Calendar No. 758

79TH

CONGRESS

SENATE

REPORT

1st

Session

No.

752

ADMINISTRATIVE PROCEDURE

ACT

REPORT

OF

THE

COMMITTEE

ON

THE JUDICIARY

ON

S.

7

A BILL TO IMPROVE THE ADMINISTRATION

OF JUSTICE BY PRESCRIBING FAIR

ADMINISTRATIVE PROCEDURE

NOVEMBER

19 (legislative day,

OCTOBER

29), 1945.—Ordered to be printed

185

COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY

PAT McCARRAN, Nevada, Chairman

CARL A. HATCH, New Mexico

JOSEPH C. O'MAHONEY, Wyoming

HARLEY M. KILGORE, West Virginia

ABE MURDOCK, Utah

ERNEST W, McFARLAND, Arizona

BURTON K. WHEELER, Montana

CHARLES O. ANDREWS, Florida

JAMES O. EASTLAND, Mississippi

JAMES W. HUFFMAN, Ohio

(vacancy)

ALEXANDER WILEY, Wisconsin

WILLIAM LANGER, North Dakota

HOMER FERGUSON, Michigan

CHAPMAN REVERCOMB, West Virginia

KENNETH S. WHERRY, Nebraska

E. H. MOORE, Oklahoma

H. ALEXANDER SMITH, New Jersey

CALVIN M. CORY,

Clerk

J. G.

SOURWINE,

Counsel

186

Calendar

No.

75 8

79TH CONGRESS SENATE

REPORT

1st Session No. 752

ADMINISTRATIVE PROCEDURE ACT

NOVEMBER

19 (legislative day,

OCTOBER

29), 1945.—Ordered to be printed

Mr. MCCARRAN, from the Committee on the Judiciary,

submitted the following

REPORT

[To accompany S. 7]

The Committee on the Judiciary, to whom was referred the bill

(S.

7), to improve the administration of justice by prescribing fair

administrative procedure, having considered the same, reports favor-

ably thereon, with an amendment, and recommend that the bill do

pass,

as amended.

There is a widespread demand for legislation to settle and regulate

the field of Federal administrative law and procedure. The subject is

not expressly mentioned in the Constitution, and there is no recogniz-

able body of such law, as there is for the courts in the Judicial Code.

There are no clearly recognized legal guides for either the public or

the administrators. Even the ordinary operations of administrative

agencies are often difficult to know. The Committee on the Judiciary

is convinced that, at least in essentials, there should be some simple

and standard plan of administrative procedure.

