MOVING AWAY FROM

THE DEATH PENALTY

Arguments, Trends and Perspectives

Moving Away from the Death Penalty:

Arguments, Trends and Perspectives

MOVING AWAY FROM THE

DEATH PENALTY

ARGUMENTS, TRENDS AND PERSPECTIVES

New York, 2015

MOVING AWAY FROM THE DEATH PENALTY:

ARGUMENTS, TRENDS AND PERSPECTIVES

© 2015 United Nations

Worldwide rights reserved. This book or any portion thereof may

not be reproduced without the express written permission of the

author(s), editor, or the publisher, except as permitted by law.

The ndings, interpretations and conclusions expressed herein are those of

the author(s) and do not necessarily reect the views of the United Nations.

The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this

publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever

on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the

legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities,

or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.

Editor: Ivan Šimonovi´c

Design and layout: dammsavage studio

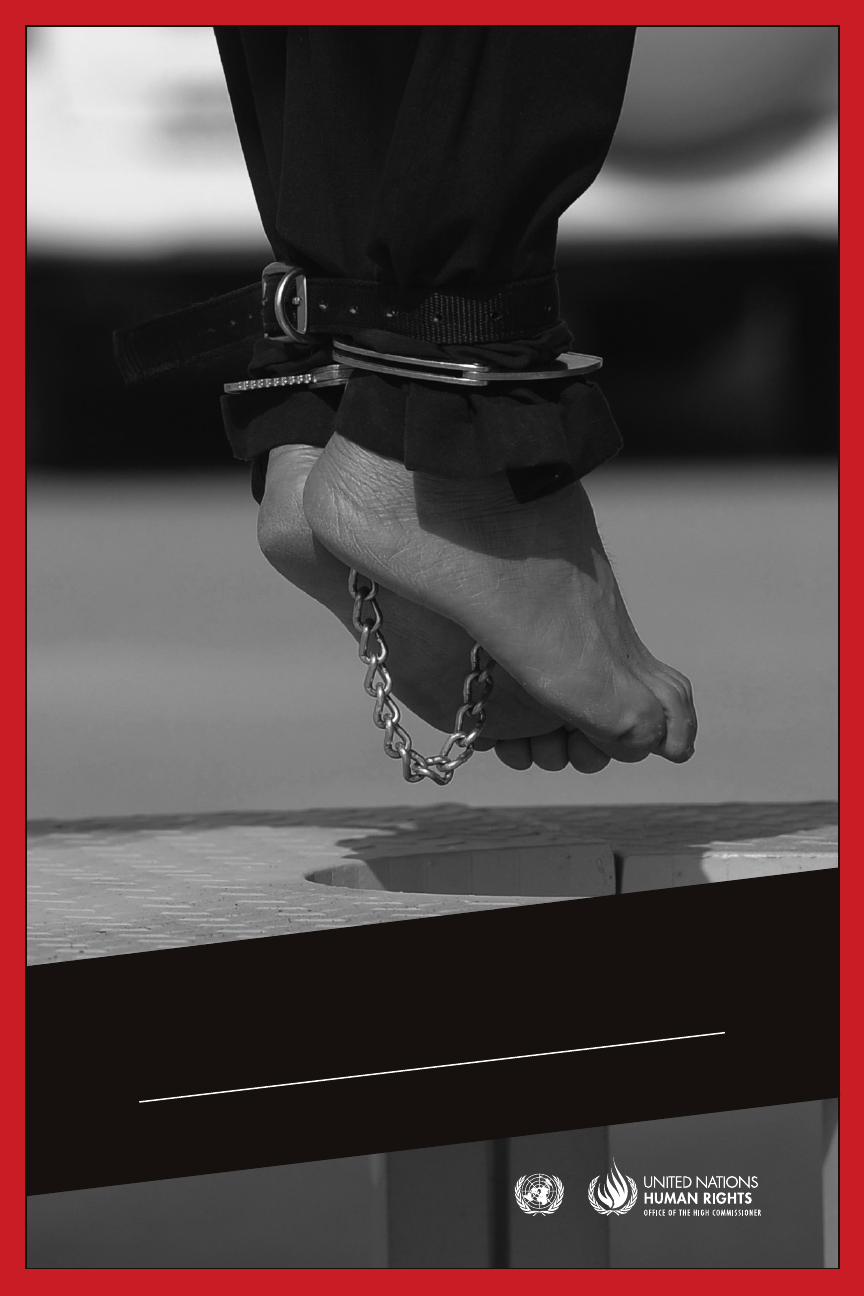

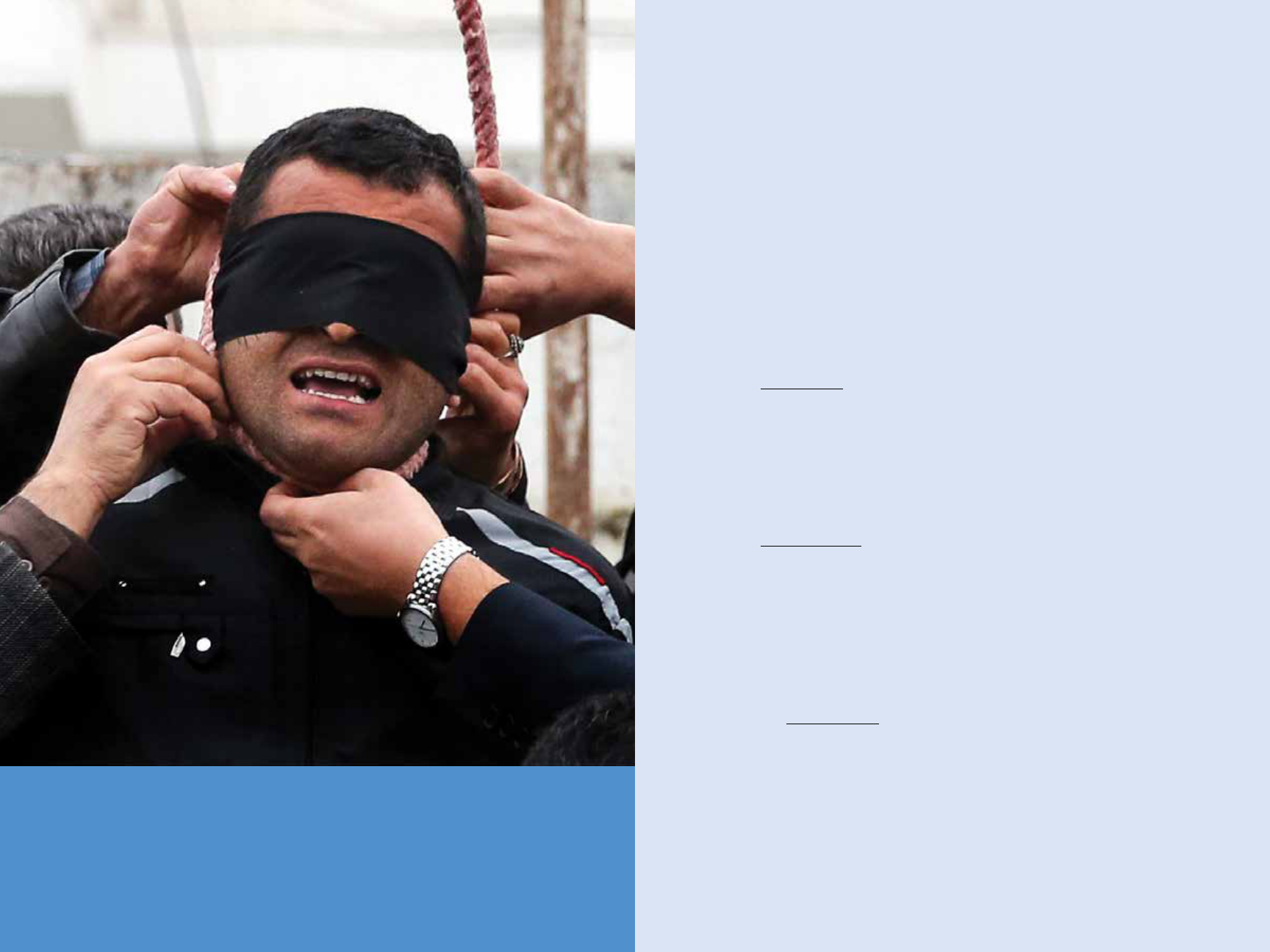

Cover image:

The cover features an adaptation of a photograph of the feet of a man convicted

of murder, seen during a hanging. Photo credit: EPA/Raed Qutena. The back

cover graphic line represents a declining percentage of United Nations Member

States that practice the death penalty (those that have not abolished it in law or

practice), from 89% in 1975, ending at 27% in 2015, in 10 year increments.

Electronic version of this publication is available at:

www.ohchr.org/EN/NewYork/Pages/Resources.aspx

Sales no.: E.15.XIV.6

ISBN: 978-92-1-154215-8

eISBN: 978-92-1-057589-8

CONTENTS

Preface – Ban Ki-moon, United Nations Secretary-General p.6

Introduction – An Abolitionist’s Perspective, Ivan Šimonovi´c p.8

Chapter 1 – Wrongful Convictions p.22

• Kirk Bloodsworth, Without DNA evidence I’d still be behind bars p.24

• Brandon Garrett, DNA evidence casts light on aws in system p.30

• Gil Garcetti, In the United States, growing doubts about the death penalty p.39

• Saul Lehrfreund, Wrongful convictions and miscarriages of justice

in death penalty trials in the Caribbean, Africa and Asia p.48

Chapter 2 – Myth of Deterrence p.66

• Carolyn Hoyle & Roger Hood, Deterrence and public opinion p.68

• Je Fagan, Deterrence and the death penalty in international perspective p.84

Chapter 3 – Discrimination p.100

• Damien Echols, The terrors of prison fade slowly p.103

• Stephen Braga, Damien Echols and the West Memphis Three Case p.107

• Stephen Bright, Imposition of the death penalty upon the poor, racial

minorities, the intellectually disabled and the mentally ill p.115

• Arif Bulkan, The death penalty in the Commonwealth Carribean:

Justice out of reach? p.130

• Usha Ramanathan, The death penalty in India: Down a slippery slope p.150

• Alice Mogwe, The death penalty in Botswana: Barriers to equal justice p.170

• Innocent Maja,The death penalty in Zimbabwe: Legal ambiguitites p.180

Chapter 4 – Values p.184

• Sister Helen Prejean, Death penalty: victims’ perspective p.187

• Mario Marazziti, World religions and the death penalty p.192

• Nigel Rodley, The death penalty as a human rights issue p.204

• Christof Heyns & Thomas Probert, The right to life and

the progressive abolition of the death penalty p.214

• Paul Bhatti, Towards a moratorium on the death penalty p.227

Chapter 5 – Leadership p.234

• Federico Mayor, Leadership and the abolition of the death penalty p.236

• Mai Sato, Vox populi, vox dei? A closer look at the ‘public opinion’

argument for retention p.250

• H.E. Mr. Didier Burkhalter, Federal Councilor and Minister of

Foreign Aairs of Switzerland, Leadership through dialogue p.259

• H.E. Mr. Tsakhia Elbegdorj, President of Mongolia,

Mongolia honours human life and dignity p.266

• Laurent Fabius, Minister of Foreign Aairs and International

Development of France, Towards universal abolition of the death penalty p.268

• Mohamed Moncef Marzouki, former President of the Republic

of Tunisia, Challenges related to abolition of the death penalty in

Arab and Islamic Countries: Tunisia’s model p.272

• Prime Minister Matteo Renzi, President of the Council of

Ministers of the Italian Republic, The role of leadership p.276

• H.E. Dr. Boni Yayi, President of the Republic of Benin,

A ght for the progress of humanity p.282

Chapter 6 – Trends and Perspectives p.284

• Salil Shetty, Global death penalty trends since 2012 p.286

Afterword, Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein, United Nations

