World

Population

Policies related to fertility

2021

Policies

UN DESA/POP/2021/TR/NO. 1

Department of Economic and Social Affairs

Population Division

World Population Policies 2021

Policies related to fertility

asdf

United Nations

New York, 2021

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Aairs, Population Division

e Department of Economic and Social Aairs of the United Nations Secretariat is a vital interface between

global policies in the economic, social and environmental spheres and national action. e Department

works in three main interlinked areas: (i) it compiles, generates and analyses a wide range of economic,

social and environmental data and information on which States Members of the United Nations draw to

review common problems and take stock of policy options; (ii) it facilitates the negotiations of Member

States in many intergovernmental bodies on joint courses of action to address ongoing or emerging

global challenges; and (iii) it advises interested Governments on the ways and means of translating policy

frameworks developed in United Nations conferences and summits into programmes at the country level

and, through technical assistance, helps build national capacities.

e Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Aairs provides the international

community with timely and accessible population data and analysis of population trends and development

outcomes for all countries and areas of the world. To this end, the Division undertakes regular studies of

population size and characteristics and of all three components of population change (fertility, mortality

and migration). Founded in 1946, the Population Division provides substantive support on population and

development issues to the United Nations General Assembly, the Economic and Social Council and the

Commission on Population and Development. e Population Division also leads or participates in various

interagency coordination mechanisms of the United Nations system. It also contributes to strengthening the

capacity of Member States to monitor population trends and to address current and emerging population

issues.

Suggested citation

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Aairs, Population Division (2021). World Population

Policies 2021: Policies related to fertility. UN DESA/POP/2021/TR/NO. 1.

is report is available in electronic format on the Division’s website at www.unpopulation.org. For further

information about this report, please contact the Oce of the Director, Population Division, Department of

Economic and Social Aairs, United Nations, New York, 10017, USA, by Fax: 1 212 963 2147 or by email at

popula[email protected]g.

Copyright information

Front cover: Murje Netu and her son aer seeking services at the Wamba Local Government Primary

Health Care Centre in Wamba, Nigeria, by Dominic Chavez/e Global Financing Facility, 2018.

Back cover: Adolescent health in Mozambique, by the Global Financing Facility, 2019.

United Nations Publication

Sales No.: E.22.XIII.1

ISBN: 9789211483635

eISBN: 9789210000949

Copyright © United Nations, 2021.

Figures and tables in this publication can be reproduced without prior permission, made available under a

Creative Commons license (CC BY 3.0 IGO), http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo/

Acknowledgements

is report was prepared by Guangyu Zhang, Stephen Kisambira and Karoline Schmid. e authors wish to

thank John Wilmoth, Jorge Bravo, Vinod Mishra and Bela Hovy for their input in reviewing the dra.

e assistance of Donna Culpepper and Neena Koshy in editing and desktop publishing is acknowledged.

Contents

Executive summary .......................................................................................................1

Introduction ......................................................................................................................3

Government fertility and family planning policies through 2019 ..............5

Government policies and related responses: Case studies ......................... 13

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on fertility ........................................ 27

Summary and policy considerations ..................................................................... 31

References ....................................................................................................................... 32

Annex table .................................................................................................................... 36

Notes on regions, development groups, countries and areas

e designations employed in this publication and the material presented in it do not imply the expression

of any opinions whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status

of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or

boundaries. e term “country” as used in this report also refers, as appropriate, to territories or areas.

In this publication, data for countries and areas are oen aggregated in six continental regions: Africa,

Asia, Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean, Northern America, and Oceania. Further information on

continental regions is available from https://unstats.un.org/unsd/methodology/m49/. Countries and areas

have also been grouped into geographic regions based on the classication being used to track progress

towards the Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations (see https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/

indicators/regional-groups/).

e designation of “more developed” and “less developed”, or “developed” and “developing”, is intended for

statistical purposes and does not express a judgment about the stage in the development process reached

by a particular country or area. More developed regions comprise all countries and areas of Europe and

Northern America, plus Australia, New Zealand and Japan. Less developed regions comprise all countries

and areas of Africa, Asia (excluding Japan), Latin America and the Caribbean, and Oceania (excluding

Australia and New Zealand).

e group of least developed countries (LDCs) includes 47 countries, located in sub-Saharan Africa (32),

Northern Africa and Western Asia (2), Central and Southern Asia (4), Eastern and South-Eastern Asia (4),

Latin America and the Caribbean (1), and Oceania (4). Further information is available at http://unohrlls.

org/about-ldcs/.

e group of Landlocked Developing Countries (LLDCs) includes 32 countries or territories, located in

sub-Saharan Africa (16), Northern Africa and Western Asia (2), Central and Southern Asia (8), Eastern

and South-Eastern Asia (2), Latin America and the Caribbean (2), and Europe and Northern America (2).

Further information is available at http://unohrlls.org/about-lldcs/.

e group of Small Island Developing States (SIDS) includes 58 countries or territories, located in the

Caribbean (29), the Pacic (20), and the Atlantic, Indian Ocean, Mediterranean and South China Sea

(AIMS) (9). Further information is available at http://unohrlls.org/about-sids/.

e classication of countries and areas by income level is based on gross national income (GNI) per capita

as reported by the World Bank (June 2018). ese income groups are not available for all countries and areas.

Further information is available at https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase /articles/906519-

world-bank-country-and-lending-groups.

World Population Policies 2021: Policies related to fertility

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Aairs, Population Division

1

Executive summary

e report provides a brief overview of global fertility levels and trends since the early 1960s and explores

government’s views and policies related to fertility. e analysis of views and policies draws on data gathered

through 2019 and available in the World Population Policies Database (box 1), reecting the situation before

the outbreak of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. e report then presents ve case

studies of countries from dierent regions and with a range of fertility levels, exploring in more detail the

origin and evolution of national fertility policies. e case studies are followed by an assessment of known

or potential direct and indirect impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on fertility patterns and trends. e

report concludes with an exploration of policy options that governments may wish to consider in the current

context.

Below are some key conclusions of the report:

• Globally, through 2019, nearly three quarters of governments had policies related to fertility. Of these,

69 governments had policies to lower fertility, 55 aimed to raise fertility, and 19 focused on maintaining

current levels of fertility. A total of 54 governments did not have an ocial fertility policy.

• e data suggest an association between the kinds of policies in place between 2015 and 2019 and

fertility levels observed in that period. Among the 69 countries with policies to lower fertility, 10 were

high-fertility countries in 2019, and 50 had intermediate fertility levels. Of the 55 countries with policies

to raise fertility, 40 had low levels of fertility in 2019, including 18 with very low levels.

1

• In developed countries with older populations, governments were more likely to have policies intended

to raise fertility. Among developing countries, nearly half had policies to lower fertility, while one quarter

did not have an ocial policy related to fertility. Among the least developed countries (LDCs), whose

combined population continues to grow rapidly, an increasing number of governments had policies

seeking to lower fertility.

• Fertility policies show considerable variation across regions. In sub-Saharan Africa and Oceania

(excluding Australia and New Zealand), governments were more likely to have policies to lower fertility,

whereas in Europe and Northern America and in Eastern and South-Eastern Asia, policies to raise

fertility were more prevalent. In Latin America and the Caribbean, around half of the countries had no

specic policy designed to inuence fertility levels.

• An overwhelming majority of governments (over 95 per cent, or 98 of 103 countries with available

data in 2019) provided family planning services to their populations, either directly through public

programmes or indirectly through non-governmental organizations. Direct support was provided by 80

governments, of which 68 reported supporting family planning both directly and indirectly. In addition,

18 governments provided only indirect support.

• For a large majority of the 11 countries with high levels of fertility and available data on policies in 2019,

governments had adopted one or more policy measures aimed at (a) raising the age of marriage or union

formation, (b) raising the age of the mother at the time of her rst birth, or (c) increasing the duration of

time between successive births. Of the 52 countries with intermediate fertility levels and available data

on policies, about half aimed to raise both the age of marriage or union formation and the age of the

mother at the time of her rst birth. Although nearly half of the governments in these two groups (45)

aimed to increase the time between successive births, only 31 did this in combination with the other

two measures.

1

In this report, “high fertility” refers to a level of total lifetime fertility of at least 5.0 births per woman; “intermediate fertility”, between 2.1 and

5.0 births; and “low fertility”, below 2.1 births. “Very low fertility”, a sub-category of “low fertility”, refers to a level below 1.5 births per woman, and

“moderately low fertility”, another sub-category of “low fertility”, refers to a fertility level between 1.5 and 2.1 births per woman.

World Population Policies 2021: Policies related to fertility

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Aairs, Population Division

2

• Among the 81 countries with low fertility and available data on policies during 2015-2019, one measure

adopted by almost all governments was paid or unpaid maternity leave with job security. Beyond that,

the four most commonly adopted measures were (a) publicly subsidized childcare (88 per cent), (b) child

or family allowances (78 per cent), (c) paid or unpaid parental leave (73 per cent) and (d) paid or unpaid

paternity leave with job security (73 per cent). In addition, over half of these governments provided other

incentives, such as exible or part-time work hours for parents or tax credits for dependent children.