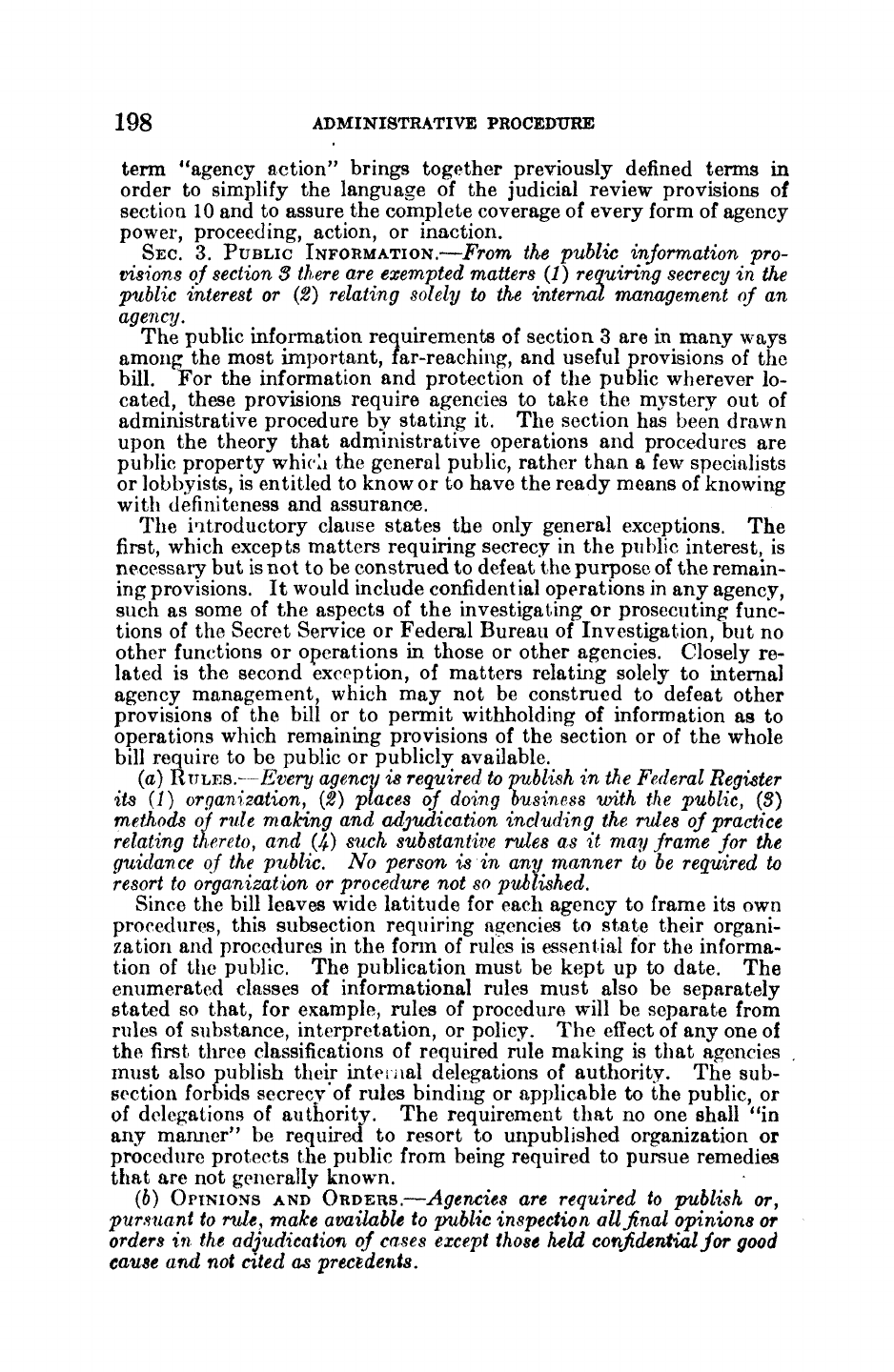

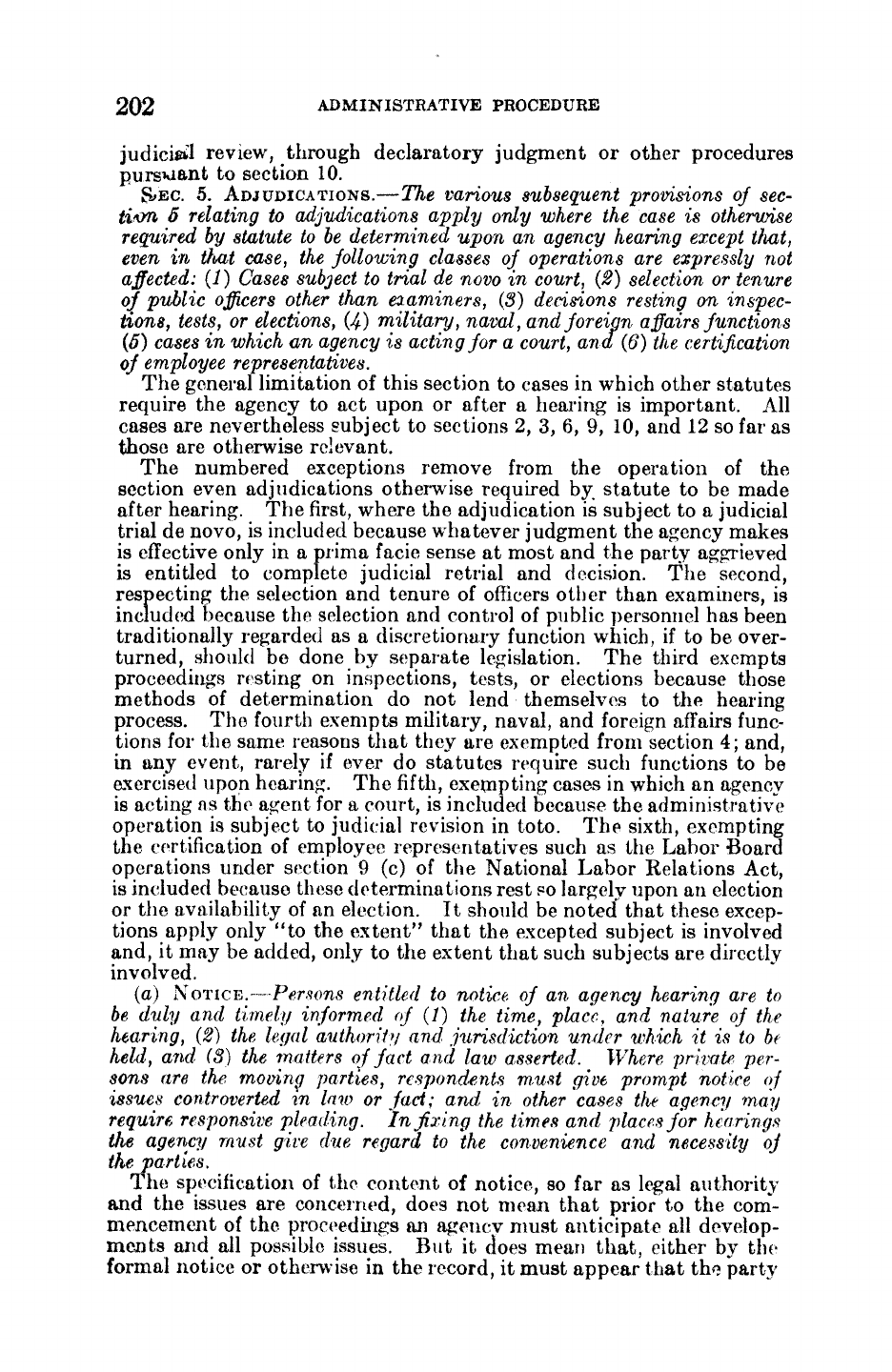

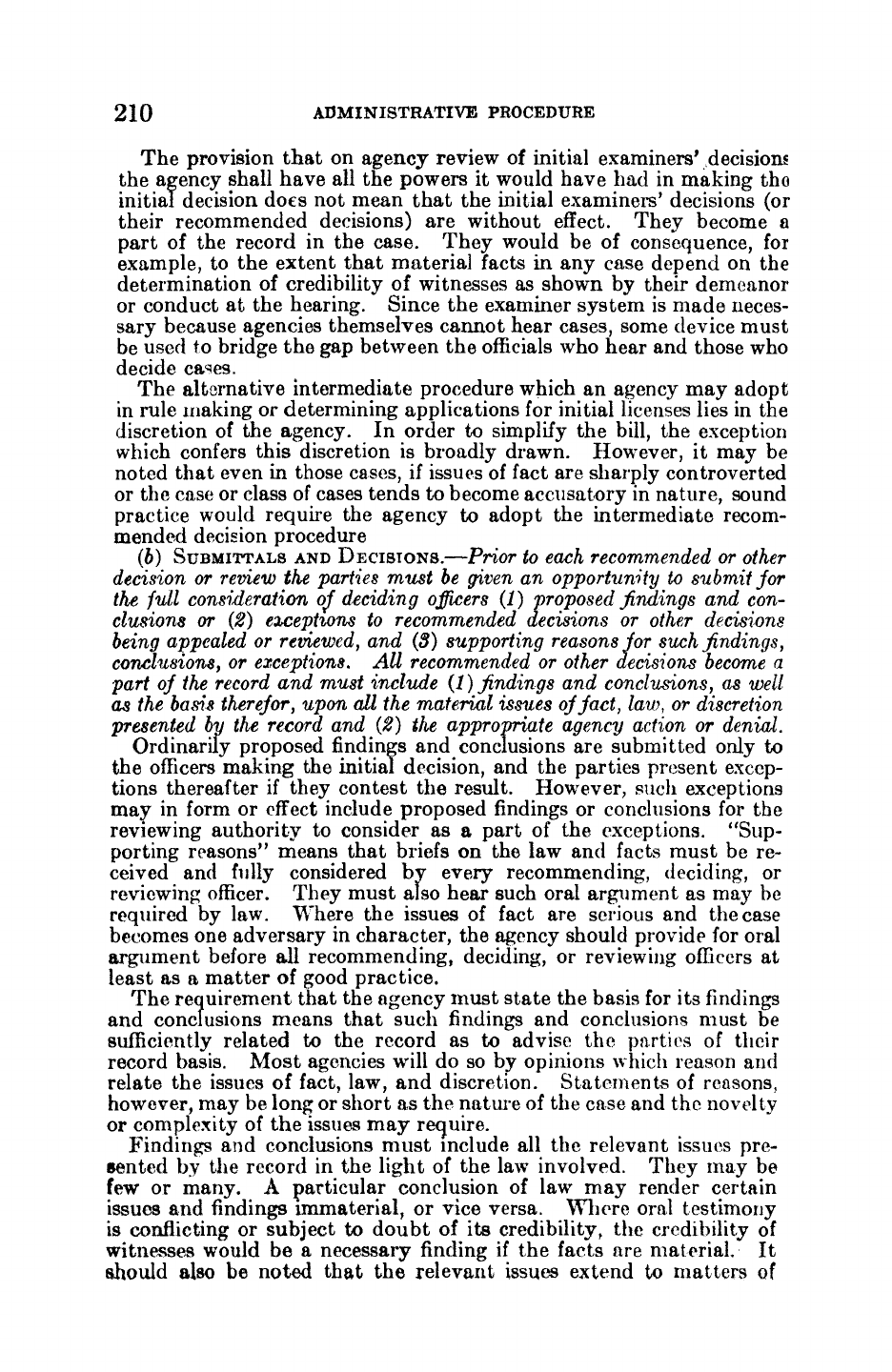

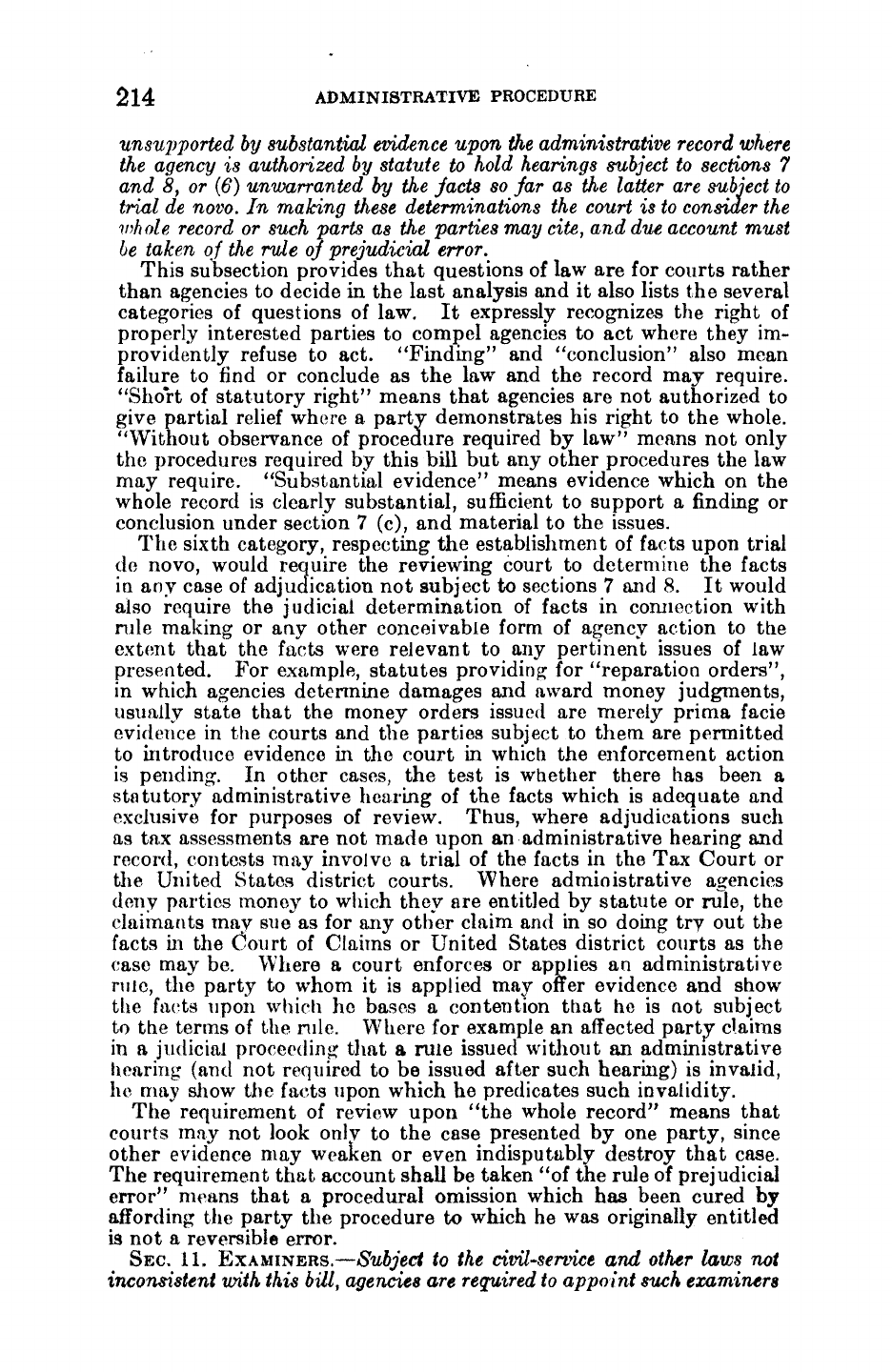

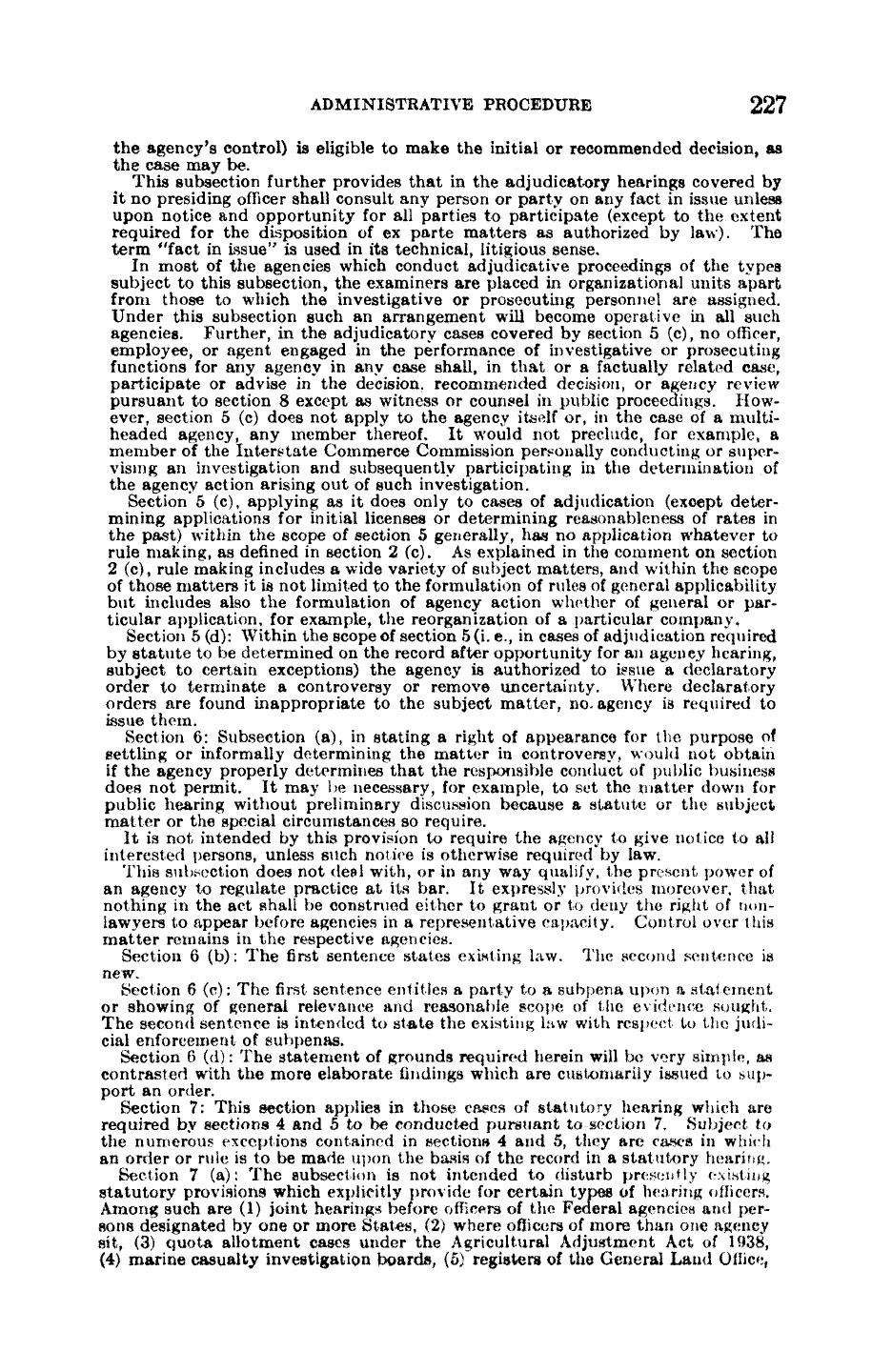

I. LEGISLATIVE HISTORY

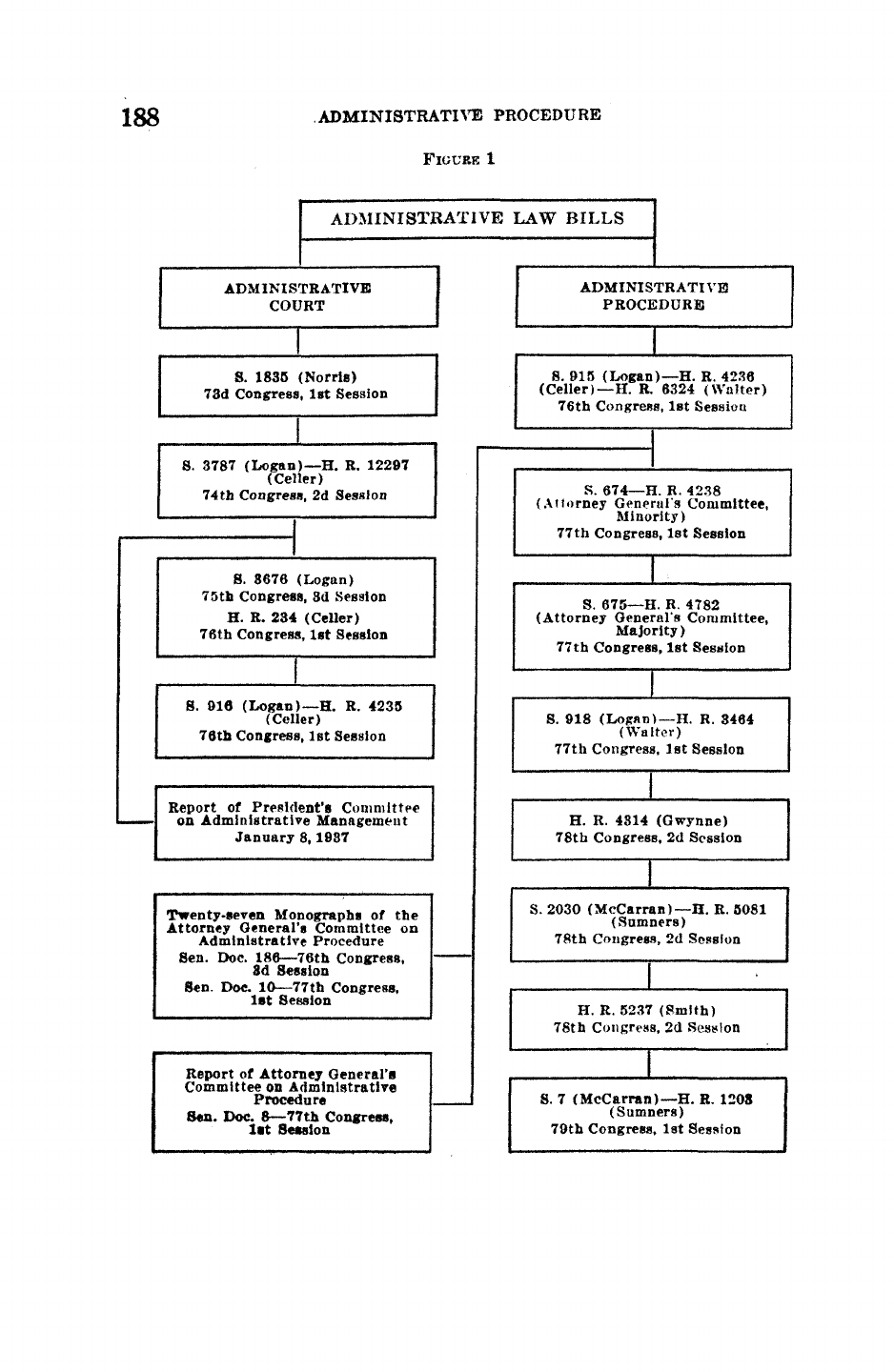

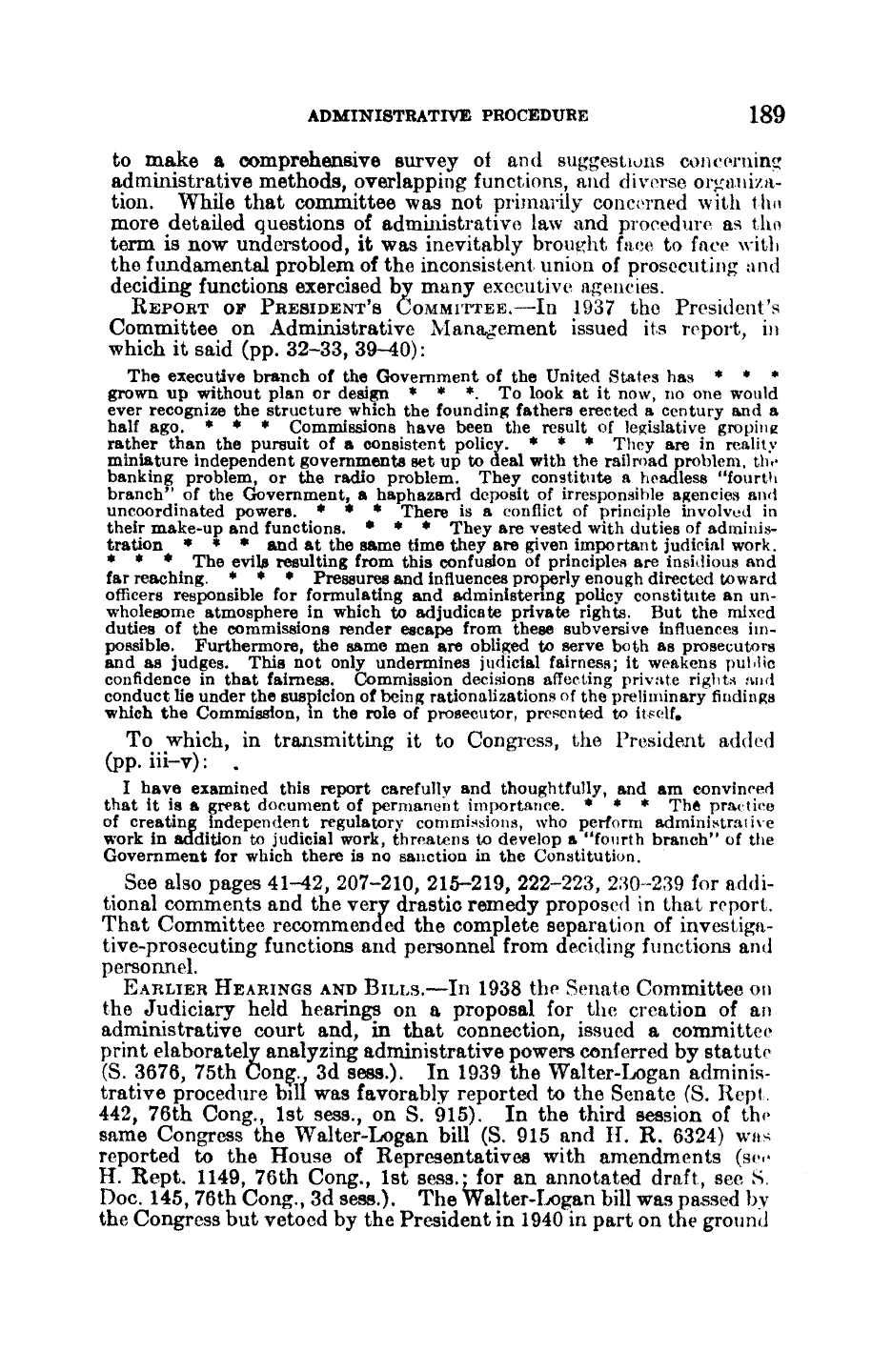

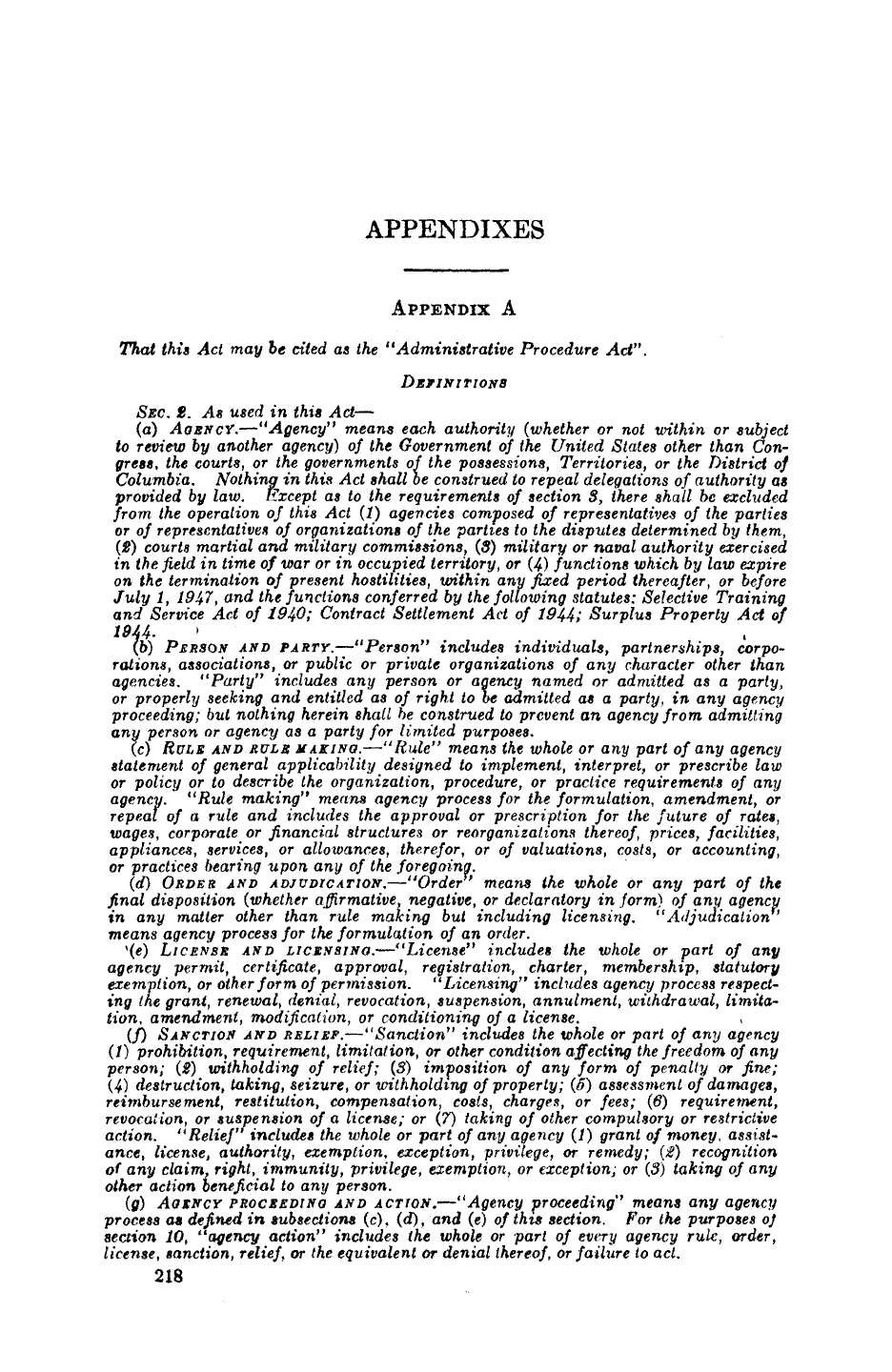

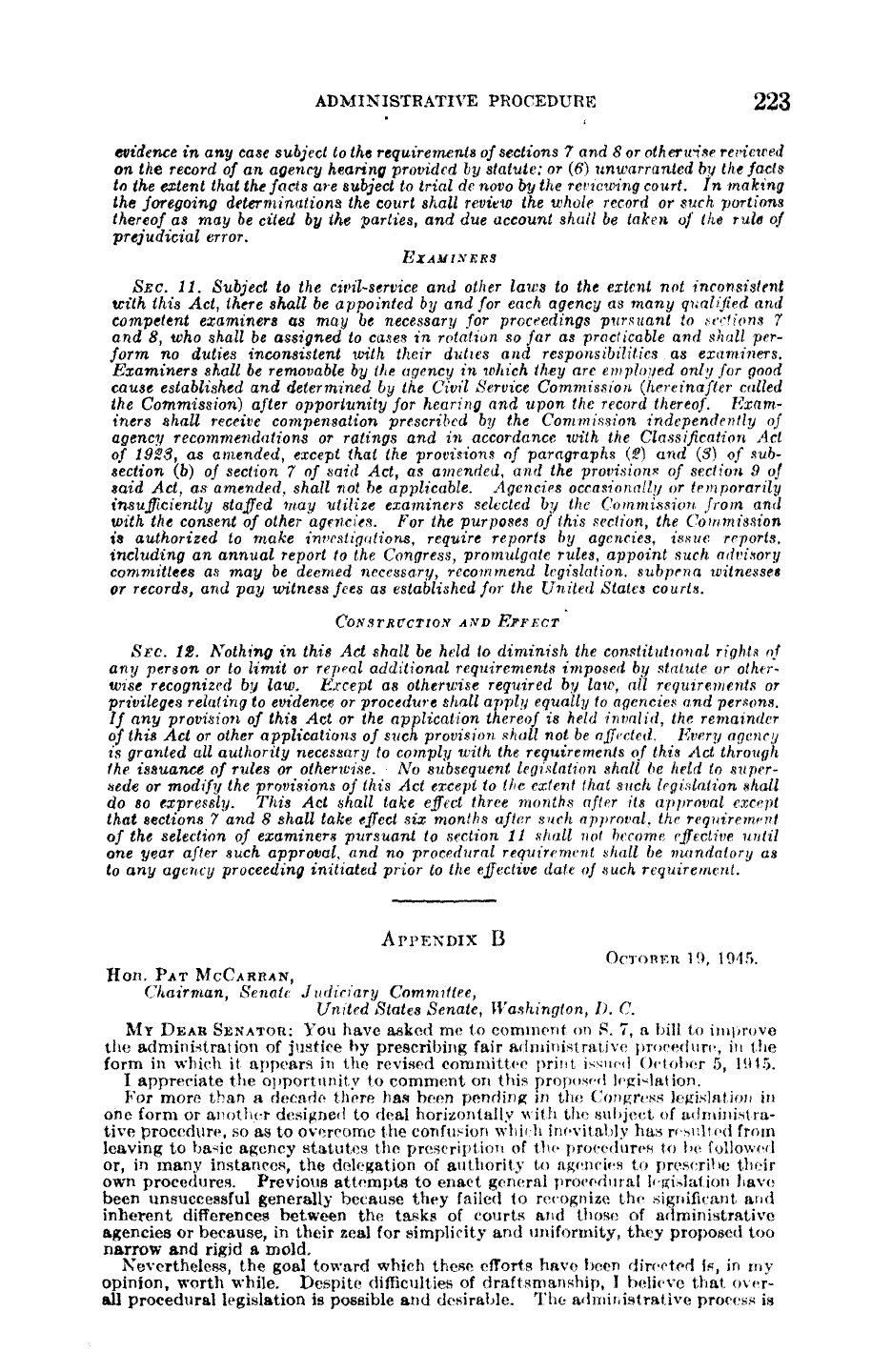

For more than 10 years Congress has considered proposals for

general statutes respecting administrative law and procedure. Figure

1 on page 2 presents a convenient chronological chart of the main

bills introduced. Each of them has received widespread notice and

intense consideration.

The growth of the Government, particularly of the executive

branch, has added to the problem. The situation had become such

by the middle of the 1930's that the President appointed a committee

90600—46 13 187

188

ADMINISTRATIVE PROCEDURE

FIGURE

1

ADMINISTRATIVE

ADMINISTRATIVE

COURT

S. 1835

(Norris)

73d Congress,

1st

Session

S.

3787 (Logan)—H.

R.

12297

(Celler)

74th Congress,

2d

Session

S.

3676 (Logan)

75th Congress,

3d

Session

H.

R. 234

(Celler)

76th Congress,

1st

Session

S. 916

(Logan)—H.

R.

4235

(Celler)

76th Congress,

1st

Session

Report

of

President's Committee

on Administrative Management

January 8,1937

Twenty-seven Monographs

of the

Attorney General's Committee

on

Administrative Procedure

Sen.

Doc.

186—76th Congress,

3d Session

Sen.

Doc.

10—77th Congress,

1st Session

Report

of

Attorney General's

Committee

on

Administrative

Procedure

Sen.

Doc.

8—77th

Congress,

1st

Session

LAW BILLS

ADMINISTRATIVE

PROCEDURE

S.

915

(Logan)—H.

R.

4238

(Celler)—H.

R.

6324 (Walter)

76th Congress,

1st

Session

S. 674—H.

R.

4238

(Attorney General's Committee,

Minority)

77th Congress,

1st

Session

S. 675—H.

R.

4782

(Attorney General's Committee,

Majority)

77th Congress,

1st

Session

S.

918

(Logan)—H.

R.

3464

(Walter)

77th Congress,

1st

Session

H.

R. 4814

(Gwynne)

78th Congress,

2d

Session

S.

2030 (McCarran)—H.

R. 5081

(Sumners)

78th Congress,

2d

Session

H.

R.

5237 (Smith)

78th Congress,

2d

Session

S.

7

(McCarran)—H.

R. 1208

(Sumners)

79th Congress,

1st

Session

ADMINISTRATIVE PROCEDURE 189

to

make a comprehensive survey of and suggestions concerning

administrative

methods, overlapping functions, and diverse organiza-

tion.

While that committee was not primarily concerned with the

more

detailed questions of administrative law and procedure as the

term

is now understood, it was inevitably brought face to face with

the

fundamental problem of the inconsistent union of prosecuting and

deciding

functions exercised by many executive agencies.

REPORT

OF PRESIDENT'S COMMITTEE.—In 1937 the President's

Committee

on Administrative Management issued its report, in

which

it said (pp.

32-33,

39-40):

The executive branch of the Government of the United States has * * *

grown up without plan or design * * *. To look at it now, no one would

ever recognize the structure which the founding fathers erected a century and a

half ago. * * * Commissions have been the result of legislative groping

rather than the pursuit of a consistent policy. * * * They are in reality

miniature independent governments set up to deal with the railroad problem, the

banking problem, or the radio problem. They constitute a headless "fourth

branch" of the Government, a haphazard deposit of irresponsible agencies and

uncoordinated powers. * * * There is a conflict of principle involved in

their make-up and functions. * * * They are vested with duties of adminis-

tration * * * and at the same time they are given important judicial work.

*

* * The evils resulting from this confusion of principles are insidious and

far reaching. * * * Pressures and influences properly enough directed toward

officers responsible for formulating and administering policy constitute an un-

wholesome atmosphere in which to adjudicate private rights. But the mixed

duties of the commissions render escape from these subversive influences im-

possible. Furthermore, the same men are obliged to serve both as prosecutors

and as judges. This not only undermines judicial fairness; it weakens public

confidence in that fairness. Commission decisions affecting private rights and

conduct lie under the suspicion of being rationalizations of the preliminary findings

which the Commission, in the role of prosecutor, presented to

itself.

To

which, in transmitting it to Congress, the President added

(pp.

iii-v):

I have examined this report carefully and thoughtfully, and am convinced

that it is a great document of permanent importance. * * * The practice

of creating independent regulatory commissions, who perform administrative

work in addition to judicial work, threatens to develop a "fourth branch" of the

Government for which there is no sanction in the Constitution.

See

also pages 41-42, 207-210, 215-219, 222-223, 230-239 for addi-

tional

comments and the very drastic remedy proposed in that report.

That

Committee recommended the complete separation of investiga-

tive-prosecuting

functions and personnel from deciding functions and

personnel.

EARLIER

HEARINGS

AND

BILLS.—In

1938 the Senate Committee on

the

Judiciary held hearings on a proposal for the creation of an

administrative

court and, in that connection, issued a committee

print

elaborately analyzing

administrative powers

conferred by statute

(S.

