A fifty-year look at divorces in

Canada,1970to2020

Released at 8:30 a.m. Eastern time in The Daily, Wednesday, March 9, 2022

Highlights

• The number of divorces recorded in2020(42,933) was the lowest since1973.

• Barriers to accessing court services during the COVID-19pandemic likely contributed to the decrease in

divorce applications and granted divorces in2020.

• The decrease in the divorce rate since1991is linked to the aging of the married population.

• Since the mid-2000s, age-specific divorce rates have been declining most rapidly for young adults while they

have plateaued for persons aged50and over.

• Almost one-third of divorces are now the result of a joint application by both spouses.

• In2019, Canada had the second lowest crude divorce rate among G7countries.

• In the period from2016to2020, divorce rates were highest in Yukon and Alberta and lowest in Nunavut and

Newfoundland and Labrador.

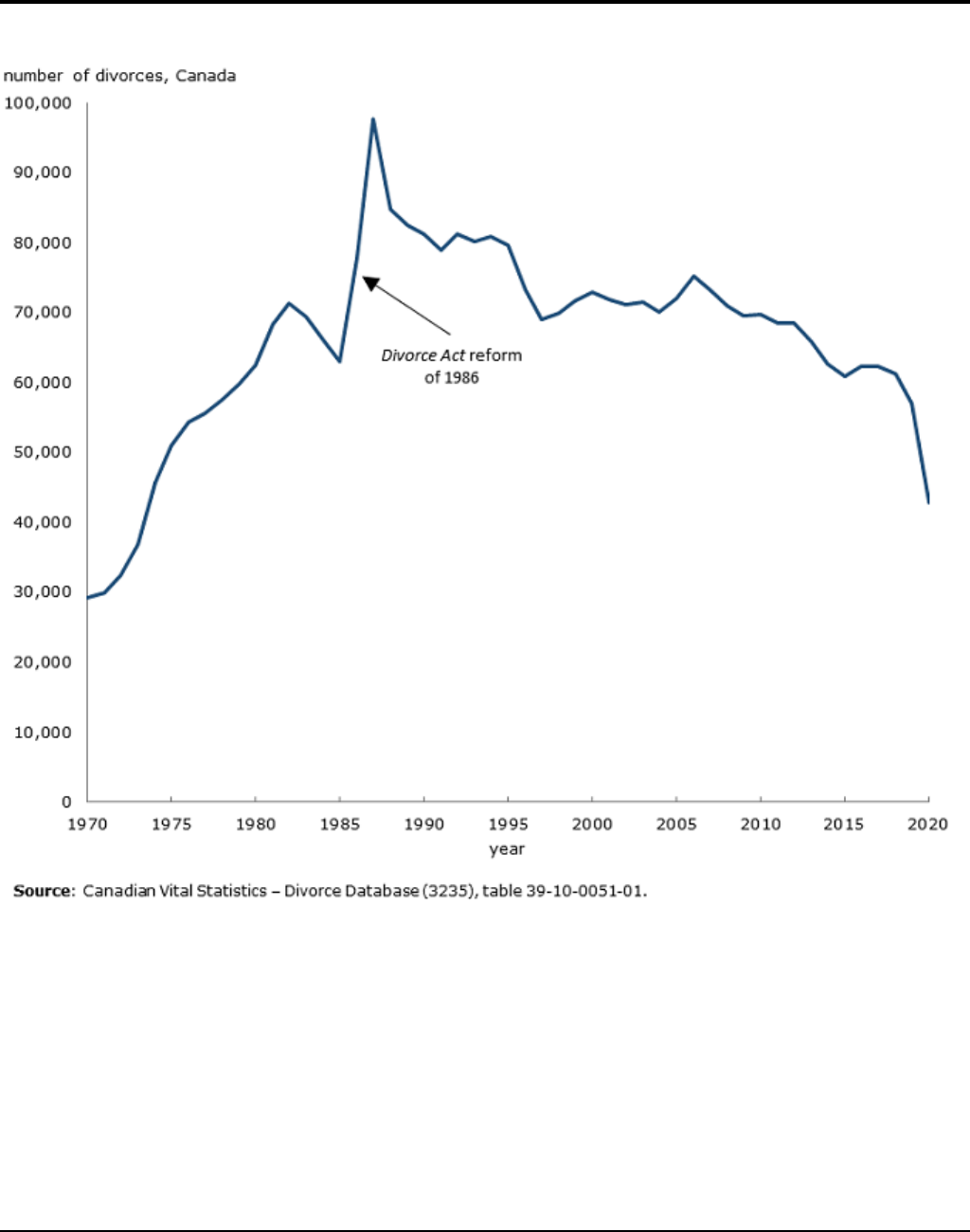

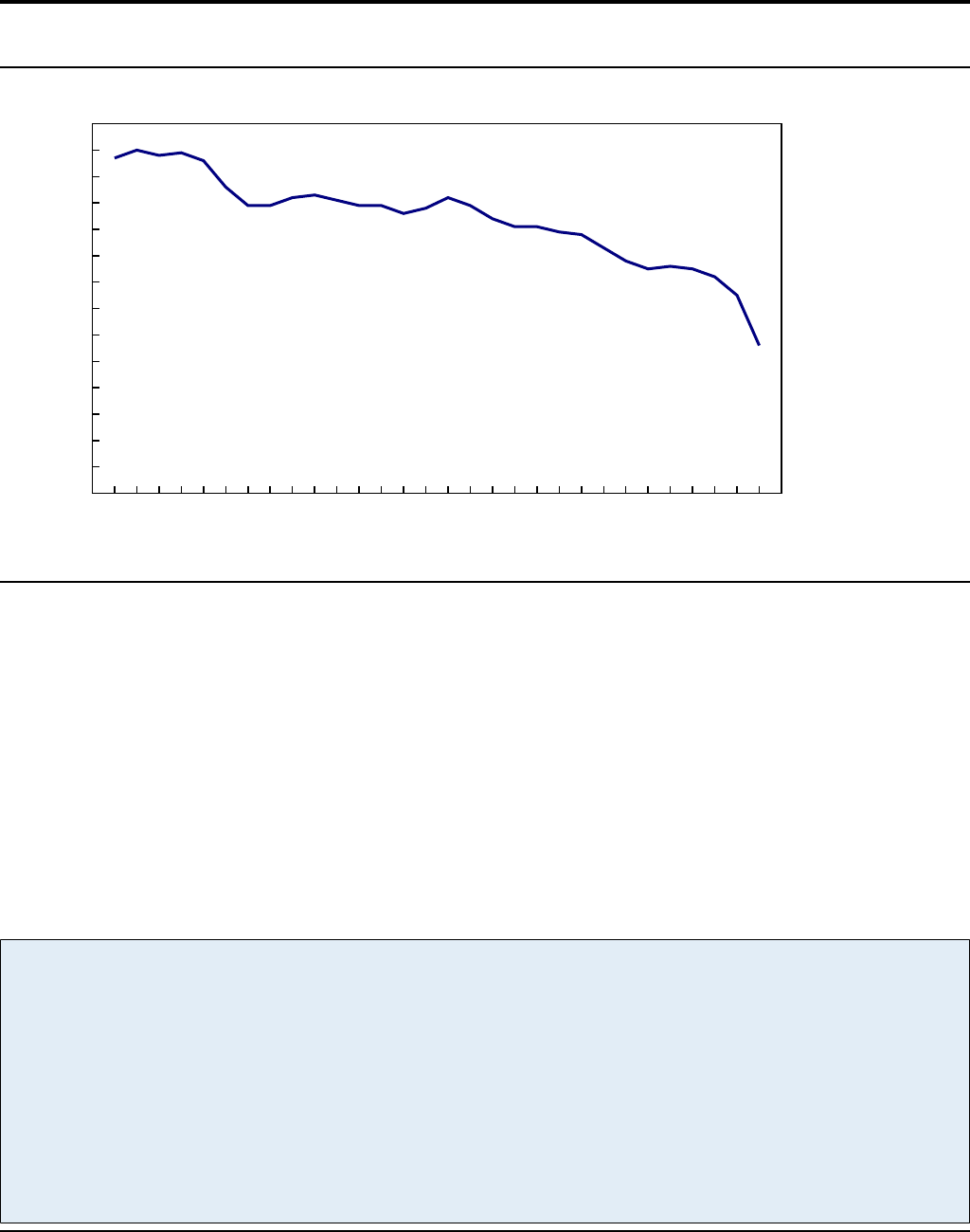

Sharp decrease in divorces between2019and2020

In2020, there were42,933divorces granted in Canada, a sharp decrease from the56,937divorces recorded

in2019. While the number of divorces in the country has been generally declining for many years, this25% annual

drop is the largest since the Divorce Act of1968came into force. Difficulties accessing courts services during the

COVID-19pandemic likely contributed to this decrease which coincides with the onset of the pandemic.

The number of divorces in2020was the lowest since1973and less than half the highest number recorded in1987.

That year,97,773divorces were granted following amendments to the Divorce Act that reduced the minimum period

of separation required before being granted a "no-fault" divorce from three years to one year.

The Daily, Wednesday, March 9, 2022

Component of Statistics Canada catalogue no. 11-001-X

2

Infographic 1– General decline in the number of divorces in the past decades, but sharper

decrease in2020

The pandemic has created obstacles for the processing of divorce cases

Public health measures introduced during the pandemic were likely important drivers of the relatively low number of

divorces recorded in2020. In fact, lockdowns, slowed court proceedings, the adjournment of less urgent cases, and

the temporary closure of some courts created barriers to accessing court services.

The social and economic disruptions associated with the pandemic may also have led to a change in the number of

couples seeking to divorce. However, this specific effect cannot yet be seen in divorce statistics for the year2020.

In the case of 'no-fault' divorce applications—which have traditionally constituted the majority of

applications—couples must separate for at least one year before a divorce may be granted. As a result, the full

impact of these disruptions on the number of divorces will only begin to be seen in2021.

