University of Mary Washington University of Mary Washington

Eagle Scholar Eagle Scholar

Student Research Submissions

Spring 5-2-2018

The U.S. War on Drugs in Latin America: What is the Method to The U.S. War on Drugs in Latin America: What is the Method to

the Madness? the Madness?

Kendall Parker

Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.umw.edu/student_research

Part of the Political Science Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Parker, Kendall, "The U.S. War on Drugs in Latin America: What is the Method to the Madness?" (2018).

Student Research Submissions

. 247.

https://scholar.umw.edu/student_research/247

This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by Eagle Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion

in Student Research Submissions by an authorized administrator of Eagle Scholar. For more information, please

contact archives@umw.edu.

!

Kendall Parker

The U.S. War on Drugs in Latin America:

What is the Method to the Madness?

Table of Contents

!"#$% & ' ( #!% " )****************************************************************************************************************************************************)+!

,-(./$%'"&)************************************************************************************************ *******************************************************)+!

0-1%$)'*2*)2'334562!&7)#-(#!(283%4!(!72)*********************************************************************************************)9!

"#$%&'$(&)*!+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++!,!

&*("#%&'(&)*!++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++!,!

%&-.$* ( /&* 0!%#10!(#$22&'3&*0!)#0$*&4$(&)*-!5%()-6!++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++!7!

$*%"$*!&*&(&$(&8"!+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++!9!

:/$*!')/).;&$!++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++!< !

.=#&%$!&*&(&$(&8"!++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++!>!

)(?"#!&*&(&$(&8"-!$*%!:#)0#$.-!++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++!>!

7::7(#!;7"722)%:)'*2*)2'334 5 62!&7)#-(#!(283%4!(!72)*********************************************************************)<!

4!#7$-#'$7)$7;!7=)**************************************************************************************************************************************)+>!

;1#"$1'#$(&'!&*"#(&$!+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++!@7!

%)."-(&'!:)/&(&'-!++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++!@<!

?"0".)*&'!-($(1-!++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++!@<!

?53%#?7272):%$0'4-#!%")-"&)&-#-)(%447(#!%")***********************************************************************)+<!

?A:)(?"-&-!@B!;1#"$1'#$(&'!&*"#(&$!?$-!%#&8"*!(?"!')*(&*1$(&)*!)2!$!-1::/AC-&%"!2)'1-!)2!(?"!

D$#!)*!%#10-+ !+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++!@E!

?A:)(?"-&-!FB!8)("#!:#"2"#"*'"!&*2/1"*'"-!:)/&'A!%"'&-&)*-!#"0$#%&*0!$*(&C%#10!/$D-+!+++++++++++++++++!F<!

?A:)(?"-&-!GB!!1+-+!-1::/AC-&%"!:)/&'&"-!&*!/$(&*!$."#&'$!?$8"!;""*!')*(&*1"%!$-!$!."'?$*&-.!

(?#)10?!D?&'?!()!.$&*($&*!#"0&)*$/!?"0".)*AH!$-!D"//!$-!$((".:(&*0!()!'1#;!(?"!-1::/A!)2!

&//&'&(!%#10-+!+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++!GG!

Mexico'.....................................................................................................................................................................................'35!

Colombia'................................................................................................................................................................................'36!

Peru'..........................................................................................................................................................................................'40!

Bolivia'.....................................................................................................................................................................................'41!

&!2('22!%")*********************************************************************************************************************************************************)9@!

;1#"$1'#$(&'!&*"#(&$!+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++!,F!

%)."-(&'!:)/&(&'-!++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++!,,!

?"0".)*&'!-($(1-!++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++!,7!

2&*$/!#"-1/(-!+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++!,<!

(%"(4'2!%")*******************************************************************************************************************************************************)9<!

!

!

!

!!

1

Introduction

Albert Einstein is credited with defining insanity as doing the same thing over and over

again and expecting different results. Based on this definition, the U.S. War on Drugs in Latin

America is insane. For over four decades, U.S. policymakers have continued to implement the

same types of supply-side policies, which academic researchers widely posit as failing to achieve

policy goals both domestically and abroad. Neither the production, supply, or transit of illegal

drugs has been reduced, nor has domestic demand decreased. Furthermore, the U.S. has spent

over $1 trillion on interdiction policies that cost taxpayers over $51 billion annually (Coyne &

Hall, 2017). Costly supply-side policies that do not achieve goals present a conundrum that begs

resolution. Why has the United States continued to pursue a counterdrug strategy in Latin

America that has been largely futile?