3676, 75th Cong., 3d sess.). In 1939 the Walter-Logan adminis-

trative

procedure bill was favorably reported to the Senate (S. Rept.

442,

76th Cong., 1st sess., on S. 915). In the third session of the

same

Congress the Walter-Logan bill (S. 915 and H. R. 6324) was

reported

to the House of Representatives with amendments (sec

H.

Rept. 1149, 76th Cong., 1st sess.; for an annotated draft, see S.

Doc.

145,

76th

Cong.,

3d

sess.).

The Walter-Logan bill was passed by

the Congress

but vetoed by the President in 1940 in part on the ground

19 0

ADMINISTRATIVE PROCEDURE

that action should await the then imminent final report by a commit-

tee appointed in the executive branch to study the entire situation

(H.

Doc. 986, 76th Cong., 3d sess.).

ATTORNEY

GENERAL'S COMMITTEE.—In December 1938 the

Attorney General, renewing the suggestion which he had previously

made respecting the need for procedural reform in the wide and grow-

ing field of administrative law, recommended the appointment of a

commission to make a thorough survey of existing practices and pro-

cedure and point the way to improvements (S. Doc. 8, 77th Cong.,

1st sess., p. 251). The President concurred and authorized the

Attorney General to appoint a committee for that purpose (id., p.

252).

This Committee was composed of Government officials,

teachers, judges, and private practitioners. It made an interim

report in January 1940 (id., 254-258). Its staff prepared, and in

1940-41 issued, a series of studies of the procedures of the principal

administrative agencies and bureaus in the Federal Government (S.

Doc.

186, 76th Cong., 3d sess., pts. 1-13; and S. Doc. 10, 77th Cong.,

1st sess., pts.

1-14).

The Committee held executive sessions over a

long period, at which the representatives of Federal agencies were

heard. It also held public hearings. It then prepared and issued

a voluminous final report. See Administrative Procedure in Govern-

ment Agencies—Report of the Committee on Administrative Procedure,

Appointed by the Attorney General, at the Request of the President, to

Investigate the Need for Procedural Reform in Various Administrative

Tribunals and to Suggest Improvements Therein (S. Doc. 8, 77th Cong.,

1st sess.). That Committee is popularly known as the Attorney

General's Committee on Administrative Procedure and will be so

designated in this report. In the framing of the bill herewith re-

ported, (S. 7), your committee has had the benefit of the factual

studies and analyses prepared by the Attorney General's Committee.

SUBSEQUENT

BILLS AND

HEARINGS.—Growing

out of the work of

the Attorney General's Committee on Administrative Procedure,

several bills were introduced in 1941 (S. 674, 675, and 918, 77th

Cong., 1st sess.). Hearings were held on these bills during April,

May, June, and July of that year. (See Administrative Procedure,

hearings, 77th Cong., 1st sess., pts. 1-3, plus appendix.) However,

the then emergent international situation prompted a postponement

of further consideration of the matter. But all interested adminis-

trative agencies were heard at length at that time and the proposals

then pending involved the same basic issues as the present bill.

PRESENT

BILL.—Based

upon the studies and hearings in connection

with prior bills on the subject, and after several years of consultation

with interested parties in and out of official positions, S. 2030 (78th

Cong., 2d sess.) was introduced on June 21, 1944, the companion bill

in the House of Representatives being H. R. 5081. The introduction

of these bills brought forth a volume of further suggestions from every

quarter. As a result, with the opening of the present Congress,

a revised and simplified bill was introduced (S. 7, January 6, 1945;

H. R. 1203, January 8, 1945).

CONSIDERATION

AND

REVISION.—Much

informal discussion followed

the introduction of S. 7 and H. R. 1203. The House of Representa-

tives'

Committee on the Judiciary held hearings in the latter part of

June 1945.

ADMINISTRATIVE PROCEDURE 191

Previously, that committee and the Senate Committee on the

Judiciary had requested administrative agencies to submit their

views in writing. These were carefully analyzed and, with the aid

of representatives of the Attorney General and interested private

organizations, in May 1945 there was issued a Senate committee print

setting forth in parallel columns the bill as introduced and a tentatively

revised text.

Again interested parties in and out of Government submitted com-

ments orally or in writing on the revised text. These were analyzed

by the committee's staff and a further committee print was issued in

June 1945. In four parallel columns it set forth (1) the text of the

bill as introduced, (2) the text of the tentatively revised bill previously

published, (3) a general explanation of provisions with references to

the report of the Attorney General's Committee on Administrative

Procedure and other authorities, and (4) a summary of views and sug-

gestions received.

Thereafter the Attorney General again designated representatives to

hold further discussions with interested agencies and to screen and

correlate further agency views, some of which were submitted in writ-

ing and some orally. Private parties and representatives of private

organizations also participated.

Following these discussions the committee drafted the bill as re-

ported, which is set forth in full in appendix A. The Attorney Gen-

eral's favorable report on the bill, as revised, is set forth in appendix B.

