Hastings Journal of Crime and Punishment Hastings Journal of Crime and Punishment

Volume 1

Number 1

Winter 2020

Article 4

Winter 2020

After Abolition: Acquiescence, Backlash, and the Consequences After Abolition: Acquiescence, Backlash, and the Consequences

of Ending the Death Penalty of Ending the Death Penalty

Austin Sarat

Charlotte Blackman

Elinor Scout Boynton

Katherine Chen

Theodore Perez

Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/

hastings_journal_crime_punishment

Part of the Criminal Law Commons, and the Criminal Procedure Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Austin Sarat, Charlotte Blackman, Elinor Scout Boynton, Katherine Chen, and Theodore Perez,

After

Abolition: Acquiescence, Backlash, and the Consequences of Ending the Death Penalty

, 1 HASTINGS BUS

L.J. 33 (2020).

Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_journal_crime_punishment/vol1/iss1/4

This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository.

It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Journal of Crime and Punishment by an authorized editor of UC

Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected].

3 - Sarat_etal__HJCP1-1.docx 12/6/2019 10:10 AM

33

After Abolition: Acquiescence, Backlash,

and the Consequences of Ending the

Death Penalty

AUSTIN SARAT, CHARLOTTE BLACKMAN, ELINOR SCOUT BOYNTON,

KATHERINE CHEN, AND THEODORE PEREZ

*

Introduction

The period from 2007 to 2019 was one of the most successful in the

modern history of death penalty abolitionism.

1

In that time, ten states

abolished capital punishment. Seven did so through the legislative process,

while the other three ended the death penalty through a court decision.

2

In

one of those states in Nebraska, legislative abolition was reversed by a

referendum vote.

3

Nebraska stands out as a vivid example of what scholars

* Austin D. Sarat is the Associate Dean of Faculty and William Nelson Cromwell Professor

of Jurisprudence and Political Science at Amherst College. A leader in the scholarship of

death penalty, Professor Sarat has authored or edited over 90 books. He is the author of The

Death Penalty on the Ballot: American Democracy and the Fate of Capital Punishment

(2019), Mercy on Trial: What It Means to Stop an Execution (2005) and the co-author of

Gruesome Spectacles: Botched Executions and America’s Death Penalty (2014); Charlotte

Blackman, Amherst College ’20; Elinor Scout Boynton, Amherst College ’20; Katherine

Chen, Amherst College ’19; Theodore Perez, Amherst College ’20.

1. See generally Wayne A. Logan, Casting New Light on an Old Subject: Death

Penalty Abolitionism for a New Millennium, 100 M

ICH. L. REV. 1336, 1336-79 (2002);

Gretchen Frazee, How States Are Slowly Getting Rid of the Death Penalty, PBS

NEWS HOUR

(Mar. 13, 2019), https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/how-states-are-slowly-getting-rid-of-

the-death-penalty; S

TUART BANNER, THE DEATH PENALTY: AN AMERICAN HISTORY (Harvard

Univ. Press 2003).

2. State by State, D

EATH PENALTY INFORMATION CENTER (2019), https://deathpenalty

info.org/state-and-federal-info/state-by-state. The states ending capital punishment after

2007 were: New York, New Jersey, New Mexico, Illinois, Connecticut, Maryland,

Nebraska, Delaware, Washington, and New Hampshire.

3. A

USTIN SARAT, THE DEATH PENALTY ON THE BALLOT: AMERICAN DEMOCRACY AND

THE

FATE OF CAPITAL PUNISHMENT 86-87 (Cambridge Univ. Press 2019); see also Harry

Bruinius, In Nebraska Vote, Sign of Broader Conservative Backlash to Death Penalty,

CHRISTIAN SCIENCE MONITOR (May 28, 2015), https://www.csmonitor.com/USA/Politics/

2015/0528/In-Nebraska-vote-sign-of-broader-conservative-backlash-to-death-penalty.

3 - Sarat_etal__HJCP1-1.docx 12/6/2019 10:10 AM

34 Hastings Journal of Crime and Punishment [Vol. 1:1

have labelled “backlash”: a strong political and legal reaction in opposition

to a controversial decision.

4

The Death Penalty and Backlash

Abolitionists had good reason to fear such a reaction given what

happened several decades earlier in the wake of the United States Supreme

Court’s 1972 decision in Furman v. Georgia,

5

which declared the death

penalty unconstitutional because of the arbitrary and discriminatory manner

in which it was applied.

6

At the time, some abolitionists thought Furman

marked the end of the capital punishment in the United States.

7

As Jack

Greenberg of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored

People (NAACP) Legal Defense and Education Fund (LDF) stated that

“there will no longer be any more capital punishment in the United

States.”

8

Another commentator suggested that “[t]he Supreme Court

decision outlawing the death penalty as it is now imposed leaves the door

open for Congress or the states to write new laws that would be considered

valid. “But the door isn’t open very much.”

9

However, such predictions were quickly proven wrong.

10

Maurice

Chammah of the Marshal Project reports that “[t]he backlash to Furman

was swift and furious, as state legislatures scrambled to rewrite their laws

to satisfy the [C]ourt’s concern that the punishment was arbitrary.”

11

It was

only a matter of days after the Court’s decision before five states

4. Michael Klarman describes what he believes to be the paradigmatic example of

backlash in the reaction to Brown v. Board of Education. “Race,” Klarman argues, “became

the decisive focus of southern politics, and massive resistance its dominant theme.” See

generally Michael J. Klarman, How Brown Changed Race Relations: The Backlash Thesis,

1 J. OF AM. HIST. 81, 81-118 (1994).

5. Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238, 239-40, 256-57 (1972).

6. Daniel D. Polsby, The Death of Capital Punishment? Furman v. Georgia, 1972 S

UP.

CT. REV. 1, 1-40 (1972).

7. See generally Hugo Adam Bedau, The Case Against the Death Penalty, Capital

Punishment Project (American Civil Liberties Union, 1992); see also B

ANNER, supra note 1,

at 231-66.

8. M

ICHAEL MELTSNER, CRUEL AND UNUSUAL: THE SUPREME COURT AND CAPITAL

PUNISHMENT 215 (Quid Pro Books 2011).

9. Barry Schweid, New Laws Unlikely on Death Penalty, THE FREE LANCE-STAR (June

30, 1972), https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=pAoQAAAAIBAJ&sjid=2YoDAAAAI

BAJ&pg=3786,38609&hl=en.

10. Banner, supra note 1, at 231-66.

11. Maurice Chammah, The Odds of Overturning the Death Penalty, T

HE MARSHALL

PROJECT (Nov. 16, 2015), https://www.themarshallproject.org/2015/11/16/the-odds-of-over

turning-the-death-penalty.

3 - Sarat_etal__HJCP1-1.docx 12/6/2019 10:10 AM

Winter 2020] After Abolition 35

announced that they intended to reinstate the death penalty.

12

As renowned

death-penalty scholars Carol S. Steiker and Jordan M. Steiker note, “The

backlash in the early 1970s depended largely on the view that new energy

and attention to the death penalty could rescue it from its manifest and

manifold problems.”

13

By May 1973, thirteen states had reinstated the

death penalty and by 1976 that number increased to thirty-five.

14

The adverse reaction to Furman was also reflected in public opinion.

Three months before the decision, 42% of Americans said they were

opposed to the death penalty. Four months after Furman, opposition to the

death penalty had fallen to 32%.

15

By 1976, death penalty support reached

a twenty-five year high of 66%.

16

Backlash against Furman culminated

with the Supreme Court’s 1976 decision in Gregg v. Georgia, which held

that capital punishment did not violate the 8th and 14th amendments in all

circumstances.

17

Of course, Furman was not the only mid-twentieth century Supreme

Court decision to provoke backlash. To take another prominent example,

there is substantial scholarly literature analyzing backlash after the 1973

Roe v. Wade decision,

18

in which the Supreme Court held that the

Constitution protected abortion rights. Examining public discourse

following Roe, political science professor Vincent Vecera found that “the

Court’s ruling in Roe v. Wade played a critical role in transforming how

Americans think and talk about abortion.”

19

Other scholars claim that Roe

helped galvanize a previously dormant anti-abortion movement. Longtime

Supreme Court reporter Linda Greenhouse and Yale legal historian Reva

12. Stuart Banner, The Death Penalty’s Strange Career, 26 WILSON Q. 70, 70-82 (2002).

13. Carol S. Steiker & Jordan M. Steiker, Will the U.S. Finally End the Death Penalty?,

T

HE ATLANTIC (Mar. 15, 2019), https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2019/03/gavin-

newsoms-death-penalty-moratorium-may-stick/584977/.

14. At the time of the Furman decision, 40 states had the death penalty on the books.

That 35 of these 40 states restored capital punishment is indicative of the severity of the

post-Furman backlash. Corinna Barrett Lain, Furman Fundamentals, 82 W

ASH. L. REV. 1,

1-74 (2007).

15. PUBLIC OPINION AND CONSTITUTIONAL CONTROVERSY 112 (Nathaniel Persily et al.

eds., Oxford Univ. Press 2008).

16. Samuel R Gross, The Death Penalty, Public Opinion, and Politics in the United

States, 62 S

T. LOUIS UNIV. L.J. 763, 763-79 (2018).

17. Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S.153, 186-87 (1976). For an analysis of the period

between Furman and Gregg, see E

VAN J MANDERY, A WILD JUSTICE: THE DEATH AND

RESURRECTION OF CAPITAL PUNISHMENT IN AMERICA (W.W. Norton & Company 2015).

18. Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113, 152, 177-78 (1973).

19. Vincent Vecera, The Supreme Court and the Social Conception of Abortion, 48 L.

& SOC’Y REV. 345, 345 (2014).

3 - Sarat_etal__HJCP1-1.docx 12/6/2019 10:10 AM

36 Hastings Journal of Crime and Punishment [Vol. 1:1

Siegal note that “One effect of Roe was to mobilize a permanent

constituency for criminalizing abortion.”

20

Additionally, after Roe,

Congress passed the first limits on abortion funding,

21

and many state

legislatures enacted restrictions on abortion.

22

These actions were taken

despite general public support for Roe.

23

As the research discussed above suggests, backlash need not take the

dramatic form that it did after Furman, Roe, or when Nebraska reinstated

its death penalty. It can be registered in more nuanced ways through

institutional actions, social movement activity, public opinion, agitation by

opinion leaders and/or public discourse about an issue. Backlash can also

manifest itself in the way an issue is reframed after a decision has been

made. In a democracy, issues of political import are almost always being

framed and reframed as “various political entrepreneurs [attempt] as best

they can to affect the debate given changes in the stream of information

coming in from forces beyond their control.”

24

What this suggests is that

public backlash is often produced from the top-down by political leaders

20. Linda Greenhouse & Reva B. Siegel, Before (and After) Roe v. Wade: New

Questions about Backlash, 120 Y

ALE L.J. 2028, 2072 (2011) (quoting Benjamin Wittes,

Letting Go of Roe, T

HE ATLANTIC, 2005, at 48, 51); see Mary Ziegler, Beyond Backlash:

Legal History, Polarization, and Roe v. Wade, W

ASH. & LEE L. REV. 969, 969 (2014); Joe

Phillips & Joseph Yi, Debating Same-Sex Marriage: Lessons from Loving, Roe, and

Reynolds, 55 SOCIETY 25, 25-34 (2018). Ziegler, Phillips, and Yi contend that the Roe

decision incited an increase in abortion opponents who had been silent beforehand.

21. As Dombrink and Hillyard note, “Following Roe, a backlash in Congress led to the

first set of limitations on abortion funding and the growth of a countermovement. The

mobilization of single-issue voters and grassroots activists described by Luker and others

represented the emergence of the Christian Right in American politics as we know it today.”

J

OHN DOMBRINK & DANIEL HILLYARD, SIN NO MORE: FROM ABORTION TO STEM CELLS,

UNDERSTANDING CRIME, LAW, AND MORALITY IN AMERICA 69-70 (N.Y. Univ. Press 2007).

