Congress Creates the Bill of Rights consists of

three elements: a mobile application for tablets,

an eBook, and online resources for teachers and

students on the Center for Legislative Archives

website (http://www.archives.gov/legislative/

resources/bill-of-rights.html). Each provides a

distinct way of exploring how the First Congress

proposed amendments to the Constitution in 1789.

This PDF contains all the content of the app

divided into four sections:

• Get the Background (Part I);

• Go Inside the First Congress (Part II A);

• Amendments in Process (Part II B); and

• Join the Debate and Appendix (Part III).

Each part is sized so that it can be easily down -

loaded or printed on a wide variety of devices.

Center for Legislative Archives

National Archives

National Archives Trust Fund Publication

Foundation for the National Archives

Funding provided by

The Chisholm Foundation

The Dyson Foundation

Humanities Texas

Designed and produced by Research & Design, Ltd.,

Arlington, Virginia

2

Congress Creates the Bill of Rights

3

Go Inside the First Congress

Title Page. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

Project Description . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

Contents . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

Go Inside the First Congress (Part II A) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

Congress Seeks Compromise . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

Leaders of the House Debate . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

The Champion of Amendments . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

James Madison (1751–1836) Virginia . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

Federalist Position on Amendments . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

Fisher Ames (1758–1808) Massachusetts. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

Roger Sherman (1721–1793) Connecticut . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

James Jackson (1757–1806) Georgia. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

Anti-Federalist Position on Amendments. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

Aedanus Burke (1743–1802) South Carolina . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

Thomas Tudor Tucker (1745–1828) South Carolina . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

Elbridge Gerry (1744–1814) Massachusetts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

Issues and Positions. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

Should the Constitution be amended? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

Should the House of Representatives have few or many members? . . . . . . . . . . 19

Should the people have the authority to instruct representatives? . . . . . . . . . . . 20

Should the federal Bill of Rights apply to the states?. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

Should the federal taxation power be further limited? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

4

The Senate Markup . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23

Close-up on Compromise . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

August 24, 1789 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

September 3, 1789 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30

September 3, 1789 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

September 4, 1789 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

September 9, 1789 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

September 14, 1789 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

September 24, 1789 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

October 2, 1789 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36

Get the Background

6

The struggle over the Bill of Rights was one of many contested issues in the First Congress.

Through compromise, the House and Senate demonstrated that the Constitution could be

safely amended to protect the basic rights of citizens and correct perceived defects.

A fundamental divide existed between Federalists and Anti-Federalists on the question of

amendments to the Constitution. Yet, James Madison found areas of common ground to build

support for a set of amendments. He displayed his political genius by focusing on proposals

that could win the support of a two-thirds majority in each house of Congress, and ratification

by three-quarters of the states. Madison embraced the need to change the new charter in order

to keep the majority of its provisions intact, and he skillfully used the self-correcting measures

in Article V of the Constitution to amend it.

Article V sets a high bar and defines a unique process to propose and ratify amendments.

These requirements include congressional passage by two-thirds majorities in both houses.

Yet within the House and the Senate, and between those two chambers, many of the proce-

dures, tactics, and tools remain the same as the normal legislative process for moving

bills through the chambers to enact laws. This hard work of compromise between the House

and the Senate is revealed in a compelling document, the Senate Revisions to the House Pro-

posed Amendments to the U.S. Constitution (referred to as the Senate Mark-up).

The Founders saw Congress as the forum where representatives of the people and of the states

would reach decisions through deliberation and debate on issues of national importance. With

Madison’s able guidance, the First Congress was able to reconcile differences and set in motion

the ratification of the Bill of Rights.

Go Inside the First Congress

7

Go Inside the First Congress

The House of Representatives debated the Bill of Rights between June 8 and September 24,

1789, when the House voted on its final version of amendments. House debate was shaped by

the extreme reluctance, if not the open hostility, of the members towards Madison’s version of

amendments. Despite this opposition, Madison’s determination and skill guided the

amendments to House approval by a two-thirds vote.

The Champion

of Amendments

James Madison

Virginia

Anti-Federalist Position

on Amendments

Aedanus Burke

South Carolina

Thomas Tudor Tucker

South Carolina

Elbridge Gerry

Massachusetts

Federalist Position

on Amendments

Roger Sherman

Connecticut

James Jackson

Georgia

Fisher Ames

Massachusetts

8

The Champion of Amendments

Go Inside the First Congress

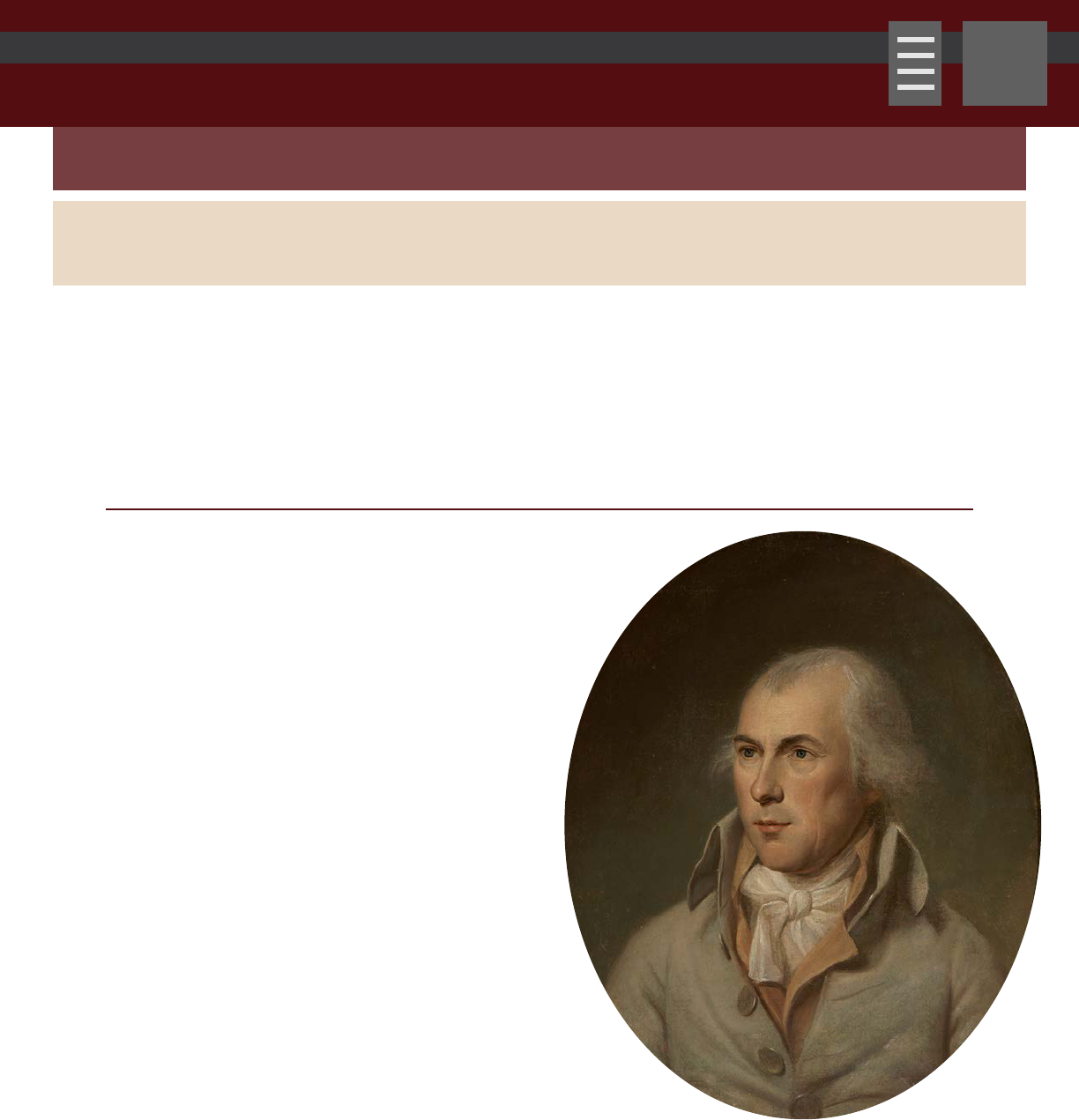

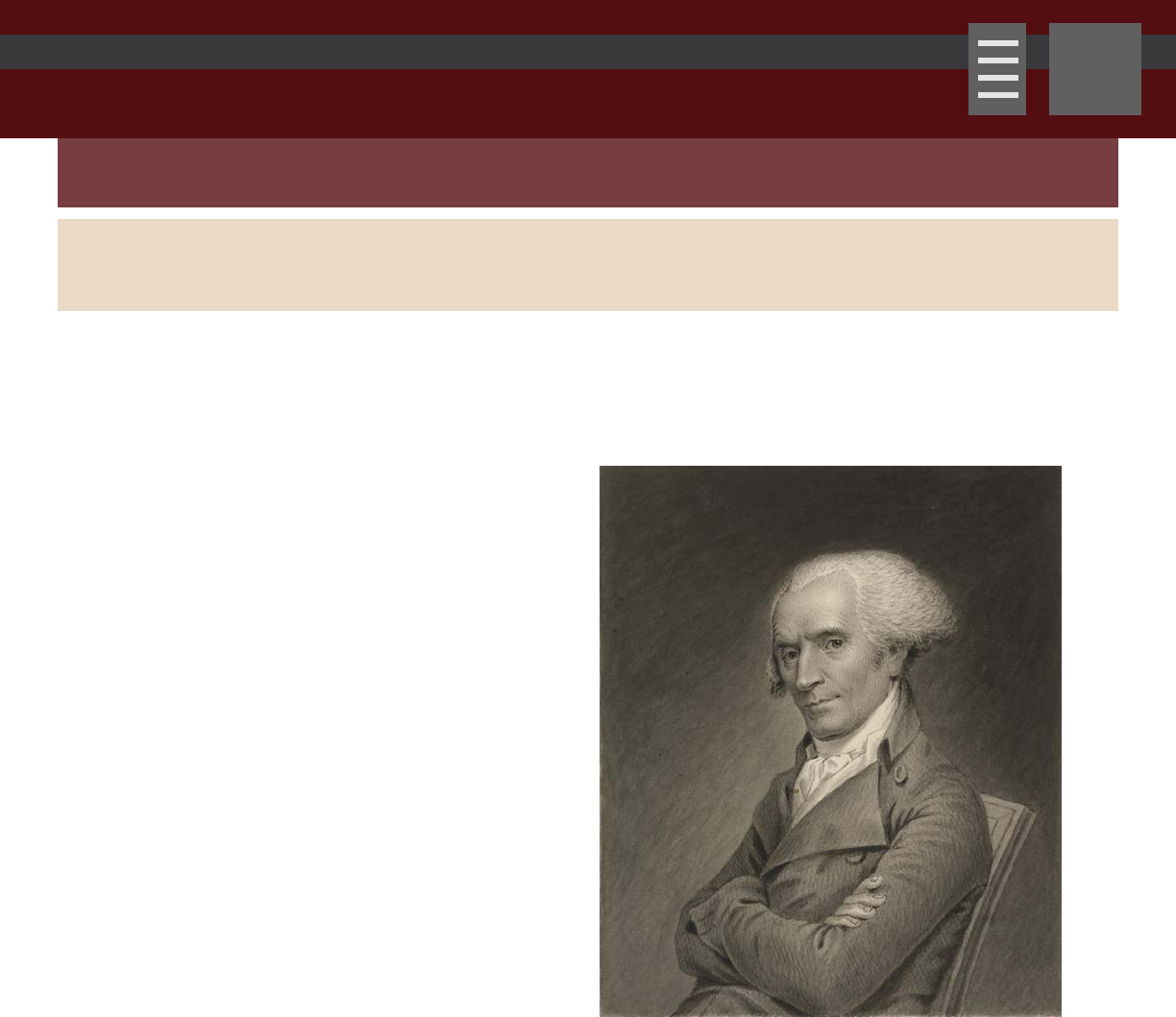

James Madison played a critical role as instigator of the discussion on amendments, which

many members wished to avoid. He put together a carefully crafted, lawyerly speech that

called on the House to “expressly declare the great rights of mankind secured under this

Constitution.”