II.

APPROACH OF THE COMMITTEE

In undertaking the foregoing very lengthy process of consideration,

the committee has attempted to make sure that no operation of the

Government is unduly restricted. The committee has also taken the

position that the bill must reasonably protect private parties even at

the risk of some incidental or possible inconvenience to or change in

present administrative operations. The committee is convinced, how-

ever, that no administrative function is improperly affected by the

present bill.

TH E

PRINCIPAL

PROBLEMS.—The principal problems of the com-

mittee have been: First, to distinguish between different types of ad-

ministrative operations.

Second,

to frame general requirements appli-

cable to each such type of operation.

Third,

to set forth those require-

ments in clear and simple terms. Fourth, to make sure that the bill

is complete enough to cover the whole field.

The committee feels that it has avoided the mistake of attempting

to oversimplify the measure. It has therefore not hesitated to state

functional classifications and exceptions where those could be rested

upon firm grounds. In so doing, it has been the undeviating policy

to deal with types of functions as such and in no case with adminis-

trative agencies by name. Thus certain war and defense functions are

exempted, but not the War or Navy Departments in the performance

of their other functions. Manifestly, it would be folly to assume to

distinguish between "good" agencies and others, and no such distinc-

tion is made in the bill. The legitimate needs of the Interstate Com-

merce Commission, for example, have been fully considered but it has

not been placed in a favored position by exemption from the bill.

192

ADMINISTRATIVE

PROCEDURE

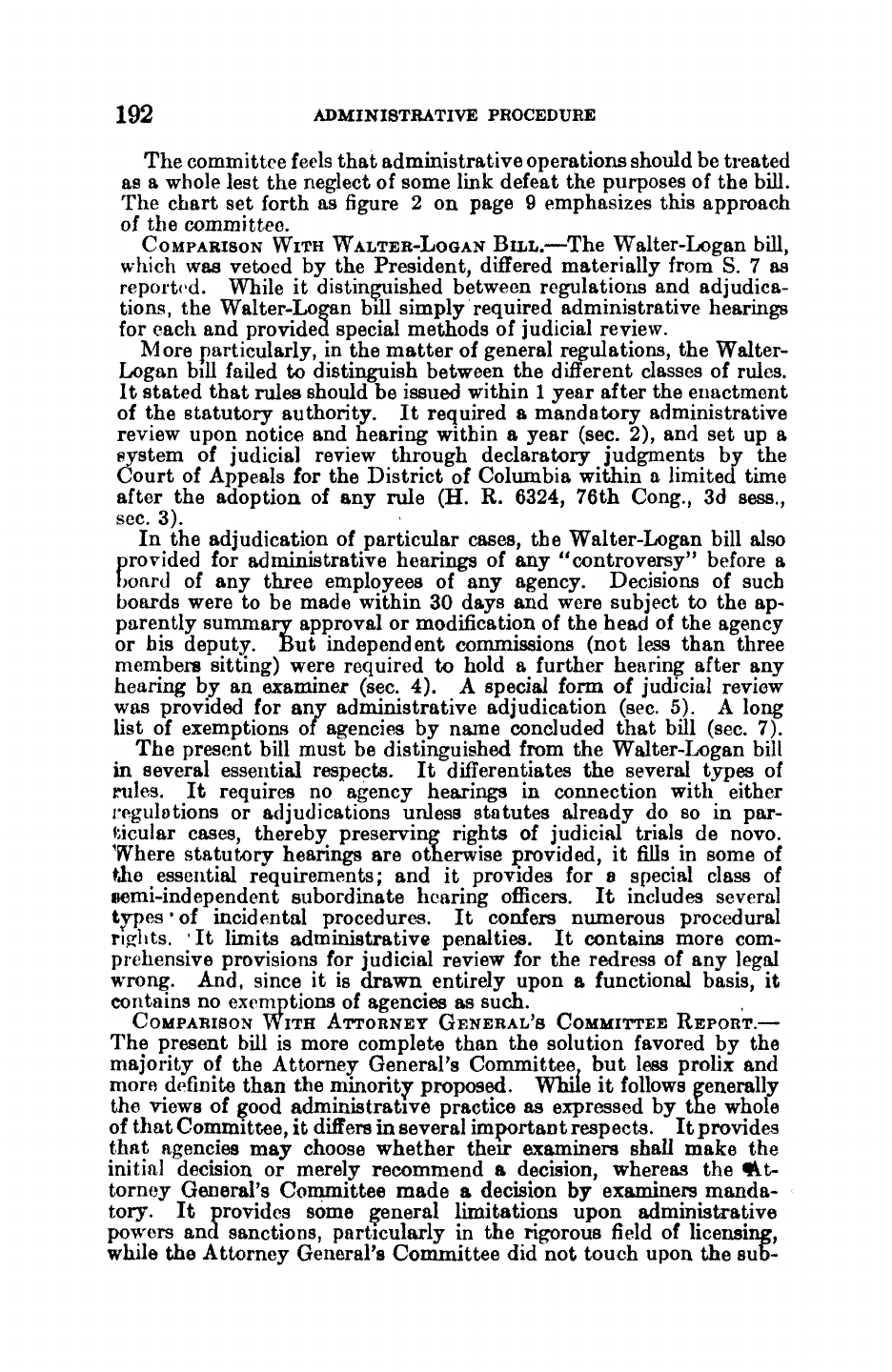

The committee feels that administrative operations should be treated

as a whole lest the neglect of some link defeat the purposes of the bill.

