PART III

Use of External Debt Statistics

Introduction

1

15.1 The creation of debt is a natural consequence

of economic activity. At any time, some economic

entities have income in excess of their current con-

sumption and investment requirements, while other

entities are deficient in this regard. Through the cre-

ation of debt, both sets of entities are better able to

realize their consumption and output preferences,

thus encouraging economic growth.

15.2 The creation of debt is premised on the as-

sumption that the debtor will meet the requirements

of the debt contract. But if the income of the debtor

is insufficient or there is a lack of sufficient assets to

call upon in the event of income proving insuf-

ficient, debt problems ensue; the stock of debt will

be such that the debtor cannot meet its obligations.

In such circumstances, or in the expectation of such

circumstances, the benefits arising from inter-

national financial flows—for both creditors and

debtors—may not be fully realized. Hence, the need

at the country level for good risk-management pro-

cedures and the maintenance of external debt at sus-

tainable levels.

15.3 This chapter considers tools for sustainability

analysis such as medium-term scenarios and the

role of debt indicators in identifying solvency and

liquidity problems. This is preceded by a short dis-

cussion of the solvency and liquidity aspects of

sustainability.

Solvency

15.4 From a national perspective, solvency can be

defined as the country’s ability to discharge its ex-

ternal obligations on a continuing basis. It is rela-

tively easy, but not very helpful, to define a coun-

try’s theoretical ability to pay. In theory, assuming

debt can be rolled over (renewed) at maturity, coun-

tries are solvent if the present value of net interest

payments does not exceed the present value of other

current account inflows (primarily export receipts)

net of imports.

2

In practice, countries stop servicing

their debt long before this constraint is reached, at

the point where servicing the debt is perceived to

be too costly in terms of the country’s economic

and social objectives. Thus, the relevant constraint

is generally the willingness to pay, rather than the

theoretical macroeconomic ability to pay. To estab-

lish that a country is solvent and willing to pay is

not easy. Solvency is “very much like honesty: it

can never be fully certified, and proofs are slow to

materialize.”

3

15.5 In analyzing solvency problems, it is neces-

sary to take into account the different implications

of public and private sector debt. If there is a risk

that the public sector will cease to discharge its ex-

ternal obligations, this in itself is likely to sharply

curtail financial inflows to all economic sectors

because governments can issue moratoria on debt

repayment and impose exchange restrictions. Siz-

able public external indebtedness may undermine

the government’s commitment to allowing private

sector debt repayment. Also, if private defaults take

place on a significant scale, this too is likely to lead

to a sharp reduction in financial inflows, and gov-

ernment intervention may follow—in the form of

exchange restrictions, a general debt moratorium, or

bailouts. But problems of individual private sector

borrowers may be contained to the concerned

lenders.

15. Debt Sustainability: Medium-Term

Scenarios and Debt Ratios

171

1

This chapter draws on IMF (2000b), Debt- and Reserve-

Related Indicators of External Vulnerability (Washington: March

23, 2000), available on the Internet at http://www.imf.org/external/

np/pdr/debtres/index.htm, as well as work at the World Bank.

2

In considering imports, it is worth noting that these are endoge-

nous and subject to potentially severe compression (reduction).

3

Calvo (1996), p. 208.

External Debt Statistics Guide

Liquidity

15.6 Liquidity problems—that is, when a shortage

of liquid assets affects the ability of an economy to

discharge its immediate external obligations—

almost always emerge in circumstances that give rise

to insolvency or unwillingness to pay. But it is also

possible for a liquidity problem to arise indepen-

dently of a solvency problem, following a self-

fulfilling “run” on a country’s liquidity as creditors

lose confidence and undertake transactions that lead

to pressures on the international reserves of the

economy.

4

Liquidity problems can be triggered, for

example, by a sharp drop in export earnings, or an

increase in interest rates (foreign and/or domestic),

5

or prices for imports. The currency and interest rate

composition of debt, the maturity structure of debt,

and the availability of assets to pay debts are all

important determinants of the vulnerability of an

economy to external liquidity crises; these are all

considered in the next chapter. Mechanisms—such

as creditor “councils”—by which creditors’ actions

can be coordinated can be useful in preventing or

limiting the impact of liquidity crises by sharing in-

formation and coordinating responses.

Medium-Term Debt Scenarios

15.7 External-debt-sustainability analysis is gener-

ally conducted in the context of medium-term sce-

narios. These scenarios are numerical evaluations

that take account of expectations of the behavior of

economic variables and other factors to determine

the conditions under which debt and other indicators

would stabilize at reasonable levels, the major risks

to the economy, and the need and scope for policy

adjustment. Macroeconomic uncertainties, such as

the outlook for the current account, and policy

uncertainties, such as for fiscal policy, tend to domi-

nate the medium-term outlook and feature promi-

nently in the scenarios prepared by the IMF in the

context of Article IV consultations and the design of

IMF-supported adjustment programs.

15.8 The current account balance is important be-

cause, if deficits persist, the country’s external posi-

tion may eventually become unsustainable (as re-

flected by a rising ratio of external debt to GDP). In

other words, financing of continually large current

account deficits by the issuance of debt instruments

will lead to an increasing debt burden, perhaps un-

dermining solvency and leading to external vulnera-

bility from a liquidity perspective, owing to the need

to repay large amounts of debt.

15.9 One advantage of medium-term scenarios is

that borrowing is viewed within the overall macro-

economic framework. However, such an approach

can be very sensitive to projections for variables

such as economic growth, interest and exchange

rates, and, in particular, to the continuation of finan-

cial flows, which are potentially subject to sudden

reversal.

6

Consequently, a range of various alterna-

tive scenarios may be prepared. Also, stress tests—

“what if” scenarios that assume a major change in

one or more variable—can be helpful in analyzing

major risks stemming from fluctuations of these

variables or from changes in other assumptions

including, for example, changes in prices of imports

or exports of oil. Stress tests are useful for liquidity

analysis and provide the basis for developing strate-

gies to mitigate the identified risks, such as enhanc-

ing the liquidity buffer by increasing international

reserves, by establishing contingent credit lines with

foreign lenders, or both.

Debt Ratios

15.10 Debt ratios have been developed mostly to

help indicate potential debt-related risks, and thus to

support sound debt management. Debt indicators in

medium-term scenarios can usefully sum up impor-

tant trends. They are used in the context of medium-

term debt scenarios, as described above, preferably

from a dynamic perspective, rather than as “snap-

shot” measures. Debt ratios should be considered

in conjunction with key economic and financial

variables, in particular expected growth and inter-

est rates, which determine their trend in medium-

term scenarios.