22. The statistics on abortion related bills introduced to Congress are as follows, 1972:

134 abortion-related bills, 4 enacted; 1973: 260 introduced, 39 enacted; 1974: 189

introduced, 19 enacted. After the decision in January 1973, we note the significant increase

in bills introduced in 1973 and 1974 when compared to 1972, before the ruling. See Judith

Blake, The Supreme Court’s Abortion Decisions and Public Opinion in the United States, 3

P

OPULATION & DEV. REV. 45, 45-62 (1977).

23. D

OMBRINK & HILLYARD, supra note 21. According to Gallup, between April 1975

and May 2018 the percentage of people who believed abortions should be illegal in all

circumstances never rose above 23%. A majority has always supported abortions in some

or all circumstances. See Abortion, G

ALLUP (2018), https://news.gallup.com/poll/1576/Abor

tion.aspx (last visited Nov. 1, 2019).

24. F

RANK R. BAUMGARTNER, SUZANNA DE BOEF & AMBER E. BOYDSTUN, THE DECLINE

OF THE DEATH PENALTY AND THE DISCOVERY OF INNOCENCE 14 (Cambridge Univ. Press

2008).

3 - Sarat_etal__HJCP1-1.docx 12/6/2019 10:10 AM

Winter 2020] After Abolition 37

who seek to leverage public reactions for political gain.

25

It involves

complex social, cultural, and political elements. In this way, debates

surrounding the death penalty resemble other complicated issues in the

United States.

The prospect of backlash, in any form, acts as a caution for politicians

who might be tempted to push for the end of America’s death penalty.

26

Politicians have lived in the shadow of the 1988 presidential campaign in

which Republicans successfully turned Democratic presidential candidate

Michael Dukakis’ abolitionism into a crushing political liability.

27

For a

long time, progressive politicians feared that opposition to capital

punishment would lead to accusations that they were soft on crime.

28

Acquiescence

But, as powerful as backlash can be, the typical response to even hotly

contested governmental decisions is acquiescence.

29

As Justice Brandeis

famously observed,

“Our government is the potent, the omnipresent teacher. For

good or for ill, it teaches the whole people by its example.”

30

25. See generally STUART A. SCHIENGOLD, THE POLITICS OF LAW AND ORDER: STREET

CRIME AND PUBLIC POLICY (Longman 1984).

26. David Dagan, Abolition and Backlash, WASH. MONTHLY (2014), https://washing

tonmonthly.com/magazine/marchaprilmay-2014/abolition-and-backlash/ (last visited Sept.

25, 2019).

27. Doug Criss, This is the 30 year old Willie Horton ad everyone is talking about

today, CNN (Nov. 1, 2018), https://www.cnn.com/2018/11/01/politics/willie-horton-ad-

1988-explainer-trnd/index.html.

28. For a recent example of such an accusation, see Kimberle Guilfoyle, Avoid the

slippery slope of ‘soft-on-crime’ policies that progressives want, THE HILL (Apr. 15, 2019),

https://thehill.com/opinion/criminal-justice/438452-avoid-the-slippery-slope-of-soft-on-crim

e-policies-that-progressives (last visited Sept. 25, 2019).

29. See generally Katerina Linos and Kimberly Twist, The Supreme Court, the Media,

and Public Opinion: Comparing Experimental and Observational Methods, 45 J.

OF LEGAL

STUD. 223, 223-54 (2016); Amir N. Licht, Social Norms and the Law: Why Peoples Obey

the Law, 4 T

HE REV. OF L. & ECON 715, 715-50 (2008); Katerina Linos & Kimberly Twist,

Controversial Supreme Court Decisions Change Public Opinion – In Part Because the

Media Mostly Report on Them Uncritically, WASH. POST (June 28, 2017), https://www.

washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2017/06/28/controversial-supreme-court-decisi

ons-change-public-opinion-in-part-because-the-media-mostly-report-on-them-uncritically/?

noredirect=on.

30. Olmstead v. United States, 277 U.S. 438, 485 (1928); Carol S. Steiker, Brandeis in

Olmstead: Our Government Is the Potent, the Omnipresent Teacher, 79 M

ISS. L.J. 145, 145-

74 (2009).

3 - Sarat_etal__HJCP1-1.docx 12/6/2019 10:10 AM

38 Hastings Journal of Crime and Punishment [Vol. 1:1

Government actions reframe and reshape the social landscape and

public perceptions. Whether immediately or after some period of

time, opinion leaders, politicians, and the public generally fall in

line. Thus, after Roe, the way people talked and thought about

abortion changed. As Vecera observes, “following the Court’s

articulation of a novel constitutional right, opinion elites should

respond by ‘constitutionalizing’ their discourse”

31

Other research suggests that public opinion ultimately follows the

same pattern as public discourse, albeit not immediately. For example, in

June 1954, directly following the ruling in Brown v Board of Education,

53% of the country approved of the Supreme Court’s decision. By 1961,

that percentage increased to 63%, and in 1994, the fortieth anniversary of

Brown, 87% of Americans approved of the Court’s decision.

32

Such a

change in public opinion occurs not just after judicial decisions, but often

occurs after the passage of legislation.

33

Some scholarly literature has also examined factors that influence the

level of acquiescence observed in a community. Professor Catherine Gross

suggests that the perceived fairness of a decision and the extent to which

relevant stake holders feel that they were involved are key to whether the

people regard it as legitimate and feel like they should go along.

34

Consequently, acquiescence is more likely when people believe that their

voices have been heard.

35

31. Vecera, supra note 19, at 370. By “opinion elites,” Vecera means people who write

opinion pieces in newspapers. Additionally, by “constitutionalizing,” he means that more of

those pieces defended the constitutionality of reproductive rights.

32. Joseph Carroll, Race and Education 50 Years After Brown v. Board of Education,

G

ALLUP (May 14, 2004), https://news.gallup.com/poll/11686/Race-Education-Years-After-

Brown-Board-Education.aspx.

33. For an analogous example, see Joseph Schuermeyer et al.’s research on marijuana

legislation. Joseph Schuermeyer et al., Temporal Trends in Marijuana Attitudes, Availability

and Use in Colorado Compared to Non-Medical Marijuana States: 2003–11, 140 D

RUG

AND

ALCOHOL DEPENDENCE 145, 145-55 (2014). See also Julianna Pacheco’s work on gay

rights which suggests an ultimate acquiescence of public opinion to whatever the law might

be. See also Julianna Pacheco, Dynamic Public Opinion and Policy Responsiveness in the

American States (Mar. 3, 2010) (unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Pennsylvania State

University) (on file with the Graduate School, Pennsylvania State University).

34. See generally Catherine Gross, Community Perspectives of Wind Energy in

Australia: The Application of a Justice and Community Fairness Framework to Increase

Social Acceptance, 35 E

NERGY POL’Y 2727, 2727-36 (2007).

35. This is a key finding of the extensive literature on procedural justice. For example,

Tyler observes, “Procedural justice judgments consistently emerge as the central judgment

shaping people's reactions to their experiences with legal authorities. As a consequence, the

3 - Sarat_etal__HJCP1-1.docx 12/6/2019 10:10 AM

Winter 2020] After Abolition 39

The Consequences of Ending Capital Punishment: Three Examples

There has been little research on reactions to post-2007 abolition of

the death penalty in American states.

36

However, studies of what happened

after various European nations abolished capital punishment show the

complexities of reactions to those decisions.

37

For example, major parties

in the United Kingdom collaborated in ending the death penalty by an act

of Parliament in 1965.

38

At the time the death penalty was abandoned,

65.5% of Britons wished to retain it. Over time, the public became even

more invested in the return of England’s death penalty. Four years after the

end of capital punishment, the percentage of people who supported

reinstatement far exceeded the percentage who supported retention in

1965.

39

Popular support for the death penalty only dipped below 50% in

2014.

40

Despite that support, no major party has made an effort to reinstate

the practice of capital punishment since the 1990s.

41

France became the last Western European nation to abolish its death

penalty in 1981. Part of the reason France was late to end capital

punishment among its European peers was the long reign of center-right

parties in the French government. When President François Mitterrand and

the left took over in 1981, a majority of the French population supported

police and courts can facilitate acceptance by engaging in strategies of process-based

regulation—treating community residents in ways that lead them to feel that the police and

courts exercise authority in fair ways.” Tom R. Tyler, Procedural Justice, Legitimacy, and

the Effective Rule of Law, 30 C

RIME AND JUST. 238, 286 (2003).

36. For exceptions see generally Aaron Scherzer, The Abolition of the Death Penalty in

New Jersey and Its Impact on Our Nation’s “Evolving Standards of Decency”, 15 M

ICH. J.

OF

RACE & L. 224, 224-65 (2009); SARAT, supra note 3.

37. Moshik Temkin, The Great Divergence: The Death Penalty in the United States

and the Failure of Abolition in Transatlantic Perspective, (Harv. Kennedy Sch., Working

Paper No. RWP15-037, 2015).

38. A

USTIN SARAT & JÜRGEN MARTSCHUKAT, IS THE DEATH PENALTY DYING?:

EUROPEAN AND AMERICAN PERSPECTIVES 193 (Cambridge Univ. Press 2011); see generally

R

OGER HOOD & CAROLYN HOYLE, THE DEATH PENALTY: A WORLDWIDE PERSPECTIVE

(Oxford Univ. Press 5th ed. 2015).

39. See generally A

NDREW HAMMEL, ENDING THE DEATH PENALTY: THE EUROPEAN

EXPERIENCE IN GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE (Palgrave Macmillan 2010).

40. Caroline Davies, Support for Death Penalty Falls in UK, Survey Finds, THE

GUARDIAN (Aug. 12, 2014) https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/aug/12/less-half-brito

nssupport-reintroduction-death-penalty-survey.

41. Additionally, it should be noted that in the Parliament, as in most state legislatures,

the representatives convened a commission and provided a detailed profile of facts on the

death penalty before voting, which we posit might be why they felt compelled to vote

against the interest of their constituents. See generally H

AMMEL, supra note 35.

3 - Sarat_etal__HJCP1-1.docx 12/6/2019 10:10 AM

40 Hastings Journal of Crime and Punishment [Vol. 1:1

capital punishment.

42

It was not until 1999 that more people opposed the

reestablishment of the death penalty than supported it.

43

Since 1993, there

have been five attempts to reinstate the death penalty in France, none of

which were successful.

44

Finally, although the death penalty has been abolished de facto in

Canada since December 1962, de jure abolition did not occur until

1976.

45

This was largely due to the Canadian public’s strong support for

capital punishment. Its supporters argued “that abolishing the death

penalty would lead to substantial increases in criminal homicides[,]” “in

more killings of police officers by criminals[,]” and maintained that

abolition would be an undemocratic act that went against popular

opinion.”

46

In 1987, Canadian Prime Minister and Conservative Party

leader Brian Mulroney fulfilled a campaign promise by introducing a

resolution in the House of Commons to restore the death penalty.

However, the measure failed by a margin of 148-127.

47

Our Research

Unlike the studies done on abolition in the United Kingdom, France,

and Canada, which focus on abolition at the national level, our research

focuses on the fate of the death penalty in American states. It concentrates

on the post-2007 period and seeks to understand what happened after

abolition of the death penalty in New Jersey, New Mexico, Illinois, and

Maryland.

48

We examined newspaper coverage of capital punishment in

42. FRANKLIN E. ZIMRING, CONTRADICTIONS OF AMERICAN CAPITAL PUNISHMENT

(Oxford Univ. Press, 2004).

43. Sophie Guerrier & Maxime Fourmaintraux, Peine de Mort: Le Long Chemin Vers

l’abolition, L

E FIGARO, http://grand-angle.lefigaro.fr/peine-de-mort-abolition-archives-hist

oire (last visited Nov. 11, 2019).

44. Id.

45. On December 11, 1962, Canada carried out its last hanging, a double hanging of

two murderers in Toronto. In 1967, Liberal Party Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson’s Bill

C-168 passed in the Canadian House of Commons, beginning a five-year moratorium on the

death penalty. In 1976, the House adopted Bill C-84, which officially abolished the death

penalty in Canada. Ezzat Fattah, Canada’s Successful Experience with the Abolition of the

Death Penalty, 25 C

ANADIAN J. OF CRIMINOLOGY 421, 423 (1983).