High Commissioner for Human Rights p.295

Acknowledgements p.297

6 7

PREFACE

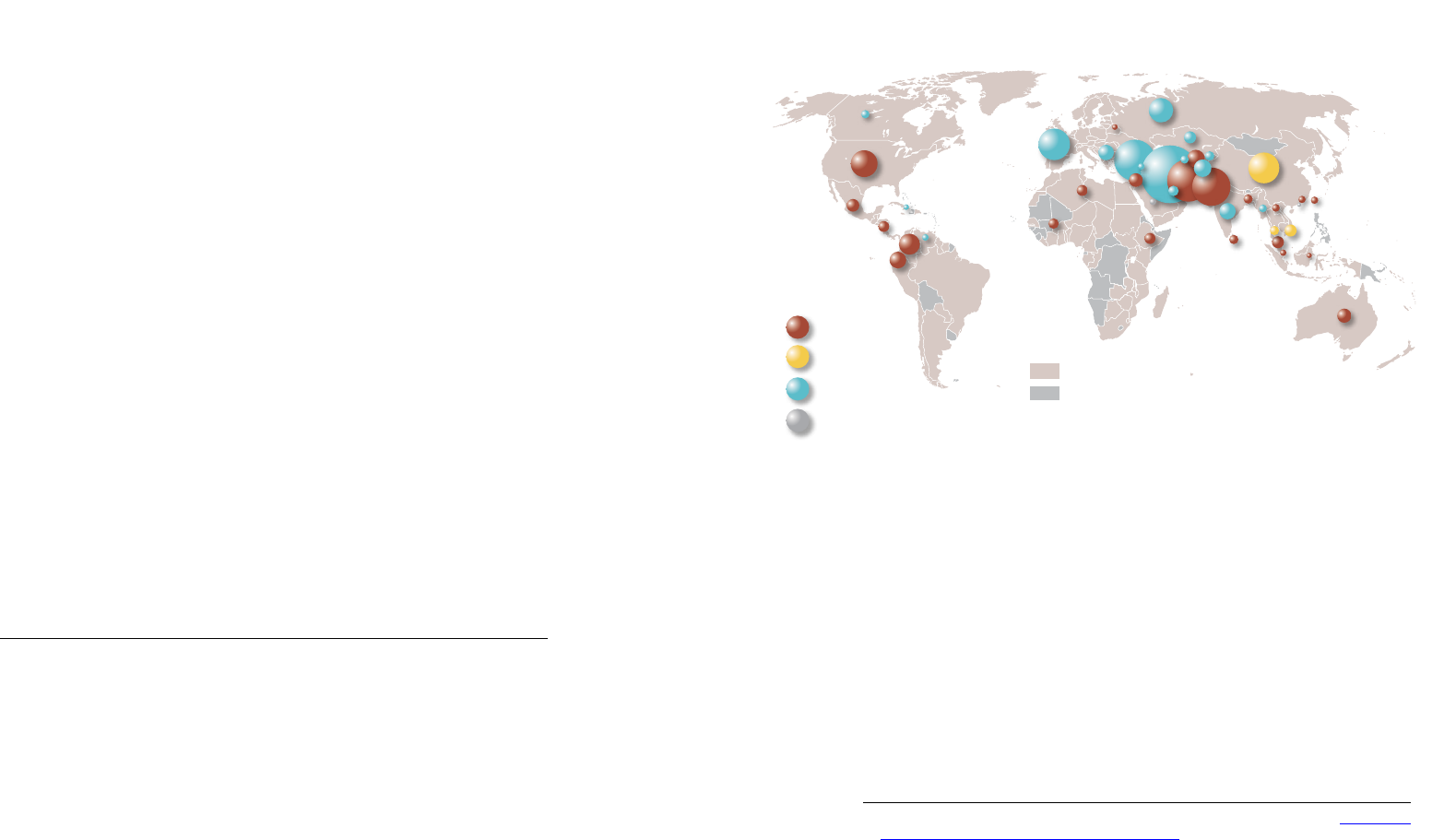

Today, more than four out of ve countries have either abolished

the death penalty or do not practice it. Globally, there is a rm trend

towards abolition, with progress in all regions of the world. Member

States representing a variety of legal systems, traditions, cultures and

religious backgrounds have taken a position in favour of abolition

of the death penalty. Some States that opposed the abolition of the

death penalty in the recent past have moved to abolish it; others have

imposed a moratorium on its use. The application of the death penalty

appears to be conned to an ever-narrowing minority of countries.

Those remaining States cite a number of reasons for retaining the

death penalty, including what they see as its deterrent eect; that it

is consistent with public opinion; that it is equally applied against all

perpetrators; and that there are sucient judicial safeguards to ensure

defendants are not wrongfully convicted.

Over the past two years, the Oce of the High Commissioner for

Human Rights has convened a series of important panel discussions

on the death penalty, seeking to address these issues. The events drew

on the experiences of government ocials, academic experts and civil

society from various regions which, in recent years, have made progress

towards abolition or the imposition of a moratorium. They covered

key aspects of the issue, including data on wrongful convictions and

the disproportionate targeting of marginalized groups of people. This

publication brings together the contributions of the panel members

as well as other experts on this subject. Taken as a whole, they make a

compelling case for moving away from the death penalty.

The death penalty has no place in the 21st century. Leaders across the

globe must boldly step forward in favour of abolition. I recommend

this book in particular to those States that have yet to abolish the

death penalty. Together, let us end this cruel and inhumane practice.

Ban Ki-moon

Secretary-General, United Nations

“The death penalty has no place in the 21st century. Leaders

across the globe must boldly step forward in favour of

abolition. I recommend this book in particular to those

States that have yet to abolish the death penalty. Together,

let us end this cruel and inhumane practice.”—Ban Ki-moon

United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon attending OHCHR’s global panel: “Moving away from

the death penalty – wrongful convictions”, New York, 28 June 2013 © UN Photo/Evan Schneider

8 9

INTRODUCTION:

AN ABOLITIONIST’S PERSPECTIVE

Why yet another book on the death penalty? The answer is simple: As

long as the death penalty exists, there is a need for advocacy against it.

This book provides arguments and analysis, reviews trends and shares

perspectives on moving away from the death penalty.

This book, rst published in 2014, has been updated and expanded,

providing victims’ and United Nations human rights mechanisms’

perspective, a new chapter on the role of leadership in moving away

from the death penalty. The new High Commissioner for Human

Rights, Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein, appointed in 2014, has provided

an afterword.

Abolishing the death penalty is a collective eort which requires

commitment, cooperation and time. As a student in 1977 in the

Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, I was allowed to write my

high school graduation essay on the abolition of the death penalty.

At the time, Yugoslavia practiced the death penalty and had limited

freedom of expression. Against this backdrop, I am especially thankful

for the courage and support of my teachers.

Much has happened since 1977: Yugoslavia broke up more than 20

years ago, and all its successor states have abolished the death penalty.

Globally, most countries have gradually been moving away from the

death penalty—by reducing the number of crimes punishable by

death, introducing additional legal safeguards, proclaiming a morato-

rium on executions or abolishing the death penalty altogether.

Amnesty International reports that in the mid-1990s, 40 countries

were known to carry out executions every year. Since then, this

number has halved. About 160 countries have abolished the death

penalty in law or in practice; of those, 100 have abolished it alto-

gether. In 2007, when the death penalty moratorium resolution

was rst adopted by the United Nations General Assembly, it was

supported by 104 states. In the most recent vote, in 2014, it was

“In the 21st century a right to take someone’s

life is not a part of the social contract

between citizens and a state any more....”

— Ivan Šimonovi´c

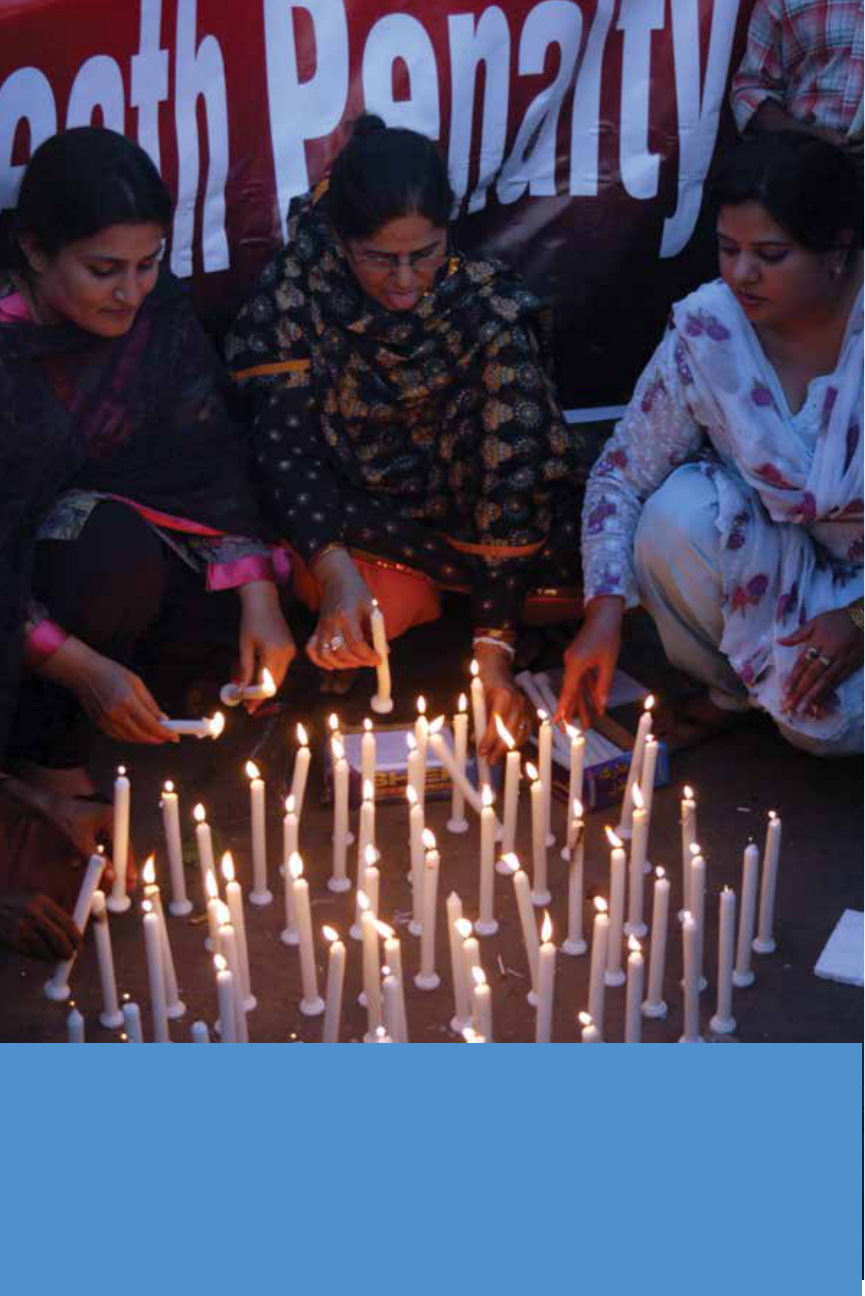

Human rights activists light candles in observance of the World Day against the Death Penalty. © EPA/MK Chaudhry

10 11

supported by 117 states.

