15 Measures of Dairy

Farm Competitiveness

2

15 Measures of Dairy Farm Competitiveness

Authors

Dianne Shoemaker

Maurice Eastridge

Bill Weiss

Jason Hartschuh

Chris Zoller

Rory Lewandowski

Debbie Brown

Glen Arnold

David Marrison

Chris Bruynis

Our objective is to support and promote a profitable, sustainable, and environmentally

sound

dair

y

ind

ust

r

y

in Ohio

thr

oug

h

unb

iase

d,

r

esear

c

h-b

ased education.

We encourage you to visit our web site for additional

i

n

f

o

r

m

a

t

i

o

n

a

n

d

l

i

n

k

s

t

o

O

h

i

o’

’

s

d

a

i

r

y

i

n

d

u

s

t

r

y

partners at http://dairy.osu.edu.

Dairy Excel is a multi-faceted management education program specifically designed to

improve the competitiveness of the Ohio dairy industry.

For a list of OSU Extension offices, go to:

https://extension.osu.edu/lao#county

This publication was originally printed October 1997;

Revised January 2008; and Revised January 2019

Authors of the original publication were: Jim Polson, Dianne Shoemaker, Ernie Oelker,

and Gary Schnitkey.

2008 Revision Authors: Dianne Shoemaker, Maurice Eastridge, Don Breece, Julia

Woodruff, Duane Rader, and David Marrison.

Copyright © 2019, The Ohio State University

CFAES provides research and related educational programs to clientele on a nondiscriminatory basis.

For more information, visit cfaesdiversity.osu.edu. For an accessible format of this publication, visit

cfaes.osu.edu/accessibility.

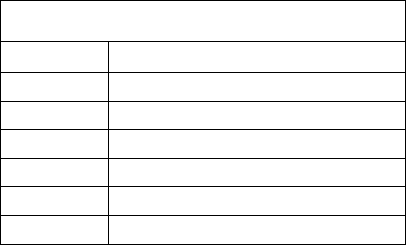

3

Introduction

4

Gaining Control of Your Business

7

The 15 Measures

10

Measure 1: Rate of Production — Pounds of Milk Sold Per Worker

12

Measure 2: Cost Control —Feed

14

Measure 3: Cost Control — Operating Expense Ratio

19

Measure 4: Capital Efficiency — Dairy Investment Per Cow

21

Measure 5: Capital Efficiency — Asset Turnover Ratio

23

Measure 6: Profitability — Net Farm Income Per Cow

25

Measure 7: Profitability — Rate of Return on Farm Assets

27

Measure 8: Liquidity — Current Ratio and Working Capital

29

Measure 9: Repayment Schedule — Scheduled Debt Payment

32

Measure 10: Solvency — Debt to Asset Ratio

34

Measure 11: Solvency — Debt Per Cow

36

Measure 12: Mission Statement

38

Measure 13: Maintain Family’s Standard of Living

40

Measure 14: Motivated Labor Force

42

Measure 15: Manure Nutrient Management

44

The Fork in the Road for Dairy Farms

48

References

52

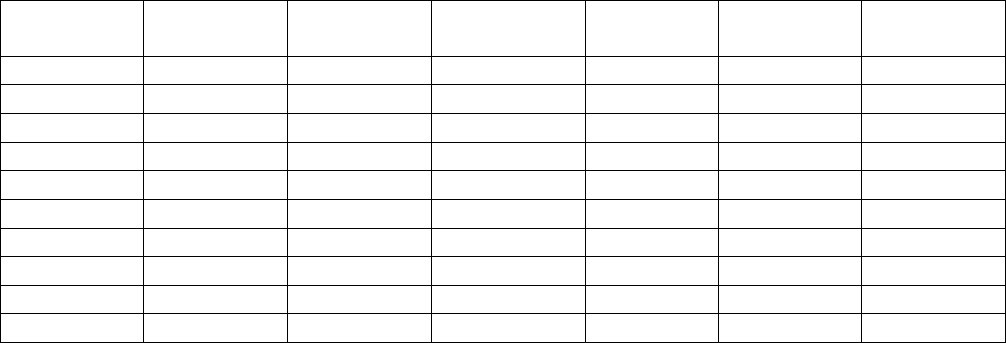

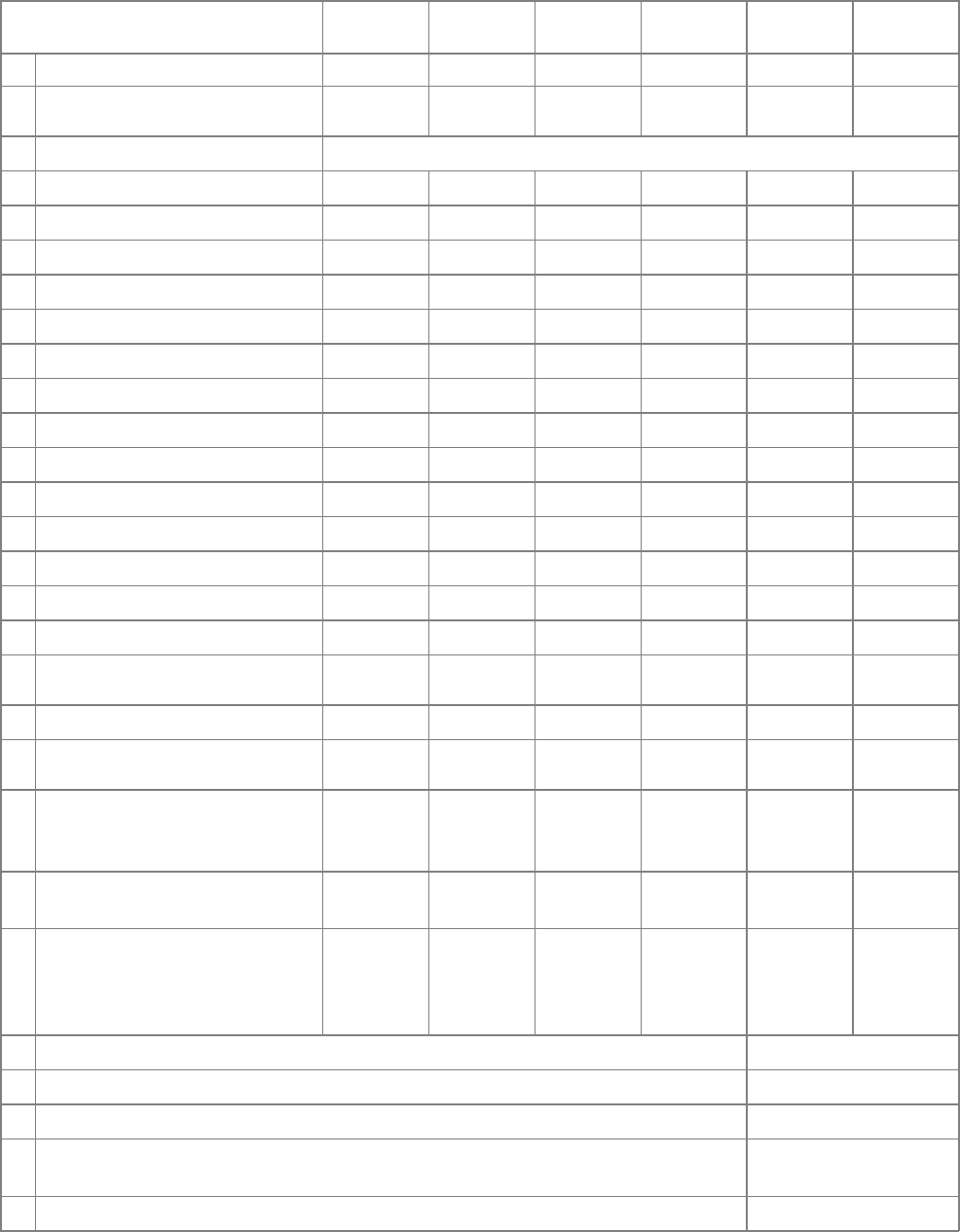

Appendix A: Feed Cost and Quantity Calculations

55

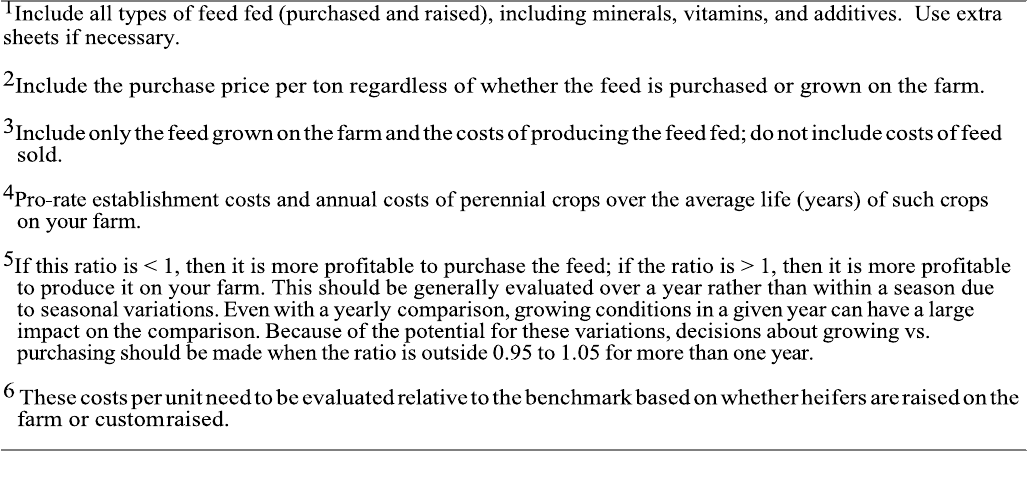

Appendix B: Projected Feed Costs Per Cwt of Milk Sold and Amount of Feed Needed for Dairy Cattle

58

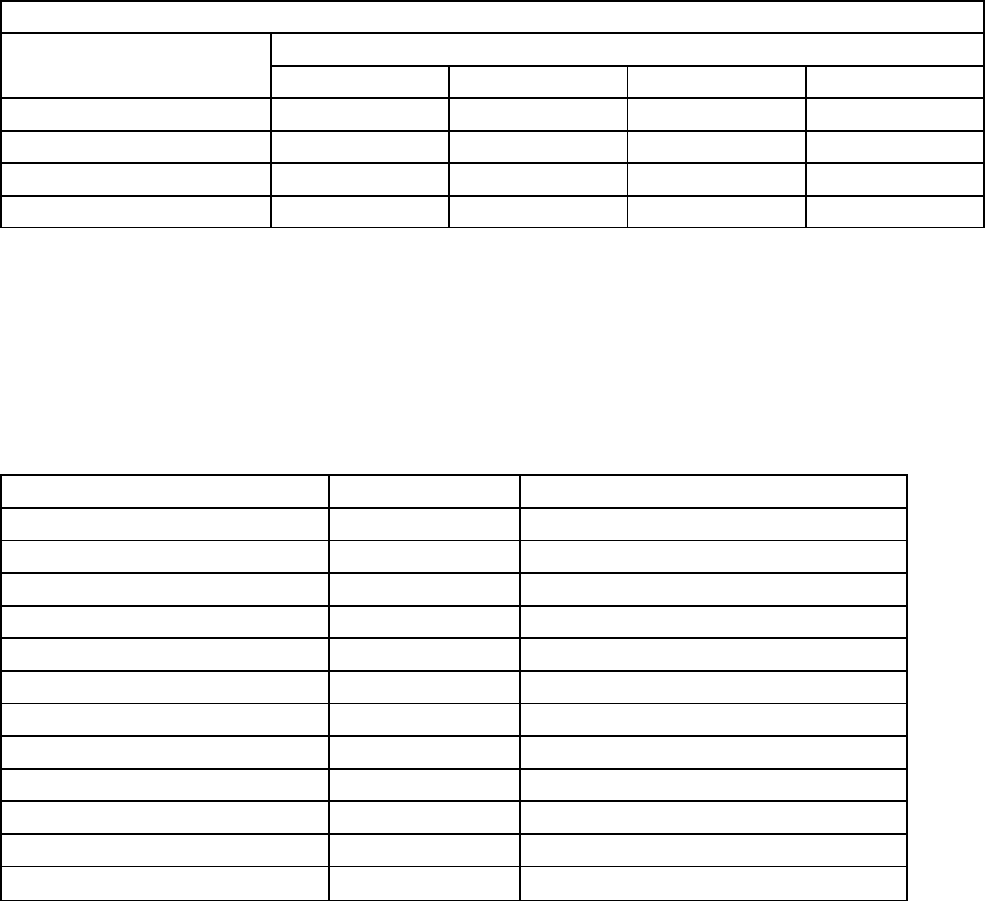

Appendix C: Conducting a SWOT Analysis of Your Agricultural Business

60

Appendix D: Mission Statement Worksheet

63

Appendix E: Planning for the Successful Transition of Your Agricultural Business

64

Content

4

Introduction

The 15 Measures represent key characteristics of

the most competitive dairy producers in the

Midwest. The most competitive dairy producers

already exceed many of the measures. While a

single dairy business often does not meet all 15

measures, dairy producers who meet the majority of

these measures should maintain long-term

competitiveness with dairy producers anywhere in

the world.

