FAMILIES

COUNT

2024

FAMILY

STRUCTURE

FAMILIES COUNT 2024 | FAMILY STRUCTURE

THE VANIER INSTITUTE OF THE FAMILY

FAMILIES COUNT 2024 | FAMILY STRUCTURE

Family structure: the shape of families and family life . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2

1. Couples are less likely to get married . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .3

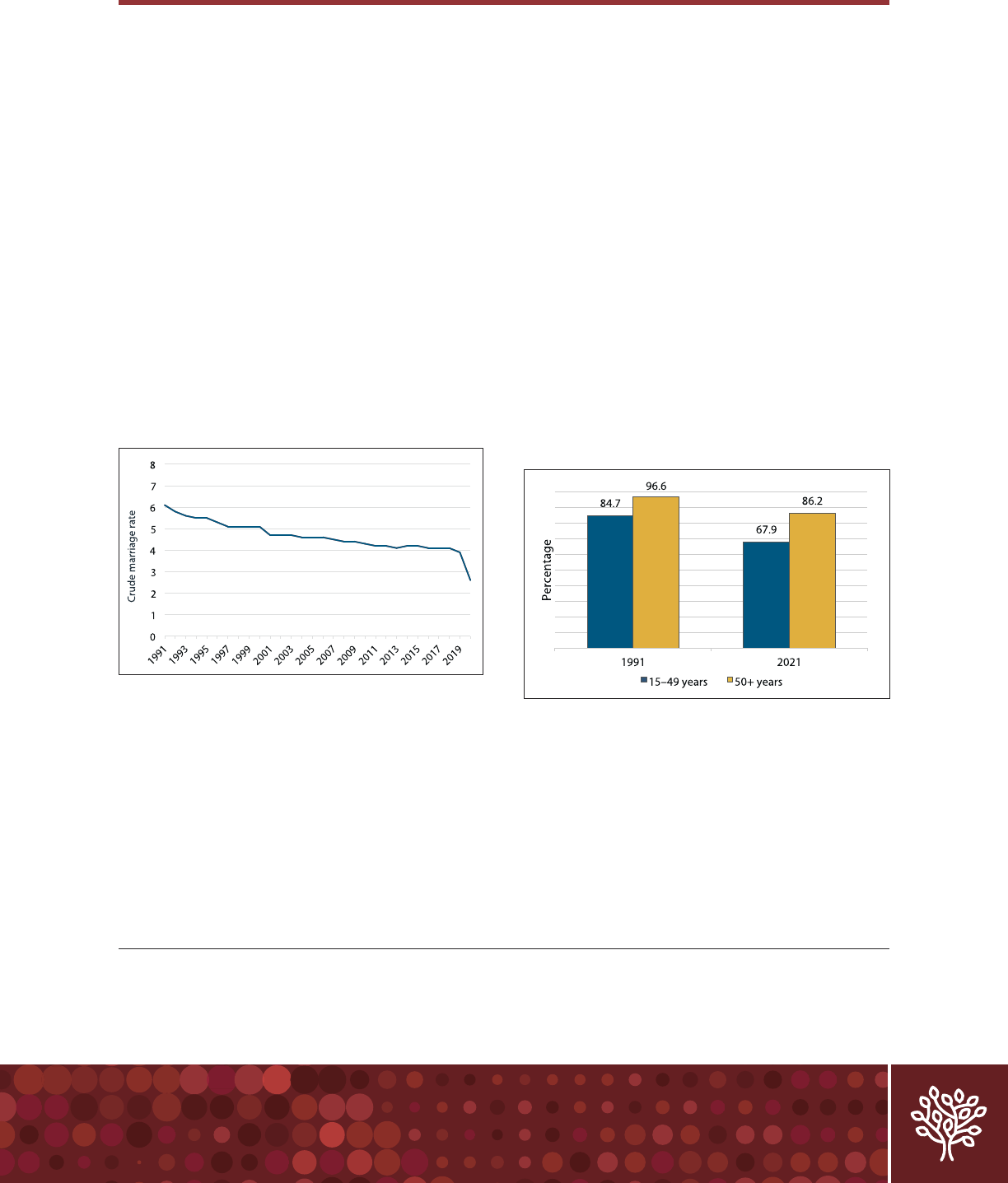

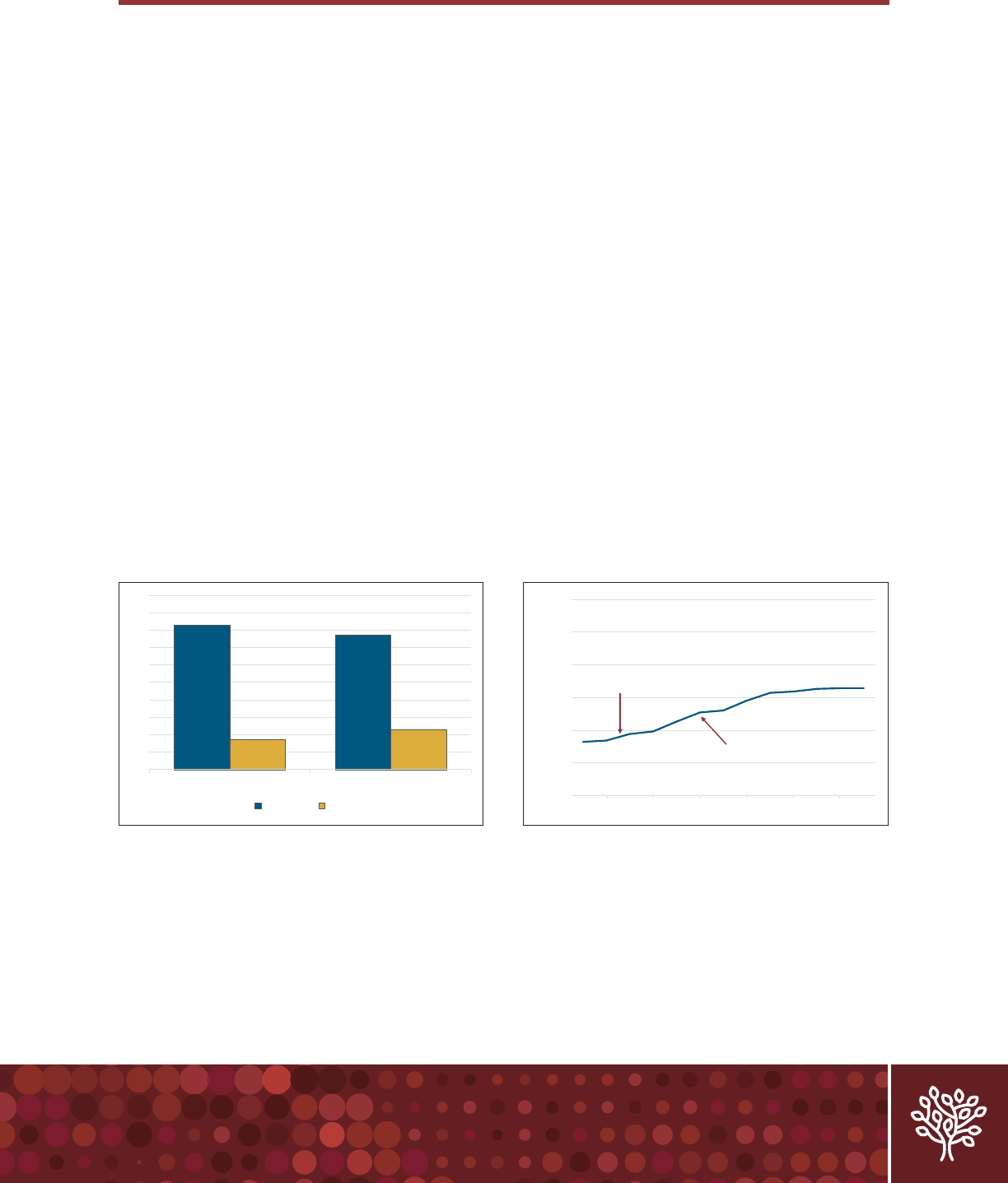

Number of marriages per 1,000 population (crude marriage rate), Canada, 1991–2020 . . . . .4

Percentage of total population aged 15 to 49 and 50 and older in couples

who were married, Canada, 1991 and 2021 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4

