Marshall University Marshall University

Marshall Digital Scholar Marshall Digital Scholar

Faculty Submissions

2021

Unfaithful Representation: Understating Accounts Receivable In Unfaithful Representation: Understating Accounts Receivable In

The Name Of Conservatism The Name Of Conservatism

Timothy G. Bryan

Follow this and additional works at: https://mds.marshall.edu/facstaff_submissions

Part of the Accounting Commons, and the Business Law, Public Responsibility, and Ethics Commons

Accountancy Business and the Public Interest 2021

52

Unfaithful Representation: Understating Accounts Receivable In The Name Of

Conservatism

Timothy Gordon Bryan, DBA, CPA

Assistant Professor of Accounting

Lewis College of Business, Brad Smith Schools of Business

Marshall University, USA

Mark A. McKnight, Ph.D., CFE

Associate Professor of Accounting

Romain College of Business, University of Southern Indiana, USA

Email: mamcknight@usi.edu

Robert Houmes, Ph.D., Professor of Accounting,

Thomas R. McGehee Endowed Chair of Accounting

Davis College of Business, Jacksonville University, USA

Abstract

This research empirically examines the relationship between conservatism in

accounting and the allowance for doubtful accounts. A sample of companies’ financial

data related to the allowance for doubtful accounts and bad debt expense in the

chemical and allied products manufacturers industry, SIC 28, for the period from 2005

through 2017 was obtained. The results of analysis of this data indicate that the

allowance for doubtful accounts is overstated in these firms and has become more

overstated since 2004. This research is important as few have researched the

allowance for doubtful accounts, and that research has not considered the allowance for

doubtful accounts as a percentage of the accounts receivable balance.

Keywords: bad debt, allowance for doubtful accounts, conservatism, write-off, cookie-

jar reserves

Introduction

Conservatism permeates accounting standards. Generally, conservatism provides that

accountants tend to wait until virtual certainty for recording good events while merely

probable for recording bad events. Statement of Financial Accounting Concepts

(SFAC) No. 2 states that conservatism is a reasonable reaction to unknown, and if

multiple equally possible estimates are available then the less optimistic estimate

should be recognized (FASB, 1980). Conservatism refers to the adage “anticipate no

profits and provide for all probable losses” (Bliss, 1924). This definition of conservatism

has been restated to report the lowest possible alternative value for assets but the

highest possible value among alternatives for liabilities (Watts and Zimmerman, 1986).

The research focuses on conservatism as it relates to the allowance for doubtful

accounts in the chemical and allied products manufacturers (SIC 28) industry due to the

number of publicly traded firms in the industry and their relatively large accounts

receivable balances. The U.S. Department of Labor indicates that businesses in this

group include those producing:

Accountancy Business and the Public Interest 2021

53

• Industrial inorganic chemicals

• Plastics and resins

• Drugs

• Soaps, detergents, cleaning preparations and toiletries

• Paint, varnishes, lacquers and enamels

• Industrial organic chemicals

• Agricultural chemicals, and

• Miscellaneous chemical products

This research studies the understatement of accounts receivable and the continually

increasing level of understatement. This research is important because only a few

have researched the allowance for doubtful accounts even though accounts receivable

is a material balance sheet account for numerous companies. McNichols and Wilson

(1988) model bad debt expense based on three economic determinants that explain a

significant portion of bad debt expense. Others find that firms manage earnings using

receivables (Teoh et al., 1998; Marquardt and Wiedmand, 2004; Caylor, 2010).

Jackson and Liu (2010) performed extensive research on the allowance for doubtful

accounts across broad industries from 1980 through 2004. However, no research has

been conducted since. Also, their research did not consider the allowance for doubtful

accounts as a percentage of the accounts receivable balance.

Accounts receivable represents amounts due from customers because of credit sales to

the customers and is typically recorded as a current asset on the balance sheet

(Financial Accounting Foundation, 2017e). For companies that typically extend such

credit to customers, accounts receivable can be material to their financial statements.

Accounts receivable are reported on the balance sheet at net realizable value, which is

the estimated amount a firm can expect to collect from its customers (Gordon et al.,

2016). The net realizable value is reported as the asset account of accounts receivable

less a contra-asset account of allowance for doubtful accounts on the balance sheet

(Gordon et.al., 2016). Therefore, the allowance for doubtful accounts is an estimate by

the firm of the amounts it will not collect from customers.

Accounting standards generally accepted in the United States require companies to

estimate losses (in this instance bad debt expense) when it is probable that a loss has

occurred, and the amount of the loss can be reasonably estimated (Financial

Accounting Foundation, 2017e). Estimating the probable bad debt should be based on

the company’s prior experience, information about customers, current economic

conditions, or industry standards (Financial Accounting Foundation, 2017e).

Companies record bad debt related to accounts receivable with a debit to bad debt

expense (an income statement account) and a credit to allowance for doubtful accounts

(a balance sheet account) (Gordon et.al., 2016). When conditions become known that

a customer will not pay an outstanding receivable, the company will “write-off” the

receivable or remove the balance from the balance sheet. Since the dollar amount of

write-offs related to accounts receivable has already been estimated through the

allowance for doubtful accounts, the method of recording the write-off is to reduce the

Accountancy Business and the Public Interest 2021

54

accounts receivable balance by the now known unpaid account through a credit to the

account and reduce the allowance for doubtful accounts through a debit by the same

amount (Gordon et.al., 2016).

There are generally two broad methods of estimating probable bad debt based on prior

experience: one is based on a percentage of the current period’s credit sales and the

other is based on a percentage of outstanding receivables (Gordon et.al., 2016). Prior

research has considered the reasonableness of bad debt expense as a percentage of

sales but did not consider the reasonableness of the allowance for doubtful accounts as

a percentage of outstanding receivables (Jackson and Liu, 2010). Given that firms

estimate bad debts using one of two methods and both the balance sheet and income

statement are impacted, this research will add to the body of knowledge by investigating

both the income statement impact and the balance sheet impact.

Literature Review

Conservatism is studied and utilized in two forms: conditional and unconditional. The

significant difference between the two is unconditional conservatism is based on

information known at the beginning of an asset’s life while conditional conservatism is

based on information obtained in future periods (Basu, 2005).

Conditional conservatism happens when an event triggers significant negative news to

be recognized in financial statements; however, similar significant positive news does

not trigger recognition in the financial statements. As an example, information leading

to the belief that fixed assets are impaired would result in a loss being recorded;

however, information leading to the belief that fixed assets have significantly

appreciated would not result in a gain being recorded (Financial Accounting Foundation,

2017a). Another example of conditional conservatism would include lower of cost or

market for inventory. In this practice, inventory value is lowered if market conditions

indicate the original cost exceeds current replacement cost (Financial Accounting

Foundation, 2017b). The opposite is not reported when inventory replacement costs

become higher than the original cost of inventory (Financial Accounting Foundation,

2017b).