7

Another key factor to consider is

the extent to which there is adequate contract

172

4

For a discussion of self-fulfilling crises, see Krugman (1996)

and Obstfeld (1994).

5

Such as when domestic rates rise because of an economy’s per-

ceived deterioration in creditworthiness.

6

An analysis of key indicators, such as the current account of

the balance of payments, budget deficits, etc., can be particularly

useful in identifying the possibility of reversals in financial flows.

7

If barter trade is significant, and debt payments are in products

that are not easily marketable, this could affect the interpretation

of debt ratios, since the opportunity cost of this form of payment

is different from a purely financial obligation.

15 • Debt Sustainability: Medium-Term Scenarios and Debt Ratios

enforcement—that is, creditor rights, bankruptcy

procedures, etc.—that will help to ensure that private

debt is contracted on a sound basis. More generally,

the incentive structure within which the private sec-

tor operates could affect the soundness of borrowing

and lending decisions; for example, whether there

are incentives that favor short-term or foreign cur-

rency financing.

15.11 As a result, there are conceptual problems in

defining on a general level what are the appropriate

benchmarks for debt ratios; in other words, the scope

for identifying critical ranges for debt indicators is

rather limited. While an analysis over time, in rela-

tion to other macroeconomic variables, might help to

develop a system of early warning signals for a pos-

sible debt crisis or debt-service difficulties, compar-

ing the absolute value of overall debt ratios across

heterogeneous countries is not very useful. For in-

stance, a high or low debt-to-exports ratio in a par-

ticular year may have limited use as an indicator of

external vulnerability; rather, it is the movement of

the debt-to-exports ratio over time that reflects the

debt-related risks.

15.12 For more homogeneous country groupings

and for debt of the public sector, there is more poten-

tial to identify ranges for debt-related indicators that

suggest that debt or debt-service ratios are approach-

ing levels that in other countries have resulted in sus-

pension or renegotiations of debt-service payments,

or have caused official creditors to consider whether

the debt burden may have reached levels that are too

costly to support. For example, assistance under the

HIPC Initiative is determined on the basis of a target

for the ratio of public debt to exports (150 percent),

or the ratio of debt to fiscal revenue (250 percent). In

these ratios, the present value of debt is used, and

only a subset of external debt is taken into consider-

ation, namely medium- and long-term public and

publicly guaranteed debt.

8

15.13 Several widely used debt ratios are discussed

in somewhat greater detail later. Table 15.1 provides

a more comprehensive list. Broadly speaking, there

are two sets of debt indicators: those based on flow

variables (for example, related to exports or GDP)—

these are called flow indicators because the numera-

tor or denominator or both are flow variables; and

those based on stock variables—that is, both numer-

ator and denominator are stock variables.

Ratio of Debt to Exports and Ratio

of Present Value of Debt to Exports

15.14 The debt-to-exports ratio is defined as the

ratio of total outstanding debt at the end of the year

to the economy’s exports of goods and services for

any one year. This ratio can be used as a measure of

sustainability because an increasing debt-to-exports

ratio over time, for a given interest rate, implies that

total debt is growing faster than the economy’s basic

source of external income, indicating that the coun-

try may have problems meeting its debt obligations

in the future.

15.15 Indicators that use the stock of debt have sev-

eral shortcomings in common. First, countries that

use external borrowing for productive investment

with long gestation periods are more likely to exhibit

high debt-to-exports ratios. But as the investments

begin to produce goods that can be exported, the

country’s debt-to-exports ratio may start to decline.

So for these countries, the debt-to-exports ratio may

not be too high from an intertemporal perspective

even if in any given year it may be perceived as

large. Therefore, arguably this indicator can be

based on exports after the average gestation lag—

that is, using projected exports one or several time

periods ahead as a denominator.

9

More generally,

this also highlights the need to monitor debt indica-

tors in medium-term scenarios to overcome the limi-

tations of a “snapshot.”

15.16 Second, some countries may benefit from

highly concessional debt terms, while others pay

high interest rates. For such countries, to better cap-

ture the implied debt burden—in terms of the oppor-

tunity cost of capital—it is useful to report and ana-

lyze the average interest rate on debt or to calculate

the present value of debt by discounting the pro-

jected stream of future amortization payments in-

cluding interest, with a risk-neutral commercial ref-

erence rate. As noted above, in analyzing debt

173

8

See Andrews and others (1999); available on the Internet at

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/cat/longres.cfm?sk=3448.0.

Appendix V discusses the HIPC approach and includes informa-

tion on the debt ratios monitored.

9

To average out idiosyncratic or irregular swings in export per-

formance, multiyear period averages are frequently used, such as

the three-year averages used in the debt-sustainability analysis for

HIPCs.

External Debt Statistics Guide

sustainability for HIPCs, the IMF and World Bank

use such a present value of debt measure—notably

present value of debt to exports, and to fiscal rev-

enue (see below). A high and rising present value of

the debt-to-exports ratio is considered to be a sign

that the country is on an unsustainable debt path.

