The Maryland AD outlines both the designated person to

make medical decisions as well as several back up designations. Comfort and medical treatment

options are also covered along with the designation of organ donation and funeral arrangements

(Maryland Attorney General, n.d.).

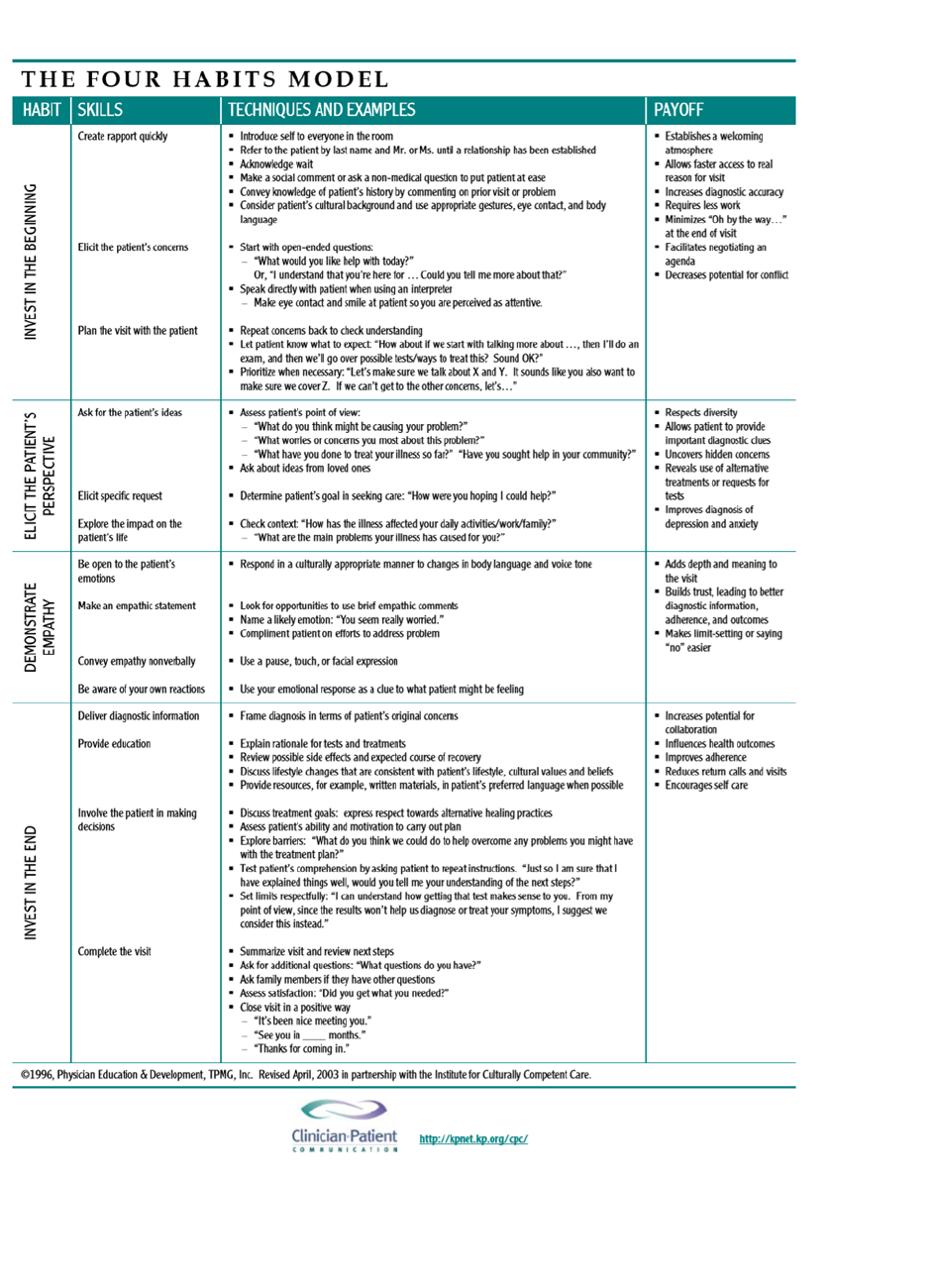

Five Wishes is an AD that was developed by the nonprofit organization, Aging with

Dignity, and supported by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (Aging with

Dignity, 2012). This AD addresses the legal questions of health care power of attorney and

medical care desires for end of life care but also includes questions to address spirituality,

comfort, forgiveness and final wishes (Aging with Dignity, 2012). The five “wishes” are:

1. The person I want to make care decisions for me when I can’t

2. The kind of medical treatment I want

3. How comfortable I want to be

4. How I want people to treat me

5. What I want my loved ones to know

This project focused on improving advance care planning in a primary care practice with Five

Wishes.

FIVE WISHES 9

The process of completing an AD is often done in conjunction with a medical provider.

It is expected that a patient’s provider can guide decisions and answer questions about ACP.

ACP involves completing a chosen AD that is legally recognized by the state of residency. ADs

are instrumental in communicating patients’ wishes regarding end of life care and prevents loved

ones from the burden of making big medical decisions on someone else’s behalf. In addition,

ACP can improve the quality of end of life care and substantial decrease unnecessary hospital

admissions. However, the medical community, especially primary care, is vital to facilitating the

completion of this important document and thus efforts are needed to proactively engage primary

care providers and patients in having ACP discussions.

Background and Significance

The requirement for healthcare providers to facilitate ACP was established by the 1991

Patient Self-Determination Act (PDSA) which requires that any healthcare facility that receives

federal funding should discuss, educate, and facilitate the implementation of ADs (Douglas &

Brown, 2002). This established ADs as a standard of care. Recent advancements in healthcare

policy to further legislate AD use has had limited success. In 2009, the Affordable Care Act

(ACA) and the Advanced Planning and Compassionate Care Act both included efforts to

improve AD implementation by reimbursing physicians for ACP (Whelan, 2013).

Unfortunately, the factual content of the policy and myths surrounding potential “death panels”

resulted in removal of this aspect from the ACA (Whelan, 2013).

By the year 2030, all the baby boomers will have reached the age of 65 or older (Van

Wert, 2018), which will further increase the demand for an aging community to need ACP. This

places more pressure on primary care to develop a systematic process to facilitate ACP

discussions. To address this concern, Medicare ruled in November 2015 that ACP could be

FIVE WISHES 10

billed by providers as a Current Procedure Terminology (CPT) code for up to 30 minutes of

discussion starting January 1, 2016 (Verhovshek, 2016). Reimbursement for the first 30 minutes

of ACP equates to approximately $75 and an additional $70 for each additional 30 minutes

(Verhovshek, 2016). This reimbursement does not require the completion of an AD and can be

billed by any qualifying provider at each encounter where ACP is discussed, regardless of the

number of discussions (Verhhovshek, 2016). This was intended to create an incentive for

providers to improve ACP discussions, but financial incentives alone have not changed the

medical culture of discussion ACP.

According to a retrospective review of Medicare ACP billing in New England, less than

1% of the 2016 Medicare claims involved ACP (Pelland, Morphis, Harris & Gardner, 2019).

Providers are either not taking advantage of the reimbursement potential or have not effectively

created a process to discuss ACP in their medical practice. Likely, both reasons explain the lack

of implementation.

According to a 2014 “end of life” care survey, patients over the age of 18 years old were

surveyed regarding perception of end of life needs, discussions with loved ones about their end

of life desires, and existing advance directives (Rao, Anderson, Lin & Laux, 2014). Not

surprisingly, those of advanced age and with terminal diseases were more likely to have an AD.

Those who did not feel they had any end of life concern were less likely to complete an AD but

most of the participants surveyed lacked AD awareness (Rao, Anderson, Lin & Laux, 2014).

This lack of awareness highlights the need for primary care to proactively address AD education

in all patients before they become terminally ill or of advanced aged.