The Daily, Wednesday, March 9, 2022

Component of Statistics Canada catalogue no. 11-001-X

3

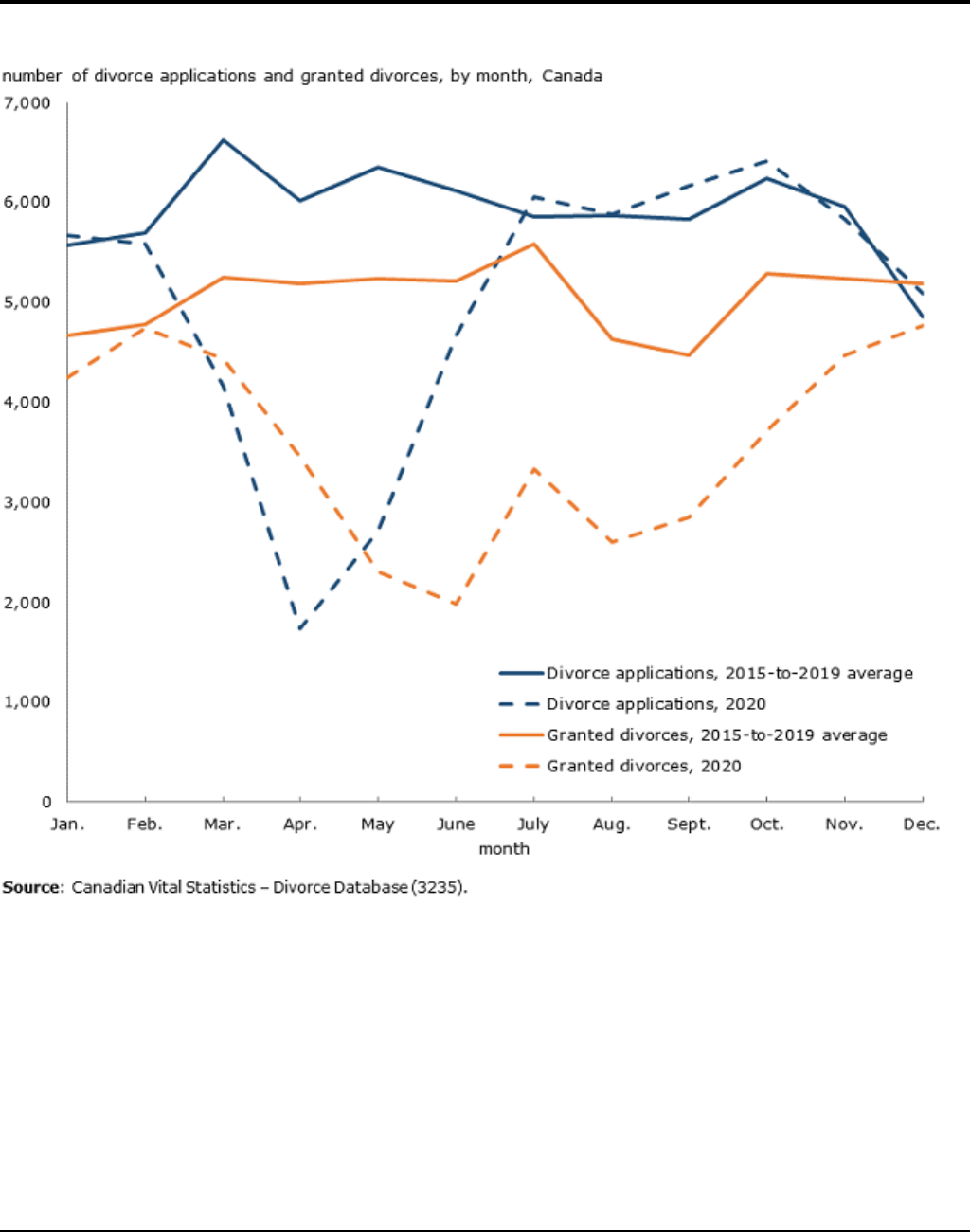

Infographic 2– Sharp decrease in divorce applications and granted divorces in the early months

of the pandemic

The monthly number of divorce applications filed with the courts declined markedly beginning in March2020.

However, by July2020, the number of applications had recovered to a level similar to that of previous years.

The number of divorces granted each month by the courts also fell at the beginning of the pandemic. However,

unlike the number of applications, the number of divorces granted in December2020had yet to return to the level

of recent pre-pandemic years. A similar pattern was found in a case study of monthly divorces in five American

states.

In addition, the time elapsed between the filing of the divorce application and the granting of the divorce has

increased since the start of the pandemic. While the median duration of this process was4.8months for divorces

granted in2018and2019, it increased by a month in2020(5.8months).

The Daily, Wednesday, March 9, 2022

Component of Statistics Canada catalogue no. 11-001-X

4

Fewer divorces in all provinces in2020

All provinces experienced a decrease in the number of divorces between2019and2020. The decrease was

particularly strong in Ontario (-36%). In the other provinces, the decrease was between11% (New Brunswick)

and22% (Alberta).

In contrast, the number of divorces remained stable in the territories, with the exception of Nunavut where annual

fluctuations are common given the low number of divorces granted each year.

The Daily, Wednesday, March 9, 2022

Component of Statistics Canada catalogue no. 11-001-X

5

Table 1

Drop in the number of divorces in all provinces between 2019 and 2020

2019 2020 2019 to 2020

number of divorces

% change

Canada 56,937 42,933 -24.6

Newfoundland and Labrador 729 618 -15.2

Prince Edward Island 240 204 -15.0

Nova Scotia 1,395 1,149 -17.6

New Brunswick 1,185 1,056 -10.9

Quebec 9,681 8,559 -11.6

Ontario 22,377 14,223 -36.4

Manitoba 2,037 1,782 -12.5

Saskatchewan 1,893 1,566 -17.3

Alberta 8,673 6,801 -21.6

British Columbia 8,589 6,849 -20.3

Yukon 81 78 -3.7

Northwest Territories 45 45 0.0

Nunavut 12 3 -75.0

Source(s): Canadian Vital Statistics – Divorce Database (3235), table 39-10-0051-01.