• Among the 102 countries with available data in 2019, 88 governments considered the fertility of

adolescents to be a matter of concern. is was true for almost all of the countries in sub-Saharan Africa

or in Latin America and the Caribbean that had adolescent fertility rates higher than 50 births per

1,000 women aged 15-19 years. Regardless of their specic views on adolescent fertility, the majority

of governments adopted measures to improve the sexual and reproductive health of adolescents by

providing school-based sexuality education and by raising rates of secondary school enrolment and

retention among girls and young women.

• e country case studies illustrate the link between fertility policies adopted by governments and

the fertility patterns and trends prevailing in their countries. Kenya, which had high levels of fertility

as recently as 2000-2005, became the rst country in sub-Saharan Africa to adopt a national family

planning programme in 1967, contributing to a reduction in the country’s fertility level from 8.1 births

per woman in 1965-1970 to 3.5 in 2015-2020. In Argentina, a country where low levels of total lifetime

fertility have been accompanied by high levels of adolescent fertility, government policies have focused

specically on lowering the adolescent birth rate.

• In Hungary, the Government has expressed concern about persistent low levels of fertility and has

adopted a range of policies that explicitly encourage childbirth. By contrast, Australia does not have

an ocial policy to raise the fertility level but has adopted a range of family policies that support

childbearing and childrearing. China, aer implementing a strict one-child policy for three decades,

has in recent years changed course in response to persistent low fertility and rapid population ageing; it

now allows all couples to have three children.

• e ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and resulting economic and social changes have aected fertility

levels in many countries, but this impact may be short-lived. Based on both historical experience and

available evidence about recent changes, it is expected that fertility uctuations from 2021 to 2023 will

be relatively minor and that fertility may return to pre-pandemic levels by around 2025. e COVID-19

pandemic is not expected to have a signicant impact on fertility patterns and trends in the long run.

World Population Policies 2021: Policies related to fertility

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Aairs, Population Division

3

Introduction

National population policies and family planning programmes have a long history. Policies that aimed to

lower fertility and curb population growth were a response to the rapid growth in populations, particularly

in Asia, that became apparent aer data became available from population censuses conducted in the early

1950s and later. Population experts and national and international leaders began calling for action to stem

rapid population growth (May, 2012). Two academic conferences on population, organized or co-organized

by the United Nations, were held in Rome in 1954 and Belgrade in 1965. Attended mostly by technical

experts, including from less developed countries,

2

these meetings focused on the relationship between

population growth and economic and social development, particularly in less developed countries, and on

policies and programmes to lower fertility and slow population growth.

e World Population Conference, held in Bucharest in 1974, was the rst of three intergovernmental

conferences on population convened by the United Nations. It attracted a broader audience than the earlier

academic conferences, including government ocials from 135 countries, and led to the adoption of the

World Population Plan of Action. Two years aer the Bucharest meeting, the governments of 40 countries,

including the most populous developing countries, initiated family planning policies with the aim of

slowing population growth. By 2013, this number had risen to 160 (de Silva and Tenreyro, 2017). During the

International Conference on Population, convened in Mexico City in 1984, and the International Conference

on Population and Development, held in Cairo in 1994, governments continued to work towards building a

global consensus around an approach to population policies that de-emphasized the pursuit of demographic

targets in favour of promoting women’s empowerment and improving maternal and child health, with an

emphasis on the provision of sexual and reproductive health care, including for voluntary family planning

(May, 2012).

In 1952, India became the rst country to adopt an ocial population policy, committing the country to

reduce substantially its level of fertility and establishing a national family planning programme. Other

countries and areas of Asia, including Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Singapore, Taiwan Province of China and the

Republic of Korea, followed suit.

Some population policies, especially in past decades, included specic quantitative targets and were not

entirely voluntary, sometimes using strong incentives or coercion to ensure widespread adoption of family

planning practices and leading in the most extreme cases to the use of forced sterilization or abortion as

means of population control.

3

However, most national population policies were not coercive and focused

instead on promoting a desire for smaller families with fewer, healthier and better educated children.

Especially since the Cairo conference in 1994, it has been increasingly recognized that population objectives

can be reached faster by giving priority to the needs of couples and individuals instead of focusing on

demographic or numerical targets.

With declining fertility and the progressive ageing of many national populations, the discussion of population

policies has increasingly emphasized objectives of raising the fertility level and promoting population

growth. At the same time, rapid population growth remains a concern in countries with persistent high

levels of fertility, whose governments continue their eorts to promote smaller families and facilitate access

to sexual and reproductive health care and services (United Nations, 2013).

2

A/RES/1838 (XVII), 18 December 1962.

3

See https://publichealthreviews.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40985-017-0060-9.

World Population Policies 2021: Policies related to fertility

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Aairs, Population Division

4

In 1962, the General Assembly requested the Secretary-General to “conduct an inquiry among the

governments of States Members of the United Nations and members of the specialized agencies concerning

the particular problems confronting them as a result of the reciprocal action of economic development and

population changes”.

4

To implement this mandate, the Population Division, currently part of the United

Nations Department of Economic and Social Aairs, conducted the rst United Nations Inquiry among

Governments on Population and Development in 1963 and, since then, has periodically gathered information

on ocial government’s views and policies concerning a wide range of population issues, including fertility

and family planning.

World Population Policies 2021: Policies related to fertility, provides a brief overview of past and present

fertility trends and related policies. It features published data from the World Population Policies Database

(box 1) with more recent updates from the United Nations Twelh Inquiry conducted during 2018-2019.

In addition, the report includes an in-depth analysis of fertility trends and related family policies in ve

countries from dierent world regions and with varying fertility levels. e impact of the socioeconomic

disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic on current and future fertility patterns and trends are

then discussed. e report concludes with a set of policy recommendations that governments may wish

to consider in the current context, taking into consideration possible impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

4

A/RES/1838 (XVII), 18 December 1962.

World Population Policies 2021: Policies related to fertility

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Aairs, Population Division

5

Government fertility and family planning policies through 2019

Fertility levels and trends at the global and regional level

Global fertility started to decline since the early 1960s, from about 5.0 births per woman during 1960-1965

to about 3.0 births during 1990-1995 (United Nations, 2019). In 1994, when the landmark Cairo conference

was held, about 46 per cent of the global population, mostly in Europe and Northern America, lived in

countries with below-replacement fertility (under 2.1 births per woman). Total fertility continued to decline

during the decades following the Cairo conference, reaching just under 2.5 births per woman globally

during 2015-2020. In 2019, nearly half of the global population was living in countries with fertility below

the replacement level.

Nonetheless, there have been signicant variations in fertility by development level and by region. In many

developed countries, fertility had declined to below-replacement levels by 2015-2020. In some countries,

including Greece, Italy, Japan and Spain, fertility had been under 1.5 births per woman for several decades.

Whereas all developing countries experienced fertility declines, with many countries reaching replacement

or below-replacement levels, some 40 countries, mostly least developed countries (LDCs), still recorded

fertility levels of more than 4 births per woman.

During 2015-2020, four out of eight world regions had below-replacement fertility, namely Europe and

Northern America, Australia and New Zealand, Eastern and South-Eastern Asia, and Latin America and

the Caribbean. Fertility in sub-Saharan Africa was still high, with, on average, about 4.7 births per woman.

Average fertility levels in Northern Africa and Western Asia (3.5 births), Oceania excluding Australia and

New Zealand (2.9) and Central and Southern Asia (2.4) remained at the intermediate level.

Evolution of government policies on fertility

An increasing number of governments have undertaken eorts to inuence fertility levels over the past

four decades (table 1). While more than half of all countries (52 per cent) did not intervene or did not have

an ocial policy to inuence fertility in 1976, this share had decreased to just over one quarter (27 per

cent) during the period 2015-2019. Moreover, in 1976, only one out of every four countries aimed to lower

fertility and only 9 per cent of all countries undertook eorts to increase birth rates. e growing number

of countries that aim to increase birth rates appear to be a response to growing concerns about population

ageing. Between 1986 and 2019, the proportion of countries that aim to lower fertility has oscillated between

33 and 35 per cent. e share of governments who focus on maintaining their current fertility levels has

remained rather stable at around 10-15 per cent.

Policies concerning the current fertility level and support for family planning

Policies concerning the level of fertility

Globally, through 2019, nearly three quarters of the governments of the 197 Member and non-member

States of the United Nations had policies to inuence fertility levels. Among them, 69 governments had

policies to lower fertility, 55 governments sought to raise fertility, while another 19 governments aimed to

maintain current levels of fertility. Meanwhile, 54 governments did not have such ocial policies concerning

the level of fertility (appendix table).

World Population Policies 2021: Policies related to fertility

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Aairs, Population Division

6

Table 1

Government policies to inuence the level of fertility, 1976-2019 (in percentage)

Year Raise Maintain Lower

No intervention/No

ocial policy

1

Total

1976 9 13 27 52 100

1986 12 10 33 46 100

1996 14 10 42 34 100

2005 20 16 40 24 100

2019 28 10 35 27 100

e available data show a close association between the types of fertility policies adopted by governments

and the prevailing levels of fertility in the country. Among the 69 countries where governments adopted

policies to lower fertility, 10 countries had high levels of fertility and another 50 countries had intermediate

fertility levels. Also, for the 55 countries with policies to raise fertility, 40 had low fertility levels, of which 18

were lower than 1.5 births per woman on average. For the 19 countries that chose to maintain current levels

of fertility, most had fertility levels around the replacement level.