2. Couples are marrying later in life . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .5

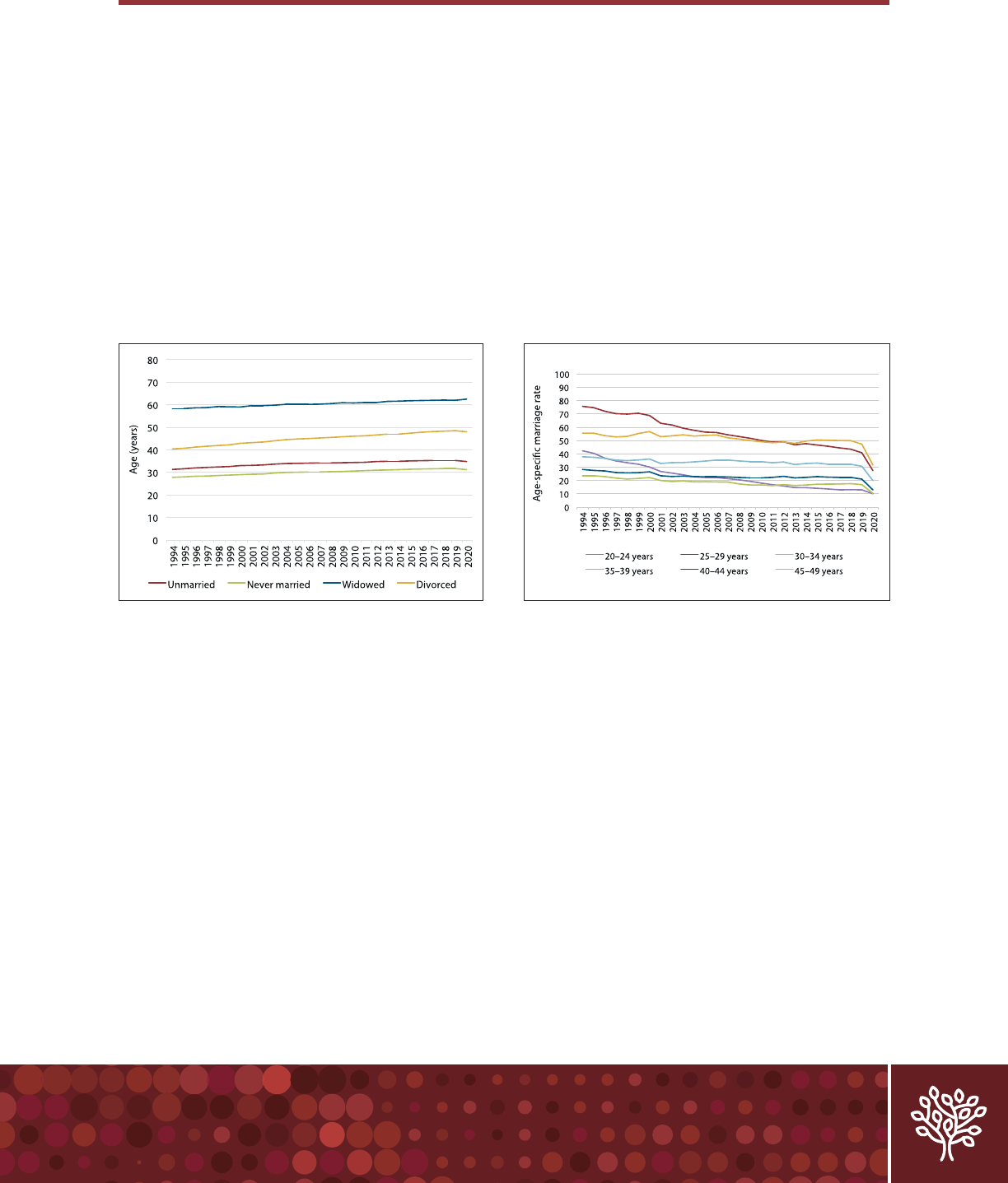

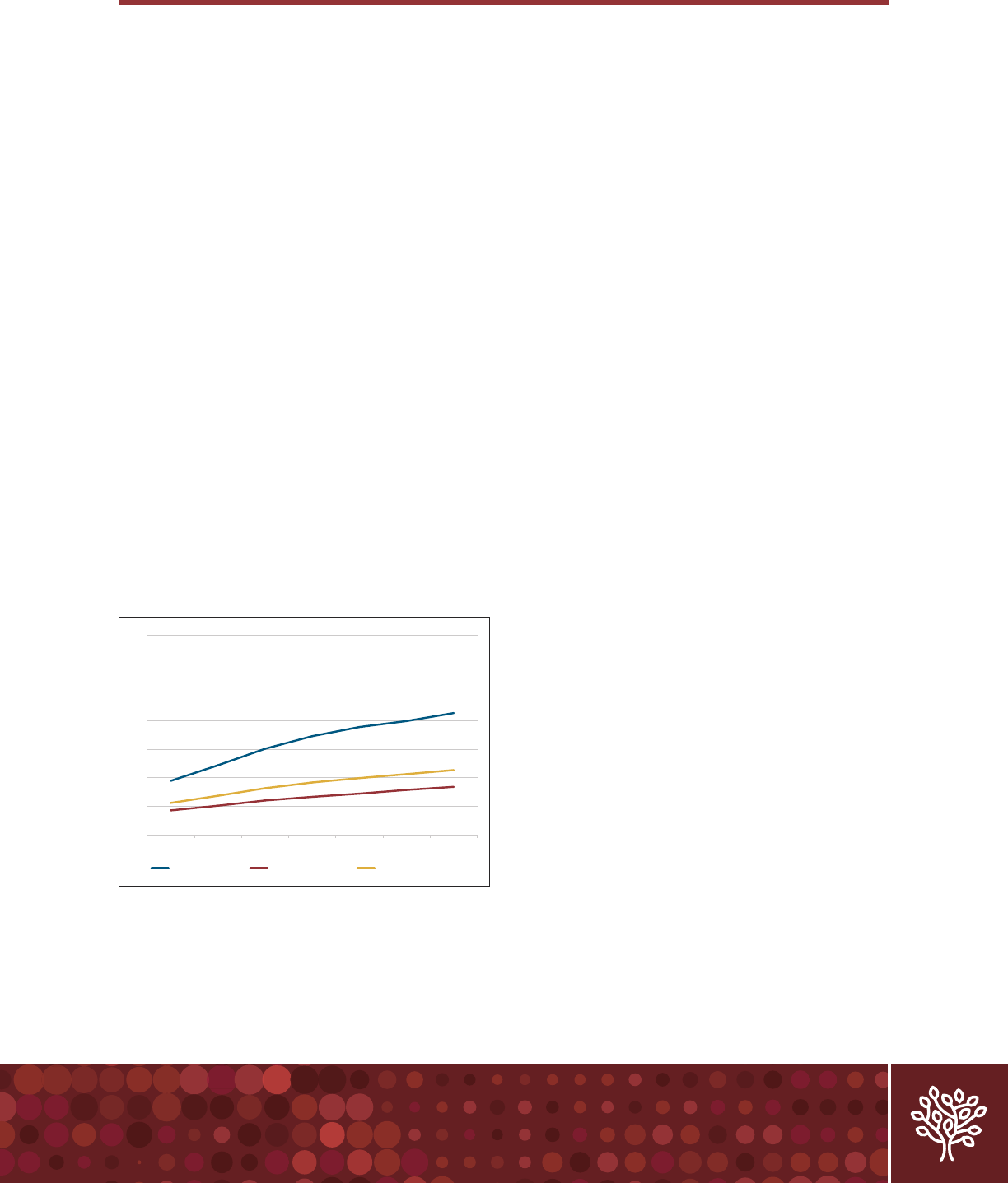

Average age at marriage, by legal marital status prior to marriage, Canada, 1994–2020 . . . .6

Marriage rate per 1,000 unmarried persons, by age group, Canada, 1994–2020 . . . . . . . . . . . .6

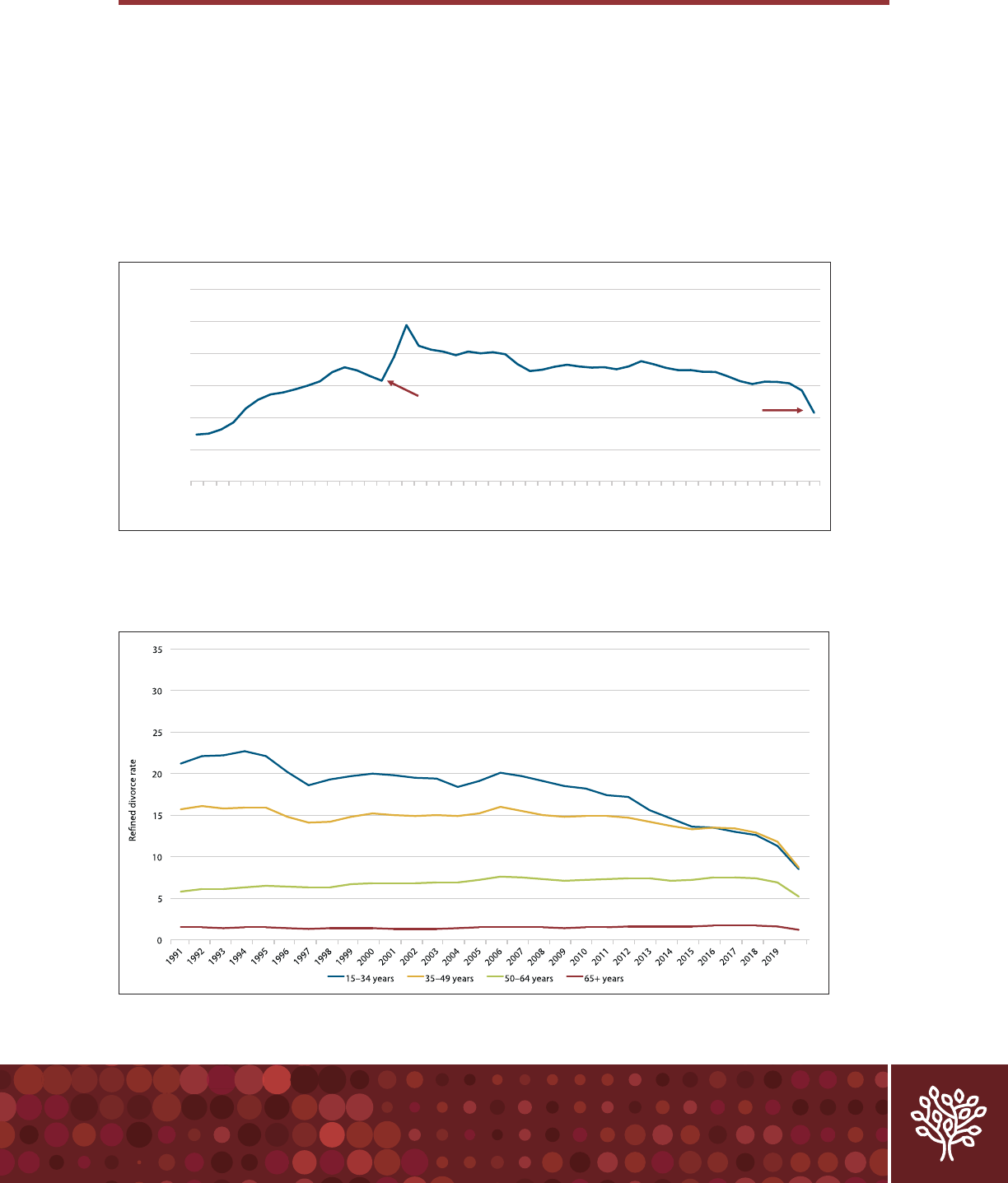

3. Divorce rates have declined since the early 1990s . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .7

Number of divorces, Canada, 1970–2020 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .8

Number of persons who divorced per 1,000 married persons (refined divorce rate)

by age group, Canada, 1991–2020 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .8

4. Common-law unions are most common in Quebec and Nunavut . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .9

Percentage of all couples that were common-law, inside Quebec and outside Quebec,

1991–2021 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .10

5. Living apart is increasingly common among couples . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .11

Proportion of the population living alone in a living apart together (LAT) relationship,

by age group and gender, Canada, 2017 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .12

6. Polyamorous families have broadened family law . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .13

7. Young adults are more likely to live with parents . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .15

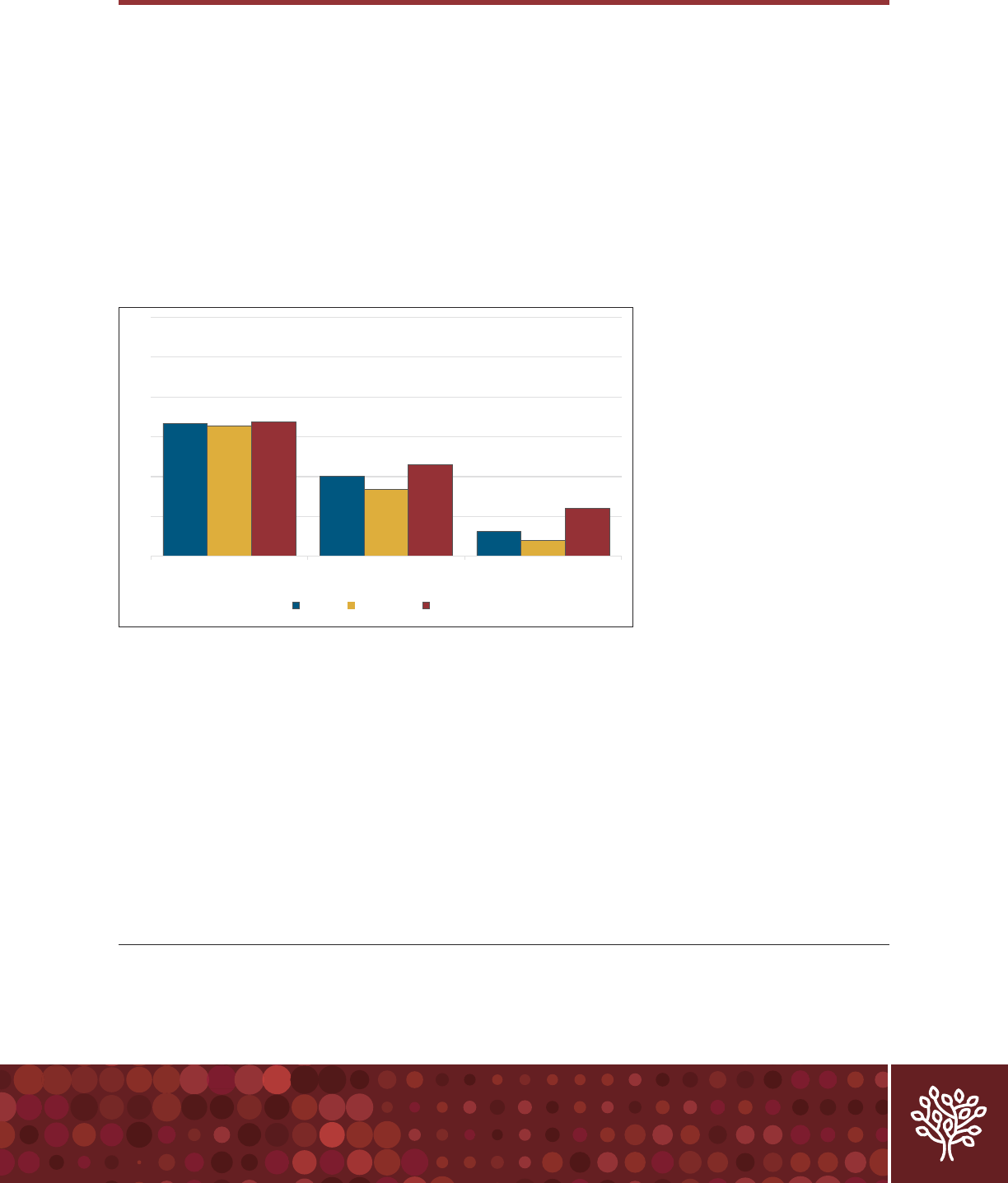

Percentage of the population aged 20 to 29 living with at least one parent,

by age group, Canada, 1991 and 2021 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .16

8. Multigenerational households are one of the fastest growing household types . . . . . . . .17

Percentage of the population living in a multigenerational household, Canada, 2021 . . . . . . .18

