1

Paid Leave and Employment Stability of First-Time

Mothers

Issue Brief—Worker Leave Analysis and Simulation Series

1

January 2017

In this Issue Brief, we use data from the

2008 Survey of Income and Program

Participation’s (SIPP) Fertility History

Module to examine the association

between paid leave use and the

employment stability of first-time

mothers.

We find that first-time mothers who

utilized paid leave are significantly less

likely to quit their jobs before or after

the birth, and are significantly more

likely to work for the same employer

upon returning to work.

For more findings in the Worker Leave

Analysis and Simulation Issue Brief

Series, please visit

https://www.dol.gov/asp/evaluation/W

Welcoming a new child commonly requires working parents to face challenging

decisions related to balancing their career obligations with the extensive caregiving

responsibilities of a new child. Within this Issue Brief, we explore the association

between paid leave use and the employment stability of a specific group of parents,

first-time mothers, using data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2008 Survey of Income

and Program Participation’s (SIPP) Fertility History Module. Our analysis finds that

expecting mothers who utilize paid leave during and after their pregnancy have a

greater ability to balance their career and caregiving responsibilities, and are

subsequently more likely to experience employment stability. In contrast, mothers

who do not utilize paid leave face a greater likelihood of separating from their jobs in

order to care for a newborn child.

Our analysis, employing a propensity-score matching technique, finds that mothers

who utilized paid leave were significantly less likely to quit their jobs before or after

the birth, and were significantly more likely to work for the same employer upon

returning to work. Controlling for observed differences, first-time mothers who

utilized paid leave had only a 2.6% probability of quitting their jobs and a 92.3%

probability of returning to the same employer post-birth of their children. In

contrast, first-time mothers who did not utilize paid leave experienced a 34.3%

probability of quitting their job and had a 73.3% probability of working for the

same employer after birth.

orkerLeaveStudy/

PAID LEAVE USE AMONG FIRST-TIME MOTHERS

An analysis of the SIPP data demonstrates notable differences in the types of paid leave utilized by working mothers who gave birth

to their first child between 2000 and 2008. A small majority of first-time mothers (52%) utilized paid leave before and after the birth

of their first child. First-time mothers most commonly utilized paid maternity leave (38% of all first-time mothers), followed by paid

vacation (8.4%), paid sick leave (7.9%), paid disability leave (7.0%), or another type of paid leave (1.1%).