Ratio of Debt to GDP and Ratio

of Present Value of Debt to GDP

15.17 The debt-to-GDP ratio is defined as the ratio

of the total outstanding external debt at the end of

the year to annual GDP. By using GDP as a denomi-

174

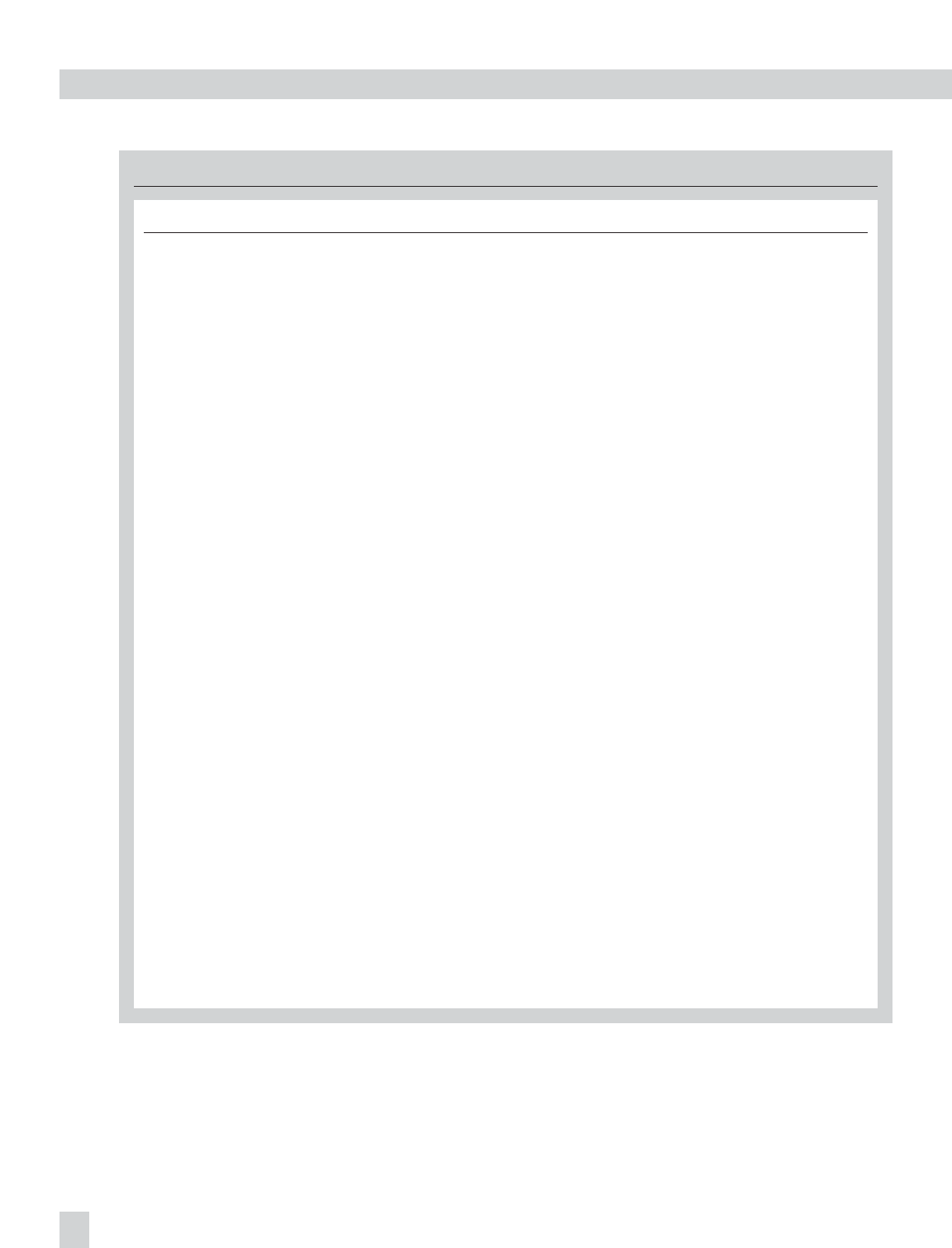

Ta b le 15.1. Overview of Debt Indicators

Indicator Evaluation/Use

Solvency

Interest service ratio Ratio of average interest payments to export earnings indicates terms of external

indebtedness and thus the debt burden

External debt to exports Useful as trend indicator closely related to the repayment capacity of a country

External debt over GDP Useful because relates debt to resource base (for the potential of shifting production

to exports so as to enhance repayment capacity)

Present value of debt over exports Key sustainability indicator used, for example, in HIPC Initiative assessments

comparing debt burden with repayment capacity

Present value of debt over fiscal revenue Key sustainability indicator used, for example, in HIPC Initiative assessments

comparing debt burden with public resources for repayment

Debt service over exports Hybrid indicator of solvency and liquidity concerns

Liquidity

International reserves to short-term debt Single most important indicator of reserve adequacy in countries with significant but

uncertain access to capital markets; ratio can be predicted forward to assess

future vulnerability to liquidity crises

Ratio of short-term debt to total Indicates relative reliance on short-term financing; together with indicators of

outstanding debt maturity structure allows monitoring of future repayment risk

Public sector indicators

Public sector debt service over exports Useful indicator of willingness to pay and transfer risk

Public debt over GDP or tax revenues Solvency indicator of public sector; can be defined for total debt or for external debt

Average maturity of nonconcessional debt Measure of maturity that is not biased by long repayment terms for concessional

debt

Foreign currency debt over total debt Foreign currency debt including foreign currency indexed debt; indicator of the

impact of a change in the exchange rate on debt

Financial sector indicators

Open foreign exchange position Foreign currency assets minus liabilities plus net long positions in foreign currency

stemming from off-balance-sheet items; indicator for foreign exchange risk, but

normally small because of banking regulations

Foreign currency maturity mismatch Foreign currency liabilities minus foreign currency assets as percent of these foreign

currency assets at given maturities; indicator for pressure on central bank reserves

in case of a cutoff of financial sector from foreign currency funding

Gross foreign currency liabilities Useful to the extent that assets are not usable to offset withdrawals in liquidity

Corporate sector indicators

Leverage Nominal (book) value of debt over equity (assets minus debt and derivatives

liabilities); key indicator of sound financial structure; high leverage aggravates

vulnerability to other risks (for example, low profitability, high ratio of short-term

debt/total debt)

Interest over cash flow Total prospective interest payments over operational cash flow (before interest and

taxes); key cash flow indicator for general financial soundness

Short-term debt over total term debt In combination with leverage, indicator of vulnerability to temporary cutoff from

(both total and for foreign currency only) financing

Return on assets (before tax and interest) Profit before tax and interest payments over total assets; indicator of general

profitability

Net foreign currency cash flow over total Net foreign currency cash flow is defined as prospective cash inflows in foreign

cash flow currency minus prospective cash outflows in foreign currency; key indicator for

unhedged foreign currency exposure

Net foreign currency debt over equity Net foreign currency debt is defined as the difference between foreign currency debt

liabilities and assets; equity is assets minus debt and net derivatives liabilities;

indicator for balance sheet effect of exchange rate changes

15 • Debt Sustainability: Medium-Term Scenarios and Debt Ratios

nator, the ratio may provide some indication of the

potential to service external debt by switching re-

sources from production of domestic goods to the

production of exports. Indeed, a country might have

a large debt-to-exports ratio but a low debt-to-GDP

ratio if exportables comprise a very small proportion

of GDP.