Born in Virginia, James Madison trained as a

lawyer at Princeton before settling in Orange

County, Virginia. He represented the county

in Virginia’s revolutionary and legislative

bodies. He also represented Virginia in the

Confederation Congress and at the Federal

Convention. He promoted ratification of the

Constitution in the press and as a delegate to

the state convention. Madison was the

author of the constitutional amendments

considered by the House, and the floor

leader who directed their passage. He

believed that by passing his version of

amendments, he could satisfy the public call

to protect rights without endangering the

Constitution and weakening the federal

government.

James Madison by Charles Willson Peale

Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma

9

Federalist Position on Amendments

When the first Congress convened, the Federalist-dominated House opposed amending

the Constitution. Federalists generally believed that a bill of rights was unnecessary in a

government of delegated powers. They were suspicious that the Anti-Federalists’ primary

motive was to undo critical provisions in the Constitution before the new government could be

put into effect.

As the session progressed, Federalists came to realize that Madison’s amendments

neither weakened the federal government nor prevented it from fulfilling its national

responsibilities. They voted for Madison’s amendments, but without much enthusiasm.

Joining Madison as leaders of the debate were Federalists Roger Sherman of Connecticut,

Fisher Ames of Massachusetts, and James Jackson of Georgia.

Go Inside the First Congress

10

Federalist Position on Amendments

Go Inside the First Congress

Fisher Ames by James Sharples

National Portrait Gallery,

Smithsonian Institution/Art Resource, NY

Ames was a Harvard-educated lawyer from

Dedham, Massachusetts, who served in the

Massachusetts House of Representatives

before being elected as a Federalist to the

First Congress. As a member of the

Massachusetts convention, he ardently

supported ratification. He was opposed to

amending the Constitution, noting, “There

would be no limits to the time necessary to

discuss the subject … the session would not

be long enough.”

11

Federalist Position on Amendments

Go Inside the First Congress

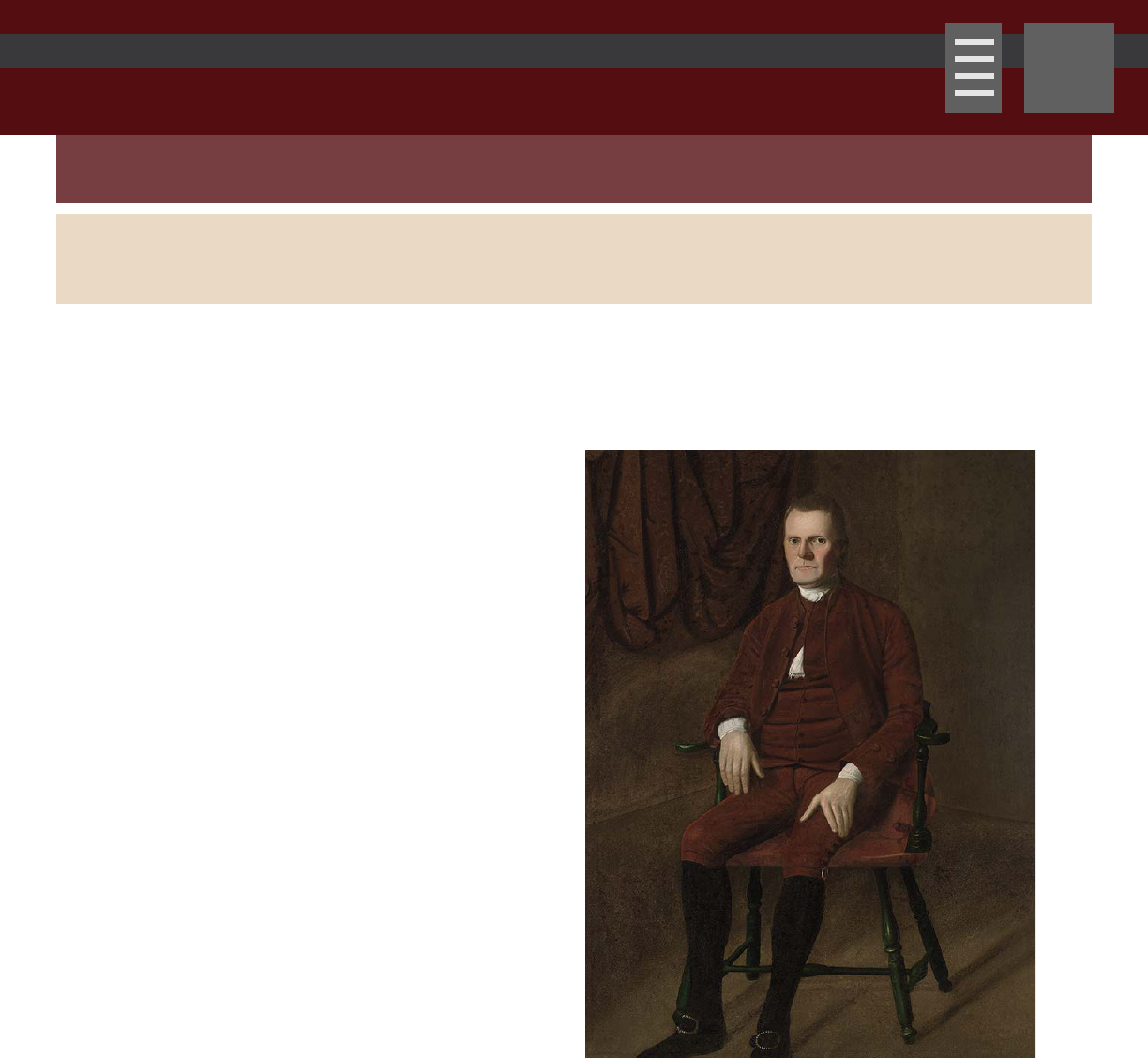

Roger Sherman by Ralph Earl

Yale University Art Gallery

Born in Massachusetts, Sherman settled in

New Haven, Connecticut, where he was a

publisher, lawyer, merchant, judge, and

municipal and state officeholder. Sherman

served for many years in both the

Continental Congress, where he signed the

Declaration of Independence, and the

Confederation Congress. He assumed an

important role at the Federal Convention

and actively supported ratification in both

the press and the state convention. Sherman

played a critical role in the history of the Bill

of Rights when he proposed that the

amendments be added to the end of the

Constitution rather than written into its text,

as Madison had proposed.

12

Federalist Position on Amendments

Go Inside the First Congress

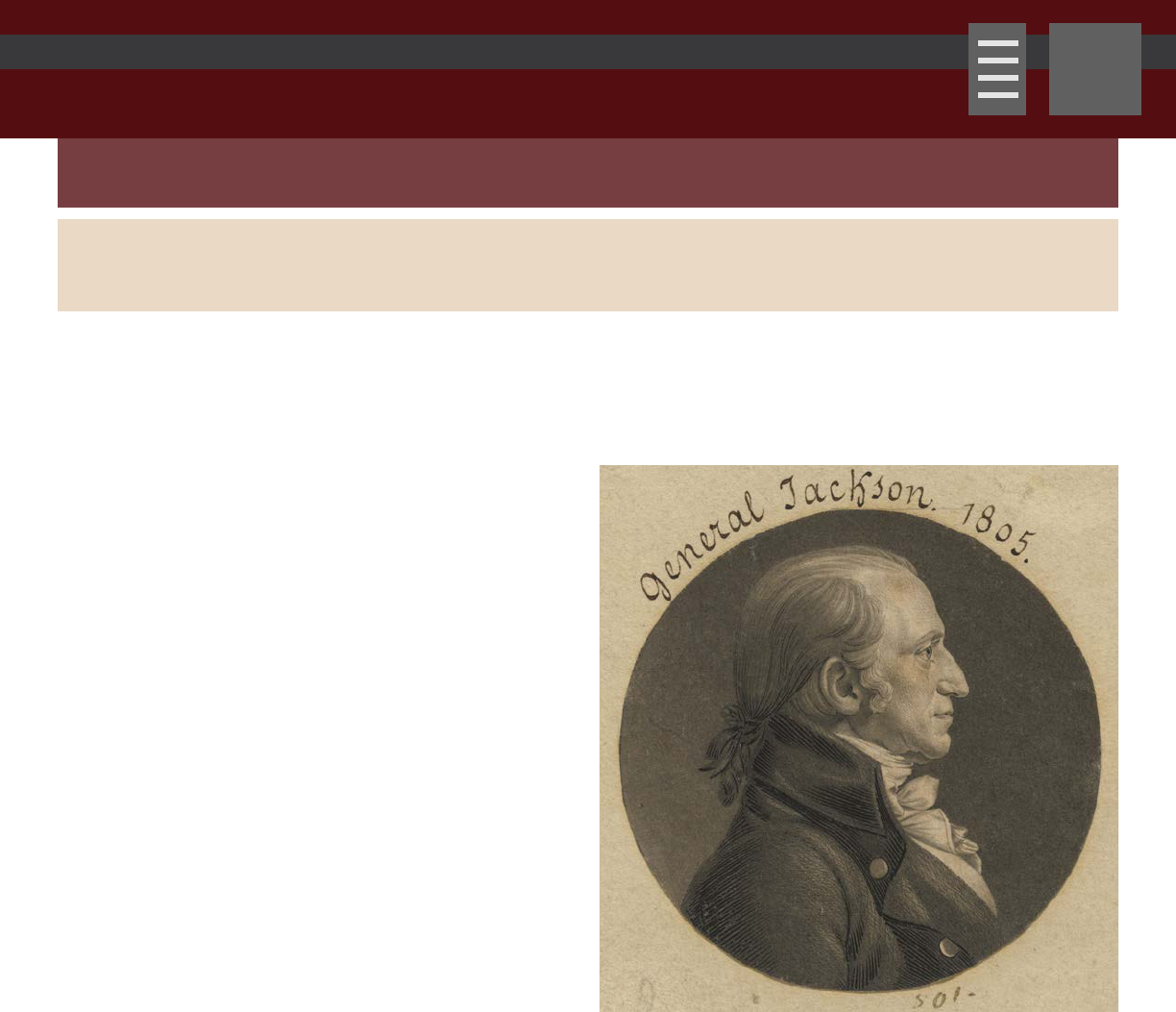

James Jackson by Charles B.J. Févret de Saint-Mémin

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution/Art Resource, NY

Born in England, James Jackson immigrated

to Savannah, Georgia, where he became a

planter and lawyer. He served in the state

assembly and was elected as a Federalist to

the First Congress. Jackson adamantly

opposed amending the Constitution,

remarking, “This is not the time for bringing

forward amendments.”