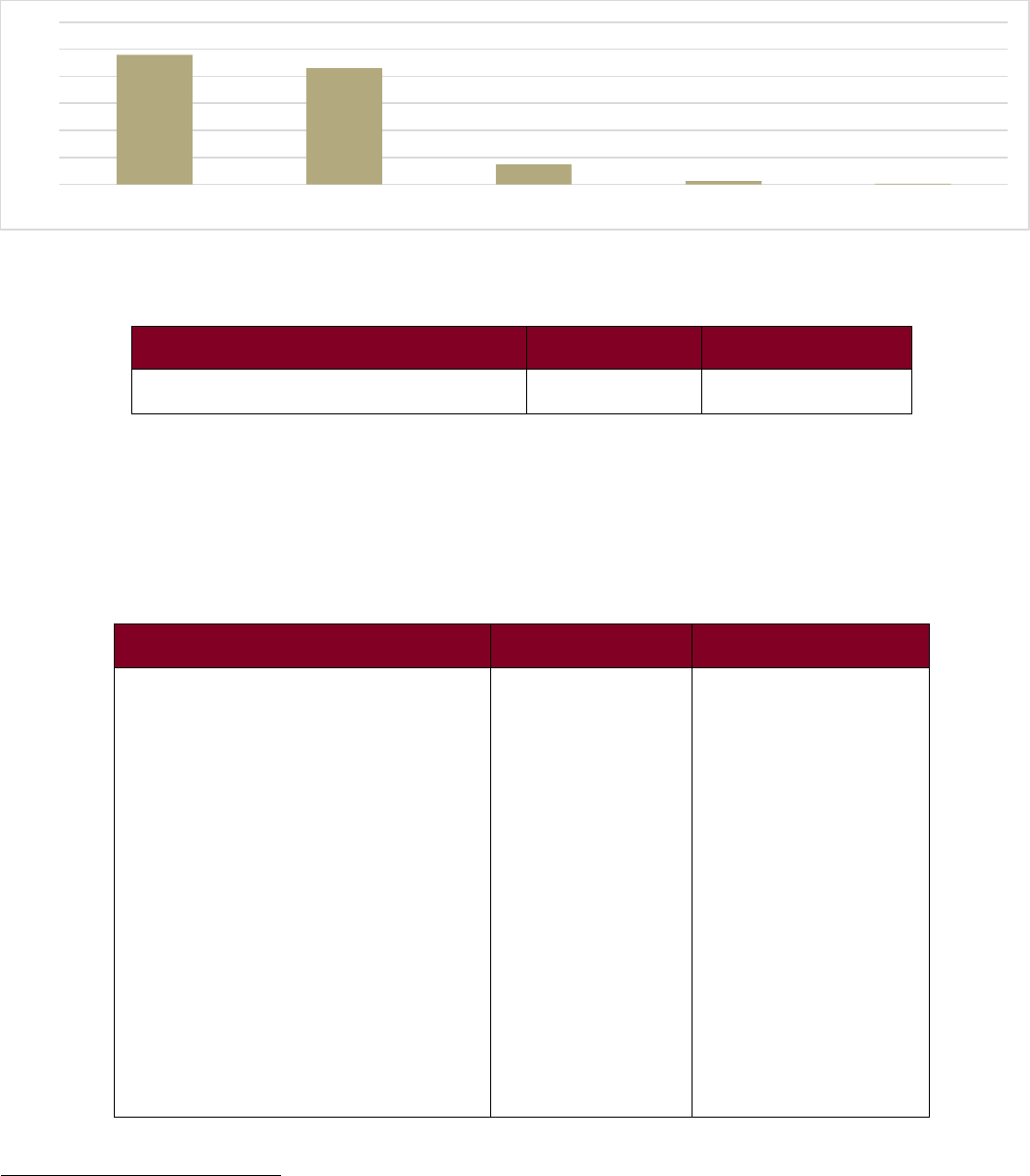

Among fir

st-time mothers who utilized paid leave, the majority took a single type of paid leave while a small percentage utilized

multiple types of paid leave during their pregnancy (see Figure 1 on the following page).

1

This project was funded, either wholly or in part, with Federal funds from the U.S. Department of Labor’s Chief Evaluation Office under Contract # DOL-OPS-14-

U-00040. The contents of this publication do not represent the views or policies of the Department.

2

Figure 1. Number of Types of Paid Leave Used by First-Time Mothers (by %)

In addition, first-time mothers who utilized paid leave

2

were significantly more likely to experience employment stability

3

than

mothers who did not utilize paid leave, as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1. Paid Leave Use and Employment Outcomes of First-Time Mothers

Statistical significance at the following levels: *p<0.10; **p<0.05; ***p<0.01

However, these differences can be attributed, in part, to systematic differences in a wide variety of characteristics of first-time

mothers who utilized paid leave and who didn’t. As shown in Table 2, mothers who utilized paid leave during their first

pregnancy are more likely to be older, less likely to be a racial or ethnic minority, and more likely to be married at birth,

have a higher education, and work full-time before the birth. By controlling for these differences, our analysis provides a

more accurate description of the association between paid leave utilization and employment stability of first-time mothers.

Table 2. Differences between First-Time Mothers Who Used Paid Leave and Who Did Not

Utilized Paid Leave During

Pregnancy

Did Not Utilize Paid Leave

During Pregnancy

Mother Quit Job Before or After Birth***

Mother Worked for Same Employer After

Birth***

Age at Birth***

3.7%

90.5%

28.9

31.1%

65.4%

25.9

Ethnicity

Hispanic Ethnicity

Non-Hispanic Ethnicity

9.5%

90.5%

10.5%

89.5%

Race***

Racial Minority

17.0%

21.3%

Caucasian/White

83.0%

78.7%

Marital Status***

Married at Birth

Unmarried at Birth

76.1%

23.9%

42.3%

57.7%

Highest Education***

High School or Less

Some College

Vocational/Associates Degree

College Graduate

Graduate Degree

15.0%

14.1%

19.0%

33.4%

18.5%

28.4%

17.0%

23.3%

20.1%

11.2%

Worked Full-Time before the Birth***

95.7%

79.7%

Number of Observations

1,415

1,303

Statistical significance at the following levels: *p<0.10; **p<0.05; ***p<0.01

2

Paid leave within this issue brief is defined as utilizing one or more or the following types of leave before or after the birth: Paid Maternity Leave, Paid Vacation,

Paid Sick Leave, Disability Leave, and Other Paid Leave.