Another example of conditional conservatism would be loss contingencies. Loss

contingencies result when the likelihood of a future event related to a current or prior

period will cause economic loss to an entity is probable (Financial Accounting

Foundation, 2017c). If the amount of the loss can be reasonably estimated and the

likelihood of the loss is probable, then the entity should record a charge (loss) to income

(Financial Accounting Foundation, 2017c). However, a gain contingency that meets all

the same requirements of a loss contingency, except it results in probable economic

benefit, is not recorded (Financial Accounting Foundation, 2017d). This contrasting

treatment is conservatism.

Unconditional conservatism, as the name suggests, does not occur after a specific

economic event. Rather, unconditional conservatism is an accounting principle being

applied consistently and regularly (Ruch and Taylor, 2015). An example of

Accountancy Business and the Public Interest 2021

55

unconditional conservatism would be the last in first out (LIFO) method of inventory cost

flow. Under a typical inflationary environment, LIFO results in lower inventory values

than other inventory cost flow methodologies because it expenses the most recent costs

and values inventory at the oldest costs (Gordon et.al., 2016). Accelerated depreciation

expenses most of an asset’s value early in the asset’s useful life and represents

unconditional conservatism. Other examples of unconditional conservatism would

include expensing research and development costs and expensing advertising costs

(Ruch and Taylor, 2015).

Conservatism in accounting is an almost ancient practice. Sterling (1967) believes

conservatism in accounting is the most widespread and oldest accounting principle. An

analysis of Italian and German merchant records dating as far back as the early

fifteenth century describes applying conservatism primarily to reduce taxes (Penndorf,

1930). In the late 16

th

century, Benedictine monks published accounting guidelines

including accounting for inventory, their guidance was that goods should always be

valued at a standard price lower than market to always sell at a profit (Vance, 1943). In

the late 18th century, Prussia required valuation of inventory at (lower of) cost or market

to combat fraudulent over-reporting of inventory (Vance, 1943). Vance (1943) concludes

his historical research of inventory cost methods that they grew out of the needs of

businessmen. Watts (2003a) believes conservatism has arisen out of four business

needs: contracting, litigation avoidance, taxes and regulation.

Basu (1997) explains that conservatism arises naturally between parties in a contractual

arrangement. The natural tendency toward conservatism stems from opposing benefits

from contracting parties or asymmetry. Conservatism is a means of addressing the

differing information available to contracting parties, asymmetric payoffs, varying time

frames and limited liability or benefits (Watts, 2003a).

Several have suggested the benefit of accounting conservatism for efficiency in

contracting debt specifically (Watts, 2003a; Watts, 2003b; Basu, 1997; Zhang, 2008).

The general idea with lending is lenders do not benefit from better than expected news;

however, they do benefit from conservatism being applied by signaling potential default

(Zhang, 2008; Basu, 1997). Another way of looking at this is debt holders do not benefit

if a firm does very well and produces higher than expected net assets (Watts, 2003a).

The debt holders only receive the re-payment of their loan to the firm. However, if a firm

has lower than anticipated net assets (an amount insufficient to re-pay the debt), the

debt holders lose. This asymmetric benefit for debt holders causes the creditors to be

more concerned with bad news resulting in inadequate net assets (Watts, 2003a).

Therefore, creditors benefit from firms employing conservatism. Creditors also tend to

place some type of lower limit on net assets that allows the creditors to call the debt and

restrict management’s actions that could lower net assets (Beneish and Press, 1993),

(Watts, 2003a). The financial crisis and credit crunches led to firms needing to raise

financing (Ivanshina and Scharstein, 2010), and several have found that firms

employing conservatism enjoy lower financing costs (Ahmed et al., 2002; Zhang, 2008;

Francis et al., 2013).

Accountancy Business and the Public Interest 2021

56

Positive accounting theorists attempt to explain and forecast actual accounting practices

by firms rather than prescribe what should be done (Watts and Zimmerman, 1978).

Positive accounting theory believes that conservatism in accounting is an efficient

mechanism for contracting and governing firms to address information asymmetry and

agency problems (Watts, 2003a; LaFond and Watts, 2008). This means boards can

govern firm management better using accounting conservatism (Ahmed and Duellman,

2007). Agency costs happen when managers or other firm-related parties consider or

maximize their own payoffs instead of the firm’s (Watts, 2003a). Contracts between the

parties requiring certain conservative accounting methodologies can help firms reduce

these agency costs (Watts and Zimmerman, 1986). Managers naturally have

motivations to prevent losses (or even hide them) to avoid being reprimanded, have

bonuses reduced or being fired. Basu (1997) believes managers utilize conservative

accounting to avoid compensation losses due to their own bias. Yao and Deng (2018)

find that managers will manipulate working capital components, including accounts

receivable, for managing earnings and resulting incentives. Also, earnings that have

been measured conservatively can result in future, long-term benefits to managers

through deferred compensation plans at retirement (Smith and Watts, 1982).

Watts (2003a) believes all types of conservatism benefit contracting by constraining

management’s behavior. Some believe that only conditional conservatism improves

contracting efficiency because it provides parties with new information; however,

unconditional conservatism does not provide outside parties with new information (Ball

and Shivakumar, 2005).

Firms that utilize conservative accounting can have reduced litigation costs because a

firm is more likely to face shareholder litigation by overstating net assets than by

understating net assets through conservatism (Watts, 2003a). Watts (2003a) also

believes conservatism reduces the possibility of regulators and standard setters being

criticized by placing value on conservatism as a constraint to managers. Leftwich

(1995) found that most of the FASB agenda items and decisions from the mid-seventies

to the mid-nineties resulted in delayed income recognition and increased liabilities.

Givoly and Hayn (2002) believe this focus by the FASB was due to the ever-increasing

litigious environment in the United States. Even earlier, Skinner (1994) found managers

are more likely to let investors know about bad news than good news to avoid litigation.