Advance care planning research to support AD use varies in design and often cannot

directly address the variable of cost due to ethical concerns. However, in 2018, Bond and

FIVE WISHES 11

colleagues (2018) evaluated ACP, retrospectively, in an Accountable Care Organization (ACO)

by comparing two groups of Medicare patients: those who had an AD at death versus those who

did not have an AD at death (Bond et. al., 2018). The authors reported that the AD group had a

nearly $10,000 adjusted savings compared to the control group (Bond et al., 2018). The authors

surmised that most of the cost savings to Medicare was in the reduction of inpatient admissions

(Bond et al., 2018). Saving money is not the main goal of any end of life discussion but reducing

unnecessary hospital admissions is a valuable goal. The discussion of ACP in terms of cost

savings is really a discussion about unnecessary hospital admissions.

There are three common reasons why people do not complete an AD: patients either

assume their loved ones know what they want, the patients do not understand ADs, or they fear

an AD will withhold medical care (Splendore & Grant, 2017). In general, the people who are

most likely to have an AD, are those with a terminal illness, of non-Hispanic, white race and

those of a higher socioeconomic status (Rao et al., 2014). According to the 2003 report on health

literacy from the US Department of Health and Human Resources, less than 13% of adults are

“proficient in understanding basic health information” with an even higher percentage of

Hispanic and elderly with even lower levels of literacy (n.d). The issue of health literacy

highlights the need for an ACP process in primary care that is repetitive, includes everyone and

has adjunctive educational options.

Shared decision making (SDM) is a core concern for this project. In order to improve

provider engagement in ACP, it is necessary for providers to have strong shared decision-making

skills. In a 2019 randomized control trial on the benefits of shared decision-making tools and

lung cancer screening, a subset of the LSUT (Lung Screening Uptake Trail) were assigned to two

methods of education on lung cancer screening. One group received the booklet alone and the

FIVE WISHES 12

other group received both the booklet and a video with a provider giving the education. In the

end, both groups had better understanding of lung cancer screening but the video group, showed

an even greater understanding (Ruparel, et.al, 2019). This highlights the value of various

mediums to address SDM with patients. This project addressed SDM with the provider via a

SDM educational brochure and a brief SDM oral presentation.

These factors are the historical aspects of ACP that were considered for this ACP

project. To successfully educate patients and reduce misconceptions, providers must be capable

of successful engagement in SDM. The information on ACP must be explained to patients via

various methods. Because reimbursement alone is not enough to encourage providers to have

ACP discussions, a simple, systems process is needed. Lastly, repeated opportunities for patients

to discuss ACP will facilitate normalization of ACP in primary care.

Needs Assessment

The previous process of addressing ACP at this project’s primary care practice, was done

inconsistently, by only a few providers during a Medicare annual wellness visit. Even when

patients had an AD, there was no consistent process to designate that an AD existed. In a review

of ACP discussions and CPT billing of ACP in Medicare patients for 2018, only 23 out of

approximately 3,000 enrolled Medicare patients had CPT billing for ACP in the 2018 calendar

year, for the entire practice (ECW, 2019). This primary care practice has office locations in

Maryland, Virginia and the District of Columbia. The wide geographical variability required

that this project start at one location in Maryland, over 12-weeks with future expectations to

implement this ACP project practice wide.

FIVE WISHES 13

A Strengths- Weakness-Opportunities-Threats (SWOT) analysis was done to evaluate the

feasibility of this ACP project. Strengths and opportunities for this project are substantial. The

strengths include an abundance of owner support for improving ACP. Employees are skillful

and cooperative and lastly, there is a practice wide EHR, which allows for data mining and

systematic processing. Additional strengths include three information technology (IT) support

staff who have various levels of IT responsibilities; one IT staff is a nurse practitioner. This

nurse practitioner assisted with data mining.

Weaknesses to this project include geographical distances between offices as some staff

who are instrumental to this project are located at other offices and communicate mainly via

email and phone. This distance did impede efficient and timely communication. Much of the

success of this project required both provider and ancillary staff “buy in” to ensure practice

change. The providers ability to successfully participate in SDM was not as significant a

weakness as expected. Medical assistant “buy in” was the most substantial weakness to this

project’s success. The ability of patients to use technology, like an electronic kiosk, was a

weakness. Given the Five Wishes educational seminars was provided only in English, there

were limited opportunities to educate non-English speaking patients about this specific AD.

However, copies of Five Wishes were available in two other languages, Russian and Spanish, for

providers and staff who speak the patient’s native language.

Opportunities for this project included continued practice growth through recent

acquisition of additional practice locations in Maryland and an alignment with a larger hospital

healthcare system to improve community resources. Given the expected volume of the aging

baby boomers, this project could model a successful ACP process for other primary care

practices to implement.

FIVE WISHES 14

The greatest threat to this project was the stigma of discussing death. Not surprisingly,

most patients did not want to discuss ACP. In general, Americans are often in denial about

death and do not plan for dying (Life in the USA, n.d). This is likely hindered by poor media

portrayal of dying and prior political influences on the topic of ACP.

There was a total of three providers, two physicians and one nurse practitioner, who

participated in this project at the Maryland location. The nurse practitioner works at this practice

location four days per week. Both physicians are the practice owners and see patients at other

office locations. These two physicians work at this location, one to two days per week. The

project utilized the front desk secretary and three medical assistants who disseminated

information and documented data in the EHR. Apart from one medical assistant and the front

desk secretary, all the other medical assistants rotate to other office locations throughout the

week. Having rotating staff members exposed to this QI project facilitates the opportunity to

implement this project at other offices. These staff members can become future super trainers

for other offices.

The practice’s strategic plan is to provide comprehensive care to all patients with a

substantial focus on care coordination for the vulnerable and Medicare population. No previous

attempts to implement a formal ACP program has been tried at this practice. This ACP QI

project upholds the paradigm of comprehensive care and service to the aging population by

improving holistic medical management.

Problem Statement

The problems addressed by this project were provider engagement in ACP,

documentation of existing ADs, and educating patients about an alternative AD known as Five

FIVE WISHES 15

Wishes. To increase ACP discussions, a process was needed to engage all patients and

encourage providers to initiate an ACP discussions. In general, most patients were not interested

in ACP. However, this was not assumed based on age or medical history and thus everyone was

asked about interest in discussing ACP, at each office encounter. The benefit of asking everyone

at every encounter was to improve patients’ familiarity with the topic. Familiarity with the topic

of ACP could result in the now 18-year-old understanding the importance of ACP when older

and chronic disease develops. Patient responses to the question about existing AD resulted in

consistent documentation in the EHR. Lastly, this project was supplemented with the additional

measure of an educational seminar, open to everyone, to learn more about a unique AD called

Five Wishes.

Aims and Objectives

The aims and objectives for this project were as follows. The first aim was to increase

provider engagement in ACP. The first aim was assessed objectively by the total number of

encounters that documented a discussion of ACP by ICD-10 code at the end of the 12- week

project compared to both the number of providers who engaged in ACP discussion in the 12-

weeks prior to the project and patient responses to interest in ACP. The second aim was to

create a process to document existing ADs. This was assessed by percentage of existing ADs

noted in the EHR over 12-weeks. The third aim was to provide a seminar that successfully

educated patients about the value of ACP and an alternative AD, known as Five Wishes.

Education of Five Wishes was evaluated by patient responses to a Likert scaled questionnaire

given pre and post seminar at each weekly session over 12-weeks. Each patient answered the

same questionnaire pre and post seminar (Appendix B) to assess their before and after perceived

FIVE WISHES 16

value of ACP and Five Wishes, specifically. The questionnaire was adapted from previous,

similar research on the educational value of a Five Wishes seminar (Hinderer, 2014).

Review of Literature

A literature review took place between February to June of 2019 (Appendix A). Using

the CINAHL database, research was evaluated using the search terms “advance care planning,”

and “end of life care” and the inclusion criteria of all adults, academic journals and research that

was less than 5-year-old. This resulted in 54 articles for evaluation. Articles that focused on a

specific subpopulation or in an inpatient setting were excluded. Ultimately, five articles of the

54 were accepted both as relevant to outpatient ACP and of acceptable quality. Another separate

CINAHL search was conducted specifically using the terms “Five Wishes” including only

adults, and academic journals in the past five years. This resulted in only three articles. One

article was excluded based on its focus on a specific subset of seriously ill patients. The two

remaining articles were similar educational seminars to this research design and thus used as

examples to establish the Five Wishes educational seminar.