3

The employment stability outcomes of ‘quit job’ and ‘returned to work at the same employer’ were asked via separate questions within the SIPP survey’s Fertility

History Module. Accordingly, the percentages reported in table 2 for quitting and returning to work are independent of one another. Mothers who did not return to

work at the same employer may not have returned due to reasons other than quitting, such as being let go from their job, an employer going out of business, or some

other circumstance.

47.9%

43.0%

7.5%

1.3%

0.3%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

0 1 2 3 4

Utilized Paid Leave

During Pregnancy

Did Not Utilize Paid Leave

During Pregnancy

Quit Job Before or After the Birth***

3.7%

31.1%

Returned to Work at Same Employer After Birth***

90.5%

65.4%

3

METHODOLOGY

To examine the effects of paid leave use on the employment stability for first-time mothers, we adopted propensity score matching to

control for the observable differences between first-time mothers who utilized or did not utilize paid leave. To implement the

propensity score matching process, we estimated the conditional probabilities of whether a first-time mother utilized paid leave with

the collection of 40 variables identified in Appendix A to match members of the treatment group (first-time mothers who utilized

paid leave) to members of the comparison group (first-time mothers who did not utilize paid leave). A detailed discussion of the

methodological approach can be found in Appendix B.

FINDINGS

Mothers who utilized paid leave were significantly less likely to quit their job before or after the birth (p<0.01). The findings for the

matched comparison group demonstrates a consistent, significant effect between the use of paid leave and a decreased likelihood of

quitting among first-time mothers. Among first-time mothers who did and did not utilize paid leave, the predicted probabilities

4

of

quitting a job before or after birth are as follows:

Mothers who did not utilize paid leave had a 34.3% probability of quitting their job before or after the birth (p<0.01).

In contrast, mothers who utilized paid leave had a 2.6% probability of quitting their job before or after the birth (p<0.01).

The marginal effect of quitting among mothers utilizing paid leave was -26.3% (p<0.01), with a 95% confidence interval of

-25.3% to -27.3%.

First-time mothers who utilized paid leave were also more likely to work for the same employer after birth (p<0.01). Once again, the

findings for the matched comparison group demonstrates a consistent, significant effect between the use of paid leave and an

increased likelihood of working for the same employer post-birth among first-time mothers. Among first-time mothers who did and

did not utilize paid leave, the predicted probabilities of returning to work at the same employer after birth are as follows:

Mothers who did not utilize paid leave had a 73.3% probability of working for the same employer after the birth (p<0.01).

In contrast, mothers who utilized paid leave had a 92.3% probability of working for the same employer after the birth

(p<0.01).

The marginal effect of working for the same employer after birth among mothers utilizing paid leave increased by 18.2%

(p<0.01), with a 95% confidence interval of 14.2% to 22.1%.

IMPLICATIONS

In this brief, we find a significant relationship between the use of paid leave and greater employment stability among first-time

mothers. First-time mothers who utilized paid leave were 26.3 percentage points less likely to quit their jobs than mothers who

did not utilize paid leave (p<0.01). In addition, mothers who utilized paid leave were 18.2 percentage points more likely to

work for the same employer after the birth of their first child (p<0.01). These findings suggest that mothers that utilize paid

leave benefits provided by their employer may experience a greater ability to balance their career and caregiving

responsibilities. In addition, these findings suggest that employers that offer paid leave benefits may be more likely to

experience increased levels of employee retention, as first-time mothers who utilize paid leave are more likely to return to

their job.