Similar to the Italian merchants trying to lower their ad valorem taxes, Basu (1997)

asserts most forms of unconditional conservatism arose from tax benefits. In the early

20

th

century, U.S. tax law provided for deductions of reasonable amounts for the

exhaustion or wear and tear of property used in business (Saliers, 1939). Saliers

(1939) points out that not long after this, businesses started utilizing the conditional

conservatism of lower of cost or market for inventories more frequently and the

unconditional conservative double declining balance method of depreciation. Double

declining balance method of depreciation uses a rate that is double the straight-line rate

applied to the book value (cost less accumulated depreciation) of an asset resulting in

much higher depreciation early in an asset’s life and lower depreciation later (Gordon

et.al., 2016). The inventory cost flow method of LIFO developed out of an older

Accountancy Business and the Public Interest 2021

57

inventory method referred to as base stock method which was not allowed for

calculating income taxes (Davis, 1982). The use of LIFO by firms increased

substantially following World War II in response to higher inflation and to lower income

taxes (Davis, 1982). Since income taxes were not introduced until the late 18

th

century,

the use of unconditional conservatism methods such as these is relatively new

compared with some conditional conservatism like the lower of cost or market for

inventory (Basu, 2005). This leads to the assumption that income taxes have played a

major role in the acceptance and use of unconditional conservatism in accounting.

Firms can lower their taxes by employing conservatism because conservatism

recognizes expenses relatively early and delays revenues.

In some cases, conservatism arose out of regulatory environment. Boockholdt (1978)

notes that nineteenth and early twentieth century rail companies in the United States

were subject to tremendous regulation by the federal government. Much of the

regulation had to do with logs of shipments, but railroad companies also had to report

results of operations and financial condition in voluminous annual reports. To reduce

the likelihood of valuation adjustments being made by examiners or auditors for

reasonable valuation of assets and because rail companies had tremendous

investments in fixed assets, most railroad companies adopted the double declining

balance method for depreciation (Boockholdt, 1978).

Earnings that repeat over time are persistent. Applying conservatism, however, results

in asymmetry in the timeliness of information and persistence of earnings. Further, bad

news is timelier, yet less persistent, while good news is less timely but more persistent

(Basu, 1997). Another way to put this is bad news does not necessarily repeat; goods

news often repeats. Research has indicated that conservatism understates accounting

values of equity compared to fair values of equity. That is, assets and revenues are

understated, and liabilities and expenses are overstated (Ruch and Taylor, 2015).

However, as noted above, accounting practices and standards still utilize the concept of

conservatism as the reasoning.

One element of accruals that investors will look toward is cash flows. Cash flows are

often lagged by one or more periods from resulting accruals (Houmes and Skantz,

2010). In the case of applying conservatism, the bad news is recorded before the

resulting decrease in cash flows or expenditure (Byzalov and Basu, 2016).

Balachandran and Monhanram (2011) observe that utilization of conditional and

unconditional conservatism has increased. They note a general trend of declining value

relevance during the same period. However, they find no evidence of a decline in value

relevance of accounting information in firms that also had increased conservatism.

In its supersession of SFAC No. 2 through SFAC No. 8, the Financial Accounting

Standards Board (FASB) comments that conservatism is excluded from the new

financial accounting concepts because it directly conflicts with neutrality (FASB, 2010).

Conservatism has deep roots in accounting perhaps dating back hundreds of years

(Basu, 1997; Watts, 2003a). Under the concept of neutrality, conservatism has no

Accountancy Business and the Public Interest 2021

58

place in accounting standards (FASB, 2010). Conservatism is an intentional

understatement of a firm’s net worth which is not a neutral viewpoint. In establishing

SFAC No. 8, the FASB believes financial information should be neither understated nor

overstated (FASB, 2010). Both understatement and overstatement impair outside

users’ ability to make decisions related to a firm which is the ultimate objective of

financial reporting. Conservatism, by definition, can understate income and assets.

The FASB conclusion was this is not faithful representation. They believe neutrality

should be the goal of financial reporting. It should be noted, however, that a SFAC is a

guideline for establishing standards and not a standard in and of itself. Generally

accepted accounting principles in the United States still contain conservatism across

many areas as discussed above and many would argue is a necessary part of

accounting standards (Watts, 2003a; Watts, 2003b; Francis et al., 2013).

Since conservatism is so much a part of accounting standards and the resulting

financial reporting, many have attempted to measure the level of conservatism

employed by firms. Generally, conservatism is measured using one of three methods:

net assets, earnings and accrual methods, and earnings related to stock returns. Net

asset models attempt to measure the extent that assets are undervalued due to the

application of conservatism (Watts, 2003b). Earnings measures generally hold that

losses are more likely to reverse in future periods than gains (Watts, 2003b; Jackson

and Liu, 2010). The measures attempt to estimate the lag in this reversal. Accrual

methodologies attempt to measure negative accruals over a long period of time (Givoly

and Hayn 2002). Stock return methodology starts with the assumption that losses are

typically reflected in the stock price during the same period reported. However, gains

are recognized in stock prices earlier than they are ultimately reported through financial

statements (Basu, 1997).

The overwhelmingly most widely used measure of conservatism is Basu’s (1997)

asymmetric timeliness of earnings measure (AT) (Wang, et.al., 2009). Asymmetric

timeliness means that, due to conservatism, earnings reflect bad news quicker than

good news (Basu,1997). The regression estimates a slope coefficient on how timely

stock return is recognized in earnings based on the type of news utilizing the dummy

variable to distinguish between the news (Basu, 1997). As the most often cited

measure of conservatism, the Basu regression obviously has strengths (Wang, et.al.,

2009). It has been widely used for over twenty years; many researchers utilizing the AT

measure have produced results that are consistent with their predictions increasing both

the confidence in the model and the theory; and the Basu regression works well with

large cross-sectional analysis (Ryan, 2006).

Another methodology used to measure conservatism is the market-to-book or book-to-

market ratio. This methodology utilizing the assumption that all other things being

equal, conservatism in accounting depresses the book value of a firm relative to the true

economic value of the firm (Givoly et.al., 2007). This general methodology is based on

the residual income valuation model whereby Feltham and Ohlson (1995) incorporated

accounting conservatism in a valuation context (Givoly et.al., 2007). Beaver and Ryan

Accountancy Business and the Public Interest 2021

59

(2000) later developed a model utilizing six years of lagged stock returns in a panel data

regression.

Givoly and Hayn’s (2000) negative accrual measure uses non-operating accruals as a

subset of book value. By deferring gains and accelerating recognition of losses, this

model measures the general increase in conservatism over time (Givoly and Hayn,

2000). A similar methodology is the hidden reserve (or cookie jars) method developed

by Penman and Xiao-Jun (2002). Their model creates a C score that consists of the

estimated hidden reserve divided by the net operating assets of the firm (operating

assets minus operating liabilities, excluding financing liabilities). Givoly et al., (2007)

point out that the estimated reserve method involves a lot of estimation to derive

another estimation. It is also apparent the model does not apply to firms who do not

utilize LIFO but may have significant lower of cost or market adjustments in their

inventory. The model also does not take into consideration any other potential “cookie

jars” such as the allowance for doubtful accounts and inventory obsolescence.