For governments with policies to lower fertility, one major underlying reason was to curb rapid population

growth. Conversely, the major reasons for governments with policies to raise fertility were to counter

population decline and address population ageing. Aside from these specic motivations, a signicant

number of governments stated that ensuring sustainability for future generations was a major driver for

their policies on fertility.

Governments in developed countries were more likely to adopt policies to raise levels of fertility. Most

of these countries had already reached below-replacement fertility levels many years ago. Some countries,

including Greece, Italy, Japan and Spain, have had fertility levels below 1.5 births per woman for decades.

However, 14 out of 30 developed countries with moderately low levels of fertility (between 1.5 and 2.1 births

per woman), such as Australia, Canada, Germany, Sweden, and the United States of America, had no ocial

policies to inuence fertility levels.

Nearly half of governments (46 per cent) in developing countries had policies to lower fertility levels,

whereas about one quarter did not have such policies.

5

Several developing countries from dierent parts

of the world and with varying fertility levels have adopted policies to maintain current fertility levels. ese

include Argentina (2.3 births per woman), Viet Nam (2.1) and the United Republic of Tanzania (4.9).

Most LDCs continue to experience rapid population growth driven mainly by high fertility, particularly in

sub-Saharan Africa. In recent decades, a growing number of governments of LDCs had policies to address

rapid population growth (United Nations, 2017). During the period 2015-2019, nearly 80 per cent of the

LDCs had policies to lower fertility. Some LDCs, which already reached below replacement-level fertility,

such as Bangladesh, Bhutan and Nepal, had policies in place to lower fertility.

Signicant regional variations exist in policies concerning present fertility levels (table 2). In sub-Saharan

Africa and Oceania (excluding Australia and New Zealand), where relatively high fertility and rapid

population growth are more common than in other regions, governments were more likely to adopt policies

to lower fertility. By contrast, countries with persistent low levels of fertility in Europe and Northern Africa,

5

Developing countries without policies to lower fertility included countries with low fertility, such as Brazil, and countries with intermediate fertility,

such as South Africa.

Source: World Population Policies Database, available at: www.un.org/development/desa/pd/data/world-population-policies.

1

Information on “No ocial policy” was gathered separately from “No intervention” starting with the 2015 revision of the World Population

Policies Database. In older revisions, “no ocial policy” was assumed to be included under “No intervention”.

World Population Policies 2021: Policies related to fertility

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Aairs, Population Division

7

as well as in Eastern and South-Eastern Asia, were more likely to adopt policies to raise fertility. Several

countries with moderately low fertility in these two regions did not have an ocial policy to inuence the

level of fertility, including Canada, Czechia, Denmark, Germany, Norway, Sweden, the United Kingdom of

Great Britain and Nothern Ireland and the United States of America. Australia and New Zealand, also with

moderately low fertility, had no such policies in place. Most countries in Latin America and the Caribbean

either did not have policies targeting fertility levels or had policies to maintain current levels.

Table 2

Policies concerning the present fertility level of countries or areas, by region, 2015-2019

(Number of countries or areas in each region and the world)

Region

Policies concerning the present level of

fertility

No ocial

policy Total

(Number of countries or areas)

Raise Lower

Maintain

current

levels

Sub-Saharan Africa 3 35 2 8 48

Northern Africa and Western Asia 9 6 4 5 24

Central and Southern Asia 4 7 3 14

Eastern and South-Eastern Asia 7 3 1 5 16

Latin America and the Caribbean 3 8 6 16 33

Europe and Northern America 27 1 4 14 46

Australia and New Zealand 2 2

Oceania* 2 9 2 1 14

World 55 69 19 54 197

Government’s support to family planning

Access to family planning and reproductive health services is critical to the health of women and children

worldwide. Improving such access can help to prevent maternal deaths and reduce unwanted pregnancies.

Target 3.7 of the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3 on “Good health and well-being: Ensure healthy

lives and promote well-being for all at all ages” calls on countries “to ensure universal access to sexual

and reproductive health-care services, including for family planning, information and education, and the

integration of reproductive health into national strategies and programmes by 2030”. In 2019, 80 governments,

or nearly 80 per cent of 103 governments with available data, reported providing direct support for family

planning. Of these governments, 68 provided both direct and indirect support.

6

In addition, another 18

countries supported the provision of family planning services through non-governmental organizations

only. Together, over 95 per cent of governments among those with available data (103) provided either direct

or indirect support for family planning.

6

Direct support for family planning refers to governments providing contraceptive methods directly through governmental sources, while indirect

support refers to governments providing nancial support for the provision of contraceptive methods by non-governmental organizations.

Source: World Population Policies Database, available at www.un.org/development/desa/pd/data/world-population-policies.

* Oceania excluding Australia and New Zealand.

World Population Policies 2021: Policies related to fertility

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Aairs, Population Division

8

Box I. Data sources and limitations

Data used in preparing this report were obtained primarily from the World Population Policies Database,

maintained since 1976 by the Population Division of the United Nations Department of Economic and

Social Aairs. e most recent update of the database is based on the Twelh United Nations Inquiry among

Governments on Population and Development conducted between September 2018 and August 2019.

e World Population Policies Database provides comprehensive information on national population policies

and programmes for 197 countries or areas, including all 193 Member States, 2 Observer States (Holy See and

State of Palestine) and 2 non-member States (Cook Islands and Niue) of the United Nations. e database

shows the evolution of government’s views, policies and programmes with respect to population size and

growth; population age structure; spatial distribution of populations, internal migration and urbanization;

fertility, reproductive health and family planning; health and mortality; and international migration.

Between 1976 and 2015, the Database was updated biennially by conducting a detailed country-by-country

review of national plans and strategies, programme reports, legislative documents, ocial statements

and various international, inter-governmental and non-governmental sources, as well as by using ocial

responses to the United Nations Inquiry among Governments on Population and Development, conducted

quinquennially since 1963.

e 2017 revision of the Database focused on abortion laws and policies in all countries of the world, based

on a global survey on abortion issues and a careful assessment of legislative documents, conducted jointly

with the World Health Organization during 2016-2017.

Starting with the 2019 revision, the Database has been updated based entirely on ocial government’s

responses to the Inquiry. e 2019 revision of the Database was based on 86 government responses to the

ageing and urbanization module, 107 responses to the fertility, family planning and reproductive health

module, and 111 responses to the international migration module of the Twelh Inquiry, conducted during

2018-2019.

e most recent revision of the Database (2021) is based on 109 government responses to the reproductive

health module, and 89 responses to the international migration module of the irteenth Inquiry, conducted

between November 2020 and October 2021.

In this report, data on selected fertility-related policies from the 2015 and 2019 revisions of the Database have

been combined to create a pooled dataset for all 197 countries or areas covering the period 2015-2019. For

countries or areas with information available in both revisions, the more recent information from the 2019

revision was used. e pooled variables describing the policy situation during the 2015-2019 period include

(a) policies on fertility, (b) measures to improve family/work balance for childbearing and childrearing, and

(c) measures to improve sexual and reproductive health of adolescents.

For other policy questions discussed in this report, including (a) underlying reasons for the current fertility

policy, (b) policies concerning age of marriage or union formation, mother’s age at the time of her rst

birth, and spacing between successive births, (c) ocial views on adolescent childbearing, and (d) policies

concerning the provision of modern contraceptive methods, the data are from the 2019 revision of the

Database for 107 countries or areas that responded to the fertility, family planning and reproductive health

module of the Twelh Inquiry. e most recent (2021) revision of the Database based on the irteenth

Inquiry does not include data on fertility-related policies.

World Population Policies 2021: Policies related to fertility

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Aairs, Population Division

9

Policy measures to lower fertility in high and intermediate fertility countries

Raising the age of marriage or union formation and the age at rst birth, increasing the spacing between

births, and expanding access to modern contraceptive methods are considered to be eective means to

improve sexual and reproductive health and to help reduce fertility levels. Many governments have adopted

some or all of these measures.

High fertility countries

In 2019, there were 11 countries (all LDCs in sub-Saharan Africa) with fertility levels above 5.0 births per

woman (United Nations, 2019). Nine of them also had relatively high adolescent birth rates (ABR), above

100 births per 1,000 women aged 15-19 years.

Among the 11 countries in sub-Saharan Africa with fertility higher than 5.0 births per woman, all except

Somalia had policies to lower fertility, mainly to curb rapid population growth and ensure sustainability for

future generations by: (a) raising the age of marriage or union formation, (b) raising the age of the mother

at the time of her rst birth, or (c) increasing the duration of time between successive births.

Ninety per cent of governments in high fertility countries provided contraceptive methods directly through

public programmes as well as indirectly through government’s permission (80 per cent) or nancial support

(50 per cent) to non-governmental sources. None of the governments in high fertility countries restricted

access to contraceptive methods (gure 1).