First published in 1997, the 15 Measures remain

strong indicators of profitable, sustainable dairy

businesses. As we reviewed and revised the

measures, some competitive levels were adjusted to

reflect current industry trends and realities. Overall,

the measures continue to represent strong indicators

of success in the dairy industry.

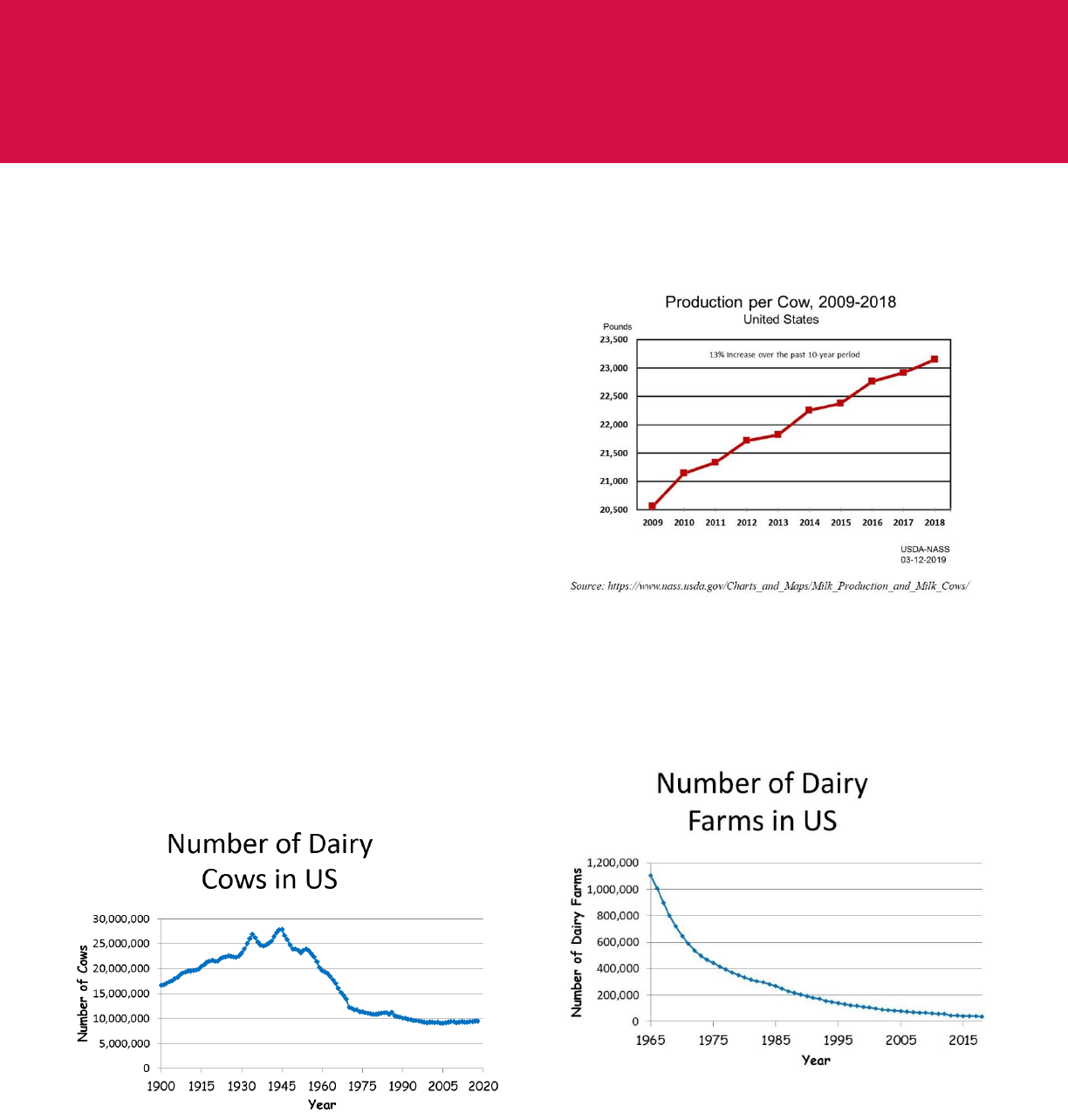

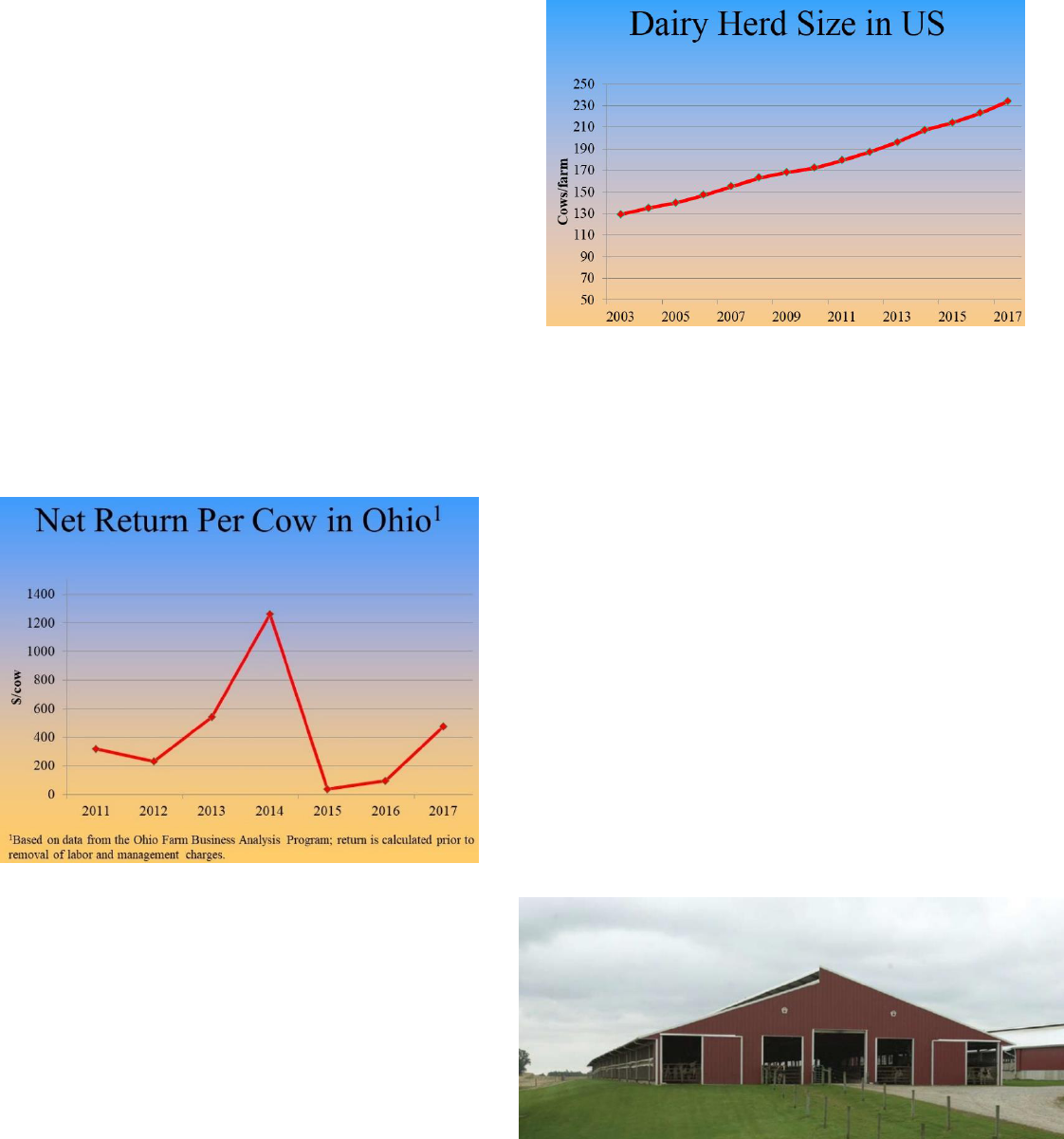

The dairy industry is very dynamic and global, with

continuing trends of fewer farms with more cows

per farm. This does not mean that a farm is

competitive just because it is growing in size. You

have to study a farm’s financials to know if it is

competitive.

Production per cow continues to increase due to a

variety of factors including improved genetics,

housing, feed quality and management practices.

Highly competitive farms use well-balanced rations

for the level of production in their herds while

utilizing competitively priced high quality

feedstuffs.

Some dairy businesses do not meet many of the

measures. Without change, these producers will

likely be exiting the dairy business within the next

few years. There has been a steady decline in the

number of dairy farms for over 50 years.

5

The 15 Measures fall into 11 broad areas which

provide a good overview of the competitiveness of a

dairy farm business. The 11 management areas are:

1. Rate of production

2. Cost control

3. Capital efficiency

4. Profitability

5. Liquidity

6. Repayment schedule

7. Solvency

8. Mission

9. Maintain family’s standard of living

10. Motivated labor force

11. Capturing dairy manure nutrients

Major problems in any one area can seriously limit

the ability of a dairy farm to compete. We selected

one or two measures in each management area as

indicators of how the farm is doing.