Answering this question is the goal of this paper. In order to do so, this paper will first

provide background that defines the U.S. War on Drugs. It will also describe key supply-side

tactics and policies. Additionally, it aims to demonstrate the overall ineffectiveness of the war

and present existing schools of thought as to why the U.S. has continued to implement failing

policies in Latin America. The schools of thought will then be used to articulate competing

hypotheses. The hypotheses will be tested through empirical research in order to determine the

explanatory power of each as it relates to the continuity of U.S. counterdrug policy in Latin

America.

Background

The United States adopted an anti-drug campaign when former President Richard Nixon

officially declared a “War on Drugs” in 1971. Nixon regarded illegal drugs as “public enemy

!

!

!!

2

number one,” presumably due to an increase in recreational drug use in the 1960s. However, the

War on Drugs may have been launched as a political assault against certain groups, specifically

African Americans and hippies, as indicated by John Ehrlichman, a top advisor to Nixon

(LoBianco, 2016). Regardless of true motivation, concern over the negative effects of domestic

drug use on society and the economy began to increase. Powerful international drug

organizations, most prominently the Medellín cartel, also posed a threat at the time. Due to these

concerns, former President Ronald Reagan declared drug trafficking a national security threat in

1986 (Bagley & Tokatlian, 1992, pp. 215-216). This declaration initiated the U.S. securitization

of drugs (Vorobyeva, 2015, p. 47).

The Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988 created the Office of National Drug Control Policy

(ONDCP). The ONDCP is also referred to as the “drug czar” office and operates as advisor to

the president on issues related to drug control. It prepares the “National Drug Control Strategy,”

which is an annual report summarizing the current administration’s plans to decrease illicit drug

use, production, trafficking, narcotics-related violence and crime, and associated health risks

(The White House, Office of National Drug Control Policy). The “National Drug Control

Strategy 1989” reinforced U.S. securitization efforts, by maintaining that most American citizens

agreed that drugs were the most pressing national security threat at the time (Vorobyeva, 2015, p.

48).

The crack cocaine epidemic and related violence in the mid-1980s were pivotal in the

formation of many hard-line anti-drug policies in the United States (Youngers and Rosin, 2005,

p. 2). Determination of narcotics trafficking as a national security issue resulted in tougher drug

laws, greater military involvement, heightened interdiction efforts at the borders and overseas,

and broader anti-drug measures in Latin American and other source and transit countries (Bagley

!

!

!!

3

& Tokatlian, 1992, p. 216). Latin America and the Caribbean provided almost all of the cocaine

and marijuana, as well as 40 percent of the heroin, smuggled into the U.S. on an annual basis,

which heightened concerns for national security (Bagley & Tokatlian, 1992, p. 216). Thus, the

War on Drugs developed a supply-side focus.

At the conceptual level, the War on Drugs is a U.S. governmental campaign aimed at

reducing significantly the production and availability of illicit drugs via policies of prohibition

(Youngers & Rosen, 2005, p. 1). Domestically, the preferred methods against the production,

distribution, and use of illicit drugs include strict laws, improved law enforcement, and increased

incarceration (Youngers & Rosen, 2005, p. 3). Overseas, these prohibition policies have

generated extensive military aid and intervention to curb drug production and intercept

transnational shipments, in order to reduce the supply of illicit drugs (Youngers & Rosen, 2005,

p. 3). The majority of federal funding has been spent on the supply side, based on the economic

theory that limiting supply makes narcotics trafficking costlier, thereby driving up prices for

American consumers and making a drug habit harder to maintain. “Proponents of drug

prohibition claim that such policies reduce drug-related crime, decrease drug-related disease and

overdose, and are an effective means of disrupting and dismantling organized criminal

enterprises” (Coyne & Hall, 2017, p. 1). In reality, however, prohibition policies do not achieve

the intended goals both domestically and overseas. This paper focuses on continual supply-side

efforts that are specific to countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, which have not only

proven to be ineffective, but also produce negative consequences.

!

!

!!

4

Major U.S. Supply-Side Tactics/Policies

Eradication

U.S. policy in Latin America and the Caribbean aims to reduce supply by subduing illicit

drug production. Eradication, or physical destruction, of crops is a strategy used by the United

States to decrease the production of illicit drugs in source countries. Eradication may occur by

force or be encouraged voluntarily by the following three methods: manual plant removal, the

use of herbicides, or biological control using pathogens or predators (Crop Control Policies

(Drugs), 2001). The Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs

(INL) provides assistance to Colombia, Peru, and Guatemala for their own aerial and manual

eradication programs (U.S. Department of State). The coca leaf and opium poppy, used to

produce cocaine and heroin respectively, have been prime targets (Youngers & Rosin, 2005, p.

3). Marijuana has also been a target of crop control measures.