T

hese findings are subject to two notable limitations. First, this analysis limits its focus to first-time mothers. Additional research is

needed to examine whether the use of paid leave benefits produces greater employment stability among other key populations of U.S.

workforce. Second, while propensity score matching controls for the observable differences between first-time mothers who utilized

or did not utilize paid leave, the methodology does not control for unobserved differences. Due to this inability to control for

unobservable differences, the possibility exists that mothers who utilized paid leave could have differed from mothers who did not, in

important ways. Despite these limitations, this analysis takes a rigorous approach to identifying a statistically significant relationship

between the use of paid leave and employment stability among first-time mothers in a nationally representative sample. Given the

promising findings, future research is recommended to determine if paid leave produces greater employment stability for first-time

mothers.

4

The predicted probabilities and marginal effects for the paid leave treatment variable were calculated by setting all other explanatory variables to their mean values.

4

APPENDIX A: MATCHING VARIABLES

1. Hispanic Ethnicity

2. How Mother became a Naturalized Citizen

3. Immigration Status upon Entry to the U.S.

4. Married at Birth

5. Mother became Separated from Her Partner before the Birth

6. Mother became Unable to Work before the Birth, Due to a Health Limitation

7. Mother Did not Have Health Insurance before the Birth

8. Mother had Multiple Separations from Partners before the Birth

9. Mother had a Birth in California after the Passage of the California Paid Family Leave Program

10. Mother had a Gap in Health Insurance before the Birth

11. Mother had a Second Marriage before the Birth

12. Mother had a Work Limitation Before the Birth

13. Mother had Other Circumstances that Led to a Stop in Work after Birth

14. Mother had Other Circumstances that Led to a Stop in Work before Birth

15. Mother Moved in the Year Before, During, or After the Pregnancy

16. Mother Moved to the U.S.

17. Mother Never Stopped Working after Birth

18. Mother Never Stopped Working before Birth

19. Mother Was a Permanent U.S. Resident before the Birth

20. Mother Was Let Go from Job after Birth

21. Mother Was on Medicaid before the Birth

22. Mother Was on Other Unpaid Leave before Birth

23. Mother Was on Unpaid Maternity Leave before Birth

24. Mother Was on Unpaid Sick Leave before Birth

25. Mother Was on Unpaid Vacation Leave before Birth

26. Mother Was Self-Employed after Birth

27. Mother Was Self-Employed before Birth

28. Mother Worked Full-Time Before Birth

29. Mother’s Age at Birth

30. Mother's Employer went Out-of-Business after Birth

31. Mother's Employer went Out-of-Business before Birth

32. Mother’s First Marriage was Terminated before the Birth

33. Mother had Multiple Marriages Terminated before the Birth

34. Mother’s Highest Level of Education

5

35. Mother’s Year of Birth

36. Racial Minority

37. SIPP Person Weight

38. US Citizenship Status

39. Year First Child was Born

40. Year that the Mother Stopped Working Before the Birth

5

Mother’s highest level of education was measured at the time the survey was conducted.

5

APPENDIX B: METHODOLOGY

Data for the analysis consisted of survey data from the 2008 Survey of Income and Program Participation’s (SIPP) Fertility History

Module. The Fertility History Module, administered in January through April of 2009, asked mothers a variety of questions

pertaining to the birth of their first child. This analysis restricted its focus to working mothers who gave birth to their first child

between 2000 and 2008 (n=2,718). This unmatched sample consisted of an unmatched treatment group of 1,415 mothers who utilized

paid leave during their first pregnancy and an unmatched comparison group of 1,303 mothers who did not utilize paid.

In order to control for the observable differences between first-time mothers who utilized or did not utilize paid leave, propensity

score matching and a collection of 40 variables

6

were used to construct propensity scores that were used to estimate the probability

that a first-time mother would utilize paid leave. The estimated propensity scores were utilized to match members of the treatment

group (first-time mothers who utilized paid leave) to members of the comparison group (first-time mothers who did not utilize paid

leave), with the goal of developing matched groups that are statistically identical on the matching variables. Propensity score

matching assumes that there is considerable overlap in the propensity score distribution of the treatment and comparison groups.

Following common practice, individuals on the extreme ends of the propensity score who were outside of the common support were

removed from the matching process, which consisted of 59 individuals in the comparison group and 34 individuals in the treatment

group.