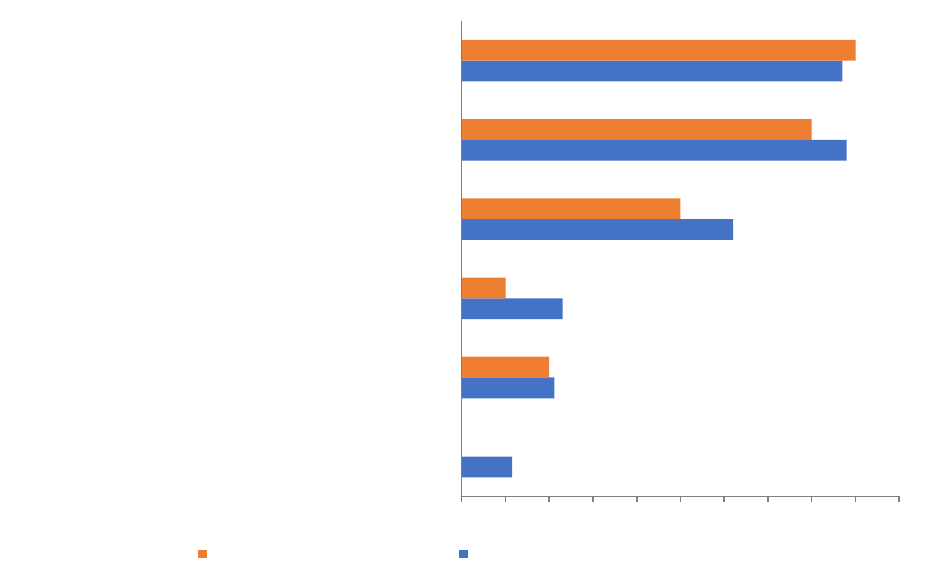

Figure 1

Policy measures taken by governments concerning the provision of modern contraceptive methods, 2019

(in percentage)

12

21

23

62

88

87

0

20

10

50

80

90

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

Restrict access to contraceptive methods

Charge clients for family planning service or commodities

provided through government sources

Subject family planning commodities to duties, import taxes or

other fees

Provide financial support for the provision of contraceptive

methods by non-governmental sources

Permit non-governmental sources to provide contraceptive

methods, without providing financial support to such sources

Directly provide contraceptive methods through government

sources

Countries with high fertility Countries with intermediate fertility

Source: World Population Policies Database, available at www.un.org/development/desa/pd/data/world-population-policies.

Note: Data refer to 10 high fertility countries and 52 intermediate fertility countries in 2019.

World Population Policies 2021: Policies related to fertility

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Aairs, Population Division

10

Intermediate fertility countries

In 2019, for countries covered in the World Population Policies Database, there were 92 countries with

intermediate fertility (between 2.1 and 5 births per woman) (United Nations, 2019). Of these, 29 countries,

mostly in sub-Saharan Africa, had fertility levels higher than 4.0 births per woman. Meanwhile, there were

also a number of countries with fertility approaching the replacement level, including Argentina, India,

Iran, Mexico, Sri Lanka and Tunisia. Over half of these governments (50) had policies to lower fertility

during 2015-2019, while over one h (22) did not have ocial policies. During this time, governments in

a number of countries in Central Asia and Western Asia, had policies to raise the fertility level, including

Saudi Arabia, Iran, Israel, Kazakhstan, Kuwait, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia and Turkmenistan.

About half of the 52 countries with intermediate fertility levels and available data on policy measures to

inuence fertility levels, located in sub-Saharan Africa, Central and Southern Asia, Eastern and South-

Eastern Asia, or Latin America and the Caribbean, sought to raise the age at marriage or union formation

as well as the age at rst birth. Although nearly half of the governments promoted the spacing of birth, few

adopted such a policy in combination with the other two measures.

Most countries with intermediate fertility levels facilitated the provision of modern contraceptive methods,

regardless of whether they had explicit policies targeting fertility. Nearly 90 per cent of these countries

or areas directly provided contraceptive methods through governmental sources, while also nearly 90 per

cent of governments permitted non-government organizations to provide contraceptive methods without

providing nancial support to these NGOs. In addition, over 60 per cent of governments provided nancial

support for the provision of contraceptive methods by non-governmental sources. About three quarters of

governments in intermediate fertility countries provided both direct and indirect support for the provision

of modern contraceptive methods. Only a few governments in these countries (6) applied restrictive policies

in the provision of contraceptive methods, with 12 subjecting family planning commodities to duties, import

taxes or other fees.

Policy measures to improve family/work balance for childbearing and

childrearing in low fertility countries

Among countries with available data on policy measures regarding family/work balance during 2015-2019,

81 countries had fertility below the replacement level (2.1 births per woman), of which 20 had fertility levels

below 1.5 births per woman. While most of these countries were developed countries located in Europe and

Northern America, plus Japan, Australia and New Zealand, some were developing countries located in Latin

America and the Caribbean, Northern Africa and Western Asia, or Eastern and South-Eastern Asia. About

half of the low-fertility countries had adopted policies to raise fertility, (gure 2), about one third of these

countries had no fertility-related policies, mostly in Europe and Northern America or in Latin America and

the Caribbean. Most of these countries were concerned about population decline and population ageing,

and some expressed concerns regarding sustainability for future generations.

All low-fertility countries, with the exception of the United States of America, had introduced paid or unpaid

maternity leave for childbirth with job security. e other four commonly adopted measures were publicly

subsidized childcare (88 per cent), child or family allowances (78 per cent), paid or unpaid parental leave

for childcare at home and paid or unpaid paternity leave for childbirth with job security (both 73 per cent).

In addition, over half of the countries oered exible or part-time work hours for parents or tax credits for

dependent children.

World Population Policies 2021: Policies related to fertility

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Aairs, Population Division

11

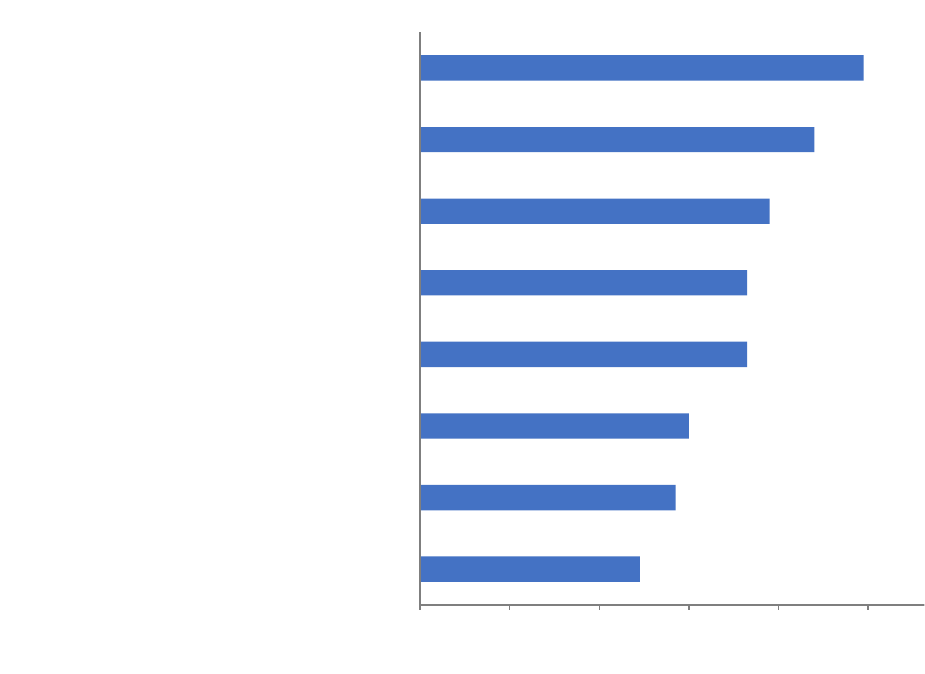

Figure 2

Percentage of governments in low-fertility countries with policy measures to improve work/family balance,

2015-2019

49

57

60

73

73

78

88

99

0 20 40 60 80 100

120

Baby bonus (lump sum payment)

Tax credit for dependent children

Flexible or part-time work hours for parents

Paternity leave for childbirth with job security (paid or

unpaid)

Parental leave for childcare at home (paid or unpaid)

Child or family allowances

Publicly subsidized childcare

Maternity leave for childbirth with job security (paid or

unpaid)

Although many governments did not have ocially promulgated policies on fertility, the above measures

help balance work and family life and are therefore greatly benecial for childbearing and childrearing.

For example, maternity leave, publicly subsidized childcare and exible work arrangements can help many

working parents to have children and remain employed. Tax credits for dependent children and baby

bonuses are measures adopted by some governments as nancial incentives for childbearing.

Increasingly, governments in countries with high and intermediate levels of fertility have also adopted

measures to help balance work and family life. Almost all of these governments have instituted paid or

unpaid maternity leave with job security, while over half of these governments have instituted paid or unpaid

paternity leave with job security, or child allowances.

Measures to improve adolescent sexual and reproductive health

Adolescent pregnancies and births are closely associated with negative outcomes in sexual and reproductive

health and in the social and economic well-being of adolescents. Achieving SDG target 3.7, which calls for

universal access to sexual and reproductive health-care services, including for family planning, information

and education, is critical for improving adolescent sexual and reproductive health.

Source: World Population Policies Database, available at www.un.org/development/desa/pd/data/world-population-policies.

Note: Data refer to 82 countries or areas with below replacement fertility during 2015-2019. Multiple responses possible.

World Population Policies 2021: Policies related to fertility

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Aairs, Population Division

12

Among the 102 countries with data available on government’s views on the fertility of adolescents in 2019,

a large majority (86 per cent) considered it as either a major or a minor concern. Sixty-eight governments,

mostly in countries with adolescent birth rates (ABRs) above 50 births per 1,000 women aged 15-19 years,

considered it as a major concern. is includes almost all governments of countries in sub-Saharan Africa

and in Latin America and the Caribbean that responded to the Inquiry. Another 20 governments, mostly

in countries with ABRs below 50 per 1,000, considered the ABR level to be a minor concern. Another 14

governments were not concerned about the level of the ABR in their countries.