Lastly, CINAHL was used again to search the terms “shared decision making”, “and”,

“tools or instruments”, “physicians or doctors”. This search excluded research outside of the

United States and included adults, academic journals, English language with an extension to

eight years (2011- 2019). This resulted in 18 articles. The extension beyond the standard five

years was needed to capture a simple, evidence-based tool that addressed SDM in providers.

The articles were all reviewed for both content and quality, with the most applicable to primary

care and of the best quality used for this analysis.

A resource librarian was consulted for assistance with obtaining permission to use the

Advance Directive Attitude Survey (ADAS). The attempt to use ADAS was unsuccessful.

FIVE WISHES 17

Excerpts of ADAS were publicly available and noted in various articles and complied to create

the Five Wishes questionnaire.

The quality of the articles was assessed using the Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence Based

Practice Model and Guidelines (Dearholt & Dang, 2018). The articles’ assessed quality is noted

in Appendix A. This assessment tool qualifies research based on a scale from I-V with

subdivided criteria of a, b and c signally high, good and low quality. Level I research is

strongest and defined as a randomized control trials with level V representing experiential and

non-evidence-based data (Dearholt & Dang, 2018).

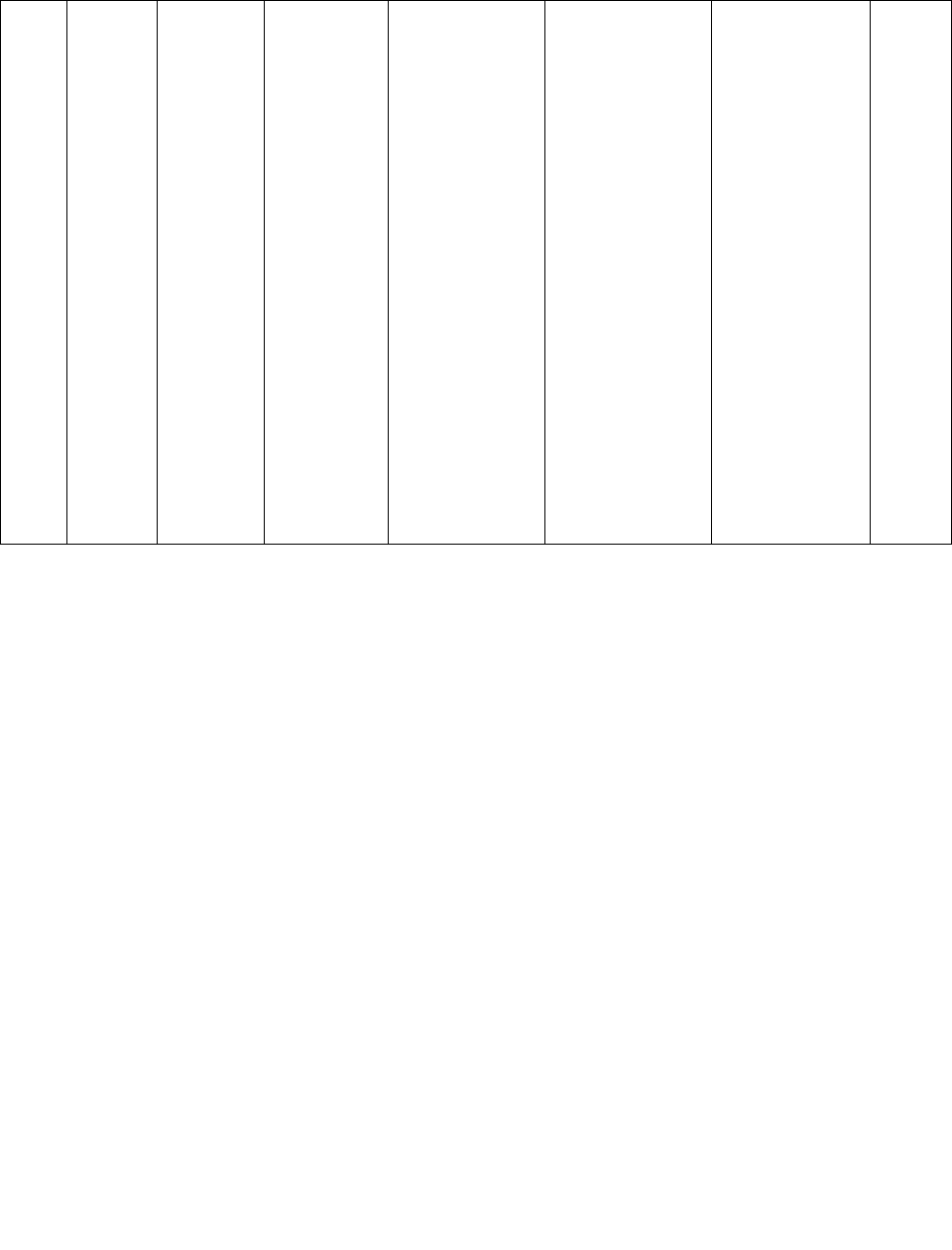

The evidence from the following articles supported the methodology to address the aim

of improving provider engagement in ACP discussions. First, providers must have the ability to

engage in SDM to improve ACP. Jensen and associates (2011) supported the value of SDM by

studying the effects of training physicians on the Four Habits of Communication (Appendix D)

versus no training. These authors noted that, even with minimal training, patients’ perceptions of

SDM improved for providers who had some communication training. Although an older article,

this article was included to highlight the value of, even minimal training, to improve providers’

SDM ability (2011). Forcino and others (2017) provided a valid tool to assess patient’s

perceptions of a provider’s ability to engage in SDM. The CollabRATE shared decision-making

tool is a short three question tool with validity in numerous geographical primary care settings

(Forcino, et. al., 2017). This tool did not fit into my methodology but highlights the value of

SDM. Hayek and associates (2014) indicated that a provider’s ability to successfully engage in

shared decision making with patients is a vital aspect to ACP discussions.

Next, a team approach with EHR reminders lends itself to more successful ACP and

satisfaction with end of life care. Reinhardt and associates described a team approach to

FIVE WISHES 18

discussing end of life care and its positive impact on the loved ones who managed a patient’s end

of life wishes. Reinhardt et al. (2014) highlighted how ongoing conversations and ongoing

discussions improved AD documentation and ultimately, family members felt better about their

loved ones end of life care when an AD was in place (2014). Hayek and colleagues (2014)

offered strong evidence that provider reminders, especially in an EHR, were more successful in

improving AD implementation compared to no reminders. These authors concluded a direct

association between the number of reminders and number of AD completed (2013

The aim of improving education about Five Wishes was evaluated through research

results specifically about Five Wishes Educational Workshops. The articles that evaluated Five

Wishes education did not have a direct impact on the number of ADs implemented, however, all

articles validated the value to patient education. Hinderer & Lee (2014) and Splendore & Grant

(2017) developed educational programs to teach community adults about Five Wishes. Both

programs used community workshops to deliver the education. Neither program was associated

with a specific primary care practice. Both articles used a variation of a well-validated

questionnaire called the Advance Directive Attitude Survey (ADAS) to evaluate their

programs. As previously noted, attempts to obtain permission to use the full ADAS tool were

unsuccessful. Select questions from ADAS were reported in the article and used to create the

questionnaire for this project. Splendore & Grant’s Five Wishes educational seminar did report

an improvement in the patients’ perceived importance of ACP (2017). This article was

sponsored by the creators of Five Wishes. Hinderer & Lee (2014) used a community outreach

project to educated adults about Five Wishes. The sampling of people in this study did not

change their attitude about ACP but did statistically confirm that the educational program was

perceived as valuable to the participants based on the ADAS tool. This highlights that it takes

FIVE WISHES 19

more than just education to successfully implement an ACP program in clinical practice

(Hinderer, & Lee, 2014).