As a dairy farm manager, you should continuously

evaluate and analyze your farm from many

viewpoints. Farms performing well in some areas

may have serious weaknesses in others. Evaluating

your farm from several different perspectives as you

plan for the future ensures that your business is

structured and managed for competitiveness and

growth while managing your operation through a

volatile market. While the general projection is for a

positive dairy industry, historical trends show us

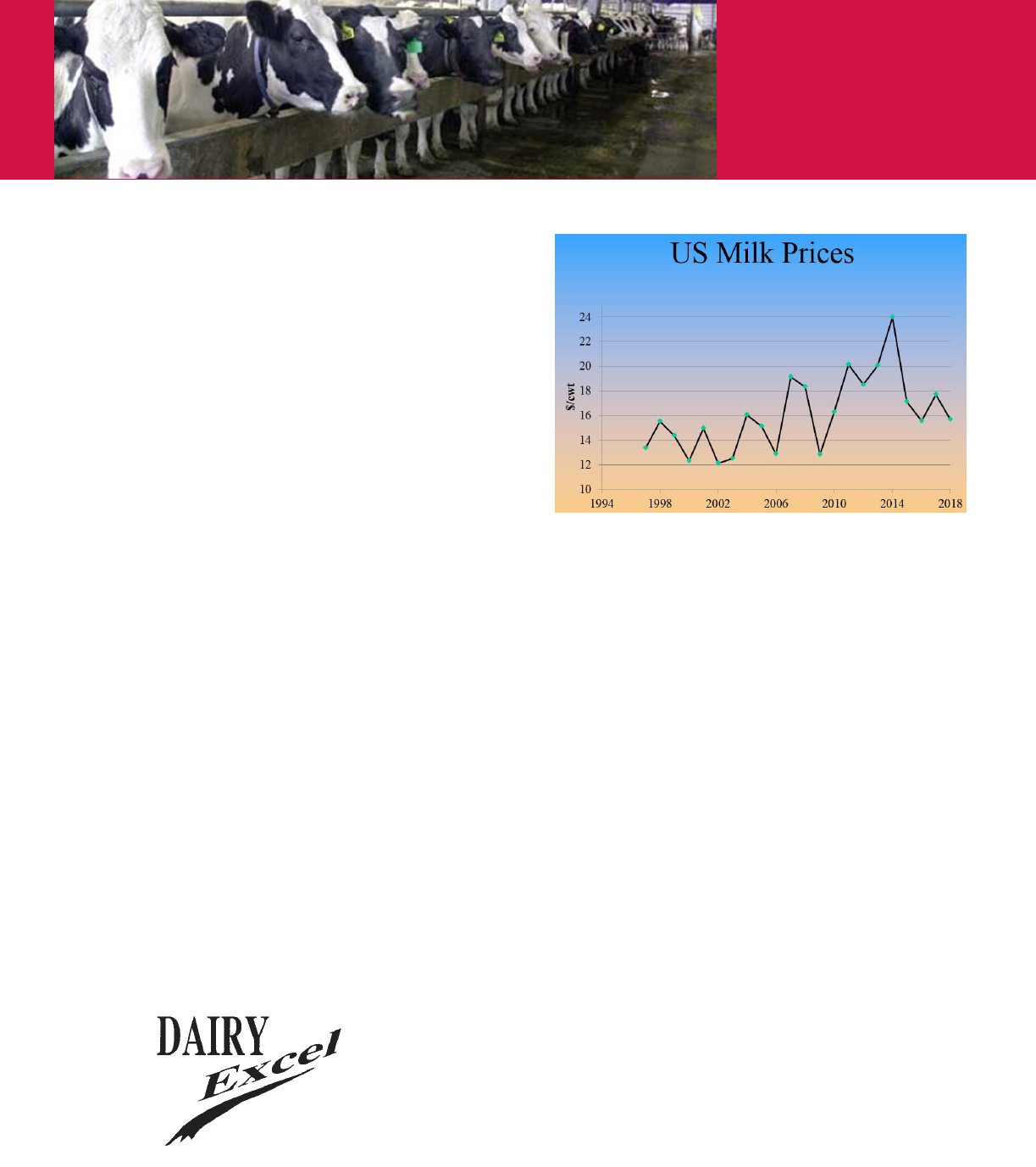

that market prices fluctuate greatly.

A summary of each measure is provided, along with

instructions for how to calculate, evaluate, and

interpret the measure, followed by a discussion

about the competitive range. We also suggest

changes to help a dairy operation move into the

competitive range.

Evaluating the profitability and sustainability of a

dairy farm business based on one or only a few

measures may result in an inaccurate or incomplete

assessment. All of the areas represented by the

measures are important for the long-term viability

of a business — and are related to and influenced by

each other. Look for those relationships in the

discussion of each measure.

Many dairy producers do not have the resources or

the desire to make the changes necessary to

compete with the most competitive farms on every

measure. Even when they have the desire, high debt

levels or limited resources make some of these

measures difficult for some dairy producers to

achieve. Producers who will not or cannot achieve

the desired ranges may continue to operate and

support a family for many years. However,

primarily because of inflation, those who do not

make changes to become or stay competitive in a

constantly changing industry can expect a declining

6

standard of living over time. These farms also run

the risk of using up any equity they have built in

their business and not being able to retire or pass the

business on to the next generation.

Because competitiveness requires a commitment to

constant improvement and change, these measures

will continue to change over time. Dairy producers

who want to stay competitive must continue to

improve, modernize, adapt, and change.

Being competitive is more than having the newest

technology. A dairy farm family with better-than-

average management must continuously increase its

gross farm income at the rate of inflation or greater

to maintain the family’s standard of living. Short-

and long-term decisions can greatly impact the

ability of a dairy business to grow in the future.

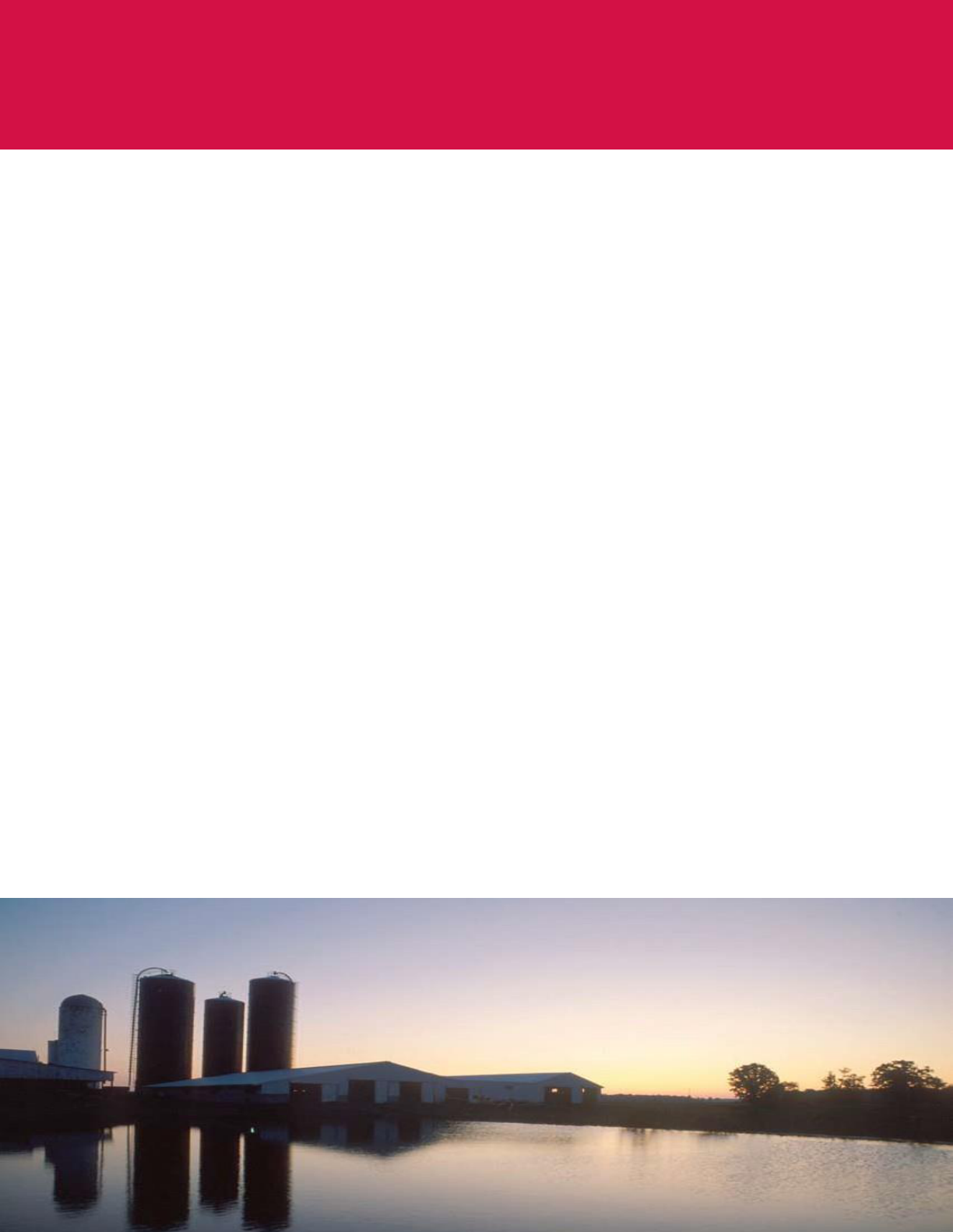

Dairy farm income per cow has gone up slightly

during the last 45 years, but the declining value of

the dollar (inflation) has dramatically reduced what

you can buy from the income of one cow.

Unfortunately, net returns per cow have fluctuated

dramatically in the last five years from over $1000

per cow to well below $200 per cow. Historically,

we have shown that a dairy farm manager needs to

increase cow numbers by 50% every 10 years just

to offset the impact of inflation. However, because

more cows means higher incomes and more income

tax, farmers must increase cow numbers at least

another 10% to pay the additional tax on the higher

income.

While the average US herd size has grown by 100

head in the last 14 years, increasing cow numbers

may not always be the best way to increase gross

farm income of which 5 to 10% is used for family

living.

Each farm, farm manager, and farm family is

different. At the end of this publication in the

section titled “The Fork in the Road for Dairy

Farms”, we offer suggestions to dairy farm

managers who:

1. Already are competitive

2. Want to become competitive

3. Would like to become competitive but

cannot, or

4. Do not want to become competitive

7

Gaining Control

of Your Business

Business managers gain and retain control

of their businesses one step at a time.

Thinking that you can quickly change or

improve all 15 areas at once is unrealistic.

Frequently, it takes many little changes and

perhaps several larger moves over months

and even years to make a major change in

a business. However, most dairy farmers

should compare their operation with all 15

of these measures at least once per year.

Farmers who want to maintain or grow

their operations long term must stay

competitive. These farms should strive to

be in the top third of dairy farms based on

net return per cow.

Provided next are four broad steps for

gaining control of your business:

Step 1: Set a Goal

The first step in gaining control of any part

of a business is to set a goal/target. In most

cases, one or more of our 15 Measures can

serve as a target. In most cases, a manager

will need to set a similar but slightly

different, more appropriate target for his or

her specific business. Thinking you can

quickly move to the level of the most

competitive dairy farms in the country is

unrealistic. However, setting goals higher

than current performance and improving

your operation to reach these goals is both

realistic and necessary.

Step 2: Collect Information

The second step in gaining control of a

part of your business is collecting

information to see how your farm

compares with other dairy farms. Many

producers would benefit from using

computerized year-end analysis

programs, such as the one used to

compile the Ohio Farm Business

Analysis Dairy and Crop Summaries,

New York Dairy Farm Business Summary,

the Northeast Dairy Farm Summary, or

FINBIN summaries maintained by the

Center for Farm Financial Management

at the University of Minnesota.

8

The FINAN program, one of the

FINPACK programs supported by the

Center for Farm Financial Management, is

used by Extension in Ohio and 30 other

states to make such calculations. The

FINAN analysis will calculate most of the

financial ratios listed in the 15 measures.

The records needed to complete an

analysis are beginning and end-of-year

balance sheets, performance information,

and cash records with accrual adjustments.

If you use the FINAN program for several

years, you can easily see and evaluate

business trends over time.

Step 3: Monitor Your Progress

The third step in gaining control of your

business is monitoring your progress —

that is, comparing how you are doing with

your goals. Make this comparison while

the information is still timely, especially

for many management factors that change

weekly or monthly. Finding out today that

the ration you were feeding six months

ago caused a major drop in production is

not very helpful. However, some measures

like the debt-to-asset ratio only need to be

calculated once per year if your operation

does not undergo any major financial

changes.

To see how monitoring works, consider

this example:

The management team sets a goal of

lowering the operating expense ratio

(Measure 3) to no more than 70%. First,

a budget is developed to meet the goal.

Next, someone is assigned the

responsibility of measuring and

monitoring income and expenses

regularly (probably monthly) throughout

the year. If either factor changes, the

team takes corrective action in time to

keep the expense ratio in line. If the

person collecting the information is not a

manager, he or she should report the

information to a designated member of

the management team.

Key, yet often overlooked, management

issues are:

(Step 1) Who is responsible for setting

goals?

(Step 2) Who is collecting information to

monitor progress?

(Step 3) Who, when, how is progress

against set goals monitored?

Frequently, different people set goals,

collect information, and monitor different

parts of the business. Important questions

are:

•

Does someone have the responsibility

for performing each of these steps for

each goal?

•

How often is this person to do it?

•

With whom are they to

share the

information?

•

What is this person to do if they find a

major problem?

Management must ensure that someone

is responsible and follows through!

9

Step 4: Take Corrective Action

The fourth and most important step is

taking the appropriate corrective action, if

needed. If the business is meeting a goal,

no action is required unless the goal

should be adjusted to increase long term

farm sustainability. If the business is

exceeding a goal, action may still be

necessary. If the goal is exceeded because

of desirable behavior by one or more

people in the business, management may

want to praise and reward those who

helped exceed the goal. Management may

also want to consider whether the goal is

set too low, but management must be

careful not to discourage high perf

o

r

m

e

r

s

b

y

r

a

i

s

i

n

g

t

h

e

g

oa

l

a

n

d

“

r

ew

a

r

d

i

n

g

”

h

i

g

h

performance with even higher

expectations.