Divorce statistics reflect only part of all union dissolutions

A divorce is a legal process that ends a marriage. Therefore, divorce statistics do not cover the separations of

married couples nor the dissolutions of common-law couples.

Most married couples separate before filing for divorce, and some separated couples may never legally

divorce. Moreover, since the share of common-law couples—for whom divorce does not apply—has increased

from6% of all couples in Canada in1981to21% in2016, divorce statistics increasingly underestimate total

conjugal instability. This is particularly true in Quebec and the territories, where common-law unions are more

prevalent.

Although divorce statistics do not reflect all union dissolutions, they provide valuable information on the state of

marriage as an institution in Canada. They are also the only annual statistics available on union dissolutions,

since no official record is kept of the separation of married or common-law couples.

The2017General Social Survey on the family provides the most recent survey-based information on the

separation of married and common-law couples.

The2021Census of Population will provide statistical information on the number of Canadians currently

divorced, separated, married or living common law.

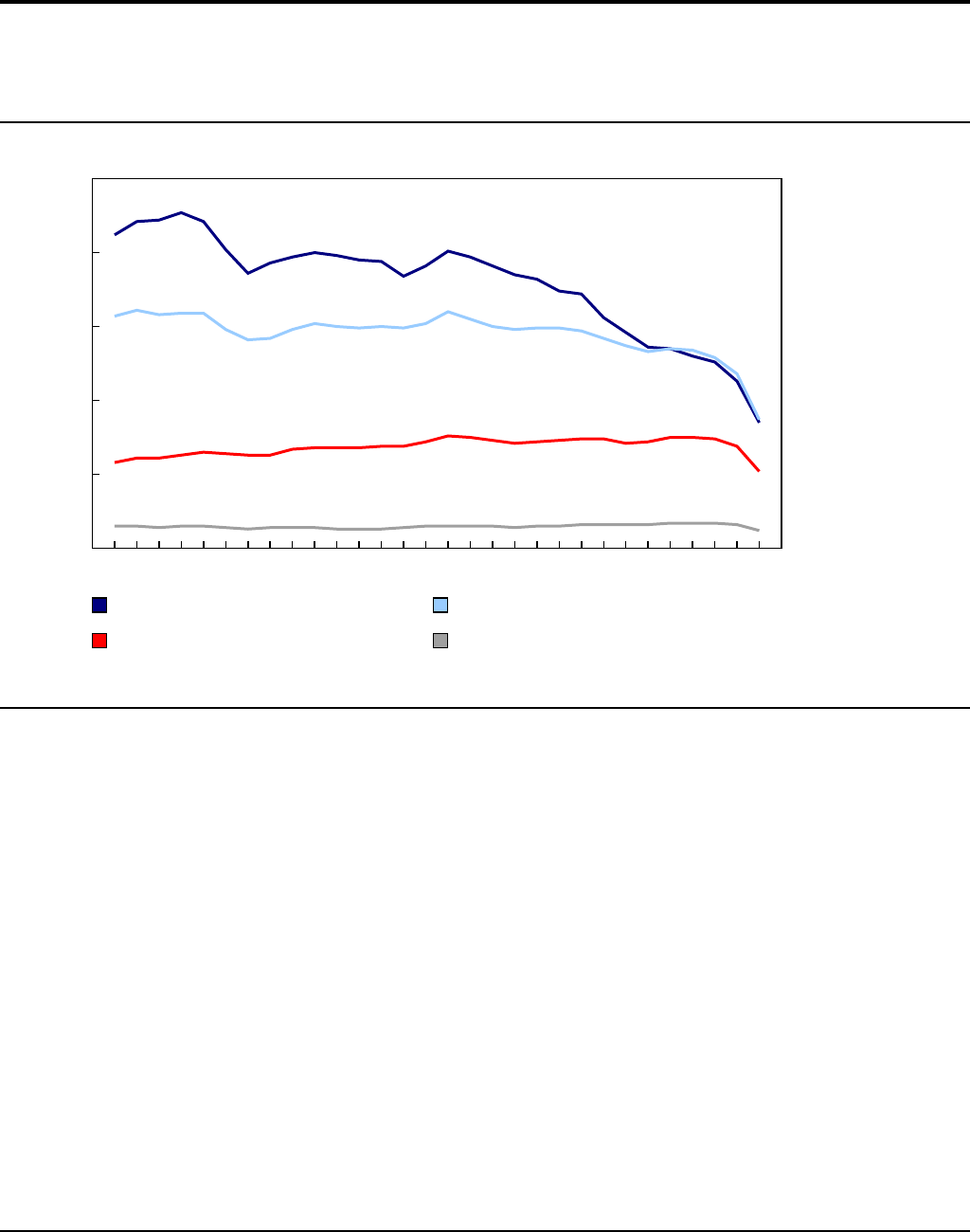

Falling divorce rate since1991is linked to the aging of the married population

The decrease in the number of divorces over the last three decades has occurred despite growth in the population

at risk of divorce, that is, married persons. As a result, the divorce rate—which corresponds to the number of

persons who divorce per1,000married persons—decreased from12.7per1,000in1991to7.5per1,000in2019,

and fell further to5.6per1,000in2020.