A variety of matching methods were evaluated

7

, with Full-Matching selected as the optimal method. Full matching offers a more

flexible approach than greedy matching methods, such as exact or nearest neighbor matching, by making use of all individuals in the

common support region of propensity scores. The method constructs a series of matched sets comprised of either one treated

individual and multiple comparison individuals or one comparison individual and multiple treated individuals

8

. The final model

matched 1,381 mothers using paid leave to 1,244 mothers who did not utilize paid leave.

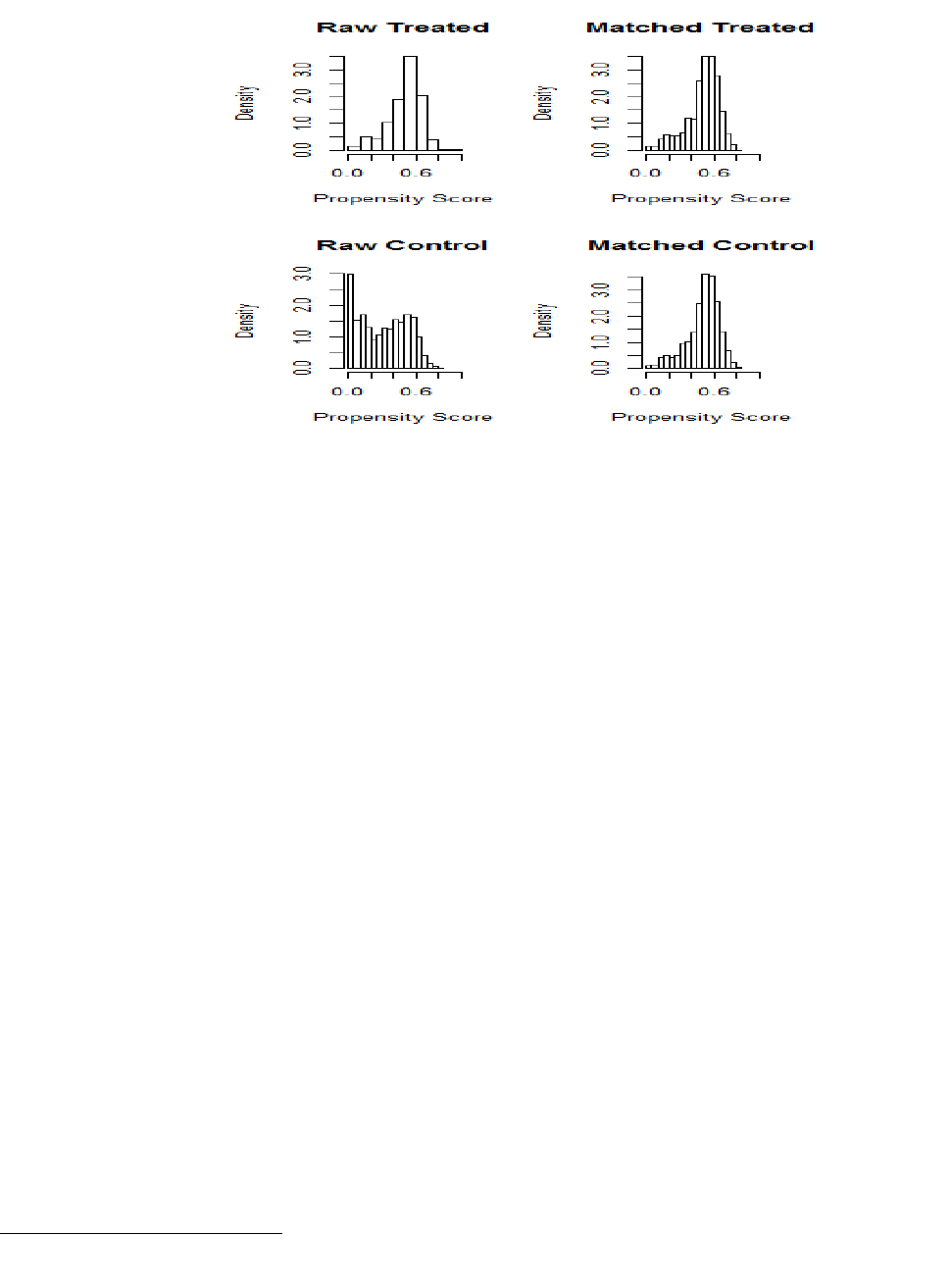

A combination of numerical and graphical diagnostics demonstrated a high-level of covariate balance between the two groups. Figure

2 on the following page shows the distribution of the propensity score before and after matching.