Evidence-based Practice (EBP) Translation Model

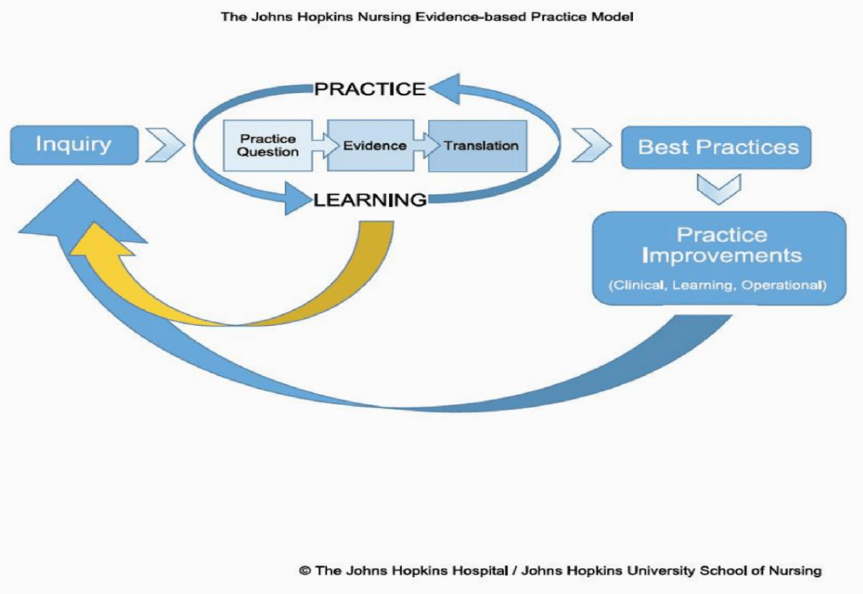

The revised Johns Hopkins Model (JHM) (Figure 1) was used as the evidence-based

translation model (Dearholt & Dang, 2018). This model was chosen for its inclusion of both

internal and external factors to influence best practices. This is especially important in ACP

where multiple internal and external factors impact implementation. An example of internal

factors includes a providers’ SDM ability to discuss ACP and an external factor is our societal

paradigms about death and dying. The process starts with an inquiry into the problem, followed

by the Practice, Evidence and Translation (PET) process to assess the question, gather the

evidence and translate the information into practice, all while learning new knowledge (Dearholt

& Dang, 2018).

The initial process of inquire started with identifying the need for ACP by assessing the

number of patients in the practice who have a documented discussion with their provider about

ACP. Next, practice owners’ interest in improving ACP was determined. Together, sufficiency

information supported the value of this project. This was then followed by gathering research

that was evaluated for quality, as mentioned, via Johns Hopkins Evidence Based Research

assessment. The research supported the value of improving shared decision making in

providers. Evidence also guided the internal and external influences on ACP. This information

was used to mitigate some of the research-based obstacles to implementing a ACP

process. Based on this information, a process was developed that teaches providers about

shared decision making and a systemic clinical process was developed to improve providers’

opportunities to discuss ACP with patients and document existing ADs. In addition, the

FIVE WISHES 20

research on other Five Wishes educational programs was modeled to address patient education

about this specific AD. During implementation, the internal and external influences guided the

teaching aspects that promote or inhibit implementation of ACP discussions, so practice change

can be successful.

Methodology

This is a quality improvement project that improved provider participation in ACP

discussions, documentation of existing ADs and education about the specific AD known as Five

Wishes. The evidence from prior research was incorporated into the methodology. The process

started with educating providers on shared decision making (SDM). Each provider was asked to

read an educational paper on how to improve their SDM ability (Appendix D). A short power

point presentation of SDM was given to all providers in the practice at our practice meeting prior

to implementation. Providers’ compliance with reading this educational paper on SDM was self-

reported. Patient recruitment to participate in ACP was through convenience sampling of those

who had an appointment at the Maryland office during the study implementation time

frame. Upon arriving at the appointment, all patients were asked three screening questions

about interest in discussing ACP via an electronic tablet enabled kiosk which was then uploaded

to the EHR by the medical assistant (Appendix E). A paper invitation to attend the informational

seminar on Five Wishes was given to every patient by the secretary (Appendix F). In addition, a

large electronic poster advertising the Five Wishes Seminar was on display in every exam room.

This electronic poster had the same information about the Five Wishes program date, time and

content (Appendix F). In addition, providers were asked to encourage all patients and their

family members to attend the Five Wishes seminar. Anyone could attend the Five Wishes

Seminar. After informed consent and a pre-seminar questionnaire, a 30-minute video created by

FIVE WISHES 21

Aging with Dignity was shown and followed by an informal question/answer session with an

eacute care nurse practitioner. The participants then completed the same questionnaire post

seminar. The questionnaire responses were via Likert scale that corresponded with perceived

value of both Five Wishes and ACP.

The following concepts noted in prior research were used in implementation. First,

shared decision making (SDM) was addressed with a short educational flyer and power point

presentation. Next, EHR documentation of patients who affirmed an existing AD was

consistently noted. Then, the patients’ responses to interest in an ACP discussion were uploaded

directly to the encounter note, in the EHR, creating an evidence backed, visual reminder

(Appendix E). If an ACP discussion was not possible during that office visit, patients were

asked to schedule another appointment to specifically discuss ACP or attend the educational

seminar on Five Wishes.

This project started on September 3, 2019 at a Maryland office location and ended

November 22, 2019. All data was mined through the EHR known as E-Clinical Works (ECW)

with the seminar evaluated by paper questionnaire responses (Appendix B). The Five Wishes

seminar was modeled after similar educational seminars noted in the literature review and a

similar questionnaire developed based on published exert of the ADAS questionnaire (Appendix

B). As noted, permission to use the ADAS tool was unsuccessful, but elements of this tool were

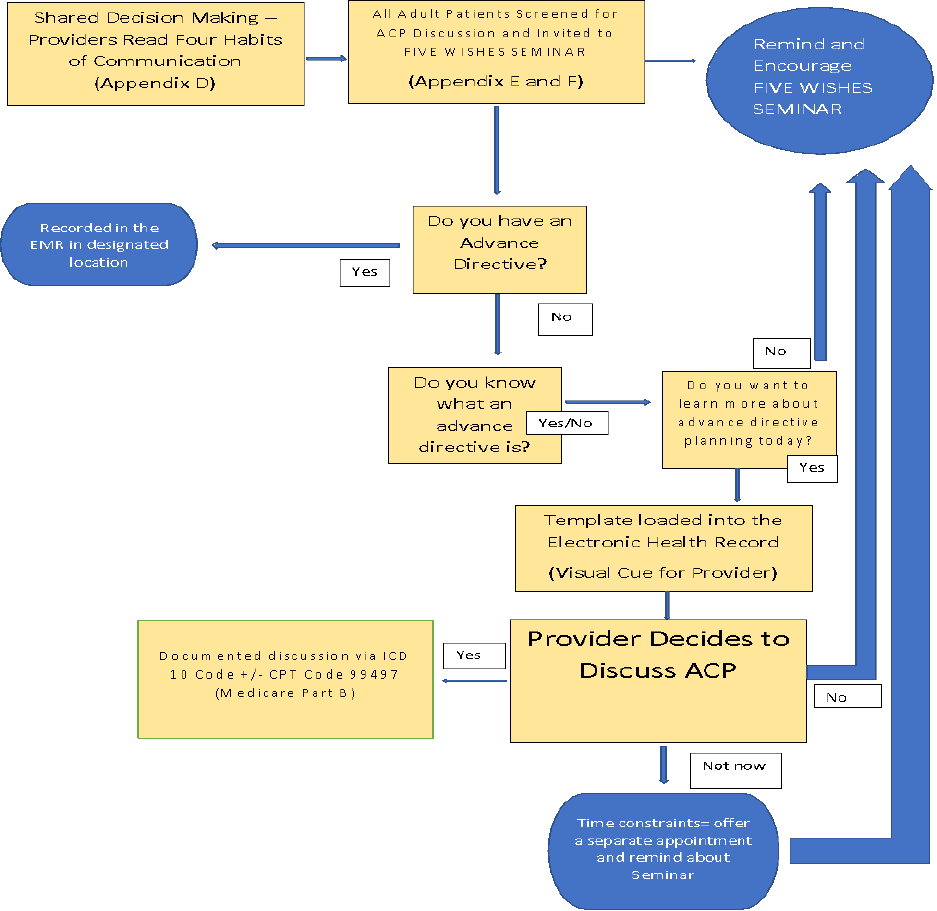

available in the literature review and used in creating the questionnaire (Appendix B). Figure 2

summarizes the project implementation process.