46. Id.

47. Ronald Sklar, Canada Trusts Parliament, Not Polls, on Death Penalty, L.A.

TIMES

(Oct. 20, 1987), https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1987-10-20-me-14606-story.html.

48. New Jersey, New Mexico, Illinois, and Maryland were selected in order to enhance

geographic diversity. We include one northeastern state, one mid-Atlantic state, one

Midwestern state and one southwestern state. Each of these states abolished the death

penalty through legislative action. Finally, none of them were among the most active death

3 - Sarat_etal__HJCP1-1.docx 12/6/2019 10:10 AM

Winter 2020] After Abolition 41

each state to see how and when the framing of arguments for and against

capital punishment changed after its abolition and whether the reframing of

arguments offers evidence of backlash.

More specifically, we look to variations in the quantity and nature of

arguments for and against abolition in the period surrounding a state’s

decision to abolish the death penalty.

49

By argument, we refer specifically

to a statement published in one of a state’s two top circulation newspapers

that contains both a declaration of a stance (pro-abolition or anti-abolition)

and a rationale to support that stance.

Categorization of Arguments for and Against Abolition

In the four states we studied, we identified thirty distinct types of

arguments used to support or oppose abolition.

Arbitrariness

Arguments about arbitrariness focus on whether the death penalty is

applied in a random way, that is, whether unexplained discrepancies exist

in its application.

Example: “The Louisiana case teaches us that capital punishment is

always pretty much a haphazard affair.”

50

Class Bias

Unlike arbitrariness, bias arguments deal primarily with the existence

of systematic partialities in death sentencing. Class bias either recognizes

or rejects the notion that death sentences are distributed unevenly across

members of different socioeconomic classes who commit the same crime.

Statements about the equal or unequal access to adequate representation

penalty states at the time they abolished the death penalty.

49. We only consider statements containing a declaration of a stance to be instances of

arguments because our aim is to examine changes in normative sentiment surrounding

abolition. Statements lacking a stance do not have this normative force, and thus serve only

as positive observations about the death penalty. For the same reason, we did not consider

statements containing a declaration of an ambiguous and/or neutral stance to be instances of

an argument. A pro-abolition stance is evidenced either by a declaration in favor of

abolition or an announcement against the death penalty. For example, both the statements “I

support abolition of the death penalty as a means to save money” and “I oppose the death

penalty because it is overly-costly” are examples of pro-abolition arguments. Similarly, an

anti-abolition stance is evidenced either by a declaration against abolition or an

announcement supporting the death penalty. For example, both the statements “abolition of

the death penalty will increase crime rates” and “retention of the death penalty keeps us

safe” are examples of anti-abolition arguments.

50. Fatally Flawed Law, S

TAR LEDGER (Sept. 5, 2003).

3 - Sarat_etal__HJCP1-1.docx 12/6/2019 10:10 AM

42 Hastings Journal of Crime and Punishment [Vol. 1:1

throughout the trial process as a result of differing levels of wealth also fall

into this category.

Example: “Almost all death-row inmates could not afford their own

attorney at trial.”

51

Constitutionality

This kind of argument makes claims about the constitutionality of

capital punishment, usually under the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition

against cruel and unusual punishment.

52

Example: “Hill argued that the method of execution in New Mexico

constitutes cruel-and-unusual punishment.”

53

Corruption

This kind of argument points to deliberate acts of particular

individuals that compromise the fairness of death penalty proceedings (e.g.,

the withholding of evidence by prosecutors).

Example: “The death penalty option has been abused so often by

ambitious prosecutors anxious to put another notch on their belts as they

prepare to run for higher office that they must be denied this punishment

option—even for the obviously guilty.”

54

Deterrence

Deterrence arguments claim one or more of the following: 1) that the

continued existence of the death penalty will prevent potential criminals

from committing crimes; 2) that the continued existence of the death

penalty will not prevent potential criminals from committing crimes; 3)

that abolishing the death penalty will lead to an increase in crime; or 4) that

abolishing the death penalty will not lead to such an increase.

Example: “I say keep the death penalty as it is a deterrent to violent

crimes and violent criminals.”

55

51. Chrysa Wikstrom, Letters to the Editor, SANTA FE NEW MEXICAN (Feb. 17, 2011),

at A11.

52. Arguments against the death penalty have also been brought under the Fourteenth

Amendment’s guarantees of due process of law and equal protection.

53. Anne Constable, Lethal-Injection Ruling Could Affect N.M., S

ANTA FE NEW

MEXICAN (Feb. 26, 2006), at C1.

54. Joe Anderson, Murder and the Death Penalty, C

HI. TRIB. (May 9, 2008), at 26.

55. Al Eisner, Letters, BALTIMORE SUN (Jan. 18, 2009), at B2.

3 - Sarat_etal__HJCP1-1.docx 12/6/2019 10:10 AM

Winter 2020] After Abolition 43

Economy

Economic arguments focus on whether the resources allocated to the

death penalty are worth its perceived benefits. Alternatively, they may make

claims about whether an alternative punishment (e.g., life imprisonment

without the possibility of parole) may be less costly or more beneficial.

Example: “O’Malley said capital cases cost three times as much to try as

other homicide cases, and described the process as ‘wasting taxpayer dollars.’”

56

Frequency

Some people argue that the penalty is so rarely enforced that it ought

to be eradicated entirely.

Example: “. . . the fact is that we have a penalty that is not

enforced.”

57

Gender Bias

This argument either recognizes or rejects the notion that death

sentences are distributed unevenly across members of different genders

who commit the same crime.

Example: “. . . [The death penalty] is biased by gender: Male

offenders are statistically more likely to be put to death than females who

commit similar crimes.”

58

Geographic Bias

Geographic bias arguments recognize or reject the notion that death

sentences are distributed unevenly across different regions for individuals

who commit the same crime.

Example: “Who gets a sentence of life and who gets death is often a

matter of . . . geography.”

59

Humanism

This argument focuses on the question of whether the practice of the

death penalty is compatible with what are perceived to be fundamental

56. Earl Kelly, O’Malley Joins NAACP in Call to End Death Penalty, THE CAPITAL

(Jan. 16, 2013).

57. John M. Shanagher, Reader Forum: Sure Punishment, S

TAR LEDGER (Nov. 30,

2007), at 22.

58. Leonard Pitts, How Can We Allow Uncertainty to Lead to Execution?, B

ALT. SUN

(Oct. 27, 2008), at 6.

59. Editorial, Abolish the Death Penalty: [Chicagoland Final Edition], C

HI. TRIB. (Mar.

25, 2007).

3 - Sarat_etal__HJCP1-1.docx 12/6/2019 10:10 AM

44 Hastings Journal of Crime and Punishment [Vol. 1:1

human rights and/or essential values of civilized society. It is often used in

reference to the inherent value of human life.

Example: “The death penalty is a clear indication of low human-rights

standards.”

60

Innocence

Arguments focusing on innocence emphasize the risk of executing

innocent people.

Example: “The execution of one innocent person is one too many, and

we simply cannot take the risk.”

61

Useful Tool for Law Enforcement

Some people support the death penalty because they think it is a useful

tool for securing confessions and guilty pleas.

Example: “Arguing last week against a repeal, Rep. Jim Sacia, R-

Pecatonica, said the mere threat of the death penalty can help police secure

a confession.”

62

Legal Theory

This argument makes a claim about whether the authority to execute

any person rests within the purview of our government and legal system,

regardless of what the written law, such as the Constitution, might say.

Example: “A few years ago, I changed my view on the death penalty

and now believe that the state has no right to kill, whether it be a

despicable, incorrigible murderer or a totally innocent unborn baby.”

63

Length of Time It Takes to Complete a Death Case

This argument focuses on the typical length of time that death penalty

cases require to reach a resolution.

Example: “‘If there is anything cruel and unusual about the death

penalty, it is the never-ending litigation with its constant ups and

downs.’”

64

60. Rebecca Procter, Letters to the Editor, SANTA FE NEW MEXICAN (Feb. 8, 2011), at

A13.

61. Opinion, Andrew Dallos, Banning Death Penalty a Wise Move, C

HI. SUN-TIMES

(Mar. 11, 2011), at 22.

62. The Senate’s Turn, C

HI. TRIB. (Jan. 11, 2011).

63. Joseph Iwanski, Reader Forum: Life Term Concerns, STAR LEDGER (Dec. 24,

2007), at 14.

64. Frederick N. Rasmussen, Dana Mark Levitz, retired Baltimore County Circuit

3 - Sarat_etal__HJCP1-1.docx 12/6/2019 10:10 AM

Winter 2020] After Abolition 45

Murder

Some supporters of abolition claim that the death penalty is a form of

murder and that by practicing the death penalty, we as a society subject

ourselves to a similar degree of moral degradation. By contrast, others

argue that the death penalty is not a form of murder and practicing the

death penalty does not implicate our society as one that sanctions murder.

Example: “Let us encourage our legislators to vote to finally abolish

state-sanctioned murder in New Jersey.”

65

Nonspecific Discrimination

This is an umbrella category for arguments regarding the question of

whether the death penalty process contains any type of discrimination.

This classification was used in instances where the argument in question

does not specify a common type of potential bias (e.g., racial, gender, class,

or geographic).

Example: “Backers of the measure said the death penalty is

discriminatory.”

66

Nonspecific Fallibility

This includes an umbrella category of arguments which focus on the

legal system’s tendency to make unspecified mistakes.

Example: “Our legal system is clearly flawed, and mistakes get

made.”

67

Nonspecific Lack of Justification

These pro-abolition arguments assert that no reason in favor of the

death penalty is strong enough to justify the practice.

Example: “So where’s the logic in state-sanctioned executions? There

isn’t any.”

68

Court judge, dies, BALT. SUN (Jan. 20, 2018), https://www.baltimoresun.com/obituaries/bs-

md-ob-judge-dana-levitz-20180118-story.html.

65. Nancy Taiani, Reader Forum: Many Victims, S

TAR LEDGER (Nov. 30, 2007), at 22.

66. Dan Boyd, A Death Penalty’s Final Hour? - Approval Sends Measure to

Richardson for Decision, A

LBUQUERQUE J. (Mar. 14, 2009).

67. Leah Popp and Barak Wolff, Letters to the Editor, S

ANTA FE NEW MEXICAN (Feb.

10, 2009), at A.

68. Leonard Pitts, Choosing Conscience Over Emotion in Illinois, S

TAR LEDGER (Jan.

17, 2003), at 19.

3 - Sarat_etal__HJCP1-1.docx 12/6/2019 10:10 AM

46 Hastings Journal of Crime and Punishment [Vol. 1:1

Nonspecific Public Protection

This is an umbrella category for arguments concerning the capacity of

the death penalty to protect the public from crime. In general, this

argument does not specify whether the cause for concern are potential

criminals (‘deterrence’) or already-convicted criminals (‘repeat offense’).

Example: “And if the death penalty, when appropriately applied, can

save even one innocent victim, it will have been worth it.”

69

Procedural Botch (in Execution)

This argument focuses on the risk of a failed or unexpectedly

prolonged execution.

Example: “Foes of capital punishment seized on the execution to

argue that the death penalty is cruel and unusual punishment, just as they

did after two inmates’ heads caught fire in Florida’s electric chair in 1990

and 1997 and a condemned man suffered a severe nosebleed in 2000.”

70

Proportionality

Proportionality asserts that punishment is justified when it balances

the gravity of crime. Pro-abolition arguments suggest that the death

penalty is too harsh in relation to any crime, whereas anti-abolition

arguments claim the death penalty is the only appropriate punishment for

certain heinous crimes.

Example: “We have no problem with imposing the death penalty on

those unquestionably guilty of heinous crimes.”

71

Public Opinion

Arguments appealing to public opinion assert that the death penalty

ought to be retained or abolished by highlighting public support for either

of those alternatives.

Example: “. . . I am sure that most Americans are in favor of justice.”