The “National Drug Control Strategy 1991” recommends that manual or herbicidal

eradication efforts, crop substitution, alternative income options, and developmental projects that

heighten living standards and produce income take place when feasible (Crop Control Policies

(Drugs), 2001). U.S. government officials assert that eliminating drugs at the source through

eradication is the most cost-effective supply-side strategy. The source of illicit drugs is viewed as

the most commercially vulnerable link in the grower-to-user chain (Crop Control Policies

(Drugs), 2001). “Our international counternarcotics programs target the first three links of the

grower-to-user chain: cultivation, processing, and transit” (Youngers & Rosin, 2005, p. 3).

Interdiction

U.S. policy also aims to reduce supply through interdiction. Drug interdiction involves

attempts to interrupt illegal drugs in the process of being smuggled by land, air, or sea from

!

!

!!

5

producing countries into the United States (Joint Chiefs of Staff, 2010). The U.S. Army, Air

Force, and Navy, along with Coast Guard counternarcotics teams, are regularly deployed to track

down and capture drug smugglers (The Associated Press, 2013). Modern technology aids in their

efforts. For instance, the Coast Guard uses drones to locate vessels transporting drugs (Lopez &

Goodman, 2017). The U.S. military also trains Latin American militaries and law enforcement

agents, in order to build a large, well-equipped network to stem the flow of illicit drugs coming

into the U.S. from Latin America (The Associated Press, 2013).

Interdiction aims to make the drug business costlier for traffickers. Increased costs to

drug traffickers result in higher retail prices, which should, in turn, decrease consumption by

Americans. Additionally, interdiction efforts attempt to increase the difficulty of smuggling and

adequately punish the guilty parties (Drug Interdiction, 2001). These efforts supply intelligence

that is used to identify, target, and eventually dismantle drug trafficking organizations (DTOs).

Dismantling Drug Trafficking Organizations (DTOs)

In the early 1980s, the U.S. military became increasingly involved in interdiction efforts

to help law enforcement agencies attack the threat of powerful DTOs (Seelke, Wyler, Beittel, &

Sullivan, 2011). Many arrests and extraditions, as well as the seizure of drugs, guns, and cash

have resulted from U.S. efforts to dismantle these complex organizations. U.S. federal agencies

and allies share intel and investigatory leads to exploit the vulnerabilities of DTOs (Executive

Office of the President of the United States, 2015, p. 74). In addition, the U.S. has channeled aid,

by providing training and equipment, so Latin American countries may help in the fight.

U.S. efforts to dismantle DTOs include attacking their financial infrastructures.

According to the “National Drug Control Strategy 2015,” U.S. law enforcement and intelligence

agencies identify and target illicit financial activities and money laundering networks utilized by

!

!

!!

6

DTOs (p. 74). The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), for example, maintains

interagency liaisons with the U.S. Treasury to connect the flow of illicit drug proceeds to DTOs

and facilitate the dissemination of information (Drug Enforcement Administration). It also works

with the financial services industry and its domestic and foreign law enforcement counterparts to

share financial information, exchange intelligence, and conduct joint investigations (Drug

Enforcement Administration). National financial program initiatives target the monetary flow

back to international drug supply sources (Drug Enforcement Administration, n.d.). Financial

Investigation Teams (FITs) carry out these initiatives, as well as conduct more complex financial

investigations (Drug Enforcement Administration). DEA Special Agents work in liaison with the

ONDCP, Department of Defense (DOD), and the Intelligence Community. The DEA has

financial units in many foreign countries that aid in international money laundering

investigations (Drug Enforcement Administration). Indeed, many governmental agencies work to

identify and trace illicit drug proceeds in order to uncover money laundering activities to help

dismantle DTOs.

Andean Initiative

The supply-side tactics described above receive funding from federal anti-drug policies,

such as the Andean Initiative. Former President George H. W. Bush is responsible for launching

the Andean Initiative in 1989, as part of his administration’s national strategy to intensify the

fight against illegal drugs. Bush’s national strategy was formed in response to the growing power

of Colombian DTOs, especially the Medellín and Cali cartels (Vorobyeva, 2015, p. 48). The U.S.

had been supplying anti-drug aid to Colombia, Peru, and Bolivia, the world’s largest cocaine

producers, since the early 1970s, but an increase in domestic cocaine consumption and the

powerful DTOs in the 1980s elicited more aid to these countries (Vorobyeva, 2015, p. 48).

!

!

!!

7

The Andean Initiative allocated $2.2 billion over five years to limit the production of

drugs in the Andean region. Its main goal was to empower Latin American military and police

forces to perform counterdrug initiatives, by providing U.S. training and support to those willing

to do so (Youngers & Rosin, 2005, p. 3). The Andean Initiative document refers to the real and

widespread damage and violence connected to the illicit drug trade, thus providing justification

for U.S. foreign actions and policies in Latin America (Vorobyeva, 2015, p. 48).