Setting

The setting for this QI project is a primary care practice in Maryland. The location of this

practice is in one of the highest educated cities in the United States and is situated just outside

FIVE WISHES 22

the nation’s capital, Washington, DC (Raghaven, D., 2014). The building for this practice

location typically accommodates only two providers and averages approximately 20 patient

encounters per day. The office location provides free parking and is conveniently located near

public transportation. The building is handicap accessible.

Study Population

There were two study groups evaluated. The first group consisted of a convenience

sampling of patients who met inclusion criteria and were seen at this office location between

September 2019 until November 2019. The second group were patients, loved ones and friends

who voluntarily attended the Five Wishes seminar during the implementation period. Inclusion

criteria for both groups were adults, defined as over the age of 18-year-old, of any race, gender,

or socioeconomic status. Patients who were blind or diagnosed with advanced dementia without

a designated power of attorney were excluded. All patients, family and friends were invited to

attend a free, weekly educational seminar on the AD known as Five Wishes. It was estimated

that approximately 1,200 patients would be offered ACP and invited to the Five Wishes Seminar

during the study period.

Patients who were seen at this location were mostly native English speaking, non-

Hispanic whites, however Russian and Spanish speaking patients are also seen at this

location. The Russian and Spanish speaking patients had varying fluency in English. Most non-

English speaking patients were seen by a provider who speaks their native language, or a native

speaking medical assistant translated for the provider. Most patients who received care at this

location, had a college education and were from a higher socioeconomic background. Patients

with a disability, had the same accommodations routinely provided.

FIVE WISHES 23

Subject Recruitment

Subject recruitment was via convenience sampling. All patients who met inclusion

criteria and were scheduled to see a provider during the study implementation period were

offered an opportunity to discuss ACP with their provider and given an invitational flyer on the

Five Wishes seminar (Appendix F). Participants in the Five Wishes workshop comprised of a

sampling from these patients, their family and friends. Electronic exam room posters

advertising the Five Wishes Seminar and were visible in all four examine rooms. The free

seminar took place on Thursday evenings from 5:00 to 6:30pm, each week, during the 12-week

study period. One seminar was cancelled due to AV equipment malfunctioning.

Consent Procedure

Consent to participate in the Five Wishes seminar was obtained in writing from the

patient by the nurse practitioner prior to each educational session (Appendix C). The patient

population seen for ACP engagement at the office location, did not require consent as assessing

interest in ACP is currently mandated by the 1991 PDSA and is a standard of care. In addition,

all patients have HIPPA protection of their personal health information (PHI). Discussions

about ACP in the office group was done privately between the provider and patient at the office

encounter in a closed, exam room. No PHI from either group was published. The paper

consents from the seminar were locked up in a secure cabinet inside the primary care practice

and will be destroyed in May 15, 2020.

Risks/Harms

There were minimal expected risks or harms associated with participation in ACP and the

Five Wishes seminars. Theoretically, a discussion about death could be emotionally upsetting

FIVE WISHES 24

for some patients. However, interest in discussing ACP with the patient’s provider was optional

and consistent with the standard of care. No patients were required to complete an AD nor

discuss ACP against their will.

Subject Costs/Compensation

A cost/benefit analysis is noted in Table 1. The cost of utilities, rent, and other

operational cost were minimal and already part of the practice’s current budget. The

implementation of this project required minimal, extra work from the current medical assistants

and the providers. Providers continued to be paid according to their contracts, which is based on

productivity, not hourly wages. The educational seminar took place in the office, after hours

when the office was traditionally vacant. No significant, extra cost was incurred from using the

building after hours. Although the seminar was led, voluntarily, by a nurse practitioner during

unpaid hours, for future consideration, the cost of a nurse led seminar has been included. Other

additional cost from this project were the start-up cost of materials. Revenue was generated

based on provider engagement and billing of the CPT code 99497 for Advance Care Planning.

No financial compensation to the subjects was provided for discussing ACP with their

provider. However, patients who participated in the Five Wishes seminar were given a free copy

of the AD known as Five Wishes. To purchase this AD as an individual, the patient would have

paid five dollars. The practice obtained copies of Five Wishes for $1 per copy. The cost of 120

copies of Five Wishes, along with a total 1,200 photocopies of the invitational flyer, and the cost

of the Five Wishes supplemental DVD, was close to the estimated cost of $240. Participation in

the seminar did not require completion of the Five Wishes AD but only one copy of Five Wishes

was given to each participant.

FIVE WISHES 25

Intervention

Before implementation, the three providers involved were given education on shared

decision-making skills. This education was presented at the practice meeting along with a one-

page summary on the Four Habits of Communication (Appendix D). Providers were asked if

they read the summary with all affirmative responses. At check in, every patient with an office

appointment was asked three kiosk enabled questions to determine their interest in ACP

(Appendix E) and given a paper flyer with information about the Five Wishes Seminar by the

secretary (Appendix F). The screening questions asked at each appointment were: if they have

an advance directive, if they know what an AD is and if they want to discuss an advance

directive at that visit. The responses to these questions were uploaded to the office note by the

medical assistant for the providers to see in the EHR. The process of an EHR notification acted

as a research supported reminder to providers and efficiently communicated the patient’s interest

in ACP. Even if the patient was interested in ACP, it was still up to the provider to start that

discussion. In addition, these questions served as a successful “ice breaker” to what is known to

be a difficult topic. If time constraints existed, the provider could suggest the patient return for a

separate office visit to specifically discus ACP or attend the Five Wishes Seminar. If the patient

was not interested, the provider could still decide to engage in an ACP discussion or simply

remind the patient about the Five Wishes Seminar. Providers documented an ACP discussion by

ICD-10 coding, and it was at their discretion to bill that the discussion qualified for a CPT billing

code.

The invitational flyer for the Five Wishes seminar was given to every patient (Appendix

F). The flyer provided information on location, date and time of the Five Wishes Seminar. The

flyer included a statement to encourage patients to bring a loved one to the seminar. At the

FIVE WISHES 26

seminar, consent was signed, and a pre-seminar questionnaire completed with Likert Scaled

response, before watching a short 30-minute video created by the makers of Five Wishes. After

the video, patients were encouraged to informally ask an acute care nurse practitioner questions

about end of life care or the Five Wishes AD. After the seminar was completed, the same

questionnaire was given again to the participants. This questionnaire was intended to

qualitatively assess a change in the perceived value of ACP after exposure to the educational

seminar (Appendix B). Completion of Five Wishes was not required, and this was stated at

every seminar.

Outcomes to be Measured

The outcomes measured in this project included provider engagement in ACP, percentage

of existing ADs and perceived value of the Five Wishes Seminar. The first outcome was

evaluated by the number of ACP discussion, documented by ICD-10 coding compared to the

number of ACP discussion at this same location, 12-weeks prior to project implementation. The

second outcome regarding existing ADs, was quantitatively assessed and documented by the

medical assistant in a consistent location within the EHR. This was double checked during data

retrieval and then reported as a percentage of patient encounters. Demographic information

about the patient population during the study period was also evaluated and included, age,

gender, marital status, employment status, ethnicity and race. Given the control was the same

population of patients, it was assumed to be the same cohort. A chart audit of participation in

ACP, was assessed before and after the study via ICD-10 and CPT billing claims.

The third outcome measured patients’ perceived value of the nurse practitioner led

educational session on the specific AD known as Five Wishes. This outcome was evaluated

FIVE WISHES 27

through the mean questionnaire responses pre and post Five Wishes seminar with the mean

Likert scores analyzed for statistical reliability via a paired t-test (Appendix B).

Project Timeline

The project timeline first started with an assessment of the need for this project in the

practice and the owners’ interest in supporting an ACP project. A table of the timeline is noted

in Figure 3. Once the evidence-based research had been reviewed, a project was developed, and

SWOT concerns addressed to improve participation and success. Development continued with a

review of the literature and assessment of cost versus benefit. After reviewing the evidence-

based research, a plan was developed that includes the evidence that supports successful

ACP. The SWOT concerns were addressed by engaging “buy in” from ancillary staff and the

providers. Unfortunately, many of the threats and weaknesses could not be addressed, such as

cultural perceptions about end of life care and office geography.