72

69. Marilyn Flax and Sharon Hazard-Johnson, Your Views, NEW JERSEY RECORD (May

8, 2007), at L6.

70. Critics Say Murderer’s Execution Was Botched; Florida Inmate Took 34 Minutes to

Die, THE RECORD (Dec. 15, 2006), at A4.

71. Martin O’Malley, Our Say: Maryland Needs to End Its Death Penalty Impasse, THE

CAPITAL (Jan. 13, 2013) https://www.capitalgazette.com/cg2-arc-df3834c6-fced-5ae9-a426-

ad2c57f67f9c-20130113-story.html.

72. Rev. Tom McLaughlin, Reader Forum: Victims’ Pain, S

TAR LEDGER (Dec. 24,

2007), at 14.

3 - Sarat_etal__HJCP1-1.docx 12/6/2019 10:10 AM

Winter 2020] After Abolition 47

Racial Bias

A racial bias argument either recognizes or rejects the claim that death

sentences are distributed unevenly across members of different races who

commit the same crime.

Example: “Critics of the death penalty maintain that it is still applied

in a racially discriminatory way False”

73

Redemption

Redemption arguments focus on the possibility that individuals, and

especially convicted criminals, can change for the better.

Example: “What purpose does he serve by continuing to breathe?

What do you do with trash? Dispose of it. You do not keep it

around to see if it improves. It doesn’t. It has served its purpose and

needs to be discarded.”

74

Religion

The religion rationale is an acknowledgement of the death penalty as

either an acceptable or unacceptable institutional practice within some

particular religious community, most often in the context of Christianity.

Example: “The Bible tells us ‘Thou shalt not kill,’ which means no

one.”

75

Repeat Offense

The repeat offense rationale states either that the continued existence

of the death penalty will prevent already-convicted criminals from

committing another crime, or that it will not impact recidivism rates.

Another repeat offense rationale asserts that abolishing the death penalty

will encourage already-convicted criminals to commit another crime, while

the inverse emphasizes that abolition will not encourage those already-

convicted from committing another crime.

Example: “Opponents of repeal were concerned that without a death

penalty, prison guards and police officers would be more vulnerable to

harm from prisoners and others.”

76

73. James Oliphant, Recent Decisions Have Narrowed Use of Death Penalty, CHI. TRIB.

(Apr. 17, 2008), at 16.

74. Howard Shaw, Your Views, N

EW JERSEY RECORD (Dec. 14, 2011), at A18.

75. Stella Foster, Stella’s Spotlight: Death Revisited, C

HI. SUN-TIMES (Jan. 20, 2011), at

21.

76. Deborah Baker, Archbishop: Keep Ban on Death Penalty - Sheehan Says

Reinstatement Would Be a ‘Step Backward, A

LBUQUERQUE J. (Jan. 20, 2011) https://ww

3 - Sarat_etal__HJCP1-1.docx 12/6/2019 10:10 AM

48 Hastings Journal of Crime and Punishment [Vol. 1:1

Slippery Slope

Supporters of capital punishment sometimes argue that abolishing the

death penalty would pave the way for changing ultimate punishments to the

point where even the most severe sentences would be too lenient.

Example: “How long will it take before some group, with the ACLU’s

eager help, decides that life in prison is almost as cruel as the death

penalty? These people will make the argument that after 30 or 40 years,

murderers are rehabilitated and it would be ‘cruel and unusual punishment’

to keep them locked up. We will have murderers in their 50s and 60s out

looking for the people who testified against them.”

77

Standards of Decency

This argument makes a claim about whether the death penalty is

compatible with modern standards of decency in civilized societies.

Example: “‘Civilized people don’t kill,’ said Barbara de Weever of

Santa Fe after her audience with Richardson on Monday.”

78

Victims’ Families

Thinking about the families of murder victims plays a role in the way

some people make arguments for and against abolition.

Example: “I think that when the defendant is executed, the family

would feel justice is being served.”

79

Other

This catch-all category includes all arguments not included among the

29 distinct categories defined above.

Example: “Sister Helen said state-trained executioners have confided

to her the psychological harm done to them by their participation in

executions.”

80

Abolition in Action: The Stories of Four States

In this section, we track the role that the arguments listed above

played in debates about and reactions to abolition in New Jersey, New

w.abqjournal.com/news/state/202325564746newsstate01-20-11.htm.

77. John F. Jernigan, Reader Forum: Killers’ Blood Lust, S

TAR LEDGER (Jan. 17, 2007),

at 12.

78. Dan Boyd, Thinking It Over, A

LBUQUERQUE J. (Mar. 17, 2009).

79. Ernest Tapia, Letters to the Editor, S

ANTA FE NEW MEXICAN (Mar. 8, 2009), at B.

80. Taiani, supra note 65.

3 - Sarat_etal__HJCP1-1.docx 12/6/2019 10:10 AM

Winter 2020] After Abolition 49

Mexico, Illinois, and Maryland. Below we present brief overviews of each

state’s abolition story and then examine the frequency and nature of

arguments about capital punishment before and after abolition.

New Jersey

Of the four states we studied, New Jersey was the first to repeal its

death penalty which it did at the end of 2007.

81

Indeed, it was the first state

in the country to do so in the preceding forty-two years.

82

While the state

reinstated capital punishment in 1982, six years after Gregg v. Georgia,

New Jersey did not executed anyone after 1963.

83

The first rumblings of a serious death penalty repeal effort during the

ten-year period of our study began in early 2003 in response to Illinois

Governor George Ryan’s commutation of 167 death row inmates’

sentences.

84

Governor Ryan’s sweeping act was greeted with great

enthusiasm by New Jersey abolitionists.

85

Their activity resulted in the

passage of a bipartisan bill calling for a study of the death penalty in

2003.

86

That legislation, however, was vetoed by then-governor James

McGreevey.

87

One year after Governor McGreevey’s veto, a death row inmate

named Robert Marshall was granted a new trial when a judge ruled that his

original trial had been unfair.

88

Abolitionists championed the Marshall

81. Henry Weinstein, N.J. on Verge of Repealing Death Penalty, L.A. TIMES (Dec.

14, 2007), https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2007-dec-14-na-abolish14-story.html;

RAYMOND J. LESNIAK, THE ROAD TO ABOLITION: HOW NEW JERSEY ABOLISHED THE DEATH

PENALTY 65 (Kean Univ. Press 2008).

82. Elise Young, Slaying of N.J. Family Draws Calls to Bring Back Death Penalty,

B

LOOMBERG (Dec. 5, 2018), https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-12-05/slaying-

of-n-j-family-draws-calls-to-bring-back-death-penalty.

83. New Jersey Abolishes Death Penalty, NPR (Dec. 17, 2007), https://www.npr.org/

templates/story/story.php?storyId=17314934.

84. L

ESNIAK, supra note 81, at 12.

85. Id

87. Barbara Fitzgerald, Rethinking the Death Penalty, N.Y.

TIMES (Dec. 14, 2003),

https://www.nytimes.com/2003/12/14/nyregion/rethinking-the-death-penalty.html; see also

L

ARRY W. KOCH, COLIN WARK & JOHN F. GALLIHER, THE DEATH OF THE AMERICAN DEATH

PENALTY: STATES STILL LEADING THE WAY 43 (Northeastern Univ. Press 2012).

87. Barbara Fitzgerald, Rethinking the Death Penalty, N.Y.

TIMES (Dec. 14, 2003),

https://www.nytimes.com/2003/12/14/nyregion/rethinking-the-death-penalty.html; see also

LARRY W. KOCH, COLIN WARK & JOHN F. GALLIHER, THE DEATH OF THE AMERICAN DEATH

PENALTY: STATES STILL LEADING THE WAY 43 (Northeastern Univ. Press 2012).

88. Leigh B. Bienen, Not Wiser after 35 Years of Contemplating the Death Penalty, 42

S

TUD. IN L., POL. & SOC’Y 91, 101 (2008).

3 - Sarat_etal__HJCP1-1.docx 12/6/2019 10:10 AM

50 Hastings Journal of Crime and Punishment [Vol. 1:1

case as a prime example of errors pervasive throughout the death penalty

system. A few months later, Ocean County Prosecutor Thomas Kelaher

announced that he would no longer pursue capital punishment in

Marshall’s case, which further fanned the flames of abolition sentiment.

89

Death penalty opponents argued that if a killer as “particularly depraved”

and “cold-blooded” as Marshall could not be executed, then no one

deserved the death penalty.

90

Pro-abolition sentiment gained further momentum in 2005

91

when, in

December of that year, California executed Stanley Tookie Williams.

92

His

story was featured prominently in The Star Ledger, New Jersey’s largest

circulation newspaper. New Jersey abolitionists frequently invoked the

Williams execution and the allegations of racism that surrounded it to

punctuate their own arguments against the death penalty.

93

While the controversies surrounding the Marshall and Williams cases

continued, a group called New Jerseyans for Alternatives to the Death

Penalty released a report detailing what it found to be the exorbitant costs

of maintaining the death penalty

94

and proposed a bill to replace it with life

in prison without the possibility of parole.

95

However, allies in the

legislature wanted to wait until known death penalty opponent Governor-

elect Jon Corzine took office.

96

Meanwhile, Catholic organizations joined New Jersey’s anti-death

penalty activists and pushed both for the creation of a death penalty study

commission and a moratorium on executions.

97

Their support was critical

89. Id.

90. Robert Schwaneberg, Case Shows Cracks in Death Penalty System, STAR LEDGER

(May 14, 2006), at 35.

91. See id.

92. Crips Co-Founder Williams Put to Death, NPR (Dec. 13, 2005), https://www.n

pr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5050214.

93. See generally Steve Lopez, A Killer Isn’t Alone in His Barbarism - Tookie’s No

Martyr but His Execution Can’t Be Defended, S

TAR LEDGER (Dec. 15, 2005), at 19; John M.

Crisp, Rethinking the Death Penalty, T

HE RECORD (Feb. 16, 2006), at L11.

94. Mary E. Forsberg, Money For Nothing? The Financial Cost of New Jersey’s Death

Penalty, N

EW JERSEYANS FOR ALTERNATIVES TO THE DEATH PENALTY (Nov. 2005),

http://www.njadp.org/forms/cost/MoneyforNothingNovember18.html (last visited Nov. 1,

2019).

95. Jessica S. Henry, New Jersey’s Road to Abolition, 29 T

HE JUST. SYS. J. 408, 408-22

(2007).

96. Lesniak, supra note 81, at 61.

97. Religious groups such as the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops proved to be an

especially powerful force behind the death penalty repeal effort. Bishops were looking to

persuade Catholic politicians to vote in accordance with their professed faith, which

3 - Sarat_etal__HJCP1-1.docx 12/6/2019 10:10 AM

Winter 2020] After Abolition 51

in a state where 40% of the residents were Catholics. New Jerseyans for

Alternatives to the Death Penalty supported this call for a study and a

moratorium; Sister Helen Prejean, the nationally known opponent of capital

punishment, visited New Jersey to lobby legislators.

98

The legislature

responded favorably to the proposal for a commission, and in 2005 a thirteen

member body was created to study the death penalty’s costs and procedures.

99

In January 2007, the New Jersey Death Penalty Study Commission

recommended the elimination of capital punishment by an 11-1 vote, a

suggestion that Governor Corzine strongly supported.

100

The Commission

made eight separate findings of fact: (1) the death penalty does not serve a

legitimate penological interest; (2) the costs of the death penalty are greater

than life without possibility of parole; (3) the death penalty is inconsistent

with evolving standards of decency; (4) there is no invidious racial bias in

the application of the death penalty in New Jersey; (5) abolition will

eliminate the risk of disproportionality in sentencing; (6) the penological

gain in executing a small number of guilty persons is not sufficiently

compelling to justify the risk of an irreversible mistake; (7) life without

possibility of parole ensures public safety and addresses other legitimate

penological interests, including the interests of the families of murder

victims; and (8) sufficient funds should be dedicated to ensure adequate

services and advocacy for the families of murder victims.