6

Stuart, E. A. (2010). Matching methods for causal inference: A review and a look forward. Statistical Science: A Review Journal of the Institute of Mathematical

Statistics, 25(1), 1-21.

7

Including coarsened exact matching, exact matching, full matching, genetic matching, nearest neighbor matching, Optimal matching, and Sub-classification.

8

Probability weights were calculated for all members of the matched sample and the post-matching analysis was conducted using weighted logistic regression models.

6

Figure 2. Distribution of Propensity Scores Before and After Matching

(By Treatment and Comparison Groups)

Prior to matching, the mean propensity scores were 0.6615 for the treatment group and 0.3675 for the comparison group, with a

standardized mean difference of 1.6145. Standardized mean differences above 0.25 are considered evidence of considerable bias.

9

After matching, the propensity score for both the treatment and comparison groups were 0.6550 and 0.6549, respectively, with a

mean standardized difference of 0.0003. All 40 matching covariates were below the common standard of 0.25 absolute standardized

difference of means. Overall, the matching process produced considerable improvement in the balance of the propensity scores for

the treatment and matched groups. Table 3 provides an overview of the differences in the unmatched and matched samples.

9

Rubin, D. B. (2001). Using propensity scores to help design observational studies: application to the tobacco litigation. Health Services and Outcomes

Research Methodology, 2(3-4), 169-188.

7

Table 3. Differences in Paid Leave Use within the Unmatched and Matched Samples

(For Variables Included in the Multivariate Models)

Unmatched Sample

Matched Sample

Utilized Paid

Leave

Did Not Utilize Paid

Leave

Utilized Paid

Leave

Did Not Utilize Paid

Leave

Age at Birth***

28.9

25.9

28.8

28.9

Ethnicity

Hispanic Ethnicity

Non-Hispanic Ethnicity

9.5%

90.5%

10.5%

89.5%

9.1%

91.0%

9.8%

90.3%

Race***

Racial Minority

17.0%

21.3%

16.9%

18.8%

Caucasian/White

83.0%

78.7%

83.1%

81.2%

Marital Status***

Married at Birth

Unmarried at Birth

76.1%

23.9%

42.3%

57.7%

75.8%

24.2%

75.2%

24.8%

Highest Education***

High School or Less

Some College

Vocational/Associates Degree

College Graduate

Graduate Degree

15.0%

14.1%

19.0%

33.4%

18.5%

28.4%

17.0%

23.3%

20.1%

11.2%

15.1%

14.2%

19.3%

32.8%

18.6%

13.9%

15.8%

19.3%

35.2%

15.9%

Worked Full-Time before the Birth***

95.7%

79.7%

95.6%

95.1%

Number of Observations

1,415

1,303

1,381

1,244

Statistically significant differences in the unmatched sample at the following levels: *p<0.10; **p<0.05; ***p<0.01

A series of weighted

10

and logistic regression models with probability weights were utilized to examine the association between paid

leave use and employment stability in the matched sample and to examine the robustness of the findings across models. These

models consisted of:

Model 1: Bivariate logistic regression model with robust standard errors

Model 2: Multivariate logistic regression model with covariates and robust standard errors

Model 3: Multivariate logistic regression model with covariates, year fixed effects

11

, and robust errors clustered on the year that

the birth occurred

Model 4: Multivariate logistic regression model with covariates, year fixed effects, state fixed effects, and robust, state clustered

errors

12

Tables 4 and 5 provide the model results for the ‘Quit Job’ and ‘Returned to Work at Same Employer’ outcome variables. Model

coefficients consist of log-odds, with the associated standard errors included in parentheses. For ease of interpretation, the findings

provided on page 3 consisted of the marginal effects for the treatment variables included in Model 4. The marginal effects for the

paid leave treatment variable were calculated by setting all of the covariates to their mean values.

10

The weights utilized in the logistic regression models consisted of the probability weights for all individuals in the matched sample that were calculated via the

matching process.

11

Year fixed effects and clustered errors were included to account for differences in the year that the birth occurred.

12

State fixed effects and clustered errors were included to account for differences across state economies and workforces.