1

In 2014 there were at least 607 documented

executions

2

. While the number of executing states remained the same

in 2014 as in 2013, the number of documented executions dropped

by 22percent.

While this is grounds for optimism, there are also reasons for concern.

The number of death sentences imposed in 2014 worldwide was at

least 2,446, which represents a 28percent increase over 2013.

3

Can

the recent steady global trend towards abolition be reversed?

Some human rights achievements dating back to the early 1990s

are currently facing renewed challenges.

4

Armed conicts involving

non-state actors, triggering ethnic and religious divisions, are prolifer-

ating globally. Many states and regimes face instability. Fear of violent

extremism, organized crime and especially drug tracking make

tough punishment for these crimes appealing. It creates an impression

of commitment and is much easier and cheaper than increasing the

eciency of the law enforcement and justice systems. It is still to be

seen whether these setbacks will stall or reverse the trend of moving

away from the death penalty. This book seeks to contribute to eorts

to prevent this from happening.

In 2012, 35 years after my graduation essay, now as United Nations

Assistant Secretary-General for Human Rights, I was able to con-

tribute to a discussion on the death penalty at the United Nations

in New York. The panel discussion on “moving away from the death

penalty” that I moderated in 2012 included a distinguished group

of member states representatives, experts, civil society activists

and a victim of wrongful conviction. The panel identied three

main reasons for member states’ decisions on the death penalty:

the possibility of wrongful convictions, crime deterrence or the

1 UN Doc. A/69/PV.73, pp.17-18 (18 December 2014)

2 Amnesty International, Death Sentences and Executions in 2014 (London, Amnesty International,

2015)

3 The number of death sentences imposed in Egypt—509—signicantly contributed to this

trend. By the end of 2014 Pakistan lifted a six-year moratorium. The real number of executions

is unknown. Some countries—including China, in which most executions take place—do

not publicly release data on executions. China appears to be moving cautiously away from the

death penalty, initially reducing the number of crimes punishable by death and introducing

additional safeguards, which may heavily and positively inuence overall trends.

4 A series of world conferences in the early 1990s made signicant progress on human rights. But

the principles agreed to there are currently being challenged.

lack thereof, and discrimination against marginalised groups in

its implementation

5

.

Recognizing their importance, the Oce of the High Commissioner

for Human Rights in New York organized debates on each of these

three issues, involving member states, non-governmental organiza-

tions and academia. We benetted from the valuable support of the

permanent missions to the United Nations of Chile, Italy and the

Philippines as co-organisers for two of these panels

6

. Together with

the permanent mission of Italy, we organised an additional panel on

national experiences with a moratorium on executions

7

. Finally, in

April 2015, at the United Nations Congress on Crime Prevention

and Criminal Justice in Doha, Qatar, we also organised a panel dis-

cussion on the death penalty, drugs and terrorism

8

.

United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon participated in four

of these events as the keynote speaker, and has provided a preface to

this book, which presents contributions by panellists at these events and

other prominent authorities on issues surrounding the death penalty.

The views expressed in these articles reect the personal positions of

their authors and not necessarily the institutional position of the Oce

of the High Commissioner for Human Rights or the United Nations.

As the editor of the book, I hope that you will nd their ideas interest-

ing and challenging, whether you agree with them or not.

The panels on which this book is based, apart from the one held in

Doha, took place in New York, thus beneting from the proximity

of a number of top-level death penalty experts, civil society activists

as well as two victims of wrongful conviction. Nevertheless, we are

fortunate to be able to present an even larger number of articles by

African, Asian, Caribbean and European authors.

5 See brochure on the panel Moving away from the death penalty: Lessons from National Experiences

(UN OHCHR, New York 2012, 25 p.)

6 OHCHR Global Panel: “Moving Away from the Death Penalty-Deterrence and Public Opin-

ion”, co-sponsored by the permanent missions of the Philippines and Chile, 24 January 2014

UNHQ, New York; OHCHR Global Panel: “Moving away from the Death Penalty - Discrim-

ination against Marginalised Groups”, 24 April 2014, UNHQ, New York

7 “Best Practices and Challenges in implementing a Moratorium on the Death Penalty”,

UNHQ, New York, 2 July 2014.

8 “Panel discussion: Death Penalty, Drugs and Terrorism”, 13

th

United Nations Congress on

Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice, Doha, Qatar, 14 April 2015.

12 13

The question of the death penalty’s deterrent eect, which is

addressed in chapter 2, has attracted scholarly and political attention

for centuries. Are public executions brutal relics of the past or e-

cient preventive measures? Does capital punishment for relatively

minor crimes increase the frequency of more severe crimes because

the risk to perpetrators is no greater? Does it expose crime witnesses

to greater risk? The great majority of countries have stopped public

executions and reduced the application of the death penalty to only

the most severe crimes, but does the death penalty deter crime at all?

Government actors often feel public pressure to retain the death

penalty as a crime control measure. However, there is no evidence

that it is in fact a deterrent. In countries that have abolished the

death penalty, this has in general not resulted in an increase in serious

crime. The most comprehensive survey on the relationship between

the death penalty and murder rates, which was carried out for the

United Nations in 1988 and updated in 1996, found that “research

has failed to provide scientic proof that executions have a greater

deterrent eect than life imprisonment. Such proof is unlikely to be

forthcoming. The evidence as a whole gives no positive support to

the deterrent hypothesis.”

10

Statistics from countries that have abol-

ished the death penalty show that the absence of the death penalty

has not resulted in an increase in serious crime.

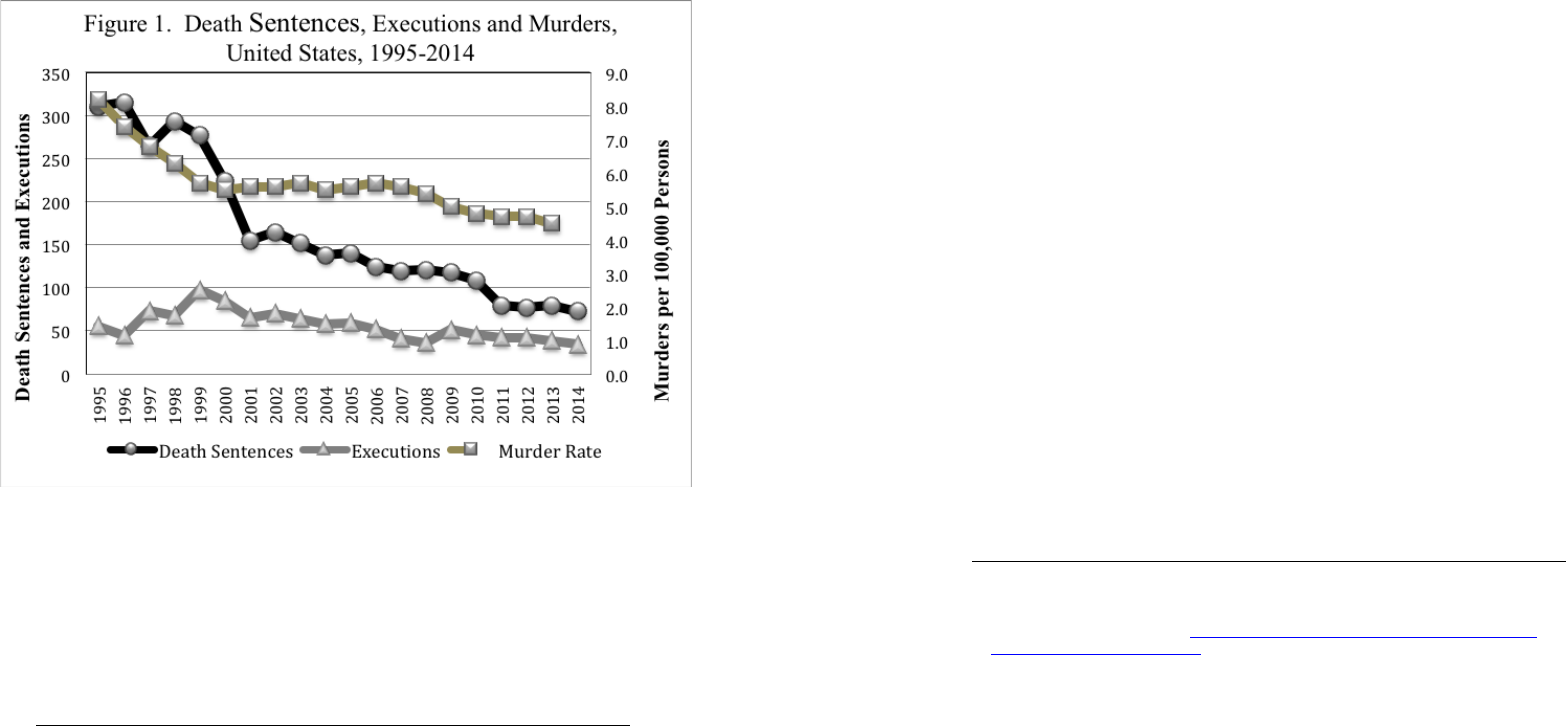

In 2012, research from the US-based National Research Council

conrmed the United Nations report’s conclusions: “Research to

date on the eect of capital punishment on homicide is not informa-

tive about whether capital punishment decreases, increases or has no

eect on homicide rates.”

11

Recent US government statistics conrm

the lack of supporting evidence for the deterrent eect of capital

punishment.

12

10 Roger Hood, The Death Penalty—A Worldwide Perspective (Clarendon Press, 1996), p.238. The

fth edition of this book, co-authored by Carolyn Hoyle and Roger Hood, who have also

contributed to this volume, was published in 2015.

11 National Research Council, Deterrence and the Death Penalty (Washington, DC, National Acade-

mies Press, 2012).

12 According to the U.S. Department of Justice’s annual FBI uniform crime report for 2012, the

national murder rate remained approximately the same in 2012 as in 2011. The northeast, the

region with the fewest executions, had the lowest murder rate of any region, and its murder

rate decreased 3.4 per cent from the previous year. The south, which carries out the most ex-

ecutions of any region, again had the highest murder rate in 2012. U.S. Department of Justice,

Crime in the United States, 2012 (Washington, DC, 2013).

The book consists of six chapters. The rst three chapters are dedi-

cated to the three issues identied at our initial 2012 panel as decisive

for decision-making on moving away from the death penalty and

on which we held individual panels in 2013 and 2014: wrongful

convictions (chapter 1), the myth of deterrence (chapter 2) and

discrimination (chapter 3). They were supplemented with three

additional chapters, covering other issues highly relevant to decisions

about the death penalty. Values related to the sanctity of life and the

limits of state power are discussed in chapter 4. Chapter 5 deals with

the role of leadership in moving away from the death penalty. Chap-

ter 6, looking forward, provides data and examines trends.

Chapter 1 addresses wrongful convictions from the personal perspec-

tives of a wrongfully convicted person, an academic, a civil society

activist and a former prosecutor. It is not easy for governments and

leading representatives of justice systems to acknowledge that, despite

heavy investment in the legal process, wrongful convictions occur. It

is even more alarming that they occur in death penalty cases, includ-

ing in the most sophisticated justice systems.