If the goal is not met, management should

do one of two things — take corrective

action based on why the goal was not met,

or consider if the goal is unrealistic and

needs to be re-evaluated. Taking corrective

action includes identifying problems and

implementing the necessary steps to remedy

the situation.

Managers who make things happen are able

to identify the cause of a

p

r

o

b

l

e

m

, and

t

h

e

n

s

o

lv

e i

t

.

T

h

e

y

u

s

u

a

lly

a

s

k

“

W

h

y

?

”

u

n

t

i

l

they

fully understand what is causing a problem.

Then they entrust others to help solve the

problem while continuing to ask why and

what will be affected by these changes.

10

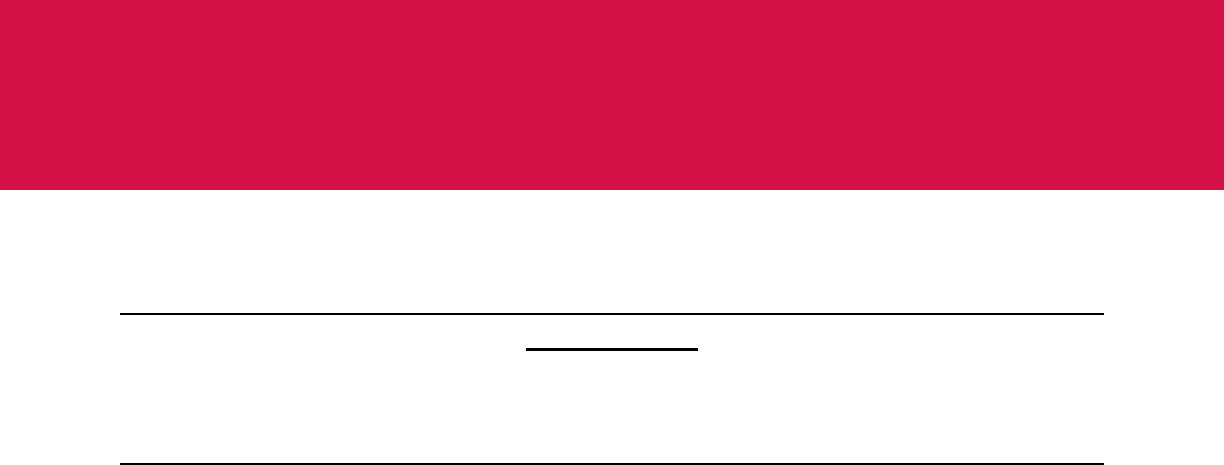

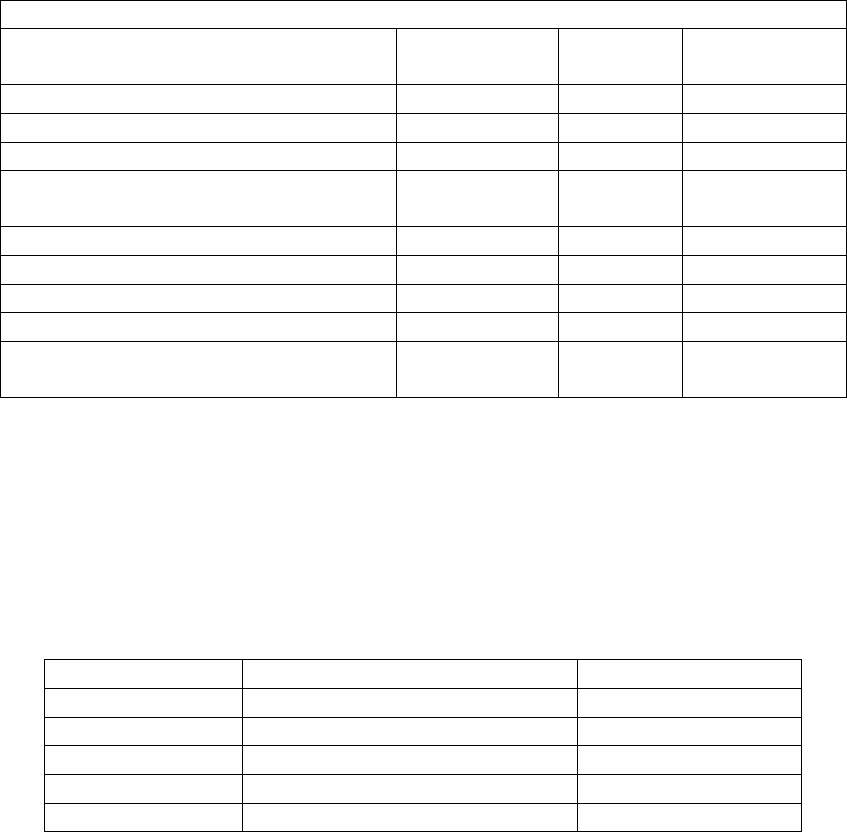

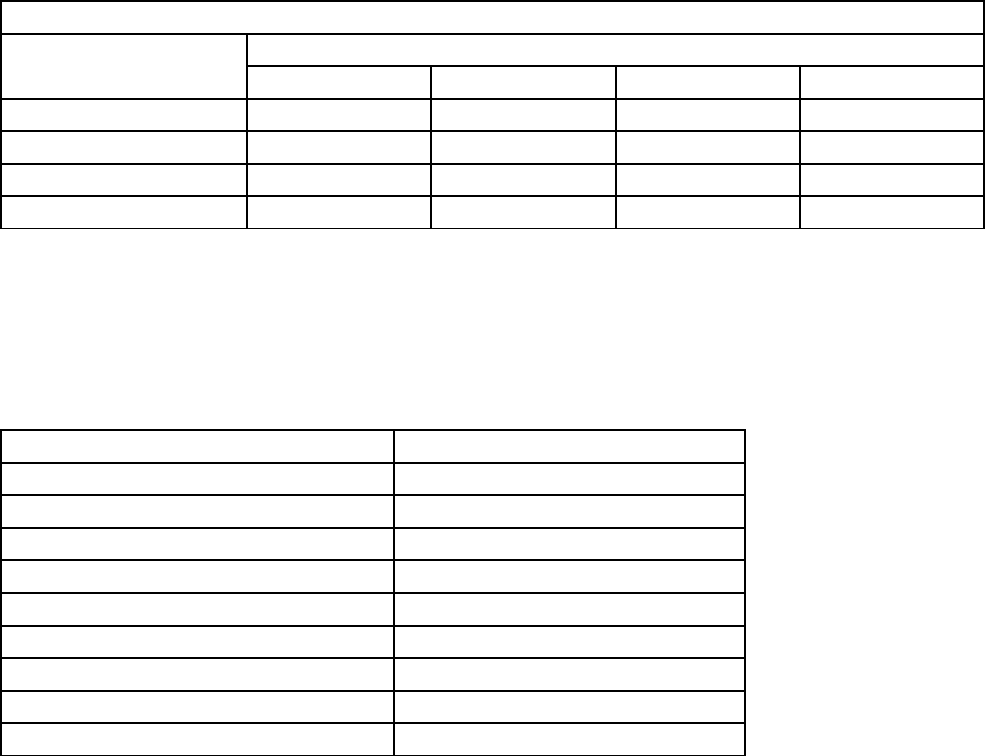

The 15 Measures

Rate of Production

1. Pounds of milk sold per worker

Freestall /parlor

≥

1,000,000 ECM

Cost Control

2.

Feed cost per cwt of milk sold Top 25%

Income over feed cost

3.

Operating expense ratio (OER)

≤

70%

Capital Efficiency

4.

Dairy investment per cow

≤

$11,000 per cow

5.

Asset turnover ratio (ATR)

≥

0.60

Profitability

6.

Net farm income (NFI)

≥

$1,300 per cow

7.

Rate of return on farm assets (ROA) > 10%

Liquidity

8.

Current ratio (CR) and CR 3.0 to 3.5

Working capital (WC) WC ≥25% of gross revenue

Repayment Schedule

9.

Scheduled debt payment < 10 % of gross receipts

(principal, interest, and

capital lease payments). <

$400 per cow

Measure Competitive Level

11

Solvency

10.

Debt to asset ratio

≤

30%

11.

Debt per cow

<

$3,300 if not expanding

<

$4,300 during

expansion

Mission

12.

The management team agrees on why

they are in business

Written mission

statement

Maintain Family’s Standard of Living

Motivated Labor Force

14.

Managers use personnel management practices that lead to well-

trained, enthusiastic, and empowered family members and

employees who share a commitment to the mission and goals of the

business.

Manure Nutrient Management

15.

Cost associated with manure removal from the farm is often $125 to

$150 per cow. Proper utilization of manure can minimize this cost

and reduce environmental risks.

13.

Owner/operator(s) maintain or increase

their standard of living by continual

change to adopt proven technology,

capture economies of size, or market

opportunities so that the family(ies)

supported by the business can maintain

their standard(s) of living.

5 to 10% of gross

farm income

Measure Competitive Level

12

Measure 1

Rate of Production:

Pounds of Milk Sold per Worker

Competitive Level: 1,000,000 lb of ECM per worker

Energy Corrected Milk (ECM) = (7.2 x lb protein) + (12.95 x lb fat) + (0.327x lb milk)

Calculation:

Total pounds of ECM milk

sold ÷ full-time worker

equivalents (FTE)

Example:

8,500,000 lb ECM milk sold

÷ (20,000 hours/2,500 hr)

= 1,062,500 pounds milk sold per worker

The increasing cost of labor, combined with

its impact on the overall cost of production

means a dairy manager needs to measure,

evaluate, and monitor labor efficiency. An

excellent way to accomplish this is by

calculating the pounds of energy-corrected

milk (ECM) sold per full-time worker. This

efficiency factor combines labor efficiency

and dairy herd productivity into a single

indicator.

The calculation of this measure is

significantly influenced by your definition of

a full-time equivalent (FTE). In Ohio, an FTE

is often defined as an adult who works 50

hours per week for 50 weeks (allowing for two

weeks of vacation). This translates into 2,500

work hours for each FTE. It is vital that you

include all paid and unpaid labor in this

calculation. Smaller dairy farms are more

likely to have at least some unpaid family

labor from a spouse, children, or the operator

who likely works more than 2,500 hours per

year.

When

analyzing and comparing your farm to other

benchmark data, it is important to determine how the

reporting agency defines a full-time worker, and if

crop production labor is included.

To calculate this measure:

1.

Calculate total FTE on the farm per

year. Divide total hours of paid and

unpaid labor

f

o

r

p

r

od

ucing

y

our

dairy’s

f

ee

d

cr

o

ps

and

f

o

r

operating the dairy by

2,500.

2.

Calculate total pounds of ECM. Total

pounds of fat, protein, and milk sold

should be taken from the year’s milk

checks.

Herd average figures from dairy

record systems are not an accurate

reflection of milk sold because they

include fresh cow milk, milk discarded

from treated cows, and milk fed to

calves. The pounds of salable milk fed to

calves should be added to pounds of milk

sold to reflect total potential milk sales.

3.

Divide total pounds of ECM sold by total

FTE per year.

13

Pounds of ECM sold per worker is an

important tool for evaluating the productivity

of workers and cattle. It combines efficient

labor utilization with good to excellent herd

production. If all feed is purchased, the general

rule is to double these benchmarks.

Because free-stall parlor systems can handle

more cows, these systems allow more pounds

of milk per year per worker than tie stall or

stanchion systems. Tie stall or stanchion

barns entail considerably higher costs per

cow than larger, modern free-stall facilities.

The combination of lower investment per

cow and more efficient labor utilization make

free-stall housing systems much more

economical because they generally result in

lower costs for producing each unit of milk.

However, existing tie stall or stanchion

facilities may be able to compete with free-

stall systems if the operation carries little or

no debt.

Fewer pounds of milk per worker will likely

be sold per year for small versus large breed

herds, but the value of ECM sold per year

may be similar under similar management

systems. This occurs because of the higher

value per cwt of milk for the small breeds of

dairy cattle (milk is higher in concentration

of fat and protein). However, because the

value of milk sold is affected by milk price

fluctuations, gross milk sales is not a very

useful tool for measuring productivity trends

over time.