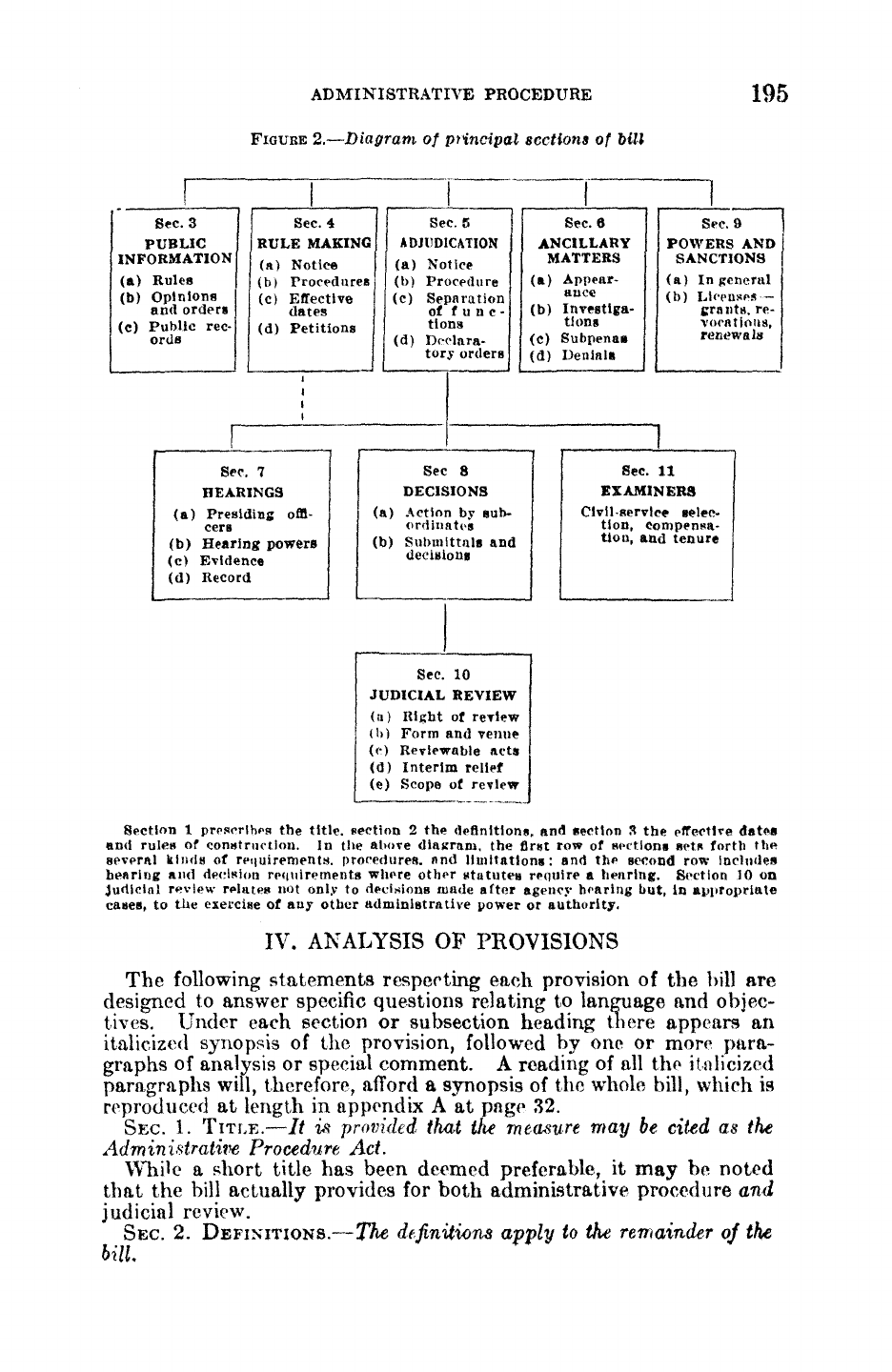

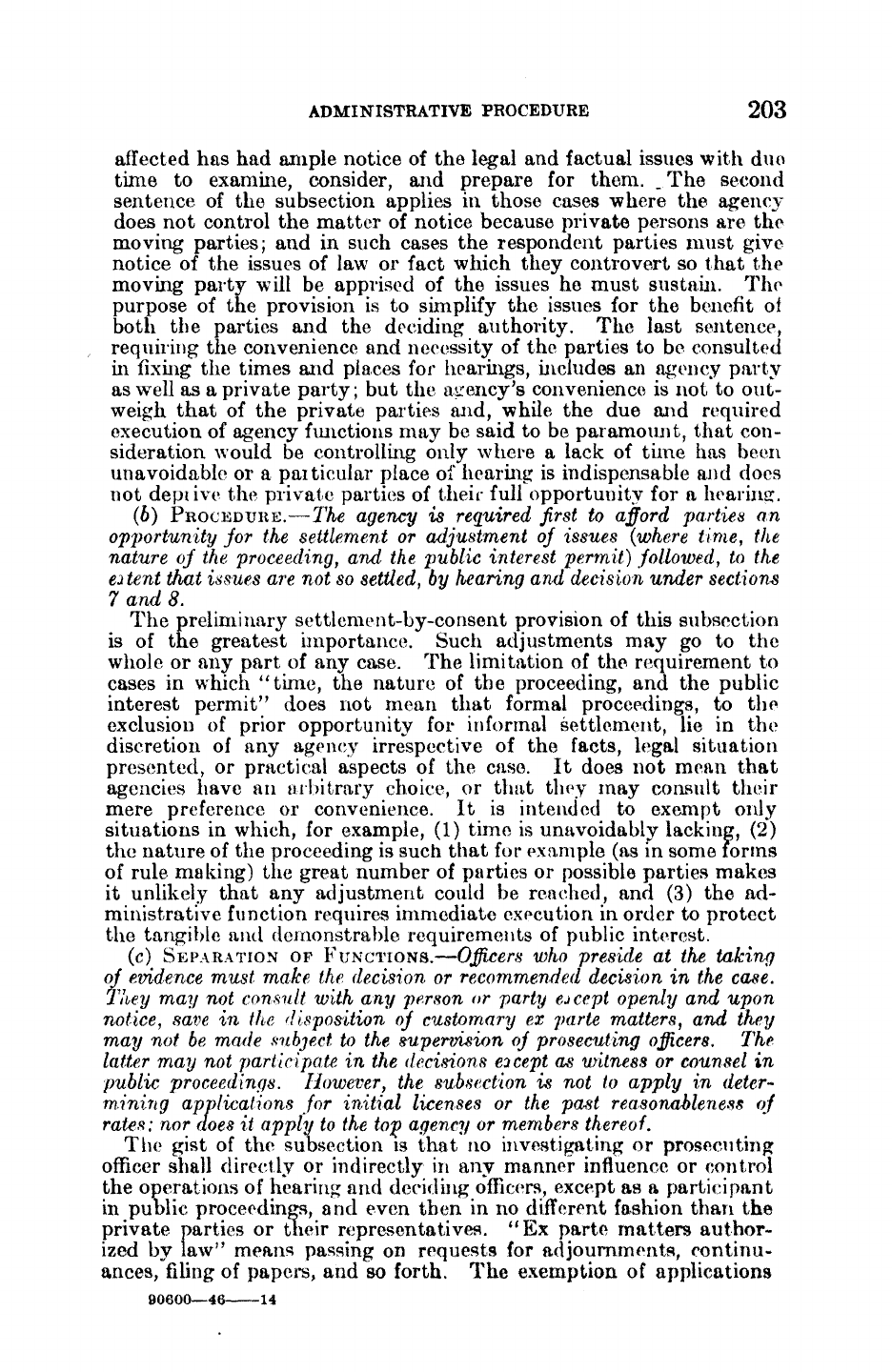

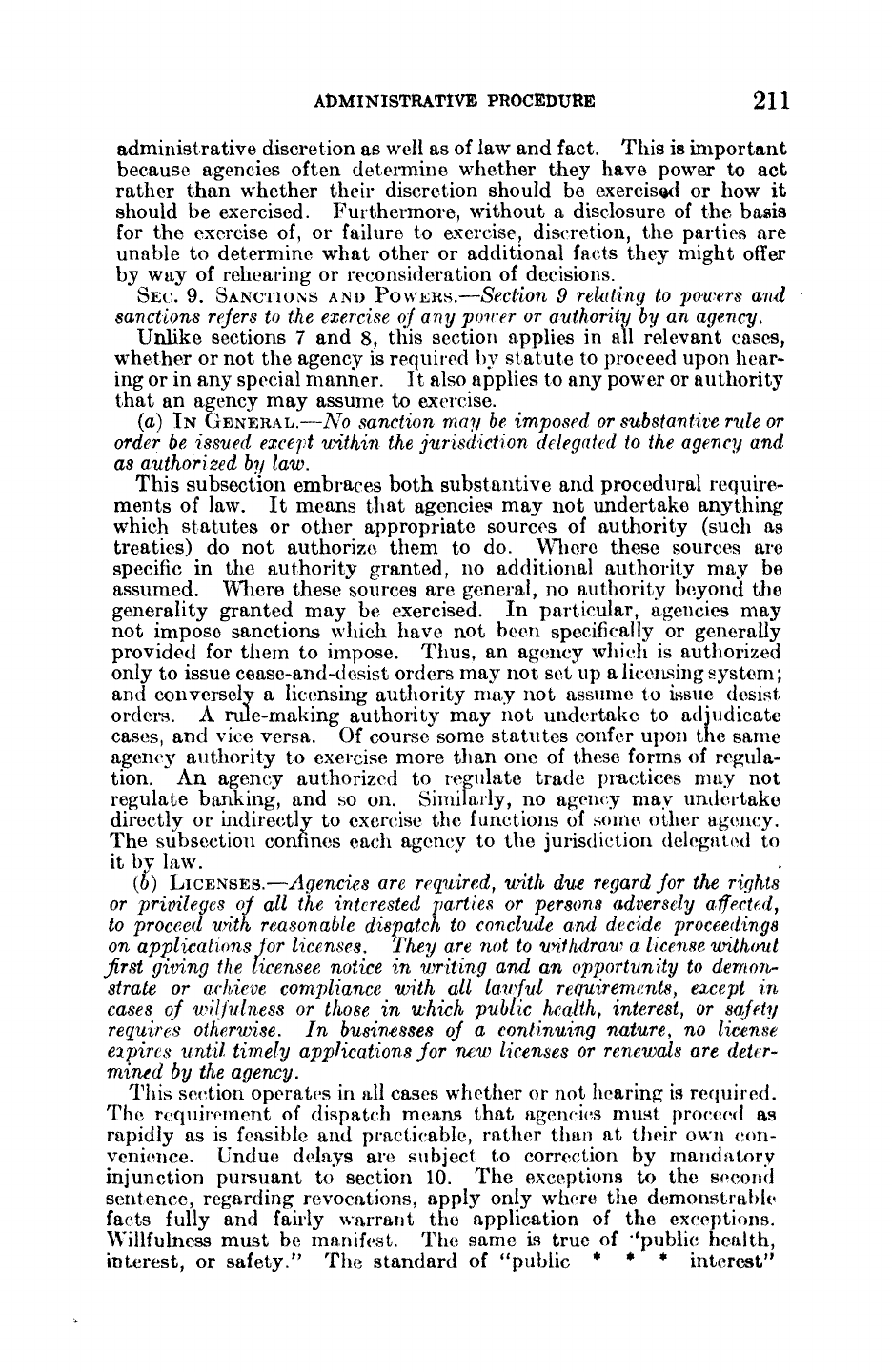

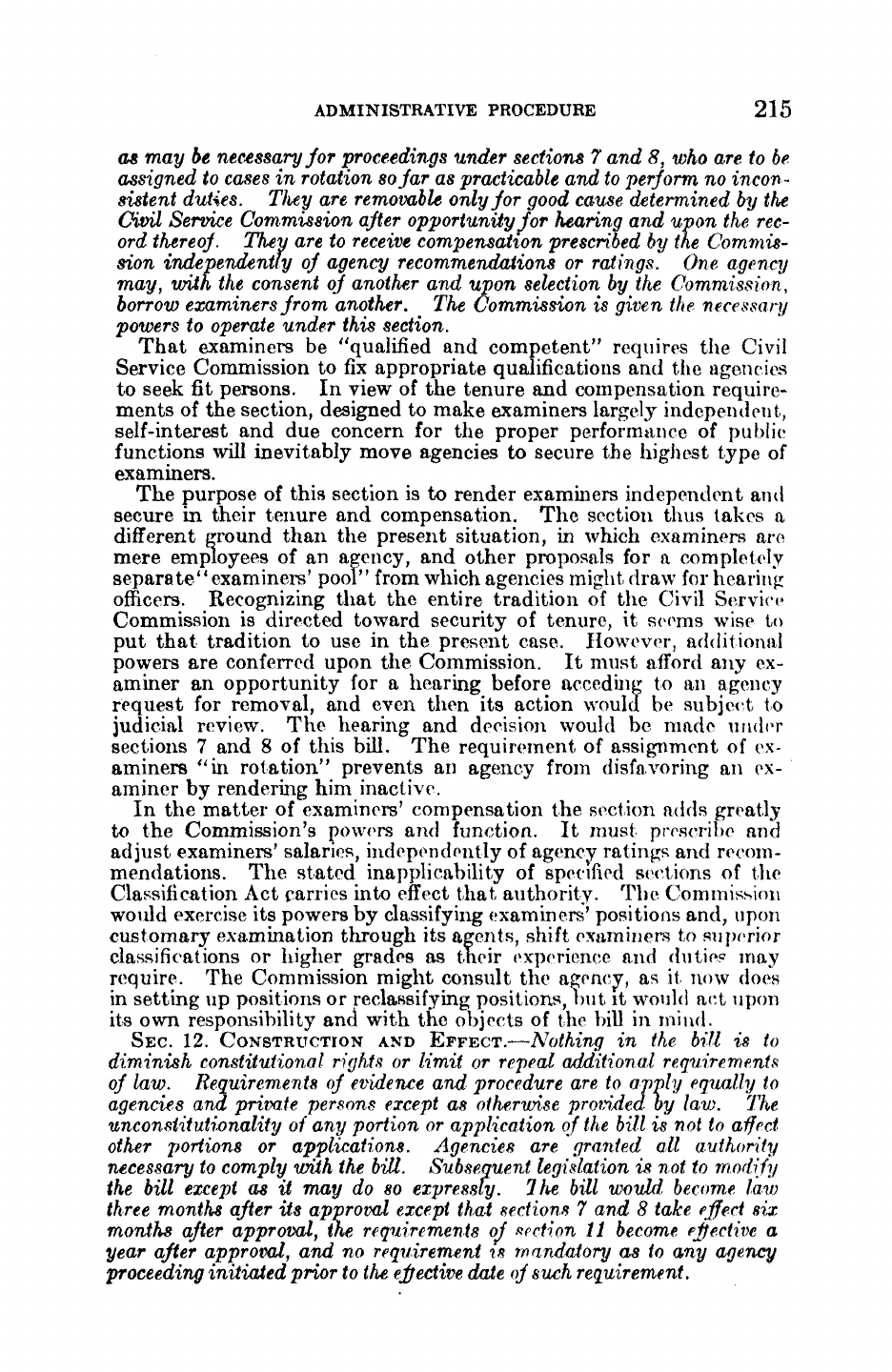

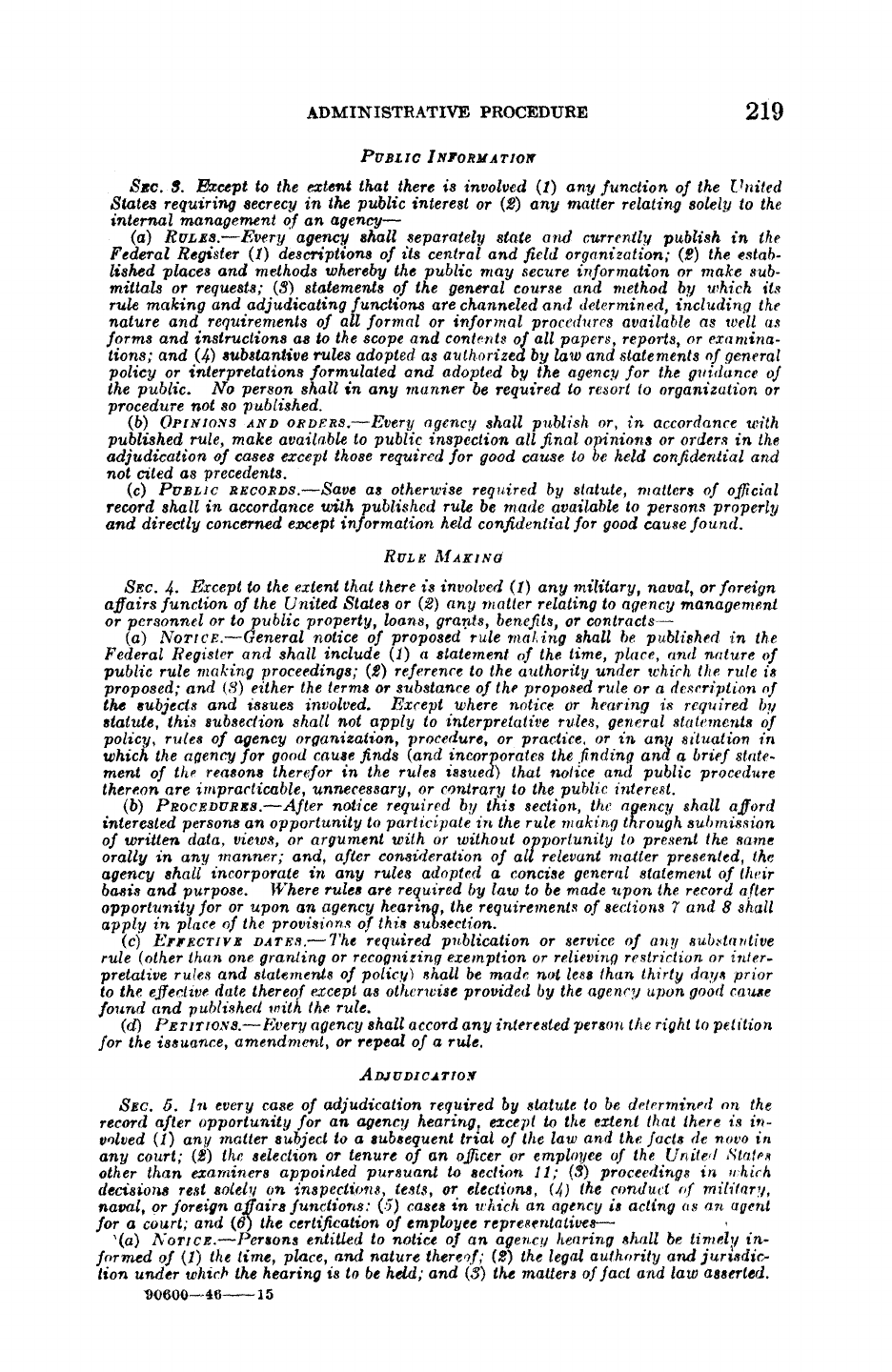

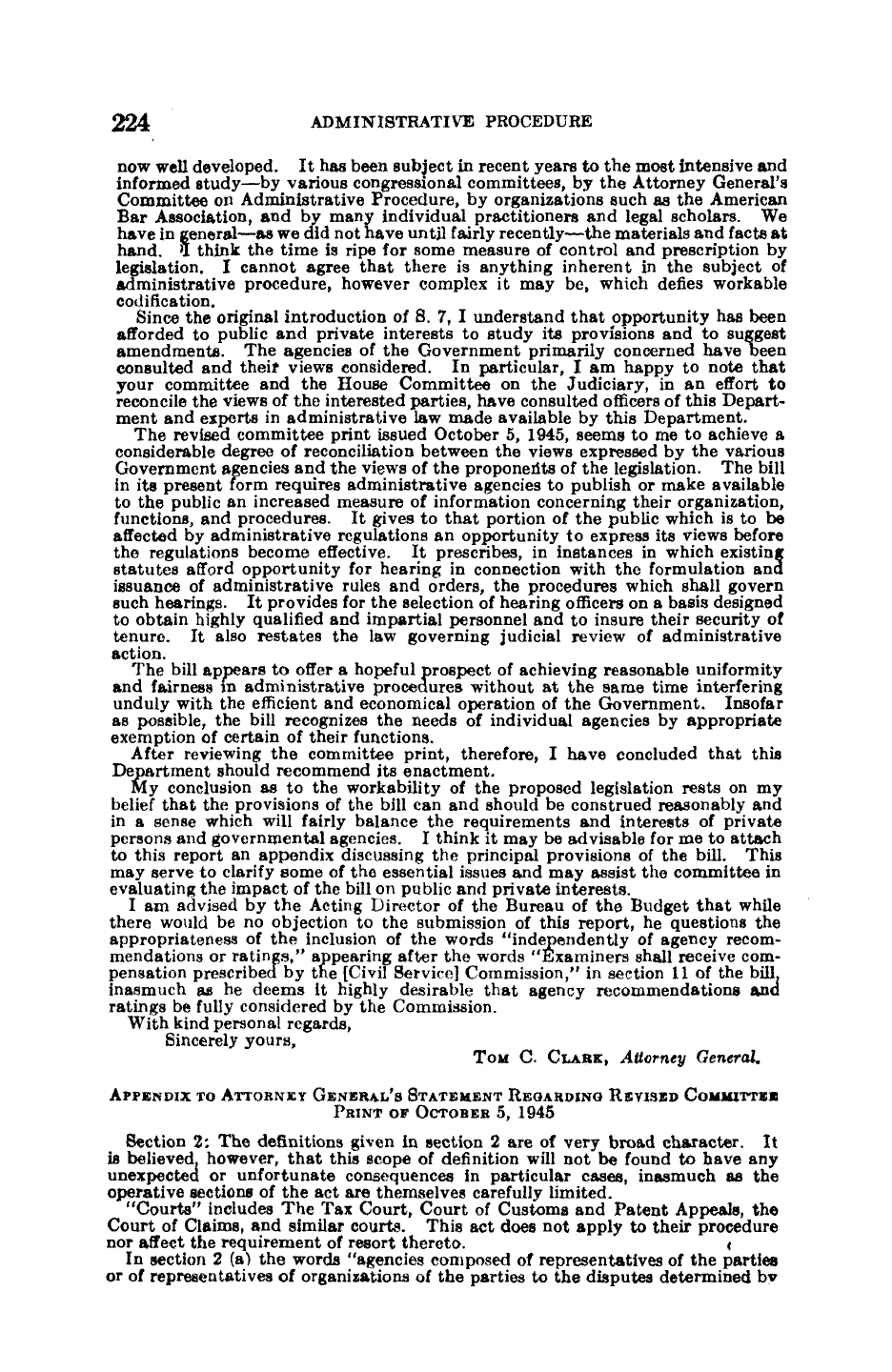

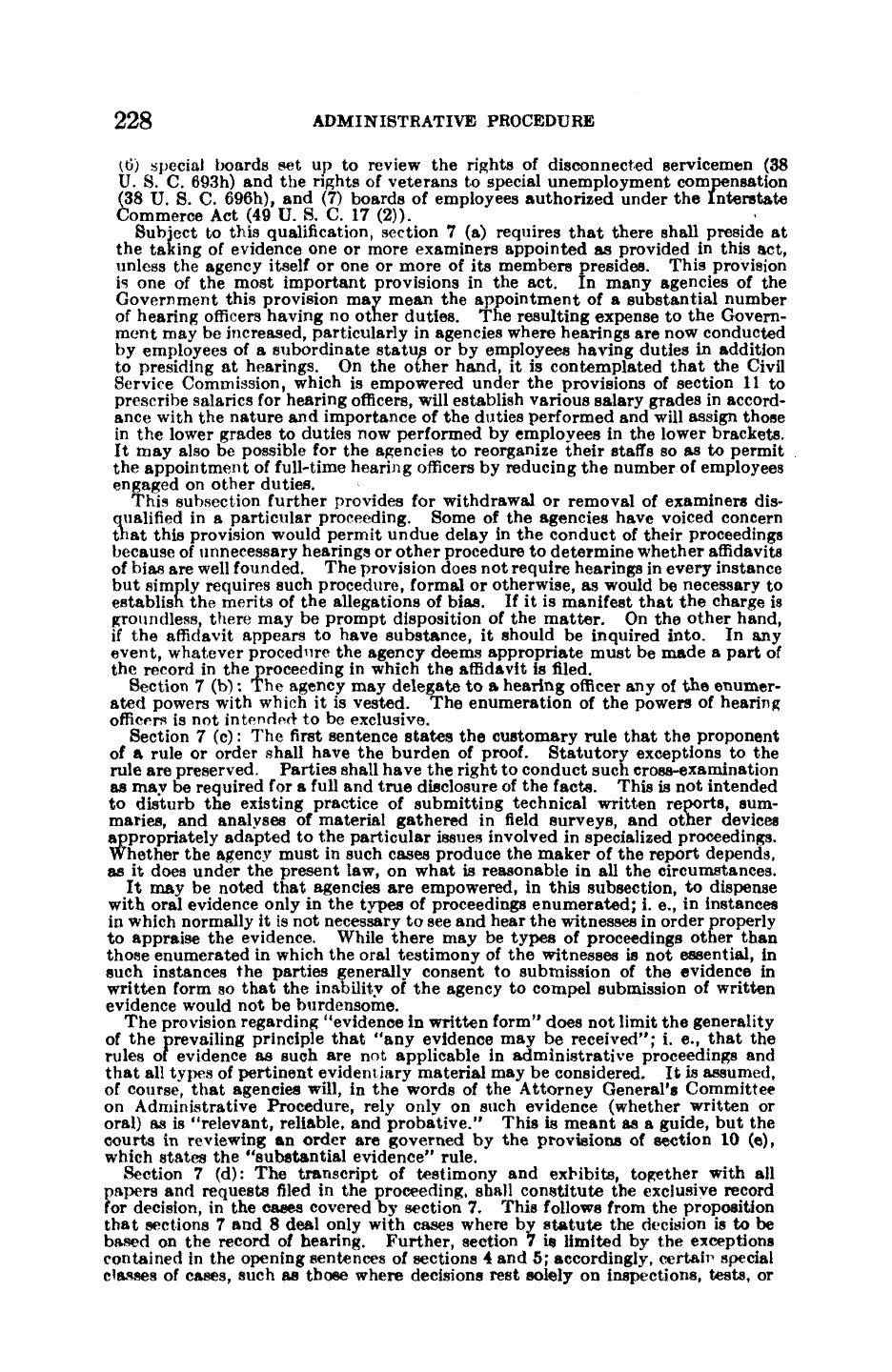

The chart set forth as figure 2 on page 9 emphasizes this approach

of the committee.