DNA test results have conrmed long-standing warnings by aca-

demia and civil society in this regard. In the United States, the rst

country to use post-conviction genetic testing on a large scale, 140

death row inmates have been exonerated since the 1970s.

9

Had public pressure to identify and punish perpetrators made wrongful

convictions more likely in the murder and rape cases for which exoner-

ating DNA evidence became available? Wouldn’t similar pressure have

occurred in other serious crimes in which such a test was not possible?

If this is a problem in advanced industrial countries, with well-re-

sourced legal systems, what about those with less sophisticated legal

systems with fewer safeguards, opportunities for review and resources?

It is clear that wrongful convictions do occur and that it is unacceptable

for them to end in execution. The death penalty is simply too nal,

given the imperfections of even the most sophisticated legal systems.

9 For an analysis of some of their cases, see Brandon L. Garrett, Convicting the Innocent (Cambridge,

Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, 2011). The Innocence Project, founded by Barry Scheck

and Peter Neufeld at Cardozo Law School in 1992, has done signicant work on exonerations.

Gradually it evolved and involved many other people and institutions in identifying and freeing

the wrongfully convicted. See www.innocenceproject.org; see also Garrett’s article in this book.

14 15

should there not be more questioning of individual guilt and mitigat-

ing circumstances of alleged perpetrators belonging to marginalised

groups, instead of discrimination against them?

Besides the three main issues relevant for abolition or retention of

the death penalty, around which the rst three chapters of this book

are organised, there are many other issues. The economic eect of the

death penalty is one of them.

In various circumstances, this

may be astonishingly dierent.

I was present at a meeting

during which the top United

Nations ocial, speaking to

the leader of a developing

country that carried out fre-

quent executions after legal

proceedings that were considerably below international standards,

pleaded for abolition or at least a moratorium on executions. “I have

no money to feed them or build them prisons,” the leader responded;

“a bullet is cheaper. But if you want them,” he added, “you can take

them back with you to New York.”

International norms are clear that if the death penalty exists, those

facing it should be aorded special protection and guarantees to

ensure a fair trial, above and beyond the guarantees aorded to defen-

dants in non-capital cases. This creates a paradox. The death penalty

is cheaper than other forms of punishment only if its execution does

not require complex legal proceedings or safeguards, such as the use

of forensics and reviews. However, in such cases the likelihood of

wrongful conviction is exacerbated. But if the number of safeguards

is increased, the death penalty becomes the most expensive form of

punishment, as the bulk of US research clearly indicates.

15

In fact, the cost of the death penalty is so much higher than the cost

of a life sentence without parole that abolitionists, especially in the

United States, use this argument in their campaigns.

16

Even when the

15 For a summary of these studies, see Rudolph J. Gerber and John M. Johnson, The Top 10 Death

Penalty Myths (Westport, Connecticut, Praeger, 2007), pp. 165-171.

16 See Death Penalty Information Center, Smart on Crime: Reconsidering the Death Penalty in a Time

of Economic Crisis (Washington, DC, 2009).

Most justice systems, in deciding guilt, accept the ethical principle

in dubio pro reo (when in doubt, [decide] for the accused). By way of

analogy, if there is no proof that the death penalty deters crime, why

would we continue to apply it? It may be out of ignorance, or deter-

rence may be a g leaf covering other motives: the desire for talionic

revenge,

13

or to protect dominant social groups and their interests; in

most retentionist states the death penalty disproportionately aects

socially marginalised groups—migrants, racial and ethnic minorities,

the poor and people with mental disabilities—some of them victims

of compounded discrimination.

Chapter 3 raises concern over the disproportionate eects of the death

penalty on marginalised groups in Africa, the Caribbean, India and

the United States. Marginalised groups are overrepresented among

the wrongfully convicted to a disturbing extent.

14

People with a

mental disability or without a competent defence lawyer are more

vulnerable to pressure to make a false confession, and jurors may be

more prone to suspect a defendant who is dierent from them. Also,

in too many legal systems, nancial resources, or the lack thereof,

determine the quality of legal representation.

From a moral perspective, the attitude and response to crimes

committed by members of marginalised groups should not be to dis-

criminate against them further, but precisely the opposite: to look for

mitigating circumstances, which may have been a consequence of the

discrimination they have been subjected to.

There needs to be some soul-searching and recognition of responsi-

bility on the part of society, when members of marginalised groups

are involved in crimes. To what extent have discrimination and unjust

treatment of members of racial or ethnic minorities contributed to

the commission of crime? How has a life of deprivation and lack of

opportunity for the poor, uneducated or mentally disabled contributed

to the commission of their crimes? From the perspective of justice,

13 Talion, or lex talionis in Latin, is a principle that perpetrators should receive as punishment the

same injuries that they inicted upon their victims. Its origins can be traced to early Babylo-

nian law, which subsequently inuenced Biblical and early Roman views on punishment. It is

also reected in later (including some current) justications of corporal punishment.

14 See Brandon L. Garrett, Convicting the Innocent (Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University

Press, 2011), p. 235.

“THE EVOLUTION OF

HUMAN RIGHTS HAS

REDUCED STATE SOVER

-

EIGNTY IN MANY AREAS;

THE DEATH PENALTY SHOULD

BE ONE OF THEM AS WELL.”

—Ivan Šimonovi´c

16 17

It is also questionable whether, in practice, the death penalty helps

provide closure, as it is so often argued. In most retentionist states

it is gradually being reduced in scope to exclude minors, pregnant

woman, people with mental disabilities and many others. For example,

in the United States, prosecutors seek the death penalty in only about

2 per cent of intentional homicide cases, and the death sentence is

imposed in only about half of those. Of those death sentences, about

two-thirds are reversed on appeal. In the end, just about one-third of

1 per cent are executed, and this after an average delay of 12 years.

18

Does the possibility of the death penalty psychologically prevent clo-

sure and healing—could these in fact come much sooner in cases that

result in a long prison term or a life sentence without the possibility

of parole? Does not the frustration of waiting in vain for a perpetrator

to be executed not actually hurt those seeking revenge more than if

there was no death penalty at all?

Are juries more reluctant to nd defendants guilty if there is a chance

that they might be executed? Does that lead to more acquittals and

thus hurt victims and their families even more when they see suspects

go free? Furthermore, does the death penalty aect other innocent

third parties more than other penalties? Do families of convicts suer

more because of the prolonged death threat to their loved ones?

19

May some of them not also be perceived as victims?

Although the analysis of the social, economic and psychological eects

of the death penalty clearly indicates its harmful eects, it can also be

attacked in a Kantian moral safe-haven, detached from any measurable

social eect and scientic evidence. In my view, the essence of the

moral opposition to the death penalty is the argument that killing is

simply wrong, whether we relate it doctrinally to a human right to life

and the right not be subjected to cruel or inhuman punishment, or not.

No one can blame victims and their families for wanting revenge,

including through the death penalty. In their pain and loss, they are

entitled to that desire. However, laws exist to prevent individuals from

18 Gerber and Johnson, The Top 10 Death Penalty Myths, pp. 196-197 and 222.

19 Psychiatrists warn that many family members, especially those who were the primary support

of a capital defendant, experience depression and symptoms associated with post-traumatic

stress disorder.

majority of public opinion polls indicate support for the death pen-

alty, when confronted with nancial analysis that indicates that a life

sentence without parole could produce savings that could instead go

towards compensation of victims and their families, public opinion

often tends to sway in favour of the latter option.

On the other end of the scale from the pragmatic approach are the

moral and value-based arguments regarding the death penalty. Chap-

ter 4 addresses the relationship between the death penalty and values

through an article reecting a victim’s perspective, two articles that

are potentially controversial, as is so often the case when values are

concerned—one dealing with major religious doctrine and the other

with politics, as well as two articles assessing the death penalty from

the perspective of international human rights obligations

Despite the lack of evidence of deterrence, retentionist’ arguments

can be articulated and are indeed perceived by some as moral ones.

Essentially, the reasoning is based on a “just retribution” argument—

changing the perspective from utilitarian to Kantian. If crime deserves

adequate punishment for moral reasons, it makes social consequences

and the deterrent eect (or lack thereof) less relevant. Furthermore,

even if capital punishment has negative social consequences, it should

be retained because it is proportionate to some crimes—vivat iustitia,

pereat mundus (justice should live even if the world were to die).

When discussing the death penalty from the perspective of values,

it is critical to bring the victims’ perspectives into the debate. Their

position certainly carries important moral and political leverage.

However, those perspectives at times seem to be quite dierent. Some

family members of murder victims are among the strongest support-

ers of the death penalty, well organized and inuential. But others are

equally strongly convinced that murder cannot be countered with

murder. They do not want the lives of their loved ones to be avenged

with more violence, and instead of focusing on retribution, they try

to set themselves free from their trauma through forgiveness, healing

and restoration.

17

17 In the United States they have formed an association called Murder Victims’ Families for Rec-

onciliation. Membership requirements are that a close family member has been murdered and

that they oppose the death penalty. Some of their stories have been collected in Rachel King,

Don’t Kill in Our Names (Rutgers University Press, 2003).

18 19

21st century, the right to take another person’s life is no longer a part

of the social contract between citizens and the state. The time when

Rousseau reluctantly accepted such a sacrice as a part of the social con-

tract, necessary to keep peace in society, has long gone. Locke believed

that political power includes the right to pass laws that carry the death

penalty. Not anymore. The evolution of human rights has reduced state

sovereignty in many areas; the death penalty should be one of them.

But what about public opinion and democracy and the “popular sov-

ereignty” argument in many countries, where the majority is in favour

of the death penalty?

22

Even when that is the case, it does not preclude

intellectual and political leaders’ responsibility to push for abolition. Is

it not precisely the role of leadership to inuence society to become

more moral? Instead of “killing for votes” and death-penalty populism,

is it not their duty to share with their people relevant information, that

they may not be aware of, and help change mind-sets and attitudes?

23

Chapter 5 highlights the importance of leadership in moving away

from the death penalty. To stand for abolition or even for moratorium is

often not popular. To change the tide requires courageous and commit-

ted leadership and a successful information campaign. Contributions

in this chapter are provided by international leaders and heads of state

and government from dierent cultures, continents and backgrounds,

each of whom contributed to moving away from the death penalty

nationally and internationally. The chapter also includes an article on

the relevance of public messaging and information sharing for inu-

encing popular attitudes towards the death penalty and its abolition.

Every book, including this one, should have a conclusion or a for-

ward-looking ending. Chapter 6 of the book includes a contribution

by the secretary-general of Amnesty International dealing with statis-

tics and trends in moving away from the death penalty.

22 Perhaps a little exaggerated, but with a point: “The people who know the least about how

the system of death sentencing functions appear to be the ones who support it most”—Craig

Haney, Death by Design: Capital Punishment as a Social Psychological System (New York, Oxford

University Press, 2005), p. 219. The lack of information-sharing on the death penalty is espe-

cially drastic in Japan, a retentionist country with strong public support for the death penalty,

which provides no ocial information on how many people are on death row, how and when

sentenced people are selected for execution or what the costs are for the death penalty com-

pared with the alternative punishment (see the contributions by Hoyle and Hood and Mai Sato

to this volume as well as Sato’s book The Death Penalty in Japan, Will the Public Tolerate Abolition?