Regardless of their views on adolescent fertility, most governments have adopted policies to improve the

sexual and reproductive health of adolescents, although this was more oen the case in countries with

relatively high levels of adolescent fertility. During 2015-2019, more than three quarters of governments

provided school-based sexuality education, and 55 per cent had adopted measures to expand girls’ secondary

school enrolment and retention, particularly in countries with high levels of adolescent fertility.

7

7

Over 50 births per 1,000 women aged 15 to 19 years.

World Population Policies 2021: Policies related to fertility

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Aairs, Population Division

13

Government policies and related responses: Case studies

is chapter contains ve case studies of policies related to fertility and family planning for countries with a

range of fertility levels from dierent parts of the world, namely Kenya, Argentina, Hungary, Australia and

China. ese case studies provide a more detailed analysis of the evolution of policies related to fertility,

population and family planning that should be understood in the respective historical, cultural and political

context of a given country.

e rst case involves Kenya, a high-fertility country in sub-Saharan Africa with policies to lower fertility

and curb rapid population growth. Kenya was the rst country in sub-Saharan Africa to adopt a family

planning programme in 1967, which helped to bring the country’s fertility level down from 8.1 births per

woman during 1965-1970 to 3.5 births per woman during 2015-2020. e second case, Argentina, also

focuses on government’s eorts to reduce fertility, but with a specic focus on the country’s history of high

adolescent fertility. e third case is that of Hungary, which has experienced a steady decline in population

size since 1980 and has a long tradition pursuing pronatalist policies. e fourth case, Australia, concerns a

country with no ocial population policy but with a range of family policies that support childbearing and

childrearing. e h case, China, examines the renowned one-child policy that was in place from the late

1970s to the mid-2010s for the purpose of lowering the country’s fertility level, as well as its phasing out in

recent years in response to concerns about the rapid ageing of the population.

Policies to lower fertility: Kenya

Kenya has a long tradition of addressing rapid population growth, including eorts to reduce fertility

levels through the promotion of family planning and other indirect government interventions to inuence

demographic trends. Kenya was the rst sub-Saharan country to launch a family planning programme.

e use of modern contraception in the country dates back to the pre-independence period when, in

1957, the Family Planning Association of Kenya (FPAK) was formed. When the FPAK became an aliate

of the International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF) in 1962, the campaign to control fertility was

intensied (Ndeti and Koesoebjono, 1973). Shortly aer gaining independence in 1963, the Government had

several population concerns, rst and foremost of which was high population growth. In 1965, the Kenyan

Government invited the United States-based Population Council to make recommendations on the optimal

rate of population growth, on a programme for achieving this rate, on the administration of the programme,

and on procedures for obtaining funds and technical assistance for carrying out the programme (Population

Council of the United States of America, 1966).

National population policy

A delegation of the Population Council arrived in June 1965 and submitted its report three months later

to the Ministry of Economic Planning and Development (Republic of Kenya, 1967; Population Council of

the United States of America, 1966). e report and recommendations served as the basis for formulating a

national population policy. e aim of the family planning programme would be to achieve a decline in the

population growth rate by limiting the number of children. It recommended that the Government declare

its goal to reduce the population growth rate and to embark on a national programme “to make the means

of limiting the number of their children, as well as assistance to infertile women desiring children, available

to every family” with the ambitious goal of reducing fertility by as much as 50 per cent in 10 to 15 years.

World Population Policies 2021: Policies related to fertility

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Aairs, Population Division

14

National family planning programme

e Kenyan Government incorporated many of the recommendations of the Population Council into

government directives and in the 1966-1970 and 1970-1974 development plans. A National Family Planning

Council was established in February 1967, followed by the launch of a national family planning programme

in May 1967 (Frank and McNicoll, 1987). e family planning programme would make information and

supplies available free of charge through government and private facilities to families wishing to avail

themselves of those services through voluntary means and within religious prescriptions. A timeline of

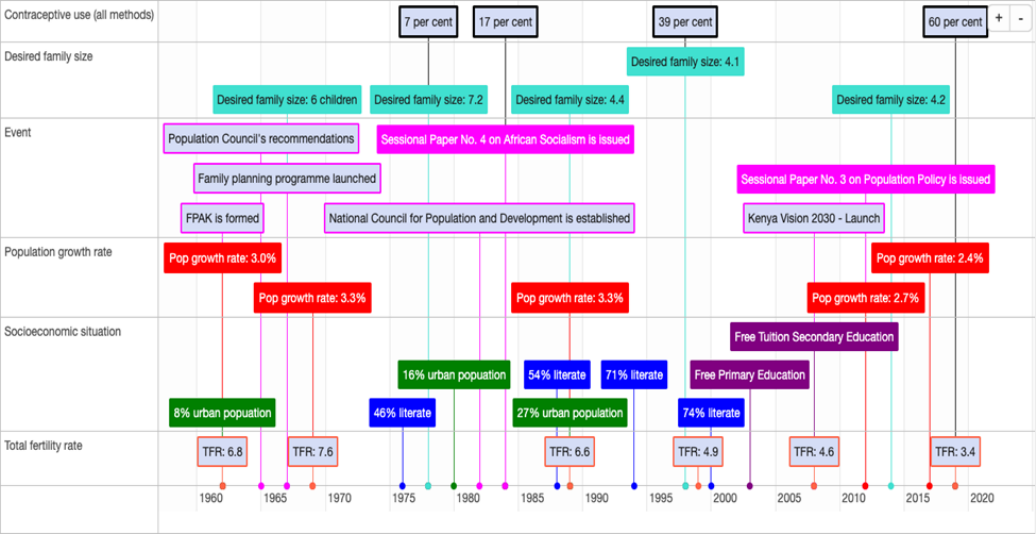

Kenya’s fertility policy is shown in gure 3.

Figure 3

Timeline of fertility policy in Kenya, 1960-2019

Kenya framed population growth and its implications primarily as a national development issue, emphasizing

the voluntary nature of family planning, taking into account individual and family needs as well as social,

cultural and other sensitivities. It integrated population issues in every sector of government and established

the National Council for Population and Development to guide the Government’s ministries, agencies and

sectors in identifying how to integrate population issues in their programmes. It provided the resources and

devolved its implementation down from the Oce of the Vice-President to district planning committees,

district population and family planning committees, and local communities. It encouraged and allowed

private entities and NGOs to participate in implementing the national family planning programmes and

tasked the National Council for Population and Development to coordinate the activities and eorts of the

Government, private agencies, NGOs, and donors. e partnership with the private sector helped to sustain

the family planning services and to reach remote rural areas, particularly when the number of new acceptors

stalled. Kenya became, in a way, a laboratory of policy development and programme implementation in sub-

Saharan Africa.

Source: Prepared by the Population Division of the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Aairs.

World Population Policies 2021: Policies related to fertility

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Aairs, Population Division

15

Kenya accommodated the views of a foreign advisory mission, which stayed and assured the implementation

and modications of the policy. e delegation of the Population Council provided support in several areas

of programme implementation, including training of local personnel in population matters, funding and

supervising critical research. e uninterrupted presence and involvement of the Population Council in

implementing and adjusting the national population policy inspired several foreign agencies, institutions

and donors to participate in Kenya’s eort to manage its own population growth. Many of those entities still

have a physical presence in the country.

Although the family planning programme was conceived to contain population growth, it became eventually

an essential part of the country’s maternal and child health care programmes. Indeed, the implementation of

the national population policy shied to integrate family planning into the national health programme under

the umbrella of maternal and child health. Even as the Programme of Action from the Cairo conference in

1994 shied the emphasis of population policies and programmes towards improving the quality of people’s

lives, including by expanding access to sexual and reproductive health services, Kenya stayed the course in

its eorts to limit population growth and mitigate its negative impacts on national development. Consistent

with the Programme of Action, the high level of adolescent fertility was identied in 1997 as one of the key

challenges that needed to be addressed (Republic of Kenya, 1997).

e National Council for Population and Development and the Population Studies and Research Institute at

the University of Nairobi played critical roles in tracking the progress in the implementation of the national

population policy, assessing its challenges and constraints, providing modications to implementation and

governance, among other activities. ese two national institutions, together with other entities, produced

seminal papers and policy briefs that were the basis of programme implementation.

Perhaps the most critical factor in the evolution and implementation of the national population policy has

been the continued commitment of the Kenyan Government and its emphasis on a participatory process

in formulating, implementing and adjusting the policy. e Government’s eorts were buoyed, to this day,

by sustained donor funding and internal high-level political support. In particular, the government’s role in

population matters was enshrined in the 2010 Constitution (Constitution of Kenya, 2010). In accordance

with the Constitution, every Kenyan is guaranteed to receive health-care services, including for reproductive

health and family planning. e Constitution requires that the programmes and projects are implemented

in close consultation and collaboration with local governments.