13

Anti-Federalist Position on Amendments

Go Inside the First Congress

Anti-Federalists wanted to add amendments to reduce the federal government’s powers.

These amendments took two forms: structural amendments that would transfer powers back

to the states, and rights-related amendments that would define fundamental freedoms

protected from federal government interference.

The Anti-Federalists proposed amendments designed to reduce Congress’s power to tax,

replace congressional control of federal elections with state control, eliminate the federal

court system, limit the powers of the president, and place restrictions on a standing army.

The Anti-Federalists believed that Madison had selected the least useful amendments from

those proposed by the states, and they consistently voted against his version of amendments.

14

Anti-Federalist Position on Amendments

Go Inside the First Congress

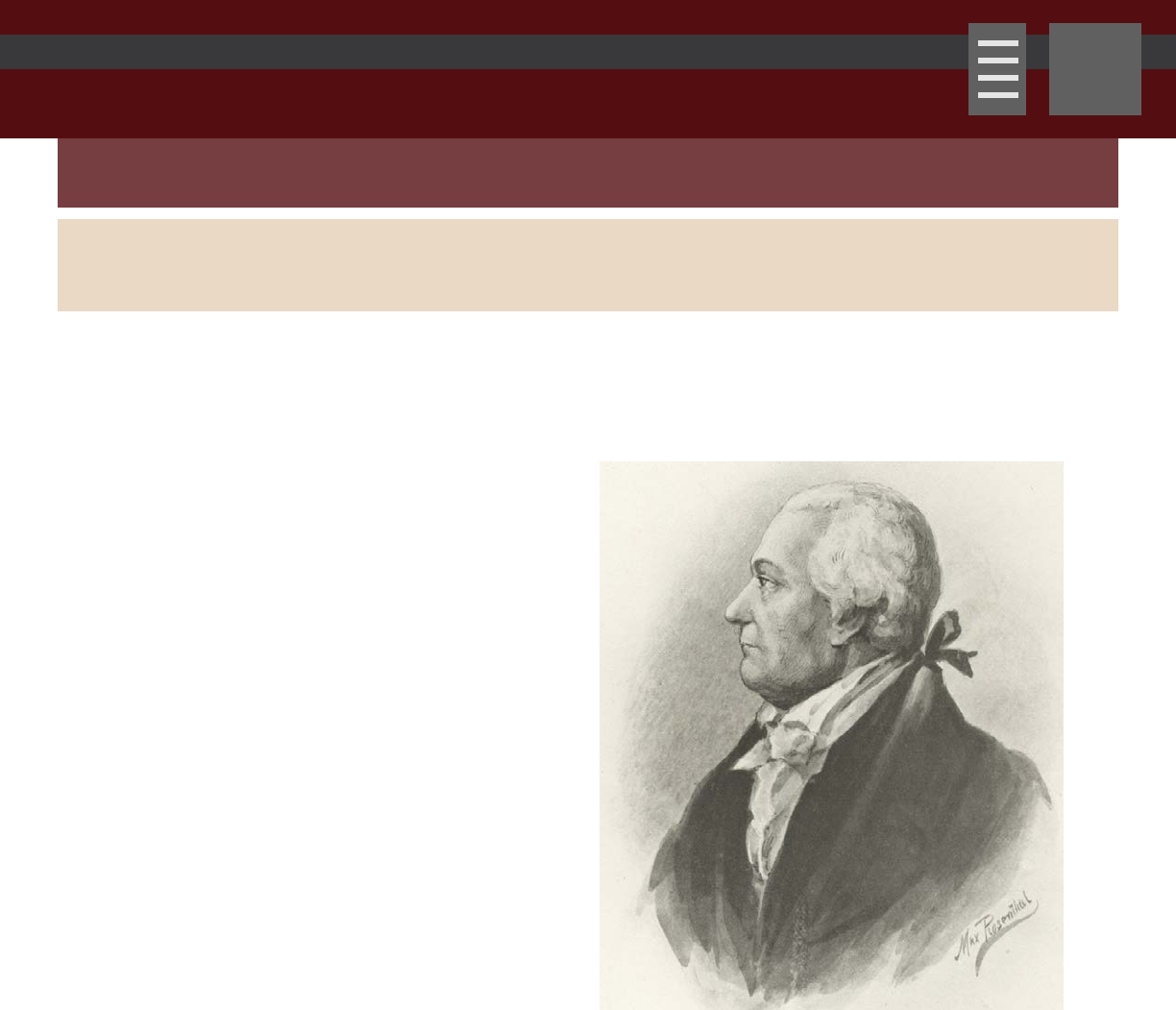

Aedanus Burke by Max Rosenthal

Print Collection, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art,

Prints and Photographs, The New York Public Library,

Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations

Burke was born in Ireland and settled in

Charleston, South Carolina, where he served

as a judge in the state. He voted against

ratification in South Carolina’s convention.

An advocate of imposing strict limits on

federal power, Burke dismissed Madison’s

amendments as, “little better than whip-

syllabub, frothy and full of wind, formed only

to please the palate….”

15

Anti-Federalist Position on Amendments

Go Inside the First Congress

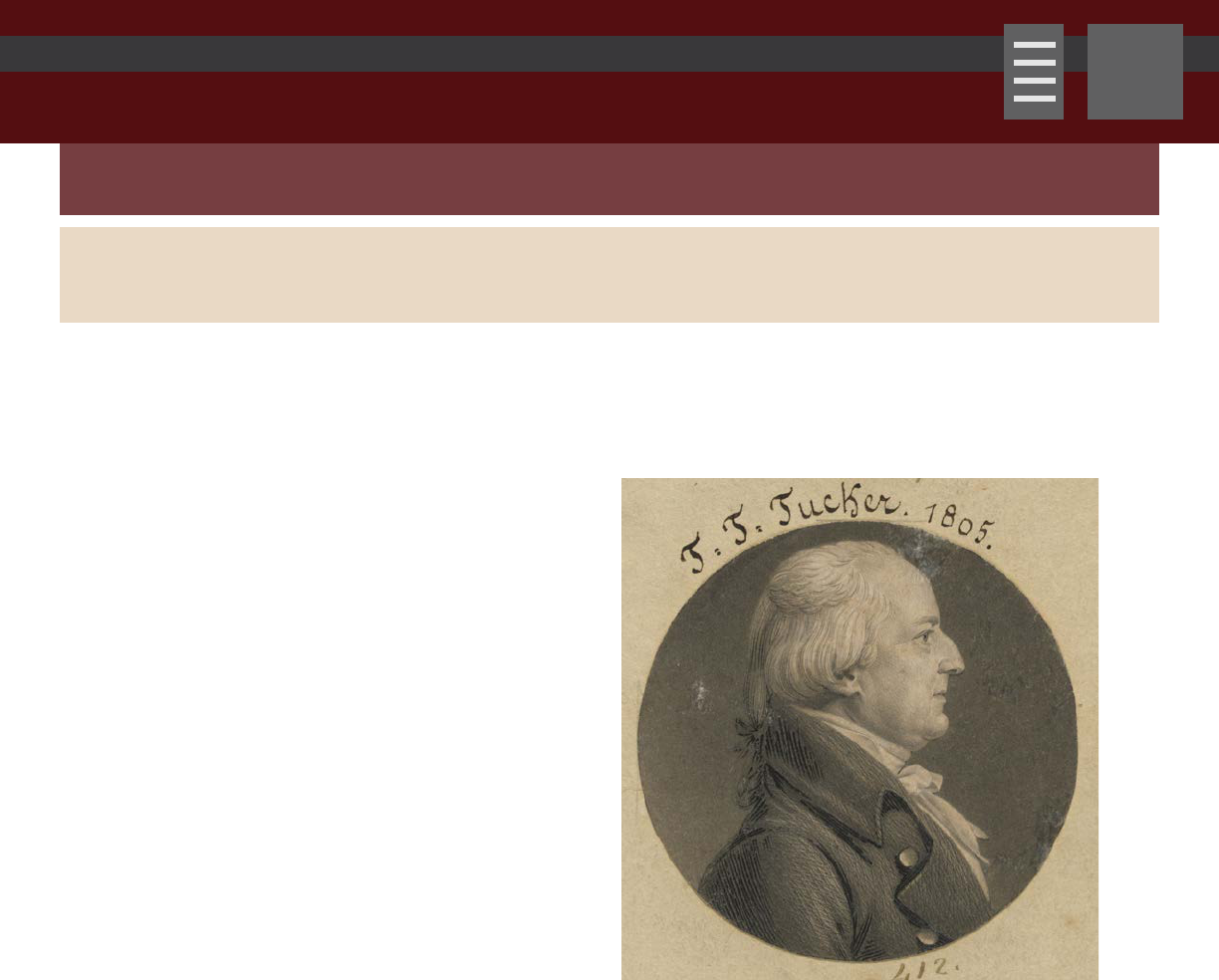

Born in Bermuda, Tucker settled in

Charleston, South Carolina. A lawyer, doctor,

and planter, he was a delegate to the state

legislature and, briefly, to the Confederation

Congress. Tudor was the proponent of

several amendments to limit federal power,

all of which were defeated in the House. He

captured the Anti-Federalist view of

Madison’s amendments when he complained

to a political ally, “You will find our

Amendments to the constitution calculated

merely to amuse, or rather to deceive.”

Thomas Tudor Tucker by Charles B.J. Févret de Saint-Mémin

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution/

Art Resource, NY

16

Anti-Federalist Position on Amendments

Go Inside the First Congress

A merchant and office holder, Gerry was

born in Marblehead, Massachusetts. A

graduate of Harvard College, he later resided

in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Gerry

attended the Continental Congress, where he

signed the Declaration of Independence, and

he was also a member of the Confederation

Congress. A delegate to the Constitutional

Convention, he refused to sign the

Constitution and actively protested its

ratification at the Massachusetts state

convention, which he attended as an

unofficial observer. He was among the most

active participants in the House debate on

amendments and insisted that “all the

amendments proposed by the respective

states” should be considered, rather than

Madison’s limited set of proposals.