(Wiesbaden, Springer, 2014).

23 See Sato, The Death Penalty in Japan.

pursuing vengeance and their own vision of justice. If they do anyway

(if, for example, a victim kills a perpetrator) then they become per-

petrators and pay the price, both legally and morally. Although we

may feel empathy with such a victim seeking revenge, Nietzsche’s

warning—that when ghting monsters you must take care not to

become one yourself—should be remembered. Killing by the state is

wrong as well, potentially even worse than killing by an individual.

Individuals can sometimes kill in self-defence; states have such a range

of options for protecting people from a threatening individual that

killing is disproportionate to the danger that person represents. An

individual might kill out of passion or be criminally insane. The state,

when administering the death penalty, always kills after reection,

fully aware and accepting of the consequences.

An individual who kills, whether brought to justice or not, at least

pays for the violation of a fundamental moral rule through his or her

guilty conscience. When a state kills, it kills through its ocials, with-

out a guilty conscience; executioners are just doing their job.

20

There

is a tendency, especially in the developed retentionist countries, to

carry out the death penalty in an increasingly organized, technical and

bureaucratic manner, favouring teamwork and a piecemeal approach,

without thorough reection, emotion or individual responsibility.

21

Is it acceptable that killing takes place without anyone being morally

responsible for it? Is a state that kills a dangerous state? Can its right

to kill be misused against enemies of the state or enemies of those in

power? Is such a state, in essence, more prone to also violate other

human rights? If a state can kill, can it also torture when it is deemed

necessary—also without guilt on the part of the decision-makers,

through professional torturers doing their job? Can it send its citizens

to kill and be killed in war, not in self-defence but for some other

important “national interest”?

The death penalty, and the prerogative of the state to impose and execute

it, is related to our approach to contemporary state sovereignty. In the

20 In If This Is a Man (Collier Books, 1993), writing about Auschwitz, Primo Levi expressed

profound amazement: “How can one hit a man without anger?” In a similar moral sense should

not we ask ourselves how one can kill without guilt?

21 See Linda Ross Meyer, “The meaning of death, last words, last meals”, in Who Deserves to Die?

Constructing the Executable Subject, Austin Sarat and Karl Shoemaker, eds. (Amherst, University of

Massachusetts Press, 2011).

20 21

• The use of the death penalty should no longer be perceived

as an entitlement of a sovereign state, because it violates

human rights. No national interest can justify human rights

violations such as the death penalty or torture. International

recognition and protection of human rights limit state powers

in this regard.

• As long as the death penalty exists, it can be misused, for exam-

ple to target particular social groups and political opponents.

This book oers solid scientic evidence that supports abolition of

the death penalty. Although it is an advocacy book, mostly written

and edited by committed abolitionists, it clearly distinguishes between

facts and values. I encourage you to choose your stand on this issue

based on solid information.

I believe that one day, people will look back and wonder how it

was possible that the death penalty ever existed—just like, in most

societies today, it is already hard to understand how public executions

could ever have taken place. But when will it become universally

accepted that the death penalty violates the most fundamental human

right, the right to life? When will the day come when all states are

abolitionist—when there is no death penalty anywhere, anymore?

If we were to extrapolate a curve based on current trends—reduction

of the number of crimes punishable by death, moratoria on its exe-

cution, and full abolition—one could perhaps predict the number of

years it may take. But of course, in society, where human action can

change trends, such predictions are highly unreliable.

This is the main reason for publishing this book: it is a part of global

action to encourage global abolition of the death penalty. State power

has to have its limits, limits that uphold human rights.

Ivan Šimonovi´c

Assistant Secretary-General for Human Rights

New York, 31 August 2015

Let me contribute to the tracing of the way forward in moving away

from the death penalty by summarizing the arguments against it and

encouraging political and social leaders to act decisively towards

its abolition.

In my view, the death penalty is morally, socially and politically

wrong. Morally, killing is wrong. Killing on behalf of a state is wrong

as well. Some may believe that the death penalty is a just and moral

punishment for the most serious of crimes; victims and their families

are morally entitled to long for revenge. However, the social, political

and economic costs of such retribution are, in my opinion, too high:

• Despite the greatest judicial eorts, wrongful convictions are

not avoidable. Capital punishment is simply too nal and

irrevocable, and makes it impossible to correct such mistakes.

The consequences for human error are too grave.

• There is no conclusive empirical evidence that the death

penalty deters crime.

• The death penalty is cheap only if it is carried out quickly.

Putting in place the necessary safeguards to prevent wrongful

convictions often makes legal proceedings lengthy and much

more costly than the longest prison sentence.

• Long delays on death row make the death penalty a cruel

punishment, unacceptable from a human rights perspective.

• Long delays in carrying out executions also postpone closure

and psychological healing for victims and their families, in a

way that (for example) the perpetrator’s return to prison to

begin a life sentence without parole does not.

• Not all victims’ families support the death penalty, and even

among those who do, and who desire revenge or closure

through it, the great majority are left frustrated because only

a small minority of perpetrators are executed.

• The death penalty is not imposed in a just and equal way.

Those sacriced on the altar of retributive justice are almost

always those who are vulnerable because of poverty, minority

status or mental disability.

22

“If a great country cannot ensure

that it won’t kill an innocent citizen,

it shouldn’t kill at all.”

— Kirk Bloodsworth

23

CHAPTER 1

WRONGFUL CONVICTIONS

Chapter includes articles by an exoneree, an academic, a former prosecutor and an

activist for global abolition of the death penalty. Each of them oers a dierent

perspective. Their ndings converge on this point: there are a signicant number

of wrongful convictions, including in capital punishment cases, and executing the

innocent is simply not acceptable.

Kirk Bloodsworth was the rst person in the United States to be exonerated—

have his conviction reversed—through DNA testing. He was a young man, a

former marine from a humble background, without any criminal record, when

he became the victim of faulty eyewitness identication. After almost nine years

(two of them on death row) trying to prove his innocence, he was nally released.

Nowadays, he is a strong advocate for the abolition of the death penalty and for

the rights of the wrongfully convicted.

Brandon Garrett, an academic who does legal research on wrongful convictions,

their causes and ways to prevent them, analyses DNA-based exonerations in

the United States with particular attention to death penalty cases. He documents

how revelations about innocent people being sent to death row have permanently

altered the death penalty debate in the United States. In his view, jurisdictions in

other countries should similarly take note of the possibility of wrongful convictions.

Gil Garcetti is a convert. He served as a district attorney in Los Angeles County,

California, for many years and sometimes sought the death penalty for those he

prosecuted. However, the death penalty’s disproportionate eect on minorities and

the history of wrongful convictions led him to become an abolitionist. He had a

major role in the Proposition 34 campaign in California, which almost succeeded

in replacing the death penalty with life imprisonment without parole (it attracted

48 per cent of the vote).

Saul Lehrfreund discusses retentionist countries across the Caribbean, Africa and

Asia in which law and practice do not provide the protections in capital punish-

ment cases that are required by international human rights law. He concludes that

miscarriages of justice and executions of the innocent may occur in every system

and that this is a major reason that an increasing number of countries have moved

away from the death penalty.

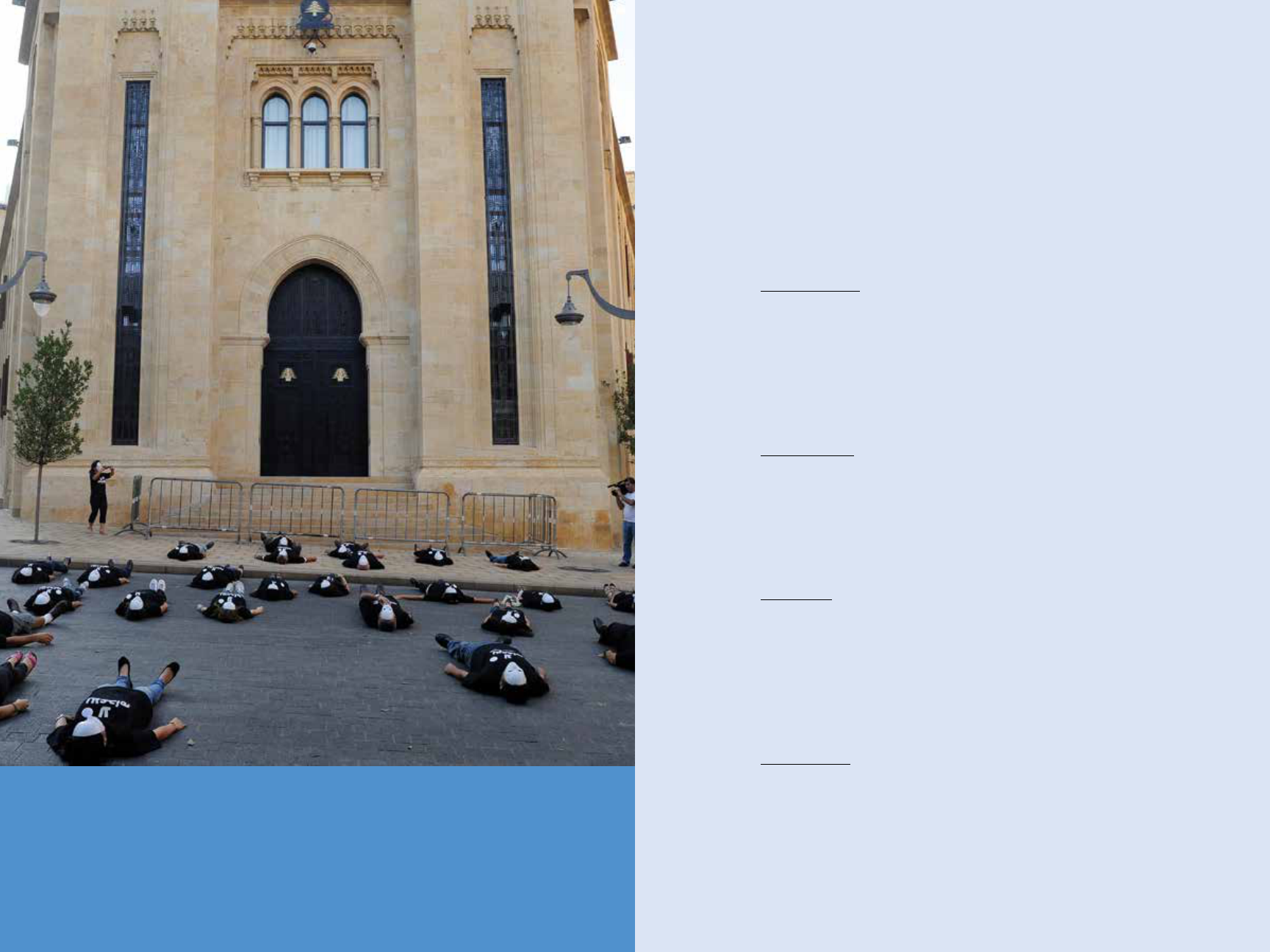

Activists lie on the street to mark the World Day against the Death Penalty. / © EPA/Wael Hamzeh

24 25

WITHOUT DNA EVIDENCE,

I’D STILL BE BEHIND BARS

Kirk Noble Bloodsworth

1

I am the rst person in the United States to be exonerated from a

capital conviction through DNA testing. When I was exonerated in

1993, I had spent 8 years, 11 months, and 19 days (including two years

on death row) for a crime I did not commit. I am living proof that

America’s system of capital punishment is broken beyond repair.