15.18 While the debt-to-GDP ratio is immune from

export-related criticisms that mainly focus on the

differing degree of value added in exports and price

volatility of exports, it may be less reliable in the

presence of over- or undervaluations of the real ex-

change rate, which could significantly distort the

GDP denominator. Also, as with the debt-to-exports

ratio, it is important to take account of the country’s

stage of development and the mix of concessional

and nonconcessional debt.

15.19 In the context of debt ratios, the numerator in

the present value of debt-to-GDP ratio is again esti-

mated using future projections of debt-service pay-

ments discounted by market-based interest rates

(that is, a risk-neutral commercial reference rate).

Ratio of Present Value of Debt

to Fiscal Revenue

15.20 The ratio of the present value of debt to fiscal

revenue is defined as the ratio of future projected

debt-service payments discounted by market-based

interest rates (a risk-neutral commercial reference

rate) to annual fiscal revenue. This ratio can be used

as a measure of sustainability in those countries with

a relatively open economy facing a heavy fiscal bur-

den of external debt. In such circumstances, the gov-

ernment’s ability to mobilize domestic revenue is

relevant and will not be measured by the debt-to-

exports or debt-to-GDP ratios. An increase in this

indicator over time indicates that the country may

have budgetary problems in servicing its debt.

Ratio of Debt Service to Exports

10

15.21 This ratio is defined as the ratio of external

debt-service payments of principal and interest on

long-term and short-term debt to exports of goods

and services for any one year. The debt-service-to-

exports ratio is a possible indicator of debt sustain-

ability because it indicates how much of a country’s

export revenue will be used up in servicing its debt

and thus, also, how vulnerable the payment of debt-

service obligations is to an unexpected fall in export

proceeds. This ratio tends to highlight countries with

significant short-term external debt. A sustainable

level is determined by the debt-to-exports ratio and

interest rates, as well as by the term structure of debt

obligations. The latter may affect creditworthiness

because the higher the share of short-term credit is in

overall debt, the larger and more vulnerable is the

annual flow of debt-service obligations.

15.22 By focusing on payments, the debt-service-

to-exports ratio takes into account the mix of conces-

sional and nonconcessional debt, while its evolution

over time, especially in medium-term scenarios, can

provide useful information on lumpy repayment

structures. Moreover, a narrow version of the debt-

service ratio, focused on government and govern-

ment-guaranteed debt service, can be a useful indi-

cator of government debt sustainability and transfer

risk (the risk that exchange rate restrictions are im-

posed that prevent the repayment of obligations) be-

cause it may provide some insight into the political

cost of servicing debt.

11

15.23 The debt-service-to-exports ratio has some

limitations as a measure of external vulnerability, in

addition to the possible variability of debt-service

payments and export revenues from year to year.

First, amortization payments on short-term debt are

typically excluded from debt service,

12

and the cov-

erage of private sector data can often be limited, ei-

ther because the indicator is intentionally focused on

the public sector or because data on private debt ser-

vice are not available.

15.24 Second, many economies have liberalized

their trade regimes and are now exporting a larger

proportion of their output to the rest of the world.

But at the same time they are importing more, and

175

10

This ratio, in addition to the total debt-to-exports and the total

debt-to-GNP (national output) ratios, is provided for individual

countries in the World Bank’s annual Global Development

Finance publication.

11

A version of this indicator that focuses on official debt is used,

for instance, in the HIPC Initiative.

12

This is the approach taken in the World Bank’s World Devel-

opment Report and Global Development Finance, and the IMF’s

World Economic Outlook. Lack of data, as well as the assumption

that short-term debt mainly constituted trade credit that was easy

to roll over, contributed to this practice. As experience shows, this

assumption is in some cases questionable.

External Debt Statistics Guide

the import content of exports is rising. Thus, a debt-

service-to-exports ratio not corrected for the import

intensity of exports is biased downward for econo-

mies with a higher propensity to export;

13

this argu-

ment applies similarly to the debt-to-exports ratio.

15.25 Finally, the concept summarizes both liquid-

ity and solvency issues, which may make it analyti-

cally less tractable than measures that track only sol-

vency (such as the ratio of interest payments to

exports) or liquidity (the ratio of reserves to short-

term debt).

Ratio of International Reserves

to Short-Term Debt

15.26 This ratio is a pure liquidity indicator that is

defined as the ratio of the stock of international re-

serves available to the monetary authorities to the

short-term debt stock on a remaining-maturity basis.

This could be a particularly useful indicator of re-

serve adequacy, especially for countries with signifi-

cant, but not fully certain, access to international

capital markets.

14

15.27 The ratio indicates whether international re-

serves exceed scheduled amortization of short-,

medium-, and long-term external debt during the fol-

lowing year; that is, the extent to which the economy

has the ability to meet all its scheduled amortizations

to nonresidents for the coming year using its own in-

ternational reserves. It provides a measure of how

quickly a country would be forced to adjust if it were

cut off from external borrowing—for example,

because of adverse developments in international

capital markets. All scheduled debt amortization

payments on both private and public debt to nonresi-

dents over the coming year are covered in such a

ratio under short-term debt, regardless of the instru-

ment or currency denomination. A similar ratio can

be calculated focusing on the foreign currency debt

of the government (and banking sector) only. This

may be especially relevant for economies with very

open capital markets, and significant public sector

foreign currency debt.

15.28 Interestingly, in most theoretical models the

maturity structure of public debt is irrelevant be-

cause it is assumed that markets are complete.

15

But

markets are rarely complete, even in developed

countries. And, as several currency crises in develop-

ing and emerging market countries in the mid-to-late

1990s have shown, the risk associated with an exces-

sive buildup of the stock of short-term debt relative

to international reserves can be quite severe, even in

countries that were generally regarded as solvent.

One conclusion drawn has been that countries with

excessively large short-term debt in relation to inter-

national reserves are more susceptible to liquidity

crisis.

16

15.29 However, various factors need to be taken

into account when interpreting the ratio of interna-

tional reserves to short-term debt. First, a large stock

of short-term debt relative to international reserves

does not necessarily lead to a crisis. Many advanced

economies have higher ratios of short-term debt to

reserves than many emerging economies, which

have shown vulnerability to financial crisis. Factors

such as an incentive structure that is conducive to

sound risk management, and a proven track record

of contract enforcement, can help develop credibil-

ity, and help to explain this difference. Moreover,

macroeconomic fundamentals, in particular the cur-

rent account deficit and the real exchange rate, play

an important role. Consideration should also be

given to the exchange rate regime. For example, a

flexible regime can reduce the likelihood and costs

of a crisis. Finally, the ratio assumes that measured

international reserves are indeed available and can

be used to meet external obligations; this has not al-

ways been true historically.