In 2012, the Government launched consultations at the local, regional and national levels on the country’s

population policy for national development. Following those consultations, the Government launched a

new policy to manage its persistent rapid population growth and youthful population structure through

a multi-sectoral approach (National Council for Population and Development, 2012). Between 2009 and

2030, the new policy aims to reduce the number of children a woman has over her lifetime from 4.6 to

2.6; increase contraceptive use of modern methods from 40 to 70 per cent; reduce the population growth

rate from 2.5 to 1.5 per cent; reduce the dependency ratio from 87 to 54; and increase the median age of

the population from 17 to 25 years in line with Vision 2030, the 2010 Constitution, the SDGs and other

national goals and international aspirations. e United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) has supported

Kenya’s population policies by strengthening reproductive health services, improving supply chains for

contraceptives, advocacy against gender-based violence, and facilitating integration of population dynamics

into policy formulation (UNFPA, 2021a).

8

8

See https://kenya.unfpa.org/en.

World Population Policies 2021: Policies related to fertility

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Aairs, Population Division

16

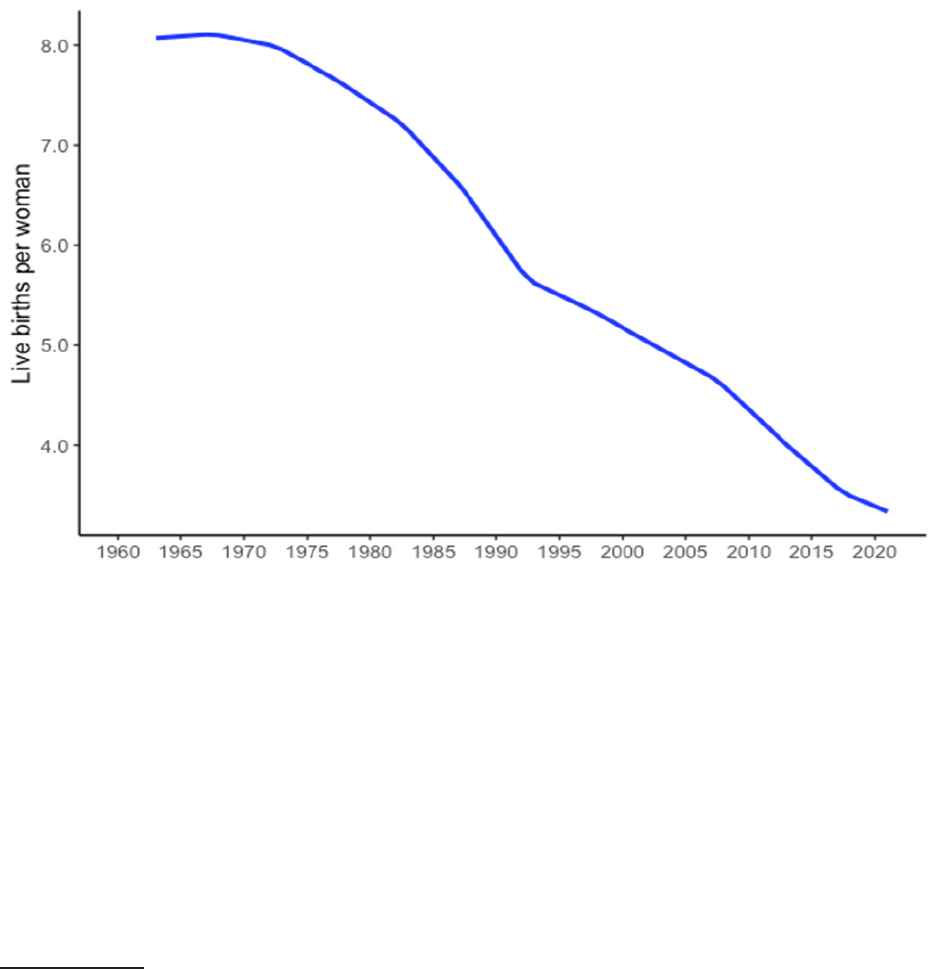

Already, in 2019, the proportion of married women using modern methods of contraception was 56 per

cent, up from 39 per cent in 2009, and the total fertility rate had declined to 3.4 children per woman,

down from 4.5 children per woman in 2012 (gure 4). e Government is cognizant of the challenges

in implementing the policy, which includes the diminished share of resources for population and family

planning activities due to competing or new and emerging issues, such as the ght against HIV/AIDS, and

high levels of adolescent fertility partly attributed to early marriages and polygamy, and during the last two

years, eorts to contain the spread of COVID-19.

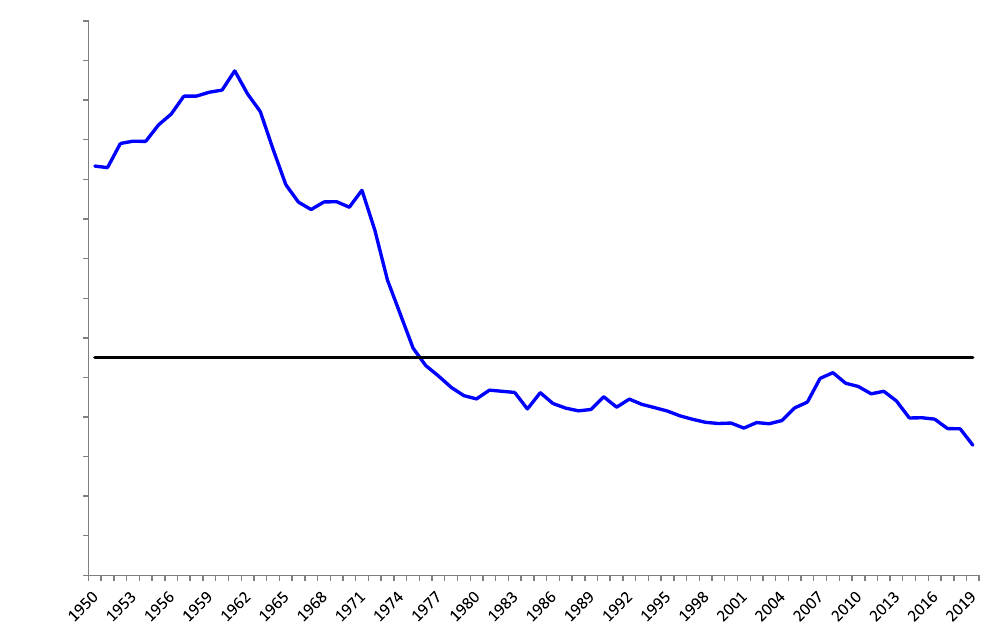

Figure 4

Total fertility rates in Kenya, 1960-2021

When the family planning programme was rst launched, the population was not ready in many ways,

including materially, culturally and psychologically. Nonetheless, the Government and donors consistently

supported the population policy and family planning programme. Generations have since been born and

grown up surrounded by ubiquitous family planning services and information that defy the shame associated

with the use of family planning services in many other sub-Saharan countries.

9

As the population became

more accepting, the family programme succeeded in more than halving the total fertility rate from 7.7 to

3.3 children per woman between 1984 and 2021. By all accounts, Kenya is deemed to have led a successful

family planning programme (Aliyu, 2018; May, 2017), alongside Ethiopia, Madagascar, Malawi, Rwanda,

South Africa and Zimbabwe.

9

A recent study associated the implementation of high-quality programmes in sub-Saharan Africa with rapid changes in reproductive behaviour

(Bongaarts, 2020).

Source: United Nations (2019).

World Population Policies 2021: Policies related to fertility

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Aairs, Population Division

17

Policies to discourage adolescent childbearing: Argentina

Today, Argentina is a low-fertility country that has historically been either a pronatalistor or pro-maternalistic

country, or both (Cepeda, 2014). Like most countries in Latin American and the Caribbean, a majority

of the country’s population ascribe to the Roman Catholic faith, a religion that inuenced many policies,

including those related to fertility. Historically, Argentina is also a country of immigrants, well beyond the

colonization period. Aer gaining independence in 1816, Argentina became one of the world’s top receivers

of immigrants, most of them from Spain, Italy and other European countries. Despite its relatively overall

low level of fertility since the twentieth century, Argentina exemplies the persistence of high fertility among