In early 1984, before my life changed forever, I was just a humble

waterman living in Cambridge, Maryland. I was barely 23 years old,

newly married, and had just served four years in the US Marine

Corps. I had never been arrested in my life. This all changed on

August 9, 1984, when the police knocked on my door at 3 o’clock

in the morning and arrested me for the murder of Dawn Hamilton.

In a matter of days, I became the most hated man in Maryland.

How was I, a former US Marine with no criminal record and no

connection to the scene of the crime, convicted and sentenced to

death for a murder I didn’t commit?

On July 25, 1984, 9-year-old Dawn Hamilton was tragically raped

and murdered in Baltimore County. She was playing outside with a

friend in the morning when she came across two little boys shing

at a pond. A man nearby approached Dawn and oered to help

her nd her friend in their game of hide-and-seek. That was the

last time Dawn was seen alive. Her body was found in the park

that afternoon, and the evidence of the brutal crime horried the

ocials at the scene.

Because of the notoriety of the crime, the police were understandably

eager to nd Dawn’s killer and ease the community’s fear. When the

police department found the two little boys who had seen the suspect,

the ocers drafted a composite sketch of the man they were looking for.

1 Kirk Noble Bloodsworth, victim of wrongful conviction.

The witnesses described the suspect as 6 feet 5 inches tall, with a slim

build and dirty blond hair.

At the time of the investigation, I was 6 feet tall, with a thick waist,

ery red hair and long, noticeable sideburns.

Despite the fact that I did not t the description, an anonymous

caller suggested my name to the Cambridge Police Department. In

a poorly conducted police line-up, I was identied as the last man to

be seen with the victim.

Eyewitness misidentication is widely recognized as a leading cause

of wrongful convictions in the United States. Since 1989, DNA evi-

dence has been used to exonerate over 200 individuals, and about 75

per cent of these cases involved inaccurate eyewitness identication.

Other faulty police procedures played a role in my wrongful conviction.

I went to the police station voluntarily. Knowing that I was inno-

cent of this crime, I wanted to be as cooperative as possible. When I

entered the interview room, a pair of girl’s panties and a rock were

lying on the table. I was never told why. I later found out that the

items were part of an experiment that the police devised because they

believed that the killer would have a strong reaction to these items

related to the crime. I had no reaction. But after I left the station, I

talked to my friends about what the police had done. During the

trial, the police used these statements against me, claiming that I knew

something that only the killer would know. I only knew because they

had shown the items to me that day.

There was no physical evidence against me. I was convicted primar-

ily on the testimony of ve eyewitnesses who were later shown to

be terribly mistaken. With all the fear and anger in the community

surrounding Dawn’s murder, it took the jury less than three hours to

convict. I was sentenced to die in Maryland’s gas chamber. When my

death sentence was announced, the courtroom erupted in applause.

I, an innocent man, was sent to one of the worst prisons in the United

States at the time, the Maryland State Penitentiary. There was not a

26 27

day that passed that I didn’t try to tell someone I was innocent of

this crime. But, as a guard at the penitentiary told me during my rst

week, “Everyone in the pen is innocent, man, don’t you know?” No

one believed me.

Life at the Maryland State Penitentiary can only be described as hell on

Earth. I still have nightmares about it. Imagine living in a cell where you

can only take three steps from the back wall to the front door. I could

touch the side walls with my outstretched arms. My cell was directly

under the gas chamber where I was sentenced to die at the hands of the

state. The guards thought it was funny to remind me of that fact. They

would describe the entire procedure in detail and laugh at my fate.

Fortunately, I only had to spend two years dreading this death. A

second trial reduced my punishment to back-to-back life sentences.

I spent many of my

years in the peniten-

tiary in the infamous

South Wing, where

men were driven mad

by the prison brawls, lth, and other horric experiences. Prisoners

kept cotton balls in their ears at night so cockroaches wouldn’t lay

eggs in their heads. Prisoners would scream all through the night. The

conditions proved even worse for me, as I was jeered by the other

prisoners as a child rapist and killer. I had to lift weights every day

and adopt a rough demeanour in order to fend o constant threats.

While I fought to stay safe at the penitentiary, I spent most of my time

ghting to prove my innocence to anyone who would listen. I signed

every letter I sent “Kirk Bloodsworth A.I.M., An Innocent Man.”

While writing countless letters to advocates, I resolved to advocate

for myself through my own research. I spent long days in the prison

library, reading every book I could get my hands on. The key to my

freedom came in the form of a book titled The Blooding by Joseph

Wambaugh. This book chronicled the rst time a process called DNA

testing was used to solve a series of homicides in England. I had an

epiphany right there: “If it can convict you, it can free you.”

At the time of my rst trial, DNA testing was not a well-understood

concept in criminal law. But when I came across this book in 1992,

DNA testing in criminal cases was breaking ground. My attorney, Bob

Morin, submitted a request for the evidence in my case to be tested

in a lab. The prosecutor in the case almost brought my innocence

claim to a halt when she sent a letter with a devastating message: The

biological material in my case had been inadvertently destroyed.

But by the grace of God, the judge from my second trial had decided

to store some of the physical evidence in his chambers. I cannot say

for sure why he decided to do that, but I have a hunch that he knew

there was more truth to be told.

One day in 1993, the truth came out. I received a phone call from

my typically mild-mannered attorney. He couldn’t contain his excite-

ment. The sperm stain lifted from the victim’s underpants did not

match my DNA. The DNA told the truth; I was not guilty of this

crime. The appeals process in capital cases can be complicated and

hard to manoeuvre. I was fortunate to have supportive family, advo-

cates and an attorney who believed in my innocence.

Had evidence for DNA testing not been available, I would still be

in prison today. In the vast majority of criminal cases in the United

States, DNA or other biological evidence is not available—like in the

cases of Troy Davis and Carlos DeLuna, who were executed despite

grave doubts about their guilt. It is dicult to overturn wrongful

convictions without evidence to test. Unfortunately, it is more than

likely that there are people sitting on death row right now who are

in this tragic bind.

It is hard to know just how I sustained hope through this ordeal.

One story in particular comes to mind. Three months before the

results came back that would prove my innocence, I lost my mother.

She died of a heart attack on January 20, 1993. I was escorted to

the funeral home in shackles and handcus and was only given ve

minutes with my mother. This was the woman who had taught me

that if I don’t stand up for something, I would fall for anything.

She always believed in my innocence, but she didn’t live to see

me vindicated.

“IF WE KILL ONE INNOCENT

MAN, IT’S ONE TOO MANY.”

—

Kirk Noble Bloodsworth

28 29

Finally, on June 28, 1993, I walked out of the Maryland State Peni-

tentiary a free man.

Even today, many exonerees nd it hard to shake the stigma after

they are released from prison. At the time of my DNA exoneration,

the technology was still new and the public wasn’t sure if I could

be trusted. When I returned to Cambridge, Maryland, I had trouble

getting a job and I was harassed by my neighbours.

It didn’t help that the prosecutor, Ann Brobst, would not admit the

state’s mistake. Even when I was released based on clear scientic

evidence, Brodst stated, “If we had the DNA evidence in 1984, Mr.

Bloodsworth would not have been prosecuted, but we are not pre-

pared to say he is innocent.”

Unfortunately, it would take 10 years for Dawn’s true killer to be iden-

tied. I received a phone call from Brobst in September 2003 when

the state of Maryland nally found a match in the DNA database.

The murderer was identied as Kimberley Shay Runer. Not only

was his name given in a tip at the time of the original investigation,

but Runer was a suspect in rapes in the Fells Point neighbourhood

of Baltimore. He was serving time for attempted rape when the DNA

match was concluded years later.

As fate would have it, Runer had been sleeping in the cell below

me in the Maryland Penitentiary all these years. We had lifted weights

together. I gave him library books. He never said a word in all that time.

When I was exonerated, the state of Maryland paid me $300,000 for

lost income during the time I was wrongfully imprisoned. But I lost

so much more than money in those eight years that I will never get

back. While I grieve this loss, I am no longer angry, and for the past

decade of my life, I have simply wanted to do something to ensure

that no-one else suers what I did. After all, if it can happen to me, it

can happen to anyone.

This principle guides my work today. During my years of freedom, I

have fought for wrongfully convicted people all over the United States

and lobbied for reforms to the American criminal justice system, such

as the Innocence Protection Act of 2003, which includes the Kirk

Bloodsworth Post-Conviction DNA Testing program, providing fed-

eral funds to states for DNA testing for prisoners who claim their

innocence. I have become one of many exonerees who, with the

help of great advocacy organizations like Witness to Innocence, travel

around the country to share our cautionary tales.

When I tell young students my story, they always say the same thing:

I can’t believe this could happen in America.

While people are concerned by the rate of wrongful conviction in

the United States, sometimes it takes a personal story to put a real face

to the issue. Now, I respectfully submit my story to you. This story is

why I believe that the time is overdue for the United States to follow

the lead of our partners in the international community and abolish

the death penalty once and for all.

Make no mistake about it. I am not here because the system worked. I

am here because a series of miracles led to my exoneration. Not every

person wrongfully convicted of a capital crime is as blessed. If we kill

one innocent man, it’s one too many.

I certainly understand the anger and desire for justice in capital cases.

When I speak at death penalty events, I sometimes carry with me the

picture of the victim Dawn Hamilton. Her death was so horric that

it still moves me to tears. But the great US Supreme Court Justice

Thurgood Marshall one said, “The measure of a country’s greatness

is its ability to retain compassion in time of crisis.” Even in the midst

of fear and anger, a great country must ensure that its criminal justice

system is eective and accurate. If a great country cannot ensure that

it won’t kill an innocent citizen, it shouldn’t kill at all.

For these reasons, I strongly believe that abolishing the death penalty

is a necessary step for the integrity of the criminal justice system in

the United States and other nations.

30 31

DNA EVIDENCE CASTS LIGHT

ON FLAWS IN SYSTEM

Brandon L. Garrett

1

In no country other than the United States has there been such a large

group of people whose innocence has been clearly proven by DNA

tests years after their conviction. This group of innocent people, called

DNA exonerees, provides a unique opportunity to learn about what

can go wrong in even the most serious criminal cases. Exoneration is

an ocial decision to reverse a conviction based on new evidence of

innocence. The most haunting feature of many wrongful convictions

is that they can come to light by sheer fortuity. We may never know

how many other innocent people have been convicted and punished,

even for serious crimes like murder.

Accuracy may be of particular concern for very serious but di-

cult-to-solve crimes like murder, in which the death penalty may

be charged. If the culprit is not caught in the act, police may need

to rely on eyewitnesses, forensics or confessions—evidence that they

can get wrong, due to missteps and unsound practices early in crim-

inal investigations. Once key evidence is contaminated during an

investigation, it may be very dicult for subsequent trial, appeals,

and post-conviction courts to detect, much less correct, the errors.

What I found disturbing when reading a large set of criminal trials

of DNA exonerees is that a case against an innocent person may not

seem weak at the time; it may seem uncannily strong. Where very

few cases can be tested using DNA, it is crucial to prevent wrongful

convictions before it is too late.

Over 140 death row inmates have been exonerated since the 1970s

in the United States.