8

Table 4. Logit Models with Log-Odds Coefficients

(See Endnotes for Coefficient Interpretation

13,14

)

Outcome: Mother Quit Job Before

or After the Birth

Model 1:

Bivariate

Model 2:

Covariates

Model 3: Covariates

with Year Fixed Effects

Model 4: Covariates, Year Fixed

Effects, and State Fixed Effects

Treatment: Paid Leave

-2.745***

(0.187)

-2.778***

(0.187)

-2.822***

(0.217)

-2.986***

(0.2398)

Worked Full-Time Before

-0.191

(0.225)

-0.298

(0.255)

-0.396

(0.274)

Minority

-0.214

(0.311)

-0.182

(0.231)

-0.390*

(0.228)

Hispanic Origin

-0.207

(0.361)

-0.202

(0.320)

-0.308

(0.384)

Age at Birth

-0.019

(0.020)

-0.020

(0.017)

-0.008

(0.027)

Married at Birth

0.412*

(0.241)

0.382**

(0.225)

0.358

(0.269)

Highest Education

(Reference: College Graduate)

HS or Less

0.145

(0.308)

0.204

(0.314)

0.481

(0.302)

Some College

-0.296

(0.338)

-0.117

(0.378)

-0.106

(0.320)

Vocational/Associates Degree

-0.268

(0.298)

-0.284

(0.231)

0.064

(0.249)

Graduate Degree

-0.671*

(0.350)

-0.556

(0.394)

-0.468

(0.313)

Year Fixed Effects

Yes

Yes

State Fixed Effects

Yes

Constant

-0.496***

(0.122)

0.153

(0.625)

1.214**

(0.592)

-1.240*

(0.733)

Number of Observations

2,625

2,625

2,625

2,603

Statistically Significant at the Following Levels: *p<0.10; **p<0.05; ***p<0.01. Standard errors in parentheses.

13

Coefficients in Tables 4 and 5 consists of Log-Odds. For ease of interpretation, predicted probabilities and marginal effects were calculated for the treatment

variables.

14

Twenty-two observations were dropped in the year and state fixed effects model (model 4), due to a lack of variation in outcomes among mothers within each of the

following states: Mississippi, North Dakota, Vermont and the District of Columbia.

9

Table 5. Logit Models with Log-Odds Coefficients

(See Endnotes for Coefficient Interpretation)

15

Outcome: Worked for

Same Employer After Birth

Model 1:

Bivariate

Model 2:

Covariates

Model 3:

Covariates with

Year Fixed

Effects

Model 4: Covariates,

Year Fixed Effects,

and State Fixed

Effects

Treatment: Paid Leave

1.400***

(0.155)

1.425***

(0.154)

1.448***

(0.154)

1.479***

(0.208)

Worked Full-Time Before

0.304

(0.217)

0.297

(0.219)

0.278

(0.174)

Minority

0.217

(0.238)

0.199

(0.229)

0.198

(0.305)

Hispanic Origin

-0.112

(0.327)

-0.144

(0.337)

-0.144

(0.358)

Age at Birth

0.063***

(0.018)

0.065***

(0.017)

0.053***

(0.018)

Married at Birth

0.094

(0.204)

0.086

(0.203)

0.118

(0.261)

Highest Education

(Reference: College

Graduate)

HS or Less

0.276

(0.245)

0.235

(0.237)

0.087

(0.227)

Some College

0.215

(0.299)

0.066

(0.295)

0.116

(0.282)

Vocational/Associates

Degree

0.281

(0.275)

0.299

(0.260)

0.202

(0.241)

Graduate Degree

0.112

(0.290)

0.044

(0.292)

-0.035

(0.306)

Year Fixed Effects

Yes

Yes

State Fixed Effects

Yes

Constant

0.839***

(0.125)

-1.488**

(0.531)

-2.090***

(0.532)

-1.587**

(0.504)

Number of Observations

2,625

2,625

2,625

2,615

Statistically Significant at the Following Levels: *p<0.10; **p<0.05; ***p<0.01

15

Ten observations were dropped in the year and state fixed effects model (model 4), due to a lack of variation in outcomes among mothers within each of the

following states: North Dakota, Vermont, and the District of Columbia.