Selected Statistics on

Canadian Families and

Family Law:

Second Edition

Prepared by:

Research Unit

Child Support Team

Department of Justice Canada

Aussi disponible en français

This report may be reproduced, in part or in whole, and by any means, without charge or further

permission from the Department of Justice, provided that due diligence is exercised in ensuring

the accuracy of the materials reproduced; that the Department of Justice is identified as the

source department; and that the reproduction is not represented as an official version of the

original report.

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, (2000)

(Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada)

- i -

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION...........................................................................................................................1

FAMILY DEMOGRAPHICS .........................................................................................................2

Family Type .............................................................................................................................2

Families with Children.............................................................................................................2

Family Context at Birth............................................................................................................3

Lone-Parent Families ...............................................................................................................4

Family Income..........................................................................................................................5

Family Poverty.........................................................................................................................6

MARRIAGE, DIVORCE AND SEPARATION.............................................................................8

Marriage...................................................................................................................................8

Divorce.....................................................................................................................................8

Trends in Marriage and Divorce ..............................................................................................9

Duration of Marriage and Age at Time of Divorce................................................................10

CHILDREN AND SEPARATION AND DIVORCE...................................................................11

The Complex Family Lives of Canadian Children ................................................................11

Children from Broken Families Come Disproportionately

from Common-Law Unions...................................................................................................12

Patterns of Separation and Divorce........................................................................................13

CHILD CUSTODY.......................................................................................................................15

Custody Arrangements...........................................................................................................15

Existence of Court Orders for Custody and Variations

by Time Since Separation and Type of Separation................................................................15

Custody .................................................................................................................................. 15

Living Arrangements..............................................................................................................17

Contact with Non-custodial Parent ........................................................................................17

Contact with Non-custodial Parent over Time....................................................................... 19

CHILD AND SPOUSAL SUPPORT PAYMENTS .....................................................................21

Number of People Paying and Receiving Support between 1986 and 1996..........................21

Income Levels of Payers and Recipients of Child Support....................................................22

Sources of Income..................................................................................................................23

Child Support Arrangements..................................................................................................25

Regularity of Payments ..........................................................................................................26

Visiting Patterns and Payment of Child Support ...................................................................26

- ii -

APPENDIX ...................................................................................................................................28

STATISTICS CANADA SURVEYS............................................................................................28

National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth (NLSCY) ..........................................28

Central Registry of Divorce Proceedings (CRDP).................................................................28

Survey of Labour Income Dynamics (SLID) .........................................................................28

REVENUE CANADA DATA......................................................................................................28

Tax Statistics..........................................................................................................................28

BIBLIOGRAPHY .........................................................................................................................29

- iii -

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1: Average Annual Income by Family Type, 1993-1997 ....................................................6

Table 2: Families and Poverty (1996) ...........................................................................................7

Table 3: Number and Rate of Marriages and Divorces,

Canada and Provinces/Territories, 1997 .........................................................................8

Table 4: Distribution of Children According to Whether a

Court Order for Custody Exists, by Type of Broken Union and

Time Elapsed Since Separation—NLSCY, Cycle 1, 1994-1995 ..................................15

Table 5: Court-Ordered Custody Arrangement, According to

the Age of the Child at Separation and

the Type of Broken Union—NLSCY, Cycle 1, 1994-1995 ..........................................16

Table 6: Living Arrangements at Time of Separation for

Children of Broken Families—NLSCY, Cycle 1, 1994-1995......................................17

Table 7: Type of Contact Maintained With Either Parent at Time of Separation

by Type of Union—NLSCY, Cycle 1, 1994-1995........................................................19

Table 8: Type of Support Agreement According to

Type of Broken Union—NLSCY, Cycle 1, 1994-1995 ................................................25

Table 9: Type of Support Agreement and Regularity of Payments,

According to Type of Broken Union—NLSCY, Cycle 1, 1994-1995 ..........................26

- iv -

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1: Family Type as a Proportion of all Families (1996)....................................................2

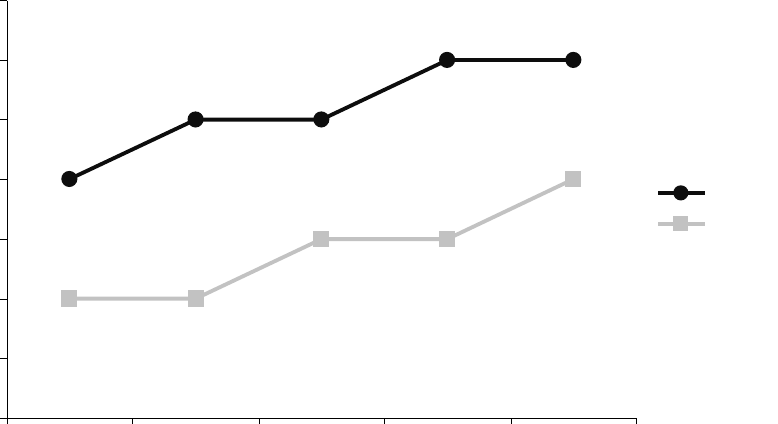

Figure 2: Families with Children by Family Type (1986-1996).................................................3

Figure 3: Family Type at Birth for Various Cohorts of Children ...............................................3

Figure 4: Marital Status of Male and Female Lone Parents (1991)............................................4

Figure 5: Proportion of Children in Private Households by Family Type (1996) ......................5

Figure 6: Poverty Rates by Family Type, 1996...........................................................................7

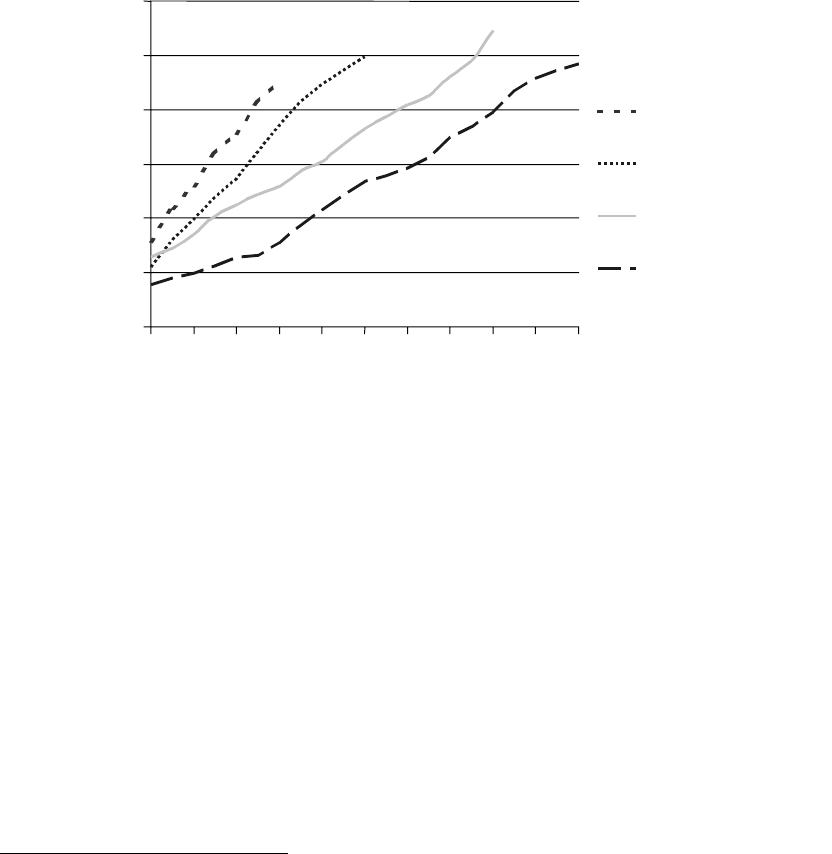

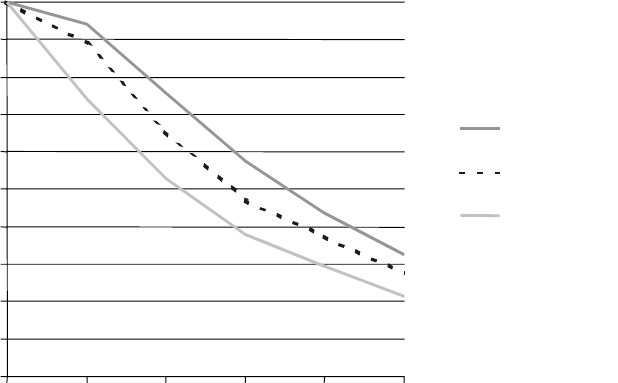

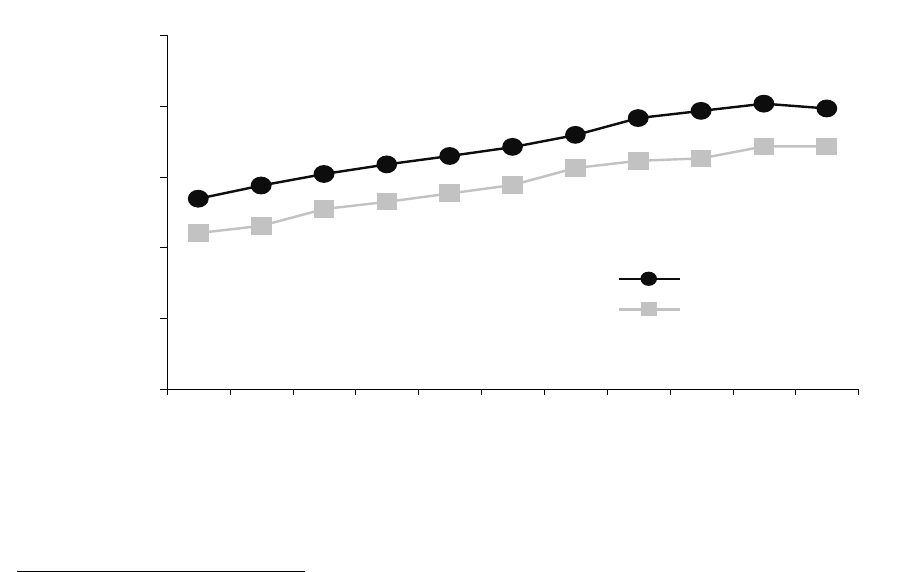

Figure 7: Marriage and Divorce Rates in Canada, 1967-1997....................................................9

Figure 8: Median Age at Time of Divorce, 1993-1997 ............................................................10