2

I focused on a small group of those cases when

1 Brandon L. Garrett is a professor ar the University of Virginia School of Law.

2 As of this writing, the Death Penalty Information Center had a count of 144 death-row

inmates who have been exonerated <www.deathpenaltyinfo.org/innocence-list-those-freed-

death-row>. A 2008 study modelled a false conviction rate by examining exonerations in cap-

ital cases in published work and in a work in progress. Samuel R. Gross and Barbara O’Brien,

“Frequency and predictors of false conviction: Why we know so little, and new data on capital

cases”,

Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, vol. 5 (2008), pp. 927 .

I examined what happened in the rst 250 DNA exonerations in

my 2011 book Convicting the Innocent: Where Criminal Prosecutions Go

Wrong.

3

There have now been more than 300 such exonerations in

the United States. Of the rst 300 cases, 192 were convicted of rape,

68 of rape and murder, 32 of murder, and 8 of other crimes; 18 had

been sentenced to death.

4

Of those 18, 16 had been convicted of rape and murder and 2 of

murder alone. The evidence in those cases relied heavily on confessions,

which we now know to have been false, and a range of awed forensic

evidence. Eight involved detailed false confessions allegedly including

inside information that only the murderer could have known. With the

benet of DNA tests, we now know those people were innocent, but

they may have seemed quite guilty at the time. Absent a complete video

recording of the interrogations, jurors readily believed law enforcement

ocials’ accounts of the confessions. Three of these confessions were

made by mentally disabled people who could be expected to have been

highly vulnerable to police coercion and suggestion.

5

Ten of the cases involved testimony by informants, including seven

jailhouse informants, three witnesses who testied in cooperation

with prosecutors, and two codefendants who alleged they were

accomplices but who were also innocent and themselves wrongly

convicted. These informants also claimed to have overheard, in jail

or elsewhere, details that only the killer could have known. Perhaps

the most chilling of those cases is that of Ron Williamson and Dennis

Fritz, in which the witness testifying for the state at trial, and describ-

ing the victim having a last dance with Williamson, was later shown

by DNA testing to himself have been the killer.

Eight cases involved identications by eyewitnesses, sometimes mul-

tiple eyewitnesses, who were all mistaken about what they had seen.

3 Data from that research are available online at <www.law.virginia.edu/html/librarysite/garrett_

innocent.htm>. A multimedia online resource about these data and ways to prevent wrongful

convictions is available at <www.innocenceproject.org/Content/Getting_it_Right.php>.

4 My book examined 17 such DNA exonerations in capital cases; in 2012, Damon Thibodeaux

became the 300th DNA exoneree and the 18th death row DNA exoneree in the United States.

Douglas A. Blackmon, “Louisiana death-row inmate Damon Thibodeaux exonerated with

DNA evidence”,

Washington Post, 28 September 2012.

5 The US Supreme Court noted the existence of one such case, that of Earl Washington Jr., in its

decision in

Atkins v. Virginia, 536 U.S. 304, 320 n. 5 (2002).

32 33

Fourteen cases involved forensic evidence, including a number with

unreliable and unvalidated forensics. Ten of the cases involved hair

comparisons, two involved bre comparisons and nine involved

blood typing. Two involved bite mark comparisons; perhaps most

well known is the case of Ray Krone, who was convicted based on

little other than a awed bite-mark comparison.

The death penalty cases were not so dierent from many other DNA

exoneree cases that similarly involved murders, and in which false

confessions and informant testimony and awed forensic evidence

played a central role. Of the rst 250 DNA exonerees, 40 had falsely

confessed. I examined each of those cases in detail and found that in

all but two cases, the innocent person was said to have confessed in

detail. Those false confessions were all seemingly powerful because

they were contaminated. While many of the interrogations were

partially recorded, none was recorded in its entirety. The confessions

were concentrated in the murder cases. Of the 40 false confessions

that I studied, 25 involved rape and murder, 3 murder only, and 12

rape only.

EXONERATION: AN UPHILL BATTLE

Once evidence is contaminated early in a criminal investigation,

post-trial procedures—like appeals and the post-appeal habeas corpus

remedies that we have in the United States—may not be of much

help. It is a myth that appellate judges will correct factual errors: An

appellate court “knows no more than the jury and the trial judge” and

has a more limited role, partially because the appellate judge is “obliged

to accept the jury’s verdict” and focuses on more limited questions of

law rather than the reliability of facts.

6

An appellate judge, who was

not present at the original trial, is highly reluctant to second-guess the

jury’s decision to convict. No more than 1 or 2 per cent of cases are

ever reversed. Of course, the vast majority of criminal cases involve plea

bargains, in which the right to an appeal or post-conviction review is

usually waived. Even when an appeal can be brought, rules setting strict

time limits have traditionally prevented a convict from raising new evi-

dence of innocence (although some of those rules have been relaxed,

6 Jerome Frank and Barbara Frank, Not Guilty (Garden City, NY, Doubleday, 1957).

particularly by state statutes that permit post-conviction DNA testing),

and claims of innocence remain very dicult to make.

Once the appeal is over, an indigent inmate lacks the constitutional right

to a state-provided attorney. Every jurisdiction in the United States oers

some type of review after the appeal is complete, usually called post-con-

viction or habeas review. This additional level of review may permit, in

theory, litigation of claims that could not have been raised during the

initial appeal. However, non-death-row inmates typically do not have

lawyers to help them navigate the incredibly complex procedural barri-

ers that limit the chances of success during such reviews.

The death-row DNA exonerees typically followed a long road from

trial to exoneration. Four of them had two trials; two had three trials.

Each time they were convicted again, until they nally obtained DNA

testing and were exonerated. The picture was not much dierent for the

full group of DNA exonerees, including those who were not sentenced

to death, except that among the non-death-row prisoners, even fewer

received any relief prior to obtaining DNA testing. Non-death-row

exonerees often did not obtain lawyers after their appeal and could not

get any help ling habeas petitions. They rarely challenged the faulty

evidence that caused their wrongful convictions, and when they did try,

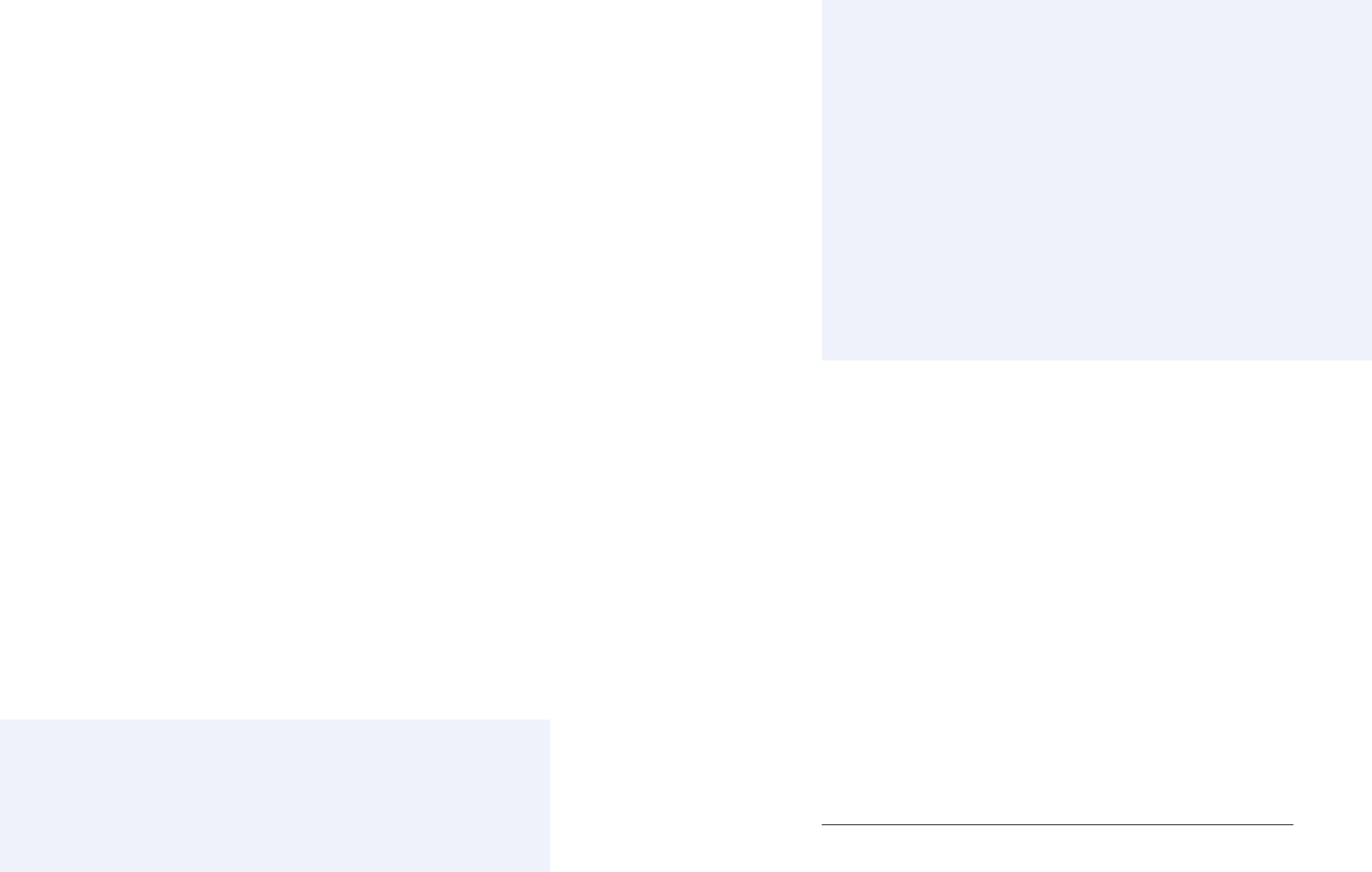

they failed. The gure that follows illustrates the degree to which the

rst 250 DNA exonerees (those who had judges write decisions in their

cases) tried to challenge the evidence presented at their trials during

appeal or post-conviction review, and how few obtained conviction

reversals before they were successfully exonerated using DNA testing.