Next, the project was implemented using PET to guide design. The 12- week project

started on September 2

nd

and end November 22, 2019. The Five Wishes seminars started the

first Thursday after implementation. One planned seminar was cancelled due to equipment

malfunction. Evaluation began after the project had been implemented with the data evaluated

after completion and compared to the 12-weeks before implementation. Seminar attendance and

questionnaires responses were placed into an Excel spreadsheet for easier manipulation with

SPSS (Appendix G).

Resources Needed

Resources needed for this project were paper copies of the questionnaires and color

copies of the invitational flyer. The AD Five Wishes cost $1.00 per copy and a copy of the

FIVE WISHES 28

educational Five Wishes DVD was purchased for $24.95 plus tax. The practice purchased 100

copies of Five Wishes in English and 10 copies each of Five Wishes in Spanish and

Russian. The current AV equipment owned by the practice was used to view the Five Wishes

DVD. Other resources needed included the office space after hours for the educational seminars

as well as SPSS software, an EHR and electronic tablet as well as resource staff such as: medical

assistants, IT staff, providers, and the office secretary. Parking at the office is free.

Results

A total of 1037 office encounters were used to assess provider engagement in ACP

discussions. Some patients were seen multiple times during the 12-week period. Although the

repeated patients were given the same questions at each visit, their responses were not always the

same. Most patients who were seen during the study period had commercial insurance, were

employed full time, married, white and non-Hispanic. Table 3 gives more specific data

regarding the demographics of the population studied. The median age of participants was 53.

The minimum age was 18 and the oldest participant was 97. Histogram confirmed an equitable

distribution among all age groups and division between men and women was 39 % and 61%,

respectively. The percentage of Medicare patients who participated was 20%. Unfortunately,

220 office encounters were excluded from data analysis due to missing responses to the three

pre-visit questions or lack of questions being uploaded into the EHR correctly. Patients who had

at least one response to the three questions uploaded into the EHR were included in the data

analysis.

Provider engagement was evaluated by Chi Square analysis and cross tabulated to the

patient response to the “check in” question regarding interest in discussing ACP . The data

results were statistically significant with a X2=205.561 and p<0.001. Cronbach’s Alpha

FIVE WISHES 29

reliability for these questions was 0.512. A total of six patients had engaged in ACP discussions

at this office location, by these same providers in the 12-weeks before implementation. At the

end of the 12-week implementation period, a total of 90 patients participated in an ACP

discussion with their provider.

The second aim was to document patients who had an existing AD. This was assessed as

a descriptive result. Prior to this intervention, there was not a consistent process in place to

record that patients had an existing AD. This QI project allowed for a consistent opportunity to

ask patients if they had an AD and document their response. The results over 12-weeks of

patient encounters showed that of the 1037 patient encounters, 237 (22.9%) of the encounters

answered the question that they had an existing AD. This number is slightly lower than other

reported percentage that estimate approximately 33% of American adults have an AD (Yakov

et.al, 2017). Given the denominator of this data evaluation was based on the number of

encounters and not individual patients, the percentage of existing ADs may be higher than 23%.

The third aim was to create a valuable, educational seminar on a specific AD known as

Five Wishes. A total of 22 people attended the seminars during the 12-week implementation

phase. One person arrived after the video started and thus was not included in the statistical

analysis. No demographic information for the Five Wishes participants was collected other than

gender. The cohort of participants included 14 females and 7 males. On one occasions, the

seminar was cancelled due to equipment malfunction. All participants were given a pre and post

questionnaire regarding their opinion about Five Wishes and ADs, in general. The same

questionnaire was given pre and post seminar with Likert scaled responses (0-5) that numerically

correlated with positive opinions about ADs. These responses were averaged and the mean

FIVE WISHES 30

responses analyzed via a paired t-test analysis comparing pre and post questionnaire responses.

Cronbach’s Alpha for this questionnaire was 0.771.

The 21 responses analyzed showed mixed statistically significance. The response to

questions 3, 4 and 6 for the pre and post Five Wishes questionnaire did have statistically

relevance with a p<0.05 (Table 3). However, mean scores for both the pre and post

questionnaire responses were positive and averaged over 4. The first question was not analyzed

because it was a statement about an existing AD and thus post questionnaire responses were

unchanged. Question 4 stated “I think Five Wishes is an advance directive I will use” and pre

and post p value for this response was <0.05. The pre mean score for this question was 3.43 and

post mean score was 4.62 suggesting the seminar was successful in meeting the objective of

educating patients on the value of Five Wishes as an AD. The questionnaire responses, albeit

positive, lacked variability as most of the participants already had a favorable opinion of AD,

indicating a ceiling effect. In addition, the providers subjectively felt the ACP seminar was an

added value to the practice. Given most of the patients seen during implementation, work full

time, this seminar may have been more successful if held on a weekend instead of mid-week at

5pm.

In the end, there was a significant improvement in ACP discussions with the EHR

reminders of patient’s interest in ACP. In total, 116 patients answered that they wanted to

discuss ACP at that visit, yet only 51 (44%) of those who answered yes, had a provider engage in

an ACP discussions. Surprisingly, 39 (4%) patients who had answered “no” to their interest in

discussing ACP, still had a provider engaged in an ACP discussion. This suggest that patients

are 10 times more likely to have an ACP discussion if simply asked about interest in ACP. The

elicited interest and visual reminder of the responses in the EHR did motivate provider

FIVE WISHES 31

engagement. Most patient encounters (87.3%) answered that they did not want to discuss ACP

however, 56% of these patients who did not want to discuss ACP also did not know what an AD

was. This creates an opportunity for future ACP research to work on better methods to educate

the general population about ADs and normalize discussions about ACP in primary care.

The other value of this study design is the benefit of eliciting interest about the topic of

end of life care with a non-threatening process. Patients who wanted to discuss ACP had the

ability to confirm their interest by a simple intake response which gave the provider an “ice

breaker” to start the difficult conversation about dying and end of life care. It also allowed

complete inclusion of everyone in this opportunity, not just aging and medically ill. Lastly, just

by asking the questions, the topic and terminology was introduced to patients who may otherwise

never hear these terms. Primary care is the obvious place for ACP discussions to originate given

the close relationships garnered in this setting. We must continue to find creative ways to

engage patients in this important but challenging topic.

Discussion

The implications to clinical practice are to change when ACP is discussed in primary

care. This project demonstrated an easy and financially sustainable process utilizing technology

that is already in place. Making the terminology and opportunity to discuss ACP available at

every primary care encounter, changes the paradigm of who we assume needs this discussion but

most importantly, normalizes ACP. Waiting to address ACP when someone is medically ill or

faced with a terminal diagnosis is too late. This project successfully demonstrated how ACP can

easily be incorporated as a routine part of the primary care experience. End of life care will

always be a difficult topic to discuss but offering the information to everyone, can normalizes the

discussion and improve AD implementation.

FIVE WISHES 32

The healthcare policy most needed to continue to support ACP, is to continue to

incentivize provider engagement and patient participation in ACP. For example, many Medicare

recipients do not realize that they can make an appointment with their primary care provider just

to discuss ACP. Although this is already incentivized for the provider, it could also be

incentivized for the patient. Annual wellness visits include numerous questions about safety,

socioeconomic, existing AD and care needs. However, in clinical practice, the AD component

of this questionnaire gets buried by the other areas of concern, like falls and referrals to

specialist. A specific, patient incentive to see a provider just for ACP, either through a monetary

or access reward, could help perpetuate this discussion.

Implications for executive leadership are to financially support clinical processes that

facilitates this paradigm shift of asking every adult about ACP at every office location. In

addition, with better documentation of existing AD, a process to communicate this existing

document with specialist and hospitals needs to be implemented. Knowing patients have an AD

is only the first step in using ADs. Because research also supports the value of a team-based

approaches to ACP, leadership could facilitate ACP through advertising that patients can make

appointments just to discuss ACP and continue free ACP seminars facilitated by other specialist

such as spiritual leaders, social workers, attorneys, etc. The normalization of ACP is supported

by making ACP a separate “product line” advertised and supported with a variety of resources.