COMPARISON

WITH WALTER-LOGAN BILL.—The Walter-Logan bill,

which was vetoed by the President, differed materially from S. 7 as

reported. While it distinguished between regulations and adjudica-

tions,

the Walter-Logan bill simply required administrative hearings

for each and provided special methods of judicial review.

More particularly, in the matter of general regulations, the Walter-

Logan bill failed to distinguish between the different classes of rules.

It stated that rules should be issued within

1

year after the enactment

of the statutory authority. It required a mandatory administrative

review upon notice and hearing within a year (sec. 2), and set up a

system of judicial review through declaratory judgments by the

Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia within a limited time

after the adoption of any rule (H. R. 6324, 76th Cong., 3d sess.,

sec.

3).

In the adjudication of particular cases, the Walter-Logan bill also

provided for administrative hearings of any "controversy" before a

board of any three employees of any agency. Decisions of such

boards were to be made within 30 days and were subject to the ap-

parently summary approval or modification of the head of the agency

or his deputy. But independent commissions (not less than three

members sitting) were required to hold a further hearing after any

hearing by an examiner (sec. 4). A special form of judicial review

was provided for any administrative adjudication (sec. 5). A long

list of exemptions of agencies by name concluded that bill (sec. 7).

The present bill must be distinguished from the Walter-Logan bill

in several essential respects. It differentiates the several types of

rules. It requires no agency hearings in connection with either

regulations or adjudications unless statutes already do so in par-

ticular cases, thereby preserving rights of judicial trials de novo.

Where statutory hearings are otherwise provided, it fills in some of

the essential requirements; and it provides for a special class of

semi-independent subordinate hearing officers. It includes several

types of incidental procedures. It confers numerous procedural

rights.

It limits administrative penalties. It contains more com-

prehensive provisions for judicial review for the redress of any legal

wrong. And, since it is drawn entirely upon a functional basis, it

contains no exemptions of agencies as such.

COMPARISON

WITH ATTORNEY GENERAL'S COMMITTEE REPORT.—

The present bill is more complete than the solution favored by the

majority of the Attorney General's Committee, but less prolix and

more definite than the minority proposed. While it follows generally

the views of good administrative practice as expressed by the whole

of that Committee, it differs in several important

respects.

It provides

that agencies may choose whether their examiners shall make the

initial decision or merely recommend a decision, whereas the At-

torney General's Committee made a decision by examiners manda-

tory. It provides some general limitations upon administrative

powers and sanctions, particularly in the rigorous field of licensing,

while the Attorney General's Committee did not touch upon the sub-

ADMINISTRATIVE PROCEDURE

193

ject. It relies upon independence, salary security, and tenure during

good behavior of examiners within the framework of the civil service,

whereas the Attorney General's Committee favored short-term ap-

pointments approved by a special "Office of Administrative Pro-

cedure."

A more detailed comparison of the present bill, with full references

to the report of the Attorney General's Committee, is to be found in

the third parallel column of the print issued by this committee in

June 1945.

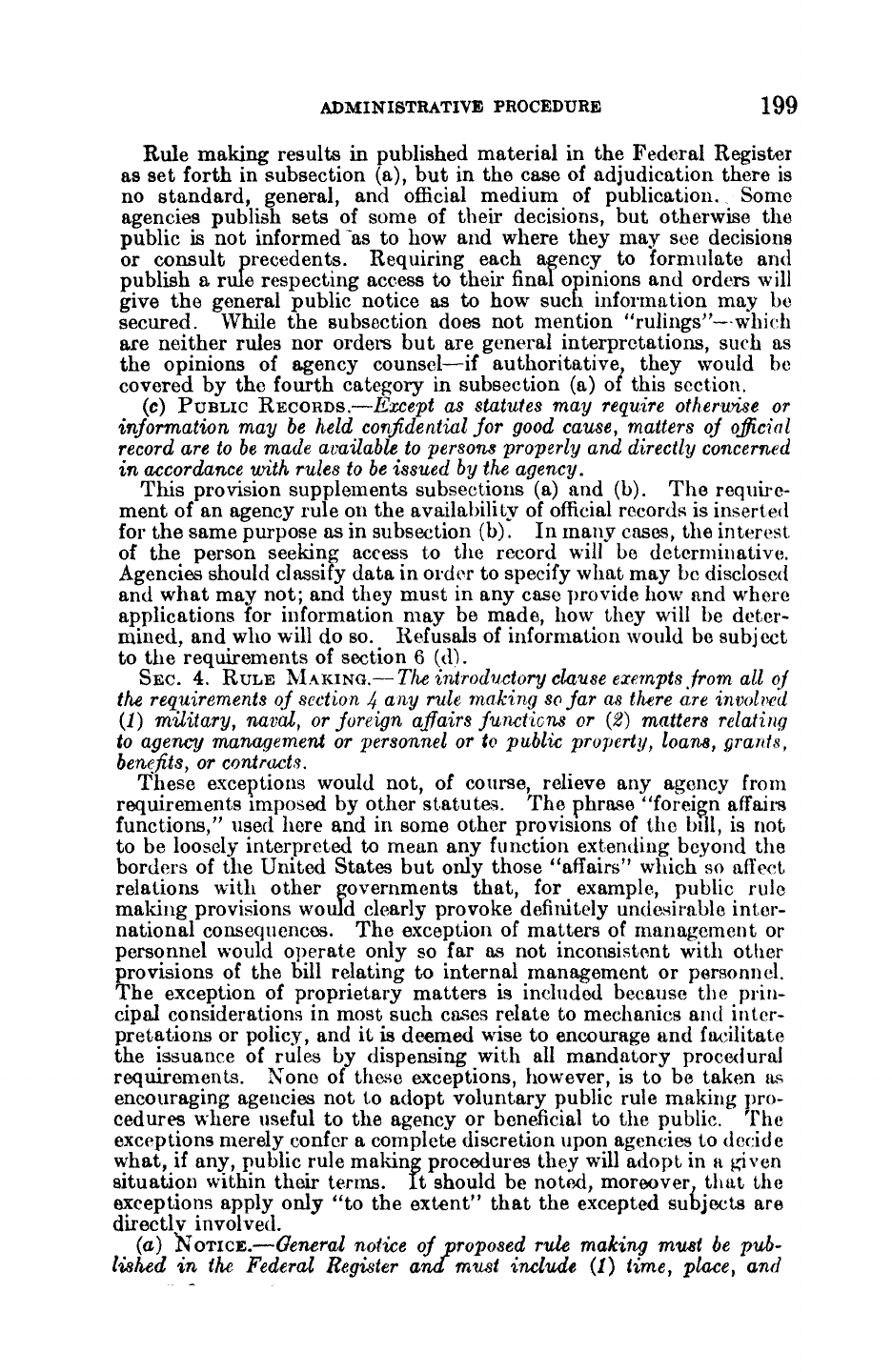

III.

STRUCTURE OF THE BILL

The bill, as reported, is not a specification of the details of admin-

istrative procedure, nor is it a codification of administrative law.

Instead, out of long consideration and in the light of the studies here-

tofore mentioned, there has been framed an outline of minimum basic

essentials. Figure 2 on page 9 diagrams the bill.

The bill is designed to afford parties affected by administrative

powers a means of knowing what their rights are and how they may be

protected. By the same token, administrators are provided with a

simple course to follow in making administrative determinations.

The jurisdiction of the courts is clearly stated. The bill thus pro-

vides for public information, administrative operation, and judicial

review.

SUBSTANCE

OF THE BILL.—What the bill does in substance may be

summarized under four headings:

1.

It provides that agencies must issue as rules certain specified

information as to their organization and procedure, and also

make available other materials of administrative law

(sec.

3).

2.

It states the essentials of the several forms of administrative

proceedings (secs. 4, 5, and 6) and the limitations on ad-

ministrative powers (sec. 9).

3.

It provides in more detail the requirements for administrative

hearings and decisions in cases in which statutes require

such hearings (secs. 7 and 8).

4.

It sets forth a simplified statement of judicial review designed

to afford a remedy for every legal wrong (sec. 10).

The first of these is basic, because it requires agencies to take the

initiative in informing the public. In stating the essentials of the

different forms of administrative proceedings, it carefully distinguishes

between the so-called legislative functions of administrative agencies

(where they issue general regulations) and their judicial functions

(in which they determine rights or liabilities in particular cases).

The bill provides quite different procedures for the "legislative"

and "judicial" functions of administrative agencies. In the "rule

making" (that is, "legislative") function it provides that, with certain

exceptions, agencies must publish notice and at least permit interested

parties to submit their views in writing for agency consideration

before issuing general regulations (sec. 4). No hearings are required

by the bill unless statutes already do so in a particular case. Similarly,

in "adjudications" (that is, the "judicial" function) no agency hear-

ings are required unless statutes already do so, but in the latter case

194 ADMINISTRATIVE PROCEDURE

the mode of hearing and decision is prescribed (sec. 5). Where

existing statutes require that either general regulations (called "rules"

in the bill) or particularized adjudications (called "orders" in the bill)

be made after agency hearing or opportunity for such hearing, then

section 7 spells out the minimum requirements for such hearings,

section 8 states how decisions shall be made thereafter, and section 11

provides for examiners to preside at healings and make or participate

in decisions.

While the administrative power and procedure provisions of sec-

tions 4 through 9 are law apart from court review, the provisions for

judicial review provide parties with a method of enforcing their rights

in a proper case (sec. 10). However, it is expressly provided that the

judicial review provisions are not operative where statutes otherwise

preclude judicial review or where agency action is by law committed

to agency discretion.

KINDS

OF PROVISIONS.—The bill may be said to be composed of

five typos of provisions:

1.

Those which are largely formal such as the sections setting

forth the title (sec. 1), definitions (sec. 2), and rules of con-

struction (sec. 12).

2.

Those which require agencies to publish or make available

information on administrative law and procedure (sec. 3).

3.

Those which provide for different kinds of procedures such as

rule making (sec. 4), adjudications (sec. 5), and miscellane-

ous matters (sec. 6) as well as for limitations upon sanctions

and powers (sec. 9).

4.

Those which provide more of the detail for hearings (sec. 7)

and decisions (sec. 8) as well as for examiners (sec. 11).

5.

Those which provide for judicial review (sec. 10).

The bill is so drafted that its several sections and subordinate pro-

visions are closely knit. The substantive provisions of the bill should

be read apart from the purely formal provisions and minor functional

distinctions. The definitions in section 2 are important, but they do

not indicate the scope of the bill since the subsequent provisions make

many functional distinctions and exceptions. The public informa-

tion provisions of section 3 are of the broadest application because,

while some functions and some operations may not lend themselves

to formal procedure, all administrative operations should as a matter

of policy be disclosed to the public except as secrecy may obviously

be required or only internal agency "housekeeping" arrangements

may be involved. Sections 4 and 5 prescribe the basic requirements

for the making of rules and the adjudication of particular cases. In

each case, where other statutes require opportunity for an agency

hearing, sections 7 and 8 set forth the minimum requirements for

such hearings and the agency decisions thereafter while section 11

provides for the appointment and tenure of examiners who may

participate. Section 6 prescribes the rights of private parties in a

number of miscellaneous respects which may be incidental to rule

making, adjudication, or the exercise of any other agency authority.

Section 9 limits sanctions, and section 10 provides for judicial review.

ADMINISTRATIVE PROCEDURE

195

FIGURE

2.—Diagram of principal sections of bill

Sec.

3

PUBLIC

INFORMATION

(a) Rules

(b) Opinions

and orders

(c) Public

rec-

ords

Sec.

4

RULE MAKING

(a) Notice

(b) Procedures

(c) Effective

dates

(d) Petitions

Sec.

5

ADJUDICATION

(a) Notice

(b) Procedure

(c) Separation

of func-

tions

(d) Declara-

tory orders

Sec. 8

DECISIONS

Sec.

8

ANCILLARY

MATTERS

(a) Appear-

ance

(b) Investiga-

tions

(c) Subpenas

(d) Denials

See.

9

POWERS

AND

SANCTIONS

(a)

In

general

(b) Licenses

—

grants,

re-

vocations,

renewals

Sec. 7

HEARINGS

(a) Presiding offi-

cers

(b) Hearing powers

(c) Evidence

(d) Record

(a) Action

by sub-

ordinates

(b) Submittals

and

decisions

Sec.

10

JUDICIAL REVIEW

(a) Right

of

review

(b) Form

and

venue

(c) Renewable acts

(d)

Interim relief

(e) Scope

of

review

Sec.

11

EXAMINERS

Civil-service selec-

tion, compensa-

tion,

and

tenure

Section

1

prescribes

the

title, section

2 the

definitions,

and

section

3 the

effective dates

and rules

of

construction.

In the

above diagram,

the

first

row of

sections sets forth

the

several kinds

of

requirements, procedures, find limitations;

and the

second

row

includes

bearing

and

decision requirements where other statutes require

a

hearing. Section

10 on

judicial review relates

not

only

to

decisions made after agency hearing

but, in

appropriate

cases,

to the

exercise

of any

other administrative power

or

authority.

IV. ANALYSIS

OF

PROVISIONS

The following statements respecting each provision

of the

bill

are

designed

to

answer specific questions relating

to

language

and

objec-

tives.

Under each section

or

subsection heading there appears

an

italicized synopsis

of the

provision, followed

by one or

more para-

graphs

of

analysis

or

special comment.

A

reading

of all the

italicized

paragraphs will, therefore, afford

a

synopsis

of the

whole bill, which

is

reproduced

at

length

in

appendix

A at

page

32.

SEC.

1. TITLE.—It is

provided that the measure

may

be cited

as the

Administrative Procedure

Act.

While

a

short title

has

been deemed preferable,

it may be

noted

that

the

bill actually provides

for

both administrative procedure and

judicial review.

SEC.

2.

DEFINITIONS.—The

definitions apply

to

the remainder

of

the

bill.

196 ADMINISTRATIVE PROCEDURE

For the purpose of both simplifying the language of later provisions

and achieving greater precision, general terms of administrative law

and procedure are defined.

(a)

AGENCY.—The

word "agency" is defined by excluding legislative,

judicial, and territorial authorities and by including any

other

"author-

ity" whether or not within or subject to review by another agency. The

bill is not to be construed to repeal

delegations

of authority provided by

law. Expressly exempted from the term "agency",

except

for the public

information

requirements

of

section

3, are (1)

agencies composed

of

repre-

sentatives of parties or of organizations of parties and (2) defined war

authorities including civilian authorities functioning under temporary

or named statutes

operative

during "present hostilities."