Contents

FAMILIES COUNT 2024 | FAMILY STRUCTURE

9. Pathways to becoming a stepfamily have evolved . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .19

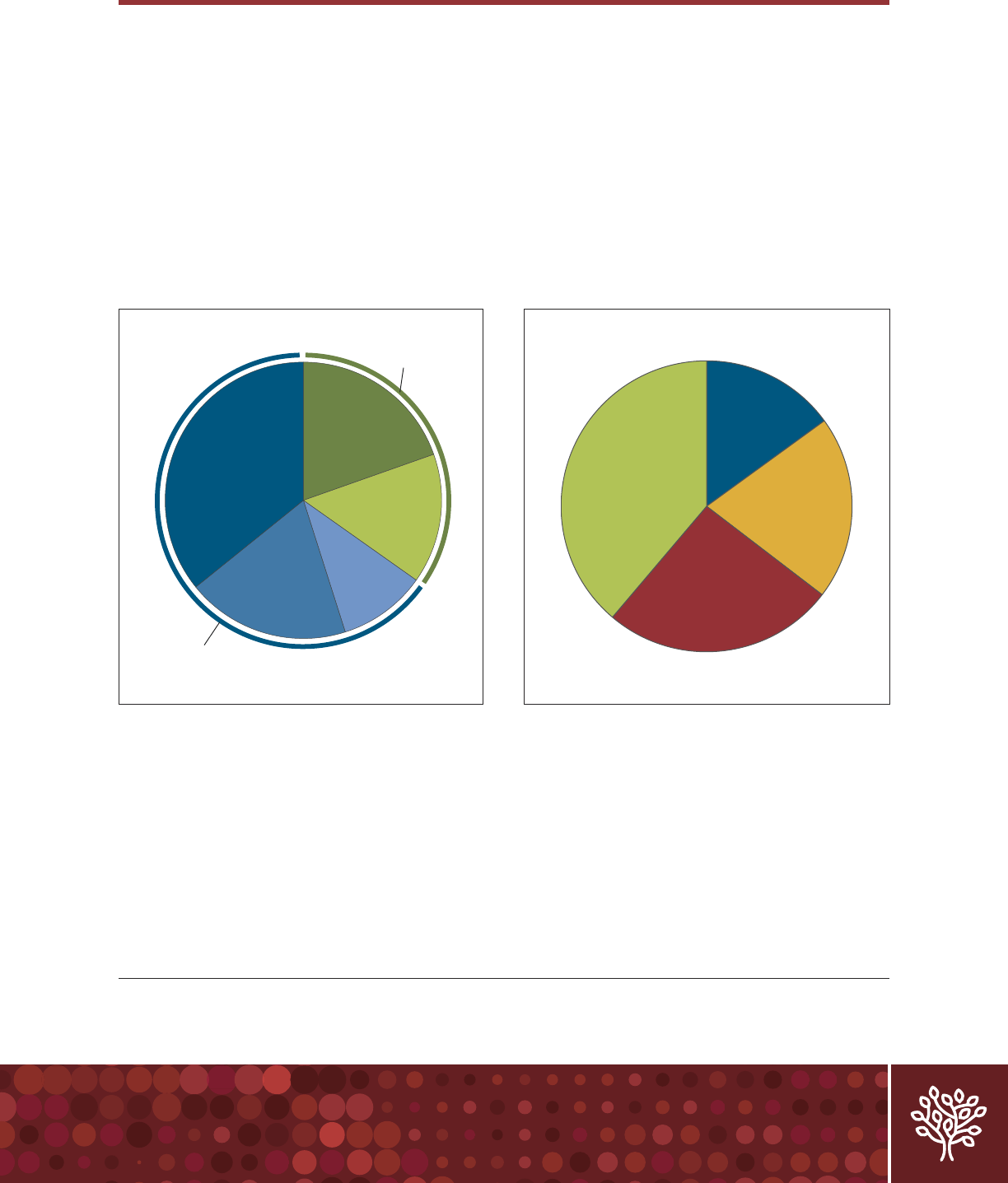

Living arrangements of children under 15 living in stepfamilies, Canada, 2021 . . . . . . . . . . . . .20

Distribution of children under 15 living in stepfamilies, by age group, Canada, 2021 . . . . . . .20

10. Fertility rates hit a record low (again) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .21

Average number of children per woman (total fertility rate), Canada, 1972–2022 . . . . . . . . .22

11. Fathers represent a growing share of parents in one-parent families . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .23

One-parent families led by mothers and fathers, Canada, 1991 and 2021 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .24

Percentage of all census families that were one-parent families, Canada, 1961–2021 . . . . . . .24