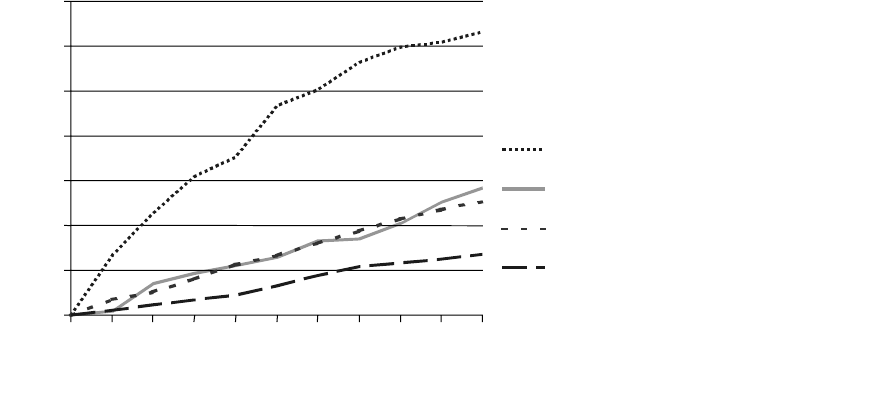

Figure 9: Canadian Children Born to a Lone-Parent or

Who Have Experienced the Separation of

Their Parents, Various Birth Cohorts........................................................................11

Figure 10: Canadian Children Born in a Two-Parent Family Who Have Experienced

Their Parents’ Separation, According to Type of Parents’ Union,

1983-1984 Cohorts—NLSCY 1994-1995.................................................................12

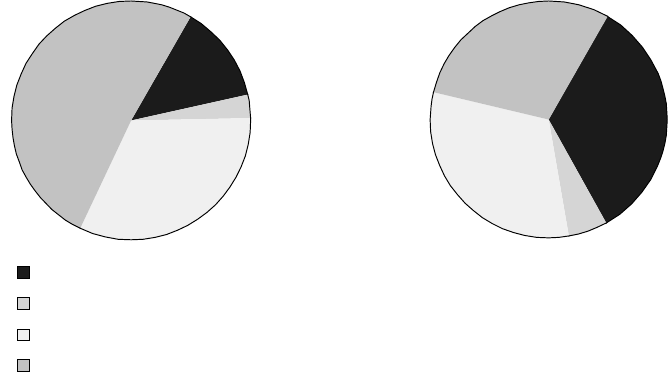

Figure 11: Distribution of Children Aged 0-11 and of Children

From Broken Families, According to Type of Parents’ Union—

Canada—NLSCY 1994-1995.................................................................................... 13

Figure 12: Percentage of Children From Broken Marriages Who Have Not Yet

Witnessed Their Parents’ Divorce, According to Time Elapsed

Since Separation—NLSCY 1994-1995 (Life Table Estimates)................................ 14

Figure 13: Type of Custody Arrangements.................................................................................17

Figure 14: Type of Contact Maintained with Either Parent at

Time of Separation NLSCY 1994-1995....................................................................18

Figure 15: Type of Contact Maintained with Father at the Time of Survey,

According to Time Elapsed Since Separation—NLSCY 1994-1995........................20

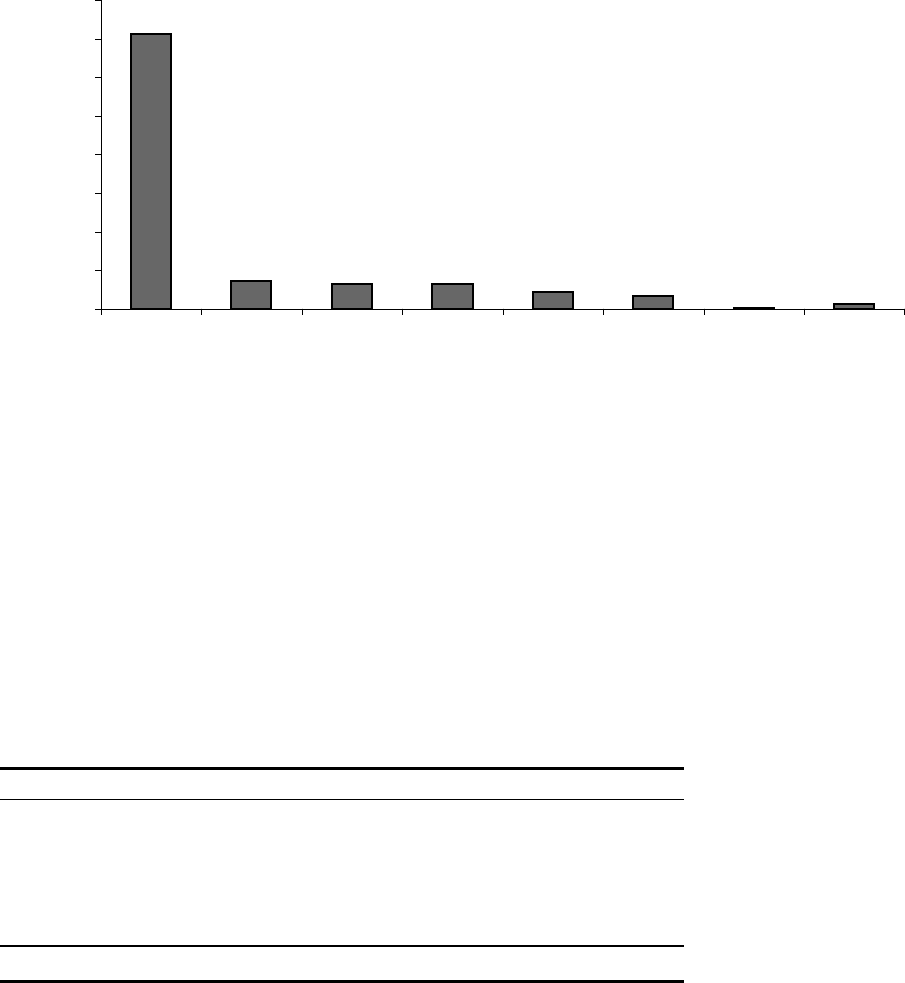

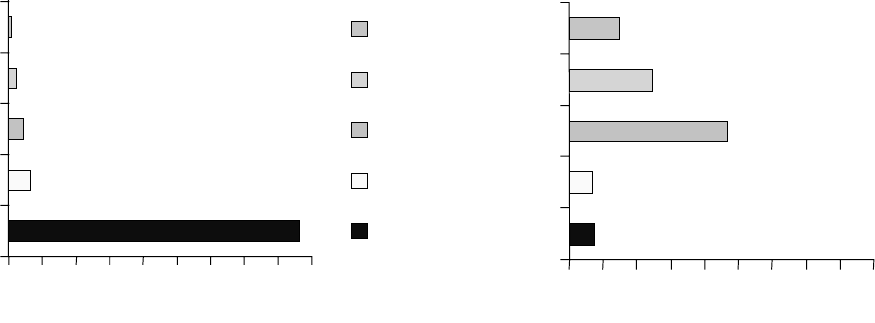

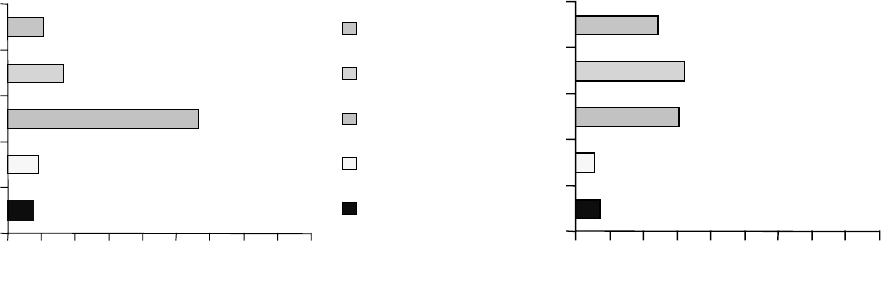

Figure 16: Number of People Who Reported Paying or

Receiving Support, 1986-1996..................................................................................21

Figure 17: Total Amount of Alimony by Number of

Payers and Recipients, Canada 1995.........................................................................22

- v -

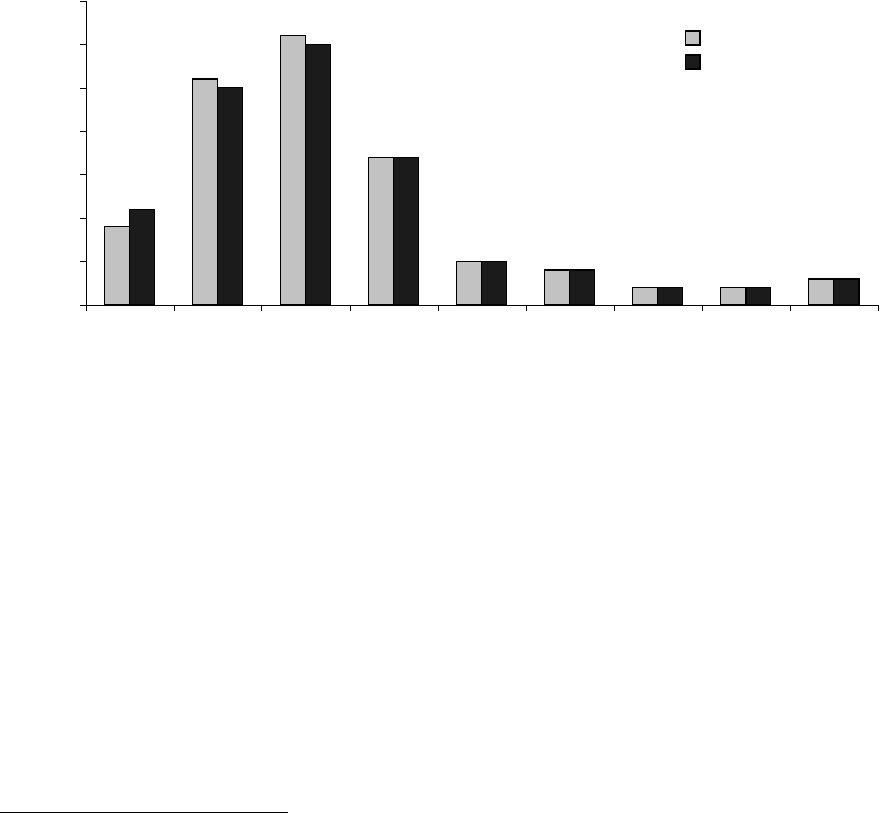

Figure 18: Income Ranges of Payers and Recipients, 1995........................................................ 23

Figure 19: Sources of Income, 1995...........................................................................................23

Figure 20: Government Transfers as a Source of Income,

for Payers and Recipients, Canada, 1995..................................................................24

Figure 21: Visiting Patterns with Father, for Children Living with

Mother at Time of Separation, According to Regularity of

Child Support Payments—NLSCY, Cycle 1, 1994-1995 .........................................27

- 1 -

INTRODUCTION

The following pages contain information on families in Canada, characteristics of those families

and information on family law topics such as marriage, divorce, support awards, payment of

child support, and custody and access. To produce the most accurate picture possible of the

circumstances of families in Canada, information and statistics from a number of different

sources have been compiled. At the heart of these sources are many Statistics Canada surveys

collecting data on various facets of Canadian life. Reports produced by other organizations,

generally using Statistics Canada data, have also been used. Therefore, when the term “family”

appears in the document it refers to the Statistics Canada definition of a census family: a

currently married or common-law couple with or without never-married children, or a single

parent with never-married children, living in the same dwelling.