Elbridge Gerry by James Barton Longacre

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution/

Art Resource, NY

17

These five questions represent the most contested issues raised in the debate over the

proposed amendments, and they best show the divide between the Federalists and the Anti-

Federalists. Many of the amendments proposed in Congress, especially those that touched

upon due process and other traditional rights, did not inspire discussion. These five triggered

the most debate, beginning with the simple question of whether the Constitution should be

amended at all.

Go Inside the First Congress

Should the Constitution be amended?

Should the House of Representatives have few or many members?

Should the people have the authority to instruct representatives?

Should the federal Bill of Rights apply to the states?

Should the federal taxation power be further limited?

18

Should the Constitution be amended?

Go Inside the First Congress

Federalist Position

“The more I consider the subject of

amendments, the more … I am convinced it

is improper .… I am against inserting a

declaration of rights in the constitution.…

If such an addition is not dangerous or

improper, it is at least unnecessary.…

Unless you except every right from the grant

of power, those omitted are inferred to be

resigned to the discretion of the

government.”

June 8, 1789

Anti-Federalist Position

“Many citizens expected that the

amendments proposed by the conventions

would be attended to by the House … and

several members conceived it to be their duty

to bring them forward.”

August 18, 1789

19

Should the House of Representatives

have few or many members?

Go Inside the First Congress

Federalist Position

“By enlarging the representation, we lessen

the chance of selecting men of the greatest

wisdom and abilities; because small district

elections may be conducted by intrigue; but

in large districts nothing but real dignity of

character can secure election.… Numerous

assemblies are supposed to be less under the

guidance of reason than smaller ones.”

August 14, 1789

Anti-Federalist Position

“Will that gentleman pretend to say we have

as much security in a few representatives as

in many? Certainly he will not. Not that I

would insist upon a burthensome

representation, but upon an adequate one …

[I am] in favor of extending the number to

two hundred …”

August 14, 1789

20

Should the people have the authority

to instruct representatives?

Go Inside the First Congress

Federalist Position

“Instructions cannot be considered as a

proper rule for a representative to form his

conduct by.… He is to consult the good of the

whole; Should instructions therefore

coincide with his ideas of the common good,

they would be unnecessary. If they were

contrary, he would be bound by every

principle of justice to disregard them.”

August 15, 1789

Anti-Federalist Position

“The power of instruction is in my opinion

essential to check an administration which

should be guilty of abuses.… To deny the

people this right is to arrogate to ourselves

more wisdom than the whole body of the

people possesses … our constituents have not

only a right to instruct, but to bind this

legislature.”

August 15, 1789

21

Should the federal Bill of Rights apply to the states?

Go Inside the First Congress

Federalist Position

“No state shall infringe the equal rights of

conscience, nor the freedom of speech, or of

the press, nor of the right of trial by jury in

criminal cases. [I] conceived this to be the

most valuable amendment on the whole list;

if there was any reason to restrain the

government of the United States from

infringing upon these essential rights, it was

equally necessary that they should be

secured against the state governments.”

August 17, 1789

Anti-Federalist Position

“It will be much better, I apprehend, to leave

the state governments to themselves, and not

to interfere with them more than we already

do, and that is thought by many to be rather

too much.”

August 17, 1789

22

Should the federal taxation power be further limited?

Federalist Position

“I hope, sir, that the experience we have had

will be sufficient to prevent Congress ever

divesting themselves of [the taxing] power …

For if this power is taken from Congress, you

divest the United States of the means of

protecting the Union, or providing for the

existence and continuation of the

government.”

August 26, 1789

Anti-Federalist Position

“That Congress shall not exercise the power

of levying direct taxes, except in cases where

any of the states shall refuse, or neglect to

comply with their requisitions.”