176

13

See Kiguel (1999) for more reasons why the ratio of debt ser-

vice to exports may not be a highly reliable indicator of the exter-

nal vulnerability of a country under special circumstances.

14

The potential importance of other residents’ external assets in

relation to debt is highlighted in the table for the net external debt

position presented in Chapter 7 (Table 7.11).

15

See Lucas and Stokey (1983) and Calvo and Guidotti (1992).

16

See Berg and others (1999); Bussière and Mulder (1999); and

Furman and Stiglitz (1998).

Introduction

16.1 The type of debt ratios discussed in the pre-

vious chapter focus primarily on overall external

debt and external debt service and the potential to

meet debt obligations falling due on an economy-

wide basis. However, in assessing the vulnerability

of the economy to solvency and liquidity risk aris-

ing from the external debt position, a more detailed

examination of the composition of the external debt

position and related activity may be required. In this

chapter, the relevance of additional data on the com-

position of external debt, external income, external

assets, financial derivatives, and on the economy’s

creditors is explored, drawing particularly on data

series described in Part I of the Guide. The discus-

sion in this chapter, however, is not intended to be

exhaustive.

Composition of External Debt

16.2 The relevance for debt analysis of the different

data series presented in the Guide is set out below. In

particular this section focuses on the following

issues:

•Who is borrowing?

• What is the composition of debt by functional

category?

• What type of instrument is being used to borrow?

• What is the maturity of debt?

• What is the currency composition of the debt?

• Is there industrial concentration of debt?

• What is the profile of debt servicing?

16.3 Traditionally in debt analysis, the focus has

been on official sector borrowing, not least in the

form of loans from banks or official sources. But the

1990s saw a tremendous expansion in capital market

borrowing by the private sector. This has had signifi-

cant implications for debt analysis, including the

need to gather and analyze external debt data by the

borrowing sector.

16.4 If there is a risk that the public sector will

cease to discharge its external obligations, this is

likely in itself to lead to a sharp curtailment of finan-

cial inflows to the economy as a whole, in part be-

cause it also casts severe doubt on the government’s

commitment to an economic environment that al-

lows private sector debt repayment. Thus, informa-

tion on public sector total, and short-term, external

debt is important. Especially in the absence of capi-

tal controls or captive markets, information on short-

term domestic debt of the government is important,

since capital flight and pressure on international re-

serves can result from a perceived weak financial

position of the public sector.

16.5 Also, beyond its own borrowing policies, the

government has a special role to play in ensuring

that it creates or maintains conditions for sound risk

management in other sectors; for instance, avoiding

policies that create a bias toward short-term foreign

currency borrowing.

16.6 Most of the financial sector, notably banks,is

by nature highly leveraged—that is, most assets

are financed by debt liabilities. Banks may take on

liabilities to nonresidents by taking deposits

and short-term interbank loans. These positions

can build up quickly and, depending also on the

nature of the deposits and depositors, be run down

quickly. How well banks intermediate these funds

has implications for the ability to withstand large-

scale withdrawals. More generally, information

on the composition of assets and liabilities is impor-

tant for banks (and nonbank financial cor-

porations)—notably information on the maturity

structure and maturity mismatch (including in

foreign currency)—because it provides insight

about their vulnerability to such withdrawals and

16. External Debt Analysis: Further

Considerations

177

External Debt Statistics Guide

their sensitivity to changing exchange and interest

rates.

1

16.7 As mentioned in Chapter 15, large-scale defaults

by nonfinancial corporations that borrow from

abroad, depending on their importance to the econ-

omy, could result in financially expensive government

intervention, an impact on the credit risk of the finan-

cial sector, and an undermining of asset prices in the

economy. In any case, the debt-service needs of cor-

porations will affect the economy’s liquidity situation.

As with banks, the regulatory regime and incentive

structure within which the corporate sector operates is

important. For instance, overborrowing in foreign

currency, particularly short-term, in relation to for-

eign currency assets or hedges (be they natural hedges

in the form of foreign currency cash flow or through

derivatives products such as forwards), exposes the

corporate sector to cash-flow (liquidity) problems in

case of large exchange rate movements. Overborrow-

ing in foreign currency in relation to foreign currency

assets could potentially expose corporations to sol-

vency problems in the event of a depreciation of the

domestic exchange rate. Ensuing corporate failures,

in the event of sharp exchange rate depreciation, can

reduce external financing flows and depress domestic

activity, especially if contract enforcement is poor or

the procedures are overwhelmed.

16.8 The provision of guarantees can influence eco-

nomic behavior. Invariably, the government provides

implicit and explicit guarantees, such as deposit insur-

ance, and sometimes also guarantees on private sector

external borrowing (classified as publicly guaranteed

private sector debt in the Guide). Also, domestic cor-

porations may use offshore enterprises to borrow, and

provide guarantees to them, or have debt payments

guaranteed by domestic banks. Similarly foreign cor-

porations may guarantee part of domestic debt. Where

possible, direct and explicit guarantees should be

monitored because they affect risk assessment.

16.9 The functional classification of debt instru-

ments is a balance of payments concept, grouping

instruments into four categories: direct investment,

portfolio investment, financial derivatives, and other

investment. Direct investment takes place between

an investor in one country and its affiliate in another

country and is generally based on a long-term rela-

tionship. Recent crises have tended to support the

view that this category of investment is less likely to

be affected in a crisis than other functional types.

2

Portfolio investment, by definition, includes tradable

debt instruments; other investment, by definition, in-

cludes all other debt instruments. The relevance of

financial derivatives instruments for external debt

analysis is discussed below.

16.10 The type of instrument that a debtor will

issue depends on what creditors are willing to pur-

chase as well as the debtor’s preferences. Borrowing

in the form of loans concentrates debt issuance in the

hands of banks, whereas securities are more likely to

be owned by a wider range of investors. Trade credit

is typically of a short-term maturity. Although equity

issues are not regarded as debt instruments, declared

dividends on equity are included in debt servicing,

and so it remains necessary to monitor activity in

these instruments. At the least, sudden sales of eq-

uity by nonresidents or residents can have important

ramifications for an economy and its ability to raise

and service debt.