The word "authority" is advisedly used as meaning whatever

persons are vested with powers to act (rather than the mere form

of agency organization such as department, commission, board, or

bureau) because the real authorities may be some subordinate or

semidependent person or persons within such form of organization.

In conferring administrative powers, statutes customarily do not

refer to formal agencies (such as the Department of Agriculture)

but to specified persons (such as the Secretary of Agriculture).

Boards or commissions usually possess authority which does not

extend to individual members or to their subordinates.

The bill does not repeal delegations of authority which are duly

authorized by existing law. This does not mean, however, that

delegations are effective where other provisions of the bill require

otherwise. For example, the requirement that examiners in certain

instances hear cases would supersede any existing delegations to

prosecuting officers to hear such cases.

Agencies composed of representatives of the parties or of organi-

zations of the parties to the disputes determined by them are exempted

because such agencies as presently operated do not lend themselves

to the adjudicative procedures set out in the remaining sections of the

bill. They tend to be arbitral or mediating agencies rather than

tribunals.

The exclusion of war functions and agencies, whether exercised

by civil or military personnel, affords all necessary freedom of action

for the exercise of such functions in the period of reconversion. It

has been deemed wise to exempt such functions in view of the fact

that they are rarely required to be exercised upon statutory hearing,

with which much of the bill is concerned, and the fact that they are

rapidly liquidating. It should be noted, however, that even war

functions are not exempted from the public information requirement

of section 3. "Present hostilities" means those connected with the

war brought on at Pearl Harbor in December 1941.

(b)

PERSON

AND

PARTY.—"Person''

is defined to include specified

forms of

organizations other

than

agencies.

"Party" is

defined

to include

anyone

named,

or admitted or seeking and entitled to be admitted, as a

party in any agency proceeding except that nothing in the subsection is

to be construed to prevent an agency from admitting anyone as a party

for limited purposes.

The definition of person includes both individuals and any form of

organization but advisedly excludes Federal agencies. The practice

of agencies to admit persons as parties in proceedings "for limited

purposes" is expressly preserved, but that exception does not authorize

ADMINISTRATIVE

PROCEDURE

197

any agency to ignore or prejudice the rights

of

the true or full parties

in

any proceeding.

(c)

RULE

AND

RULE

MAKING.—"Rule"

is

defined

as any

agency

statement

of

general applicability designed

to

implement, interpret,

or

prescribe law, policy, organization, procedure, or practice requirements.

"Rule making" means

agency process

for

the formulation, amendment, or

repeal

of a

rule

and

includes

any

prescription

for the

future

of

rates,

wages, financial structures,

etc., etc.

The definition

of

"rule"

is

important because

it

prescribes

the

kind

of operation that

is

subject

to

section

4

rather than section

5. The

specification

of the

activities that

are

involved

in

rule making

is

included

in

order

to

comprehend them beyond

any

possible question.

They

are

defined

as

rules

to the

extent that, whether

of

general

or

particular applicability, they formally prescribe

a

course

of

conduct

for

the

future rather than merely pronounce existing rights

or lia-

bilities.

It

should

be

noted that rule making

is

exempted from some

of

the

general requirements

of

sections

7 and 8

relating

to the

details

of hearings and decisions.

(d)

ORDER AND

ADJUDICATION.—"Order" means the final disposition

of

any

matter,

other

than rule making but including licensing, whether or

not affirmative, negative,

or

declaratory

in

form. "Adjudication"

means

the

agency process

for

theformulation of an

order.

The term "order"

is

defined

to

exclude rules. "Licensing"

is

specifically included

to

remove

any

possible question

at the

outset.

Licenses involve

a

pronouncement

of

present rights

of

named parties

although they

may

also prescribe terms

and

conditions

for

future

observance.

It

should

be

noted, however, that licensing

is

exempted

from some

of the

provisions

of

sections

5, 7, and 8

relating

to

hearings

and decisions.

(e)

LICENSE

AND LICENSING.—"License"

is

defined

to

include

any

form

of

required official permission such

as

certificate, charter,

etc.

"Licensing"

is

defined

to

include agency process respecting

the

grant,

renewal, modification, denial,

revocation,

etc.,

of

a

license.

This definition supplements subsection

(d).

Later provisions

of the

bill distinguish between initial licenses

and

renewals

or

other licensing

proceedings.

A

further distinction might have been drawn between

licenses

for a

term, such

as

radio licenses,

and

those

of

indefinite

duration, such

as

certificates

of

convenience

and

necessity.

(f)

SANCTION

AND

RELIEF.—"Sanction"

is

defined

to

include

any

agency prohibition, withholding

of

relief,

penalty, seizure, assessment,

requirement, restriction, etc.

"Relief" is

defined

to

include

any

agency

grant,

recognition,

or

other beneficial

action.

These definitions

are

mainly relevant

to

section

9 on

sanctions

and

powers

and to

section

10 on

judicial review.

The

purpose

of the

subsection

is to

define exhaustively every possible form

of

legitimate

administrative power

or

authority.

(g)

AGENCY PROCEEDING

AND

ACTION.—"Agency proceeding"

is

defined

to

mean

any

agency process defined

in

the foregoing subsections

(c),

(d),

or (e). For

the

purpose of

section

10

on

judicial

review,

"agency

action"

is

defined

to

include

an

agency rule, order, license, sanction,

relief,

or

the equivalent

or

denial

thereof,

and failure

to act.

The term "agency proceeding"

is

specially defined

in

order

to

simplify

the

language

of

subsequent provisions

and to

assure that

all

forms

of

administrative procedure

or

authority

are

included.

The

198

ADMINISTRATIVE PROCEDURE

term "agency action" brings together previously defined terms

in

order

to

simplify

the

language

of the

judicial review provisions

of

section 10

and to

assure

the

complete coverage

of

every form

of

agency

power, proceeding, action,

or

inaction.

SEC.

3.

PUBLIC

INFORMATION.—From

the

public information

pro-

visions

of

section

3

there

are exempted

matters

(1)

requiring

secrecy

in the

public interest

or (2)

relating solely

to the

internal management

of an

agency.

The public information requirements

of

section

3 are in

many ways

among

the

most important, far-reaching,

and

useful provisions

of the

bill.

For the

information

and

protection

of the

public wherever

lo-

cated, these provisions require agencies

to

take

the

mystery

out of

administrative procedure

by

stating

it. The

section

has

been drawn

upon

the

theory that administrative operations

and

procedures

are

public property which

the

general public, rather than

a few

specialists

or lobbyists,

is

entitled

to

know

or to

have

the

ready means

of

knowing

with definiteness

and

assurance.

The introductory clause states

the

only general exceptions.

The

first, which excepts matters requiring secrecy

in the

public interest,

is

necessary

but

is

not

to

be construed

to

defeat the purpose

of

the remain-

ing provisions.

It

would include confidential operations

in

any agency,

such

as

some

of the

aspects

of the

investigating

or

prosecuting func-

tions

of the

Secret Service

or

Federal Bureau

of

Investigation,

but no

other functions

or

operations

in

those

or

other agencies. Closely

re-

lated

is the

second exception,

of

matters relating solely

to

internal

agency management, which

may not be

construed

to

defeat other

provisions

of the

bill

or to

permit withholding

of

information

as to

operations which remaining provisions

of the

section

or of the

whole

bill require

to be

public

or

publicly available.

(a)

RULES.—Every

agency

is

required

to

publish

in

the

Federal Register

its

(1)

organization,

(2)

places

of

doing business with

the

public,

(3)

methods

of

rule making

and

adjudication including

the

rules

of

practice

relating

thereto,

and (4)

such substantive rules

as it

may frame

for the

guidance

of

the public.

No

person

is in any

manner

to be

required

to

resort

to

organization or

procedure

not

so published.

Since

the

bill leaves wide latitude

for

each agency

to

frame

its own

procedures, this subsection requiring agencies

to

state their organi-

zation

and

procedures

in the

form

of

rules

is

essential

for the

informa-

tion

of the

public.

The

publication must

be

kept

up to

date.

The

enumerated classes

of

informational rules must also

be

separately

stated

so

that,

for

example, rules

of

procedure will

be

separate from

rules

of

substance, interpretation,

or

policy.

The

effect

of any

one of

the first three classifications

of

required rule making

is

that agencies

must also publish their internal delegations

of

authority.

The sub-

section forbids secrecy

of

rules binding

or

applicable

to the

public,

or

of delegations

of

authority.

The

requirement that

no one

shall

"in

any manner"

be

required

to

resort

to

unpublished organization

or

procedure protects

the

public from being required

to

pursue remedies

that

are not

generally known.

(b)

OPINIONS

AND ORDERS.—Agencies are

required

to

publish

or,

pursuant to rule, make

available

to public inspection

all

final opinions

or

orders

in

the adjudication

of

cases except those

held confidential for

good

cause

and

not cited as precedents.

ADMINISTRATIVE PROCEDURE 199

Rule making results in published material in the Federal Register

as set forth in subsection (a), but in the case of adjudication there is

no standard, general, and official medium of publication. Some

agencies publish sets of some of their decisions, but otherwise the

public is not informed as to how and where they may see decisions

or consult precedents. Requiring each agency to formulate and

publish a rule respecting access to their final opinions and orders will

give the general public notice as to how such information may be

secured. While the subsection does not mention "rulings"—which

are neither rules nor orders but are general interpretations, such as

the opinions of agency counsel—if authoritative, they would be

covered by the fourth category in subsection (a) of this section.

(c)

PUBLIC

RECORDS.—Except as statutes may require otherwise or

information may be held

confidential

for good cause, matters of

official

record

are to

be

made

available

to persons properly and directly

concerned

in

accordance

with rules to

be

issued by the agency.

This provision supplements subsections (a) and (b). The require-

ment of an agency rule on the availability of official records is inserted

for the same purpose as in subsection (b). In many cases, the interest

of the person seeking access to the record will be determinative.

Agencies should classify data in order to specify what may be disclosed

and what may not; and they must in any case provide how and where

applications for information may be made, how they will be deter-

mined, and who will do so. Refusals of information would be subject

to the requirements of section 6 (d).

SEC.

4.

RULE

MAKING.—

The

introductory

clause exempts

from all

of

the requirements of

section

4 any rule making

so

far as

there

are

involved

(1) military, naval,

or

foreign affairs functions or (2) matters relating

to agency management or personnel or to public property, loans, grants,

benefits, or

contracts.

These exceptions would not, of course, relieve any agency from

requirements imposed by other statutes. The phrase "foreign affairs

functions," used here and in some other provisions of the bill, is not

to be loosely interpreted to mean any function extending beyond the

borders of the United States but only those "affairs" which so affect

relations with other governments that, for example, public rule

malting provisions would clearly provoke definitely undesirable inter-

national consequences. The exception of matters of management or

personnel would operate only so far as not inconsistent with other

provisions of the bill relating to internal management or personnel.

The exception of proprietary matters is included because the prin-

cipal considerations in most such cases relate to mechanics and inter-

pretations or policy, and it is deemed wise to encourage and facilitate

the issuance of rules by dispensing with all mandatory procedural

requirements. None of these exceptions, however, is to be taken as

encouraging agencies not to adopt voluntary public rule making pro-

cedures where useful to the agency or beneficial to the public. The

exceptions merely confer a complete discretion upon agencies to decide

what, if any, public rule making procedures they will adopt in a given

situation within their terms. It should be noted, moreover, that the

exceptions apply only "to the extent" that the excepted subjects are

directly involved.

(a)

NOTICE.—General

notice of proposed rule making must be pub-

lished in the Federal Register and must include (1) time, place, and

200

ADMINISTRATIVE PROCEDURE

nature of

proceedings,

(2) reference to authority under which

held,

and

(3) terms, substance, or issues involved. However, except where notice

and hearing is required by some other statute, the subsection does not

apply to rules other than those of

substance

or

where

the

agency

for

good

cause finds (and incorporates the finding and reasons therefor in the

published rule) that notice and public procedure are impracticable,

unnecessary, or contrary to the public interest.

Agency notice must be sufficient to fairly apprise interested parties

of the issues involved, so that they may present responsive data or

argument relating thereto. The subsection governs the application

of the public procedures required by the next subsection, since those

procedures only apply where notice is required by this subsection.

Agencies are given discretion to dispense with notice (and conse-

quently with public proceedings) in the case of interpretative rules,

general statements of policy, or rules of agency organization, pro-

cedure, or practice. This does not mean, however, that agencies

should not—where useful to them or helpful to the public—undertake

public procedures in connection with such rule making. The exemp-

tion of situations of emergency or necessity is not an "escape clause"

in the sense that any agency has discretion to disregard its terms or

the facts. A true and supported or supportable finding of necessity

or emergency must be made and published. "Impracticable" means

a situation in which the due and required execution of the agency

functions would be unavoidably prevented by its undertaking public

rule-making proceedings. "Unnecessary" means unnecessary so far

as the public is concerned, as would be the case if a minor or merely

technical amendment in which the public is not particularly interested

were involved. "Public interest" supplements the terms "imprac-

ticable" or "unnecessary"; it requires that public rule-making pro-

cedures shall not prevent an agency from operating and that, on the

other hand, lack of public interest in rule making warrants an agency

to dispense with public procedure. It should be noted that where

authority beneficial to the public does not become operative until a

rule is issued, the agency may promulgate the necessary rule immedi-

ately and rely upon supplemental procedures in the nature of a public

reconsideration of the issued rule to satisfy the requirements of this

section. Where public rule-making procedures are dispensed with,

the provisions of subsections (c) and (d) of this section would never-

theless apply.

(b)

PROCEDURES.—After

such notice, the agency must afford

interested

persons an opportunity to participate in the rule making at least to the

extent of submitting written data, views, or argument; and, after consider-

ation of such presentations, the agency must incorporate in any rules

adopted

a

concise general

statement of

their

basis and purpose. However,

where other statutes require rules to be made after hearing, the require-

ments of sections 7 and 8 (relating to public hearings and decisions

thereon)

apply in place of

the

provisions of this subsection.

This subsection states, in its first sentence, the minimum require-

ments of public rule making procedure short of statutory hearing.

Under it agencies might in addition confer with industry advisory

committees, consult organizations, hold informal "hearings," and the

like.

Considerations of practicality, necessity, and public interest as

discussed in connection with subsection (a) will naturally govern the

agency's determination of the extent to which public proceedings

ADMINISTRATIVE PROCEDURE 20 1

should go. Matters of great import, or those where the public sub-

mission of facts will be either useful to the agency or a protection to

the public, should naturally be accorded more elaborate public pro-

cedures. The agency must analyze and consider all relevant matter

presented. The required statement of the basis and purpose of rules

issued should not only relate to the data so presented but with reason-

able fullness explain the actual basis and objectives of the rule.

(c)

EFFECTIVE

DATES.—The required publication or service of any

substantive rule must be made not less than 30 days prior to its

effective

date except (1) as

otherwise

provided by the

agency

for

good

cause found

and published

or

(2) in the

case

of rules

recognizing

exemption

or

relieving

restriction, interpretative rules, and statements of policy.