August 26, 1789

Go Inside the First Congress

23

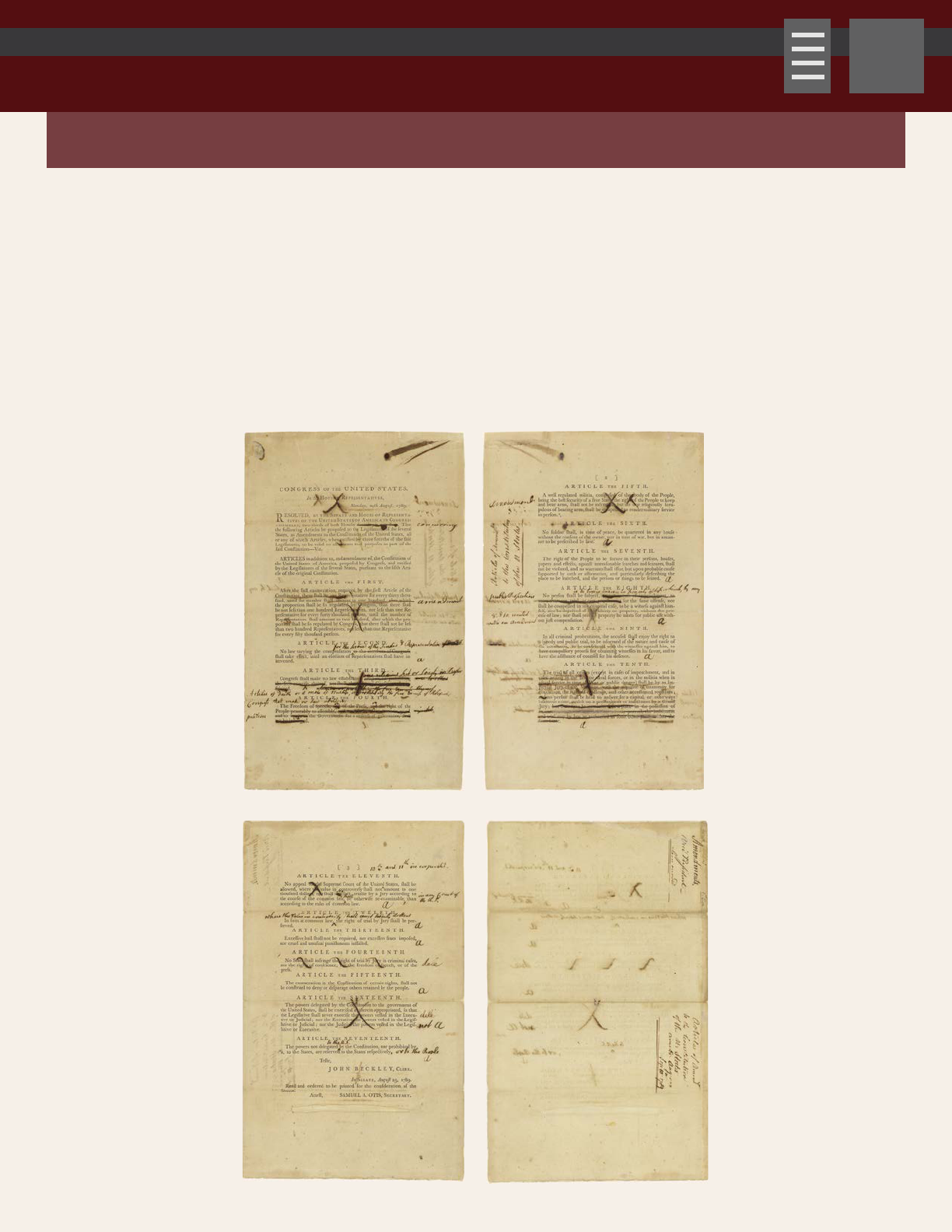

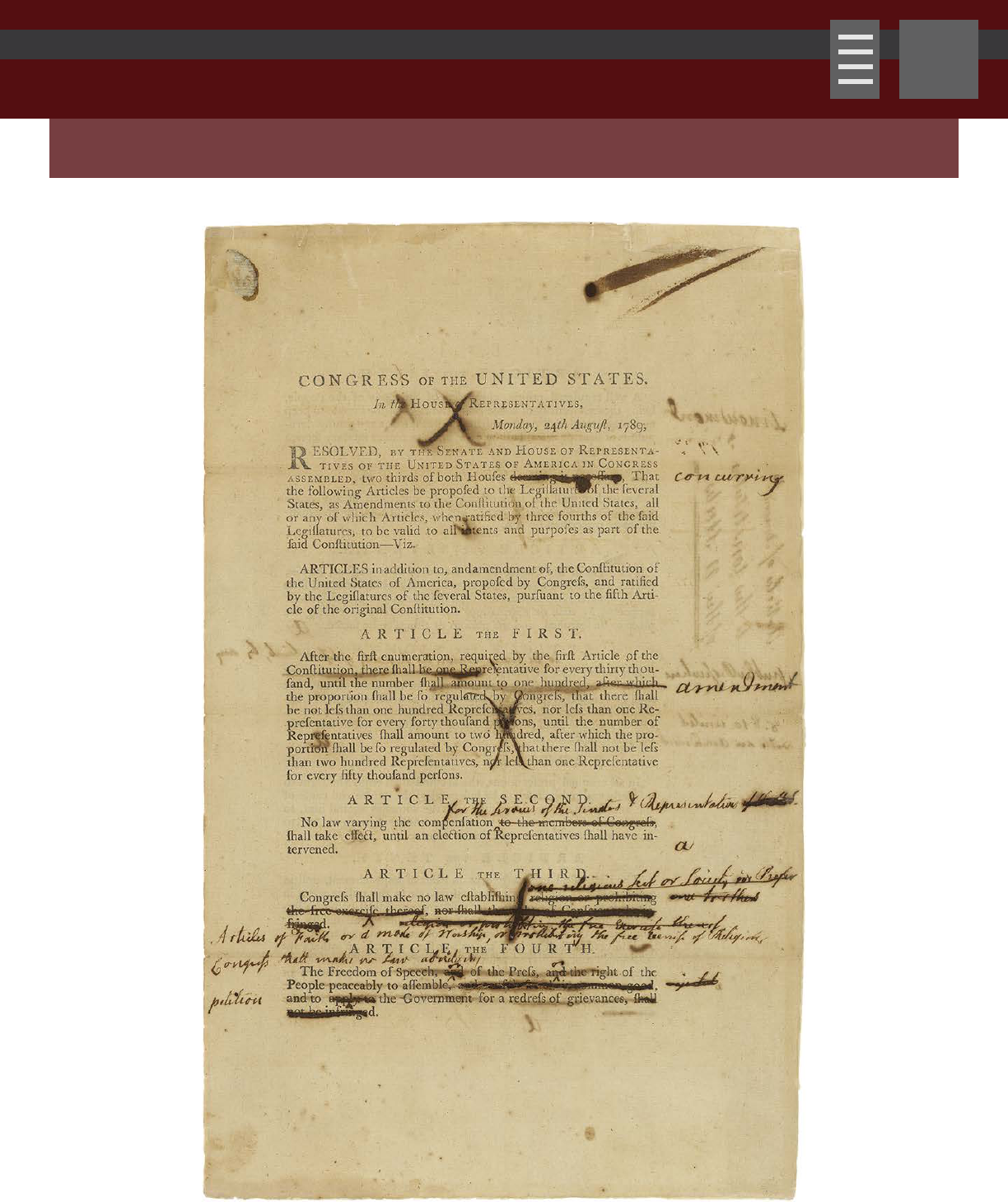

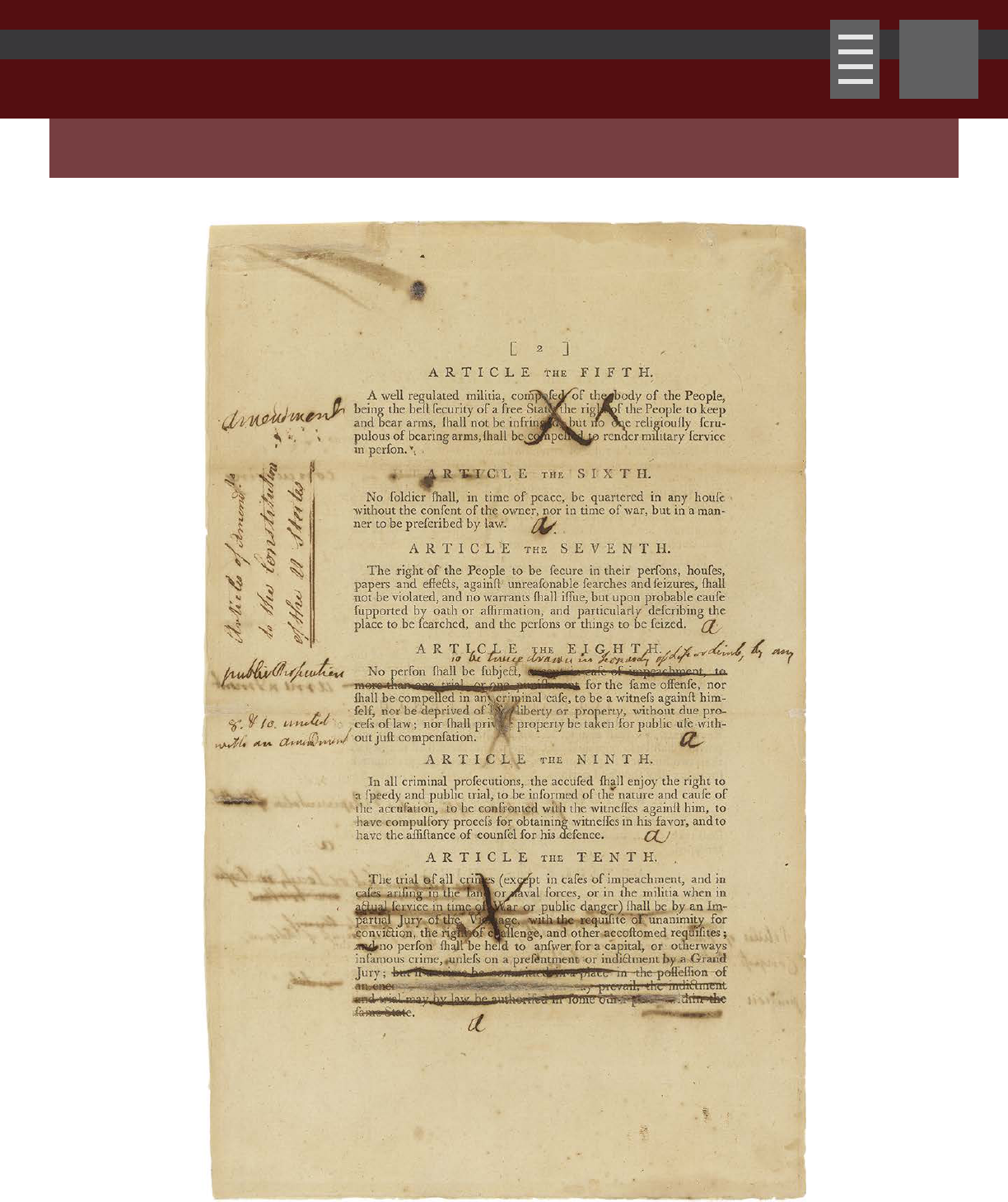

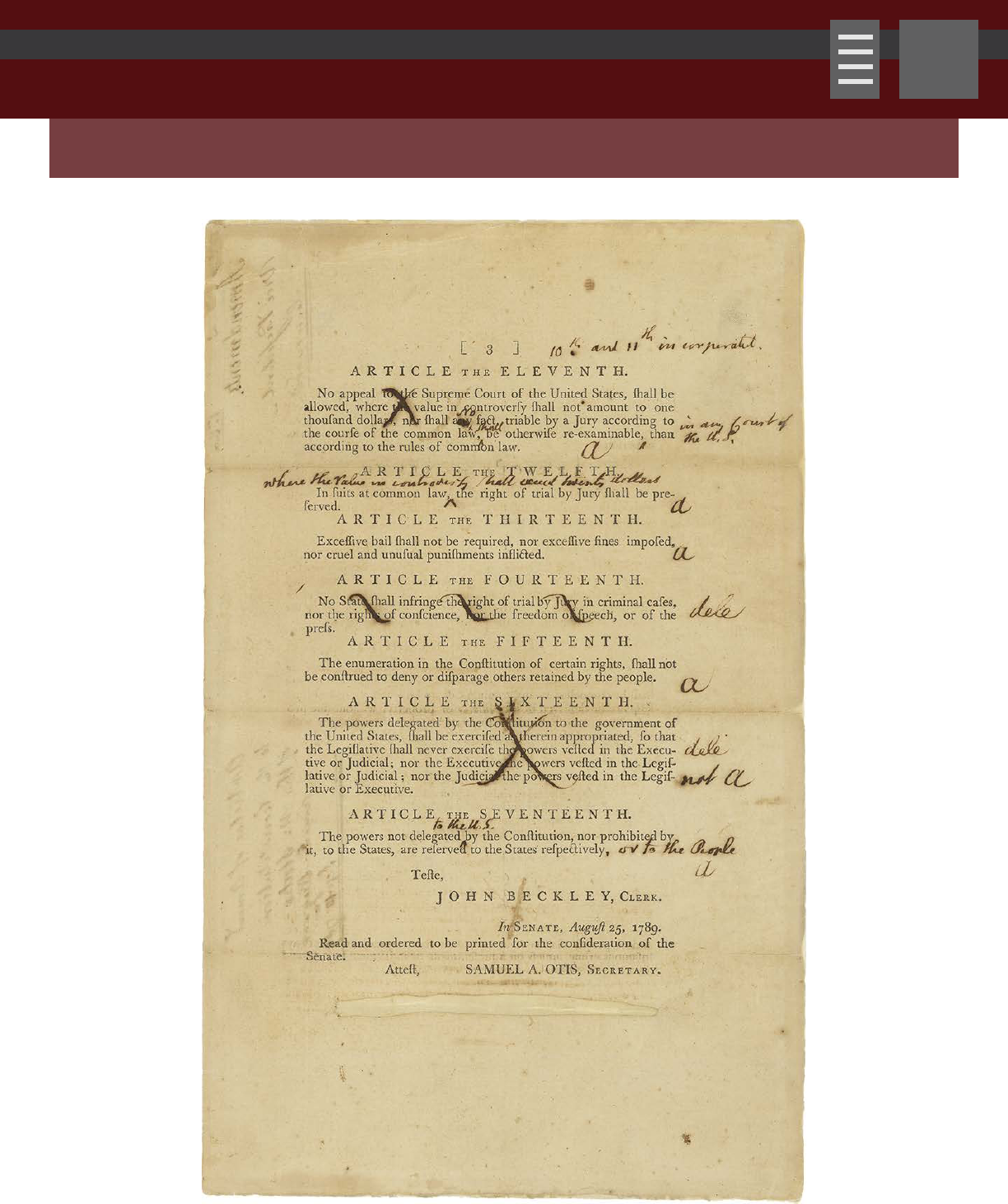

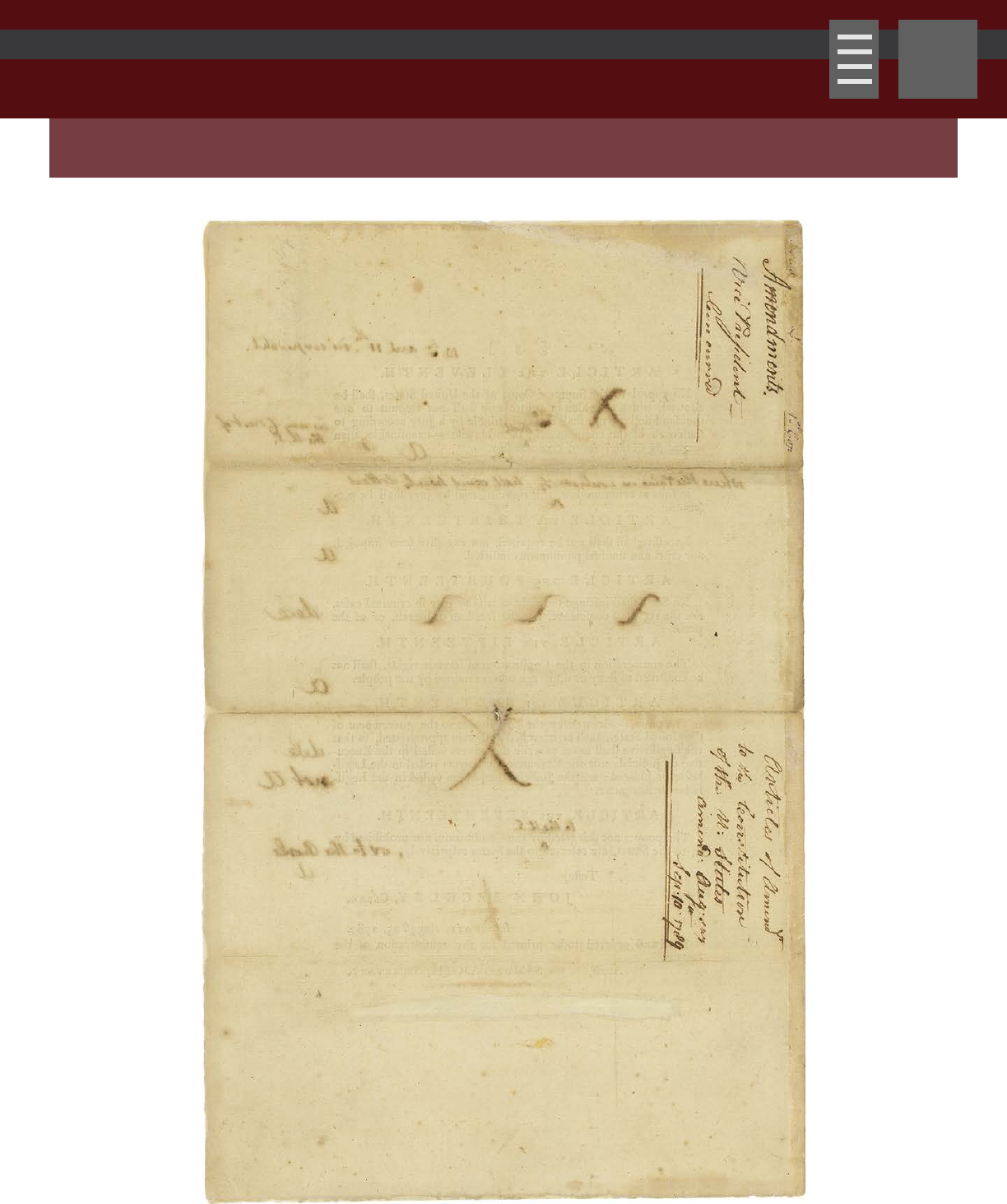

These four pages recorded on two sheets illustrate the process as seventeen House-proposed

amendments (referred to as “Articles”) were revised in the Senate. The brown ink markings,

made by the Secretary of the Senate, include cross-outs, combined amendments, and revised

language. They record the actions taken in the Senate between August 25 and September 9,

1789. After the Senate passage by a two-thirds vote, the Senate version of twelve amendments

was sent to the House for its consideration on September 14. The Bill of Rights was taking

shape, although final congressional passage would not occur until September 25.