Every attempt has been made to include the most recent information available. As relevant

information has been made public, this document has been updated. Certain information

contained in the previous publication of Selected Statistics has been repeated as it is based on

surveys, such as the census, that have not been repeated since the original publication appeared.

The other Statistics Canada surveys used in this report are the annual Survey of Labour and

Income Dynamics (SLID), and the divorce and marriage statistics.

There is an additional Statistics Canada survey that is of particular interest—the National

Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth (NLSCY), which began in 1994. This survey

collects, among other things, information on family law issues such as divorce, separation,

support payments, custody and access and a great deal of information from this survey has been

included in this report. A more detailed analysis of the family and custody history section of the

NLSCY (Cycle 1) can be found in the Department of Justice Canada publication entitled,

Custody, Access and Child Support: Findings from the National Longitudinal Survey of

Children and Youth (1999).

The appendix to this document briefly describes the various surveys used as sources in the

document. The bibliography provides details on the other sources from which information was

obtained.

- 2 -

FAMILY DEMOGRAPHICS

Family Type

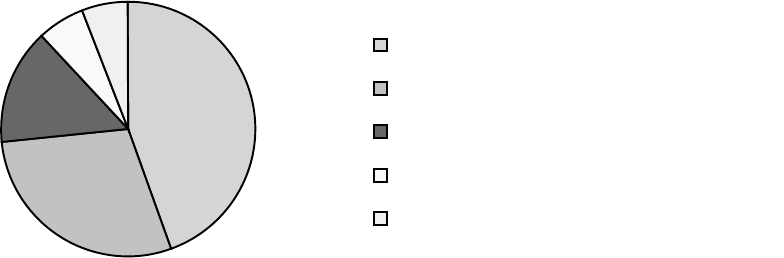

While the number of people living in families in Canada has been slowly declining, most people

(84 percent) still live in a family setting. In 1996, married couples with children represented

45 percent of all families; 29 percent were married couples without children; 15 percent were

lone-parent families; 6 percent were common-law couples with children; and 6 percent were

common-law couples without children.

Figure 1: Family Type as a Proportion of all Families (1996)

Source: Statistics Canada. “1996 Census: Marital Status, Common-Law Unions and Families” in The Daily.

Families with Children

The number of families with children, as a proportion of all families in Canada, has not changed

much over the past decade. In 1986, the number of families with children constituted 67 percent

of all families. In 1991 and 1996, the number of families with children was 66 percent.

Although the proportion of families with children has remained stable, the types of families with

children have changed. As indicated in Figure 2, the proportion of married-couple families with

children decreased steadily from 1986 (77 percent) to 1996 (69 percent). This decrease was

accompanied by increases in the numbers of both common-law families with children and lone-

parent families. Common-law families represented 4 percent of all families with children in

1986, and this figure rose to 8.5 percent in 1996. The number of lone-parent families increased

from 19 percent of all families with children in 1986 to 22 percent in 1996. Figure 2 illustrates

these trends.

29%

15%

6%

6%

45%

Married Couples With Children

Married Couples Without Children

Lone-Parent Families

Common-Law Couples With Children

Common-Law Couples Without Children

- 3 -

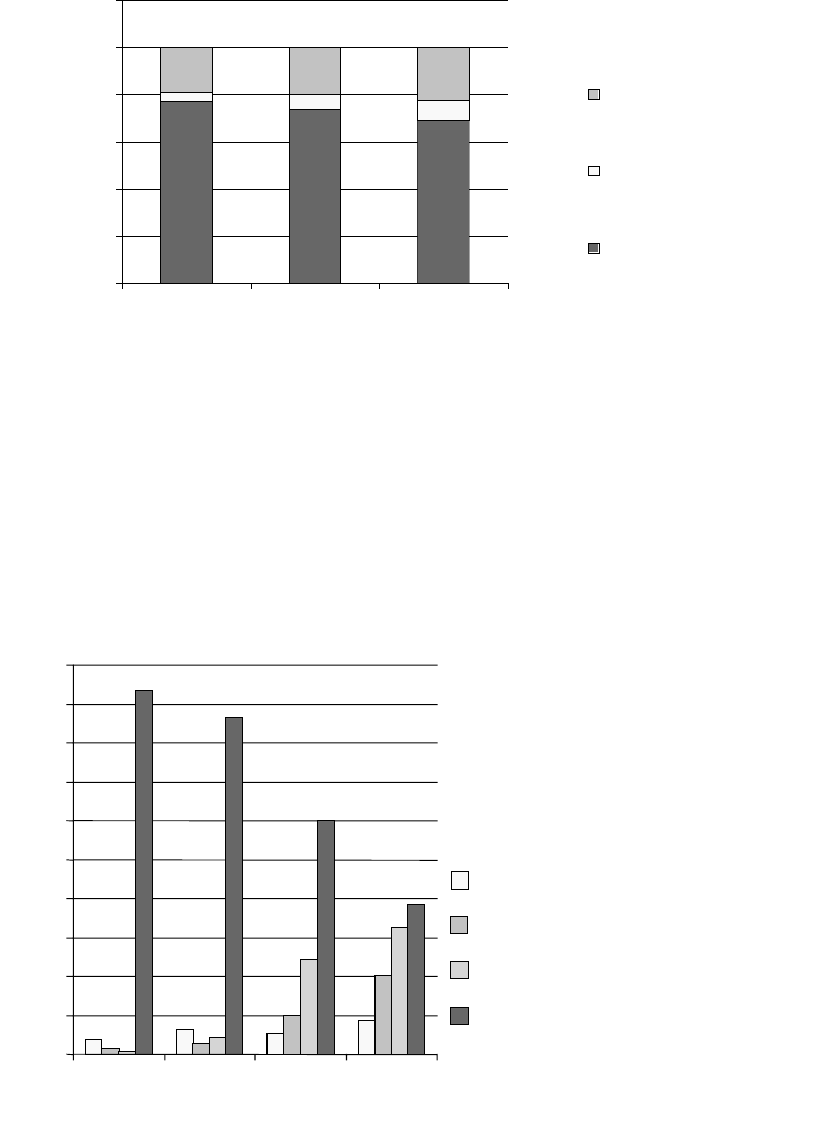

Figure 2: Families with Children by Family Type (1986-1996)

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

1986 1991 1996

(%)

Lone Parents

Common-Law Couples

Married Couples

Source: Statistics Canada. “1996 Census: Marital Status, Common-Law Unions and Families” in The Daily.

Family Context at Birth

Children are being born into very different types of families than they were thirty years ago. In

the sixties, most children were born to first-time married parents, that is, parents who had never

cohabited nor previously lived with another partner. Today, almost as many children are born

into two-parent families but, increasingly, their parents are not married.

Figure 3: Family Type at Birth for Various Cohorts of Children

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

1963 1973 1983 1993

Birth Cohorts

(

%)

Single Parent

Common-Law

Marriage, Common-Law Before

Marriage, No Common-Law Before

Source: Marcil-Gratton, N. & C. Le Bourdais (1999). Custody, Access and Child Support:

Findings from The National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth.

- 4 -

Figure 3 shows that nearly all children born in the early 1960s were born to parents who married

without living together before (over 90 percent). The situation has since changed radically. In

the National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth (NLSCY) 1993-1994 cohorts, children

born to parents who married without living together beforehand represented less than 40 percent

of all births. The biggest changes were in the proportion of children born to married parents who

first lived together (nearly 33 percent), and the proportion of children born to cohabiting parents

(20 percent). The changes were most marked in Quebec, where only 23 percent of the children in

the 1993-1994 cohorts were born to parents who married without prior cohabitation. Barely one-

half of all births were to married parents and 43 percent were to common-law couples. The

proportion of out-of-wedlock births reached 50 percent if one takes into consideration children

born to lone mothers.

Lone-Parent Families

Lone-parent families are much more likely to be headed by women than men. For example, in

1996 women headed 83 percent of all lone-parent families, while men headed only 17 percent of

lone-parent families. Although the number of lone-parent families has been increasing, the

proportion of female to male lone parents has remained relatively stable over the past decade.

The majority of female lone parents in 1991 were divorced (32.5 percent) or separated

(24.6 percent). Similarly, most male lone parents were divorced (33.6 percent) or separated

(37.6 percent). Men and women are less often lone parents due to the death of a spouse

(20.6 percent and 23.4 percent respectively) compared to the 1950s and 1960s, when almost two-

thirds of male and female lone parents were widowers or widows.

Figure 4: Marital Status of Male and Female Lone Parents (1991)

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

Single, never-married Separated Divorced Widowed

(%)

Male

Female

Source: Statistics Canada, by Colin Lindsay. Lone-Parent Families in Canada.

- 5 -

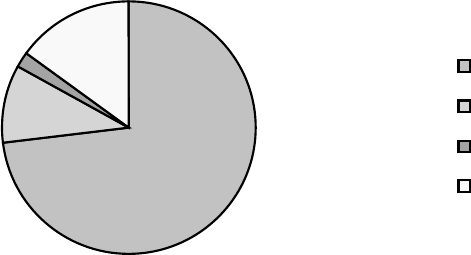

Although most children under the age of 17 belong to families in which the parents are married

(73 percent), a significant proportion of children belong to lone-parent families (17 percent).