The Daily, Wednesday, March 9, 2022

Component of Statistics Canada catalogue no. 11-001-X

6

Chart 1

Steady decline of the divorce rate since1991

number of persons who divorced per 1,000 married persons, Canada

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

1991 1994 1997 2000 2003 2006 2009 2012 2015 2018

Source(s):Canadian Vital Statistics – Divorce Database (3235), table 39-10-0051-01.

Two key societal changes have contributed to the general decrease in the divorce rate observed over the last three

decades: aging of the married population and a lowered tendency to divorce among younger married adults in

particular.

The married population is getting older because of the general population aging, but also because younger

generations of Canadians are choosing common-law unions more often (see Box Divorce statistics reflect only part

of all union dissolutions) and, when they do marry, they do so at an older age than the generations that preceded

them. Since age-specific divorce rates are generally lower among older adults than among younger adults, the

aging of the married population has led to a decline in the divorce rate.

Also, age-specific divorce rates have not changed uniformly. While divorce rates among married persons younger

than50remain higher than those among older persons, they have declined markedly, especially in recent years.

Demographers and sociologists often attribute this decrease, also seen in other countries, to a growing selectivity of

marriage. That is, as proportionally fewer persons choose to marry, those that do might increasingly come from a

distinct subgroup that has some combination of characteristics that favours a long-lasting marriage.

New today!

Today, Statistics Canada unveils a series of new tables: Number of divorces and divorce indicators

(39-10-0051-01), Mean age and median age at divorce and at marriage, for persons who divorced in a given

year, by sex or gender (39-10-0052-01), Number of persons who divorced in a given year and divorce rate

per1,000married persons, by age group and sex or gender (39-10-0053-01), and Number of divorces and

divorce rate per1,000marriages, by duration of marriage (39-10-0054-01).

As part of Statistics Canada's commitment to increase Canadians' statistical literacy and to make this

information publicly available, the new tables offer users the ability to search, use and analyze information on

various indicators related to divorces.

The Daily, Wednesday, March 9, 2022

Component of Statistics Canada catalogue no. 11-001-X

7

Chart 2

Over the last thirty years, age-specific divorce rates fell for young adults, but rose slightly for

older adults. The pandemic-related decrease in2020is observed in all age groups

number of persons who divorced per 1,000 married persons, Canada

0

5

10

15

20

25

1991 1994 1997 2000 2003 2006 2009 2012 2015 2018

15 to 34 years 35 to 49 years

50 to 64 years 65 years and over

Source(s):Canadian Vital Statistics – Divorce Database (3235), table 39-10-0053-01.

Growth in "grey divorce" halted

In comparison with younger adults, divorce among persons aged50years and older, sometimes dubbed "grey

divorce," remains a relatively rare event. The divorce rate in this age group did rise by26%

between1991and2006(from4.2to5.3per1,000) but has remained fairly stable since, notwithstanding the lower

values for2020. The rise of grey divorce in Canada, which coincided with the arrival of the baby-boom cohort into

this age group, was however quite modest compared with the doubling of levels observed in the United States over

a similar period.