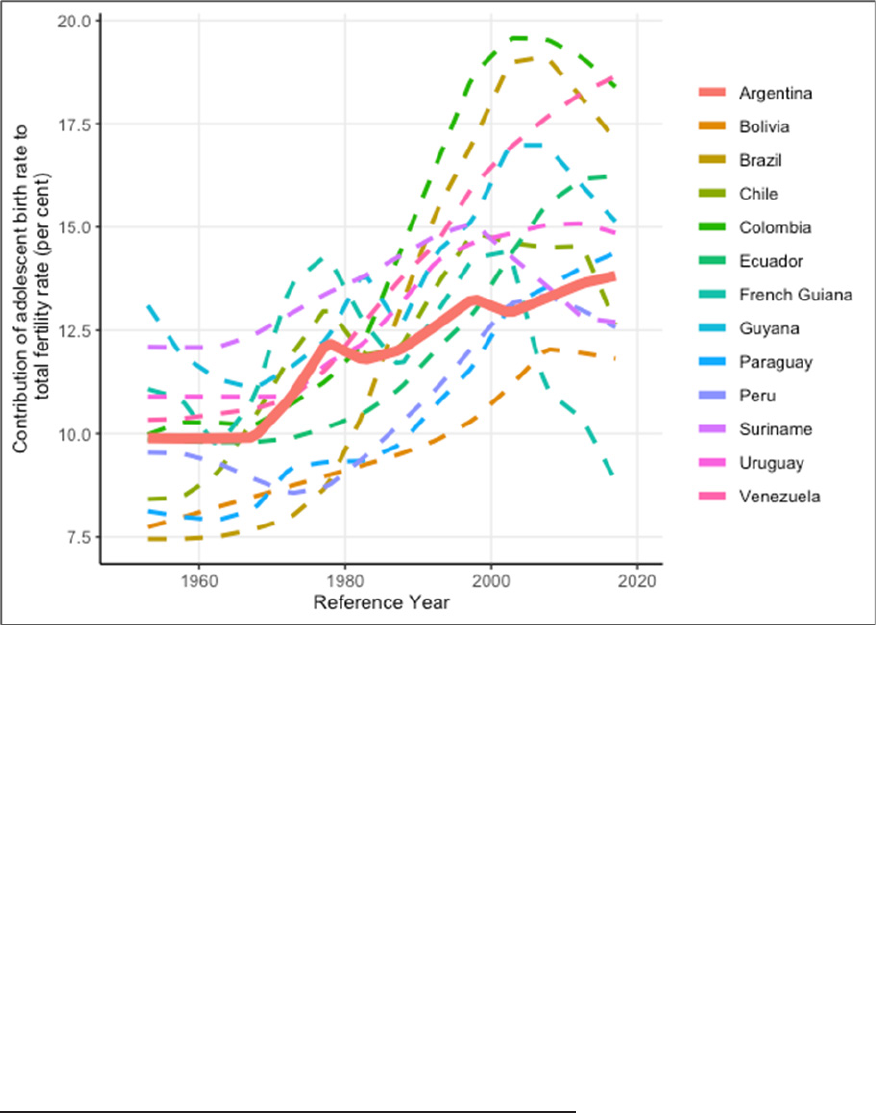

adolescents in the region (gure 5) and an increasing contribution of adolescent births to total fertility.

Population policies in the country should be placed within the larger context of major socio-political

changes in Argentina (Novick, 2001). In the period preceding 1930, women were mostly conned to family

roles. Aer 1930, women were granted some liberties and civil rights, were allowed into the labour force and

given certain protections in the workplace: their employment could not be terminated because of marriage,

they were granted maternity protection, including medical care and nancial compensation, and pregnant

women were prohibited to work during the 30 days preceding a birth and during the 45 days following a

birth.

First population congress, 1940

At the rst population congress, or Primer Congreso de la Población (PCP), convened in 1940, major concerns

were raised about the slowdown in population growth. During the period 1935-1940, the population growth

rate had declined to 1.6 per cent, down from 2.7 per cent for the period 1925-1930. e slow population

growth rate and the decline in fertility were seen as posing serious limitations for the future economic

growth of the nation (Novick, 2001).

e PCP generated a lot of media attention, editorial commentary and public discussions. It was a watershed

event that informed population policy in the ensuing years. During 1945-1955, the Government assumed

greater responsibility for women and children’s health (Novick, 2001; Ramacciotti, 2003). It provided

subsidies for births, granted employment preference in hiring and retention of parents and exempted

or reduced taxes for large families (Ramacciotti, 2003). Children previously classied as legitimate or

illegitimate were now classied as born in wedlock or out of wedlock, with other discriminatory categories

and designations phased out. For the rst time, parents who did not meet their paternal obligations could

be imprisoned (Novick, 2001).

From the 1950s through the early 1970s, the Government continued to expressly declare its responsibility

for the health of mothers and children, implementing a policy that guaranteed free medical care and basic

foodstus. In 1974, the Government created a national commission on demographic policy, the Comisión

Nacional de Política Demográca, to support population growth. In that same year, at the World Population

Conference in Bucharest, Argentina joined other countries in the argument against the Malthusian view of

population growth. In the meantime, however, adolescent fertility had begun to become a concern in the

1970s, a decade later than in Europe and the United States of America (Gogna and others, 2008), because of

the strong pronatalist sentiments in Argentina.

Petracci, Ramos and Szulik (2005) have summarized the evolution of policies on reproductive health in

Argentina since the 1980s as involving three phases. First, the gradual opening of public space and receptivity

of reproductive health issues. Second, the passing of a national sexual and reproductive health law. ird, the

successful development of public policy and programmes, despite the pressures from conservative groups

and contradicting policies over the lifetime of several dierent governments to date.

10

10

As Robinson and Ross (2007) have observed, governments implement policies by enacting laws, creating implementing agencies, and expending

public resources. ese actions provide the framework within which policy responses and endurance occur. Argentina is emblematic that the

World Population Policies 2021: Policies related to fertility

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Aairs, Population Division

18

Figure 5

Contribution of adolescent birth rate (births to women aged 15-19 years) to total fertility rate, South American

countries (in percentage)

International agreements

Following the ratication of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against

Women in 1985, and the agreements reached at the International Conference on Population and Development

in 1994 and the Fourth World Conference on Women in 1995, a strong public consensus emerged around

key reproductive health issues (Petracci, Ramos and Szulik, 2005). Aer the unsuccessful attempt to include

a section penalizing abortion in the amendment of the National Constitution in 1994, many provinces

and municipalities established local reproductive health programmes, undeterred by the position against

abortion adopted by the Argentine Government together with the Vatican in Cairo in 1994.

11

Adolescent fertility as an issue

e adolescent fertility rate rose and peaked towards the end of the 1980s at 80 births per 1,000 adolescent

girls.

12

By 2001, Argentina was experiencing a serious socioeconomic and political crisis, with almost half

of its population living in poverty and 19 per cent of the labour force unemployed. Millions of young people

were neither in school nor working (Reina and Castelo-Branco, 2014).

political and social context might change but, oen, the policy responses endure.

11

Novick (2001) has observed that the Argentine Government’s position against abortion at the Cairo conference in 1994 did not necessarily imply

a pro-birth policy at the domestic level.

12

Census and survey data show that half of adolescent mothers aged 15-19 were living with their spouse or consensual partner in 2001 and 1 in 10

were divorced or separated (Gogna and others, 2008; López, 2006).

Source: United Nations (2019).

World Population Policies 2021: Policies related to fertility

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Aairs, Population Division

19

In 2003, the Government created a National Programme for Sexual Health and Responsible Procreation,

which was tasked with the development and implementation of public policies on sexual and reproductive

health. e programme is aimed at the population in general, without discriminating against any sector

or population group.

13

e tasks specic to adolescents included the prevention of unwanted pregnancy

and the promotion of sexual health. is programme distributes contraceptive commodities free of charge

throughout the country. Under the 2006 National Comprehensive Sexual Education Programme, (Ministerio

de Justicia y Derechos Humanos, 2006), comprehensive sexual education became a right of all children,

adolescents and young people who attend the public and private schools at the primary and secondary levels

(Malnis, 2018).

14

Argentina launched a conditional cash transfer programme (Asignación Universal por Hijo) in 2009, a

monthly cash allowance for each unmarried child under the age of 18 years—or with no age limit for a child

with a disability—whose household members are unemployed or informal workers. e programme provides

the subsidy to only one of the parents, prioritizing the mother, and for up to ve children (Administración

Nacional de la Seguridad Social, 2021; Badaracco, Gasparini and Marchionni, 2016).

Discussion

Argentina experienced a peculiar trend in fertility levels. e fertility transition in Argentina occurred long

before hormonal contraceptives were available, indicating that fertility was traditionally controlled by the

use of periodic abstinence, withdrawal and abortion (Gogna and Pantelides, 2009). Despite the decades-

long pro-maternal and pronatalistpolicies and programmes, and the intermittent ban on family planning

activities and restrictions on abortion, the present fertility levels were reached, in part, by using modern

contraception and abortion. e overall fertility decline was associated mostly with a reduction in inequality

and poverty in Argentina and in Latin America more generally (Badaracco, Gasparini and Marchionni,

2016).

e current level of fertility in Argentina is comparable to average total fertility rates in the Latin American

and Caribbean region. Concern remains, though, about the trends in the adolescent fertility rate, which

are above the regional average, despite the policies and programmes that have been implemented. e

adolescent birth rate has declined at a slower pace than the total fertility rate and it remains high at 61.7 per

1,000 adolescent women, sustained by the high birth rates among girls in the poorer socioeconomic strata,

a reection of inequity (Reina, and Castelo-Branco, 2018). Estimates of the contribution of abortion to

fertility decline show that in the late 2000s, an average of 450,000 unsafe abortions per year were performed

in Argentina, or 0.64 abortions per birth, suggesting a shortfall in policy eectiveness or conicting impacts

on wanted fertility.

15

e availability of contraceptive commodities and services is not necessarily associated with fertility

intentions. Studies in Argentina and elsewhere have observed that many women and adolescents—especially

those in the lower socioeconomic strata—desire motherhood from a very young age because it increases self-

esteem, social approval and prestige within a woman’s family and community ( UNICEF, 2001; López, 2006;

Dyer, 2007; Ombelet and others, 2008; Kane and others, 2019). A study by López (2006) shows that three out

of ve sexually active adolescent girls aged 15-19 were using contraception in Argentina, although a majority

were already mothers, some with more than one child. Subsequent research shows that more than 80 per

cent of adolescents in Argentina were not using a contraceptive method when they became pregnant, even

though they did not necessarily want to have a child (Reina, and Castelo-Branco, 2018; Gogna and others,

2008). Also, access and use of contraception by adolescents in Argentina is still controversial, particularly in

13

e law that established the National Programme of Sexual Health and Responsible Procreation is reproduced in Reina and Castelo-Branco (2014).