3

16.11 The maturity composition of debt is impor-

tant because it can have a profound impact on liquid-

ity. Concentration of high levels of short-term exter-

nal debt is seen to make an economy particularly

vulnerable to unexpected downturns in financial

fortune.

4

For instance, an economy with high levels

of short-term external debt may be vulnerable to a

sudden change in investor sentiment. Interbank lines

are particularly sensitive to changes in risk per-

ception, and early warning signals of changes in

investor sentiment towards the economy might be

178

1

Banks are subject to moral hazard risk through explicit or im-

plicit deposit insurance and limited liability. The potential moral

hazard risk arising from deposit insurance schemes is that by “pro-

tecting” from loss an element of their deposit base, banks might be

provided with an incentive to hold portfolios incorporating more

risk, but potentially higher returns, than they otherwise would.

Monitoring the risks taken by banks is a central element of banking

supervision, a subject beyond the scope of the Guide.

2

However, direct investment enterprises may place additional

pressure on the exchange rate in a crisis situation through the

hedging of domestic currency assets. Moreover, foreign investors

can repatriate rather than reinvest profits, thereby effectively in-

creasing the domestically (debt) funded part of their investments.

3

In analyzing the securities transactions, both debt and equity,

changes in prices (rather than in quantities) may equilibrate the

market.

4

The compilation of average maturity data might disguise

important differences in the sectoral composition of debt and in the

dispersion of maturities. However, data on average maturity by

sector and by debt instrument might alert policymakers and market

participants to maturity structures that are potentially problematic.

16 • External Debt Analysis: Further Considerations

detected through the monitoring of the refinancing

(“rollover”) rate.

5

16.12 Debt analysis needs to make a distinction

between short-term debt on an original maturity

basis—that is, debt issued with a maturity of one

year or less—and on a remaining-maturity basis—

that is, debt obligations that fall due in one year or

less. Data on an original maturity basis provides

information on the typical terms of debt and the debt

structure, and monitoring changes in these terms

provides useful information on the preferences of

creditors and the sectoral distribution of debtors.

Data on a remaining (residual) maturity basis pro-

vides the analyst and policymaker with information

on the repayment obligations (that is, the liquidity

structure). For the policymaker, to ensure sufficient

liquidity, such as indicated by an appropriate ratio of

international reserves to short-term debt, requires

avoiding a bunching of debt payments.

16.13 The debtor will be interested in the nominal

value of its debt because at any moment in time it is

the amount that the debtor owes to the creditor at that

moment. Also, the debtor is well advised to monitor

the market value of its debt. The market value and

the spreads over interest rates on “risk-free” instru-

ments provide an indication to the borrower of the

market view on its ability to meet debt obligations as

well as current market sentiment toward it.

6

This is

important information because it might influence fu-

ture borrowing plans: whether it is advantageous to

borrow again while terms seem good, or whether

there are early warning signs of possible increased

costs of borrowing, or even refinancing difficulties.

However, for those countries with debt that has a very

low valuation or is traded in markets with low liquid-

ity (or both), a sudden swing in sentiment might cause

a very sharp change in the market value of external

debt, which might also be reversed suddenly. Because

it would be unaffected by such swings, information

on the nominal value of external debt would be of

particular analytical value in such circumstances.

16.14 The currency composition of external debt is

also important. There is a significant difference be-

tween having external debt payable in domestic cur-

rency and having external debt payable in foreign

currency. In the event of a sudden depreciation of the

domestic currency, foreign currency external debt

(including foreign-currency-linked debt) has poten-

tially important wealth and cash-flow effects for the

economy. For instance, when public debt is payable

in foreign currency, a devaluation of the domestic

currency could aggravate the financial position of the

public sector, so creating an incentive for the govern-

ment to avoid a necessary exchange rate adjustment.

Information on the currency composition of debt at

the sectoral level, including resident and nonresident

claims in foreign currency, is particularly important

because the wealth effects also depend on foreign

currency relations between residents.

16.15 But any analysis of the foreign currency com-

position of external debt needs to take account of the

size and composition of foreign currency assets, and

income, together with foreign-currency-linked finan-

cial derivatives positions. The latter instruments can

be used to change the exposure from foreign to do-

mestic currency or to a different foreign currency.

16.16 The interest rate composition of external

debt, both short- and long-term, may also have signifi-

cant implications. Sharp increases in short-term inter-

est rates, such as those experienced in the early 1980s,

can have profound implications for the real cost of

debt, especially if a significant share of debt pays

interest that is linked to a floating rate such as LIBOR.

As with the foreign currency position, it is necessary

to take account of financial derivatives positions, since

these may significantly change the effective interest

composition of debt. For instance, interest-rate-based

financial derivatives can be used to swap variable-rate

obligations into fixed-rate liabilities, and vice versa.

The relevance of financial derivatives in analyzing ex-

ternal debt is considered in more detail below.

16.17 The industrial concentration of debt should

also be monitored. If debt is concentrated in a partic-

ular industry or industries, economic shocks such as

a downturn in worldwide demand for certain prod-

ucts could increase the risk of a disruption in debt-

service payments by that economy.

7

179

5

This type of monitoring is discussed in more detail in Chapter

7, Box 7.1.

6

Increasingly, information from credit derivatives, such as de-

fault swaps and spread options, also provides market information

on an entity’s credit standing.

7

While the Guide does not explicitly include guidance for the

measurement of the industrial composition of external debt, these

data can be compiled using the concepts set out in the Guide to-

gether with the International Standard Industrial Classification

(1993 SNA, pp. 594–96) as the “sector” classification.

External Debt Statistics Guide

16.18 To monitor debt service, the amounts to be

paid are important, rather than the market value of

the debt. Debt servicing involves both the ongoing

meeting of obligations—that is, payments of interest

and principal—and the final payment of principal at

maturity. However, it is most unlikely that the debt-

service schedule will be known with certainty at any

given time. Estimates of the amounts to be paid can

vary over time because of variable interest and for-

eign currency rates, and the repayment dates for debt

containing embedded put (right to sell) or call (right

to buy) options that can be triggered under certain

conditions add further uncertainty. So, in presenting

data on the debt-service payment schedule, it is im-

portant that the assumptions used to estimate future

payments on external debt liabilities be presented in

a transparent manner along with the data.