The Basu regression, AACF, market-to-book ratio, negative accrual measure, and C

Score utilize aggregate accounting measures and end up with the conclusion that

accounting is conservative and has become more conservative over time (Watts,

2003a). Jackson and Liu (2010) were the first to assess conservatism on an individual

accrual account, the allowance for doubtful accounts. In their study of firms from 1980

through 2004, they developed two measures of conservatism related to the allowance

for doubtful accounts (Jackson and Liu, 2010). Their study finds that between 1980 and

2004 the average firm had amounts in its allowance for doubtful accounts enough to

cover two and a half years of write-offs.

Their measures only look at the allowance as it relates to the income statement rather

than also reviewing the balance sheet impact. Although they did report an average of

the allowance account as a percentage of the total accounts receivable, they did not

comment on the conservative nature of the ratio.

Hypotheses

As Jackson and Liu (2010) and others have indicated, excessive conservatism can be

prevalent because auditors view overstatement of assets or understatement of liabilities

as a higher risk than understatement of assets or overstatement of liabilities (Arens et

al., 2012). There is evidence in numerous studies that indicates auditors are permissive

on the overstatement of the allowance for doubtful accounts and resulting

understatement of net accounts receivable (Francis and Krishnan, 1999; Kinney and

Martin, 1994; Nelson et al., 2002). In fact, Nelson et al. (2002) find that auditors only

adjust for overstated liabilities approximately 37% of the time. Jackson and Liu (2010)

found that the allowance for doubtful accounts was conservative in a study of

companies from 1980 through 2004. Therefore, hypothesis one is as follows:

H1: The allowance for doubtful accounts is overstated by chemical and allied

products manufacturers.

Accountancy Business and the Public Interest 2021

60

Repeated application of unconditional conservatism can create hidden reserves that

can be released into income that distorts reported performance (Penman and Xiao-Jun,

2002). Jackson and Liu’s (2010) illustration in Table 1, below, provides a vivid

illustration of how these hidden reserves can build over time like the following:

Table 1 – Build-up of Cookie Jar Reserves in Allowance for Doubtful Accounts

This illustrates a company that is likely simply recording bad debt expense of $1,000 per

year and only writing off $900 per year. In short time, the allowance account represents

2.2 years’ worth of bad debts, or net accounts receivable is now understated by $1,100.

Jackson and Liu (2010) found that on average firms had about 3.2 years’ worth of bad

debt in their allowance for doubtful accounts. Others have observed that in general

conservatism has increased in accounting over the years (Watts, 2003a; Givoly and

Hayn, 2000). Therefore, hypothesis two is as follows:

H2: Chemical and allied products manufacturers have increasingly overstated

their allowance for doubtful accounts since 2004.

Data and Methodology

A temporal analysis of bad debt expense has been performed. H1 and H2 are both

measures of the size of the allowance for doubtful accounts as they would relate to

reasonableness and consistency. Therefore, they are tested with the following:

CON_1 = ALLOW

it

/WO

it+1

CON_2 = BDE

it

– WO

it+1

ALLOW is the allowance for uncollectible accounts. WO is write-offs of uncollectible

accounts. BDE is bad debt expense. i and t are firm and year subscripts.

In auditing these would be described as analytical procedures (Arens et al., 2012). An

analytical procedure is designed to allow an auditor to estimate what the dollar amount

Beginning Ending

Allowance Bad Allowance

for Doubtful Debt for Doubtful

Year

Accounts Expense Write-offs Accounts

1 - 1,000 - 1,000

2 1,000 1,000 900 1,100

3 1,100 1,000 900 1,200

4 1,200 1,000 900 1,300

5 1,300 1,000 900 1,400

6 1,400 1,000 900 1,500

7 1,500 1,000 900 1,600

8 1,600 1,000 900 1,700

9 1,700 1,000 900 1,800

10 1,800 1,000 900 1,900

11 1,900 1,000 900 2,000

Accountancy Business and the Public Interest 2021

61

of an account should be or set an expectation (Arens et al., 2012). The expected value

of CON 1 is one. The allowance account should represent the amount of bad debt in

accounts receivable that will not be collected. Since forms 10K do not indicate which

sales year a write-off relates to, all the write-offs in year t+1 will be assumed to be from

year t. A value of greater than one indicates the allowance for doubtful accounts is

overstated. Similarly, the expected values of CON 2 is zero because the bad debt

expense for period t is expected to equal the write-offs for period t+1. Values higher

than these would indicate the allowance account is overstated.

We further test these assertions by empirically temporally examining the yearly medians

for CON_1 and CON_2 over the years of this study (YR). This research assigns

numbers for each year that increase sequentially over the 2005 to 2017 years where

year 2005 is equal to 0 and 2017 is equal to 11.

That is:

ALLOW

it

/WO

it+1

= YR

BDE

it

– WO

it+1

= YR

A positive sign on the YR coefficients would provide support for the notion that firms

have increasingly overstated their allowance accounts.

Traditionally, the allowance for doubtful accounts has been viewed as unconditional

conservatism (Ruch and Taylor, 2015). However, unconditional conservatism is based

on information known at the beginning of an asset’s life while conditional conservatism

is based on information obtained future periods (Basu, 2005). Changes in the

methodology for determining bad debt expense based on current conditions rather than

consistently applied processes would indicate that the allowance for doubtful accounts

is conditional conservatism.

In gathering the data, this study obtained total accounts receivable, total allowance for

uncollectible accounts, total assets and other firm-level data from COMPUSTAT

database of North American firms for companies with the standardized industry code

(SIC) of 28 which represents chemical and allied products manufacturers. Bad debt

expense and write-offs are not reported by COMPUSTAT, so they were obtained from

the firms’ forms 10K schedule II filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission

(SEC) during the study period from 2005 (the period after the Jackson and Liu (2010)

research) through 2017.

The initial extraction from COMPUSTAT of firms with the SIC of 28 from 2005 through

2017 with accounts receivable balances and allowance for doubtful accounts resulted in

285 firms and 4,128 total observations. Utilizing Stata, the firm ID (gvkey) variable was

destrung into a numerical variable - gvkeynum. The resulting companies were sorted

by gvkeynum and fiscal year. Included in these companies were foreign registered

firms that do not report a Schedule II (or equivalent) for disclosures in changes of

valuation accounts. These were dropped for lack of data needed for the study. Also

dropped were all firms that did not have an allowance for doubtful accounts. Finally, the

EDGAR database was searched and Forms 10K were reviewed for bad debt expense

Accountancy Business and the Public Interest 2021

62

(BDE) and net write-offs (WO) for each firm year. Those firms that did not disclose

these changes in their allowance for doubtful accounts, typically citing immateriality,

were also dropped. The resulting sample was 88 total firms representing 795 firm

years. Of the 88 firms, 30 had data for the entire period from 2005 through 2017.