14

However, 75 per cent of the adolescents in the last two years of high school indicate that the school does not oer them sex-education topics that

are of interest and relevant to them (Equipo Latinoamericano de Justicia y Género (ELA), 2020).

15

Even though abortion is legally restricted, studies in 2008 show that 5 per cent of adolescents in Argentina had an abortion (Gogna and others,

2008) and that 16 per cent of the hospital admissions for abortion complications were girls under 20 years of age (Reina and Castelo-Branco, 2014).

World Population Policies 2021: Policies related to fertility

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Aairs, Population Division

20

some poor provinces where the inuence of the Catholic Church and other conservative forces is still strong

(Gogna and Pantelides, 2009).

ere are suggestions that the high levels of adolescent fertility in Argentina could be partly the unintended

result of policies and programmes, such as the cash transfers for young mothers, that were designed to

mitigate the negative association between socioeconomic inequalities and adolescent fertility (ECLAC, 2012;

Garganta and others, 2017). Young mothers are then most likely to use family planning when the challenges

of parenthood dawn on them. Also, unlike countries such as Mexico, where adolescent births occur mostly

within marriage or a union (Quick, 2014), childbearing among adolescents in Argentina appears to have

become more socially tolerable, especially aer the Government ended the discrimination against children

born out of wedlock (Novick, 2001).

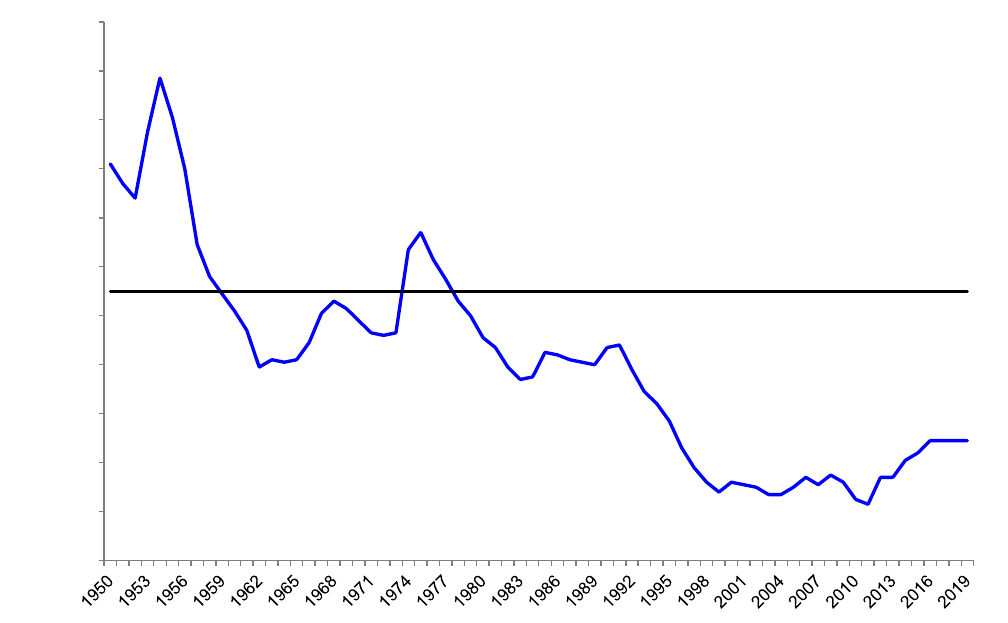

Policies to encourage childbearing and raise fertility: Hungary

Since the late 1940s, Hungary has continuously implemented policies to raise fertility, with short and

temporary changes towards less pronatalist approaches. Nonetheless, fertility in Hungary declined below

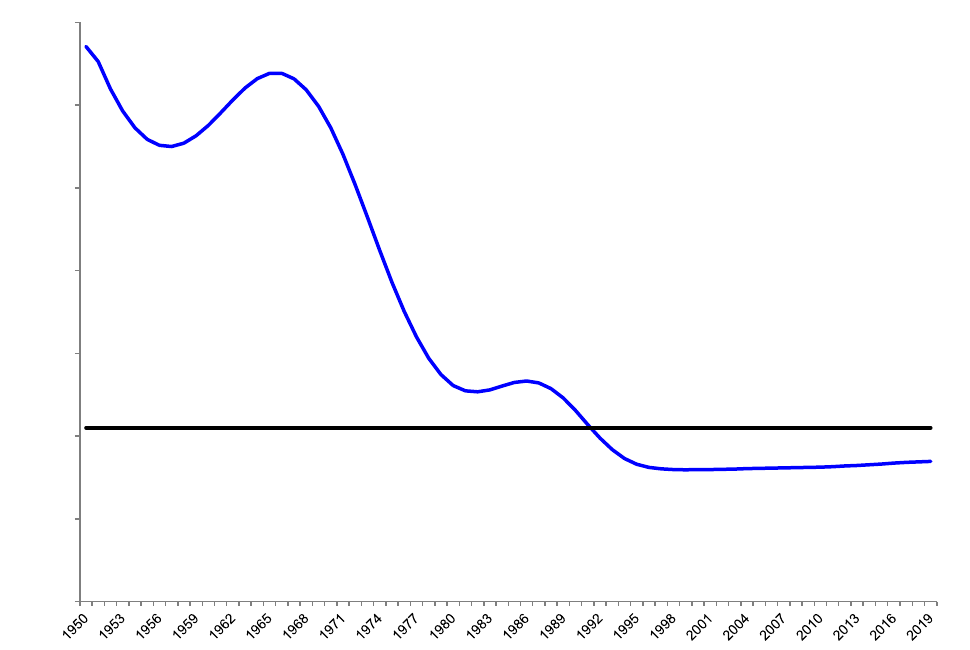

the replacement level for the rst time in 1960 and has continued to decline further to about 1.5 births per

women during 2015-2020. Unlike many other developed countries, Hungary experienced only a moderate

baby boom aer the Second World War. e total fertility rate was 2.6 births per woman in 1950, but quickly

declined below the replacement level in the 1960s, reaching a level of 1.8 births in 1962. e country’s

population size has been falling since 1980.

Policies intended to raise the fertility level and promote population growth were adopted by the Hungarian

Government both during the period of the centrally planned economy (1949-1989) and during the period

of the current market economy (1989 to present). ere were frequent changes in policies and programmes

associated with dierent political regimes during the 1990s and early 2000s (Spéder, 2015). e current

Government coalition, which has been in power since 2010, has steadily expanded policies to encourage

families to have more children.

Maternity and family allowances introduced in 1967 and 1973 may have been the cause of a rebound that

raised fertility levels for a short period even above the replacement level in the mid-1970s. However, past

medium-term trends towards lower fertility resumed quickly thereaer and stabilized around 1.8 births

until the early 1990s. e 1990s were marked by the collapse of the Soviet Union and the transition to

a new political system that also included economic reforms, including the adoption of a scal austerity

programme that led to a sharp economic downturn. e constraints and uncertainties associated with these

drastic political, social and economic transformations led many couples to delay the starting of a family and

childbearing in general. Total fertility dropped to a low level of 1.3 births per women in 1999 and stayed

around that level until 2011. e country’s total fertility rate has risen slightly to nearly 1.5 births per women

over the past ve years (gure 6).

World Population Policies 2021: Policies related to fertility

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Aairs, Population Division

21

Figure 6

Total fertility rates in Hungary, 1950-2019

1.0

1.2

1.4

1.6

1.8

2.0

2.2

2.4

2.6

2.8

3.0

3.2

Live births per woman

Responding to changing population dynamics, population and family policies in Hungary have evolved

over time. In the 1950s, the Government rst introduced policy measures restricting access to abortions

and contraception that were quickly relaxed in response to public objections to these measures. is led

to an increase in the number of abortions and a decline in the number of births until the early 1960s

(United Nations, 1989a). In 1967, the Government introduced the maternity allowance, a paid maternity

leave with job security for mothers to take care of a young child until the child’s third birthday. In 1973,

family allowances were introduced, whereby families and young couples received benets to improve their

housing conditions, such as low-rent public housing and interest-free housing loans. Later on, in 1985, the

Government adopted new population policies to address fertility decline and negative population growth.

e measures included a wage-adjusted parental leave, tax relief for large families and the expansion of the

family allowances to unemployed parents.

Following the end of socialism in Hungary, successive governments continued the family policies to support

families aimed at raising fertility, even though priorities and the extent of support evolved (Spéder, 2015).

e current Government, in power since 2010, has a strong demographic focus with an objective to raise

fertility to a level of 2.1 births per woman by 2030. e existing family welfare system has been modied and

expanded over the past decade and currently provides family allowances and tax credits as well as universal

maternity leave, childcare support and exible employment to help parents return to the labour market.

However, due to the complexity of the various programmes, many Hungarians are reportedly unfamiliar

with them (Albert, 2018). e current scope of public nancial support for families and children in Hungary

ranks second only aer France among OECD countries as a percentage of GDP (OECD, 2021).

Source: Hungary Central Statistical Oce (2021).