If the pounds of milk sold per worker is below the

competitive level:

1.

Evaluate herd productivity.

To achieve the

desired level of pounds of ECM sold per

worker, cows will most likely need to be

above average in production for their breed.

Many competitive farmers implement

strategies to increase herd productivity.

Some strategies include feeding balanced

rations, optimizing cow comfort, using

proven milking technologies, improving cow

flow in parlor, milking more than two times

per day, and filling facilities over 100% when

labor is only slightly affected.

2

.

Evaluate labor efficiency. Antiquated facilities

and uncomfortable working conditions

reduce labor efficiency. Careful hiring also

plays an important role in labor efficiency.

Employee training, motivation, and pride in

doing a job well help workers to be more

efficient and effective, whether they are

family members or unrelated employees.

Workers in tie stall or stanchion systems

should be able to handle 30 to 35 cows per

FTE, including raising crops. Workers in

free-stall systems should be able to handle

40 to 50 cows per FTE, including raising

crops. Efficiently operating parlors will turn

a minimum of 4 times per hour.

3. Apply the four steps in the Gaining Control of

Your Business

section in the Introduction: set

a realistic goal, collect information for your

own farm, compare your performance with

the goal, and take appropriate corrective

action, if needed.

14

Measure 2

Cost Control: FEED

Feed Cost per Cwt of Milk Sold and

Income Over Feed Costs

Competitive Level: Top 25% (low feed cost or high IOFC)

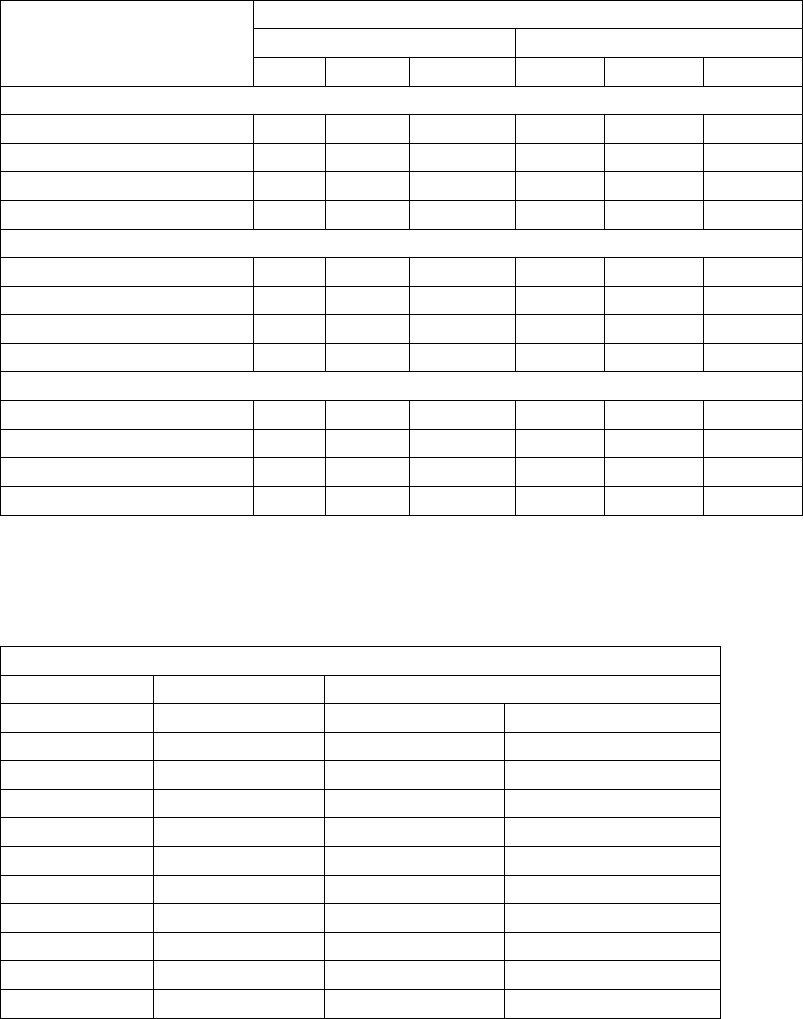

Feed costs per cwt of milk sold and income over feed costs (IOFC) can be quite variable from

year to year among farms because of market and management influences and which animal

groups are included in the calculation. Calculations based on different animal groups can

include:

• Total feed costs per cwt of milk sold (includes lactating and dry cows and heifers of all

ages)

• Feed costs per cwt of milk sold for lactating cows (lactating cows only used because they

generate the revenue)

• Feed costs per cwt of milk sold for lactating and dry cows (sometimes used because

heifers are raised off the farm)

• IOFC is typically calculated for lactating cows only

The current feed costs should be calculated using the following web site:

https://dairy.osu.edu/resources/financial-management. The goal is to be in the top 25% (low

feed cost or high IOFC) or green level. If herd replacements are custom raised, then feed costs

per cwt milk sold should be about 30% lower than for when costs for all animals are included.

Example calculation of total feed costs for the herd per cwt milk sold:

A. Total cost of feeds fed to all

dairy cows (lactating and dry)

and replacement heifers,

including both purchased and

homegrown feeds

$ 408,000 purchased feed

+ $ 370,000 homegrown feed

= $ 778,000 total feed

B. Total cost of feeds fed to dairy

herd ÷ total cwt of milk sold

(for the same time period)

÷ 85,000 cwt of milk

= $ 9.15 feed cost per cwt of milk

sold

15

Feed Cost Per Cwt of Milk Sold

Total feed costs per cwt of milk sold is a

measure of the effectiveness of management

in controlling the largest cost item in

producing milk. This measure accounts for

all of the feed provided to the lactating

cows, dry cows, and heifers since the sale of

milk is the primary revenue stream for

paying for all feed expenses. Generally, 65%

of the feed costs for a dairy herd that raises

its own replacements will be for the

lactating cows, 30% for the heifers, and 5%

for the dry cows. We suggest using the

market value for homegrown feeds fed to

livestock if you do not know your actual

cost of production. Feed harvested by the

cows or heifers from pasture can be valued

based on the value of hay.

Some dairy farmers can purchase feed more

cheaply than they can raise it. Different

ways of determining the cost of producing

your feed can be found on the web at

http://dairy.osu.edu/resources/financial-

management. Comparing feed production

costs with market prices will help you

evaluate the efficiency of your cropping

program.

The New York Farm Business Summary

uses cost of cash crop inputs to represent

homegrown feed costs, but this calculation

does not include machinery costs. For this

analysis, calculate all machinery costs and

allocate a portion to the crops used as dairy

feed.

Reducing cash outlay for purchased feed is

not necessarily a good way to reduce feed

costs. Homegrown feed is sometimes more

expensive than purchased feed. If purchased

feed costs per cow are kept too low, milk

production may be less than optimal, and

feed cost per cwt of milk sold may still be

high.

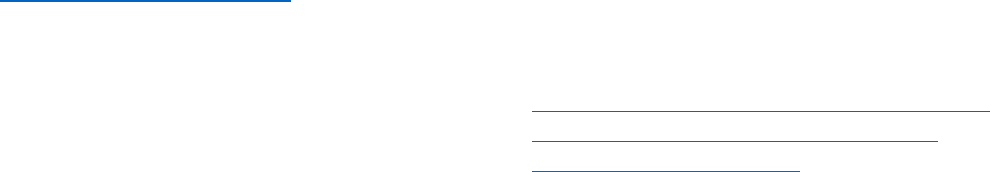

Example calculation of feed costs for lactating cows per cwt milk sold:

Example calculation of IOFC for lactating cows:

(Total value of milk sold - total cost of feed fed to lactating cows) ÷ cwt of milk sold

$300,000 purchased feed

+ $276,000 homegrown feed

= $576,000 total feed cost

85,000 cwt of milk * $16/cwt = $1,360,000

($1,360,000 – 576,000) ÷ 85,000 cwt of milk = $9.22/cwt milking herd IOFC

A. Total cost of feeds fed to lactating

cows, including both purchased

and homegrown feeds

B. Total cost of feed for lactating

cows ÷ cwt of milk sold

$300,000 purchased feed

+ $276,000 homegrown feed

= $576,000 total feed cost

÷ 85,000 cwt of milk

= $6.78 feed cost per cwt milk sold

16

When you use market price or purchase

most of your feed, feed costs will fluctuate

with market prices.

If you find that you are not meeting your

feed cost goals, consider these actions:

1. Produce or purchase quality forages for

all cattle. You cannot afford to feed poor

quality forages. However, quality of feed

should be appropriate to the animal’s

nutritional needs. High producing cows

need the highest quality forage; that

same quality would be wasteful for

gestating heifers or dry cows.

2. Use grouping strategies and appropriate

diets based on animal needs (parity, milk

yield, body condition, etc.) By grouping

lactating cows, higher quality forages

can be fed to the higher producing cows

and lower protein diets and less use of

feed additives can occur for late lactation

cows.

3. Balance rations for all groups based on

current feed analyses and judicious use

of feed additives. Make sure that the

rations are balanced for reasonable

levels of production (over-formulate at a

reasonable level, e.g. 5 lb above group

average, but this should be based on the

variation of milk yield within the group).

Make sure dry matter intake is at

expected levels.

4. Keep crop production input costs low by

using manure nutrients, testing soil, and

making wise purchases of seed,

fertilizer, and chemicals.

5. Reduce feed losses from storage, losses

during mixing and delivery, and refusals

at the feed bunk. Collectively, all of

these feeding losses are referred to as

shrinkage and are included in the feed

costs per cwt of milk.

6. Keep purchased feed costs low by wise

buying practices (e.g., feed commodity

contracting, purchasing “bargain” feeds,

etc.) and efficient use of feed (e.g.

feeding ingredients to appropriate

animals and reducing wastage).

7. Keep crop equipment costs per acre low

by using custom operators, purchasing

expensive machinery with neighbors, or

purchasing feeds.

8. Feed for high production if cows have

the genetic ability and you have

adequate facilities and sound animal

health. Management areas limiting feed

efficiency (e.g., high incidence of

mastitis, lameness, or metabolic

diseases; or over-stocked, poorly

ventilated facilities) should be improved

before feeding for higher milk

production.

9. Keep dry periods between 45 to 60 days

and address problems with reproduction

and animal health.

10. Keep non-dairy culling (<25%) and

death (< 5%) rates low in herds; if these

two aspects are well managed, overall

cull rate (dairy, non-dairy, and deaths)

may have little impact on farm

profitability.

11. Keep age at first calving between 22 and

24 months to reduce costs per

replacement animal.

12. Eliminate causes of low milk production

such as poor cow comfort, mastitis, and

poor feed bunk management.

Farms can simultaneously have low feed

costs per cow and extremely high feed costs

per cwt of milk sold. This is frequently a

result of feeding poor-quality forage and/or

not balancing the ration for optimal

production, resulting in low production.

17

Also, errors in feed mixing and delivery can

have adverse effects on milk production and

feed costs. Feed tracking software for TMR

mixers can help monitor accuracy of feed

weighing and delivery. Also, make sure

animal inventories by group and age are

accurate.

Total feed costs will also be influenced by

how calves and heifers are reared. Longer

milk-feeding periods and feeding for higher

rates of gain in the pre-weaned period will

increase costs, while restricted milk feeding

and early weaning will decrease total costs.

However, overall health and performance

must be considered, as well as the targeted

age at first calving when calf-raising

strategies are considered.

Income Over Feed Costs

Routine monitoring of IOFC for a given

farm is important. The actual farm’s IOFC is

calculated based on the yield of milk, milk

fat and protein composition, and the price of

the milk and its components paid to the

farmer. The feed costs should include the

value of the homegrown feeds and the

purchased feeds provided only to the

lactating cows. The benchmark value is

calculated based on the requirements of net

energy of lactation, metabolizable protein

and effective NDF to produce the given

amount of milk, milk fat, and milk protein

produced on the farm as described and the

prices for these nutritional components

based on current market feed prices using

Sesame

®

(http://www.sesamesoft.com/) .

If your IOFC is low relative to the

benchmark:

1. Review the feed costs to determine if

there is some cost reduction available

with the homegrown feeds or to

determine if you should continue growing

these feeds or if you should buy them

from someone else. Are your purchased

feed costs too high because of greater

scrutiny needed in shopping for ration

ingredients or do you need to improve

forage quality?