The manual entries of BDE and WO were reviewed to reduce researcher error by a

research assistant reading the amounts back to the researcher for confirmation with the

10K. Subsequent verification of amounts by starting with the beginning of the year

allowance for doubtful accounts adding bad debt expense and then subtracting net

recoveries, as has been referenced in earlier research (Jackson and Liu, 2010), is

impossible because virtually 100 percent of the companies have other activity in the

allowance for doubtful accounts such as acquisitions, divestitures and most commonly

foreign currency changes. In addition, prior research has indicated the use of gross

write-offs and gross recoveries in modeling (Jackson and Liu, 2010). Again, this was

not possible. Substantially all companies reported net write-offs or recoveries.

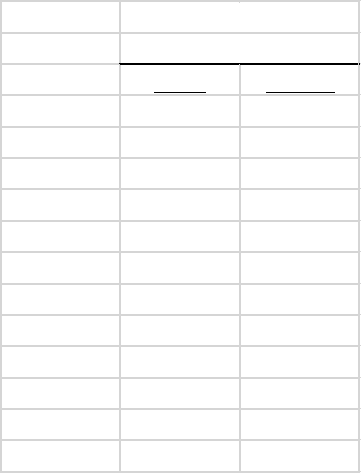

Table 2 – Summary Statistics for Sample

Results

H1 states that the allowance for doubtful accounts is overstated by companies, and H2

states that the level of overstatement is increasing. These are tested by CON_1 and

CON_2.

As noted above, CON_1 = ALLOW

it

/WO

it+1

. Therefore, a zero value in WO

it+1

results in

an irrational number that cannot be analyzed. However, zero write-offs in companies

that are recording bad debt expense could be a significant factor in measuring whether

the allowance for doubtful accounts is overstated. Therefore, the researcher added

.001 to all write-offs to eliminate zero write-offs. This did not modify any write-offs that

were originally negative (net recoveries) or existing write-offs. However, it created

values for the years where companies had zero write-offs. Both BDE and WO were

winsorized at the 1

st

and 99

th

percentile levels utilizing Stata. The resulting data

modifications had significant outliers due to extremely low write-offs creating extremely

high means per year in CON_1. The overall mean for the 12 years was 1,263.10 and

standard deviation of 377.34. The minimum value was 691.09 for 2006, and the

maximum value was 1,817.32 for 2011. To put this in perspective, replacing zero write-

Total Observations: 795

Standard

Mean

Deviation Minimum Maximum

Total assets (millions) 9,356 18,395 38 192,164

Sales (Millions) 6,234 10,532 5 71,312

Market value (Millions) 13,949 28,557 0 258,341

Accounts receivable to total assets 0.91% 2.0% 0.0% 13.9%

Accounts receivable to current assets 2.36% 4.9% 0.0% 34.5%

Bad debt expense to net income 1.10% 165.2% 4345.5% 1009.1%

Write-offs to net income 1.18% 173.0% 4436.4% 1100.0%

Accountancy Business and the Public Interest 2021

63

offs results in an average of 1,263 years of write-offs reserved by the allowance for

doubtful accounts. Given the wide variation of the means, the medians are believed to

be a better test.

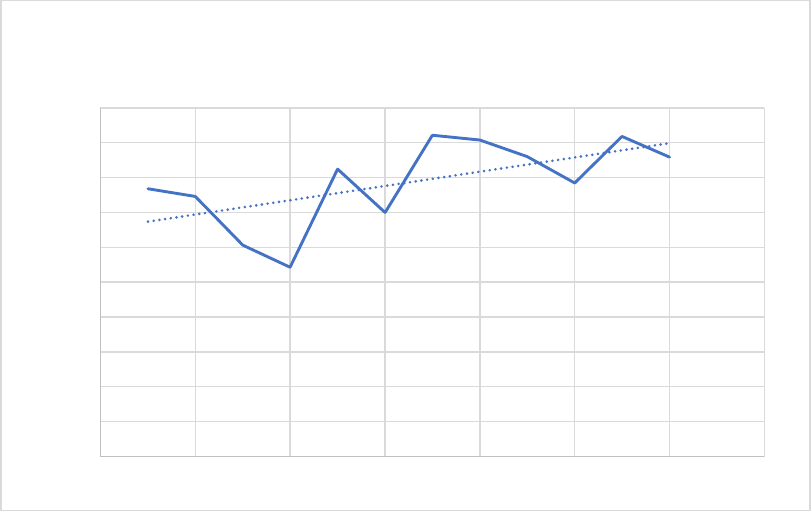

While the means result in extremely high values for CON_1 the medians during the

study period result in more reasonable values. The medians range from a low of 2.714

in 2008 to a high of 4.606 in 2011. As Table 3 indicates, the trend is increasing for the

entire study period.

Table 3 – CON_1 Medians Replacing Zeros with .01

Jackson and Liu (2010) found on average companies had 3.031 years’ worth of write-

offs (CON_1) in 2004. They haphazardly utilized 5.5 years for missing write-offs.

Based on their findings and the significant outliers causing very unusual calculations for

CON_1 means, missing CON_1 values due to zero write-offs were re-keyed as 3.031.

Also, negative CON_1 values due to net recoveries were re-keyed as 3.031 as well.

This treatment ignores the impact of a few companies with zero write-offs in specific

years and, in some instances, companies with zero write-offs during the entire research

period. Therefore, the actual results would be higher CON_1 amounts if an estimate of

CON_1 for these companies could be obtained. The median for resulted in 3.031 for

each period, so this methodology was rejected. The researcher believes utilizing the

medians where zeros are replaced with .01 provides the best information for reaching

conclusions.

A reasonable value for CON_1 would be one, as this would assume that 100% of next

year’s write-offs are “reserved” by this year’s allowance for doubtful account. However,

even a value of one could be an overstatement in the allowance for doubtful accounts.

-

0.500

1.000

1.500

2.000

2.500

3.000

3.500

4.000

4.500

5.000

2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 2014 2016 2018

CON_1 Median with

Zeros replaced with .01

Accountancy Business and the Public Interest 2021

64

Most firms have an accounts receivable turnover ratio of significantly higher than one

which means 100 percent of the dollar value of accounts receivables are collected more

often than once a year. Table 4 presents summaries of the sample companies’

accounts receivable turnover rations for the study period.