Most of these children live in lone-parent families headed by women (15 percent) rather than

men (2 percent).

Figure 5: Proportion of Children in Private Households by Family Type (1996)

Source: Statistics Canada. “1996 Census: Marital Status, Common-Law Unions and Families” in The Daily.

While the proportion of children living with just one parent has remained constant at

approximately 17 percent over the past five years, the actual number of children living with a

lone parent increased from 1.5 million in 1991 to just under 1.8 million in 1996. This represents

an increase of 19 percent. Almost one in every five children in Canada lived with a lone parent

in 1996, and four out of five of these children (84 percent) lived with a female lone parent.

Family Income

The average family income in Canada increased slightly for some family types in the period

between 1993 and 1997, as shown in Table 1. For instance, in 1997 the average income of two-

parent families with children (one and two earners) increased by 3.3 percent from 1993. The

average family income for both male- and female-headed lone-parent families also increased by

4.8 percent over the same period. On the other hand, in lone-parent families where the mother is

not working, the average annual income decreased by 13.2 percent in the 5 year period. In 1997,

the average annual income of male lone-parent families ($38,101) was lower than two-parent

families with children where there is one earner ($46,308), and was even lower for female lone-

parent families where the mother is working ($27,923) or where the mother is on social

assistance ($12,883) (see Table 1 below).

73%

10%

2%

15%

Married Couple

Common-Law Couple

Male Lone Parent

Female Lone Parent

- 6 -

Table 1: Average Annual Income by Family Type, 1993-1997

1993

1994

1995

1

996

1997

Famil

y

T

yp

e

Constant 1997 Dollars

Census Families

1

54

,

803 55

,

730 55

,

877 56

,

162 56

,

628

Two-parent families with children

2

61,527 62,992 62,931 63,554 63,235

One earner 45,774 48,062 45,650 46,054 46,308

Two earners 63,722 65,791 65,844 66,375 66,299

Three or more earners 79,358 79,409 80,797 82,265 80,224

Other two-parent families

3

79,837 79,849 78,483 82,242 79,154

Lone-parent families

2

25,544 26,690 26,662 26,088 26,773

Male lone-parent families 36,073 36,514 36,658 38,501 38,101

Females lone-parent families 23,784 25,093 24,961 24,032 24,837

No earner 14,660 14,457 14,906 13,496 12,883

One earner 26,362 27,780 27,211 27,632 27,923

Other lone-parent families

3

44,622 43,371 42,673 44,080 44,937

1

A census family consists of either a husband and wife (with or without never-married children) or a parent

with one or more never-married children, living together in the same dwelling. Never-married children,

regardless of their age, living with their parent(s) are considered part of the family.

2

With single children less than 18 years of age. Children 18 years of age and over may also be present.

3

With single children 18 years of age and over only.

Source: Statistics Canada, Catalogue no. 13-208-XIB.

Family Poverty

Low income cutoffs (LICO) are frequently used to determine poverty levels, although Statistics

Canada warns that they “have no official status, and [Statistics Canada] does not promote their

use as poverty lines” (Poverty Profile 1996). LICOs represent levels of gross income where

people spend disproportionate amounts of money for food, shelter and clothing. Low-income

Canadians spend 20 percent more of their gross income on the necessities of life than the average

Canadian family.

The number of families with an income below the cutoffs in Canada was approximately

1,230,000 in 1996, or 14.8 percent of all families (Table 2). Most of these families (31 percent)

were single-parent mothers or couples under the age of 65 with children (30 percent). Of all the

other family types with an income below the cutoffs, 16 percent were childless couples under 65;

6 percent were couples 65 or older; and 17 percent were classified as other (these would include

families such as couples with children 18 or older, families headed by single fathers, and brothers

and sisters who live together).

- 7 -

Table 2: Families and Poverty (1996)

Poor Families

Family Type Number %

Single mothers 379,000 31

Couples under 65 with children 370,000 30

Other families 204,000 17

Childless couples under 65 199,000 16

Couples 65 or older 78,000 6

Total

1,230,000 100

Source: National Council of Welfare. Poverty Profile 1996.

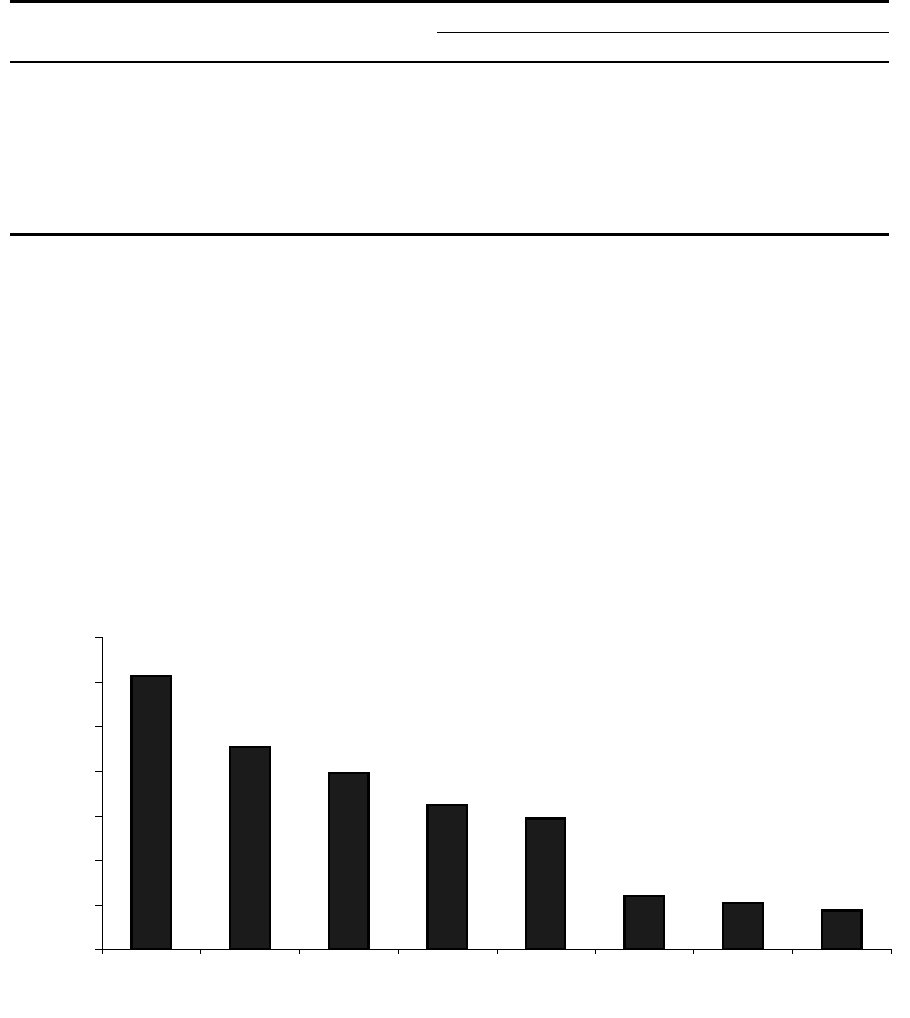

Poverty rates vary with family type, sex, age, employment, education, housing and the population

of the area in which people live. Family type is probably the most important factor in the risk of

poverty and the group with the highest poverty rate is single-parent mothers under the age of 65

with children under the age of 18. Over sixty percent of these families are poor (see Figure 6).

Moreover, the poverty rate for the relatively small number of families led by single mothers

under the age of 25 was incredibly high. In 1995, the rate was 83 percent, and in 1996 it was up

to 91.3 percent. The comparable rates for families led by single mothers aged 25 to 44 years old

was 61.2 percent, and 41.1 percent for single mothers aged 45 to 64 years old.

Figure 6: Poverty Rates by Family Type, 1996

Source: National Council of Welfare, Poverty Profile 1996, Spring 1998.

61.4

45.4

39.5

32.4

29.3

11.9

10.3

8.6

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

Single-Parent

Mothers <65

Unattached

Women 65+

Unattached

Women <65

Unattached

Men <65

Unattached

Men 65+

Couples <65

with Children

Childless

Couples <65

Couples 65+

(

%

)

- 8 -

MARRIAGE, DIVORCE AND SEPARATION

Marriage

The marriage rate for Canada in 1997 was 526 marriages per 100,000 people (see Table 3).

Marriage rates for most provinces did not vary greatly from the national rate. However, the

Northwest Territories (311) and Quebec (322) showed the lowest rates for that year. In contrast,

Prince Edward Island (699) and the Yukon (759) had the highest marriage rates in 1997.

Table 3: Number and Rate of Marriages and Divorces,

Canada and Provinces/Territories, 1997

Marriages Divorces

Number Rate Number Rate

per 100,000 per 100,000

Canada 159,350 526 67,408 223

Newfoundland 3,235 574 822 146

Prince Edward Island 960 699 243 177

Nova Scotia 5,525 583 1,983 209

New Brunswick 4,340 570 1,373 180

Quebec 23,875 322 17,478 236

Ontario 67,540 592 23,629 207

Manitoba 6,620 578 2,625 229

Saskatchewan 5,700 557 2,198 215

Alberta 17,860 627 7,185 252

British Columbia 23,245 591 9,692 246

The Yukon 240 759 101 319

Northwest Territories 210 311 79 117

Source: Statistics Canada. Marriages 1997, and Divorces 1996-1997.

The marriage rate in Canada was similar to the rate observed in the United Kingdom (523 per

100,000) and Australia (570 per 100,000). The marriage rate in the United States was 1.5 times

higher than in Canada in 1997 (890 per 100,000).

Divorce

In 1997, the overall divorce rate for Canada declined for the fifth consecutive year. There were

223 divorces per 100,000 people, or 67,408 divorces granted in 1997 (see Table 3). The lowest

divorce rates were in the Northwest Territories (117) and Newfoundland (146), while the highest

rates were in the Yukon (319) and Alberta (252). The rate was generally lower in the Atlantic

provinces (Newfoundland, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick) and higher

in three of the four most populous provinces of the country (Quebec, Alberta and British

Columbia).

Canada’s divorce rate was lower than in most industrialized nations. For example, the United

Kingdom and Australia have a slightly higher divorce rate than in Canada (273 and 280 per

- 9 -

100,000 respectively) and the American divorce rate was almost double the Canadian rate

(430 divorces per 100,000) in 1997.