2. Are the diets correctly formulated and

adjusted routinely based on changes in

feed sources or composition of feeds?

Are cows grouped adequately to feed

them based on nutrient needs and dry

matter intake (DMI)?

3. Are the DMI values used actual or

estimated from when the ration was

formulated?

4. What is the feed efficiency on your farm?

Feed efficiency on dairy farms affects

IOFC. One common method to calculate

feed efficiency is: 3.5% fat-corrected

milk (FCM, lb) / DMI (lb). The equation

for calculating 3.5 FCM (lb) = (0.432 x lb

milk) + (16.23 x lb milk fat). The desired

range for this feed efficiency is 1.4 to 1.6.

The goal is usually to increase DMI, but

if the intake increases without a response

in milk yield, then some other positive

response (e.g., improved body condition

or fertility) should be occurring or the

increase in feed costs is not generating an

economic return.

5. Is milk income too low relative to current

market potential? Should another milk

processor be considered? Are milk fat

and protein at expected levels relative to

breed averages? Are you getting milk

quality premiums based on low somatic

cell and bacteria counts?

18

If your IOFC is high relative to the

benchmark, this would usually be a positive

indication, as long as the numbers used are

accurate. A few areas to review are:

1. How did you price the homegrown feeds;

in other words, were all costs of

production for these feeds included?

2. Were the costs of feed refusals and feed

shrinkage included in total feed costs?

3. Are the DMI values used for calculating

feed costs actual and not estimated

values?

4. Check body condition of all cows in the

herd. If cows are overall low in body

condition, the high IOFC is likely

temporary in that the cows have been

losing body weight to support the milk

yield. Fresh cows are expected to lose

one body condition score (1 to 5 scale)

during the first 60 days in milk, but

otherwise, cows should be in a positive

energy balance.

Determination of IOFC for short periods of

time should be avoided (yearly preferred),

but if conducted, make sure the same time

period for feed costs and milk yield and

income are used. For example, a high IOFC

for a short time frame comparison may be

inflated due to a transient increase in milk

price. In such cases, a longer time frame

should be used or a more realistic milk price

used that reflects a more extended period of

time.

19

Measure 3

Cost Control:

Operating Expense Ratio (OER)

Competitive Level:

Less than or equal to 70%

Calculation:

(Total cash operating expenses -

farm interest expense)

÷

gross farm income x 100

Example:

$ 1,088,000 expenses

-

$ 52,000 interest

= $ 1,036,000 total operating expenses

÷ $ 1,450,000 gross farm income

= 0.71

x 100

= 71% OER

This ratio indicates the percentage

of the gross farm income used to

pay operating expenses. Expenses,

not including interest, should be

less than 70% of the gross farm

income of a dairy business. When

the percentage is lower, more

money is available for loan

payments (principal and interest),

family living, improvements, and

savings.

Take total cash operating

expenses directly from Form

1040, Schedule F for the year

being analyzed. These represent

cash expenses that may or may

not include all of the expenses

incurred for production of milk in

the year being analyzed. Make

these (accrual) adjustments as

needed:

1.

Subtract the depreciation expense

from Form 1040.

2.

Subtract expenses that were prepaid

for future production.

3.

Add expenses that were prepaid in

the previous tax year for items that

were used to produce milk in the year

being analyzed.

4.

Add expenses for items that were used

to produce milk but were not included

on the Form 1040. This would include

unpaid bills.

5.

Subtract any expenses that were paid

in the year being analyzed for items

used in previous production years.

20

Gross farm income includes cash farm

income adjusted for changes in inventories

from year to year. If for example, you have

the same number of livestock in one year

as the previous year, except for five

additional springing heifers worth

$10,000, add this $10,000 to gross farm

income. If you have $20,000 less feed on

hand than in the previous year, reduce

gross farm income by $20,000.

Farm interest expense includes all interest

expenses reported on Schedule F.

If the operating expense ratio is lower than

70%:

Low expenses are desirable only if

production and income do not suffer. If

expenses are below 70% and production

per cow is above that for similar animals,

great!

If expenses are low, income is low, and

cash flow is tight, the business may not be

large enough to generate sufficient income

or debt may be high. Look first

at other

ratios that measure output and volume of

business. The business also might have too

much debt, since principal and interest

payments are not included in operating

expenses. Check the current ratio and the

debt-to-asset ratio for clues about

excessive debt.

If the operating expense ratio is higher

than 70%:

An operating expense ratio above 70%

may reflect high expenses, low income, or

both. The largest single expense on most

dairy farms is feed. Make sure that feed

costs per cwt of milk sold are reasonable.

Are other expenses out of line or reported

in the wrong year?

Another reason for the operating

expense ratio to exceed 70% is low gross

farm income. Look at the asset turnover

ratio, milk sold per worker, and perhaps

the

f

a

rm’s

i

n

v

e

s

t

m

e

n

t

pe

r

c

o

w

f

o

r

c

l

u

e

s

a

s

t

o

wh

e

t

h

e

r

g

r

o

ss

farm income is too low

or the farm is too small.

21

Measure 4

Capital

Efficiency:

Dairy Investment per

Cow

Competitive Level: Less

than or equal to

$11,000

per cow

Calculation:

Total dairy investment ÷ number of

cows

(lactating and dry)

Example:

$2,500,000 total dairy investment

÷

349 cows

= $ 7,353 investment per cow

Total dairy investment is the total current

m

a

r

k

e

t

value of all dairy

assets.

These

assets

should only include land used for

raising

livestock feed,

past

ur

e, livestock

buildings, feed

storage,

manure disposal,

livestock

machinery, milking equipment,

cows

a

n

d

replacements, and other

investments related to

t

h

e

dairy

e

nt

e

r

p

r

ise.

This measure indicates how

efficiently

the

money on

a

dair

y

farm is

invested. Excessive

investment per cow makes

receiving

a high

return on the dollars invested

difficult.

If

investment per cow is greater than $11,000,

also look at the

asset

turnover ratio (Measure

5),

r

e

t

u

r

n

on farm

assets

(Measure 7), and

debt per cow

(

M

e

a

s

u

r

e

11). If the business is

generating a high return on assets and is not

carrying

excessive

debt per

cow,

a

hig

he

r

investment per cow is

manageable.

If this is

not

the

c

a

s

e

,

when investment per cow is high,

your dollars are not working hard enough to

generate dairy inc

o

me.

If dairy investment is more than $11,000 per

cow:

The first question to answer is: What is out of

line? Is the investment too high? Is the number

of cows too low? Or both? High investment per

cow may stem from a number of causes

including:

1. High-priced land,

2. Overbuilt facilities,

3.

Large

number of owned acres per cow,

4. New or overpriced

ma

c

hine

r

y,

5. New or overpriced/oversized facilities,

6. Robotic milking and feeding systems, or

7. Some combination of the above.

22

In Ohio, some farms have land that is now worth

m

uc

h

more for non-agricultural

uses

than the

ag

r

icult

ur

al

value that the owners

originally

paid.

If the

f

a

r

m

is profitable and they

wish

to continue

their dairy business on this land,

we suggest

assigning

a reasonable agricultural

value

to the

land for these calculations.

If high-priced land

was

recently purchased at

market values or nonagricultural

value

and the

cows

are expected to pay for the land, use the

purchase price for the land for this calculation.

Lowering investment is difficult. Rationalizing

why investment is more than $11,000 per cow is

easy; however, you should address the problem

because your dollars are not working hard

enough. The usual solutions to high investment

per cow include:

1. Restraint on future

in

v

est

me

nt

2. Increasing cow numbers without

f

u

rt

h

e

r

increases

in

in

v

est

me

nt

3. Trading a farm in a high-land value area for a

larger farm in a lower-value area

4. Leasing assets instead of purchasing them

5. Selling unproductive assets.

The number of

cows is too low

if the

facilities are

not

full. Filling

the

barns

with

high-producing cows

a

l

m

o

s

t

always pays.

Many competitive farmers

fill

t

h

e

i

r

buildings above

100%

of capacity.

Sometimes, it is possible to increase cow

numbers by making alternate arrangements for

the care and housing of dry cows and

replacement heifers. Be cautious that custom

raising expenses or facility rentals do not

increase overall cost more than additional

income. What would it take to increase the

number of cows on your farm by 10%?

23

Measure 5

Capital Efficiency:

Asset Turnover Ratio (ATR)

Competitive Level: Greater than or equal to 0.60

Calculation:

Gross farm income ÷

average

total farm assets

Example:

$1,450,000 gross farm income

÷ $2,400,000 average total farm assets

= 0.60 ATR

The

ATR

measures the

efficiency

by which all

f

a

r

m

assets

generate revenue. The higher the

ATR,

the

more

efficiently assets

generate revenue.

Gross farm income includes cash farm inc

o

me

adjusted for

changes

in inventories from year to

year.

If for

example,

you have the same number of

livestock i

n

one year as the previous

year,

except for

five

a

ddit

ional springing

heifers

worth

$10,000,

add

this

$10,000

t

o

gross farm income. If you have

$20,000 less

feed

o

n

hand than in the previous

year,

reduce gross

far

m

income by

$20,000. Average

total

farm

assets

is

t

h

e

average

of the total farm

assets

at

the beginning and

at

the end of the year.

Farms that should have a higher

ATR

are those

t

h

a

t

rent their

facilities

or that rent some or all of the

land that they might use to grow crops. Farms with

greater investments in land or

very expensive

land

and/o

r

facilities usually

have a

lower ATR.

It is up

to

the

individual dairy business to determine if the

r

e

t

urn

the business is generating is

acceptable

relative

to

the

investment in these assets.

If the asset turnover ratio is below 0.60:

The first question to answer

is:

What is out of

line?

Are

the gross revenues too

low,

are

average

total

far

m

assets

too high, or are both causing

problems?

On

dairy farms, the quantity of

milk sold and the milk price impact gross

revenues most

significantly.

If milk

production per cow is normal, herd

size

is

a

d

e

q

uat

e,

cull and other

sales

are normal, and

milk prices are

not

depressed,

then the

problem may be with total

f

a

r

m

assets.

Many dairy farmers commonly tie up more

money

i

n

their farms than is

necessary

to run

them. For example, due to

large

investments

in land and

large

e

q

uip

me

nt,

grain farmers

usually

have a

lower ATR

than dairy farmers.

Dairy farms are also seeing lower ATR as

they invest in large harvest equipment; some

operations may benefit from custom hiring

some harvest or other field operations. Some

dairy farmers could increase

t

h

e

i

r

net

incomes and their

ATR

by reducing the

acreage

of crops they raise and better

managing the dairy enterprise.

Building

new

facilities,

such as parlors larger than herd

size

dictates, can cause

low ATR.

Once

b

uilt, only

generating more income

relative

to the

in

v

est

me

nt

will

change the ATR.

24

Another factor that can cause a

low ATR

is

hig

h-

p

r

ice

d

land. The

value

of some dairy

far

me

r

s

’

land has increased

significantly

as a result of

urban and

o

t

h

e

r

development pressures. Higher

land

values

r

e

d

u

ce ATR.

If the

cows

are not

being asked to pay for

t

h

e

high-priced land (the

land

was

purchased before land prices

increased), the dairy operator may be satisfied

with a

lower ATR

as long as the farm is

profitable

a

n

d

meeting other goals.

If

asset levels

are reasonable (see Measure 4,

dairy investment per cow), production

issues

may be causing a

low ATR.

Many competitive

farmers adopt new management

practices,

cautiously overfill

their

facilities,

and milk more

than two times per day to reap the most

p

r

o

fi

t

from their investments.

Most people do not

like

to move their

businesses.

This reluctance, along with the

desire to hold on to

t

h

e

property until the price

goes

higher,

causes

some

far

m

businesses

to stay

on high-value farms when pe

r

h

a

p

s

they should

not. If the farm

family

has

a

d

e

q

u

a

t

e

income to

live

on and the land is appreciating enough to

justify

continued ownership, then a

low ATR

may be

acceptable. However,

a business

struggling

to pay the

bills

and provide for

family

living

should strongly consider cashing in or

trading the

far

m.