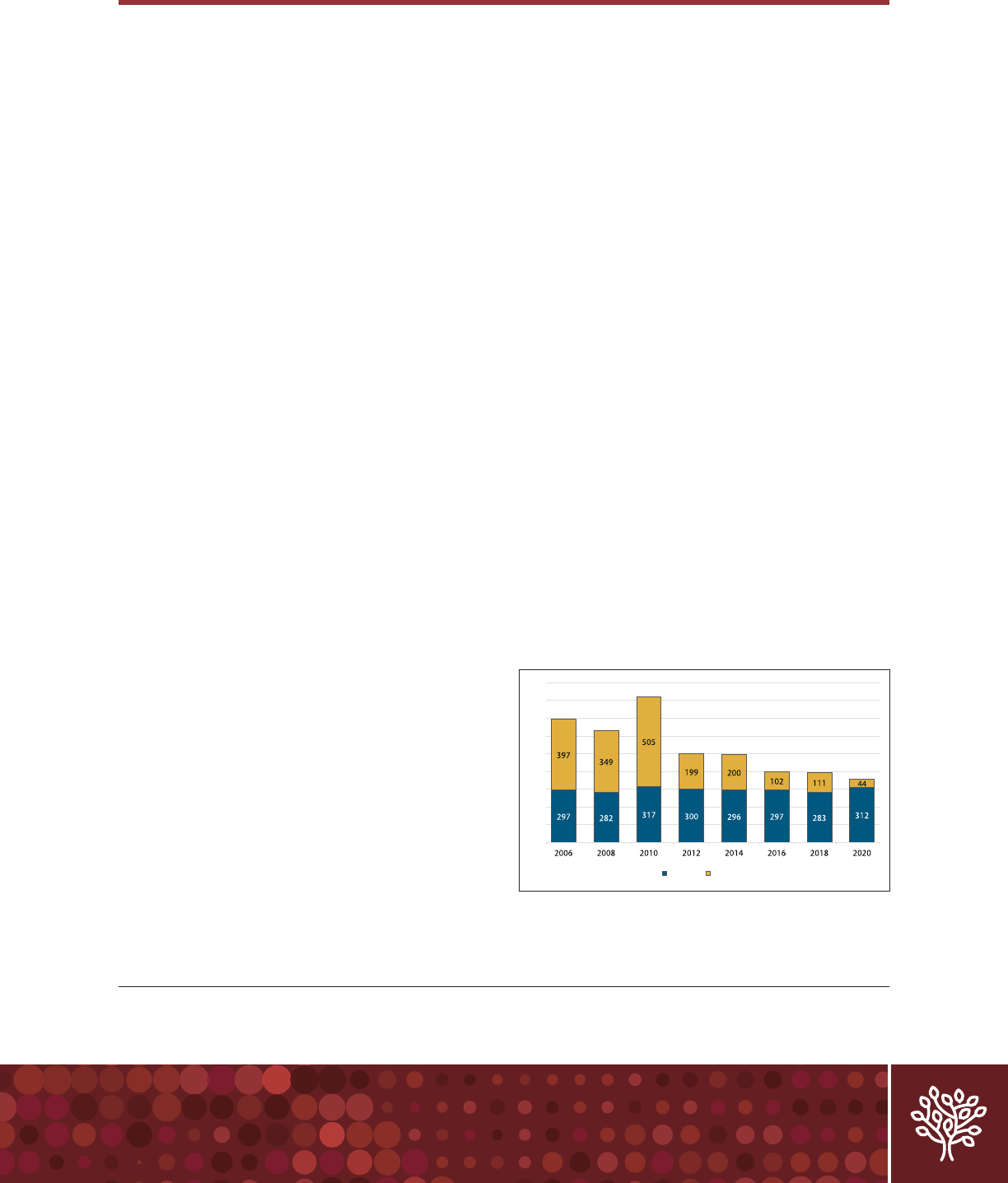

12. Thousands of children are adopted every year but far more need homes . . . . . . . . . . . . .25

Number of adoptions resulting in QPIP benefits, by adoption type, Quebec,

2006–2020 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .26

13. Half of children in foster care are Indigenous . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .27

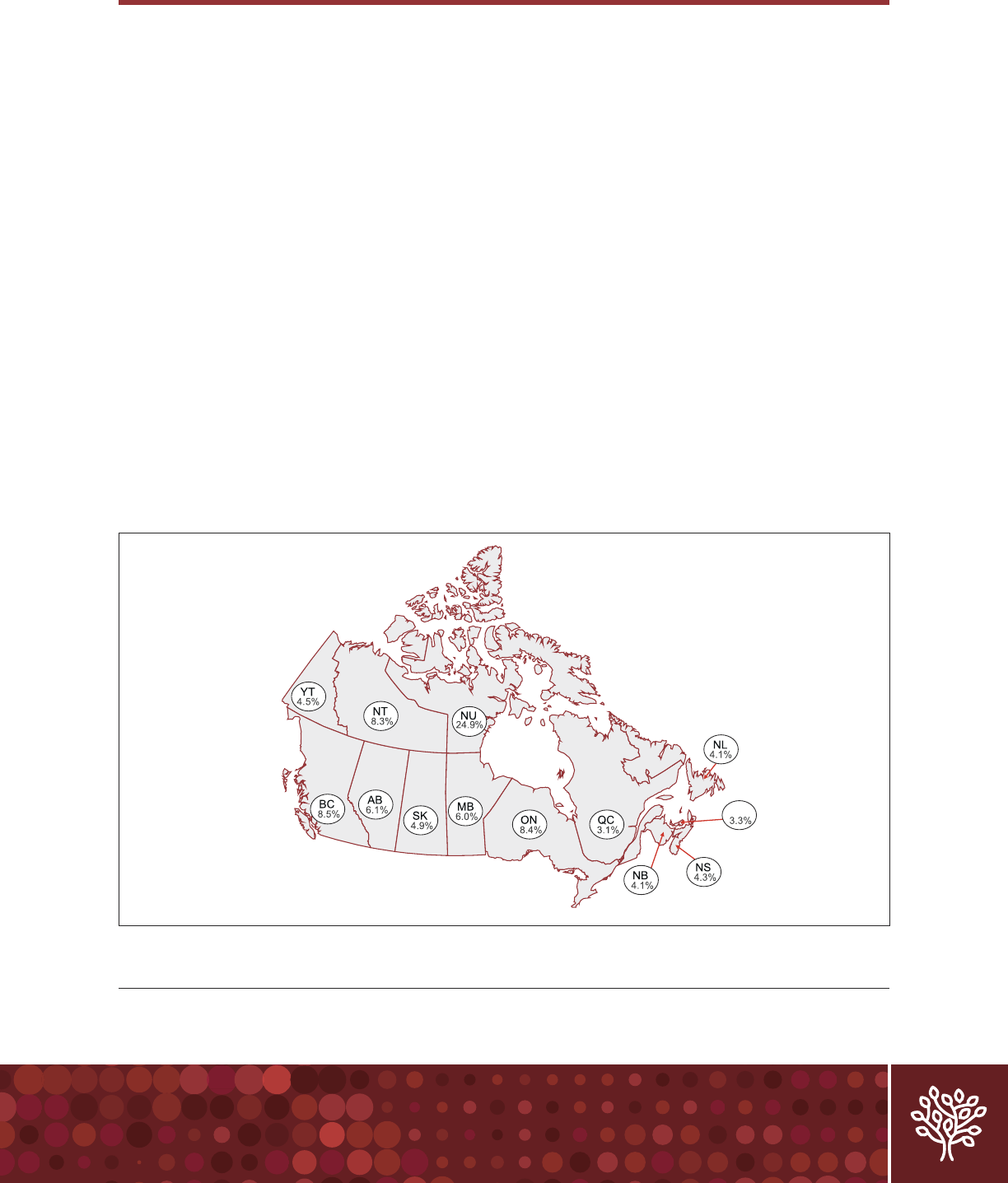

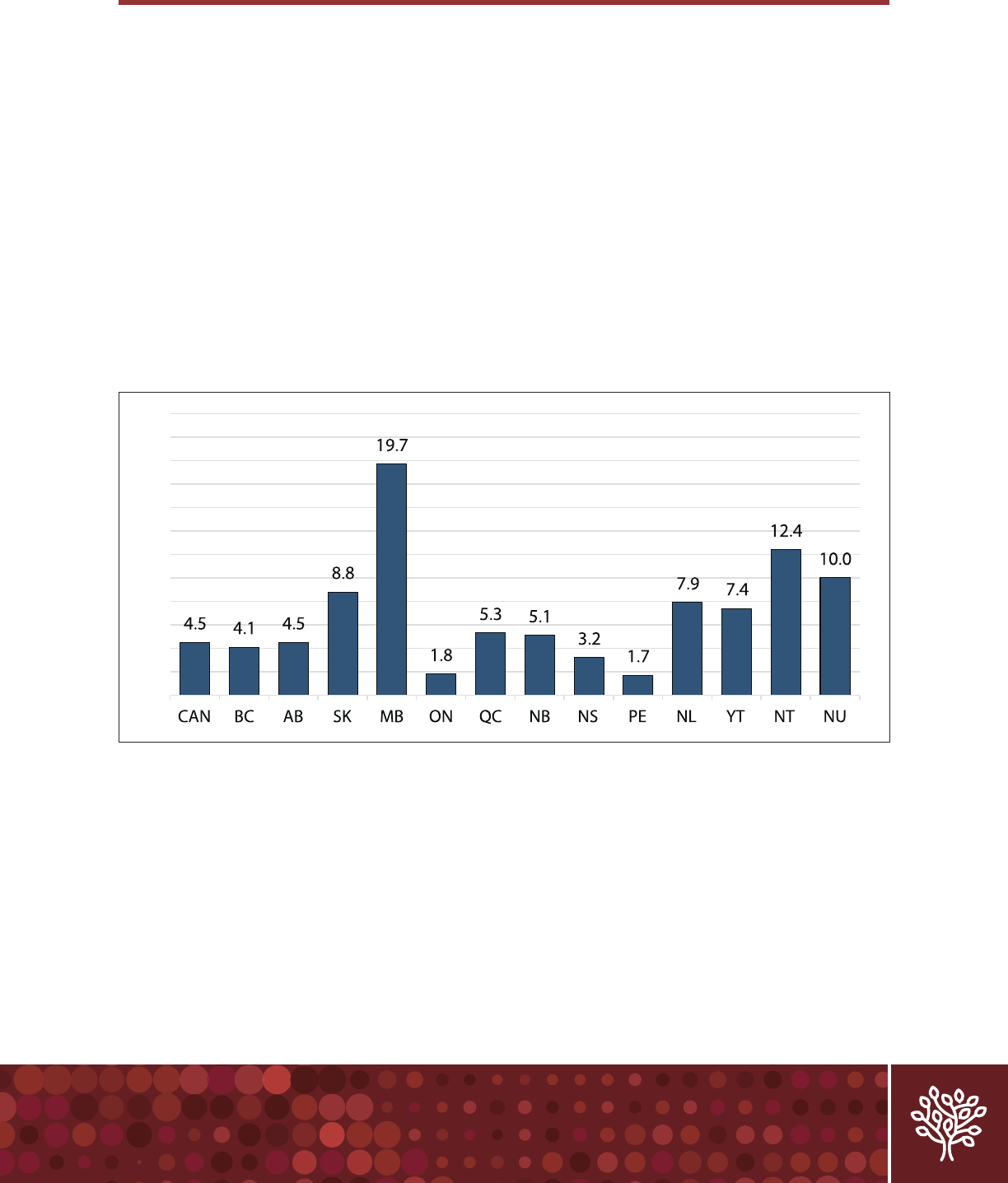

Rate of children under 15 in foster care, Canada, provinces and territories, 2021 . . . . . . . . . .28

14. The percentage of older adults who are widowed has declined . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .29

Percentage of older adults who were widowed, by gender and age group,

Canada, 2021 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .30

Percentage of the population aged 65 and older who were widowed,

by gender, Canada, 1991 and 2021 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .30

References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .31

Notes and acknowledgements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .35

About Families Count 2024 and how to cite this document . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .35

THE VANIER INSTITUTE OF THE FAMILY

FAMILIES COUNT 2024 | FAMILY STRUCTURE

Family structure: the shape of

families and family life

One of the lenses of the Family Diversities

and Wellbeing Framework focuses on

family structure. This lens represents the

combination of relationships that make up

a family or family household. It highlights

how people are linked to form and grow

families through kinship or other bonds

that are recognized in legislation or

social convention.

Focusing on family structure allows us to

shed light on how laws and policies about

family formation and dissolution reflect

societal beliefs about who makes up a

family. Importantly, it also sets boundaries

around the rights and obligations that flow

from these connections.

Family structure has several dimensions,

such as whether a family has children,

whether a family is centred around one

parent and their child(ren) or if it is a

couple family, and whether couple families

are married or living common-law. It also

explores different family household types

and living arrangements, such as in

multigenerational households, stepfamily

households, and those comprised of

grandparents and grandchildren without

the presence of a parent (i.e., skip-

generation households).

The family structure lens looks at how

families grow, whether through childbirth,

adoption, or surrogacy. It examines how

family structures and relationships change

throughout the life course, whether through

marriage, divorce, or forming a stepfamily,

or the death of family members. It

investigates less common ways that people

“do relationships,” whether as couples “living

apart together” in separate households, or in

a polyamorous relationship comprised of

more than two people.

Over the last half-century, family structures

have become considerably more diverse,

driven by social, economic, cultural, and

environmental changes. Some of these

changes have contributed to family

transitions happening later in life than

in the past, such as moving out of the

parental home, getting married, and

having children. Chapters in this section

will provide updated portraits of family

structures and will examine how changing

contexts have shaped families and family

life in Canada.

2 | THE VANIER INSTITUTE OF THE FAMILY

3 | THE VANIER INSTITUTE OF THE FAMILY

FAMILIES COUNT 2024 | FAMILY STRUCTURE

Across generations, marriage has become

less common in Canada. In 2021, more than

four in 10 people aged 15 and older were

married (44.3%),

1

down from 54.1% in

1991.

2

The decline in the number of married

people across generations can also be seen

in the relative proportion of people under

and over the age of 50 in couples who were

married. In 2021, 67.9% of the population

aged 15 to 49 living in couples were married,

compared with 86.2% of those over 50 who

were in couples.

1

The decline in marriage can also be seen

in the crude marriage rate. This is the total

number of marriages registered in a given

year, divided by the total population. This

dropped from 6.1 marriages per 1,000 people

in 1991 to 3.9 by 2019.

3

In 2020, the rate

dropped to a record low of 2.6 per 1,000.

That year, there were 98,355 marriages

registered in Canada, the lowest recorded

since 1938 when the population was much

smaller.

4

This was largely due to barriers

and restrictions resulting from COVID-19

public health measures.

Regardless of decreasing marriage rates,

couples do continue to enter conjugal

unions as much as in the past. In 2021,

56.9% of the population aged 15 and older

were part of a couple, compared with

57.9% in 1921.

5

But a growing number

of couples are now living common-law

instead of getting married. This is

particularly the case in Quebec and

Nunavut, where in 2021 only 57.3% and

48.2% of couples, respectively, were

married (vs. 77.3% across Canada).

6

Marriage is less common among same-

gender couples than different-gender

couples, partly because marriage between

two people of the same sex has only been

legal across Canada since 2005.

a

In 2021,

37.3% of same-gender couples were

married, compared with 77.8% of

different-gender couples.

5

There is no single explanation for the

decline in the proportion of couples getting

married. The increasing preference among

younger adults for common-law unions

over marriage, population aging, the

declining influence of religion in society,

and the rising average age at marriage

have all contributed to this trend.

Couples are less likely to

get married

1

FAMILIES COUNT 2024 | FAMILY STRUCTURE

4 | THE VANIER INSTITUTE OF THE FAMILY

Why this matters

The conjugal situation of couples in Canada

has undergone a major evolution over the

generations, with an increasing shift from

marriage to common-law unions. But it

is still the most common couple type.

Understanding marriage trends is important

because these unions are the context in

which a lot of family experiences occur.

The decline in the proportion of couples

who get married does not mean that more

people are single or alone but that the

nature of these relationships has continued

to evolve alongside social, economic,

cultural, and legal changes. Marriage was

a norm because it was once seen by many

people as the only legitimate means of

forming and maintaining a family. For

many couples today, marriage is no longer

a prerequisite to living together or having

children. The growing share of common-

law unions has further diversified the

pathways people can take to form a family.

Number of marriages per 1,000 population

(crude marriage rate), Canada, 1991–2020

Source: Statistics Canada. (2022, November 14). Number

of marriages and nuptiality indicators.

3

Percentage of total population aged 15 to 49

and 50 and older in couples who were married,

Canada, 1991 and 2021

Sources: Statistics Canada. (1992). Population by age

groups (21a) and sex (3), showing marital status (6) –

Canada, provinces and territories, federal electoral districts

and enumeration areas.

7

Statistics Canada. (2023, March 29). Marital status, age

group and gender: Canada, provinces and territories and

economic regions.

1

a

What had been prohibited before 2005 was marriage between two persons of the same (legal) sex, regardless of their gender

identity/expression. As understandings of gender have evolved, Statistics Canada replaced the term “same sex” with “same gender”

in terminology related to couples and families.

FAMILIES COUNT 2024 | FAMILY STRUCTURE

5 | THE VANIER INSTITUTE OF THE FAMILY

2

In previous generations, marriage was often

seen as a precursor to family life, and for

many it still is. Since the 1970s, couples have

become less likely to marry, and a growing

proportion are choosing to live common-law.

Data show those who “tie the knot” today—

whether or not it is for the first time—are

doing so later in life.

In 2021, nearly six in 10 people in Canada

(56.9%) aged 15 and older were in married

or

common-law couples.

1

More than three-

quarters (77%) of all couples living together

in 2021 were married, down from 94% in

1981.

4

In 2020, the average age of people

who

married was 34.8 years, up 3.5 years

from 31.3 years in 1994.

8

During this period,

the

average age of those who married for

the first

time also increased, from 27.8 to

31.2 years.

Age-specific marriage rates provide

additional insights into the timing of

marriage. The rates show a decline among

all age groups over the last three decades,

particularly among people under 30.

The steepest decline in marriage rates in

Canadian history took place during 2020,

when public health measures aimed at

limiting the spread of COVID-19 closed

public gathering spaces.

4

A variety of social, demographic, and

cultural factors have contributed to couples

marrying later in life. These factors are also

driving a similar shift with the later timing

of other milestones, such as moving out

of the parental home, having children,

and buying a home. Thirty years ago, a

driving factor was the growing number

of remarriages that occurred later in life.

The liberalization of divorce laws in 1968

resulted in an increase in the number of

older people remarrying after divorcing

their former spouse

4

—marriages that

increased the average age at marriage.

Today, the growing popularity of common-

law unions has become a main driver of

later marriages.

Furthermore, more young people are

pursuing higher education and establishing

their careers before considering marriage.

Economic factors, such as high prices for

housing and postsecondary education,

make it more challenging for young couples

to save enough money to establish a

household and feel financially secure

before getting married. Many young adults

prioritize personal growth, self-discovery,

and finding the right partner before making

a long-term commitment like marriage.

Couples are marrying later

in life

2

6 | THE VANIER INSTITUTE OF THE FAMILY

FAMILIES COUNT 2024 | FAMILY STRUCTURE

Why this matters

Since marriage often came before family life

in the past, it happened at much younger

ages. Many couples today are putting off

marriage because they want to pursue

other aspirations first. Even among those

who do choose to marry, most young

people now prefer to live together with

their partners as a way of “testing the

waters” before committing to marriage,

which has pushed up the average age

at marriage. Since the risk of divorce

decreases the older one gets married,

this shift could result in longer lasting

marriages, on average.

9

Average age at marriage, by legal marital

status prior to marriage, Canada, 1994–2020

Source: Statistics Canada. (2022, November 14). Mean age

and median age at marriage, by legal marital status.

8

Marriage rate per 1,000 unmarried persons,

by age group, Canada, 1994–2020

Source: Statistics Canada. (2022, November 14). Number

of persons who married in a given year and marriage rate

per 1,000 unmarried persons, by age group and legal

marital status.

10

FAMILIES COUNT 2024 | FAMILY STRUCTURE

7 | THE VANIER INSTITUTE OF THE FAMILY

Divorce rates are influenced by social,

economic, legal, and cultural trends. From

the late 1960s to the late 1980s, the number

of divorces in Canada increased sharply.

This was driven by a variety of factors,

including decreasing stigma against divorce

and the increasing economic independence

of women. Equally important was the

creation of the Divorce Act, 1968 and

amendments made in 1986 that made

it easier to obtain a divorce. Since the

early 1990s, however, divorce rates

have declined notably.

The number of divorces has fallen since the

early 1990s, from nearly 79,000 in 1991 to

57,000 by 2019.

11

In 2020, nearly 43,000

divorces were granted in Canada—the

lowest number since 1973.This decline

was largely due to disruptions in the court-

based process of granting divorces during

the COVID-19 pandemic.

The divorce rate (i.e., the number of

persons who divorce in a given year per

1,000 married persons) also declined

during this period. This dropped from

12.7 per 1,000 married people in 1991

to 7.5 per 1,000 married people in 2019,

before hitting a record low of 5.6 per 1,000

married people in 2020 during the early

months of the pandemic.

12

The aging of the married population is key

to understanding the decline in divorce

rates over time. Divorce rates tend to

be lower among older age groups. In

2020, there were 5.2 divorces per 1,000

married persons for those aged 50 to 64,

compared with 8.5 per 1,000 among

those aged 15 to 34.