Table 4 – Accounts Receivable Turnover Ratios

In every year the sample companies’ average accounts receivable turnover ratio is

significantly higher than one which leads to the conclusion that a reasonable value for

CON_1 should be less than one. Never-the-less, the researcher will consider a CON_1

value of one as reasonable even though it is conservative or marginally overstated. As

noted earlier, Jackson and Liu (2010) observed a mean of 3.031 across all industries in

2004. This means for the year prior to this study, on average companies recorded an

allowance of over three times the next year’s write-offs.

As Table 3 shows, the median of CON_1 with zeros replaced with .01. The medians

ranged 1.892 with a low of 2.714 in 2008 to a high of 4.606 in 2011. The overall mean

of the medians during the study period was 3.810.

CON_1 values greater than one for the entire 795 firm years was 742 or 92.9 percent of

all observations with the overall mean for values greater than one of 7.585.

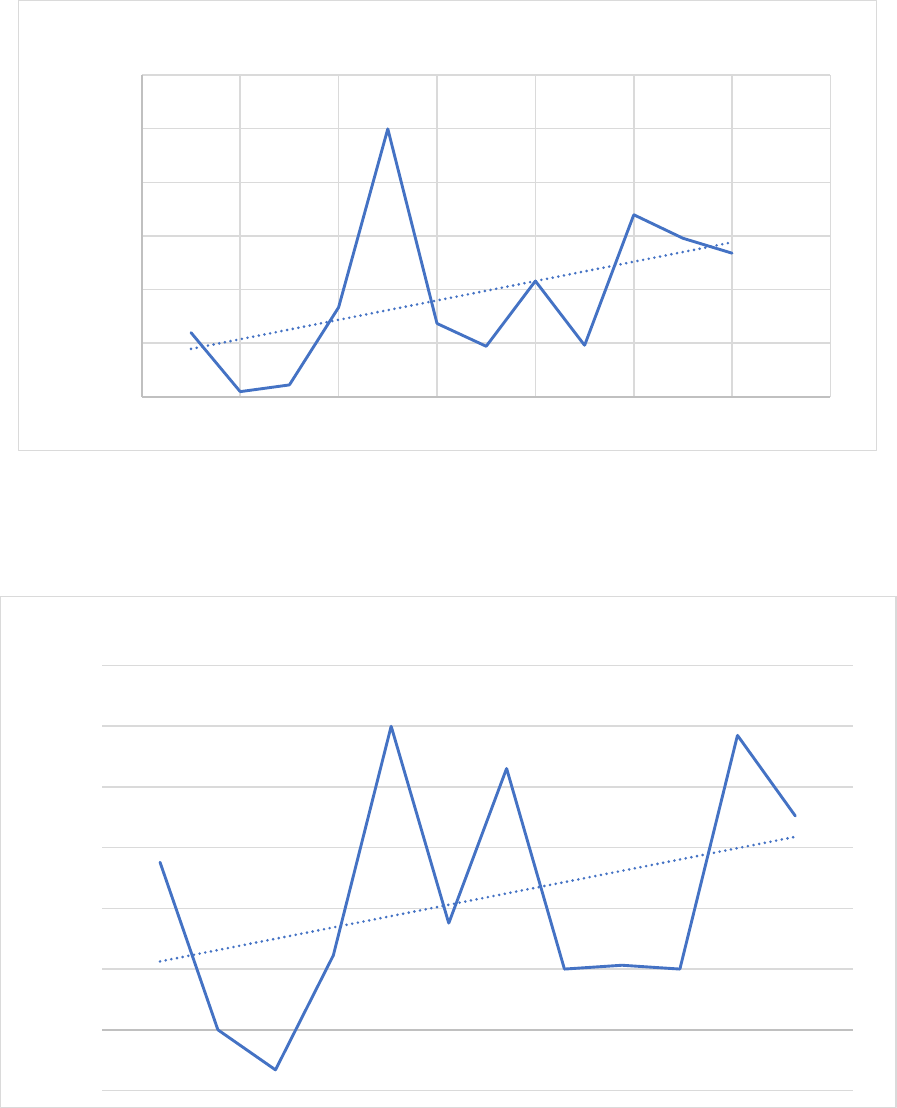

CON_2 is also a measure of overstatement of the allowance for doubtful accounts. As

noted above, CON_2 = BDE

it

– WO

it+1

. The expectation is that CON_2 will zero or even

less than zero is reasonable because the current year’s bad debt expense should

approximate the next year’s write-offs. During the study period, CON_2 ranged from a

low of .1905 in 2006 to a high of 9.995 in 2009. The overall mean was 3.899 with a

ninety-five percent confidence level of 1.984 for the period and a standard deviation of

2.95. Again, the trend for the study period is for CON_2 to increase.

Mean

Median

2005 N/A

N/A

2006 8.32

6.77

2007

7.42

6.54

2008

7.69

6.95

2009 7.58

6.40

2010 7.31

6.42

2011

9.16

6.71

2012

8.60

6.37

2013

7.76

6.25

2014 7.88

6.35

2015

7.75

5.99

2016 6.38

5.94

Turnover Ratio

Accounts Receivable

Accountancy Business and the Public Interest 2021

65

Table 5 – CON_2 Means

The median for CON_2 behaves in a similar manner with a minimum of (.132) and a

maximum of 1.0. The overall trend of the medians for the companies in the study period

is for CON_2 to increase.

Table 6 – CON_2 Medians

Similar to CON_1, where most firms exceed 1.0, the majority of firms have a CON_2

exceeding zero. However, the percentages do not match exactly and are generally

lower. Overall, 58.23 percent of the firms had CON_2 greater than zero during the

-

2.0000

4.0000

6.0000

8.0000

10.0000

12.0000

2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 2014 2016 2018

CON_2 Mean

(0.200)

-

0.200

0.400

0.600

0.800

1.000

1.200

2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017

CON_2 MEDIANS

Accountancy Business and the Public Interest 2021

66

study period. Table 7 summarizes CON_1 and CON_2 where their respective

thresholds are exceeded.

Table 7 – Percentage of Companies Exceeding CON_1 and CON_2 Thresholds

H1 and H2 are further tested by empirically, temporally examining the yearly medians

for CON_1 and CON_2 over the years of this study (YR). Numbers are assigned for

each year that increase sequentially over the 2005 to 2017 where year 2005 is equal to

0 and 2017 is equal to 11 as follows:

ALLOW

it

/WO

it+1

= YR

BDE

it

– WO

it+1

= YR

A positive sign on the YR coefficients would provide support for the notion that firms

have increasingly overstated their allowance accounts.