Go Inside the First Congress

24

Senate Revisions to the House Proposed Amendments to the U.S. Constitution, 1789.

RG 46: Records of the U.S. Senate, National Archives

Go Inside the First Congress

25

Senate Revisions to the House Proposed Amendments to the U.S. Constitution, 1789.

RG 46: Records of the U.S. Senate, National Archives

Go Inside the First Congress

26

Senate Revisions to the House Proposed Amendments to the U.S. Constitution, 1789.

RG 46: Records of the U.S. Senate, National Archives

Go Inside the First Congress

27

Senate Revisions to the House Proposed Amendments to the U.S. Constitution, 1789.

RG 46: Records of the U.S. Senate, National Archives

Go Inside the First Congress

28

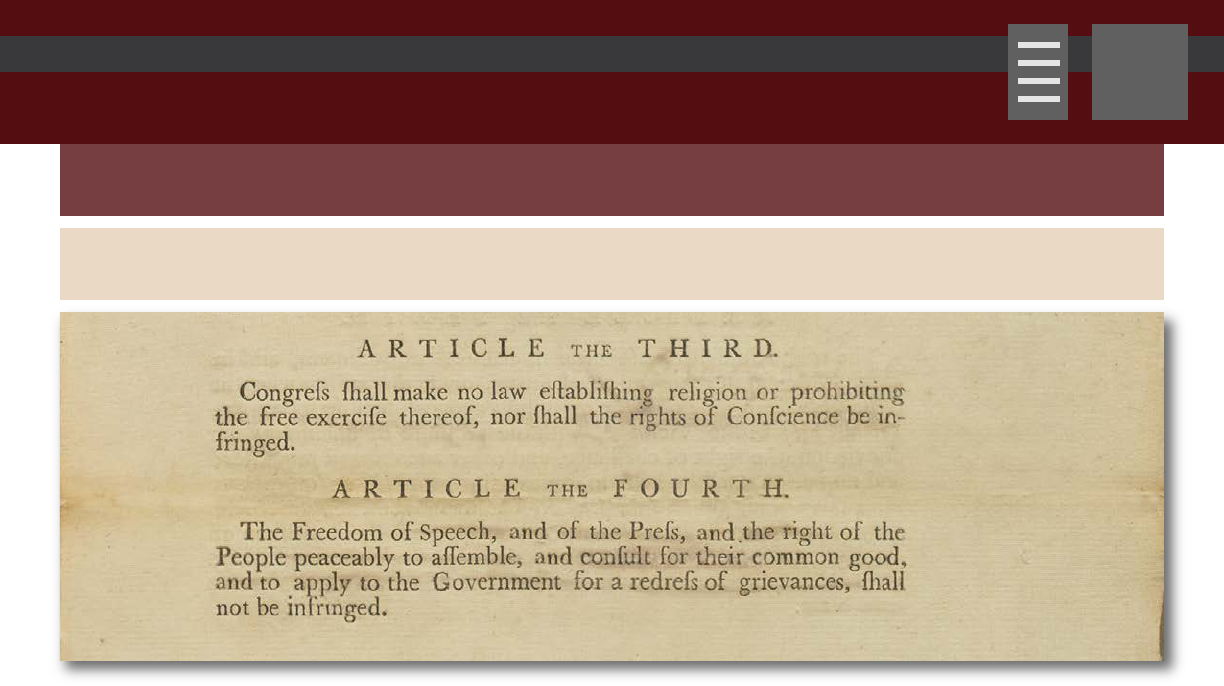

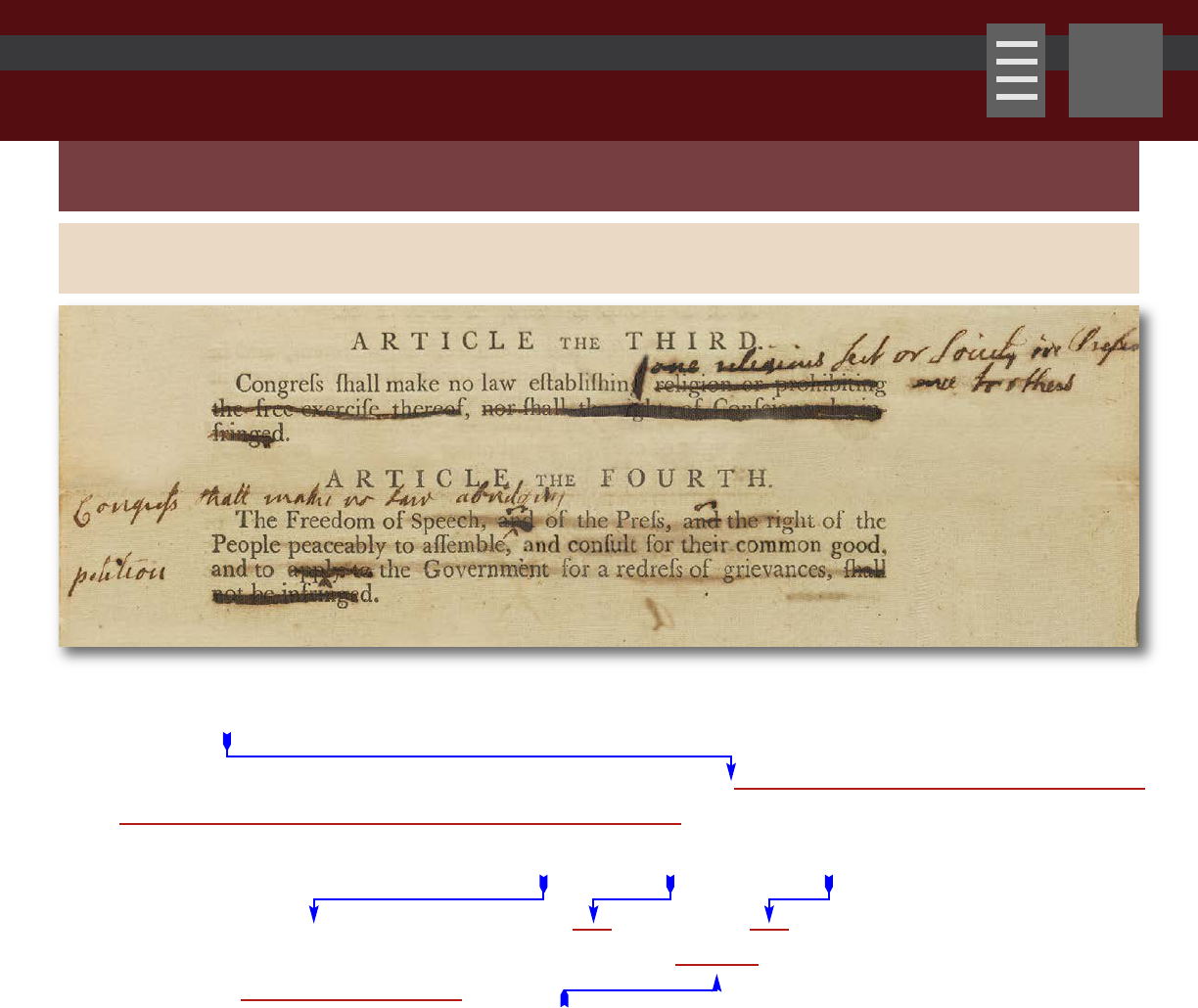

The First Amendment of the Bill of Rights changed dramatically as it moved through the

House and the Senate in 1789. The First Amendment rights as we know them today were

originally defined in two separate House amendments: Article Three on protecting religious

rights, and Article Four on the rights of speech, press, assembly, and petition.