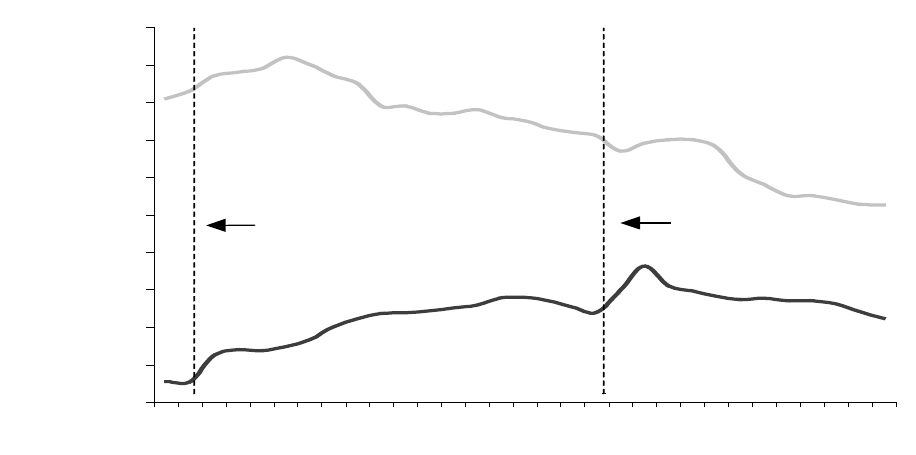

Trends in Marriage and Divorce

Figure 7 illustrates the trends in marriage and divorce in Canada over the last 30 years. Marriage

rates reached their peak in the early 1970s (920 marriages per 100,000 people in 1972) and have

slowly declined since. There was, however, a slight increase in the rate between 1986 and 1989,

which may represent the backlog of people who were able to marry again after their divorce was

finalized following the 1985 amendments to the Divorce Act. Since the early 1990s, marriage

rates have been decreasing.

Figure 7: Marriage and Divorce Rates in Canada, 1967-1997

Source: Statistics Canada. Divorces (1987-1988, 1990, 1991, 1992, 1993, 1994, 1995, 1996-1997).

Between 1982 and 1985, the divorce rate declined, most likely in anticipation of the 1985

amendments to the Divorce Act. With the amendments, it became easier to obtain a divorce.

The necessity to prove fault was reduced, and marriage breakdown (separation for at least one

year) became the most frequently cited ground for divorce. In the two years following the

implementation of the amendments, the divorce rate rose significantly; it reached its peak in 1987

at 362 divorces per 100,000 people. Since then, the divorce rate in Canada has fallen and in

1997 it was 223 divorces per 100,000 people.

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

700

800

900

1,000

1967 1977 1987 1997

Rate per 100,000 population

Marriage

Divorce

Divorce Act 1968

Divorce Act 1985

amendments

- 10 -

Duration of Marriage and Age at Time of Divorce

In 1997, the median duration of marriages in Canada was 11 years at the time of divorce,

compared to 10 years in 1995. There were variations at the provincial level. For example, the

median duration of marriage reached a high of 13 years in both Newfoundland and Quebec and a

low of 8 years in the Northwest Territories.

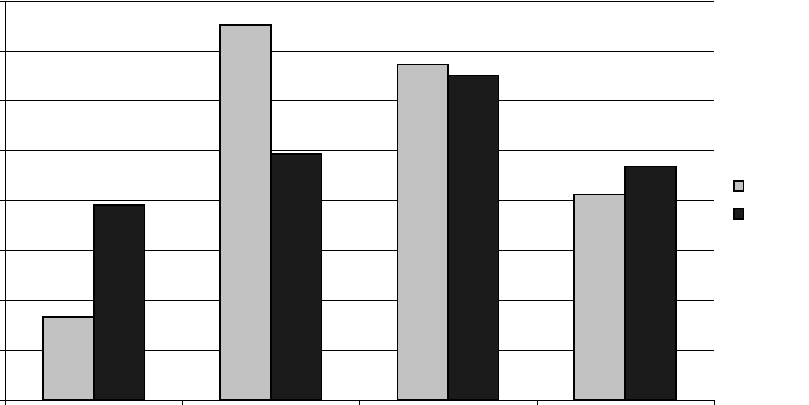

Figure 8 shows that age at the time of divorce has been rising for both men and women since

1993, and that women are generally younger when they divorce than men. The median age at the

time of divorce varied by province. It was slightly higher than the national median age in Quebec

and the Yukon, and lower in the Northwest Territories.

Figure 8: Median Age at Time of Divorce, 1993-1997

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

1993 1994 1995 1996 1997

Median Age

Male

Female

Source: Statistics Canada. Divorces (1993, 1994, 1995, 1996-1997).

- 11 -

CHILDREN AND SEPARATION AND DIVORCE

1

The Complex Family Lives of Canadian Children

Recent demographic data show that an increasing proportion of children are living in single-

parent families and at an increasingly young age. Figure 9 presents the proportion of Canadian

children who experienced life in a single-parent family among various birth cohorts.

Specifically, it shows the cumulative percentage of children who were born to a lone parent or

who had experienced their parents’ separation before their last birthday.

Figure 9: Canadian Children Born to a Lone-Parent or Who Have Experienced

the Separation of Their Parents, Various Birth Cohorts

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

0 2 4 6 8 101214161820

Age of Child

(%)

1987-1988 Cohorts

1983-1984 Cohorts

1971-1973 Cohorts

1961-1963 Cohorts

Source: Marcil-Gratton, N. & C. Le Bourdais (1999). Custody, Access and Child Support:

Findings from The National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth.

Thirty years ago, almost 25 percent of children were either born to a single mother or had

experienced their parents’ separation before the age of 20. Half of the parents of this group had

separated after the child reached the age of 10.

Children who were born 10 years later (1971-1973 cohorts) experienced their parents’ separation

at an even younger age. By age fifteen, 25 percent of these children had already experienced life

in a single-parent family. Three times out of four, the child had experienced this before the age

of ten.

Children who were born after 1983 experienced their parents’ separation even earlier. By age 10,

one child out of four born in 1983-1984 had experienced life in a single-parent family and nearly

1

The information in the next three sections is taken from Marcil-Gratton, Nicole and Céline Le Bourdais,

Custody, Access and Child Support: Findings from the National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth. (1999).

- 12 -

23 percent of children in the younger cohorts (those born in 1987-1988) experienced the same by

the age of 6.

There is little reason to suggest that these trends will slow down in the near future, since the

rising proportion of children born in common-law unions face a higher risk of experiencing their

parents’ separation.

Children from Broken Families Come Disproportionately from Common-Law Unions

The parents’ decision to live together rather than marry has far-reaching consequences for the

survival of the family unit. Figure 10 presents the cumulative percentage of Canadian children,

born in two-parent families, who experienced parental separation according to the type of

parental union.

In the 1983-1984 cohorts, 60 percent of the children were born to parents who married without

first cohabiting, and 24 percent were born to parents who married after cohabiting. Another

10 percent of children were born to cohabiting parents and for 3 percent of this group, their

parents married before the child’s tenth birthday. Children born to a single parent (6 percent) are

not counted here.

Figure 10: Canadian Children Born in a Two-Parent Family Who Have Experienced

Their Parents’ Separation, According to Type of Parents’ Union,

1983-1984 Cohorts—NLSCY 1994-1995

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

012345678910

Age of Child

(%)

Common-Law

Common-Law, Married Since

Marriage, Common-Law Before

Marriage, No Common-Law Before

Source: Marcil-Gratton, N. & C. Le Bourdais (1999). Custody, Access and Child Support:

Findings from The National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth.

- 13 -

As we have seen, increasing numbers of children from broken homes were born to parents who

did not marry. Figure 11 below presents the information somewhat differently by illustrating the

distributions of children from birth to 11 years old and of children from broken families

according to the type of parental union.

According to the NLSCY, the majority of children (fifty-two percent) were born to couples who

had not lived together before marriage and another thirty-two percent were born to married

parents who had first lived together. Thirteen percent were born into a common-law union that

had not been formalized into a marriage at the time of the survey (See Figure 11).

Figure 11: Distribution of Children Aged 0-11 and of Children

From Broken Families, According to Type of

Parents’ Union—Canada—NLSCY 1994-1995

13%

3%

52%

32%

Common-Law

Common-Law, Married

S

Marriage, Common-Law Before

Marriage, No Common-Law Before

30%

31%

5%

34%

Children from Broken Families

All Children

Source: Marcil-Gratton, N. & C. Le Bourdais (1999). Custody, Access and Child Support:

Findings from The National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth.

For children whose parents had separated, only 30 percent came from married couples who had

not lived together before marriage. A slightly greater proportion (34 percent) were from

common-law couples who had not married at the time of the survey. Children born to common-

law unions were clearly over-represented among children who experienced the break-up of their

families.

Patterns of Separation and Divorce

Are changes in the way people enter into unions accompanied by changes in the way they end

them? Are the legally married couples who are separating in greater and greater numbers doing

so without ever legalizing the break-up through divorce?

The survival curves presented in Figure 12 provide data to answer these questions. These curves

show, for given regions, the percentage of children from broken marriages whose parents had not

- 14 -

divorced, according to the time elapsed since separation. Obviously, the results presented in

Figure 12 are linked to the grounds under which one can obtain a divorce and regional

differences in the divorce process itself, which can affect the time it takes to get a divorce.

Figure 12: Percentage of Children From Broken Marriages Who Have Not Yet

Witnessed Their Parents’ Divorce, According to Time Elapsed Since

Separation—NLSCY 1994-1995 (Life Table Estimates)

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

012345

Years Since Separation

(%

)

Ontario

Canada

Quebec

After 5 Years:

Atlantic Provinces = 29.6

Prairies = 24.9

British Columbia = 25.3

Source: Marcil-Gratton, N. & C. Le Bourdais (1999). Custody, Access and Child Support:

Findings from The National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth.

As Figure 12 shows, in Canada almost half (47 percent) of the children from broken marriages

had not seen their parents divorce after three years of separation and this percentage was still

28 percent after five years of separation. One may well ask whether the couples who have not

divorced after five years will ever obtain a divorce.

Apart from Quebec, the proportion of children in different regions of the country whose parents

had not yet divorced after five years did not vary greatly from the national average. Figure 12

shows that in Quebec, only 74 percent (as compared to 94 percent in Ontario) of children from

broken marriages had not seen their parents divorce after one year and this percentage drops to

21 percent after five years.