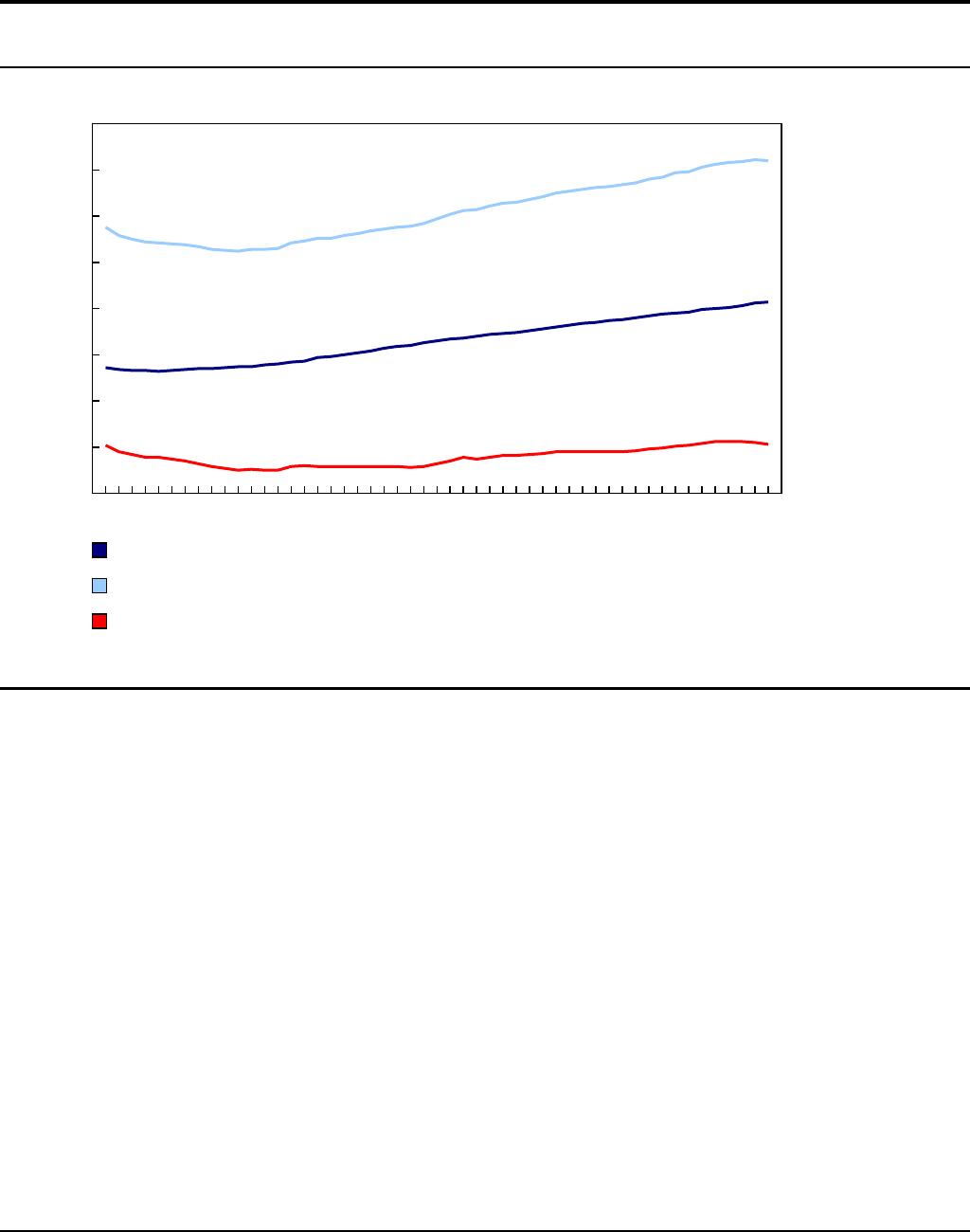

Divorces occurring at increasingly older ages

The average age at divorce has been rising almost continuously since it reached a low point of36.2years in1980.

More recently, it has been closer to46years.

This gradual increase in the average age at divorce is mainly the result of a continuous increase in the age at

marriage of those who divorce, but also of an increase in the duration of marriages ending in divorce.

The Daily, Wednesday, March 9, 2022

Component of Statistics Canada catalogue no. 11-001-X

8

Chart 3

Steady rise in the average age at divorce

mean age or mean duration in years, Canada

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

50

1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020

Age at marriage of the persons who divorced

Age at divorce

Duration of marriage at divorce

Source(s):Canadian Vital Statistics – Divorce Database (3235), table 39-10-0052-01.

The average age at marriage for persons who divorced was23.7years in1980, increasing to30.7years in2020.

Similarly, the average duration of marriages ending in divorce rose from12.5years in1980to15.3years in2020.

Because women often marry at a younger age than men, women also divorce at a younger age. In2017, the latest

year for which this information is available nationally, the average age at divorce was44.5years for women

and47.0years for men.