101

Following the commission’s report, legislation to end the death

penalty began to move through the House and Senate. In May 2007, the

Senate Judiciary Committee approved a bill sponsored by Senator

Raymond Lesniak calling for replacing the death penalty with life

imprisonment without the possibility of parole.

102

After Senator Lesniak’s

bill passed both houses and easily earned Governor Corzine’s signature,

New Jersey became the first state to eliminate capital punishment through

legislative means in the twenty-first century.

103

emphasized the sanctity of all life.

98. New Jerseyans for a Death Penalty Moratorium was another notable activist group.

99. New Jersey Death Penalty Study Commission, N

EW JERSEY LEGISLATURE,

https://www.njleg.state.nj.us/committees/njdeath_penalty.asp (last visited Aug. 18, 2019).

100. Henry, supra note 95, at 415.

101. See State of New Jersey, “New Jersey Death Penalty Study Commission Report,”

(January 2007), https://www.njleg.state.nj.us/committees/dpsc_final.pdf.

102. See generally, Lesniak, supra note 81.

103. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP)

supported the death penalty repeal measure in 2007, although it did not play as big a role in

New Jersey as it did in Maryland. Kirk Bloodsworth was also a very active figure in the

abolition movement, giving multiple speeches at universities and study commission panels.

3 - Sarat_etal__HJCP1-1.docx 12/6/2019 10:10 AM

52 Hastings Journal of Crime and Punishment [Vol. 1:1

The impact of New Jersey’s abolition was “largely symbolic” since

there had been no executions in the previous forty years.

104

Nonetheless, a

year after abolition, Senator Lesniak called it “one of the most significant

achievements of my life.”

105

Three years after the repeal that achievement

seemed to be put in jeopardy when Senators Robert Singer (R-Ocean) and

Anthony Bucco (R-Sussex) introduced a bill to reinstate capital punishment

following the murder of a Lakewood, New Jersey police officer, Chris

Matlosz.

106

Their legislation called for death in cases where children or

police officers were murdered, as well as when death results from a

terrorist attack.

107

It had nine co-sponsors, but ultimately failed.

108

Death Penalty Arguments Before and After Abolition in New Jersey

We examined the arguments about the death penalty that appeared in

the two largest circulation newspapers in New Jersey, The Record and The

Star Ledger, over the five years proceeding and five years following

abolition. In that period, we identified 750 discrete arguments, 599 of

which were published before the date of abolition, December 17, 2007, and

151 of which were published after that date. Overall, proponents of

abolition were much more active in advancing their cause than were the

He was wrongly convicted of raping and murdering a child in 1985, and spent almost nine

years in prison, two on death row, before DNA evidence exonerated him.

104. Henry, supra note 95.

105. Rudy Larini, A Year Later, State Assesses Justice Without Death Penalty, STAR

LEDGER (Dec. 15, 2008), https://www.atlanticphilanthropies.org/news/year-later-state-asse

sses-justice-without-death-penalty.

106. Chris Megerian, Lakewood Police Officer Chris Matlosz Shot to Death ‘Execution-

Style’ While on Duty, NJ.

COM (Jan. 15, 2011), https://www.nj.com/news/2011/01/lake

wood_police_office_chris_m.html.

107. Death Penalty Debate Is Revived In N.J., Y

ESHIVA WORLD NEWS (Apr. 2, 2011),

https://www.theyeshivaworld.com/news/headlines-breaking-stories/88715/death-penalty-de

bate-is-revived-in-n-j.html.

108. Support for capital punishment remains high in New Jersey. Fifty-seven percent

favored it in a 2015 Fairleigh Dickinson University PublicMind poll. Randy Bergmann,

Don’t Resurrect New Jersey’s Death Penalty, A

SBURY PARK PRESS, (Feb. 27, 2018),

https://www.app.com/story/opinion/editorials/2018/02/27/death-penalty-new-jersey/377331

002/; In 2018, Assemblymen Ronald Dancer and Ned Thomson and Sen. Robert Singer

introduced legislation calling for the reinstatement of capital punishment. Bob Jordan, NJ

Death Penalty: These GOP Lawmakers Want to Bring It Back, A

SBURY PARK PRESS, (Feb.

27, 2018), https://www.app.com/story/news/politics/new-jersey/2018/02/27/nj-death-penal

ty-these-gop-lawmakers-want-back/374409002/; Travis Fredschun, New Jersey Mansion

Murders Spur Calls for State to Reinstate Death Penalty, F

OX NEWS (Dec. 9, 2018),

https://www.foxnews.com/us/new-jersey-mansion-murders-spur-calls-for-state-to-reinstate-

death-penalty.

3 - Sarat_etal__HJCP1-1.docx 12/6/2019 10:10 AM

Winter 2020] After Abolition 53

death penalty’s supporters. Before abolition, there were 485 pro-abolition

arguments and 114 anti-abolition ones; after abolition, these numbers

dropped to 93 and 58 respectively (see TABLE 1).