- 15 -

CHILD CUSTODY

Custody Arrangements

More and more couples are living together and having children without marrying. Often, family

break-ups occur without any recourse to the legal system. Does this affect the likelihood of

separated parents obtaining a court order for custody? Is the issue of custody increasingly settled

out of court? The NLSCY provides a wealth of information on the arrangements parents make

for the care of their children when they separate.

Existence of Court Orders for Custody and Variations by

Time Since Separation and Type of Separation

Table 4 provides a breakdown of the frequency with which court orders were obtained for the

custody of the children. In Canada as a whole, parents reported they had a court order, or that

they were in the process of obtaining one, in 48 percent of the cases.

Table 4: Distribution of Children According to Whether a Court Order for Custody

Exists, by Type of Broken Union and Time Elapsed Since Separation—

NLSCY, Cycle 1, 1994-1995

Court

Order

Court Order

in Progress

Not Submitted

to the Court Total N

1

Canada 37.4 10.1 52.5 100 3295

Type of broken union

Common-law 27.9 11.9 60.2 100 1175

Marriage, common-law before 42.4 9.4 48.2 100 1141

Marriage, no common-law before 44.1 7.8 48.2 100 927

Time elapsed since separation

Less than 1 year 15.7 11.3 73.0 100 566

1-2 years 29.3 10.4 60.3 100 906

3-4 years 43.2 12.6 44.2 100 761

5 years and over 51.7 7.3 41.0 100 1062

1

N = Weighted data brought back to the original sample size.

Source: Marcil-Gratton, N. & C. Le Bourdais (1999). Custody, Access and Child Support:

Findings from The National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth.

As would be expected, the lower portion of Table 4 shows that the number of cases in which

parents said they had a court order rises as the time elapsed since separation increases. In the

first year after separation, a court order for custody exists in only one case out of four, and after

five years, the percentage has risen to 59 percent.

Custody

Table 5 shows who received custody of the children and the type of contact that was maintained

with the non-custodial parent in cases where the parents said they had a court order.

- 16 -

Table 5: Court-Ordered Custody Arrangement, According to

the Age of the Child at Separation and the

Type of Broken Union—NLSCY, Cycle 1, 1994-1995

Mother

Exclusive

Custody

Father

Exclusive

Custody

Shared

Physical

Custody Other Total N

1

(%)

Canada

79.3 6.6 12.8 1.2 100 1239

Age of child at separation

0-5 years 80.6 6.0 12.4 1.1 100 1046

6-11 years 74.0 8.1 15.7 2.1 100 187

Type of broken union

Common-law 84.1 6.2 8.7 1.0 100 328

Marriage, common-law before 74.3 7.9 16.8 0.9 100 489

Marriage, no common-law before 82.0 5.3 10.9 1.8 100 409

1

N = Weighted data brought back to the original sample size.

Source: Marcil-Gratton, N. & C. Le Bourdais (1999). Custody, Access and Child Support:

Findings from The National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth.

The results of Table 5 confirm what is known based on other data sources: after separation,

mothers were given custody of the children in the overwhelming proportion of cases. Close to

80 percent of children under the age of 12 were placed in their mothers’ custody in cases where a

court order existed. Almost 7 percent were placed in their fathers’ custody, and for 13 percent of

children, a shared custody arrangement was established.

These proportions change according to the age of the children at the time of separation. Older

children are more likely to be placed in their fathers’ care or in joint custody arrangements.

Among children aged 6 to 11, one child in four was entrusted to the fathers’ care, either

exclusively (8 percent) or jointly with the mother (16 percent). Among children aged 6 and

under, only 18 percent were in the sole custody of their fathers or in joint custody. Finally,

children from broken common-law unions (84 percent), as well as children from Quebec

(87 percent), were most likely to remain in the custody of their mothers, and there is possibly a

link between these two results.

The Department of Justice’s survey of child support awards also collected information on the

custody of the children. Figure 13 shows the results of the custody portion in this survey. The

overall patterns are similar to those found in the NLSCY.

- 17 -

Figure 13: Type of Custody Arrangements

71.2

7.2

6.4

6.3

4.2

3.2

0.1

1.3

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

Sole

Custody

Mother

Sole

Custody

Father

Shared

Custody

No Order Split

Custody

Unable to

Determine

Split and

Shared

Custody

Other

(%)

N = 5,818

Source: Hornick, J.P, Lorne Bertrand and Nicholas Bala. The Survey of Child Support Awards: Preliminary

Analysis of Phase 2 Data, Department of Justice, Child Support Team, 1999.

Living Arrangements

Regardless of the custody arrangements that parents reported, the data in Table 6 show that

87 percent of the NLSCY children lived solely with their mothers at the time of their parents’

separation.

Table 6: Living Arrangements at Time of Separation for

Children of Broken Families—NLSCY,

Cycle 1, 1994-1995

Living Arrangement %

Child lives with mother only 86.8

Child lives with father only 7.0

Shared, mainly mother 2.9 N

1

= 3,276

Shared, mainly father 0.9

Equally shared 2.5

Total

100.0

1

N = Weighted data brought back to the original sample size.

Source: Marcil-Gratton, N. & C. Le Bourdais (1999). Custody, Access and Child Support:

Findings from The National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth.

Contact with Non-custodial Parent

For the first time, the NLSCY collected national data on the amount of contact between non-

custodial parents and their children. The survey did not address the reasons for the patterns of

contact, but it did provide information on those patterns and the factors associated with them.

- 18 -

Figure 14 shows the distribution of children from broken families according to the type of

contact maintained with either parent at the time of separation, regardless of whether the broken

union was common-law or marriage.

Figure 14: Type of Contact Maintained with Either Parent at

Time of Separation NLSCY 1994-1995

7%

7%

47%

25%

15%

0

%

10

%

20

%

30

%

40

%

50

%

60

%

70

%

80

%

90

%

100%

200%

300%

400%

500%

7%

86%

4%

1%

2%

0

%

10

%

20

%

30

%

40

%

50

%

60

%

70

%

80

%

90

%

Never Visits

Visits Irregularly

Visits Regularly

Shares Residence

Lives With ...

Father

Mother

Source: Marcil-Gratton, N. & C. Le Bourdais (1999). Custody, Access and Child Support:

Findings from The National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth.

Very few children (7 percent) lived with their fathers only and another small fraction shared

residence with both parents (7 percent). The rest of the children (86 percent) lived with their

mothers and visited their fathers with varied frequency. Close to half of the children visited their

fathers on a regular basis; less than a third (30 percent) visited every week; and another

sixteen percent visited every two weeks (see Table 7). One-quarter of the children visited their

fathers irregularly (once a month, on holidays, or at random). Fifteen percent of children never

saw their fathers (although a small number had letter or phone contact with him).

Table 7 illustrates the differences in the amount of contact non-custodial parents maintained with

their children according to the type of parental union at the time of separation. Firstly, children

from common-law unions were more likely to live with their mothers at the time of separation

than children whose parents were married (91 percent versus 83 percent). Secondly, they were

less likely to live in a shared custody arrangement (3 percent versus 8 percent). Finally, twice the

number of children from broken common-law unions never saw their fathers, compared to

children whose parents had been married (21 percent versus 11 percent).

Children whose parents were married before the separation were slightly more likely to live with

their fathers after the separation than children from common-law unions (8 percent versus

5 percent). In addition, even though they were less likely to live with their mothers after

separation, they were more likely than children from common-law unions to see their fathers

once a week (32 percent versus 28 percent).

- 19 -

Table 7: Type of Contact Maintained With Either Parent at Time of Separation by

Type of Union—NLSCY, Cycle 1, 1994-1995

Canada

Marriage Common-Law Total

Type of Contact

(%)

Child lives with mother only:

83.2 91.4 86.2

Never visits father * 11.1 21.3 14.8

Visits father irregularly * 25.3 23.3 24.6

Visits father every two weeks 14.9 19.1 16.4

Visits father once a week 31.9 27.7 30.4

Child lives with father only:

8.4 5.3 7.3

Never visits mother * 0.3 1.2 0.7

Visits mother irregularly * 2.5 1.8 2.2

Visits mother every two weeks 2.3 1.2 1.9

Visits mother once a week 3.3 1.1 2.5

Child shares residence with

both parents

8.4 3.2 6.5

Total

100.0 100.0 100.0

N

1

2028 1158 3187

* “Irregular” visiting includes once a month, on holidays only and at random; “never” includes contact by

telephone or letter only.

1

N = Weighted data brought back to the original sample size.

Source: Marcil-Gratton, N. & C. Le Bourdais (1999). Custody, Access and Child Support:

Findings from The National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth.

Contact with Non-custodial Parent over Time

The NLSCY data show how the frequency of contact between fathers and their children is related

to the time since the separation of the parents. Also, the likelihood of children living with both

parents after the separation, or visiting regularly with their fathers, decreases over time.

As Figure 15 shows, children whose parents were separated less than two years shared residences

with both parents in nine percent of cases compared to only six percent of children whose parents

were separated for at least five years. The regularity of visits also drops considerably over time.

Fifty-seven percent of children whose parents had been separated for less than two years at the

time of the survey visited their fathers regularly (every week or every two weeks). This

percentage drops to thirty-one percent when the parents had been separated five or more years

before the survey. Moreover, close to a quarter of children whose parents had been separated at

least five years never saw their fathers.

- 20 -

Figure 15: Type of Contact Maintained with Father at the Time of Survey, According to

Time Elapsed Since Separation—NLSCY 1994-1995

7%

6%

31%

32%

24%

0

%

10

%

20

%

30

%

40

%

50

%

60

%

70

%

80

%

90

%

100%

200%

300%

400%

500%

9%

8%

57%

10%

16%

0

%

10

%

20

%

30

%

40

%

50

%

60

%

70

%

80

%

90

%

Never Visits

Visits Irregularly

Visits Regularly

Shares Residence

Lives With Father

5 years or more

Less than 2 years

Source: Marcil-Gratton, N. & C. Le Bourdais (1999). Custody, Access and Child Support:

Findings from The National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth.

- 21 -

CHILD AND SPOUSAL SUPPORT PAYMENTS

Information on child and spousal support payments is available from a variety of sources. Six

sources are considered here. Revenue Canada publishes yearly tax statistics which provide the

number of persons paying and receiving alimony,

2

the amounts paid, the amounts claimed as

income, and the sources of income of payers and recipients. Statistics Canada’s Survey of

Labour and Income Dynamics is a longitudinal survey of households in which respondents

provide details on their sources of income, and support payments appears as a separate data

element here. There were also several questions on child support in the NLSCY. Finally, the

Department of Justice’s survey of child support awards collects data on child support orders in

11 courts across the country to monitor the implementation of the Federal Child Support

Guidelines.