This subsection does not provide procedures alternative to notice

and other public proceedings required by the prior subsections of this

section. Nor does it supersede the provisions of subsection (d) of this

section. Where public procedures are omitted as authorized in cer-

tain cases, subsection (c) does not thereby become inoperative. It

will afford persons affected a reasonable time to prepare for the effective

date of a rule or rules or to take any other action which the issuance of

rules may prompt. While certain named kinds of rules are not neces-

sarily subject to the deferred effective date provided, it does not

thereby follow that agencies are required to make such excepted types

of rules operative with less notice or no notice but, instead, agencies

are given discretion in those cases to fix such future effective date as

they may find advisable. The other exception, upon good cause found

and published, is not an "escape clause" which may be arbitrarily

exercised but requires legitimate grounds supported in law and fact by

the required finding. Moreover, the specification of a 30-day deferred

effective date is not to be taken as a maximum, since there may be

cases in which good administration or the convenience and necessity

of the persons subject to the rule reasonably requires a longer period.

(d)

PETITIONS.—Every

agency is required to accord any interested

person

the

right

to

petitionfor

the

issuance, amendment,

or

repeal

of

a

rule.

This subsection applies not merely to effective rules existing at any

time but to proposed or tentative rules. Where the latter are pub-

lished, agencies should receive petitions for modification because that

is one of the purposes of publishing proposed or tentative rules.

Where such petitions are made, the agency must fully and promptly

consider them, take such action as may be required, and pursuant to

section 6 (d) notify the petitioner in case the request is denied. The

agency may either grant the petition, undertake public rule making

proceedings as provided by subsections (a) and (b) of this section, or

deny the petition. The taking or denial of action would have the

same effect and consequences as the taking or denial of action where,

under presently existing legislation, the equivalent of a right of

petition is recognized in interested persons. The mere filing of a

petition does not require an agency to grant it, or to hold a hearing,

or engage in any other public rule making proceedings. The refusal

of an agency to grant the petition or to hold rule making proceedings,

therefore, would not per se be subject to judicial reversal. However,

the facts or considerations brought to the attention of an agency by

such a petition might be such as to require the agency to act to

prevent the rule from continuing or becoming vulnerable upon

20 2

ADMINISTRATIVE PROCEDURE

judicial review, through declaratory judgment or other procedures

pursuant to section 10.

SEC.

5.

ADJUDICATIONS.—The

various subsequent provisions of sec-

tion 5 relating to adjudications apply only where the case is otherwise

required by statute to be determined upon an agency hearing except that,

even in that case, the following classes of operations are expressly not

affected: (1) Cases subject to trial de novo in court, (2)

selection

or tenure

of public

officers

other than examiners, (3) decisions resting on inspec-

tions, tests, or

elections,

(4) military, naval, and foreign affairs functions

(5)

cases

in which an

agency

is acting for a court,

and

(6)

the

certification

of

employee

representatives.

The general limitation of this section to cases in which other statutes

require the agency to act upon or after a hearing is important. All

cases are nevertheless subject to sections 2, 3, 6, 9, 10, and 12 so far as

those are otherwise relevant.

The numbered exceptions remove from the operation of the

section even adjudications otherwise required by statute to be made

after hearing. The first, where the adjudication is subject to a judicial

trial de novo, is included because whatever judgment the agency makes

is effective only in a prima facie sense at most and the party aggrieved

is entitled to complete judicial retrial and decision. The second,

respecting the selection and tenure of officers other than examiners, is

included because the selection and control of public personnel has been

traditionally regarded as a discretionary function which, if to be over-

turned, should be done by separate legislation. The third exempts

proceedings resting on inspections, tests, or elections because those

methods of determination do not lend themselves to the hearing

process. The fourth exempts military, naval, and foreign affairs func-

tions for the same reasons that they are exempted from section 4; and,

in any event, rarely if ever do statutes require such functions to be

exercised upon hearing. The fifth, exempting cases in which an agency

is acting as the agent for a court, is included because the administrative

operation is subject to judicial revision in toto. The sixth, exempting

the certification of employee representatives such as the Labor Board

operations under section 9 (c) of the National Labor Relations Act,

is included because these determinations rest so largely upon an election

or the availability of an election. It should be noted that these excep-

tions apply only "to the extent" that the excepted subject is involved

and, it may be added, only to the extent that such subjects are directly

involved.

(a)

NOTICE.—Persons

entitled to notice of an agency hearing are to

be duly and timely informed of (1) the time, place, and nature of the

hearing, (2) the legal authority and jurisdiction under which it is to be

held,

and (3) the matters of fact and law

asserted.

Where private per-

sons are the, moving parties, respondents must give prompt notice of

issues

controverted

in law or fact; and in other cases the agency may

require,

responsive

pleading. In fixing the times and places for hearings

the agency must give due regard to the convenience and necessity of

the parties.

The specification of the content of notice, so far as legal authority

and the issues are concerned, does not mean that prior to the com-

mencement of the proceedings an agency must anticipate all develop-

ments and all possible issues. But it does mean that, either by the

formal notice or otherwise in the record, it must appear that the party

ADMINISTRATIVE PROCEDURE 203

affected has had ample notice of the legal and factual issues with due

time to examine, consider, and prepare for them. The second

sentence of the subsection applies in those cases where the agency

does not control the matter of notice because private persons are the

moving parties; and in such cases the respondent parties must give

notice of the issues of law or fact which they controvert so that the

moving party will be apprised of the issues he must sustain. The

purpose of the provision is to simplify the issues for the benefit of

both the parties and the deciding authority. The last sentence,

requiring the convenience and necessity of the parties to be consulted

in fixing the times and places for hearings, includes an agency party

as well as a private party; but the agency's convenience is not to out-

weigh that of the private parties and, while the due and required

execution of agency functions may be said to be paramount, that con-

sideration would be controlling only where a lack of time has been

unavoidable or a particular place of hearing is indispensable and does

not deprive the private parties of their full opportunity for a hearing.

(6)

PROCEDURE.—The

agency is required first to afford parties an

opportunity for the settlement or adjustment of issues (where time, the

nature of

the,

proceeding, and the public interest permit) followed, to the

extent that issues are not so

settled,

by hearing and decision under sections

7 and 8.

The preliminary settlement-by-consent provision of this subsection

is of the greatest importance. Such adjustments may go to the

whole or any part of any case. The limitation of the requirement to

cases in which "time, the nature of the proceeding, and the public

interest permit" does not mean that formal proceedings, to the

exclusion of prior opportunity for informal settlement, lie in the

discretion of any agency irrespective of the facts, legal situation

presented, or practical aspects of the case. It does not mean that

agencies have an arbitrary choice, or that they may consult their

mere preference or convenience. It is intended to exempt only

situations in which, for example, (1) time is unavoidably lacking, (2)

the nature of the proceeding is such that for example (as in some forms

of rule making) the great number of parties or possible parties makes

it unlikely that any adjustment could be reached, and (3) the ad-

ministrative function requires immediate ex petition in order to protect

the tangible and demonstrable requirements of public interest.

(c)

SEPARATION

OF FUNCTIONS.—Officers who preside at the taking

of evidence must make the decision or recommended decision in the case.

They may not consult with any person or party except openly and upon

notice, save in the disposition of customary ex parte matters, and they

may not be made subject to the supervision of prosecuting officers. The

latter may not participate, in the decisions except as witness or counsel in

public proceedings. However, the subsection is not to apply in deter-

mining applications for initial licenses or the past reasonableness of

rates; nor does it apply to the top agency or members

thereof.

The gist of the subsection is that no investigating or prosecuting

officer shall directly or indirectly in any manner influence or control

the operations of hearing and deciding officers, except as a participant

in public proceedings, and even then in no different fashion than the

private parties or their representatives. "Ex parte matters author-

ized by law" means passing on requests for adjournments, continu-

ances,

filing of papers, and so forth. The exemption of applications

90600—46

14

20 4 ADMINISTRATIVE PROCEDURE

for initial licenses frees from the requirements of the subsection such

matters as the granting of certificates of convenience and necessity

which are of indefinite duration, upon the theory that in most

licensing cases the original application may be much like rule making.

The latter, of course, is not subject to any provision of section 5. The

exemption of cases involving "the past reasonableness of rates" (if

triable de novo on judicial review they would be exempted in any

event) is made for the same reason. There are, however, some

instances of either kind of case which tend to be accusatory in form

and involve sharply controverted factual issues. Agencies should

not apply the exceptions to such eases, because they are not to be

interpreted as precluding fair procedure where it is required.

A further word may be said as to the last exemption—of the agency

itself or the members of the board who comprise it. Such a provision

is required by the very nature of administrative agencies, where the

same authority is responsible for both the investigation-prosecution

and the hearing and decision of cases. There, too, the exemption is

not to be taken as meaning that the top authority must reserve to

itself both prosecuting and deciding functions. To be sure it is

ultimately responsible for all functions committed to it, but it may

and should confine itself to determining policy and should delegate

the actual supervision of investigations and initiation of cases to

responsible subordinate officers.

(d)

DECLARATORY

ORDERS.—Every

agency

is authorized in its sound

discretion to issue

declaratory

orders with the same effect as other orders.

This subsection does not mean that any agency empowered to issue

orders may issue declaratory orders, because it is limited by the intro-

ductory clauses of section 5. Thus, such orders may be issued only

where the agency is empowered by statute to hold hearings and the

subject is not expressly exempted by the introductory clauses of this

section.

Agencies are not required to issue declaratory orders merely because

request is made therefor. Such applications have no greater effect

than they now have under existing comparable legislation. "Sound

discretion," moreover, would preclude the issuance of improvident

orders. The administrative issuance of declaratory orders would be

governed by the same basic principles that govern declaratory judg-

ments in the courts.

SEC.

6.

ANCILLARY

MATTERS.—The provisions of

section

6

relating

to

incidental or

miscellaneous

rights, powers, and

procedures

do

not

override

contrary provisions in

other

parts of

the

bill.

The purpose of this introductory exception, which reads "except as

otherwise provided in this act," is to limit, for example, the right of

appearance provided in subsection (a) so as not to authorize improper

ex parte conferences during formal hearings and pending formal deci-

sions under sections 7 and 8.

(a)

APPEARANCE.—Any

person compelled to appear in person

before

any agency or its representative is entitled to counsel. In other cases,

every

party may appear in person or by

counsel.

Sofar as

the

responsible

conduct of public business permits, any interested person may appear

before

any

agency

or

its

responsible officers

at any time for

the

presentation

or adjustment of any matter. Agencies are to proceed with

reasonable

dispatch to conclude any matter so presented, with due

regard

for the

convenience

and necessity of

the

parties. Nothing in the

subsection

is to

ADMINISTRATIVE PROCEDURE

205

be

taken as

recognizing

or

denying

the

propriety of

nonlawyers representing

parties.

This subsection is designed to confirm and make effective the right

of interested persons to appear themselves or through or with counsel

before any agency. The word "party" in the second sentence is to be

understood as meaning any person showing the requisite interest in

the matter, since the subsection applies in connection with the exercise

of any agency authority whether or not formal proceedings are avail-

able.

The phrase ''responsible officers", as used here and in some other

provisions, both includes all officers or employees who really determine

matters or exercise substantial advisory functions and excludes those

whose duties are merely formal or mechanical. The third sentence

does not require agencies to give notice to all who may be affected,

but merely to receive the presentations of those who seek to make

them. The qualifying words in the third sentence—which read

"so far as the responsible conduct of public business permits"—

preclude the undue harassment of agencies by numerous petty appear-

ances by or for the same party in the same case; but they do not confer

upon agencies a discretion to emasculate the subsection or preclude

interested persons from presenting fully and before any responsible

officer or employee their cases or proposals in full. The reference to

"stop-order or other summary actions" emphasizes the necessity for

an opportunity for full informal appearance where normal and formal

hearing and decision requirements are not applicable or are inadequate.

The requirement that agencies proceed "with reasonable dispatch to

conclude any matter presented" is a statement of legal requirement

that no agency shall in effect deny relief or fail to conclude a case by

mere inaction.

The final sentence provides that the subsection shall not be taken

to recognize or deny the right of nonlawyers to be admitted to prac-

tice before any agency, such as the practitioners before the Interstate

Commerce Commission. The use of the word "counsel" means

lawyers. While the subsection does not deal with the matter ex-

pressly, the committee does not believe that agencies are justified in

laying burdensome admission requirements upon members of the bar

in good standing before the courts. The right of agencies to pass

upon the qualifications of nonlawyers, however, is expressly recog-

nized and preserved in the subsection.

(6)

INVESTIGATIONS.—Investigative

process is not to be issued or

enforced

except

as authorized by law. Persons

compelled

to submit data

or evidence are entitled to retain or, on payment of costs, to procure

copies

except

that in nonpublic

proceedings

a witness may for

good

cause

be limited to inspection of the official transcript.

This section is designed to preclude "fishing expeditions" and

investigations beyond the jurisdiction or authority of an agency.

It applies to any demand, whether or not a formal subpena is actually

issued. "Nonpublic investigatory proceeding" means those of the

grand jury kind in which evidence is taken behind closed doors.

The limitation, for good cause, to inspection of the official transcript

is deemed necessary where evidence is taken in a case in which prose-

cutions may be brought later and it is obviously detrimental to the

due execution of the laws to permit copies to be circulated. In those

cases the witness or his counsel may be limited to inspection of the

relevant portions of the transcript. Parties should in any case have

20 6

ADMINISTRATIVE PROCEDURE

copies or an opportunity for inspection in order to assure that their

evidence is correctly set forth, to refresh their memories in the case

of stale proceedings, and to enable them to be advised by counsel.

They should also have such copies whenever needed in legal or ad-

ministrative proceedings.

(c)

SUBPENAS.—Where

agencies are by law authorized to issue sub-

penas, parties may secure them upon request and upon a statement or

showing of

general relevance

and

reasonable

scope if the agency rules so

require. Where a party contests a subpena, the court is to inquire into

the situation and,

so

far as the subpena is found in

accordance

with law,

issue an order requiring the production of the

evidence

under penalty of

contempt for failure then to do so.

This provision will assure private parties the same access to sub-

penas as that available to the representatives of agencies. It will

also prevent the issuance of improvident subpenas or action by an

agency requiring a detailed, unnecessary, and burdensome showing of

evidence which might fall into the hands of the party's adversaries or

investigators and prosecutors (who in any event should not have

access to such papers directly or indirectly). The subsection con-

stitutes a statutory limitation upon the issuance or enforcement of

subpenas in excess of agency authority or jurisdiction. This does

not mean, however, that courts should enter into a detailed examina-

tion of facts and issues which are committed to agency authority in

the first instance, but should, instead, inquire generally into the legal

and factual situation and be satisfied that the agency could possibly

find that it has jurisdiction. The subsection expressly recognizes the

right of parties subject to administrative subpenas to contest their

validity in the courts prior to subjection to any form of penalty for

noncompliance.

(d)

DENIALS.—Prompt

notice is to be given of denials of

requests

in

any agency

proceeding,

accompanied by a simple statement of grounds.

This subsection affords the parties in any agency proceeding, whether

or not formal or upon hearing, the right to prompt action upon their

requests, immediate notice of such action, and a statement of the

actual grounds therefor. The latter should in any case be sufficient

to apprise the party of the basis of the denial and any other or further

administrative remedies or recourse he may have. A statement of

the actual grounds need not be made "in affirming a prior denial or

where the denial is self-explanatory." However, prior denial would

satisfy the subsection requirement only where the grounds previously

stated remain the actual grounds and sufficiently notify the party as

set forth above. A self-explanatory denial must meet the same test;

that is, the request must be in such form that its mere denial fully

informs the party of all he would otherwise be entitled to have

stated.

SEC.

7.

HEARINGS.—Section

7 relating to agency hearings applies

only

where

hearings are required by sections 4 or 5.

As heretofore stated in connection with sections 4 and 5, the bill

requires no hearings unless other statutes contain such a requirement

in particular cases of either rule making or adjudication. This