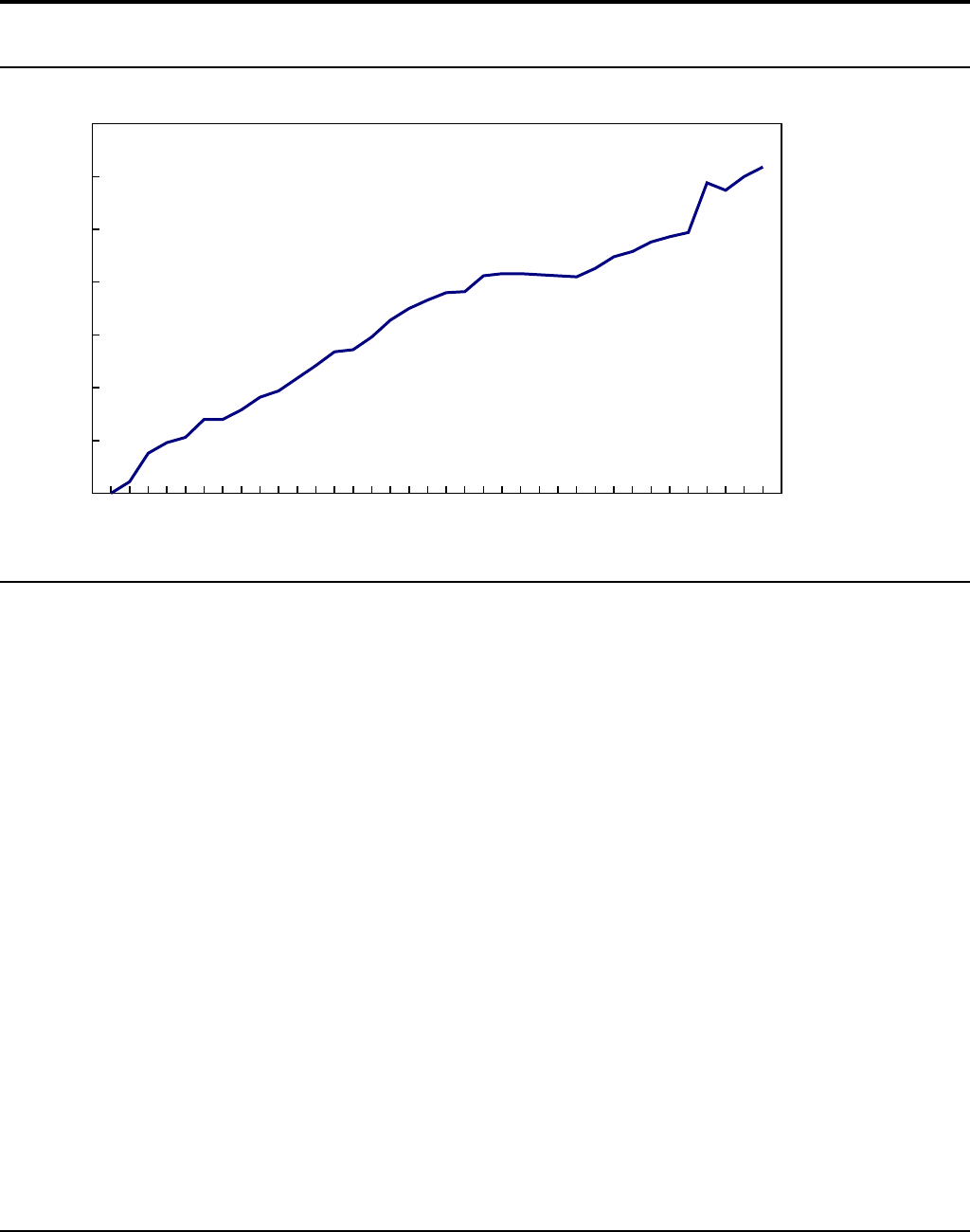

Almost one-third of divorces are now the result of a joint application by both spouses

Following the revision of the Divorce Act that came into force in1986, it became possible for both spouses to file

jointly for a divorce. The proportion of couples who file jointly has grown steadily from4% in1987to31% in2020.

This suggests a growing tendency among couples to mutually agree upon the broad terms of their divorce before

proceeding with a formal application to the courts.

The Daily, Wednesday, March 9, 2022

Component of Statistics Canada catalogue no. 11-001-X

9

Chart 4

Proportion of divorce applications filed jointly continues to increase

% of applications that are filed jointly, Canada

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

1985 1988 1991 1994 1997 2000 2003 2006 2009 2012 2015 2018

Source(s):Canadian Vital Statistics – Divorce Database (3235), table 39-10-0051-01.

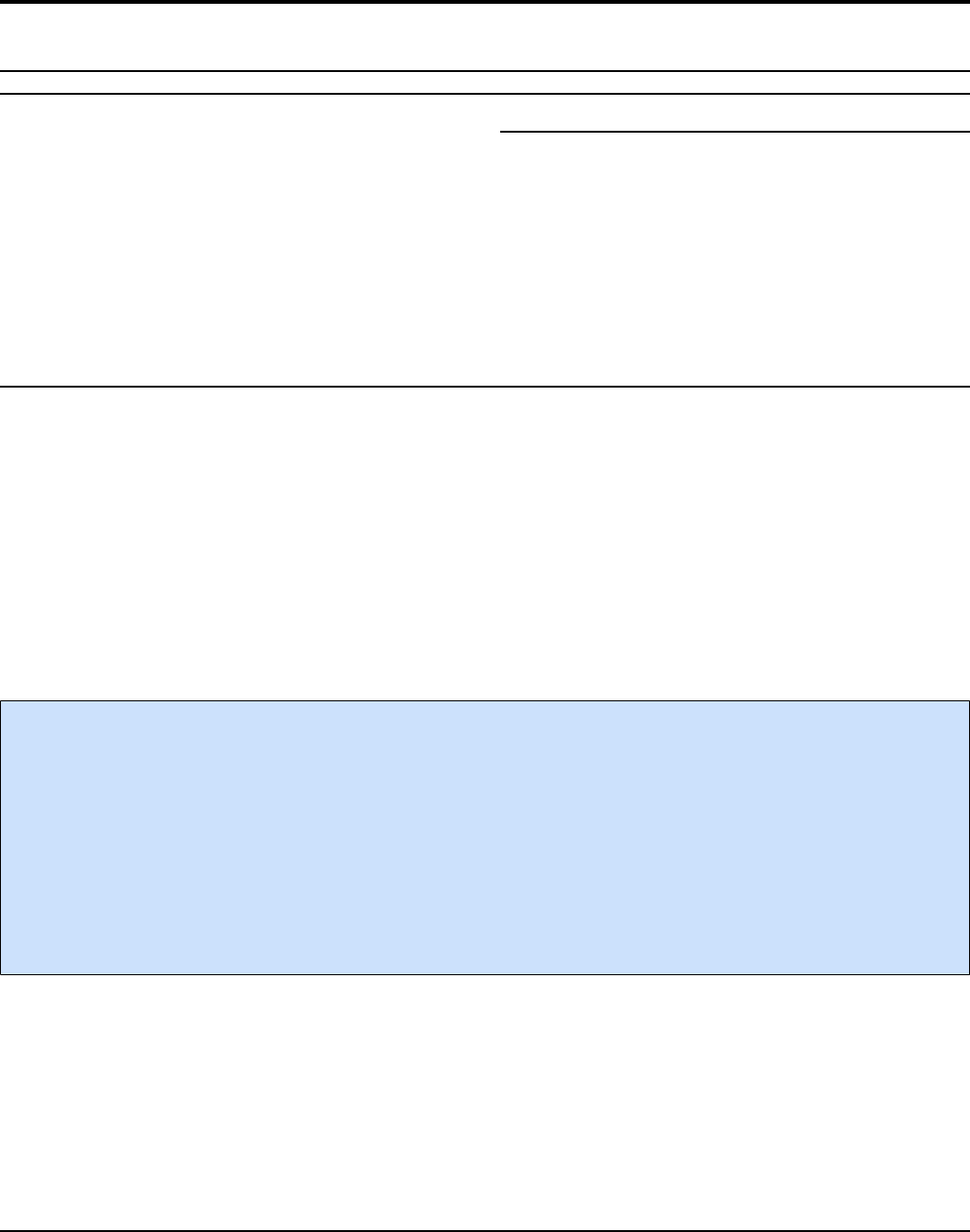

In2019, Canada has the second lowest crude divorce rate among G7countries

Given recent trends, Canada now has a comparatively low number of divorces. For instance, in2019, among

G7countries, Canada had the second lowest crude divorce rate (CDR) after Italy and a CDR44% lower than the

United States (the highest in the group). Canada's CDR was also below the average of the Organisation for

Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries and of the European Union.