16.19 One indication of an economy that is begin-

ning to have difficulty servicing its external debt is

when the level of arrears is on a rising trend both in

relation to the external debt position and to the

amount of debt service falling due. In such circum-

stances, detailed data by institutional sector and by

type of instrument might help to identify the sources

of the difficulty.

The Role of Income

16.20 In analyzing debt, the future trend of income

is clearly relevant because it affects the ability of the

debtor to service debt. Traditionally, the focus has

been on earnings from exports of goods and ser-

vices. To what extent is debt, or are debt-service

payments, “covered” by earnings from the export of

goods and services? Diversification of products and

markets is positive because it limits exposure to

shocks, in turn limiting the possibility that the pri-

vate sector as a whole will get into difficulties, and

that the public sector will lose revenues, thus affect-

ing the willingness to pay. The currency composition

of export earnings may also be of relevance.

16.21 While the willingness to pay is an important

factor in determining whether debt-service payments

are made, the use of external borrowing will affect

the future income from which those payments are

made.

8

If debt is used to fund unproductive activity,

future income is more likely to fall short of that

required to service the debt. The question to address

is not so much the specific use of the borrowed

capital but rather the efficiency of total investment in

the economy, considered in the context of indicators

for the economy as a whole, such as the growth rates

of output and exports, and total factor productivity—

all data series potentially derivable from national

accounts data. From another perspective, if an econ-

omy is unwilling to service its debts, and defaults,

production losses might ensue as the economy

ceases to be integrated with international capital

markets.

The Role of Assets

16.22 As indicated above, the external debt position

needs to be considered in the context of external as-

sets because these help to meet debt-servicing re-

quirements—assets generate income and can be sold

to meet liquidity demands. In the IIP, the difference

between external assets and external liabilities is the

net asset (or liability) position of an economy.

16.23 For all economies, international reserve

assets are, by definition, composed of external

assets that are readily available to and controlled by

the monetary authorities for direct financing of pay-

ments imbalances, for indirectly regulating the

magnitude of such imbalances through intervention

in exchange markets to affect the currency exchange

rate, and for other purposes. Because of this role, in

March 1999, the IMF’s Executive Board, drawing

on the work of the IMF and the Committee on

Global Financial Systems of the G-10 central banks,

strengthened the Special Data Dissemination Stan-

dard requirements for the dissemination of data on

international reserves, and foreign currency liquid-

ity. A data template on international reserves and

foreign currency liquidity was introduced that pro-

vides a considerably greater degree of transparency

in international reserves data than was hitherto

available.

9

180

8

Dragoslav Avramovic and others (1964, p. 67) noted that while

the debt-service ratio “does serve as a convenient yardstick for

passing short-term creditworthiness judgments, that is to say,

judgments of the risk that default may be provoked by liquidity

crises,” in fact “the only important factor, from the long-run point

of view, is the rate of growth of production.” Indeed, “it is only in

the interest of the borrowers as well as of the lenders that output

and savings be maximized, since they are the only real source

from which debt service is paid.”

9

See Kester (2001).

16 • External Debt Analysis: Further Considerations

16.24 But as private entities in an economy become

increasingly active in international markets, they

are likely to acquire external assets as well as lia-

bilities. The diverse nature of private sector external

assets suggests that they are of a different nature

than reserve assets. For instance, private sector

external assets may not be distributed among sec-

tors and individual enterprises in such a way that

they can be used to absorb private sector liquidity

needs. But the presence of such assets needs to be

taken into account in individual country analysis of

the external debt position. One approach is to pre-

sent the net external debt position for each institu-

tional sector, thus comparing the institutional attri-

bution and concentration of external assets in the

form of debt instruments with external debt (see

Chapter 7).

16.25 But in comparing assets with debt, it is neces-

sary to also consider the liquidity and quality of as-

sets, their riskiness, and the functional and instru-

ment composition of assets.

16.26 Most important, assets should be capable of

generating income or be liquid so that they could be

sold if need be, or both. The functional compo-

sition of assets provides important information

in this regard. For instance, direct investment assets

may generate income but are often less liquid,

especially if they take the form of fully owned non-

traded investments in companies or subsidiaries.

Typically, direct investment assets are either illiquid

in the short term (such as plant and equipment) or,

if they are potentially marketable, the direct in-

vestor needs to take into account the implications

on direct investment enterprises of withdrawing

assets. The latter will be a countervailing factor to

any selling pressures. Nonetheless, some direct

investment assets may be closer to portfolio invest-

ments and relatively tradable—such as nonmajority

shares in companies in countries with deep equity

markets.

16.27 Portfolio investment is by definition tradable.

Investments—such as loans and trade credit—while

generating income can be less liquid than portfolio

investment, but the maturity of these investments

may be important because the value of short-term

assets can be realized early. Increasingly, loans can

be packaged into a single debt instrument and

traded. Trade credit may be difficult to withdraw

without harming export earnings, a very impor-

tant source of income during situations of external

stress.

16.28 In assessing assets in the context of debt

analysis, the quality of assets is a key factor. In prin-

ciple the quality of the assets is reflected in the price

of the assets. Some knowledge of the issuer and the

country of residence may provide a further idea of

the quality of the asset and its availability in times of

a crisis; availability is often correlated with location

or type of country. Knowledge of the geographic

spread of assets can help one to understand the vul-

nerability of the domestic economy to financial diffi-

culties in other economies.

16.29 The currency composition of assets, to-

gether with that of debt instruments, provides an

idea of the impact on the economy of changes in the

various exchange rates; notably, it provides informa-

tion on the wealth effect of cross exchange rate

movements (such as changes in the dollar-yen

exchange rate for euro-area countries). The BIS

International Banking Statistics (see next chapter),

and the IMF’s Coordinated Portfolio Investment

Survey (see Chapter 13), at the least, encourage the

collection of data on the country of residence of the

nonresident debtor, and the currency composition of

assets.

Relevance of Financial Derivatives and

Repurchase Agreements (Repos)

16.30 The growth in financial derivatives markets

has implications for debt management and analysis.

They are used for a number of purposes including

risk management, hedging, arbitrage between mar-

kets, and speculation.

16.31 From the viewpoint of managing the risks

arising from debt instruments, derivatives can be

both cheaper and more efficient than other tools.