11

Although the divorce

rate is higher for younger age groups, it has

also declined in recent years.

Younger couples today tend to follow

different trajectories than previous

generations regarding marital status. In

recent decades, a growing share of younger

people have been choosing common-law

unions rather than marriage. Since divorces

apply only to married and not to common-

law unions, a decreasing proportion of

couples getting married in a population

inevitably leads to a lower number of

divorces within that population.

5

Why this matters

Divorce statistics do not provide a complet

e

picture of relationships ending. In 2021,

more than one in five (22.7%) couple

relationships in Canada were common-

law.

5

This rate continues to increase and is

much higher in some parts of the country,

Divorce rates have declined

since the early 1990s

3

8 | THE VANIER INSTITUTE OF THE FAMILY

FAMILIES COUNT 2024 | FAMILY STRUCTURE

particularly in Quebec and Nunavut. When

common-law couples end their relationship,

it is not recorded in divorce data.

Even so, divorce statistics are valuable

indicators since most couples are married,

and therefore may experience a divorce in

their lifetime. Currently, they are some

of the only statistics to show that a

relationship has ended. Understanding

these trends is important because they

provide unique insights on topics at the

heart of family life, such as fertility,

finances, housing, and caregiving.

20,000

40,000

60,000

80,000

100,000

120,000

1970

1971

1972

1973

1974

1975

1976

1977

1978

1979

1980

1981

1982

1983

1984

1985

1986

1987

1988

1989

1990

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

Number of divorces

COVID-19

public health

measures

Divorce Act

amendments (1986)

Number of divorces, Canada, 1970–2020

Source: Statistics Canada. (2022, November 14). Number of divorces and divorce indicators.

12

Number of persons who divorced per 1,000 married persons (refined divorce rate)

by age group, Canada, 1991–2020

Source: Statistics Canada. (2022, March 9). A fifty-year look at divorces in Canada, 1970 to 2020. The Daily.

11

FAMILIES COUNT 2024 | FAMILY STRUCTURE

9 | THE VANIER INSTITUTE OF THE FAMILY

Compared with previous generations, far

more couples today are choosing to live

together without getting married. Younger

generations’ shift toward living common-law

before—and sometimes instead of—getting

married may sound unremarkable today

since much of this shift occurred decades

ago. It nonetheless signifies a major shift in

what families look like and how people think

about family life.

Individuals are considered to be in a

common-law relationship when they

cohabitate for a certain period of time (this

varies by province or territory), yet they have

not formalized their union through legal

marriage.

13

In 2021, Canada was home to

more than 1.9 million common-law couples,

representing nearly one-quarter (22.7%) of

all couples.

14

This is more than triple when

they were first counted in the 1981 Census

(6.3%).

15

Among G7 countries, Canada now

has the highest percentage of couples living

common-law.

5

More than one in five people

aged 15 and older (22.1%) were living

common-law in 2021, nearly four times

higher than in 1991 (6.7%).

1, 2

Canada’s high proportion of common-

law couples is driven by the even higher

prevalence found in Quebec. In 2021, more

than four in 10 couples (42.7%) were

common-law, compared with only 16.9%

outside of Quebec.

6

In addition to having

more than double the proportion of couples

living common-law, Quebec also saw a

much higher increase over time. The highest

proportion is in Nunavut, which became

the first province or territory in the country

with a majority (51.7%) of couples living

common-law in 2021.

Living common-law is more prevalent

among younger age groups, which reflects

an ongoing generational shift. In 2021,

nearly one-quarter (23.5%) of 25- to

29-year-olds lived common-law,

1

up from

14.0% in 1991.

2

The number of people

living common-law decreases after young

adulthood older in most parts of Canada.

The two exceptions are Quebec and

Nunavut, where living common-law is

more commonly chosen as an alternative

to marriage.

5

The 2017 General Social Survey asked

common-law partners who had indicated

that they did not intend to marry their current

partner why they did not want to get married.

Among those aged 25 to 34, the top two cited

responses were that the “current situation is

fine as is” (37.8%), followed by “don’t believe

in the institution of marriage” (24.3%).

17

The growing proportion of couples choosing

common-law over marriage is driven by a

Common-law unions are most

common in Quebec and Nunavut

4

10 | THE VANIER INSTITUTE OF THE FAMILY

FAMILIES COUNT 2024 | FAMILY STRUCTURE

variety of factors, including the declining

influence of religion on society, broadened

divorce legislation, improved access to

contraception, and increasing educational

attainment and labour force participation of

women. This shift has been most pronounced

in Quebec, where the influence of the Catholic

Church has declined greatly since the 1960s.

The higher prevalence of common-law

unions in Nunavut is associated with the

characteristics of its population, which is

younger and largely Indigenous (84.3%

of its population in 2021 were Inuit

18

).

Why this matters

Many people assume that common-law

couples have the same rights as married

couples. While Canadian law has

increasingly treated both couple types the

same, their rights and obligations, as well

as the definition of “common-law,” vary

across provinces and territories. For example,

married people are eligible for spousal

support, division of property in the case of

separation and divorce, or inheritance in case

of death, but the portrait is far more complex

for people in common-law relationships. If a

common-law couple separates in Ontario,

Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince

Edward Island, Newfoundland and Labrador,

or Yukon, there is no legal obligation for

the partners to divide their property as a

married couple.

19

As couples continue to

opt for living common-law, issues such

as these may affect a growing number of

people in Canada.

19.0

42.7

8.6

16.9

11.2

22.7

1991 1996 2001 2006 2011 2016 2021

Percentage of couples

Inside Quebec Outside Quebec Canada (average)

Percentage of all couples that were

common-law, inside Quebec and outside

Quebec, 1991–2021

Sources: Statistics Canada. (2008, February 19). Number of

children at home (8) and census family structure (7) for the

census families in private households of Canada, provinces,

territories, census divisions, census subdivisions and

dissemination areas, 2006 Census – 20% sample data.

20

Statistics Canada. (2013, December 23). Number of children

at home (8) and family structure (7A) for census families in

private households, for Canada, provinces and territories,

1981 to 2001 censuses – 20% sample data.

21

Statistics Canada. (2018, May 30). Census family structure

(7) and presence and ages of children (15) for census

families in private households of Canada, provinces and

territories, census metropolitan areas and census

agglomerations, 2016 and 2011 censuses – 100% data.

22

Statistics Canada. (2022, July 13). Census family structure,

presence of children and average number of persons per

census family: Canada, provinces and territories, census

metropolitan areas and census agglomerations.

6

FAMILIES COUNT 2024 | FAMILY STRUCTURE

11 | THE VANIER INSTITUTE OF THE FAMILY

Approximately one in 10 people in Canada

are in an intimate relationship but do not

live with their partner, in what is known as

a living apart together (LAT) couple.

23

Also

known as non-cohabitation, LAT is both a

living arrangement and one of the many

forms of structural diversity found among

families in Canada. Researchers have paid

growing attention to LAT couples as couples

have become increasingly diverse and this

living arrangement becomes more common.

Data from the 2017 General Social Survey

(GSS) show that nearly 1.5 million people

aged 25 to 64 were in a couple

a

with

someone living in a different residence.

23

This accounted for 9% of all people in

couples, up from 6% in 2006. Living apart

together is most common among younger

age groups: among those in couples, 20%

of 25- to 34-year-olds, 7% of 35- to 54-

year-olds, and 5% of 55- to 64-year-olds

lived apart in 2017.

Among those in LAT couples in 2017, 15%

said that they had never considered living

together, while 34% said it was a choice to

live apart.

23

Just over half (51%) cited “other

circumstances”

b

as the reason they did not

live together, which included schooling,

financial situations, and work.

There are many reasons why couples may

choose to continue living apart, though it is

often a transitionary phase that eventually

leads to living together. According to the

2011 GSS, seven in 10 people in LAT couples

said that they intended to live together

eventually, while 15% were uncertain and

14% said they did not intend to live together

(this data is not available for 2017).

24

The

proportion who intended to live together

decreased with age, from 83% of 20- to

24-year-olds in LAT relationships to only

28% for those aged 60 and older.

a

In 2011, the most frequently cited reason

among this group for choosing to live

separately was that they were “not yet ready

for living together” (48%), indicating that

their LAT status was transitional. Nearly

three in 10 people (28%) who chose to live

in an LAT couple said they did so to “keep

independence.”

a

Why this matters

Couples living apart is by no means a new

phenomenon, although it has become more

commonplace in recent decades. LAT

couples are more frequent among young

adults as they navigate school, work, and

social life. People who have previously been

Living apart is increasingly

common among couples

5

12 | THE VANIER INSTITUTE OF THE FAMILY

FAMILIES COUNT 2024 | FAMILY STRUCTURE

married may wish to maintain financial

autonomy and avoid intertwining their

debt or wealth with a new partner, or

they may simply not feel any pressure

to live together.

Regardless of their age, many people who

choose to live apart together do so to

experience the connection and intimacy

of being in a couple while maintaining the

independence of living apart. There may

be important considerations that need

to be managed or otherwise addressed

by couples living apart, such as how

caregiving is provided across households.

25

33.4

20.2

6.2

32.8

16.8

3.9

33.8

23.1

12.1

20–34 years 35–64 years 65+ years

Percentage

Total Women Men

Proportion of the population living alone in a living apart together

(LAT) relationship, by age group and gender, Canada, 2017

Source: Tang, J., Galbraith, N., & Truong, J. (2019, March 6). Living alone in Canada.

Insights on Canadian Society.

26

a

Includes those in living-apart-together relationships who were married, single (never married), widowed, divorced, or separated.

b

A breakdown of the percentage of respondents citing these examples is not available.

FAMILIES COUNT 2024 | FAMILY STRUCTURE

13 | THE VANIER INSTITUTE OF THE FAMILY

Polyamorous families are one of the growing

number of diverse family structures in

Canada. Polyamory is a form of consensual

non-monogamy (CNM). This umbrella term

describes any type of intimate relationship

in which the partners allow sexual and/or

emotional relationships outside their

couple relationship.

27

While some of these

relationship types are focused on the partners

allowing for sexual experiences outside the

couple without romantic or emotional

attachments, polyamory is distinguished

from other CNM relationship types in that

it allows for them.

Like all relationships, polyamorous

relationships

are diverse. The specific

structures, the types of relationships

(e.g., sexual and/or romantic,

regular, or

infrequent), and the roles and expectations

within can vary greatly depending on the

preferences of the people involved. Some

polyamorous families are centred around

long-term, committed relationships

with

two or more people, while others may

have a mix of short-term and long-term

relationships with varying degrees of

intimacy and commitment.

28

Polyamorous relationships may include—but

do not require—a married or common-law

couple, but Canadian law does not recognize

intimate relationships between more than

two people. Since polyamorous relationships

are not counted in the Census nor included

in the definition of a census family household,

there is a data gap in their prevalence and

composition. Surveys have shown that

approximately one in five people in Canada

and the United States have practised

consensual non-monogamy at some point,

with young adults more likely to have done

so.

27

Research shows that sexual minorities

are more likely to practise CNM than

heterosexual people.

29

Polyamorous families are increasingly being

recognized in Canadian law. This has resulted

from legal cases in which more than two

people in a polyamorous relationship shared

parental responsibilities but faced difficulties

because their family structure was not being

recognized in most law or policies. For

example, the Divorce Act defines “spouse”

as “either of two persons who are married

to each other,” while the Civil Marriage Act

provides that marriage is “the lawful union of

two persons to the exclusion of all others.”

30

Several court cases in recent years have

broadened parental rights to also include

families with more than two parents and

addressed the exclusion of polyamorous

families from Canadian law. In 2018, three

unmarried adults in a relationship in

Newfoundland and Labrador were declared

legal parents of a child born within their

polyamorous family. Because the provincial

Polyamorous families have

broadened family law

6

FAMILIES COUNT 2024 | FAMILY STRUCTURE

14 | THE VANIER INSTITUTE OF THE FAMILY

Children’s Law Act did not allow for more than

two people to be named as the legal parents

of a child, only two could be listed on the

child’s birth certificate. In his ruling, Justice

Robert Fowler of the Newfoundland and

Labrador Supreme Court’s family division

said that “Society is continuously changing

and family structures are changing along

with it.

31

This must be recognized as a

reality and not as a detriment to the best

interests

of the child.”

In 2021, a British Columbia court ruled that

a second mother in a polyamorous family be

added to a child’s birth certificate. Justice

Sandra Wilkinson echoed Fowler’s ruling,

stating “I find that there is a gap in the [Family

Law Act

32

]... Put bluntly, the legislature did not

contemplate polyamorous families.” She said

that it was in the “best interests [of the child]

to have all of his parents legally recognized

as such.”