Note that these comparisons are based on the CDR, which corresponds to the number of divorces

per1,000persons (of all ages, married or not). While the CDR is the most widely available divorce indicator, it does

not account for international variations in the share of the population that is married and thus at risk of divorcing. For

instance, the large decline of the CDR in Canada between1995and2019is partly due to the growth of

common-law unions during this period.

The Daily, Wednesday, March 9, 2022

Component of Statistics Canada catalogue no. 11-001-X

10

Chart 5

From an international perspective, there are relatively few divorces in Canada

Russian Federation

China

United States

Sweden

OECD

Australia

France

European Union

Germany

United Kingdom

New Zealand

Japan

Canada

Italy

Mexico

Ireland

0 1 2 3 4 5

number of divorces per 1,000 persons

1995 2019

Note(s):Data presented for2019are from an earlier year for Russia (2013), France (2016), the United Kingdom (2016), Mexico (2018), and Ireland

(2017).2019data for the United States exclude the states of California, Hawaii, Indiana, Minnesota, and New Mexico. Data for the European Union are an average

of the27member states as of2020; the2019value is an estimate. Data for the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) are an average

of36member states using data from previous years when2019was unavailable.

(...)not applicable

Source(s):Canadian Vital Statistics – Divorce Database (3235), table 39-10-0051-01,2020China Statistical Yearbook, Eurostat's divorce indicators, OECD's

marriage and divorce rates.

Wide but declining variation in divorce rates across the provinces and territories

Echoing the situation at the national level, the divorce rate for married persons followed a downward trend in every

province and territory from1991to2020. Although the variation in divorce rates between the provinces and

territories has decreased over time, there are still significant differences across the country. Over the5-year period

from2016to2020, the divorce rate was highest in Yukon (13persons divorced per1,000married persons) and

Alberta (10per1,000married persons), while it was lowest in Nunavut (2per1,000married persons) and

Newfoundland and Labrador (6per1,000married persons).

The Daily, Wednesday, March 9, 2022

Component of Statistics Canada catalogue no. 11-001-X

11

Table 2

Decline in divorce rates in all the provinces and territories in the last decades

1991 to 1995 2016 to 2020

number of persons who divorced per 1,000 married persons

Canada 12.8 7.7

Newfoundland and Labrador 7.9 6.2

Prince Edward Island 8.8 6.6

Nova Scotia 11.3 7.3

New Brunswick 9.4 7.4

Quebec 14.3 8.0

Ontario 12.2 7.2

Manitoba 11.4 7.1

Saskatchewan 10.6 7.7

Alberta 14.1 9.7

British Columbia 14.2 7.5

Yukon 17.7 12.8

Northwest Territories

1

11.0 7.5

Nunavut

1

11.0 2.4

1. For 1991 to 1995, Nunavut and Northwest Territories were a single territory.

Source(s): Canadian Vital Statistics – Divorce Database (3235).

Looking ahead

The number of divorces expected for2021will depend largely on two factors:1) whether the pandemic prompted a

lower or higher number of married couples to separate in2020than would have normally been the case, and2)

whether the family court system was able to process divorce applications at levels similar to pre-pandemic years or

even to surpass these levels to catch up on cases that were delayed in2020.

In2021, the first substantial amendments to the Divorce Act in over20years came into force. This revision, which

promotes the best interests of children, does not modify the grounds on which divorce can be sought. However, it

does encourage out-of-court dispute resolution, including family mediation, which could reduce the length of the

divorce process and increase the proportion of joint applications.

Note to readers

Today, Statistics Canada is releasing new data on divorces for the years2009to2020. Data for2019and2020are considered

preliminary and the number of divorces for these years may be underestimated. Revised data for the years1970to2008are also being

released.

These statistics are from the Canadian Vital Statistics - Divorce Database, a program that processes information collected from the

Department of Justice Canada's Central Registry of Divorce Proceedings (CRDP). The CRDP maintains a record of all divorce

applications filed with courts across the country since the Divorce Act came into force on July2,1968.

The information that the CRDP is mandated to collect from the courts has varied over the years. In2013, for example, the CRDP stopped

collecting data on the date of separation, reasons for divorce, number of dependents and parenting (child custody) arrangements.

The Daily, Wednesday, March 9, 2022

Component of Statistics Canada catalogue no. 11-001-X

12

Available tables:39-10-0051-01 to39-10-0054-01 .

Definitions, data sources and methods: survey number 3235.

For more information, or to enquire about the concepts, methods or data quality of this release, contact us

(toll-free1-800-263-1136;514-283-8300; [email protected]) or Media Relations