Implications for quality and safety are in utilizing healthcare resources responsibly and

improve our ability to meet the standards of care. This primary care practice is part of an

Accountable Care Organization where the quality of care impacts reimbursement and ACP is a

quality measure that impacts outcomes. ACP address quality in an ACO through reduction in

FIVE WISHES 33

unnecessary healthcare spending without impacting care quality. The healthcare community has

a responsibility to demonstrate quality while being good stewards of healthcare resources.

Sustainability and Future Scholarship

There was strong, financial sustainability demonstrated by this project. Approximately

$4000 in revenue was generated by this process. The process of utilizing the current electronic

health resources created a seamless process to continue to normalize the terminology of ACP and

engage more patients in an ACP discussion. Medicare reimbursement as well as some

commercial insurance reimbursement of ACP engagement allows this project to continue to be

sustainable. Future scholarship should focus on creative ways to educate and engage more

patients in understanding the value of AD and ACP. This project demonstrated that most people

did not want to discuss ACP, but normalization of these discussion, could change this pervasive

opinion. Normalization can only be achieved by continuing research that address ACP in

primary care.

Conclusion

In summary, an ACP process is a valuable addition to any primary care practice and

especially for a primary care practice that values comprehensive care. This project added a

missing aspect to the goal of holistic care. Evidence-based research on ACP was translated into

a successful clinical process that has benefits beyond cost and most importantly, advances the

conversation about end of life care. Ultimately, a successful ACP process can normalize how

we discuss death with patients and open opportunities to better understand the value of an AD,

especially the unique AD known as, Five Wishes.

FIVE WISHES 34

Figure 1 Revised Johns Hopkins Model (Revised Johns Hopkins Model, n.d)

FIVE WISHES 35

Figure 2 Methodology Map

FIVE WISHES 36

Figure 3 Project Timeline

Nov/Dec 2018:

Owner

interest/Needs

Assessment

March-June

2019 SWAT

Analysis/EBR

assessed

June-August

2019: Staff "buy

in", Process

created, resources

obtained

September 2019-

December 2019:

Implementation of

project

January-May

2020: data

analysis and

evaluatation of

implementation

process for

practice wide use

FIVE WISHES 37

References:

Advance Directives. (n.d.). Retrieved from

http://www.marylandattorneygeneral.gov/Pages/HealthPolicy/AdvanceDirectives.aspx

Aging with Dignity. (2012, July 12). Retrieved February 16, 2019, from

https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/1997/01/aging-with-dignity.html.

Baik, D., Cho, H., & Creber, R. M. (2018). Examining Interventions Designed to Support Shared

Decision Making and Subsequent Patient Outcomes in Palliative Care: A Systematic

Review of the Literature. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative

Medicine®,36(1), 76-88. doi:10.1177/1049909118783688

Bond, W. F., Kim, M., Franciskovich, C. M., Weinberg, J. E., Svendsen, J. D., Fehr, L. S., . . .

Asche, C. V. (2018). Advance Care Planning in an Accountable Care Organization Is

Associated with Increased Advanced Directive Documentation and

Decreased Costs. Journal of Palliative Medicine,21(4), 489-502.

doi:10.1089/jpm.2017.0566

Dearholt, S. & Dang, D (2018). Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-Based Practice Model and

Guidelines. Indianapolis, IN: Sigma Theta Tau International.

Douglas, R., & Brown, H. N. (2002). Patients Attitudes Toward Advance Directives. Journal

of Nursing Scholarship,34(1), 61-65. doi:10.1111/j.1547-5069.2002.00061.x

E-Clinical Works (ECW) [Program documentation]. (n.d.). Retrieved April 1, 2019.

Forcino, R., Paul, B. J., James, O., Roger, A., & Molly, C. (2018). Using CollaboRATE, a brief

patient-reported measure of shared decision making: Results from the three clinical

FIVE WISHES 38

settings in the United States. Health Expectations,21, 82-89.

doi:10.1111/hex.12588

Hayek, S., Nieva, R., Corrigan, F., Zhou, A., Mudaliar, U., Mays, D., . . . Ilksoy, N. (2014). End-

of-Life Care Planning: Improving Documentation of Advance Directives in the

Outpatient Clinic Using Electronic Medical Records. Journal of Palliative Medicine,

17(12), 1348-1352. doi:10.1089/jpm.2013.0684

Hilgeman, M. M., Uphold, C. R., Collins, A. N., Davis, L. L., Olsen, D. P., Burgio, K. L., . . .

Allen, R. S. (2018). Enabling Advance Directive Completion: Feasibility of a New

Nurse-Supported Advance Care Planning Intervention. Journal of Gerontological

Nursing, 44(7), 31-42. doi:10.3928/00989134-20180614-06

Hinderer, K. A., & Lee, M. C. (2014). Assessing a Nurse-Led Advance Directive and Advance

Care Planning Seminar. Applied Nursing Research,27(1), 84-86.

doi:10.1016/j.apnr.2013.10.004

Jensen, B. F., Gulbrandsen, P., Dahl, F. A., Krupat, E., Frankel, R. M., & Finset, A. (2011).

Effectiveness of a short course in clinical communication skills for hospital doctors:

Results of a crossover randomized controlled trial (ISRCTN22153332). Patient

Education and Counseling, 84(2), 163-169. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2010.08.028

Life in USA. Death in USA. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.lifeintheusa.com/death/

Maryland Attorney General. (n.d.). Retrieved from

http://www.marylandattorneygeneral.gov/Pages/HealthPolicy/AdvanceDirectives.aspx

FIVE WISHES 39

Pelland, K., Morphis, B., Harris, D., & Gardner, R. (2019). Assessment of First-Year Use of

Medicare’s Advance Care Planning Billing Codes. JAMA Internal Medicine.

doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.8107

Raghavan, D. (2014, July 03). Most Educated Places in America. Retrieved April 13, 2019, from

https://www.nerdwallet.com/blog/mortgages/home-search/educated-places-

america/?trk_location=ssrp&trk_query=most educated city in

US&trk_page=1&trk_position=1

Rao, J. K., Anderson, L., Lin, F. C., & Laux, J. (2014). Information for CME Credit —

Completion of Advance Directives Among U.S. Consumers. American Journal of

Preventive Medicine, 46(1). doi:10.1016/s0749-3797(13)00608-9.

Reinhardt, J. P., Chichin, E., Posner, L., & Kassabian, S. (2014). Vital Conversations with

Family in the Nursing Home: Preparation for End-Stage Dementia Care. Journal of

Social Work in End-Of-Life & Palliative Care, 10(2), 112-126.

doi:10.1080/15524256.2014.906371

Revised Johns Hopkins Model [Digital image]. (n.d.). Retrieved from

https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/evidence-based-practice/ijhn_2017_ebp.html

Ruparel, M., Quaife, S. L., Ghimire, B., Dickson, J. L., Bhowmik, A., Navani, N., . . . Janes, S.

M. (2019). Impact of a Lung Cancer Screening Information Film on Informed Decision-

making: A Randomized Trial. Annals of the American Thoracic Society, 16(6), 744-751.

doi:10.1513/annalsats.201811-841oc

FIVE WISHES 40

Splendore, E., & Grant, C. (2017). A nurse practitioner–led community workshop. Journal of the

American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 29(9), 535-542. doi:10.1002/2327

-6924.12467

Tripken, J. L., Elrod, C., & Bills, S. (2016). Factors Influencing Advance Care Planning Among

Older Adults in Two Socioeconomically Diverse Living Communities. American

Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine®,35(1), 69-74.

doi:10.1177/1049909116679140

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.) Retrieved from

https://health.gov/communication/literacy/issuebrief/

Van Wert (2018, August 19). Four key components of a successful advance care planning

program. Retrieved April 27, 2019 from https://vyncahealth.com/four-keu-components

-successful-advance-care-planning-program/

Verhovshek, J. (2016). The Medicare Advance Care Planning Benefit. Retrieved from

https://www.aapc.com/blog/34941-the-medicare-advance-care-planning-benefit/

Whelan, D. (2013, June 19). ObamaCare Dives Into End-Of-Life Debate. Retrieved April 11,

2019, from https://www.forbes.com/2009/07/24/obamacare-medicare-death-business-

healthcare-obamacare.html#15bc567d4ef6

FIVE WISHES 41

Appendices

Appendix A Evidence Table

Article Author Evidence Sample Findings Observable Limitations Evidence

Level/Quality

Arti

cle

Author

Evidence

Type

Sample,

Sample

Size,

Setting

Findings that

help answer

the EBP

Question

Observable

Measures

Limitations

Evide

nce

Level

&

Qualit

y

Arti

cle

#1

Hayek,

et. al.