Why this matters

This lack of alignment between the diversity

of families and the laws that affect them can

have an impact on wellbeing; these families

often must navigate and interact with systems

and institutions that were not designed to

support them. This was underscored in a

2021

study in which polyamorous parents

in Canada who had recently given birth (or

been a partner to someone who did) reported

experiencing conflict with, or exclusion from,

aspects of social systems designed for

monogamous couples/families.

33

Other research shows that parents in

polyamorous families also report challenges

and difficulties regarding parenting and family

dynamics, including social acceptance and

legal protection, coming out to children,

time management, and reconciling family

obligations with personal needs.

27

Some

of these issues may dissipate in future

generations if greater awareness and

discussion act to reduce stigma and/or

if family law continues to become more

inclusive of diverse family structures. Many

parents in polyamorous families also cited

strengths of their family structure, such

as having a larger support network for

themselves and their children.

Despite the small body of research on

polyamorous families in Canada, there

is growing awareness and discussion of

non-traditional relationship types, including

polyamory and other forms of consensual

non-monogamy. Polyamorous families are just

one of many forms of structural diversity that

make families unique. The struggles for legal

recognition of parents in these families

highlight how laws and policies often trail

social change. It remains to be seen how

these developments may reshape or

otherwise impact family justice policies,

legislation, and training for service providers.

34

Further research will play an important role in

strengthening understanding of polyamorous

families and ensuring they are included in

laws and policies.

Different versions of the pride flag, designed by Red Howell

in 2022 (left),

35

and by Jim Evans in 1995 (right).

36

FAMILIES COUNT 2024 | FAMILY STRUCTURE

15 | THE VANIER INSTITUTE OF THE FAMILY

Young adults have become more likely to

live with parents over the last 30 years.

Census data show that, in 2021, nearly half

(45.8%) of those aged 20 to 29 lived with

at least one parent.

37

Living with parents

into young adulthood is done out of

neccessity, out of preference, or both.

38

In 1991, 32.1% of those in their twenties

lived with parents.

39

This includes both

young adults who never left and those

who returned home after living elsewhere.

As was the case 30 years ago, men were

more likely than women in their twenties to

live with parents in 2021 (49.4% vs. 42.0%,

respectively).

37

Men (64.6%) and women

(59.3%) aged 20 to 24 were more likely to

live with parents than those aged 25 to 29

(35.2% and 26.7%, respectively).

Across provinces and territories, the highest

percentages of people in their twenties

living with parents in 2021 were in Nunavut

(54.7%) and Ontario (53.3%).

37

These

were the only provinces/territories above

the national average. Living with parents

was least commonly reported among those

living in the Yukon (33.8%), Nova Scotia

(36.4%), and Saskatchewan (36.9%).

Several factors contribute to these

geographical differences. Housing often

plays a role. The availability and adequacy

of housing has been a long-standing issue

in Nunavut, for example, where the highest

percentage of young adults live with parents.

In large urban centres like Vancouver and

Toronto, the cost of renting or buying a

home is a driving factor for young adults

living with parents.

Compared with rural areas, large urban

centres are also home to a greater proportion

of immigrant families, who are more likely

to live with parents.

38

Data from the 2011

National Household Survey showed that

immigrant young adults in their twenties

were more likely than non-immigrants to

live with their parents (50% vs. 42%).

39

Why this matters

Living with a parent can be a valuable source

of emotional, logistical, and financial support

.

This is especially true when pursuing

education, after a relationship break-up

or separation, when there are fewer job

opportunities, or when there are economic

disruptions. Living with parents can be a

strategy for dealing with low employment

earnings, job loss, or the high cost of living.

Others may choose this living arrangement

to provide or receive care across generations.

Young adults are more likely

to live with parents

7

FAMILIES COUNT 2024 | FAMILY STRUCTURE

16 | THE VANIER INSTITUTE OF THE FAMILY

Indeed, the most recent data on the topic

show that, in 2012, 9.0% of young adults

aged 20 to 34 who were usually living with

their parent(s) were the primary caregiver

for one or both parents.

40

Several factors may explain the increase in

the number of young adults living with their

parents, including the higher percentage of

young people now pursuing postsecondary

education, whose student debt often

results in greater economic dependence.

Living with a parent also does not come

with the same stigma it used to in

previous

generations, which removes

a social deterrent

from choosing this

living arrangement.

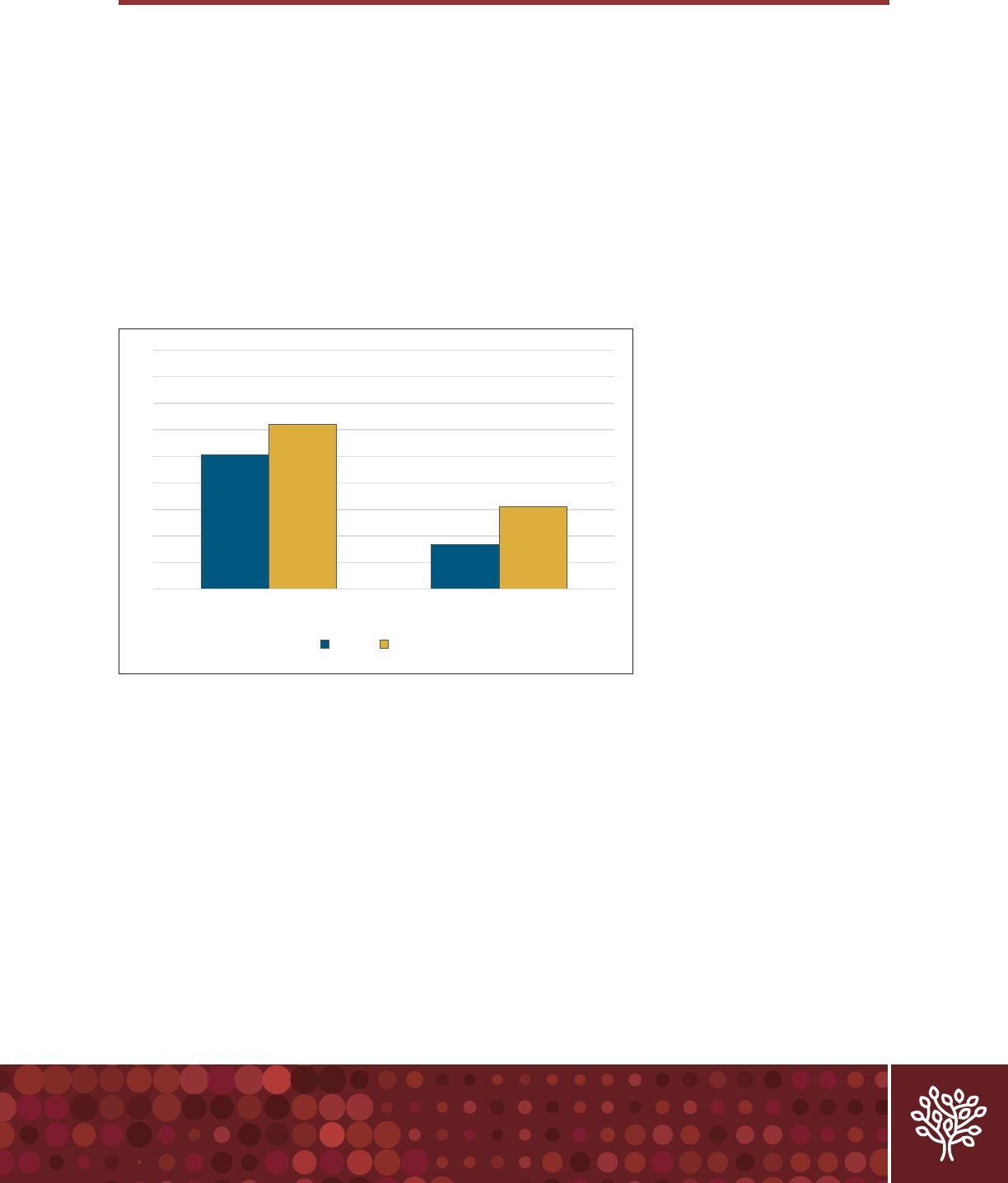

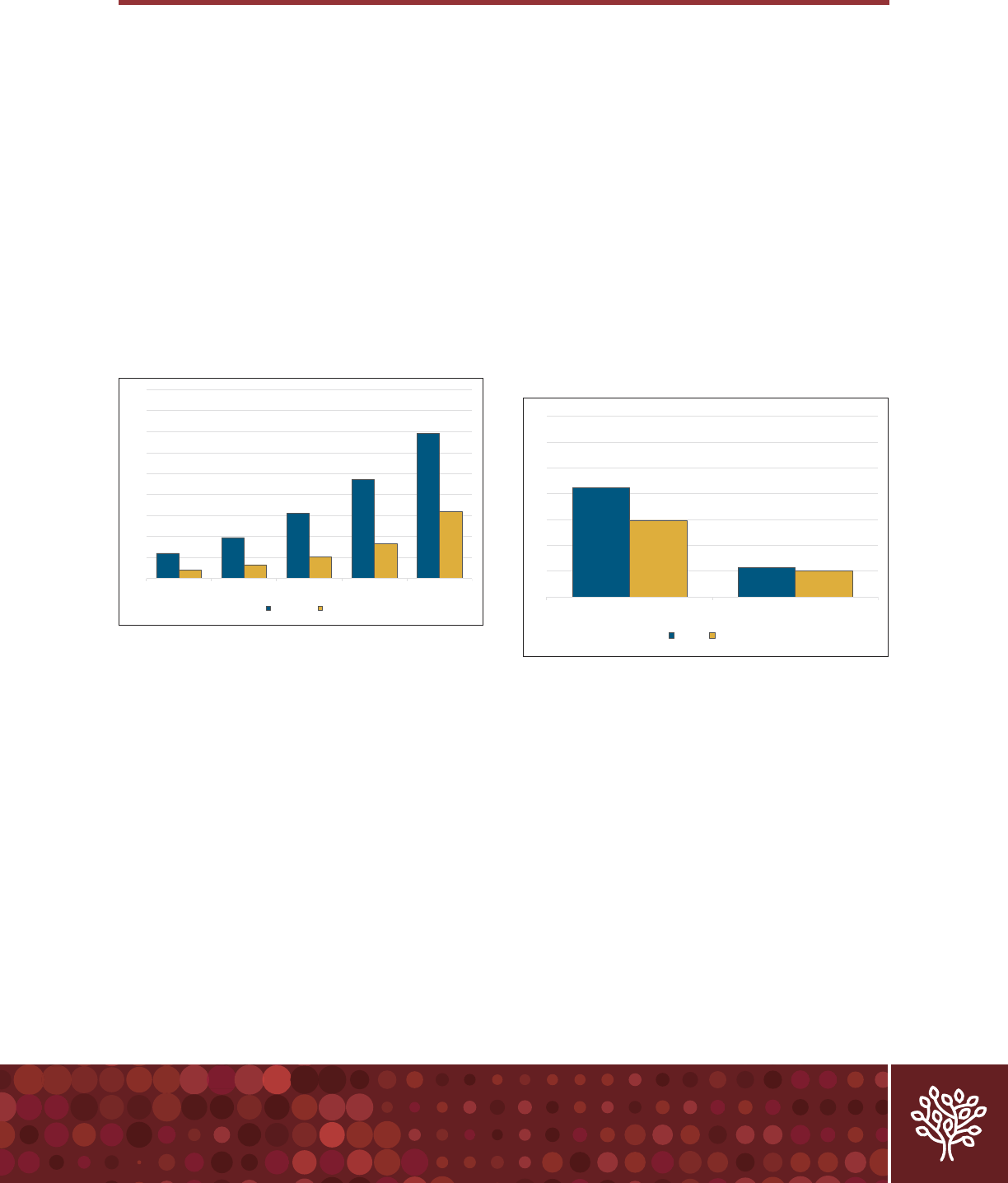

50.5

16.9

62.0

31.0

20–24 years 25–29 years

Percentage

1991 2021

Percentage of the population aged 20 to 29 living with at least

one parent, by age group, Canada, 1991 and 2021

Sources: Milan, A. (2016, June 15). Diversity of young adults living with their

parents. Insights on Canadian Society.

39

Statistics Canada. (2022, July 13). Census family status and household living

arrangements, presence of parent in household, age group and gender: Canada,

provinces and territories, census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations.

37

FAMILIES COUNT 2024 | FAMILY STRUCTURE

17 | THE VANIER INSTITUTE OF THE FAMILY

Multigenerational households (those

housing three or more generations) have

never been a dominant living arrangement

in Canada. However, they have become one

of the fastest

growing household types in

recent decades

.