Number of People Paying and Receiving Support between 1986 and 1996

Revenue Canada data indicate that since 1986, the number of people paying and receiving

support has been increasing steadily. Figure 15 shows that the number of people receiving

support has increased 55.6 percent between 1986 and 1996. The number of people paying

support has increased 47.6 percent in the same period. A slight decline (less than 2 percent) in

the number of people who reported paying support was observed between taxation years 1995

and 1996 (403,160 and 396,100 respectively).

Figure 16: Number of People Who Reported Paying or

Receiving Support, 1986-1996

Source: Revenue Canada. Taxation Statistics, 1986-1996.

2

In Revenue Canada reports, the term “alimony” includes both child support and spousal support amounts.

396,100

329,389

268,292

342,900

220,302

276,157

0

100,000

200,000

300,000

400,000

500,000

1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996

Number Reported

Paid

Received

- 22 -

Figure 17 provides the distribution of the amount of alimony declared on income tax forms by

payers and recipients in 1995. Payers reported paying an average amount of $5,274 in

alimony/child support while recipients reported receiving an average of $5,378 for that year.

Fifty-six percent of payers and fifty-five percent of recipients declare either paying or receiving

less than $4,000 per year in alimony/child support. Two-thirds of payers and recipients declare

paying or receiving less than $5,000 per year. The most commonly reported amounts are

between $2,000 and $2,499 per year, and between $4,000 and $4,999 per year, which is about

$200 and $400 per month, respectively. These amounts presumably correspond to what payers

and recipients reported for one child and for two children. The distribution is virtually identical

for payers and recipients.

Figure 17: Total Amount of Alimony by Number of Payers and

Recipients, Canada 1995

Source: Revenue Canada, Taxation Statistics, 1995.

Income Levels of Payers and Recipients of Child Support

3

Figure 18 shows the difference in the income ranges of payers and recipients, according to

Revenue Canada data for taxation year 1995. Almost two-thirds of recipients reported a total

income of less than $20,000 per year, compared to 26 percent of payers. In contrast, close to

one-half (46 percent) of payers reported an income over $30,000 per year, compared to

15 percent of recipients.

3

Revenue Canada defines income as the amount reported on line 150 of the income tax return or the total of

items 4 to 22.

9

26

31

17

5

4

22

3

11

25

30

17

5

4

22

3

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

Less than

1,000

1,000-

2,499

2,500-

4,999

5,000-

7,999

8,000-

9,999

10,000-

12,499

12,500-

14,999

15,000-

19,999

20,000+

Alimony Amount ($)

(

%

)

Payers

Recipients

- 23 -

Figure 18: Income Ranges of Payers and Recipients, 1995

Source: Revenue Canada, Taxation Statistics, 1995.

Sources of Income

There are significant differences in the sources of income for both payers and recipients for 1995.

The majority of recipients reported wages and salaries (72 percent) as a source of income,

followed by government transfers (for example, social assistance, employment, insurance and old

age security) at 55 percent. In contrast, payers reported wages and salaries (96 percent) in a

much higher proportion of their income while 37 percent reported government transfers as one

other source of income.

Figure 19: Sources of Income, 1995

1

1

Totals do not add to 100 percent due to multiple responses.

Source: Revenue Canada, Taxation Statistics, 1995.

4

22

28

27

7

12

16

46

23

12

2

1

0

10

20

30

40

50

Less than

10,000

10,000-

19,999

20,000-

29,999

30,000-

39,999

40,000-

49,999

50,000 +

Income Range ($)

(%)

Payers

Recipients

96

37

47

16

20

72

55

37

9

14

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

Wages and

Salaries

Government

Transfers

Investment

Income

Self-

Employment

Income

Other Income

Source of Income

(%)

Payers

Recipients

- 24 -

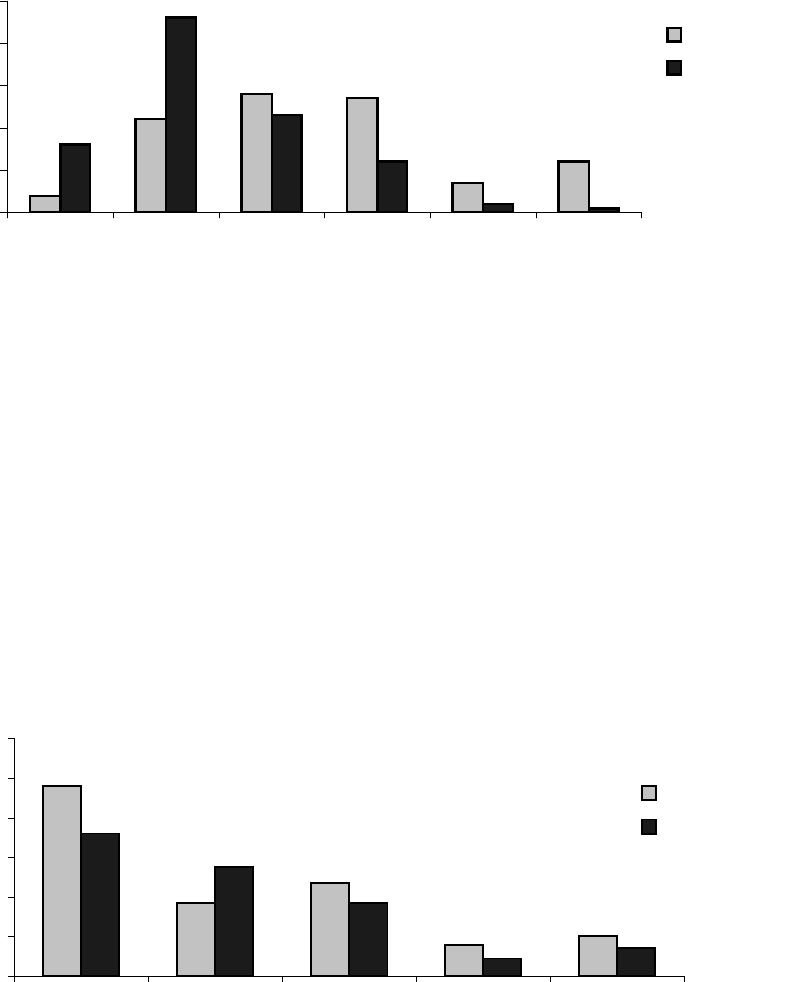

Where payers and recipients claimed government transfers as a source of income, figure 20

shows the type of government program that provided the income. More than one-quarter

(28 percent) of recipients reported social assistance as a source of income, compared to only

4 percent of payers. There were no significant differences in the proportion of payers and

recipients claiming employment insurance as a source of income, nor were there significant

differences reported for the other types of government transfers.

Figure 20: Government Transfers as a Source of Income,

for Payers and Recipients, Canada, 1995

Source: Revenue Canada, Taxation Statistics, 1995.

Statistics Canada’s Survey of Labour and Income Dynamics (SLID) is another source of

information on family income and sources of income.

4

Among other things, it provides national

data on single mother families receiving social assistance and support payments as a source of

income. According to this survey, 20 percent of social assistance recipients were single parents

(male and female) in 1994. Single mothers accounted for over 90 percent of custodial parents

receiving social assistance and almost one-half (48 percent) of female single parents received

social assistance. Nationally, 72 percent of single mothers with a child under five years old

received social assistance and two-thirds of single mothers receiving social assistance had at least

one child under ten.

The SLID also provides data on alimony as a source of income. In 1994, female single parents

(with all children under the age of 25) accounted for about one-half of all alimony recipients.

Another 28 percent of alimony recipients (almost all women) were married or in a common-law

4

The information in the following paragraphs is from Kerr, R. Social Assistance and Child Support: A Pilot

Survey (1999).

19

6

4

3

6

16

2

28

3

5

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

Employment

Insurance

Other pensions Social Assistance Old Age Security Canada/Quebec

Pension Plan

(%)

Payers

Recipients

- 25 -

relationship and had children under the age of 25. Approximately one-third of alimony recipients

also received social assistance. Of these, at least 75 percent were single mothers.

Almost half (47 percent) of single mothers who received alimony also received social assistance

for at least part of the year. Only one-quarter of all single mothers received alimony and this

proportion does not appear to be much different for single mothers who received social

assistance. The proportion of single mothers who received alimony increases to about 31 percent

if only “separated and divorced” single mothers are considered (that is, excluding the “single

never-married” and “widowed” mothers).

Interestingly, single mothers with two or more children are somewhat more likely to receive

alimony and in larger amounts than mothers with only one child. The likelihood of single

mothers receiving alimony does not appear to vary significantly by the mothers’ levels of

education, except that mothers with a post-secondary degree or certificate receive higher

amounts.

Child Support Arrangements

The NLSCY provides information on the child support arrangements parents made when they

separated.

Table 8 shows the distribution of Canadian children from broken homes by type of support

agreement, according to the type of separation.

Table 8: Type of Support Agreement According to Type

of Broken Union—NLSCY, Cycle 1, 1994-1995

Type of Broken Union (%)

Type of Support

Agreement

Marriage

Divorce

Marriage

Separation

Common-Law

Separation

All

Unions

Court order 48.7 15.6 20.3 27.8

Court order in progress 8.3 8.3 8.2 8.3

Private agreement 25.9 39.4 29.2 31.5

No agreement 17.2 36.7 42.2 32.5

Total 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0

N

1

1047 1077 1184 3308

1

N = Weighted data brought back to the original sample size.

Source: Marcil-Gratton, N. & C. Le Bourdais (1999). Custody, Access and Child Support:

Findings from The National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth.

The most significant finding is that for almost one-third of Canadian children whose parents have

separated, the parents said there was no agreement regarding child support payments.

Children whose parents had divorced at the time of the survey were more likely to be covered by

some type of child support agreement than children whose parents had not divorced. When the

parents were divorced, parents said there was a court order in place, or in progress, in 57 percent

of cases and there was no agreement in only 17 percent of cases.

- 26 -

Forty-two percent of children from broken common-law unions were not covered by any form of

child support agreement. They were followed closely by children whose parents had not yet

divorced at the time of the survey (thirty-seven percent).