CON_1 CON_2

Year

> 1

> 0

2005 96.77% 62.90%

2006 90.48% 49.21%

2007 92.31% 44.61%

2008 93.55% 51.61%

2009 93.85% 73.85%

2010 92.19% 56.25%

2011 88.14% 54.24%

2012 95.38% 56.92%

2013 95.16% 56.45%

2014 95.24% 57.14%

2015 91.53% 69.49%

2016 90.57%

66.04%

Mean 92.93% 58.23%

Min 88.14% 44.61%

Max 96.77% 73.85%

Accountancy Business and the Public Interest 2021

67

Table 8 – YR independent variable of interest Median CON_1 and CON_2

Results show support the prior graphical depictions of CON_1 and CON_2 annual

medians. For both equations, the coefficients on the YR independent variables of

interest are positive and significant at the p < .001 levels.

Conclusions

Hypotheses 1

The first hypothesis is the allowance for doubtful accounts is overstated by chemical

and allied products manufacturers. This hypothesis was first tested using the

calculation of the allowance for doubtful accounts divided by the next year’s write-offs of

accounts receivable, or CON_1. As previously discussed, a value of one would be

reasonable and still conservative. However, realistically, a value less than one would

still be reasonable because during the study period from 2005 through 2016, the

median accounts receivable turnover ratio ranged between 5.9 and 7.0 for the industry.

This means that companies will collect their entire balance of accounts receivables

approximately six time each year, so a CON_1 of one is still probably an overstatement

of the allowance for doubtful accounts. The median for CON_1 over the entire study

period was 3.92. The mean, due to several companies having zero write-offs, was a

huge at 1,263 when zero write-offs were replaced with .01. As Panel 1 shows, the

median of CON_1 ranged from a low of 2.714 in 2008 to a high of 4.606 in 2011. The

overall mean of the medians during the study period was 3.810. Approximately 93

percent of the sample companies had a CON_1 greater than one during the study

period.

The first hypothesis also was tested with the calculation of simply bad debt expense

less next year’s write off, or CON_2. A value of zero or even less would be reasonable.

The results show the mean for CON_2 during the study period ranged from 0.190 to

9.99 with an overall mean of 3.90. Approximately 58 percent of the sample companies

had a CON_2 of greater than zero during the study period.

Based on the results of analyzing CON_1 and CON_2, the null hypothesis is rejected.

The researchers conclude that the allowance for doubtful accounts is overstated by

chemical and allied products manufacturers during the study period of 2005 through

2016.

Standard

Median

Con_1 Coefficient

Error

t - value

p-value

YR 0.0111061 0.001716 6.47 0.000 0.007738 0.014475

Cons 2.890669 0.0148743 194.34 0.000 2.861472 2.919867

Median Con_2

YR 0.104492 0.0058813 17.08 0.000 0.088904 0.111994

Cons -0.264876 0.0509789 -5.20 0.000 -0.364945 -0.164806

95% Confidence Interval

Accountancy Business and the Public Interest 2021

68

Hypothesis 2

The second hypothesis is chemical and allied products manufacturers have increasingly

overstated their allowance for doubtful accounts since 2004. This too was tested using

CON_1 and CON_2 as described above. The researcher, utilizing Excel’s graphing

features, inserted a trend line into each of the line graphs of the means and medians of

CON_1 and CON_2. As illustrated in the graphs of CON_1 and CON_2, shown on

Panels one, two and three, each have a positive trend line in both the means and the

medians. This assertion was further tested by empirically temporally examining the

yearly medians for CON_1 and CON_2 over the years of this study (YR). Results of

those regressions support the graphical depictions of CON_1 and CON_2.

Based on these results, the null hypothesis is rejected, and the conclusion is chemical

and allied products manufacturers have increasingly overstated their allowance for

doubtful accounts since 2004.

Opportunities for Future Research

Since the study is in only one industry, additional research into other industries should

be completed to determine to what extent results can be generalized.

Other valuation accounts, such as those for inventory and taxes, are also required by

generally accepted accounting principles. These accounts could be subject to

manipulation by management and are worthy of study. As is the case with the

allowance for doubtful accounts, both the inventory reserve account and the income tax

valuation account require disclosure of activity in Schedule II. Inventory valuation

reserves would change in a manner like the allowance for doubtful accounts. The

current period’s reserve should be realized as losses in the next period. Therefore, the

methodology utilized in this study could be modified to test inventory valuations in

companies with significant inventories.

Income tax valuation accounts could have more than one year before the ultimate

realization of losses in deferred tax assets. Therefore, the methodology for testing

would require expansion to multiple years depending on the nature of the underlying tax

assets. However, the information for deferred tax assets and their ultimate realization is

disclosed in the footnotes to the financial statements.

While there is strong inference that the allowance for doubtful accounts represents

conditional rather than unconditional conservatism, this study does not directly test the

classification. Therefore, addition research designed to specifically test the

classification of bad debt expense could be performed.

Additional research is also available for the reasoning why companies have overstated

their allowance for doubtful accounts. Do companies utilize their cookie jar reserves in

the allowance for doubtful accounts to manipulate earnings?

Accountancy Business and the Public Interest 2021

69

References

Ahmed, A. & Duellman, S. (2007). Accounting conservatism and board of director

characteristics: An empirical analysis. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 43,

411–437.

Ahmed, A., Billings, B., Morton, R., & Stanford-Harris, M. (2002). The role of accounting

conservatism in mitigating bondholder-shareholder conflicts over dividend policy

and in reducing debt costs. The Accounting Review, 77, 867–890.

Arens, A., Elder, R, Beasley, M. (2012). Auditing and Assurance Services: An

Integrated Approach, 14

th

Edition. Boston, MA: Pearson.

Balachandran, S. & Mohanram, P. (2011). Is the decline in the value relevance of

accounting driven by increased conservatism? Review of Accounting

Studies, 16(2), 272-301.

Ball, R. and L. Shivakumar. (2005). “Earnings Quality in UK Private Firms: Comparative

Loss Recognition Timeliness.” Journal of Accounting and Economics 39, 83-128.

Basu, S. (1997). The conservatism principle and the asymmetric timeliness of earnings.

Journal of Accounting and Economics, 24, 3–37.

Basu, S. (2005). Discussion of "Conditional and Unconditional Conservatism: Concepts

and modeling". Review of Accounting Studies, 10(2-3), 311-321.

Beaver, W. & Ryan, S. (2000). Biases and lags in book value and their effects on the

Book-to-Market ratio to predict book return on equity. Journal of Accounting

Research, 38(1), 127-148.

Beneish, M.D. & Press, E. (1993). Costs of technical violation of accounting-based debt

covenants. The Accounting Review, 68 (April), 233-257.

Bliss, J.H. (1924). Management through the accounts. New York, NY: The Ronald

Press.

Boockholdt, J. L. (1978). Influence of Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century Railroad

Accounting on Development of Modern Accounting Theory. The Accounting

Historians Journal 5(1), 9–28.