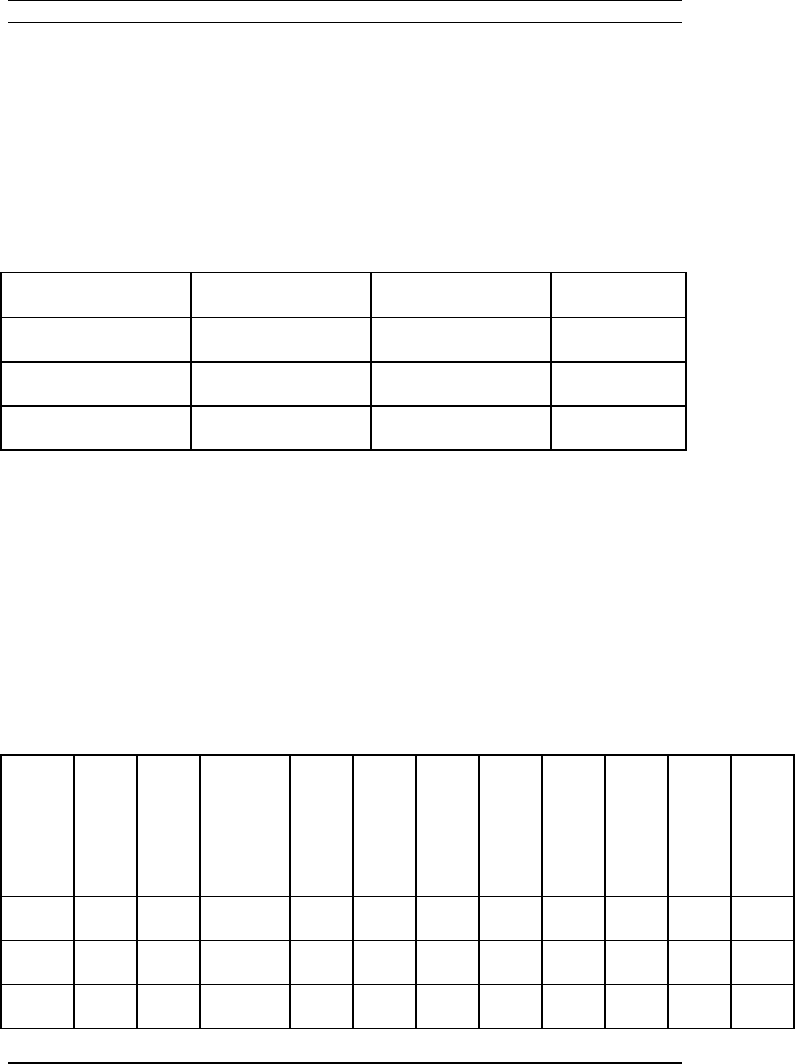

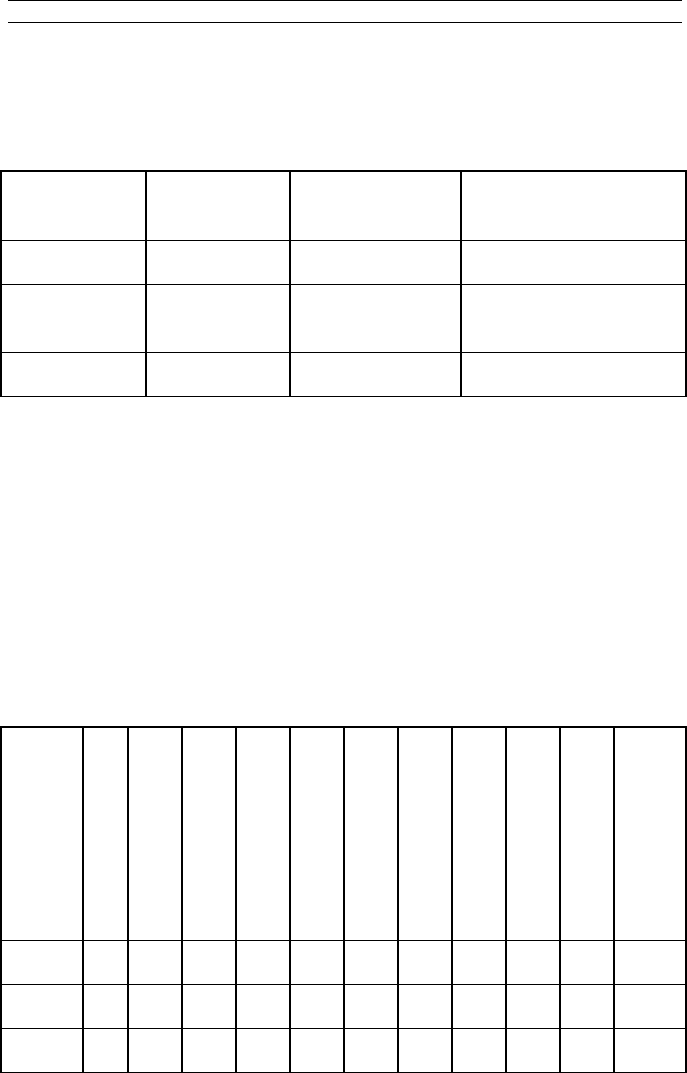

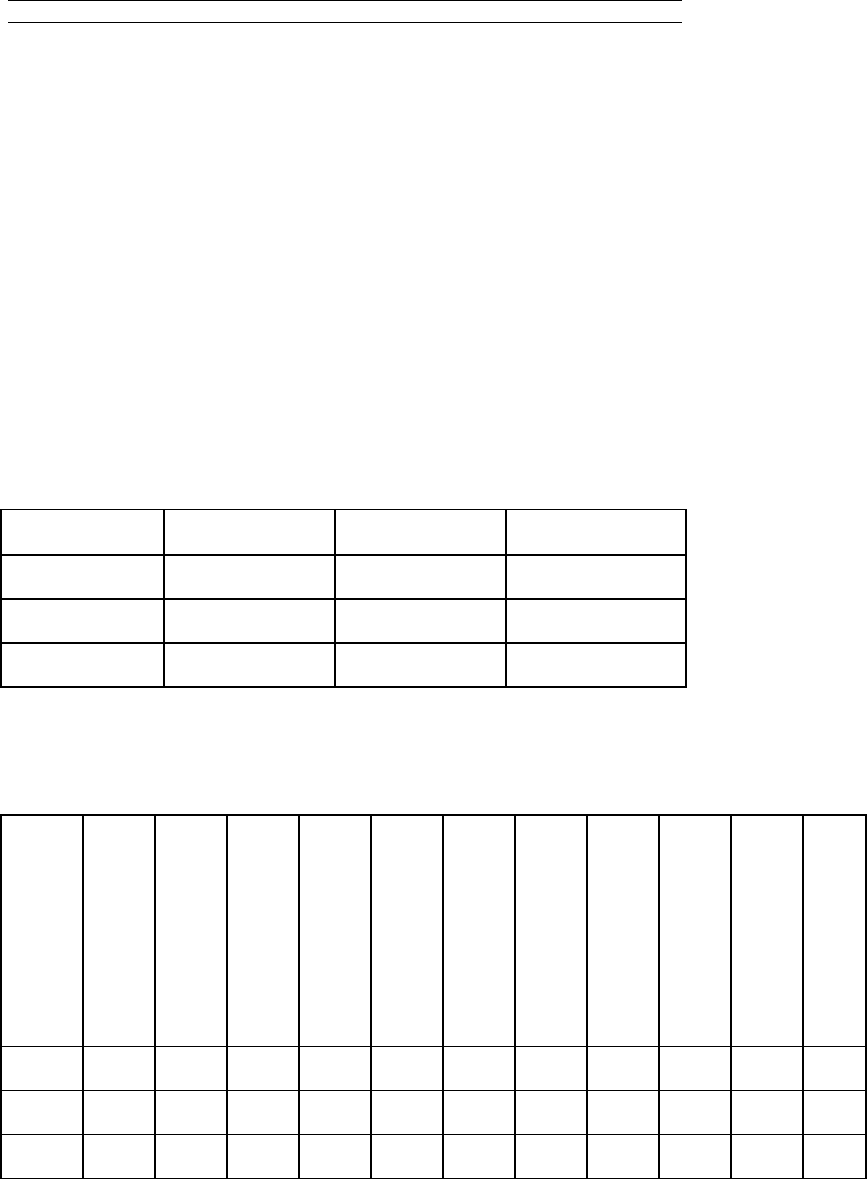

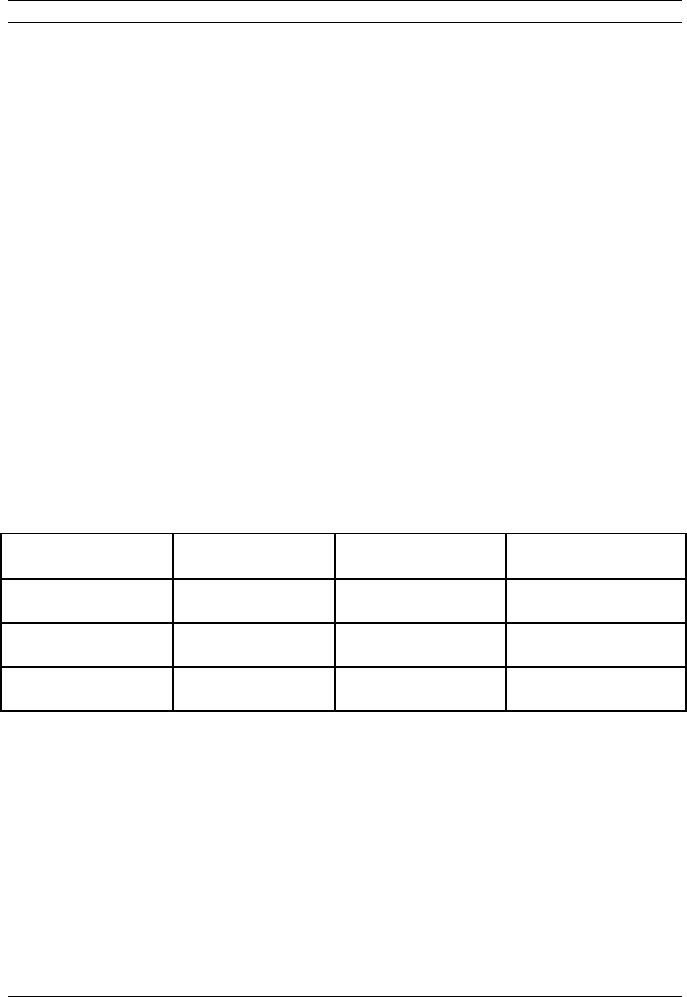

TABLE 1 NEW JERSEY TOTAL ARGUMENTS

Before Abolition After Abolition Total

For Abolition 485 93 578

Against Abolition 114 58 172

Total 599 151 750

The numbers of pro-abolition and anti-abolition arguments rose and

fell in synchrony through this ten-year period. Five years prior to its

abolition, the death penalty was a much less salient subject for New

Jersey’s citizens than in the two years before that decision. After abolition,

controversy abated quickly. As would be expected, both reached their

highest points in the year just before the decision to end capital punishment

occurred, with pro-abolition arguments numbering 171 and anti-abolition

arguments numbering 47. After abolition, the numbers of arguments for

both sides fell dramatically to less than 20 per year (see TABLE 2).

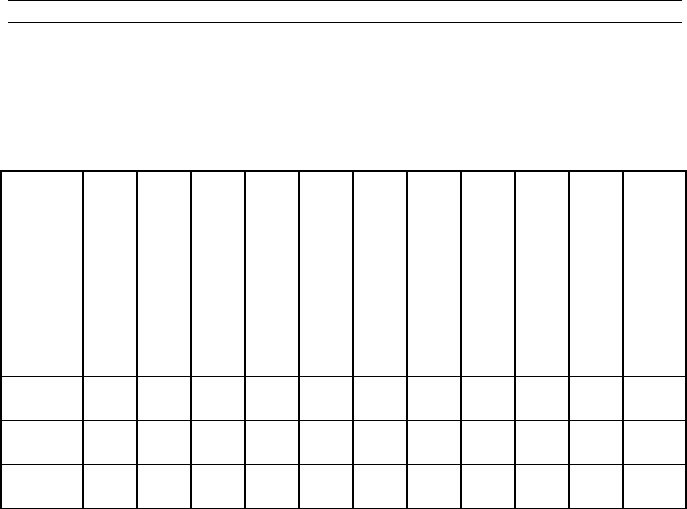

TABLE 2. New Jersey ARGUMENTS BY YEAR

109

Y1

(12/16/

2002-

12/17/

2003)

Y2

(12/16/

2003-

12/17/

2004)

Y3

(12/16

/2004-

12/17/

2005)

Y4

(12/15/

2006-

12/17/

2006)

Y5

(12/16/

2006-

12/17/

2007)

Y6

(12/16/

2007-

12/17/

2008)

Y7

(12/16/

2008-

12/17/

2009)

Y8

(12/16/

2009-

12/17/

2010)

Y9

(12/16/

2010-

12/17/

2011)

Y10

(12/16/

2011-

12/17/

2012) Total

For

63 52 73 127 171 63 11 2 10 6 578

Against

23 8 14 22 47 37 8 1 6 6 172

Total

86 60 87 149 218 100 19 3 16 12 750

109. We denote years as Y1-Y10 meaning the first through tenth year of study. We

choose to express our data this way, instead of by calendar year, because our ten-year span

is defined as five years before the exact date of abolition, to five years after. This means

that Y5, the last full year before abolition, ends one day before abolition date in each state.

Because abolition did not take place on January 1st in any of our states, each year of study

contains part of two calendar years.