In 2021, there were more than 442,000

multigenerational households in Canada,

41

home to 2.4 million people, or 6.4% of the

total population.

42

These households have

grown in number by 21.2% since 2011—

much higher than the overall increase of

12.4% observed among all households.

41

A growing share of children under 15 are

living with grandparents, from 8.5% in 2011

to 9.1% in 2021 (93.3% of whom were living

in multigenerational households).

42

Data from the 2021 Census show that

Indigenous and immigrant families—

two fast-growing population groups—

are more likely than others to live in

multigenerational households. Provinces

and territories with relatively higher

proportions of Indigenous and/or immigrant

children under 15 had the highest percentage

of children who lived with grandparents.

This included Nunavut (21.3%), British

Columbia (13.1%), Ontario (11.8%), and

the Northwest Territories (9.4%).

43

Census

metropolitan areas

a

with the highest

proportion of multigenerational households

were also home to some of the highest

percentages of immigrants in the country,

such as in Abbotsford-Mission (22%),

Brampton (28%), and Markham (23%).

Among children under age five, 10.4% lived

with at least one grandparent in 2021.

43

This proportion was more than twice as

high among First Nations (19.7%) and

Inuit (24.6%) children than among non-

Indigenous children (9.8%). Among the

Métis children in this age group, 9.4% lived

with at least one grandparent.

The higher likelihood of living in a

multigenerational household also

reflects the fewer options immigrant and

Indigenous families may have to choose

from. Most immigrant families first arrive

in major urban centres, which also tend to

have the highest housing prices. In 2021,

multigenerational households were the

most common living arrangement among

First Nations people living in crowded

housing (34.5%).

44

Multigenerational households

are one of the fastest growing

household types

8

FAMILIES COUNT 2024 | FAMILY STRUCTURE

18 | THE VANIER INSTITUTE OF THE FAMILY

Why this matters

Some families live in multigenerational

households because it can help with care

and caregiving between generations.

Multigenerational households often include

someone with an activity limitation.

45

In

addition, many grandparents who live with their

grandchildren provide care when the parents

are at work, at school, or running errands. This

can help families with certain childcare costs,

something with which many parents struggle.

There are many complex reasons for the

increase in multigenerational households.

Through income-pooling, the cost-saving

advantages in these households can

be important for recent immigrants

and their families as they adapt to

their new country and build connections.

Some families may also already have a

cultural preference for living with multiple

generations. Families from all backgrounds

may also choose to live in multigenerational

households when they include new and

expectant parents.

Even so, multigenerational living is not

for everyone, and living with multiple

generations sometimes happens out

of necessity, not choice. This can result

in unsuitable living arrangements, such

as crowded housing, which is known

to affect wellbeing.

46

a

A census metropolitan area is a large urban centre with a population of at least 100,000 with 50% living in the core.

PE

Percentage of the population living in a multigenerational household, Canada, 2021

Source: Statistics Canada. (2022, July 13). Census family status and household living arrangements, household type of person,

age group and gender: Canada, provinces and territories, census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations.

42

FAMILIES COUNT 2024 | FAMILY STRUCTURE

19 | THE VANIER INSTITUTE OF THE FAMILY

Stepfamilies have always been a part

of Canada’s family landscape, but the

circumstances leading to their formation

have changed across generations. Similar

to a shift that has occurred among

one-parent families, stepfamilies used to

typically form after the death of a spouse

or partner. In today’s context of relatively

higher divorce rates and lower mortality

(particularly maternal mortality),

they now usually form after divorce

or separation.

47

The 2021 Census data showed there

were more than 500,000 stepfamilies in

Canada.

48

A stepfamily is a couple family

with children that contains at least one

child (biological or adopted) of only one

of the spouses/partners whose birth

or adoption preceded the current

relationship. The spouses/partners in

stepfamilies can be married or living

common-law.

In 2021, 8.4% of all couple families with

children of any age were stepfamilies,

down slightly from 9.0% in 2011.

48

Nearly

four in 10 (39%) same-gender couples

with children of any age in 2021 were

stepfamilies, compared with 12% of

different-gender couples with children.

5

Stepsiblings are defined in the Census as

siblings who live in the same household

but do not have the same birth or adoptive

parents. Half-siblings, on the other hand,

are siblings who live in the same household

and share one common birth or adoptive

parent.

a

In 2021, approximately two-thirds

(65.2%) of children aged 0 to 14 in

stepfamilies had at least one half- or

stepsibling.

38

The remaining 37.5%

had neither.

Among couples with children, those living

in a common-law relationship in 2021

were more than four times as likely to

be stepfamilies (31.0%) as their married

counterparts with children (7.3%).

48

This

suggests that parents may prefer to live

common-law when they re-partner.

Why this matters

Becoming a stepfamily is a significant life

change that affects all family members.

Spouses or partners take on the role of

stepparents, children gain new siblings,

and a relocation to a different home

often occurs. As the family adapts,

responsibilities and relationships undergo

transformation, and it may take several

Pathways to becoming a

stepfamily have evolved

9

FAMILIES COUNT 2024 | FAMILY STRUCTURE

20 | THE VANIER INSTITUTE OF THE FAMILY

years for the stepfamily to identify as

a unified family.

In the past, stepparents were often

depicted negatively in popular culture and

folklore, portraying them as wicked figures

who mistreated their stepchildren. The

image of the stepparent has undergone a

significant transformation over the years,

evolving from a negative stereotype to

being recognized as a valued second parent.

Despite this shift, policy makers and courts

are still grappling with the complexities that

stepfamilies present, especially around the

rights and responsibilities of stepparents.

a

In this context, adoptive children are treated the same as biological children.

With no stepsiblings

or half-siblings

34.8%

With at least one

stepsibling or half-sibling

65.2%

With a

stepmother

10.3%

With a stepfather

19.1%

With a stepmother

15.2%

With a stepfather

19.6%

With two biological or

adoptive parents

35.8%

Living arrangements of children under 15 living

in stepfamilies, Canada, 2021

Statistics Canada. (2022, July 13). Home alone: More

persons living solo than ever before, but roomies the

fastest growing household type. The Daily.

38

0–4 years

15.0%

5–9 years

20.4%

10–14 years

25.8%

15–24 years

38.8%

Distribution of children under 15 living in

stepfamiles, by age group, Canada, 2021

Statistics Canada. (2022, July 13). Home alone: More

persons living solo than ever before, but roomies the fastest

growing household type. The Daily.

38

FAMILIES COUNT 2024 | FAMILY STRUCTURE

21 | THE VANIER INSTITUTE OF THE FAMILY

Women in Canada now have fewer

children on average than in past

generations. This shift can be seen in the

decline in the total fertility rate (average

number of children per woman) over the

past half-century. After reaching an all-

time high of 3.94 children per woman in

1959

50

during the peak of the baby boom,

the total fertility rate (TFR) declined

sharply until the late 1980s.

51

It then

fluctuated over the next 20 years until

starting another long-term decline in

2009 that continues to this day (except

for a small temporary increase in 2021).

The most recent data show a new record

low was reached in 2022 at 1.33 children

per woman.

The reasons for this long-term decline

are complex. They include the growing

participation of women in higher education

and in the paid labour force, increased

effectiveness and availability of contraception,

and the decreased influence of religion on

daily life.

50

The percentage of women aged

25 to 54 with a postsecondary certificate/

diploma more than doubled from 28.3%

in 1990

52

to 74.5% in 2021.

53

During the

same period, the labour force participation

rate of women aged 25 to 54 increased

from 75.5% to 84.2%.

54

People’s decisions about childbearing can

be affected by the uncertainty resulting

from major events or changes in broader

social, political, environmental, or health

circumstances. For example, survey data

from April to June 2021 showed that 23.5%

of the population aged 15 to 49 changed

their fertility plans because of the COVID-19

pandemic.

55

Nearly one in five (19.2%) said

they now wanted to have fewer children

than previously planned, or to have a

baby later than previously planned.

Declining fertility rates also coincide with

changing patterns in the age of mothers.

50

The average age of first-time mothers

increased from 26.2 years in 1994 to a

record high of 29.4 years in 2019.

56

While

age at first birth declined for all age groups

under 30, it increased for those aged 30

and older.

50

Meanwhile, fertility among

young women aged 15 to 19 dropped

from 25.1 per 1,000 live births in 1994

to 4.4 per 1,000 live births by 2022.

51

Fertility rates vary across the country. Since

it was created in 1999, Nunavut had had

the highest total fertility rate in Canada

(2.23 children per woman in 2022), followed

by Saskatchewan (1.69), Northwest

Territories, and Quebec (1.49 each).

51

Fertility rates hit a record

low (again)

10

FAMILIES COUNT 2024 | FAMILY STRUCTURE

22 | THE VANIER INSTITUTE OF THE FAMILY

The lowest fertility rates in 2022 were in

British Columbia (1.11) and Nova Scotia

(1.18).

Why this matters

Policymakers and researchers closely

monitor fertility rates because major shifts

can affect families, the labour market, and

the economy. For families, fewer children

mean there are fewer people to provide

care and support within and across

generations. It also means that

intergenerational transfers of wealth

(e.g., inheritances, family support for

major life expenses, etc.) could be

increasingly concentrated in fewer hands

in the coming years.

Smaller numbers of babies being born will

result in fewer workers entering the labour

market in the future. Therefore, the labour

market could become increasingly reliant

on immigration to maintain a balance of

older and younger workers. Tracking

fertility rates can inform long-term policy

and program development, such as

immigration targets, family allowances,

subsidized childcare, pension plans,

and compassionate care benefits.

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

1.2

1.4

1.6

1.8

2.0

2.2

2.4

Total fertility rate

Average number of children per woman (total fertility rate), Canada, 1972–2022

Sources: Statistics Canada. (2018, May 17). Fertility: Fewer children, older moms. Canadian Megatrends.

50

Statistics Canada. (2023, September 27). Crude birth rate, age-specific fertility rates and total fertility rate (live births).

51

FAMILIES COUNT 2024 | FAMILY STRUCTURE

23 | THE VANIER INSTITUTE OF THE FAMILY

One-parent families are more common

than they were 30 years ago, but their

growth has stabilized over the last decade.

Also known as lone-parent, single-parent,

and solo-parent families, their prevalence

has fluctuated throughout Canada’s

history due to shifting social, economic,

and cultural factors.

In 2021, one-parent families represented

16.4% of census families.

6

This is up from

1991 (13.0%), although the proportion has

been stable since 2011 (16.3%).

57

In 2001,

part of the increase was the result of a

change in the definition of the census

family used for that census questionnaire

(and all since).

58

The highest proportion of one-parent

families in 2021 was in Nunavut (33.1%) and

the Northwest Territories (23.4%), while the

lowest was in British Columbia (14.9%).

48

That year, nearly one in five children

under 15 across Canada (19%) lived in

a one-parent family.

38

Most parents in one-parent families are

women (77.2% in 2021).

48

Even so, the

proportion that are fathers has increased

in recent decades, from 17.3% in 1991

59

to

22.8% in 2021.

48

This is similar across the

country, except in Quebec (26.0%) and

in the territories, where the proportion of

fathers in one-parent families was 30.4%

in Nunavut and 26.8% in Yukon and the

Northwest Territories.

One-parent families are not new, but their

circumstances have changed over time. In

th

e early 20th century, the most common

pathway to becoming a one-parent family was

through the death of a parent. As mortality

rates declined across generations, so did

the prevalence of one-parent families.

57

The creation of the Divorce Act, 1968, along

with amendments to the Act in 1986, made

it easier to divorce. Both contributed to

spikes in the growth rate of one-parent

families. Before these reforms—and when

marriage rates peaked immediately

following Canada’s baby boom—one-

parent families represented a record-low

8.2% of census families in 1966.

57

Women’s increasing labour force

participation also strengthened mothers’

abilities to raise children on their own.

Fathers represent a

growing share of parents

in one-parent families

11

FAMILIES COUNT 2024 | FAMILY STRUCTURE

24 | THE VANIER INSTITUTE OF THE FAMILY

Why this matters

One-parent families have always been

a part of Canada’s family landscape, as

families transition out of being couple

families following divorce or the death

of a partner. Sometimes they result from

a conscious choice to raise a child or

children without another parent, although

there is no Canadian data on this topic.

Poverty is a notable concern for

one-parent families. They often face

economic challenges due to only having

one earner, along with the financial

responsibilities of raising children. Many

face difficulties accessing affordable

housing and childcare.

60

One-parent

families with children aged 5 and

under are approximately five times more

likely than couples with children of the

same age to experience poverty.

61

To lessen financial hardship among one-

parent families, federal and provincial

governments have implemented social

support programs such as income

assistance, childcare subsidies, and tax

benefits. Following this, poverty rates for

individuals living in one-parent families

led by a woman with a child aged five and

under decreased from 62.7% in 2015 to

31.3% in 2020.