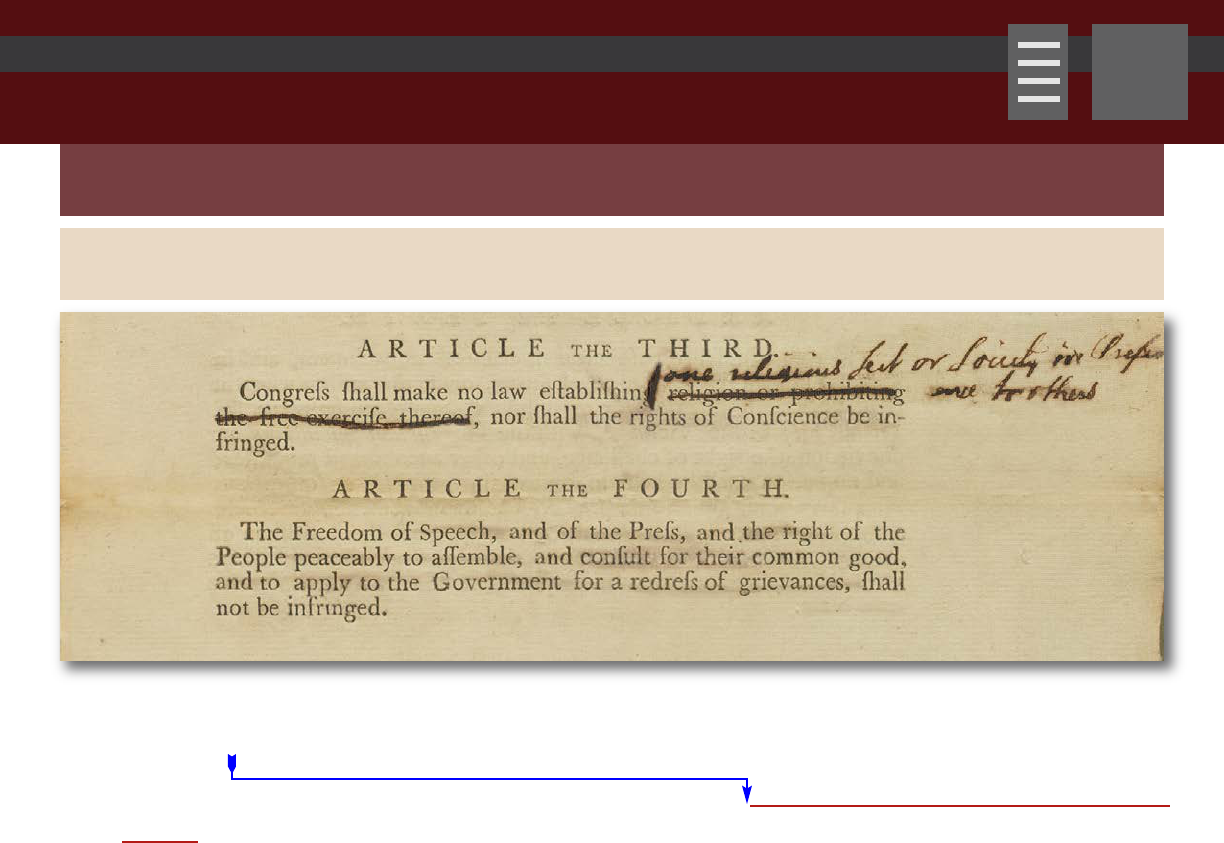

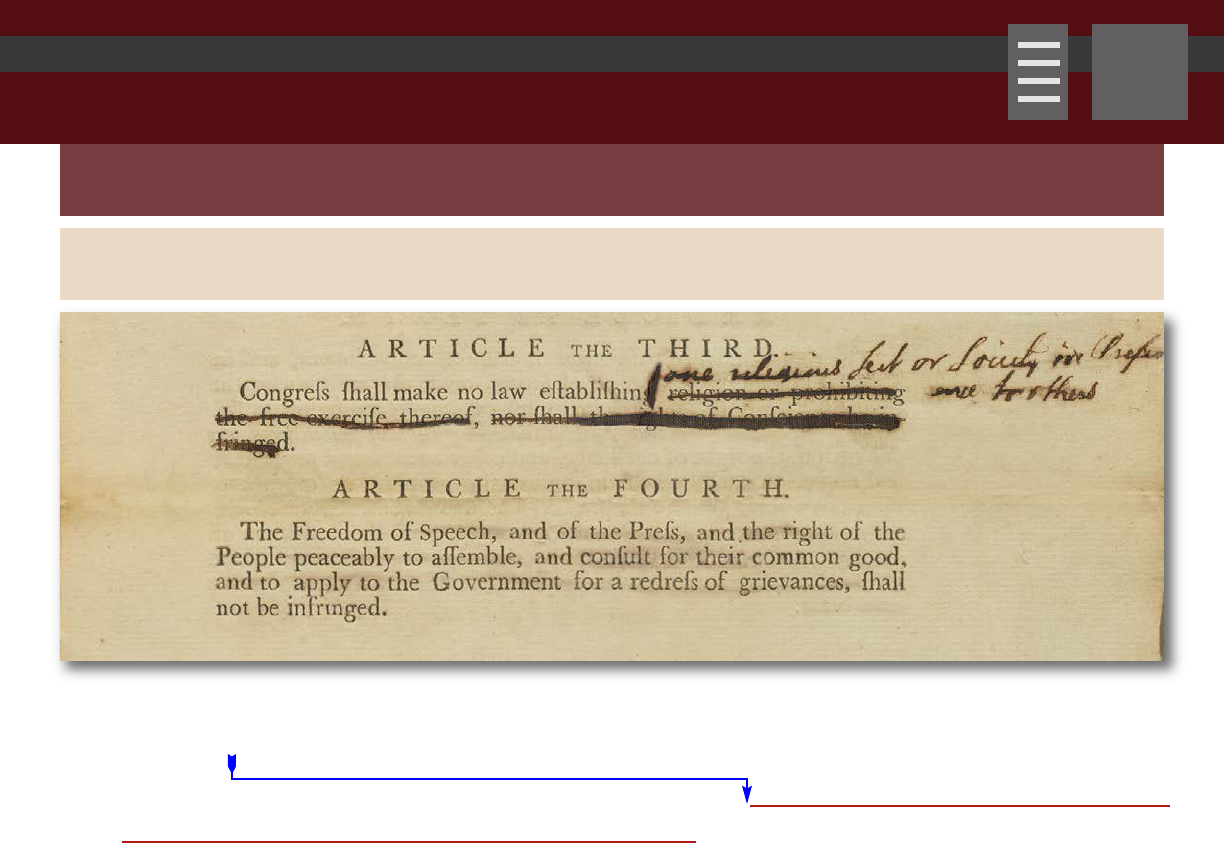

Though Senate debates were not recorded, Senate action on the amendments between August

25 and September 9 can be seen in the handwritten notations made on the printed version of

the proposed amendments passed by the House. The Senate spent a good deal of time and a

quantity of ink on Articles Three and Four, revising the language considerably. The Senate

decided to combine the two articles together, giving us a single amendment defining the

fundamental freedoms cherished by Americans in our founding era.

When the set of twelve amendments was sent to the states, the first two, Articles One

and Two, were not ratified. Article Three then rose to its preeminent place as the First

Amendment in the Bill of Rights.

This is a digital and conjectural re-creation, based on descriptions in the

Senate Legislative Journal and other sources, of step-by-step changes made

to Articles Three and Four of the proposed amendments passed by the House.

Go Inside the First Congress

29

August 24, 1789

August 24, 1789

“Article the Third. Congress shall make no law establishing religion, or prohibiting the free exercise

thereof, nor shall the rights of Conscience be infringed.

Article the Fourth. The Freedom of Speech, and of the Press, and the right of the People peaceably to

assemble, and consult for their common good, and to apply to the Government for redress of

grievances, shall not be infringed.”

Senate Revisions to the House Proposed Amendments to the U.S. Constitution, 1789.

RG 46: Records of the U.S. Senate, National Archives

Go Inside the First Congress

30

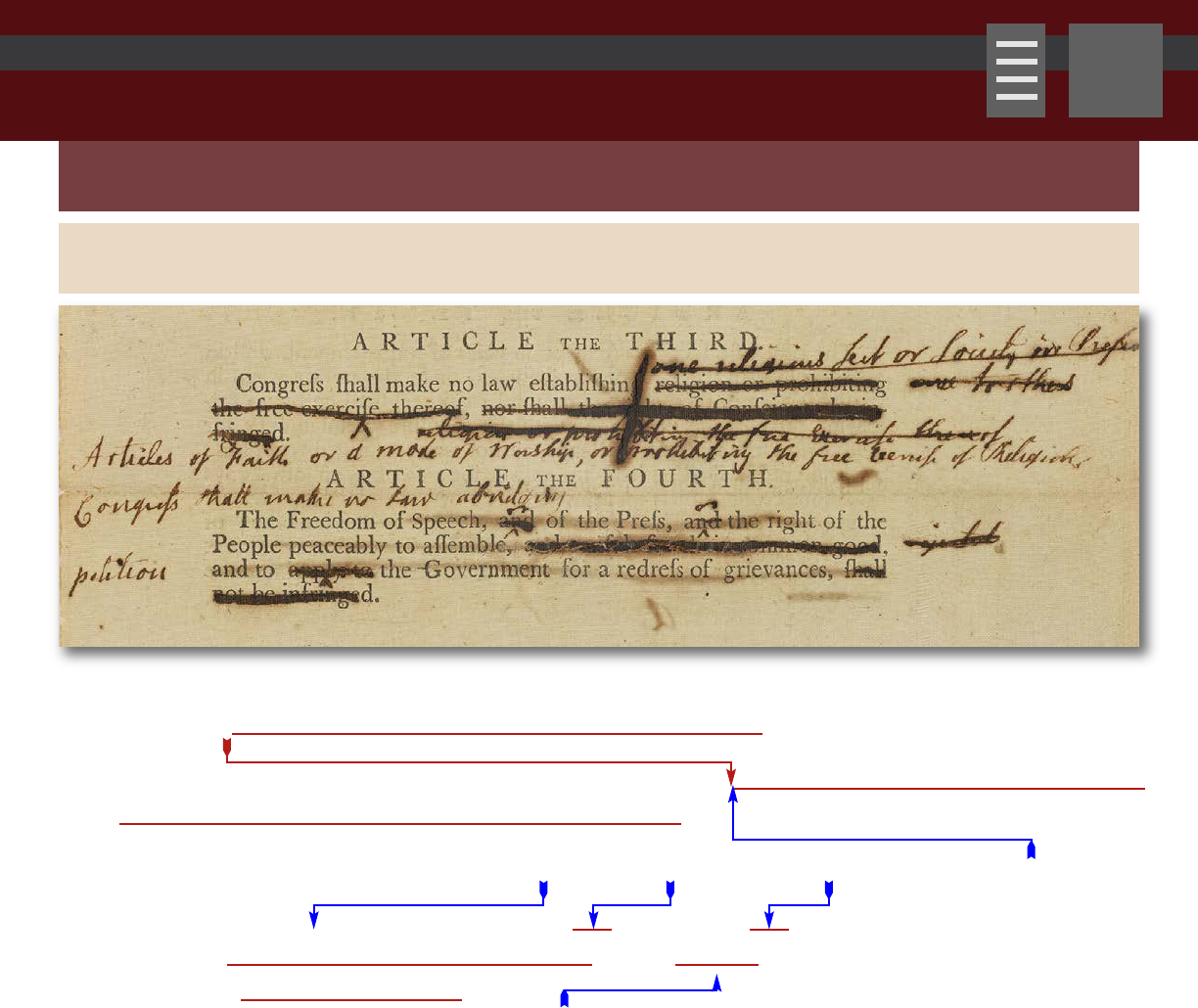

September 3, 1789

Senate Legislative Journal, September 3, 1789

Senate Revisions to the House Proposed Amendments to the U.S. Constitution, 1789.

RG 46: Records of the U.S. Senate, National Archives

“Article the Third. Congress shall make no law establishing religion, or prohibiting the free exercise

thereof, nor shall the rights of Conscience be infringed.

Article the Fourth. The Freedom of Speech, and of the Press, and the right of the People peaceably to

assemble, and consult for their common good, and to apply to the Government for redress of

grievances, shall not be infringed.”

Go Inside the First Congress

one religious Sect or Society in Preference to others

31

September 3, 1789

Senate Legislative Journal, September 3, 1789

Senate Revisions to the House Proposed Amendments to the U.S. Constitution, 1789.