3 - Sarat_etal__HJCP1-1.docx 12/6/2019 10:10 AM

54 Hastings Journal of Crime and Punishment [Vol. 1:1

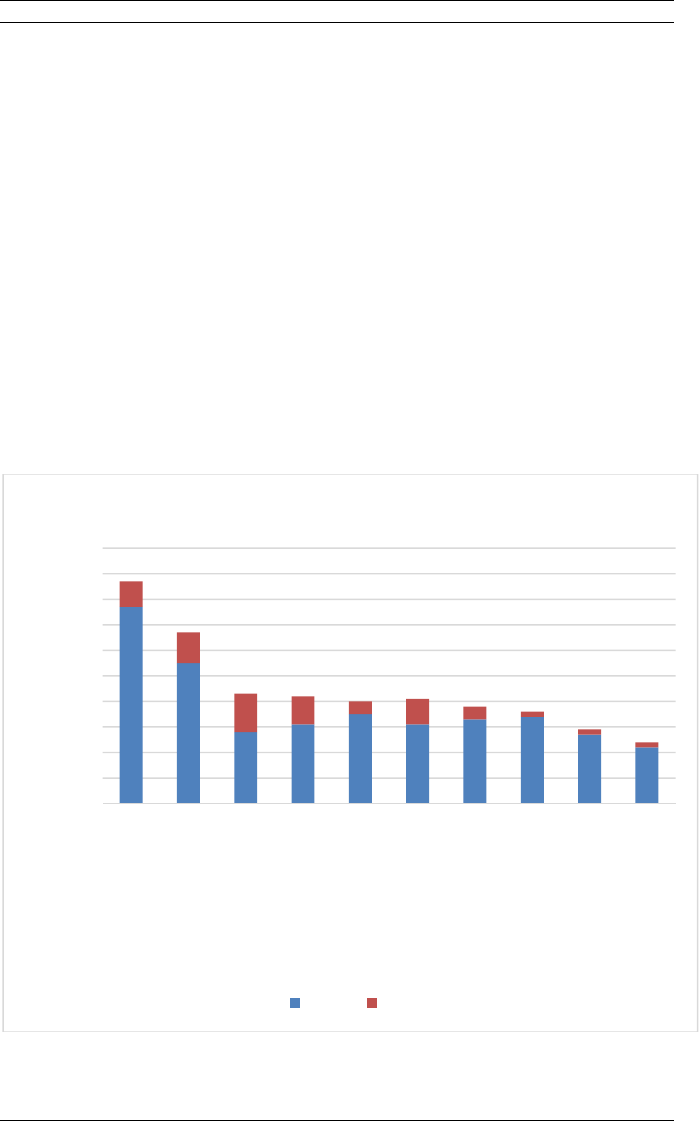

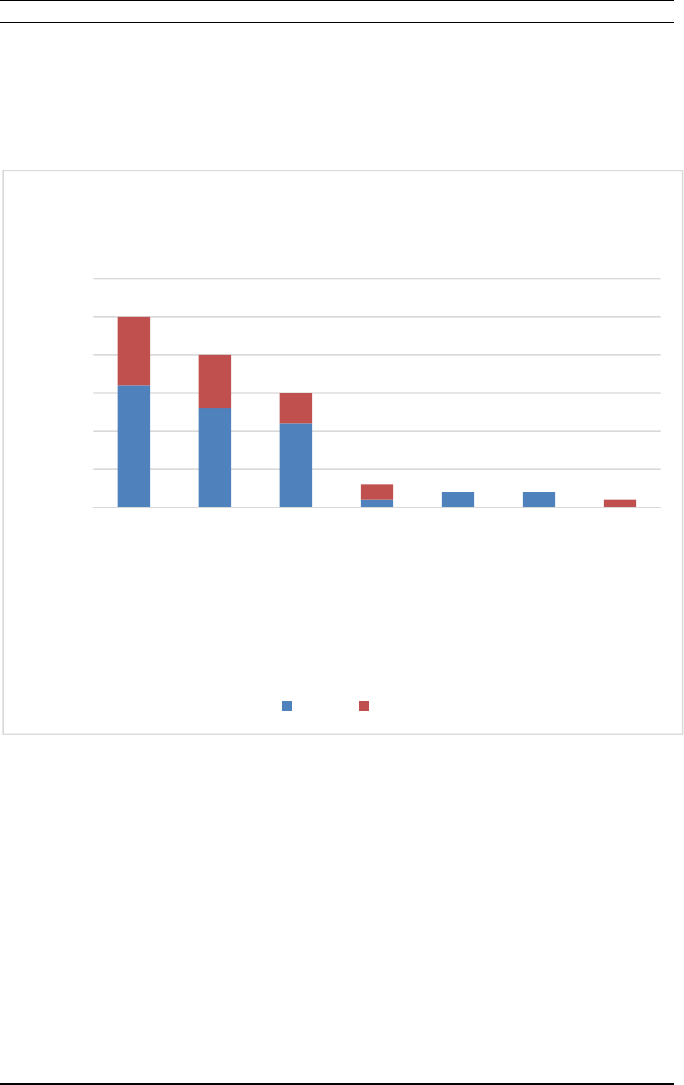

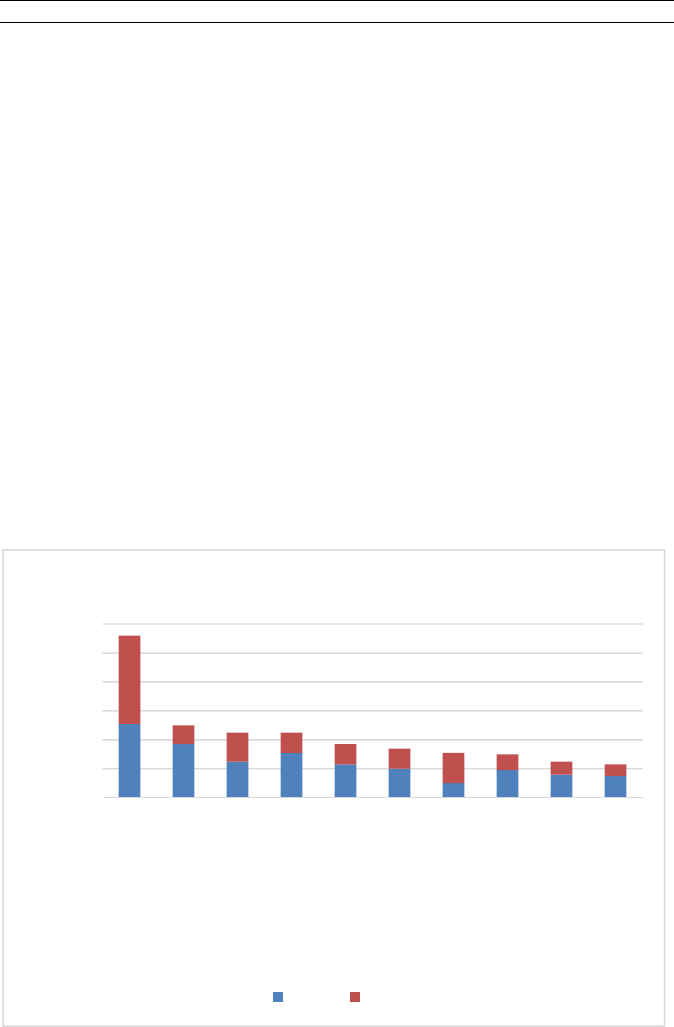

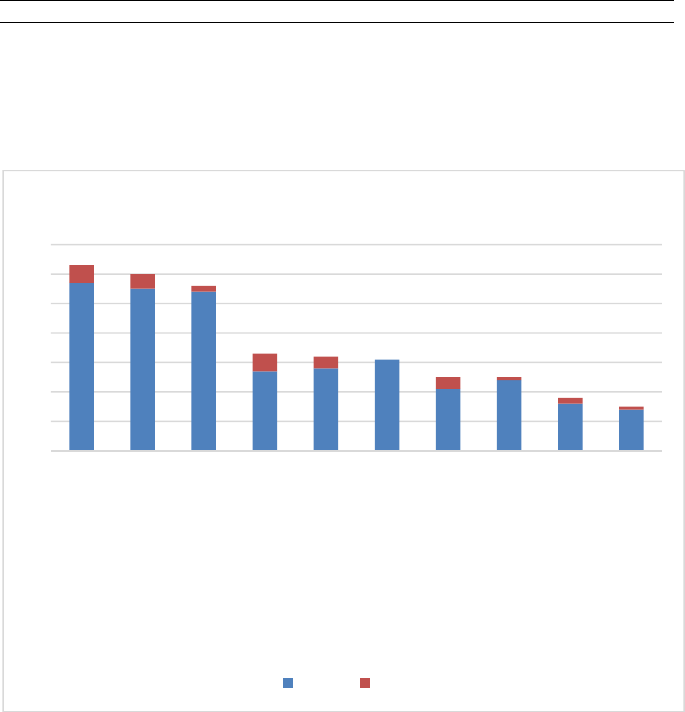

Innocence arguments (77) were the most common arguments made in

support of abolition in the period before it was accomplished. Arguments

about the death penalty’s economic costs were also frequently made (67)

(see FIGURE 1). Both of these arguments exemplify what Sarat has called

“the new abolitionism.”

110

New abolitionist arguments tend to be more

pragmatic and less philosophical than traditional arguments against the

death penalty. They focus on defects in the way the death penalty system

works rather than the moral evil of execution. Innocence arguments

experienced the most notable change in frequency from the pre-abolition

period to the post-abolition period. This argument only appeared 10 times

after abolition.

FIGURE 1

110. Austin Sarat, The “New Abolitionism” and the Possibilities of Legislative Action:

The New Hampshire Experience, 63 O

HIO ST. L.J. 343, 355 (2002).

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

Innocence

Economy

StandardsofDecency

Humanism

Religion

victims'families

Other

NonspecificFallibility

Deterrence

NonspecificLackof

Justification

ArgumentVolume

MostFrequentArgumentsforAbolition

Before After

3 - Sarat_etal__HJCP1-1.docx 12/6/2019 10:10 AM

Winter 2020] After Abolition 55

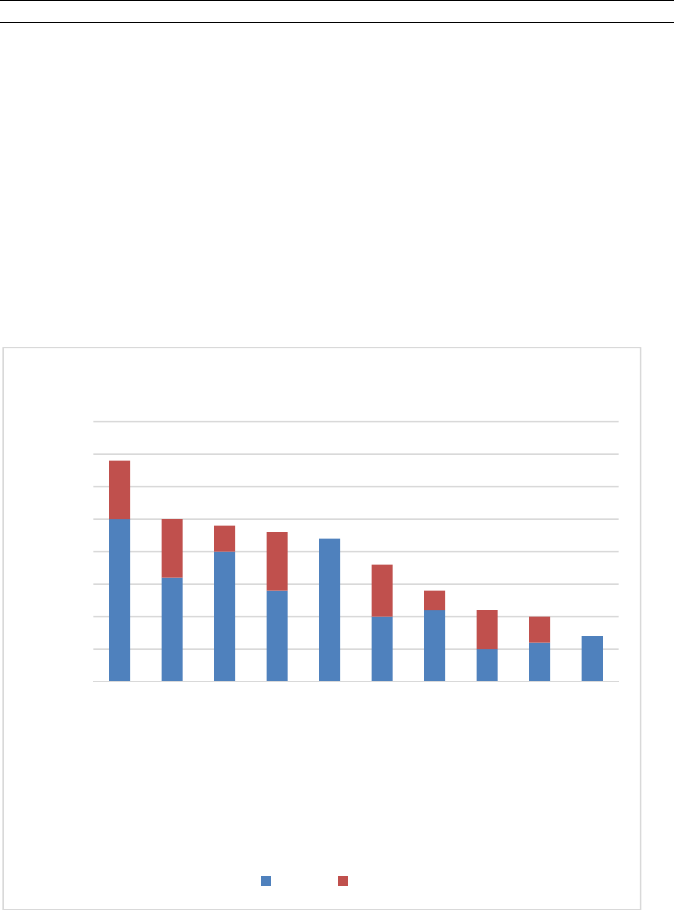

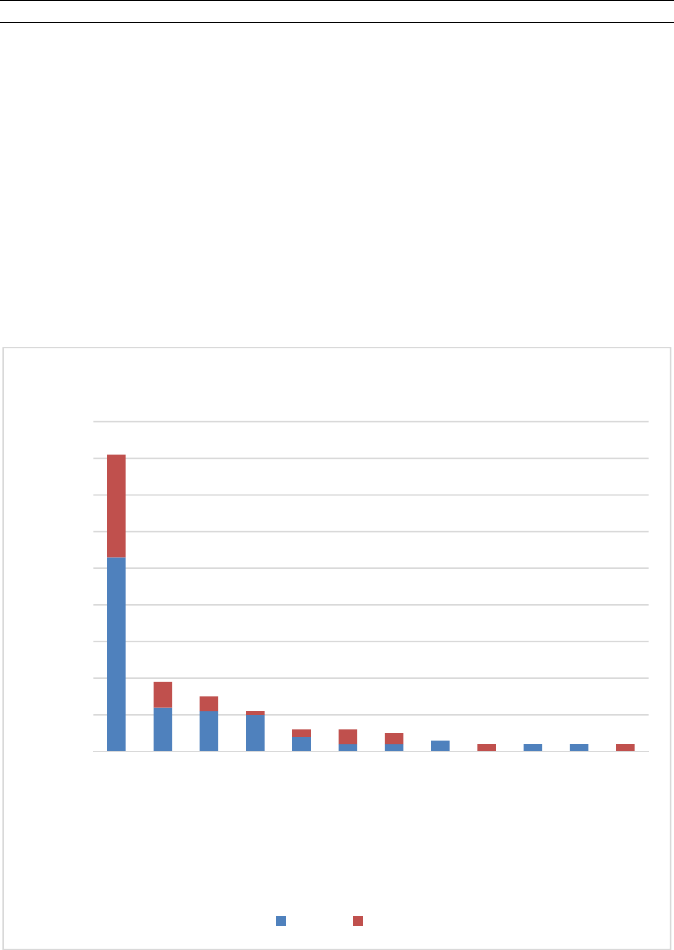

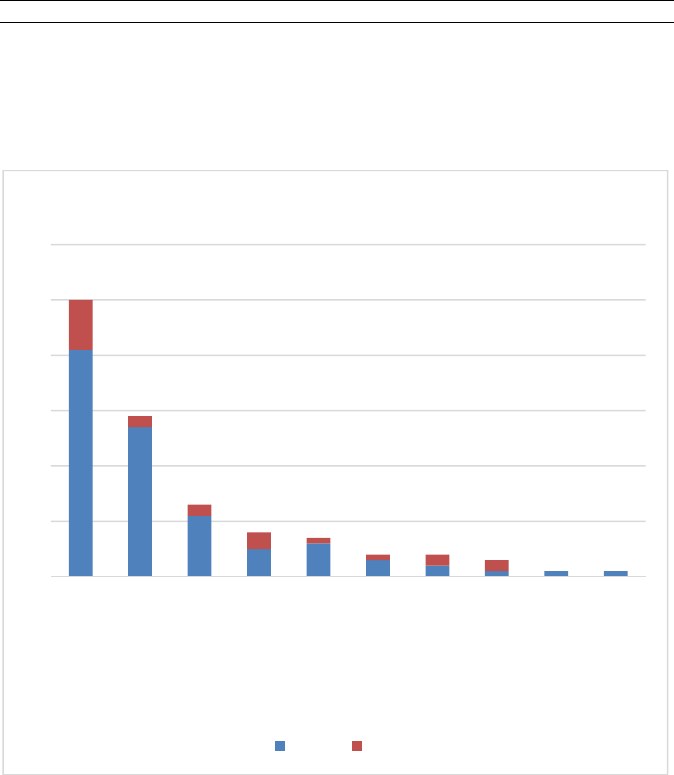

Proportionality (47) was the most common pro-death penalty

argument in the period before abolition. The next most frequent among

pro-death penalty arguments was repeat offense, which only occurs 16

times. The fact of abolition did not alter the kinds of arguments made

against ending the death penalty. Proportionality (18) and repeat offense

(14) remained the most common arguments in favor of reinstating capital

punishment after its abolition. (see FIGURE 2).

FIGURE 2

The debate about New Jersey’s death penalty had an odd quality to

it. Indeed, to call it a debate may not be quite right. As consideration of

whether to repeal capital punishment proceeded, abolitionists and

supporters of the death penalty operated in different argumentative

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

Proportionality

RepeatOffense

Deterrence

Victims'Families

Religion

Other

Economy

Humanism

PublicOpinion

NonspecificPublicProtection,

Redemption,Standardsof…

ArgumentVolume

MostFrequentArgumentsAgainstAbolition

Before After

3 - Sarat_etal__HJCP1-1.docx 12/6/2019 10:10 AM

56 Hastings Journal of Crime and Punishment [Vol. 1:1

universes. Both before and after abolition, they largely talked past each

other instead of directly engaging arguments made by the other side.

Moreover, the rapid decrease in the total number of arguments

about the death penalty following its abolition in both The Record and The

Star Ledger suggests that New Jersey’s repeal was mostly met with

acquiescence. Unlike an increase in arguments against abolition or in favor

of reinstatement that may be indicative of backlash, the number of pro-

death penalty arguments did not rise relative to anti-death penalty

arguments after abolition. This remained true even after the 2011 shooting

of police officer Matlosz and the subsequent call for the death penalty’s

reinstatement.