Caylor, M. (2010). Strategic Revenue Recognition to Achieve Earnings Benchmarks.

Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 29, 82-95.

Davis, H.Z. (1982). History of LIFO, The Accounting Historians Journal 9(1), 1-23.

Feltham, G. & Ohlson, J. (1995). Valuation and clean surplus accounting for operating

and financing activities. Contemporary Accounting Research, 11(2), 689-731.

Accountancy Business and the Public Interest 2021

70

Financial Accounting Foundation. (2017a), ASC 360-10-35-21 “Property Plant and

Equipment-Overall Subsequent Measurement- Impairment or Disposal of Long

Lived Assets.”

Financial Accounting Foundation. (2017b), ASC 330-10-35-1 “Inventory-Overall

Subsequent Measurement- Adjustments to Lower of Cost or Market.”

Financial Accounting Foundation. (2017c), ASC 450-20-25-1 and 2 “Contingencies-Loss

Contingencies—Recognition-General Rule.”

Financial Accounting Foundation. (2017d), ASC 450-30-25-1 and 2 “Contingencies-

Gain Contingencies—Recognition-General.”

Financial Accounting Foundation. (2017e), ASC 310-10-05 “Receivables in General”

Financial Accounting Standards Board. (1980). Concepts Statement No. 2: Qualitative

Characteristics of Accounting Information. Norwalk: Financial Accounting

Standards Board.

Financial Accounting Standards Board. (2010). Concepts Statement No. 8: Chapter 1,

The Objective of General Purpose Financial Reporting, and Chapter 3,

Qualitative Characteristics of Useful Financial Information. Norwalk: Financial

Accounting Standards Board.

Francis, B., Hasan, I., & Wu, Q. (2013). The benefits of conservative accounting to

shareholders: Evidence from the financial crisis. Accounting Horizons, 27(2),

319.

Francis, J., Krishnan, J. (1999). Accounting Accruals and Auditor Reporting

Conservatism. Contemporary Accounting Research, 16, 135-165.

Givoly, D. and Hayn, C. (2000). The changing time-series properties of earnings, cash

flows and accruals: Has financial accounting become more conservative?

Journal of Accounting and Economics, 29(3), 287-320.

Givoly, D. and Hayn, C. (2002). Rising Conservatism: Implications for Financial

Analysis. Financial Analysts Journal, 58(1), 56-74.

Givoly, D., Hayn, C., & Natarajan, A. (2007). Measuring reporting conservatism.

Accounting Review, 82(1), 65-106.

Gordon, E.A., Raedy, J.S., & Sannela, A.J. (2016). Intermediate Accounting. Boston,

MA: Pearson.

Houmes, R. & Skantz, T. (2010). Highly Valued Equity and Discretionary Accruals.

Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 37(1), 60-92.

Ivashina, V., and Scharfstein, D. (2010). Bank lending during the financial crisis of 2008.

Journal of Financial Economics, 97, 319–338.

Accountancy Business and the Public Interest 2021

71

Jackson, S. B., & Liu, X. (. (2010). The allowance for uncollectible accounts,

conservatism, and earnings management. Journal of Accounting

Research, 48(3), 565-601.

Kinney, W. & Martin, R. (1994). Does Auditing Reduce Bias in Financial Reporting? A

Review of Audit-Related Adjustment Studies. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and

Theory, 13, 149-156.

LaFond, R. & Watts, R. (2008). The informational role of conservatism. The Accounting

Review, 83, 447-478.

Leftwich, R. (1995). The Agenda of the Financial Accounting Standards Board. Working

paper, University of Chicago.

Marquardt, C., Wiedman, C. (2004). How are Earnings Managed? An Examination of

Specific Accruals. Contemporary Accounting Research, 21, 461-491.

McNichols, M., & Wilson, G. P. (1988). Evidence of earnings management from the

provision for bad debts; discussion. Journal of Accounting Research, 26, 1.

Nelson, M., Elliott, J. & Tarpley, R. (2002). Evidence from Auditors about Managers’ and

Auditors’ Earnings Management Decisions. The Accounting Review, 77, 175-

202.

Pendorf, B., 1930. The Relation of Taxation to the History of the Balance Sheet. The

Accounting Review, 5(3), 243-251.

Penman, S., & Xiao-Jun, Z. (2002). Accounting conservatism, the quality of earnings,

and stock returns. The Accounting Review, 77(2), 237-264.

Ruch, G. W., & Taylor, G. (2015). Accounting conservatism: A review of the

literature. Journal of Accounting Literature, 34, 17-38.

Ryan, S. (2006). Identifying conditional conservatism. European Accounting Review,

15(4), 511-525.

Sailers, E.A. (1939). Depreciation: Principles and Applications. 3

rd

Edition. New York.

Ronald Press.

Skinner, D.J. (1994). Why Firms Voluntarily Disclose Bad News. Journal of Accounting

Research, 32, 53-99.

Smith, C.W. & Watts, R.L. (1982). Incentive and tax effects of executive compensation

plans. Australian Journal of Management, 7, 139-157.

Sterling, R. (1967). Conservatism: The fundamental principle of valuation in traditional

accounting. Abacus, 3(2), 109-132.

Teoh, S., Wong, T., Rao, G. (1998). Are Accruals during Initial Public Offerings

Opportunistic? Review of Accounting Studies, 3, 175-208.

Accountancy Business and the Public Interest 2021

72

Vance, L. (1943). The Authority of History in Inventory Valuation. The Accounting

Review, 18(3), 219-227. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/240765

Wang, R.Z, Ὸ hῸgartaigh, C. & van Zijl, T. (2009). Measures of Accounting

Conservatism: A Construct Validity Perspective. Journal of Accounting

Literature, 28, 165-203.

Watts, R. L. (2003a). Conservatism in Accounting Part I: Explanations and

Implications. Accounting Horizons, 17(3), 207-221.

Watts, R. L. (2003b). Conservatism in Accounting Part II: Evidence and Research

Opportunities. Accounting Horizons, 17(4), 287-301.

Watts, R. and Zimmerman, J. (1978). Towards a Positive Theory of the Determination of

Accounting Standards. The Accounting Review, 53, 113-134.

Watts, R. and Zimmerman, J. (1986). Positive accounting theory. Englewood Cliffs,

NJ: Prentice Hall.

Yao, H. & Deng,Y. (2018). Managerial incentives and accounts receivable

management policy. Managerial Finance, 44 (7), 865-884,

https://doi.org/10.1108/MF-05-2017-0148.

Zhang, J. (2008). The contracting benefits of accounting conservatism to lenders and

borrowers. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 45(1), 27-54.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2007.06.002