FINPACK

uses a different method of computing

ATR than the

New York

Farm

Business

Summary (NYFBS). Both methods are

acceptable,

but they

give

different results. The

NYFBS

uses the gross revenue

a

pp

r

oa

c

h

based

on gross farm income as shown in the previous

example. FINPACK

uses the value of farm

p

r

o

d

u

ct

i

o

n

method, which results in a

lower

ATR. FINPACK

users who want to compare with

this measure

s

h

o

u

l

d

calculate

their

ATR

manually using the

f

o

r

m

u

l

a

provided in this

section.

25

Measure 6

Profitability:

Net Farm Income (NFI) Per Cow

Competitive Level: ≥ $1,300 per cow

Calculation:

(Cash receipts

± inventory change

-

expenses

-

depreciation)

÷ number cows

Example:

$ 1,390,000 cash receipts

+ $ 60,000 inventory change

- $ 1,088,000 expenses

-

$ 50,000 depreciation

= $ 312,000 NFI

÷ 340 cows__________

= $918 NFI per cow

Net farm income per cow is an excellent

measure of how a dairy farm is doing. It

typically represents the return to labor and

management for the owner/operator. The

competitive level of greater than $1,300 per

cow

is typical of what the top 25% of

Midwest dairy farms achieve in times of

reasonable milk and feed prices.

Breaking net farm income down to a per-cow

measure is useful for comparing your farm’s

performance to other farms within production

years regardless of breed or herd size.

How is NFI used?

Part of NFI will be withdrawn for reasonable

family living expenses and retirement

savings. NFI must also be used for making

scheduled principal payments on loans,

paying income taxes, and reinvesting in the

business.

Calculating NFI requires working with a year’s

receipts, expenses, inventories, and depreciation.

Receipts, expenses, and depreciation can be

obtained from the

b

u

s

i

n

e

ss’s

t

a

x

r

e

t

u

rn

.

T

h

e

s

e

c

a

s

h

-

b

a

s

e

d

fig

u

r

e

s

m

u

s

t

be adjusted to represent

all the income generated and all of the expenses

that were incurred for the

production of milk

in the year being analyzed. If the farm uses an

accrual accounting system, these adjustments

are not necessary.

Inventory change requires comparing inventory

at the beginning and end of the year. Inventory

items include grain, feed, livestock, prepaid

expenses, and accounts

r

ecei

v

a

b

l

e

a

n

d

p

a

y

a

b

l

e.

A

n

i

t

e

m’s

i

n

v

e

n

t

o

r

y

c

h

a

n

g

e e

q

u

a

ls

t

h

e i

t

e

m’s

e

n

d

i

n

g

i

n

v

e

n

t

o

r

y

v

a

l

u

e

m

i

n

u

s

i

t

s

beginning

inventory value.

26

Inventory increases for grain, feed,

livestock, and prepaid expenses are added to

income while inventory decreases are

subtracted from income. If accounts

payable increase, the amount of the

increase is subtracted from income. If

accounts payable decrease, the amount of

the decrease is added to income. If

accounts receivable increase, the increase is

added to income, but a decrease is

subtracted from income.

Computer programs, such as FINAN

®

, or

paper systems, such as the Ohio Commercial

Farm Account Book and Balance Sheets, are

helpful for calculating NFI.

For a dairy farm business to be competitive,

its NFI must, in most years, considerably

exceed the amount needed for a good family

living and to meet all scheduled principal

payments and tax obligations. In years when

it is not, only the most urgent obligations are

met. Most competitive operators routinely

reinvest in the business, maintaining and

upgrading facilities to increase efficiency.

However, diversifying into savings and off-

farm investments are also good strategies to

consider.

The goal for net farm income per cow should

allow farm managers to build working capital

reserves essential to surviving in today’s dairy

economic environment.

The NFI per cow of the high 20% of farms in the

2016 Ohio Dairy Farm Business Summary was

$949 per cow, down from the $1,392 average for

the previous 5 years (2011 to 2015). During that

same five years, the high 10% of farms

participating in the New York Farm Business

Summary averaged $1,552 per cow while the high

20% of the herds with 300 cows averaged $1,491.

The high 25% of herds in the Northeast Dairy

Farm Business Summary averaged $1,274 NFI per

cow (2011 to 2015).

If net farm income per cow is below the

competitive level this may be the result of:

1.

Productivity problems — per cow returns

are low,

2.

Size problems — fixed or overhead

expenses need to be spread over more

cows,

3.

High debt per cow (Measure 11), or

4.

Expenses are too high (Measures 2 and 3).

If you are not meeting your income

goals, consider these actions:

1.

Increase returns per cow. You can accomplish

this by reducing costs per cow, especially feed

costs, or increasing production of milk and/or

components per cow.

2.

Sell off under-used assets and pay down debt.

3.

Expand the number of cows, if you are

in the financial and managerial

position to do so.

4.

Find lower-cost ways of running the business.

27

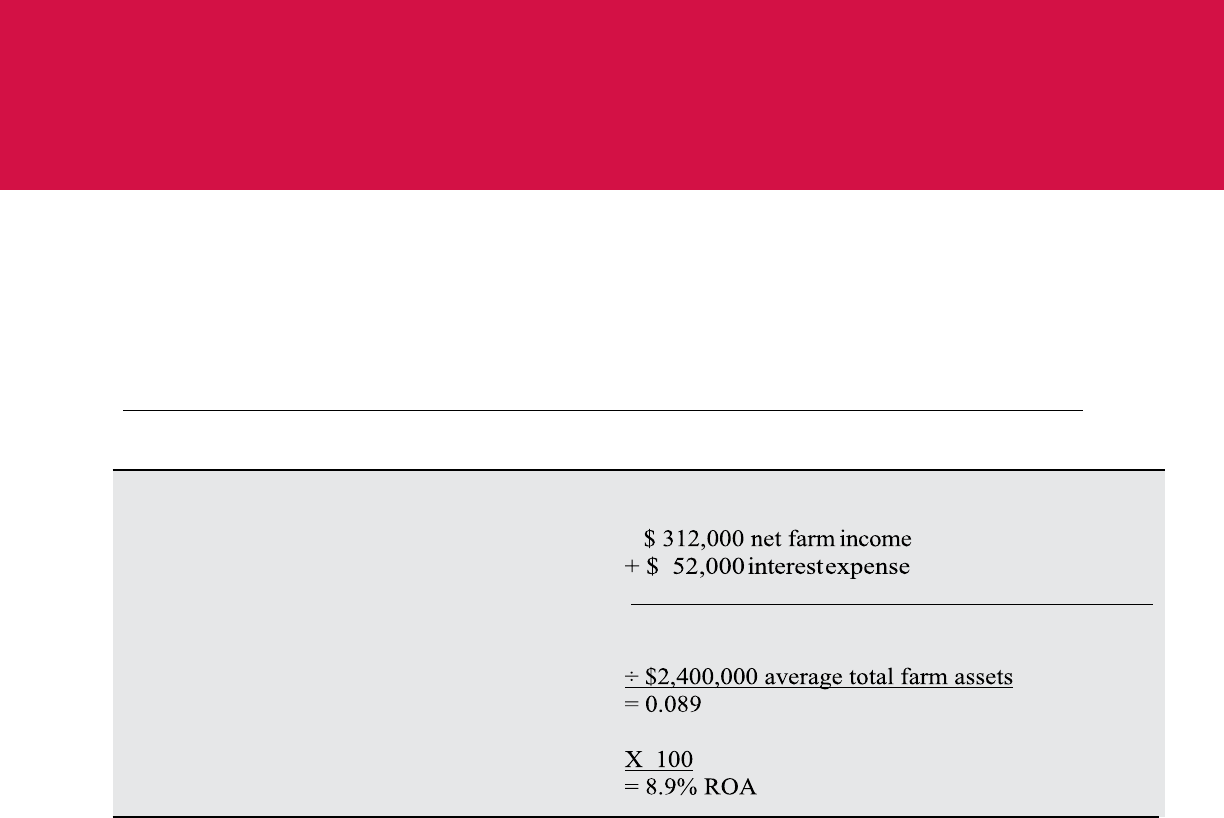

Measure 7

Profitability:

Rate of Return on Farm Assets (ROA)

Competitive Level:

Greater than 10%

ROA is useful for determining what the

assets invested in your operation earned.

The higher the ROA, the more profitable the

farming operation. If you use current market

values to determine the worth of your assets,

you can use the ROA to compare your

earnings to those of other businesses for the

same time period. The ROA also represents

the opportunity cost of having your assets

invested in the dairy business as opposed to

investing in another business or other

investment opportunity that might generate a

higher or lower return.

See Measure 6 for instructions on

calculating net farm income and item 3 on

page 28 for calculating the value of the

operator’s labor and management.

Factors affecting rate of return on farm assets:

1.

How assets are valued,

2.

Profitability of the farm business,

3.

Level of owner withdrawals for

unpaid labor and management,

4.

Amount of unproductive or

marginally productive assets,

and

5.

Whether assets are owned or leased.

Example:

- $150,000 value of operator’s labor and management

= $214,000 return to assets

Calculation:

(Net farm income + farm interest expense

- value of operator’s labor and management)

÷ average total farm assets x 100

28

L

e

t

’

s

discuss

these

fiv

e fac

t

o

r

s

in

mo

r

e

d

etail:

1.

You may use either a cost basis or market

basis balance sheet to compare the

performance of your business from year

to year. Most farmers and lenders use a

market value balance sheet. If you use a

market value balance sheet, hold the per

unit values of your breeding stock and

long-term assets (land) constant from

year

-to-year to eliminate the impact of

simply changing asset values. Using a

cost basis balance sheet measures the

performance of your farm, unaffected by

market changes of asset values, as well as

the return on dollars invested. However, a

ROA calculated on a cost basis is difficult

to compare with the ROA of other

businesses using market valuation.

Because farm interest expenses are added

to net farm income, rate of return on farm

assets is not affected by level of debt or

how debt is structured in the farm

business. Thus, you can fairly compare

actual business performance of both

high- and low-debt operations.

2.

Return on assets will decline during years

of declining profitability. If profitability is

always low, then the farm manager must

look at ways to increase profitability. The

ROA should be higher than the interest rate

on borrowed money. If interest rates are

higher, then other parts of the business are

subsidizing the interest payments for any

new or existing debt. It is not unusual for

other parts of the farm operation to

subsidize land investments, as land typically

has a low rate of return.

3.

The Ohio Farm Business Analysis program

calculates the value of owner withdrawals

for unpaid labor and management at $13.50/

hour, plus 5% of the value of farm production

as

a management charge. The ROA may be

overstated if owner withdrawals are lower

than this, perhaps supplemented by off-farm

income. Farms set up as corporations should

calculate their labor and management charge

and compare it to the salary and benefits that

are already deducted from net farm income

as owner/operator wages and benefits. If the

calculated value of owner withdrawals is

higher, the difference between the calculated

and actual owner withdrawals should be

deducted from the net returns before

calculating return on assets.

4.

If a business has a large investment in

unnecessary and/or unproductive assets, ROA

may be low. In these situations, the farm

manager needs to inventory these assets

carefully and determine if the business could

be more profitable if the dollars those assets

represent were reinvested in other ways.

5.

Businesses leasing/renting the farm and/or

other major assets may show a higher ROA;

however, they will have higher operating

expense ratios.

The ROA for the high 20% of dairy farms participating

in the Ohio Farm Business Analysis Program from

2011 to 2015 averaged 12.2%. The high 10% of all

farms and high 20% of herds over 300 cows averaged

14.96 and 14.3%, respectively for herds participating in

the New York Farm Business Summary.

The New York Farm Business Summary also

deducts

a charge for other unpaid labor from net farm

income in addition to unpaid operator labor.

However, unless a dairy

operation has large

amounts of unpaid labor, this deduction will not

significantly affect the resulting ROA

calculation.