New Mexico

At the time New Mexico abolished the death penalty in 2009,

111

64% of New Mexicans supported replacing it with life in prison without the

possibility of parole and restitution to victims’ families.

112

The preceding

years had witnessed three unsuccessful repeal efforts. In 2005,

Representative Gail Beam (D-Albuquerque) introduced an abolition bill in

the state legislature.

113

His efforts were strongly supported by Catholic

groups which generally played a prominent role in the campaign to end

New Mexico’s death penalty.

114

Archbishop Michael J. Sheehan said at the

time Beam introduced her bill, “ending the death penalty is one of the New

Mexico Catholic Conference’s top legislative priorities” and, with a few

other bishops, he met with Governor Bill Richardson in an attempt to win

his support for Representative Beam’s repeal bill.

115

While that bill was

111. New Mexico Abolishes Death Penalty, CBS NEWS (Mar. 18, 2009, 2:38 PM),

https://www.cbsnews.com/news/new-mexico-abolishes-death-penalty/.

112. Death Penalty Abolished in New Mexico - Governor Says Repeal Will Make the

State Safer, D

EATH PENALTY INFORMATION CENTER, (Mar. 19, 2009), https://deathpenalty

info.org/news/death-penalty-abolished-in-new-mexico-governor-says-repeal-will-make-the-

state-safer; Archdiocese of Balt., New Mexico’s Decision to Abolish Death Penalty Marked

at Rome’s Colosseum, C

ATHOLIC REVIEW, (Jan. 19, 2012), https://www.archbalt.org/new-

mexicos-decision-to-abolish-death-penalty-marked-at-romes-colosseum/.

113. The effort actually echoed a similar effort four years previous, where a death-

penalty ban came within one vote of passing the Senate.

114. In addition to garnering notable religious support, the death penalty repeal effort in

New Mexico also had the backing of many death-penalty activist groups, such as the New

Mexico Coalition to Repeal the Death Penalty.

115. Steve Terrell, Sheehan, Bishops Seek Support for Death Penalty Repeal, S

ANTA FE

NEW MEXICAN (Jan. 28, 2005), at A1.

3 - Sarat_etal__HJCP1-1.docx 12/6/2019 10:10 AM

Winter 2020] After Abolition 57

adopted by the state’s House of Representatives by a 38-31 margin, it died

in a State Senate committee.

116

Even if Representative Beam’s repeal bill had been enacted in

2005, it was not clear that the governor would have signed it. Pundits

predicted that doing so would be tantamount to a “political death warrant”

for someone like Governor Richardson, who had national political

ambitions.

117

As one commentator observed, “Richardson was hardly an

anti-death penalty crusader looking for any opportunity to abolish capital

punishment. In fact, prior to 2009, Richardson was a ‘strong supporter’ of

the death penalty. He voted in favor of capital punishment as a U.S.

Congressman in 1994 and said he would have vetoed abolition legislation

during his first term as governor, from 2003 to 2007.”

118

Although, in 2007, a similar bill was also derailed before even

reaching the Senate floor,

119

the abolition movement in New Mexico was

reinvigorated after New Jersey’s successful efforts to end the death

penalty.

120

The abolition effort received vigorous support from Catholic

groups. The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops issued a statement

supporting abolition: “Pope Benedict XVI and his predecessor, Pope John

Paul II, have called for the end to the use of the death penalty as a sign of

greater respect for all human life.”

121

Representative Gail Chasey’s repeal

bill passed the House 40-28, with most Democrats voting for it and most

Republicans against it.

122

The New Mexico Senate concurred in early

2009.

123

Two days later, Governor Richardson signed the bill into law.

124

116. Death Penalty Study Guide, The League of Women Voters of New Mexico at 2

(2006), https://www.lwvnm.org/deathpenalty/DeathPenalty.pdf.

117. Steve Terrell, Death-Penalty Debate Comes for the Governor, S

ANTA FE NEW

MEXICAN (Feb. 27, 2005), at A1

118. Nicholas M. Parker, The Road to Abolition: How Widespread Legislative Repeal of

the Death Penalty in the States Could Catalyze a Nationwide Ban on Capital Punishment, 5

L

EGIS. AND POL’Y BRIEF 65, 86 (2013).

119. Press Release, Equal Justice Initiative, New Mexico Abolishes Death Penalty

(March 18, 2009) (https://eji.org/news/new-mexico-abolishes-death-penalty) (“An online

poll by the Albuquerque Journal showed today that 66% of some 5,300 respondents

supported Richardson signing the bill.”).

120. See Emily Louise Pryor, Democrats and the Death Penalty: An Analysis of State

Democratic Leaders’ Death Penalty Platforms and Public Opinion, D

ICKINSON SCHOLAR

(May 18, 2014), at 28-33.

121. Steve Terrell, Death Penalty Groups, Officials Look to Sway Richardson, S

ANTA FE

NEW MEXICAN (Mar. 17, 2009), at A1.

122. Steve Terrell, House Votes Against Capital Punishment, SANTA FE NEW MEXICAN

(Feb. 12, 2009), at A6.

123. Dan Boyd, Death Penalty Out?, ALBUQUERQUE J. (Mar. 14, 2009), https://w

3 - Sarat_etal__HJCP1-1.docx 12/6/2019 10:10 AM

58 Hastings Journal of Crime and Punishment [Vol. 1:1

At the signing ceremony, Governor Richardson said, “Faced with the

reality that our system for imposing the death penalty can never be perfect,

my conscience compels me to replace the death penalty with a solution that

keeps society safe.”

125

An editorial in the Santa Fe New Mexican “opined that repeal ‘isn’t

really that big a deal’ given how infrequently the State employed the death

penalty to begin with.”

126

Nevertheless, the abolition of capital punishment

was met with more resistance than had been the case in New Jersey.

Indeed, “talk of reversing the repeal began almost immediately in New

Mexico

—despite broad public support for abolition.”

127

Soon thereafter Governor Richardson signed the repeal bill,

Bernalillo County Sheriff Darren White proposed restoring the death

penalty through a ballot referendum.

128

This idea was supported by both

the Santa Fe Police Chief, Eric Johnson, and the Santa Fe County Sheriff,

Greg Solano, who claimed that the death penalty was a vital law

enforcement tool as well as an effective deterrent.

129

However, the Santa

Fe County District Attorney, Angela Pacheco, refused to support the

referendum effort, which eventually failed.

130

Reflecting the often top-down nature of backlash, Republican

Governor Susana Martinez launched a second reinstatement effort two

years later. As the governor stated in her inaugural address:

“We should . . . send the message that some crimes

deserve the ultimate punishment. When a monster rapes and

murders a child or a criminal kills a police officer, the death

ww.abqjournal.com/news/xgr/14114624xgr03-14-09.htm.

124. Oliver Burkeman, New Mexico Bans Death Penalty, THE GUARDIAN (Mar. 19,

2009), https://www.theguardian.com/world/2009/mar/19/new-mexico-death-penalty-ban.

125. Archdiocese of Balt., New Mexico Repeals Death Penalty after Governor Changes

His Mind, C

ATHOLIC REVIEW (Jan. 19, 2012), https://www.archbalt.org/new-mexico-

repeals-death-penalty-after-governor-changes-his-mind/; see generally Bill Richardson, I

Carried out the Death Penalty as a Governor. I Hope Others Put It to Rest, WASH. POST

(June 13, 2017), https://www.washingtonpost.com/posteverything/wp/2017/06/13/__tras

hed-2/.

126. Nicholas M. Parker, The Road to Abolition: How Widespread Legislative Repeal of

the Death Penalty in the States Could Catalyze a Nationwide Ban on Capital Punishment, 5

L

EGIS. AND POL’Y BRIEF 65, 87 (2013).

127. Id.

128. Jason Auslander, Death Penalty, Police Back Plan to Reverse Ban, S

ANTA FE NEW

MEXICAN (Mar. 21, 2009), at C1.

129. Id.

130. Id.

3 - Sarat_etal__HJCP1-1.docx 12/6/2019 10:10 AM

Winter 2020] After Abolition 59

penalty should be an option for the jury. That’s why I am calling

on the legislature to repeal the repeal and reinstate the death

penalty.”

131

In letters to the editor of the Santa Fe New Mexican, citizens

voiced their opposition to the governor’s effort. One letter observed that

“Gov. Susana Martinez’s intention to reinstate the death penalty in New

Mexico sounds more like a campaign speech than the comment of a

governor facing huge budget problems.”

132

Another letter stated “the death

penalty is a barbaric, counter-productive relic of ancient and medieval

times. All modern, progressive countries have abolished it. The state of

New Mexico abolished it. Gov. Susana Martinez must not attempt to bring

it back!”

133

In the end, Governor Martinez’s proposal also encountered

fierce opposition and failed in a legislature controlled by Democrats.

134

Arguments About the Death Penalty in New Mexico Before and After

Abolition

We examined arguments about the death penalty published in The

Albuquerque Journal and The Santa Fe New Mexican, the state’s highest

circulation newspapers, over a ten-year period. There we found a total of

306 arguments starting in the five years leading to, and including the year

of, the New Mexico’s abolition of capital punishment and ending five years

after abolition. Over the ten-year period of our study, 234 arguments

supporting abolition appeared in The Albuquerque Journal and The Santa

Fe New Mexican as did 72 arguments against doing so. Prior to abolition,

there were 171 arguments for abolition and 49 against, while after abolition

63 arguments were made in support of that decision and 23 were offered in

opposition (see TABLE 3).

131. Governor Susana Martinez, State of the State Address at the New Mexico House of

Representatives (Jan. 18, 2011) (transcript at https://www.koat.com/article/susana-martinez-

s-full-state-of-the-state-speech/5035274).

132. Rob Steiner, Looking In: Letters to the Editor No Time to Rehash Death-Penalty

Debate, S

ANTA FE NEW MEXICAN (Jan. 25, 2011), at A10

133. Reuben Hersh, Letters to the Editor: Preserve Repeal, S

ANTA FE NEW MEXICAN

(Feb. 8, 2011), at A13

134. For a discussion of subsequent efforts to restore New Mexico’s death penalty see

Lucy Schouten, Why New Mexico Wants to Restore the Death Penalty, C

HRISTIAN SCIENCE

MONITOR (Aug. 18, 2016), https://www.csmonitor.com/USA/Justice/2016/0818/Why-New-

Mexico-wants-to-restore-the-death-penalty; Andrew Oxford, Effort to Reinstate Death

Penalty Dies Quickly, N.

M. POLITICAL REPORT (Feb. 3, 2018), https://nmpoliticalrep

ort.com/2018/0203/effort-to-reinstate-death-penalty-dies-quickly/

3 - Sarat_etal__HJCP1-1.docx 12/6/2019 10:10 AM

60 Hastings Journal of Crime and Punishment [Vol. 1:1

TABLE 3 New Mexico Total Arguments

Before

Abolition After Abolition Total

For Abolition 171 63 234

Against

Abolition 49 23 72

Total 220 86 306

The largest concentration of arguments (100) about New Mexico’s

death penalty appeared between 2004 and 2005, several years before

abolition. After that period, arguments in the newspapers dropped to a low

(11) in Y2, before climbing back up to 74 arguments the year the death

penalty was abolished. Total arguments dropped to 29 in Y6 then spiked to

50 in Y7, when Governor Martinez proposed restoration of capital

punishment. After the failure to reinstate capital punishment, arguments

concerning the death penalty declined to 0 in the period between 2013 and

2014, suggesting that New Mexico’s residents mostly accepted the decision

to end the state’s death penalty (see TABLE 4).

TABLE 4 New Mexico Argument by Year

Y1

(3/

8/2

00

4 –

3/7

/20

05)

Y2

(3/8/

200

5 –

3/7/

200

6)

Y3

(3/8/

200

6 –

3/7/

200

7)

Y4

(3/8/

200

7 –

3/7/

200

8)

Y5

(3/8/

200

8 –

3/7/

200

9)

Y6

(3/8/

200

9 –

3/7/

201

0)

Y7

(3/8/

201

0 –

3/7/

201

1)

Y8

(3/8/

201

1 –

3/7/

201

2)

Y9

(3/8/

201