(2013)

Prospecti

ve QI

study

588 patient

charts were

screened

with 157

meeting

criteria for

AD

documenta

tion

The study

implemented

an EHR based

reminder for

patients with

eligible

chronic

medical

conditions. An

EHR based

reminder does

improve

providers

documentation

of AD and

ACP. The

study used the

EHR to

implement a

reminder

process and

likely, a

similar

reminder will

be needed for

my project.

An EHR based

reminder for

providers to

address

ACP/ADs did

improve

documentation

of ADs.

However, more

than one

reminder

correlates with

better

implementation.

The authors

also suggest

that a dedicated

location to

documente AD

improved

documentation.

These are all

factors that will

need to be part

of my project to

address

provider

engagement in

ACP. Provider

engagement is

one of my

SWOT

concerns.

Primary care

providers were

given

reminders to

address

AD/ACP for

only patients

who met

criteria for

chronic

medical

problems

however, all

patients were

encouraged to

complete an

ACP. People

with end of life

and serious

medical

problems may

be more likely

to complete

ADs and thus

may explain

the significant

participation.

The sample

size was small.

Interestingly,

the ACP

conversations

were via

medicine

IIA

FIVE WISHES 42

residents in

training rather

than by

primary care

providers with

long standing

relationships.

This may be a

function of

excellent

patient

centered

communication

. Regardless,

there is clear

support to

having

electronic

reminders for

my AD/ACP

project.

Arti

cle #

2

Hinder

er, K.,

et, al.

(2014)

Quasi-

Experim

ental

86

voluntary

participant

s from the

community

age 20-89

Community

participants

were offered

free,

informational

sessions about

Five

Wishes. This

study mirrors

my project by

evaluating a

nurse lead

informational

session on

Five Wishes

AD

planning. Find

ings did not

correlate with

a change in

ADAS scores

(patients’

attitude) about

ACP post

educational

seminar. How

ever, most

found the

seminar useful.

Advance

Directive

Attitude Survey

(ADAS) score

ranged from 16-

54 with a higher

score

correlating with

more favorable

attitudes

towards

ACP. The

study found no

change in

ADAS scores

pre, post and 1

month after

educational

session.

However, after

the session,

97.7% reported

they were likely

to complete an

AD. The lack

of change in

ADAS score

may be related

to 40.7% had

ADAS scores

were measured

prior,

immediately

post and 1

month after

educational

intervention.

No data on

implementatio

n of AD one

month after the

session was

measured. Bec

ause this took

place in a

community

setting rather

than in

conjunction

with a primary

care practice,

patients who

already

understood and

valued ACP,

may have

disproportionat

ely represented

IIB

FIVE WISHES 43

This supports

my plan to

incorporate

AD (Five

Wishes)

informational

sessions after

office hours

and open to

patients and

loved ones to

attend as an

intervention to

improve

understanding

and give more

opportunities

to answer

questions

about ACP.

been a surrogate

decision makers

and already had

a positive

attitude, 30%

already had an

AD and nearly

69% had

already

discussed ACP

with a

provider. Despi

te this,

participant post

intervention

survey found

the majority

82.6% did find

the seminar

useful. This

supports the

need for

informational

sessions in my

project but in

conjunction

with SDM and

provider

support. The

study also

included a

demographic

instrument

created

specifically for

the study and

likely will also

be needed in

my project.

Because the

ADAS tool is

valid and

reliable, it will

be used to

measure

attitudes about

ACP in my own

5 Wishes

informational

session.

the sample of

participants.

Assessing a

larger cohort of

primary care

patients’

understanding

of ACP before

and after could

be valuable to

see if this type

of

informational

session

improves

primary care

patients’

attitudes, and

knowledge of

ACP and AD

implementatio

n.

FIVE WISHES 44

Arti

cle

#3

Tripke

n, J.L,

et. al.

(2018).

Qualitati

ve Cross-

sectional

survey

77 adults

55 years

and older

were

surveyed

from two

different

socioecono

mic living

communiti

es

Adults living

in High

Income

Eligible (HIE)

were more

likely to

engage in ACP

compared to

people in an

Affordable

Housing

Communities

(AHC)

Because ACP is

such a complex

process, this

article

highlights that

socioeconomic

status does

impact

ACP. This

encourages the

need for my

project to target

at risk groups

who may be

less informed

about ACP.

Given we know

ACP

substantially

impacts end of

life care, this

socioeconomic

group needs

additional

focused

outreach to

reinforce the

value of ACP.

Education

levels differed

significantly

among the two

groups and

correlated with

socioeconomic

status. I

suspect

exposure to

information

about ACP is

more likely to

have occurred

with people in

a higher

socioeconomic

and

educational

level. For

example, many

people fill out

an advance

directive when

they write their

living will.

Less educated

people may be

less likely to

have a living

will and miss

the opportunity

to learn about

AD. Interestin

gly, the study

evaluated self-

reported health

status of each

group. The

group least

likely to

complete an

ACP were also

the group that

reported the

poorest health

status. This

highlights that

ACP may be a

function of

repeated

IIIA

FIVE WISHES 45

exposure to the

information

and providers

may be

unintentionally

avoiding ACP

to this subset

population. If

you have

poorer health,

you

theoretically

would have

more contact

with a provider

and thus more

opportunities

to discuss

ACP.

Therefore, I

am opening my

project to

everyone.

With repeated

exposure to the

information

comes equal

opportunity for

everyone to

create an AD.

Lastly, despite

these

differences in

ACP

knowledge,

both groups

had similar

attitudes and

desires

regarding

death and

dying.

Arti

cle #

4

Splend

ore, E.

et. al,

(2016)

Quasi-

experime

ntal

Convivenc

e sample of

40 (23

from the 1

st

workshop

and 17

from the

second)

Study

concluded that

a Five Wishes

educational

workshops in a

community

setting

increased

Pre-workshop

questionnaires

with 19 self-

reported and

open-ended

questions on

understanding,

perception of

There was not

a standardized

questionnaire

nor was the

completion of

AD

verified. Verif

ication of an

IIB

FIVE WISHES 46

participant

s over the

age of 18

from a

rural town

in

Pennsylvan

ia attended

an ACP

workshop

held

twice. No

statistical

difference

in the two

groups that

attended

the

workshops.

understanding,

completion

and discussion

of ACP/AD

among

participants

and their

family

members. This

AD workshop

on discussing

Five Wishes is

part of my

DNP project

and thus the

implementatio

n method of

this study is

valuable.

importance and

dissemination

of ACP status

was measured

via Likert type-

1

questions. Post

workshop

evaluations

were also self-

reported

questionnaires

and then a 1

month follow

up phone call

questionnaire

with 8 self-

reported

answers

regarding the

ACP process,

implementation

and perception

of importance

was

completed.

AD for my

project is

important as

many studies

show patients

agree with the

value of ACP,

but fewer make

the step to

complete an

AD and thus

AD

documented

completion

will be a

measured

value for my

project. Prima

ry care

providers were

not part of this

ACP process in

this study as it

was a

community

project. In

addition, the

study was

supported by

Aging with

Dignity who

developed the

Five Wishes

tool creating

some potential

bias.

Arti

cle #

5

Forcin

o, R.

et. al.

(2017)

Quasi-

experime

ntal

Survey

3 separate

primary

care

practice

sites in the

US asked

patients

over 18,

post visit,

the

CollaboRA

TE patient

survey tool

to measure

The study was

intended to

evaluate

CollaboRATE

scores for 3

outpatient

primary care

practice in 3

different

geographical

locations to

assess in real

time, a

patient’s

Results

conclude that

CollabRATE

can be used in a

diversity of

primary care

settings and the

short

measurements

tools reduce

some of the

administrative

burden of

collecting

Validity and

reliability of

the

CollaboRATE

tool is noted in

a “simulation

sample”. This

study has value

in its ability to

assess shared

decision