RG 46: Records of the U.S. Senate, National Archives

“Article the Third. Congress shall make no law establishing religion, or prohibiting the free exercise

thereof, nor shall the rights of Conscience be infringed.

Article the Fourth. The Freedom of Speech, and of the Press, and the right of the People peaceably to

assemble, and consult for their common good, and to apply to the Government for redress of

grievances, shall not be infringed.”

Go Inside the First Congress

one religious Sect or Society in Preference to others

32

September 4, 1789

Senate Legislative Journal, September 4, 1789

Senate Revisions to the House Proposed Amendments to the U.S. Constitution, 1789.

RG 46: Records of the U.S. Senate, National Archives

“Article the Third. Congress shall make no law establishing religion, or prohibiting the free exercise

thereof, nor shall the rights of Conscience be infringed.

Article the Fourth. The Freedom of Speech, and of the Press, and the right of the People peaceably to

assemble, and consult for their common good, and to apply to the Government for redress of

grievances, shall not be infringed.”

Go Inside the First Congress

Congress shall make no law abridging or or

petition

one religious Sect or Society in Preference to others

33

September 9, 1789

Senate Legislative Journal, September 9, 1789

“Article the Third. Congress shall make no law establishing religion, or prohibiting the free exercise

thereof, nor shall the rights of Conscience be infringed.

Article the Fourth. The Freedom of Speech, and of the Press, and the right of the People peaceably to

assemble, and consult for their common good, and to apply to the Government for redress of

grievances, shall not be infringed.”

Senate Revisions to the House Proposed Amendments to the U.S. Constitution, 1789.

RG 46: Records of the U.S. Senate, National Archives

Go Inside the First Congress

Congress shall make no law abridging or or

petition

one religious Sect or Society in Preference to others

Articles of Faith or a mode of Worship, or prohibiting the free exercise of Religion

34

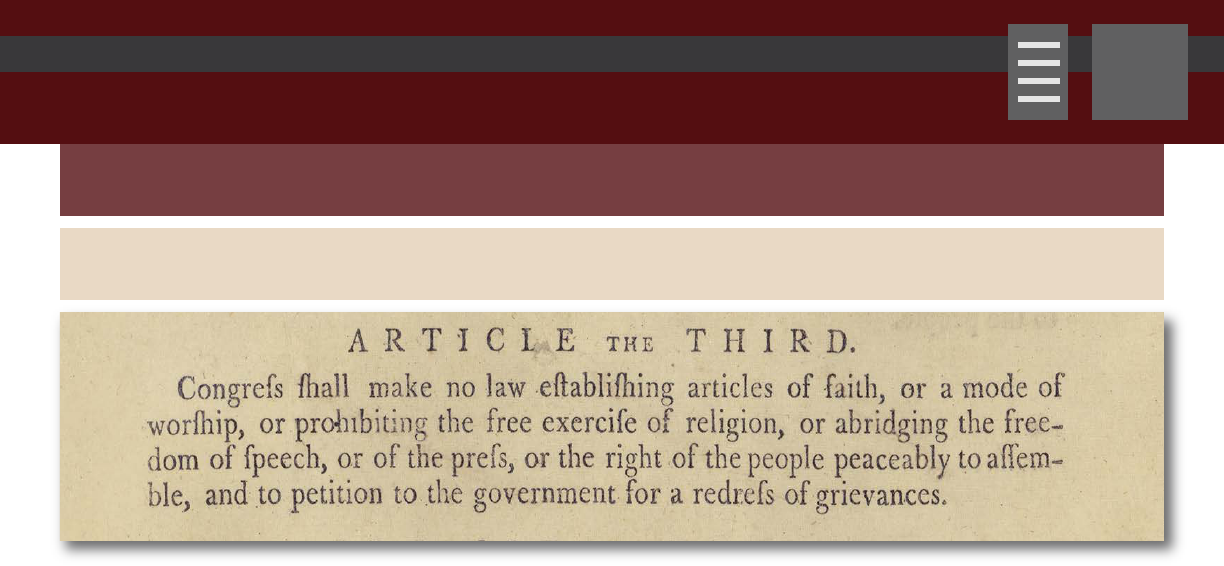

September 14, 1789

Senate Legislative Journal, September 14, 1789

“Article the Third. Congress shall make no law establishing articles of faith, or a mode of

worship, or prohibiting the free exercise of religion, or abridging the freedom of speech, or of

the press, or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition to the government

for a redress of grievances.”

Proposed Amendments to the U.S. Constitution as Passed by the Senate, 1789.

RG 46: Records of the U.S. Senate, National Archives

Go Inside the First Congress

35

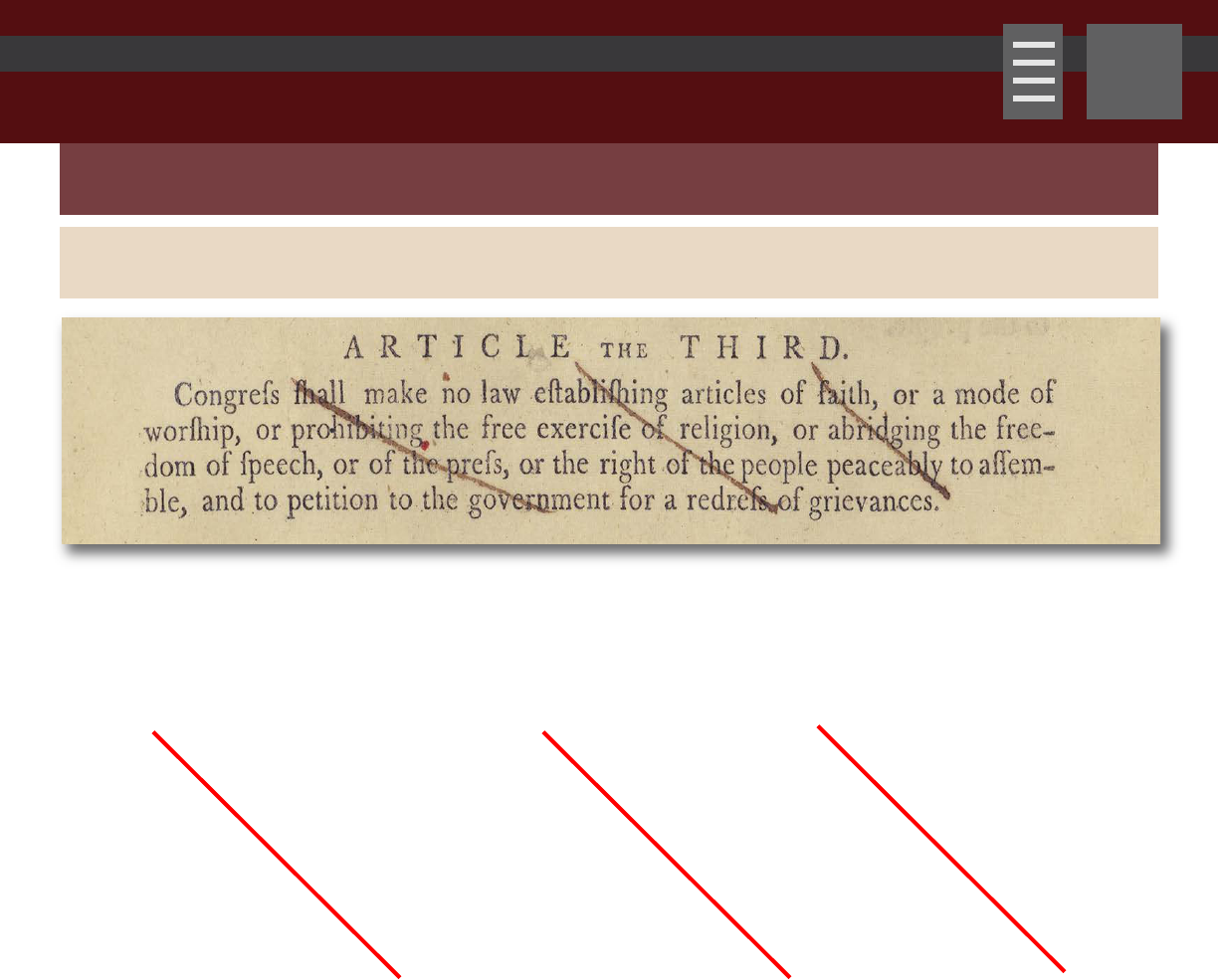

September 24, 1789

Conference Committee Report, September 24, 1789

“Article the Third. Congress shall make no law establishing articles of faith, or a mode of

worship, or prohibiting the free exercise of religion, or abridging the freedom of speech, or of

the press, or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition to the government

for a redress of grievances.”

Proposed Amendments to the U.S. Constitution as Passed by the Senate, 1789.

RG 46: Records of the U.S. Senate, National Archives

Go Inside the First Congress

36

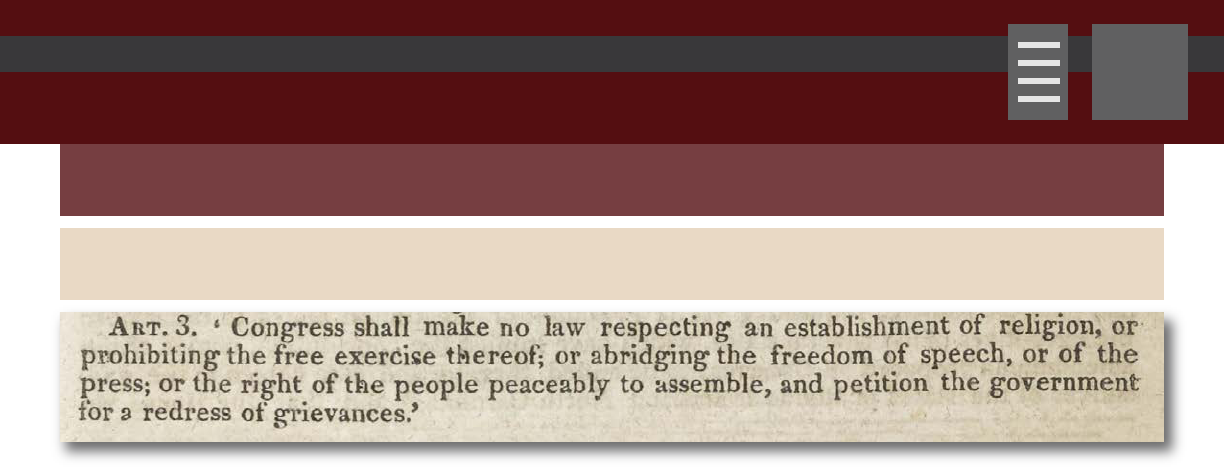

October 2, 1789

October 2, 1789

“Art. 3. Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting

the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press, or the right of

the people peaceably to assemble, and petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

Journal of the Senate of the United States of America, First Session of the First Congress, 1789–1793,

Volume 1; Washington; Gales & Seaton, 1820

Go Inside the First Congress