This is because they can be used to directly trade

away the specific risk to be managed. For instance, a

foreign currency borrowing can be hedged through a

foreign-currency-linked derivative and so eliminate

part or all of the foreign currency risk. Thus, aggre-

gate information on the notional position in foreign

currency derivatives is important in determining the

wealth and cash-flow effects of changing exchange

rates. Similarly, the cash-flow uncertainties involved

in borrowing in variable interest rates can be reduced

181

External Debt Statistics Guide

by swapping into “fixed-rate” payments with an in-

terest rate swap.

10

In both instances the derivatives

contract will involve the borrower in additional

counterparty credit risk, but it facilitates good risk-

management practices.

16.32 Derivatives are also used as speculative and

arbitrage instruments.

11

They are a tool for undertak-

ing leveraged transactions, in that for relatively little

capital advanced up front, significant exposures to

risk can be achieved, and differences in the implicit

price of risk across instruments issued by the same

issuer, or very similar issuers, can be arbitraged.

12

However, if used inappropriately, financial deriva-

tives can cause significant losses and so enhance the

vulnerability of an economy. Derivatives can also be

used to circumvent regulations, and so place unex-

pected pressure on markets. For instance, a ban on

holding securities can be circumvented by foreign

institutions through a total-return swap.

13

16.33 Derivatives positions can become very valu-

able or costly depending on the underlying price

movements. The value of the positions is measured

by the market value of the positions. For all the

above reasons, there is interest in market values,

gross assets and liabilities, and notional (or nominal)

values of financial derivatives positions.

14

16.34 Risk-enhancing or -mitigating features that

are similar to financial derivatives may also be em-

bedded in other instruments such as bonds and notes.

Structured bonds are an example of such enhanced

instruments. These instruments could, for example,

be issued in dollars, with the repayment value de-

pendent on a multiple of the Mexican peso–U.S. dol-

lar exchange rate. Borrowers may also include a

put—right to sell—option in the bond contract that

might lower the coupon rate but increase the likeli-

hood of an early redemption of the bond, not least

when the borrower runs into problems. Also, for

example, credit-linked bonds may be issued that

include a credit derivative, which links payments of

interest and principal to the credit standing of an-

other borrower. The inclusion of these derivatives

can improve the terms that the borrower would oth-

erwise have received, but at the cost of taking on

additional risk. Uncertainty over the repayment

terms or the repayment schedule is a consequence,

so there is analytical interest in information on these

structured bond issues.

16.35 Repurchase agreements (repos) also facili-

tate improved risk management and arbitrage. A

repo allows an investor to purchase a financial in-

strument, and then largely finance this purchase by

on-selling the security under a repo agreement. By

selling the security under a repo, the investor retains

exposure to the price movements of the security,

while requiring only modest cash outlays. In this ex-

ample, the investor is taking a “long” or positive po-

sition. On the other hand, through a security loan,a

speculator or arbitrageur can take a “short” or nega-

tive position in an instrument by selling a security

they do not own and then meeting their settlement

needs by borrowing the security (security loan) from

another investor.

16.36 While in normal times all these activities add

liquidity to markets and allow the efficient taking of

positions, when sentiment changes volatility may in-

crease as leveraged positions may need to be un-

wound, such as the need to meet margin require-

ments. Position data on securities issued by residents

and involved in repurchase and security lending

transactions between residents and nonresidents help

in understanding and anticipating market pressures.

These data can also help in understanding the debt-

service schedule data. For example, if a nonresident

sold a security under a repo transaction to a resident

who then sold it outright to another nonresident, the

debt-service schedule would record two sets of pay-

ments to nonresidents by the issuer for the same se-

curity, although there would be one set of payments

for the one security. In volatile times, when large po-

sitions develop in one direction, this might result in

182

10

The risk might not be completely eliminated if at the reset of

the floating rate the credit risk premium of the borrower changes.

The interest rate swap will eliminate the risk of changes in the

market rate of interest.

11

Speculation and arbitrage activity can help add liquidity to

markets and facilitate hedging. Also, when used for arbitrage pur-

poses, derivatives may reduce any inefficient pricing differentials

between markets and/or instruments.

12

Leverage, as a financial term, describes having the full bene-

fits arising from holding a position in a financial asset without

having had to fund the purchase with own funds. Financial deriva-

tives are instruments that can be used by international investors to

leverage investments, as are repos.

13

A total-return swap is a credit derivative that swaps the total

return on a financial instrument for a guaranteed interest rate, such

as an interbank rate, plus a margin.

14

While the Guide explicitly presents data only on the notional

(or nominal) value for foreign-currency- and interest-rate-linked

financial derivatives, information on the notional value of finan-

cial derivatives, for all types of risk category, by type and in aggre-

gate, can be of analytical value.

16 • External Debt Analysis: Further Considerations

apparent very significant debt-service payments on

securities; the position data on resident securities in-

volved in cross-border reverse transactions could in-

dicate that reverse transactions are a factor.

Information on the Creditor

16.37 In any debt analysis an understanding of the

creditor is relevant because different creditors have

different motivations and influences upon them.

16.38 The sector and country of lender are impor-

tant factors in debt analysis. Debt analysis has tradi-

tionally focused on sectors—in particular, on the split

between the official sector, banking, and other,

mostly private, sectors. The importance of this sec-

toral breakdown lies in the different degrees of diffi-

culty for reaching an orderly workout in the event of

payment difficulties. For instance, negotiations of

debt relief will differ, depending on the status of the

creditor. The official sector and the banks constitute a

relatively small and self-contained group of creditors

that can meet and negotiate with the debtor through

such forums as the Paris Club (official sector), and

London Club (banks). By contrast, other private cred-

itors are typically more numerous and diverse.

16.39 Also, the public sector may be a guarantor

of debts owed to the foreign private sector. Often this

is the case with export credit, under which the credit

agency pays the foreign private sector participant in

the event of nonpayment by the debtor, and so takes

on the role of creditor. These arrangements are in-

tended to stimulate trade activity, and premiums are

paid by the private sector. In case of default, the ulti-

mate creditor is the public sector, if the credit agency

is indeed in the public sector. The country of credi-

tor is important for debt analysis because overcon-

centration of the geographic spread of creditors has

the potential for contagion of adverse financial activ-

ity. For instance, if one or two countries are main

creditors, then a problem in their own economies or

with their own external debt position could cause

them to withdraw finance from the debtor country.

Indeed, concentration by country and sector, such as

banks, could make an economy highly dependent on

conditions in that sector and economy.

183