Regularity of Payments

Table 9 shows that, in general, more children who are covered by what their parents describe as a

private agreement receive regular support payments than children whose parents say they have a

court-ordered agreement. Two-thirds of children under private agreements benefited from

regular support payments, compared to 43 percent of children whose parents stated they had a

court-ordered agreement. Moreover, cases where there have been no payments in the last six

months are much more common where the parents said there was a court order than where

support payments are dealt with through a private agreement (30 percent vs. 14 percent).

Table 9: Type of Support Agreement and Regularity of Payments, According to Type

of Broken Union—NLSCY, Cycle 1, 1994-1995

Type of Support Agreement and Regularity of Payments (%)

Court-ordered Private

Type of

Broken

Union Regular Irregular

None for

at Least

6 Months Total N

1

Regular Irregular

None for

at Least

6 Months Total N

1

Marriage 43.9 31.3 24.8 100 665 72.9 18.7 8.4 100 595

Common-law 41.0 14.2 44.8 100 232 53.4 22.3 24.3 100 309

All 43.0 27.0 30.0 100 897 66.3 19.9 13.8 100 904

1

N = Weighted data brought back to the original sample size.

Source: Marcil-Gratton, N. & C. Le Bourdais (1999). Custody, Access and Child Support:

Findings from The National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth.

This trend holds true regardless of the type of broken union. For children whose parents were

married and made a private agreement regarding child support, the data show a high proportion

(73 percent) of regular payers and only 8 percent of cases where payments had not been made for

the last six months. In the case of broken common-law unions, the proportion of cases in which

there had not been a payment in the last six months is much higher, regardless of whether there

was a private agreement between the spouses (24 percent), or whether a court order was in place

(45 percent). But the most significant result is that agreements that parents described as private

resulted in more regular payments than cases where a court order was in place or was in progress.

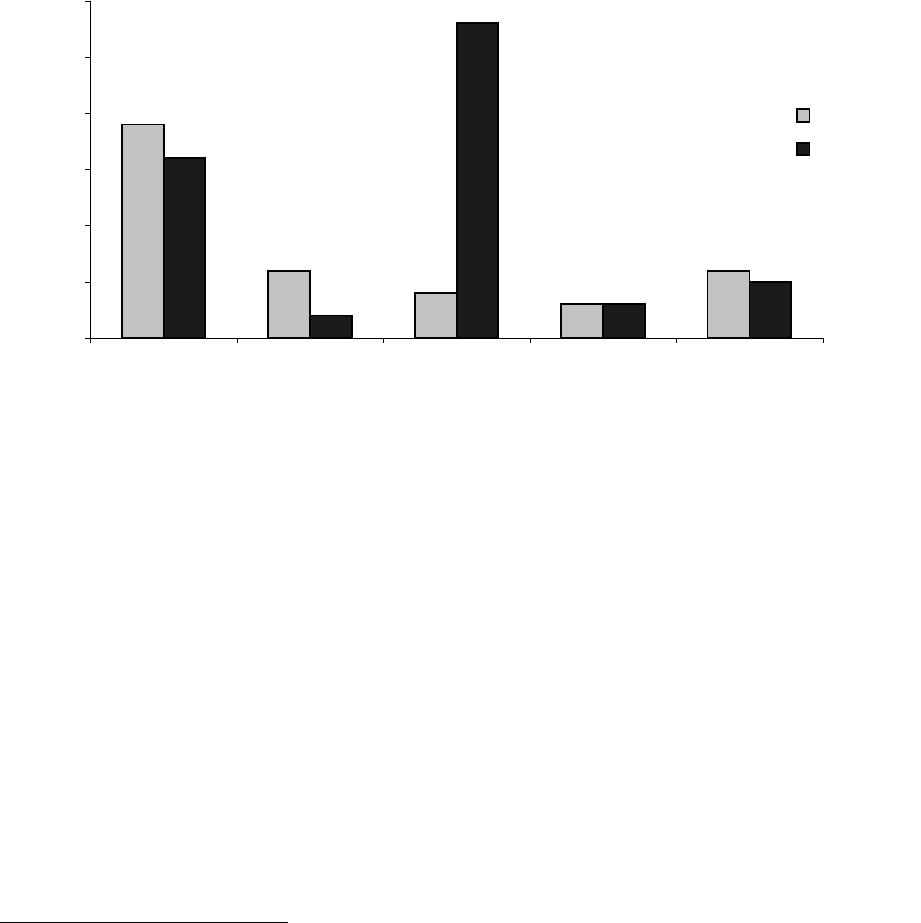

Visiting Patterns and Payment of Child Support

Figure 21 reveals the close association between regularity of payments and frequency of visits.

Among children living with their mother, and for whom child support payments were regular and

on time, close to one-half (48 percent) visited their father on a weekly basis, while only 7 percent

never saw him. In comparison, fathers who did not provide financially for their children on a

regular basis had fewer contacts with them. Only 15 percent of children whose fathers had not

provided child support payments in the last six months saw their fathers weekly and 28 percent

never saw him. The regularity of payments appears strongly related to the likelihood of fathers

- 27 -

maintaining frequent contact with their children, and the impact of this variable remains

important even after controlling for the type of custody and child support arrangements, the type

of union, the level of tension between parents, and the time elapsed since separation.

Figure 21: Visiting Patterns with Father, for Children Living with Mother at Time of

Separation, According to Regularity of Child Support Payments—NLSCY,

Cycle 1, 1994-1995

Never Visits

Visits Irregularly

Visits Every 2 Weeks

Visits Weekly

Regular Payments on Time

Irregular Payments No Payment for 6 Months or More

48%

7%

22%

23%

35%

22%

9%

34%

18%

39%

15%

28%

Source: Marcil-Gratton, N. & C. Le Bourdais (1999). Custody, Access and Child Support:

Findings from The National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth.

- 28 -

APPENDIX

STATISTICS CANADA SURVEYS

National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth (NLSCY)

This is a biennial survey of 25,000 children who were 11 and under when the survey began. The

first cycle was collected in late 1994. The same families will be surveyed every two years for

eight years (four cycles), with additional children (birth to one year old) added each cycle. The

survey has a section entitled “Family History and Custody,” which contains information on

support payments, custody and access to children by non-custodial parents. All sections of the

first and second cycles of the survey have been released. The third cycle of data has been

collected and is presently being released. This survey will provide detailed information on the

changes in custody and access arrangements over time.

Central Registry of Divorce Proceedings (CRDP)

The registry contains data on every divorce application and judgment filed in Canada since 1970.

The Department of Justice Canada enters the information into a database which is edited by the

Health Division of Statistics Canada and published in its annual report on divorces in Canada.

The unit of count is the number of finalized divorces in a calendar year. This report includes

dates of marriage and divorce numbers of children, birth dates of children and custody

arrangements. Some data quality problems have been identified with the information collected

on the type of custody due to varying definitions of “joint custody.”

Survey of Labour Income Dynamics (SLID)

This is a longitudinal survey of households similar in content to the Survey of Consumer

Finances except that the same households are surveyed every two years. Started in 1994, it

collects data on support payments as an element in sources of income. The first cycle results are

now being published. The results will show changes in the levels of support received by

respondents as well as other changes, like those in the population receiving support.

REVENUE CANADA DATA

Tax Statistics

Information is taken from Revenue Canada income tax returns including the number of payers

and recipients of support, as well as the dollar amounts. Through its Statistics Division, Revenue

Canada publishes basic statistical tax data on various characteristics of the returns, such as the

number of returns, the number of persons reporting the different income items and deductions,

and the total amounts reported in those categories. Revenue Canada may also provide the total

incomes of individuals.

- 29 -

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Galarneau, Diane and Jim Sturrock

1997 Family Income After Separation. (Catalogue No. 13-588-MPB, No. 5) Ottawa: Statistics

Canada; Labour and Household Surveys Analysis Division.

Hornick, J.P, Lorne Bertrand and Nicholas Bala

1999 The Survey of Child Support Awards: Preliminary Analysis of Phase 2 Data.

Ottawa: Department of Justice Canada.

J&J Research Associates

1990 Evaluation of the Divorce Act 1985—Phase II: Monitoring and Evaluation.

Ottawa: Department of Justice Canada.

Kerr, Richard & Associates

1999 Social Assistance and Child Support—A Pilot Study.

Ottawa: Department of Justice Canada.

Lindsay, Colin

1992 Lone-parent Families in Canada. (Catalogue No. 89-522E)

Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Marcil-Gratton, Nicole and Céline Le Bourdais

1999 Custody, Access, and Child Support—Findings from the National Longitudinal Survey of

Children and Youth.

Ottawa: Department of Justice Canada.

National Council of Welfare

1997 Poverty Profile 1996. (Catalogue No. H67-1/4-1995E)

Ottawa: Minister of Public Works and Government Service Canada.

Revenue Canada

1994 Taxation Statistics—Analyzing the Returns of Individuals for the 1992 Taxation year and

Miscellaneous Statistics. (Catalogue No. Rv 44-1994) Ottawa.

Revenue Canada

1996 Tax Statistics on Individuals, 1995. Ottawa.

Statistics Canada

1997 “1996 Census: Marital Status, Common-Law Unions and Families”. The Daily.

October 14. <http://www.statcan.ca/Daily/English/971014/d971014.htm>

Statistics Canada

1997 “Divorce in the 1990s.” Health Reports. Vol. 9, (2) (Catalogue No. 82-003-XPB) p. 55.

- 30 -

Statistics Canada

1990 Divorces 1987-1988. (Catalogue No. 82-003S) Ottawa.

Statistics Canada

1991 Divorces 1990. (Catalogue No. 82-003S17) Ottawa.

Statistics Canada

Divorces (1991, 1992, 1993, 1994, 1995). (Catalogue No. 84-213-XPB, 1991, 1992,

1993, 1994, 1995).

Statistics Canada

1996 Marriages 1995. (Catalogue No. 84-212-XPB) Ottawa.

Statistics Canada

1992 Marriages and Conjugal Life in Canada. (Catalogue No. 91-534E) Ottawa.

Statistics Canada

1983 Marriages and Divorces—Vital Statistics. Vol. II (Catalogue No. 84-205).

Statistics Canada

“Shelf Tables: Marriages and Divorces—Vital Statistics 1986.” Unpublished data.

Statistics Canada

Household Surveys Division. “Survey of Consumer Finances.” Unpublished data.

The Vanier Institute of the Family

1996 Canada’s Families—They Count. Ottawa.