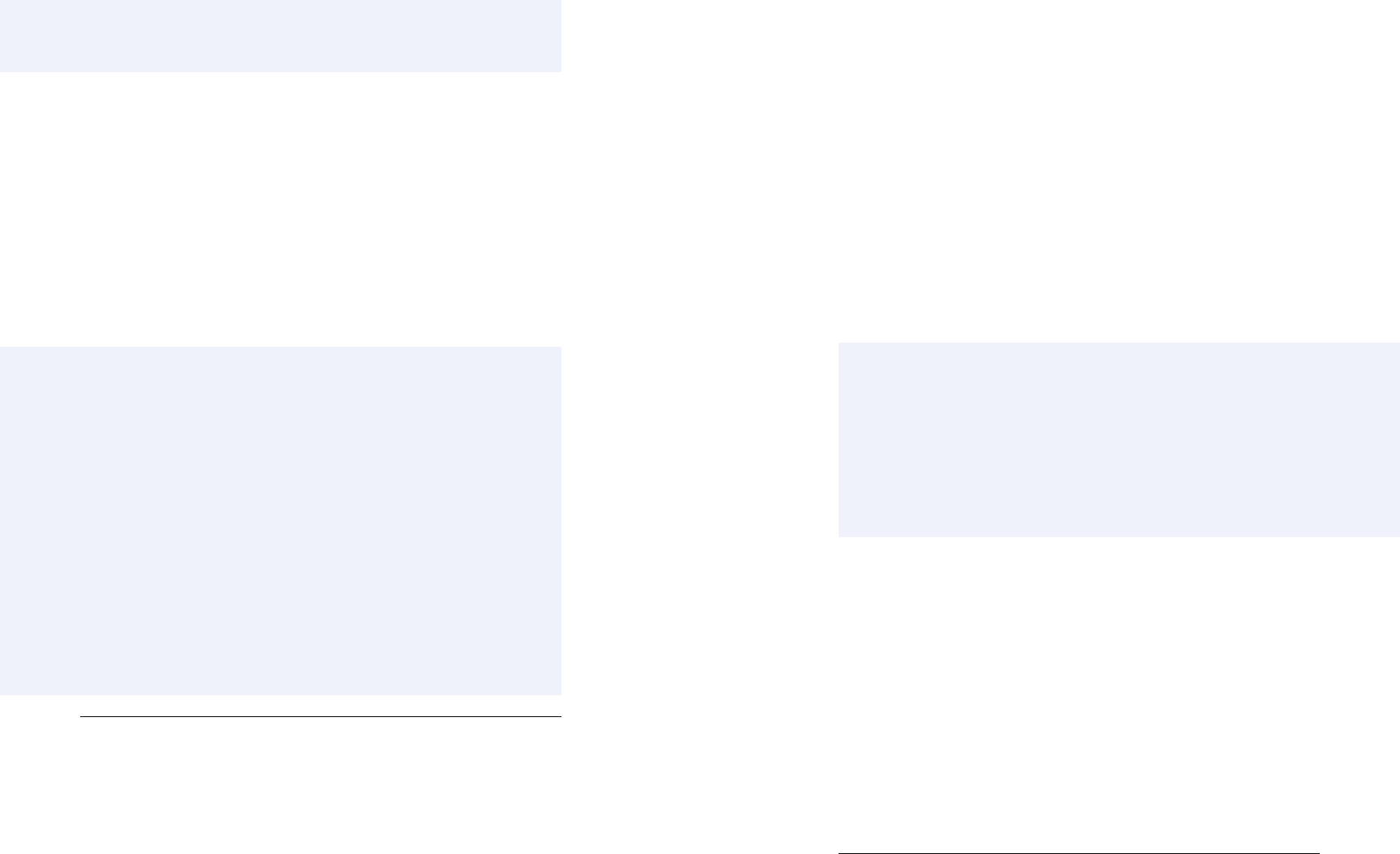

Post-conviction challenges to evidence by the

first 250 DNA exonerees

We now know that these people were innocent, but they did not have

any luck raising claims of innocence either: Every DNA exoneree who

tried to raise such a claim failed. These appeals and post-conviction

challenges took time; the road to exoneration took an average of 15

years. Of the 18 death-row DNA exonerees, 8 earned reversals on

appeal or post-conviction. This high reversal rate is consistent with

other studies of post-conviction litigation by death row inmates,

although these cases were mostly litigated before the passage of the

34 35

Antiterrorism and Eective Death Penalty Act, which now restricts

the availability of federal habeas review.

7

What is still more troubling, though, is that others were convicted

again at multiple trials, until ultimately DNA evidence set them free.

Rolando Cruz and Alejandro Hernandez each had two convictions

reversed and three criminal trials before they were exonerated. Kirk

Bloodsworth, Ray Krone, Curtis McCarty and Dennis Williams each

had two trials before they were exonerated by post-conviction DNA

testing. Innocent people can be wrongly convicted not only once but

several times, including in capital cases.

Bloodsworth was the rst person exonerated from death row in the

United States based on post-conviction DNA testing. He had been

sentenced to death for the Maryland rape and murder of a 9-year-old

girl in 1984. Five eyewitnesses had incorrectly placed him near the

crime scene. Maryland recently abolished the death penalty, in part in

response to Bloodsworth’s case.

Compare that case to the nationally and internationally well-known

Troy Davis case, a death penalty case that similarly involved a group

of eyewitnesses who had each identied Davis following eyewitness

identication procedures. Although the US Supreme Court, in a rare

move, granted a habeas petition led directly with the Court and

asked a judge to look into the new evidence of Davis’s innocence, the

Georgia Board of Pardons denied clemency, and Davis was executed

in September 2011. We will never know for sure if he was inno-

cent—there was no DNA evidence to test, or any other real forensic

evidence in the case.

8

Other prisoners have fared better, but not to the point of full exon-

eration: They have pled guilty in exchange for having their sentence

7 For a discussion of the reversal rate in capital DNA exonerations, see Brandon L. Garrett,

“Judging innocence”, Columbia Law Review, vol. 108 (2008), pp. 55 ., 99-100 (reporting a

58 per cent reversal rate, or 7 out of 12 capital DNA exonerees with written decisions). Since

that article was written, of the four additional capital DNA exonerees, Curtis McCarty received

reversals, Kennedy Brewer did not, and Michael Blair and Damon Thibodeaux did not have

reported decisions.

8 Brandon L. Garrett, “Eyes on an execution”,

Slate, September 20, 2011. For an example of an

execution that received very little attention at the time, but regarding which grave doubts have

since been raised, see James Liebman and others, “The Wrong Carlos: Anatomy of a Wrongful

Execution” (Columbia U. Press: New York, NY 2014).

reduced to time served or have received partial clemency after errors

came to light in their cases. This has occurred in high-prole cases

like those of the West Memphis Three in Arkansas, the Norfolk

Four in Virginia and Edward Lee Elmore in South Carolina.

9

There

are many more exonerations that do not involve DNA testing; very

few death penalty cases—or murder cases generally—have testable

DNA evidence.

DEBATE AND REFORM

Exonerations in capital cases have had a broad impact on the public

and policymakers and have contributed to a “new death penalty

debate.”

10

Revelations that innocent people were sent to death row

have permanently altered the debate, regardless of whether one

believes that the death penalty is justied in some circumstances.

For example, in Baze v. Rees, US Supreme Court Justice Stevens

announced his opposition to the death penalty, citing evidence from

DNA exonerations:

Given the real risk of error in this class of cases, the irrevo-

cable nature of the consequences is of decisive importance to

me. Whether or not any innocent defendants have actually

been executed, abundant evidence accumulated in recent

years has resulted in the exoneration of an unacceptable

number of defendants found guilty of capital oenses.

11

Justice John Paul Stevens, writing for the US Supreme Court in

Atkins v. Virginia, noted that “a disturbing number of inmates on

death row have been exonerated.”

12

In contrast, Justice Antonin

Scalia has argued that known exonerations represent an “insignicant

9 See “Kaine’s full statement on ‘Norfolk Four’ case”, Washington Post, 6 August 2009, available

from http://voices.washingtonpost.com/virginiapolitics/2009/08/kaines_full_statement_on_

norfo.html?sidST2009080602217; Tom Wells and Richard A. Leo,

The Wrong Guys: Murder,

False Confessions, and the Norfolk Four (New York, W. W. Norton, 2008); Raymond Bonner,

Anatomy of Injustice: A Murder Case Gone Wrong (New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 2012).

10 James Liebman, “The new death penalty debate”, Columbia Human Rights Law Review, vol.

33 (2002), pp. 527 .; Colin Starger, “Death and harmless error: A rhetorical response to judg-

ing innocence”, Columbia Law Review Sidebar, vol. 108 (February 2008), pp. 1 .

11

Baze v. Rees, 553 U.S. 35, 85-86 (2008) (Stevens, J. dissenting).

12

Atkins v. Virginia, 536 U.S. 304, 320 n.25 (2002).

36 37

minimum.”

13

Federal district judge Jed Rako struck down the federal

death penalty, arguing: “We now know, in a way almost unthinkable

even a decade ago, that our system of criminal justice, for all its pro-

tections, is suciently fallible that innocent people are convicted of

capital crimes with some frequency.” His ruling was later reversed

by the Second Circuit Court of Appeals.

14

Statewide moratoriums

and abolition of the death penalty have occurred in part citing the

examples of death row exonerations; the best known was the Illinois

moratorium and Commission on Capital Punishment, for which

there was intensive study of the cases of 13 men exonerated from

the Illinois death row.

15

Hearing from a death row exoneree how a

wrongful execution nearly happened can have a powerful eect on

legislators and the public. As noted, the death penalty was abolished

in Maryland; death row survivor Kirk Bloodsworth had lobbied for

the repeal in Maryland and has done so across the country. The direc-

tor of Maryland Citizens Against State Executions commented, “No

single individual has changed as many minds as Kirk.”

16

Looking far beyond death penalty cases, DNA testing suggests addi-

tional questions about the more mundane criminal cases. A federal

inquiry conducted in the mid-1990s, when police rst began to send

samples for DNA testing, found that 25percent of these prime sus-

pects were cleared by DNA before a trial was held.

17

Where the vast

majority of criminal cases lack any DNA evidence to test, still more

questions are raised concerning accuracy.

13 Kansas v. Marsh, 548 U.S. 163, 194-195 (2006) (Scalia, J. concurring). For a discussion, see

Samuel R. Gross, “Souter passant, Scalia rampant: Combat in the marsh”, Michigan Law Review

First Impressions, vol. 105 (2006), pp. 67 .

14

U.S. v. Quinones, 196 F.Supp.2d 416, 420 (S.D.N.Y. 2002) rev’d U.S. v. Quinones, 313 F.3d 49

(2nd Cir. 2002).

15 Governor’s Commission on Capital Punishment,

Report of the Governor’s Commission on Capi-

tal Punishment (Springeld, Illinois, 2002), p. 4.

16 Scott Shane, “A death penalty ght comes home”,

New York Times, 5 February 2013.

17 Edward Connors and others,

Convicted by Juries, Exonerated by Science: Case Studies in the Use

of DNA Evidence to Establish Innocence after Trial (Washington, DC, US Department of Justice,

1996), pp. xxviii-xxix, 20.

“OVER 140 DEATH ROW INMATES HAVE

BEEN EXONERATED SINCE THE 1970S IN

THE UNITED STATES” —

Brandon L. Garrett

More states and local police departments are now recording interro-

gations and have adopted best practices for eyewitness lineups. A few

have also improved quality control and standards for forensics. Those

reforms are inexpensive, and they benet law enforcement; they help

to identify the guilty and clear the innocent. However, they are all

being implemented at the local and state levels.

Additional reforms could improve the quality of post-convic-

tion review. One state, North Carolina, has created an Innocence

Inquiry Commission, to focus on judicial review of claims of inno-

cence. Unlike post-conviction and habeas courts, which are sharply

restricted by complex procedural barriers to relief, this Commission

just investigates whether a person is innocent and should be exoner-

ated by a three-judge panel. Other courts have made improvements

on the front end by insisting that juries be carefully informed of the

limitations of evidence, such as eyewitness testimony. Much more can

be done, however, both to improve judicial gatekeeping to prevent

wrongful convictions in the rst place and to review convictions after

the fact.

CONCLUSION

In the United States, because some jurisdictions happened to save

crime scene evidence that could be tested years later, there has been

No challenge Verdict reversed Challenge unsuccessful

Eyewitness testimony

56% challenged

Forensic testimony

31% challenged

Informant testimony

34% challenged

Confessions

59% challenged

120

100

80

60

40

20

0

38 39

a remarkable series of DNA exonerations, including in death penalty

cases. Jurisdictions in the United States are slowly learning from these

cases, and some have adopted reforms to prevent future wrongful