61

Still, even in 2020, the

poverty rate for parents in one-parent

families with young children was much

higher than for couple families.

82.7

77.2

17.3

22.8

1991 2021

Percentage

Mothers Fathers

One-parent families led by mothers and

fathers, Canada, 1991 and 2021

Sources: Statistics Canada. (1996). Census families in private

households by age groups of youngest never-married child

at home (10), showing family structure (7), for Canada,

provinces, territories and census metropolitan areas, 1991

and 1996 censuses (20% sample data).

59

Statistics Canada. (2022, July 13). Census family structure

including detailed information on stepfamilies, number of

children, average number of children and age of youngest

child: Canada, provinces and territories, census metropolitan

areas and census agglomerations.

48

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

1961 1971 1981 1991 2001 2011 2021

Percentage

Divorce Act, 1968

Divorce Act

amendment

(1986)

Percentage of all census families that were

one-parent families, Canada, 1961–2021

Source: Statistics Canada. (2012, September). Fifty years of

families in Canada: 1961 to 2011. 2011 Analytical products.

57

Statistics Canada. (2022, July 13). Census family structure

including detailed information on stepfamilies, number of

children, average number of children and age of youngest

child: Canada, provinces and territories, census metropolitan

areas and census agglomerations.

48

FAMILIES COUNT 2024 | FAMILY STRUCTURE

25 | THE VANIER INSTITUTE OF THE FAMILY

According to the Children’s Aid Foundation

of Canada, approximately 2,000 children

under the care of child welfare agencies in

Canada find a new home with an adoptive

family every year.

62

Adopted children often

gain new siblings, with data from the 2011

General Social Survey (the most recently

available data on the topic) showing that

the majority (59%) of adoptive parents also

had at least one biological child.

63

Legally, adoption ends the responsibilities

of birth parents toward their child and

replaces them with new legal bonds

connecting the child to the adoptive

parents. Adoptions can occur whether

the birth parents and adoptive parents

live in the same province or territory,

across different provinces or territories,

or between Canada and another country

through an international adoption.

There are three main pathways to adopt

a child that was born in Canada. The first

option is through the public child welfare

system, which finds homes for children who

are in permanent government care. This is

available in all provinces and territories and

is publicly funded. Children undergoing this

process often come from foster care.

Alternatively, some children are adopted

through private adoption agencies, which

connect the birth parent(s) with people who

wish to adopt. Currently only available in

British Columbia,

64

Alberta,

65

Manitoba,

66

and Ontario,

67

private adoptions are

not publicly funded and typically cost

several thousands of dollars. Lastly, in

New Brunswick,

68

biological parents

can actively participate in finding an

adoptive family for their child.

The adoption pathway is different in

Indigenous communities, where “custom

adoptions” are frequent. Custom adoption

is the cultural practice by which birth parents

and adoptive parents make arrangements

directly with each other, without involving

an adoption agency. By its nature, customary

adoption varies from one community to

another, but it is common for biological

parents to maintain a role in the child’s

life after adoption.

68

A detailed national portrait of adoption in

Canada is difficult because child welfare

works differently across provinces and

territories. The same is true for international

adoptions, with adoption criteria varying

from one province or territory to another.

69

Thousands of children are

adopted every year but far

more need homes

12

FAMILIES COUNT 2024 | FAMILY STRUCTURE

26 | THE VANIER INSTITUTE OF THE FAMILY

Currently, only Quebec maintains centralized

data on both provincial and international

adoptions in the province.

a

One reason for

this distinction is that since 2006, Quebec

has provided adoption-specific benefits

through the Quebec Parental Insurance Plan

(QPIP). Until 2024, these particular benefits

for adoptive parents were not available in

other provinces and territories.

Why this matters

Adoptive families in Canada play an

important role in helping children in need

with stable, caring environments. While this

makes a major difference to the lives of the

2,000 children who find new homes every

year, they represent fewer than one in 10

of the 30,000 children who are eligible for

permanent adoption.

62

But this is only the

tip of the iceberg, as more than 63,000

children overall are in government care,

and an estimated 235,000 children and

youth across the country are considered

at risk of entering care due to unstable

family situations.

The needs of adoptive families and the

adopted children are likely to vary

depending on whether the adoption

process involves family members or an

agency, or is international. Since 2010,

the number of international adoptions in

Quebec has declined, hitting a historical

low in 2020 due to the border closures

in place during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In contrast, the number of adoptions

within Quebec has remained relatively

stable since 2006.

70

In Quebec, biological and adoptive parents

are eligible for the same number of weeks

of parental benefits. Outside Quebec, until

2024, the federal benefits system provided

longer paid leave for biological parents

than for adoptive parents. This inequality

was due to the fact that maternity benefits

were intended only for the birthing parent

to support their recovery from pregnancy

and childbirth. This disparity in benefits put

adoptive families at a disadvantage. Some

adopted children may have experienced a

difficult situation prior to adoption, which

can affect the time needed to bond with

their adoptive parents and/or the need

to access additional resources to meet

special physical, developmental, and

emotional needs.

71

a

The data are only for adoptive parents who have claimed adoption benefits and are likely to underestimate the number of adopted children.

Number of adoptions

Quebec International

Number of adoptions resulting in QPIP benefits,

by adoption type, Quebec, 2006–2020

Source: Conseil de gestion de l’assurance parentale. (2022,

October). Profil des prestataires 2020.

70

FAMILIES COUNT 2024 | FAMILY STRUCTURE

27 | THE VANIER INSTITUTE OF THE FAMILY

Out-of-home care (i.e., fostering)

provides

children in difficult situations with temporary

support when they are not able to remain in

their family home. This includes

children

who have experienced neglect, abuse, or

trouble with the law.

Depending on the circumstances, time

spent in foster care may range from a brief

period to a more extended arrangement.

Foster families receive compensation

for caring for the child, but they are not

considered to be the child’s legal guardians.

Child welfare is a provincial responsibility.

There is no centralized system tracking the

number of children in foster care across

jurisdictions, where definitions, reporting

methods, and inclusion criteria often vary.

The 2021 Census counted 26,680 foster

children under age 15 in Canada.

72

This

represents about one in 250 children

under 15. Still, the census does not provide

a complete picture of children in out-of-

home care. It does not collect information

on children in other placement situations,

such as group care, treatment care, or

adoption services.

In 2021, Indigenous children accounted for

7.7% of children under 15 but for more than

half (53.8%) of all foster children.

73

Among

all children in Canada under 15, Indigenous

children were about 14 times more likely

than non-Indigenous children to be in

foster care (3.2% and 0.2%, respectively).

74

Foster children are most common in

provinces and territories with relatively

large proportions Indigenous populations.

For example, Manitoba had the highest rate

of children under 15 in foster care at a rate

of 19.7 per 1,000 children and PEI had the

lowest (1.7 per 1,000 children).

75

While there

is less data available on racialized children,

Black children are also overrepresented

among children admitted into care, which

is 2.2 times higher than their proportion

among all children.

76

Why this matters

The high rate of Indigenous children in foster

care in many ways mirrors the practices and

outcomes of the “Sixties Scoop.”

77

This refers

to a period when the Canadian government

was removing many Indigenous children

from their families and communities without

notice or consent under the guise of “child

welfare.” These children were then placed

with mostly White, middle-class families,

typically devoid of cultural understanding

around differing child rearing practices—

Half of children in foster care

are Indigenous

13

FAMILIES COUNT 2024 | FAMILY STRUCTURE

28 | THE VANIER INSTITUTE OF THE FAMILY

an extension of racist policies that sought

to assimilate Indigenous people.

76

The practice of removing Indigenous children

from their families continues at high rates

today, which has led many to call modern

child welfare practices the “Millennium

Scoop.” Similar to the residential school

system, this practice uproots children from

their families and communities, and away

from loving child-rearing practices, parental

role models, their cultures, and their identities.

Some steps have been taken to reduce the

number of Indigenous children and youth

in care. Developed in consultation with

Indigenous peoples, the 2019 Act respecting

First Nations, Inuit and Métis children,

youth and families

73

affirms the rights of

Indigenous peoples to exercise jurisdiction

over child and family services. It also allows

Indigenous groups, who wish to do so, to

design and deliver child and family services

solutions that best suit their needs.

Rate per 1,000 children

Rate of children under 15 in foster care, Canada, provinces and territories, 2021

Source: Black, T., Trocmé, N., Fallon, B., & Houston, E. (2022). Children in foster care in Canada in 2016 & 2021.

75

FAMILIES COUNT 2024 | FAMILY STRUCTURE

29 | THE VANIER INSTITUTE OF THE FAMILY

When the first edition of Families Count was

published in 1994, the most recent census

data showed that one-third (33.0%) of the

population in Canada aged 65 and older were

widowed in 1991.

7

By 2021, this had fallen to

one in five (20.0%).

1

Across all age groups,

there are proportionally fewer people who

are widowed today than in the early 1990s.

A variety of factors have driven the decline in

the proportion of widowed people and for the

tendency for widowhood to occur later in life.

Improved healthcare and advances in medical

science have contributed to increased life

expectancy. Declining crude mortality rates

over the last half century (i.e., the number

of deaths in a given year per 100,000

population) have also reduced the likelihood

of a spouse dying at a younger age.

78

The declining likelihood of becoming widowed

over the last 30 years has been most evident

among older women. This is the result of the

closing gender gap in life expectancy over the

last several decades. Between 1980–1982 and

2020–2022, life expectancy at birth increased

from 79.1 years to 83.8 years for women, and

from 72.0 years to 79.3 years among men.

79

As a result, the gap in life expectancy between

women and men fell from 7.1 years to

4.5 years during this period.

In 2021, 47.1% of women aged 80 to 84

were widowed, compared with 16.6% of

men in the same age group.

1

It is not until

men reach 95 years of age and older that

most are widowed. Also, men tend to be

older than women in most heterosexual

marriages, and the average age difference

between spouses or partners has reduced

in recent decades.

80

This has contributed to

the declining percentage of widowed

people—particularly women.

Another contributing factor is declining

marriage rates. “Widowed” includes people

whose legally married spouse has died and

who have not remarried. Common-law

families are therefore not included in

widowhood statistics, because the

partners were never legally married.

Why this matters

In addition to feelings of grief, sadness,

and loneliness, being widowed can have

major consequences for the grieving

partners and their families. Widowhood

has economic implications, since it is often

accompanied by additional expenses, such

as funeral costs and expenses related to

changes in living arrangements. Losing a

spouse also often means losing a source

The percentage of older adults

who are widowed has declined

14

FAMILIES COUNT 2024 | FAMILY STRUCTURE

30 | THE VANIER INSTITUTE OF THE FAMILY

of family income, particularly for older

people who may have limited workforce

opportunities and/or who had relied

on their spouses’ income or pension

benefits. For younger families, the

surviving spouse may experience

difficulties in combining earning and

caregiving responsibilities while adjusting

to changing family dynamics during a

difficult time.

Various programs and initiatives are in

place to support the economic wellbeing of

widowed people, including survivor benefits

through the Canada Pension Plan (CPP) and

Old Age Security (OAS) programs. These

programs have helped to improve the

living standard of widowed older adults.

Research has shown that divorce has a

greater impact on living standards than

widowhood during retirement.

81

12.1

19.5

31.1

47.1

69.2

4.0

6.6

10.4

16.6

31.9

65–69 years 70–74 years 75–79 years 80–84 years 85+ years

Percentage

Women Men

Percentage of older adults who were widowed,

by gender and age group, Canada, 2021

Source: Statistics Canada. (2023, March 29). Marital

status, age group and gender: Canada, provinces and

territories and economic regions.

1

42.4

11.4

29.8

10.1

Women Men

Percentage

1991 2021

Percentage of the population aged 65 and

older who were widowed, by gender, Canada,

1991 and 2021

Sources: Statistics Canada. (1992). Population by age groups

(21a) and sex (3), showing marital status (6) – Canada,

provinces and territories, federal electoral districts and

enumeration areas.

7

Statistics Canada. (2023, March 29). Marital status, age

group and gender: Canada, provinces and territories and

economic regions.

1

FAMILIES COUNT 2024 | FAMILY STRUCTURE

31 | THE VANIER INSTITUTE OF THE FAMILY

References

1

Statistics Canada. (2023, March 29). Table 98-10-0132-01 Marital status, age group and gender: Canada, provinces and

territories and economic regions.

https://doi.org/10.25318/9810013201-eng

2

Statistics Canada. (1993, June 1). Table 97-570-X1991003 Population by age groups (21a) and sex (3), showing marital

status (6) – Canada, provinces and territories, census divisions and census subdivisions.

https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/catalogue/97-570-X1991003

3