29

Measure 8

Liquidity:

Current Ratio and Working Capital

Competitive Level:

Current ratio (CR) = 3.0 to 3.5

Working capital (WC) = ≥ 25% of Gross Revenue

Calculation:

Current ratio

= current farm assets

÷ current farm liabilities

Working capital to gross

revenue

= ((current farm assets

–

current farm liabilities)

/Gross farm revenue) x 100

Example:

Current ratio:

$300,000 current assets

÷ $173,000 current liabilities

= 1.73 CR

Working capital:

$300,000 current assets

- $173,000 current liabilities

= $127,000 WC

÷ $508,000 gross farm revenue

= 25% WC to gross revenue

Liquidity is a measure of the farm business’

ability to pay obligations due in the coming

year from the cash on hand and assets that

can easily be turned into cash. Liquidity is

often measured using the current ratio. This

ratio is an indicator of the ability of the

current farm assets, if liquidated, to cover

current liabilities. A current ratio of 1.5

indicates that there is $1.50 worth of current

assets for every dollar of current liabilities.

The higher the ratio, the greater the

liquidity. The ratio is also an important

indicator of short-term financial viability.

Another measure of the farm’s liquidity is

working capital. Working capital is the

difference between the value of the farm’s

current assets and current liabilities.

Current assets include cash, savings, and

other assets that can easily be converted to

cash during the year (e.g., cash, stocks,

bonds, feeder livestock, accounts receivable,

prepaid expenses, and inventories, such as

feed and supplies.)

Current liabilities are financial

responsibilities that are due within one year

of the date of the balance sheet (e.g.,

accounts payable, operating loans, principal

portion of scheduled loan payments, and

other accrued expenses).

A farm business must be able to pay its

current obligations and have a cushion for

unexpected cash shortfalls. Cash shortfalls

may occur because of disease outbreaks,

30

lower than expected milk production, lower

milk prices, higher input prices, or a

combination of factors. A current ratio (CR)

above 1.0 indicates that a farm has more

current assets than current liabilities. A

competitive dairy farm must pay its bills and

keep its bank obligations up-to-date.

A CR of 2.0 is sometimes indicated as being

strong, but with highly volatile milk

markets, this is not high enough. While

receiving milk checks on a regular basis

helps with cash flow, long term declines in

milk price require cash reserves to pay bills

as they are due. The top farms have a CR of

3.5, while average farms that often struggle

during market recessions have current ratios

of only 2.7.

If the current ratio is low:

A persistently low current ratio indicates a

major cash flow problem. Strategies to

improve the farm’s current ratio include:

1. Refinance existing debt with longer

repayment terms,

2. Sell nonessential intermediate or

long-term assets (e.g., machinery and

investments), using the proceeds to

reduce debt or improve the

efficiency of the dairy business.

3. Increase the farm’s revenue or

decrease expenses, focusing on

profitability.

A low CR may be the result of a lender

extending non-mortgage credit on very short

terms, for example, when large pieces of

equipment, such as large balers, choppers, or

combines, are financed for three years or

less. This strategy results in ratios

substantially lower than 1.0 for some

farmers because large amounts of principal

are due each year. Cash flow is typically

very tight.

This is not problematic as long as the farm

is profitable enough to make the payments

and the lender continues to extend credit.

Extending non-mortgage credit gives the

lender more control over the loan and the

farm. These loans usually are reviewed and

renewed at least annually. This large "line

of credit" causes some farmers problems

when they have bad years and their lenders

will not extend additional credit.

Also, other lenders may consider the farm

a high risk because of its poor CR. A low

CR is usually a minor problem when the

farm is profitable and the debt-to-asset

ratio is well below 30% (Measure 10).

However, this is not a long-term answer,

but rather a short- term fix. With price

volatility, it is important to have cash

available to cover expenses when prices

are below breakeven.

31

If the current ratio is high:

A high CR indicates surplus cash, which

needs to be wisely invested to protect the

farm from market down turns. Current

assets usually generate lower returns than

other assets. If your CR is high, consider

investing in assets that generate higher

returns (yet allow cash to be accessed when

needed).

Working capital

Working capital is another way to evaluate

the farm’s liquidity and is a measure of the

margin of safety in dollars, rather than as a

ratio, of the farm’s ability to meet short-

term liabilities. The amount of working

capital that is adequate is dependent upon

the size and scope of the farm business.

However, a common recommendation for

farms is working capital equal to 25% of

gross revenue.

Benchmarks for CR:

Business Summary: New York State, Cornell

University, 2011-2015, All Farms, average

= 2.62.

Business Summary: New York State, Cornell

University, 2011-2015, Large Farms average

= 2.62.

Ohio Farm Business Summary 2011-2015,

Ohio State University Extension, average =

2.55

2011-2015 Northeast Dairy Farm Summary,

Northeast Farm Credit, average =2.98

32

Measure 9

Repayment Schedule:

Scheduled Debt Payment

Competitive Level:

A.

Less than 10% of gross receipts

B.

Less than $400 per cow

Calculation: Example for A:

A.

((Total annual scheduled principal payments $ 158,250 scheduled principal payments

+ total annual scheduled interest payments + $ 52,000 scheduled interest payments

+ total scheduled capital lease payments) + -0- capital lease payments

÷ gross farm receipts) x 100 = $ 210,250 total debt payments

B.

(Total annual scheduled principal payments

÷ $1,450,000 gross farm income

+ total annual scheduled interest payments

+ total scheduled capital lease payments) = 0.145 x 100

÷ number of cows (lactating and dry) = 14.5% of gross receipts

Almost all businesses manage debt.

Scheduled annual debt payments as a

percentage of gross farm receipts is a good

measure of competitiveness. Some debt

can allow a business to take advantage of

opportunities that enhance profitability.

Too many scheduled

principal, interest, and

capital lease payments seriously affect the

ability of a business to meet cash

obligations, have enough left to provide

desired operator income, and reinvest in

the business.

If the operating expense ratio (Measure

3) which measures how much of the

gross farm income is committed to

paying operating expenses is 70%, and

the scheduled debt payment is 10%,

then 80%

o

f

the

farm’s

g

r

oss

inc

o

me

is

c

ommitt

e

d

t

o

pa

y

ing operating

expenses, principal, interest, and capital

lease payments.

This leaves no more than 20% of gross

income available to pay taxes, provide

operator income (sole proprietorships),

operator retirement investment, increase

farm cash reserves, and provide dollars

for reinvestment back into the business or

investment off the farm.

Total scheduled principal and interest

payments used in this calculation do not

typically include

accounts payable within

the next 30 days. Other open accounts that

are kept current even if the payment

is

due in more than 30 days, such as an

annual land rent payment, would also not

be included.

33

However, accounts payable must be

considered if they are open and balances

are building up because the business is

unwilling or unable to pay them. How will

the farm pay these balances?

One option is to commit to paying them

over the next 12 months on a self-imposed

payment plan. The other is to amortize the

accounts payable into one

or more longer-

term notes with scheduled principal and

interest payments. If the farm must follow

this strategy, it can allow the farm to pay a

lower interest rate than is typically

charged on open accounts.

However, this means the farm has

incurred debt for operating expenses,

not debt that helped the farm become

more efficient or productive. The farm

must carefully evaluate how/why it got

into the position of accruing unpaid

balances and determine how it should

change the business to minimize the

possibility of this happening again.

Factors affecting scheduled annual debt

payment:

1.

Total farm debt

2.

How debt is structured (short,

intermediate, or long term)

3.

Interest rates

4.

Gross farm receipts

If the scheduled annual debt payment is

too high:

When scheduled debt payments are too

high and cause difficulties in the farm

business, a manager must first determine

why they are too high and causing

difficulty. Once the cause or causes are

determined, then a farm manager must

explore options and finally take action. If

the business has significant short-term

debt, rescheduling some of that debt over a

longer (but realistic) term will decrease

annual payments.

Review loan terms relative to the asset

purchased. Loan terms should generally

reflect the useful life of the item in the

business. For instance, if a milking parlor

with a projected 15-year useful life is

financed with a 3-year note, cash flow will

be severely compromised. If currently

available interest rates are lower than those

you are paying, refinancing is also an

alternative worth investigating.

Reducing total debt through sale of unused

assets or carefully planning, controlling,

and spreading debt over more cows are also

options. However, any alternative will only

be successful if the business is profitable.

In some cases, when money is borrowed

for an expansion, annual debt payments as

a percentage of gross receipts decreases,

even though total debt increases.

Scheduled debt payments for the high 20%

of farms (based on net return per cow) in

the Ohio Dairy Farm Business Summary

averaged $396 per cow and 5.5% of gross

receipts for 2011 through 2015. The high

10% of all herds in the New York Dairy

Farm Business Summary averaged $388

per cow and 6% of gross receipts for the

same time period. The New York numbers

include the net reduction in operating debt.

34

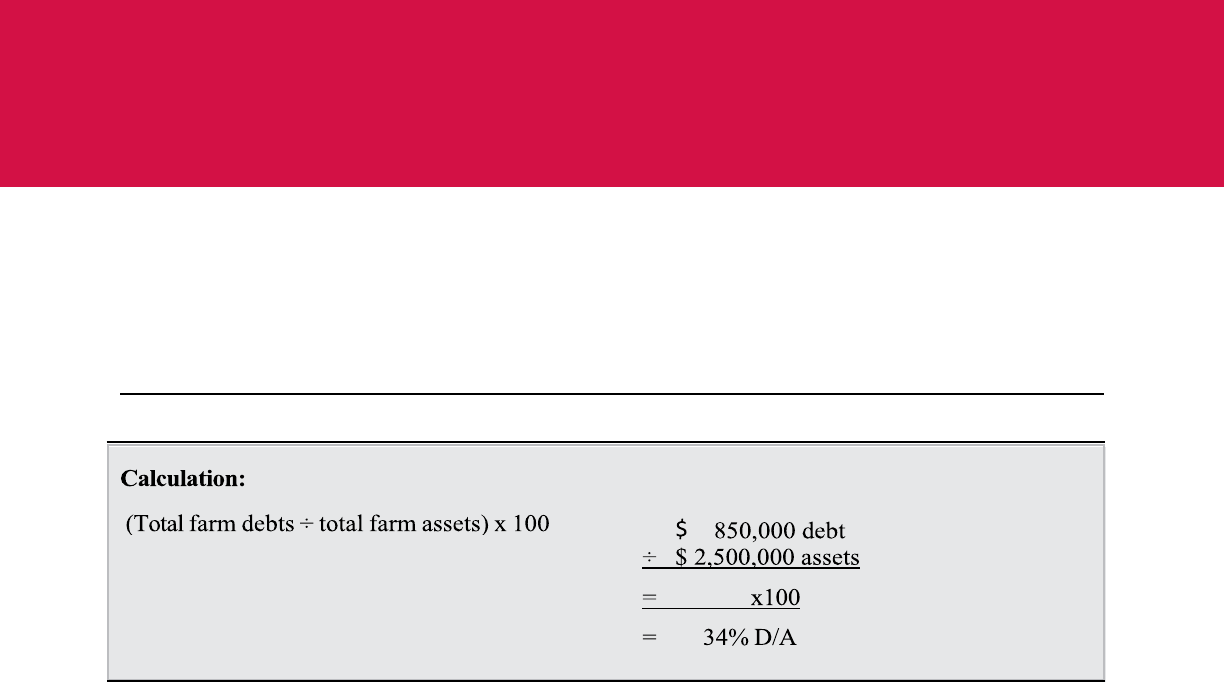

Measure 10

Solvency:

Debt to Asset (D/A) Ratio

Competitive Level:

Less than or equal to 30%

Solvency is a measure of the ability of a

business, at a point in time, to meet all debt

obligations following the sale of all assets.

This is measured by the D/A ratio. The D/A

ratio increases as the business incurs greater

levels of debt and decreases as debt is paid

off. A business with little debt has a D/A ratio

close to zero.

The D/A ratio will vary through the normal

life of a business. Higher ratios are common

in new and expanding businesses — and

often approach financially stressful levels.

Debt levels may reach 60% or more during

some expansions — if and when a lender is

willing to accept that level of risk and work

with the farm. High D/A ratios are acceptable

for limited periods of time when plans and

projections indicate that the profitable

business will quickly generate funds to pay

down debt and bring the ratio back to the

competitive level.

A low D/A ratio is only one indicator of the

financial condition of a business. When

evaluating the

debt position of a business, a

good business manager must also look at the

liquidity of the business, or its ability to meet

cash obligations (Measure 8), and its

profitability (Measures 6 and 7).