Plan Colombia

The militarization of counterdrug policies that began with the Andean Initiative

significantly increased throughout the 1990s. Joint efforts by the U.S. and Colombia managed to

break down the Medellín and Cali cartels, but smaller DTOs surfaced and insurgents became

involved in drug trafficking (Vorobyeva, 2015, p. 51). As a result, there was a major increase in

coca cultivation and production in Colombia, despite a large-scale herbicide spraying program

implemented at the request of the United States (Isacson, 2005, p. 45).

The Colombian drug and security crisis was the basis for Plan Colombia, an initiative

announced in 1999 by Colombian President Andrés Pastrana. Plan Colombia was a six-year $7.5

billion aid package designating $3.5 billion to be provided by the international community

(Vorobyeva, 2015, p. 51). Former President Bill Clinton promoted shared responsibility with

Colombia in the drug war. He claimed that contributions to Plan Colombia would serve the

purposes of drug interdiction and democracy development in Colombia (Vorobyeva, 2015, p.

53). However, the adopted version of Plan Colombia indicated increased militarization. U.S.

assistance was primarily in the form of military training and equipment, even though President

Pastrana proposed a comprehensive plan for national reconstruction (Vorobyeva, 2015, p. 53).

Former President George W. Bush’s administration continued to approve aid under Plan

!

!

!!

8

Colombia. It repackaged military and economic aid for Colombia and neighboring countries

under the Andean Regional Initiative (ARI), thus maintaining efforts that began under Clinton’s

administration (Isacson, 2005, p. 46).

After the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the focus of Plan Colombia shifted. U.S. counterdrug aid

was redirected toward “narco-guerrilla” and “narco-terrorism” efforts (Vorobyeva, 2015, p. 54).

The terrorism threat created an environment that allowed for greater securitization of illicit drugs

by the United States. Plan Colombia existed in its initial form until 2015. Peace talks between the

Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), a guerrilla

movement, resulted in a new program called Peace Colombia, but the U.S. maintains a heavy

presence in the country.

Mérida Initiative

The collapse of major drug cartels in Colombia increased the significance of Mexican

DTOs as a national security threat because Mexico became the main transit location for cocaine

exported from the Andean Region (Vorobyeva, 2015, p. 55). Former President George W. Bush

agreed with Mexico’s President Felipe Calderón’s hard-line approach to drug trafficking, which

was funding extensive military and law enforcement efforts (Vorobyeva, 2015, p. 55). In 2007,

both presidents agreed to the development of the Mérida Initiative, a cooperative security

initiative with Mexico and Central America designed to combat drug trafficking, transnational

crime, and terrorist threats in the Western Hemisphere (U.S. Department of State, 2007). This

initiative continued the trend of a supply-side focus for foreign drug control policies in Latin

America, as the majority of U.S. aid was designated for law enforcement and military equipment

(Vorobyeva, 2015, p. 56).

Other Initiatives and Programs

!

!

!!

9

In 2010, under former President Barack Obama’s Administration, Congress split the

portion of the Mérida Initiative designated for Central America into a separate initiative (Seelke,

Wyler, Beittel, & Sullivan, 2011). The Central America Regional Security Initiative (CARSI)

supplies training and equipment to combat security threats to the seven Central American

countries of Belize, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Panama.

Also in 2010, Obama designated the following Caribbean nations as prominent drug

producer and transit countries for illicit drugs coming into the United States: the Bahamas, the

Dominican Republic, Haiti, and Jamaica (Seelke, Wyler, Beittel, & Sullivan, 2011). The

Caribbean Basin Security Initiative (CBSI) extends increased military and economic aid to the

region to fight transnational crime and narcotics trafficking, as well as for social justice and

education programs (Seelke, Wyler, Beittel, & Sullivan, 2011).

Additionally, the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) is responsible for a wide array of

counternarcotics assistance programs for Latin America and the Caribbean. The DOD provides

training and equipment to security forces participating in anti-drug efforts through the U.S.

Southern Command (SOUTHCOM) and the U.S. Northern Command (NORTHCOM), which

are regional combatant commands (Seelke, Wyler, Beittel, & Sullivan, 2011).

Effectiveness of U.S. Supply-Side Tactics/Policies

U.S. counterdrug efforts have focused on combating illicit drugs at the source for

decades, so it is important to evaluate the effectiveness of supply-side tactics and the policies that

fund them. Eradication and interdiction efforts, combined with efforts to dismantle DTOs and

halt money laundering activities, have yielded some positive results in the Andean region. For

example, crop-control programs and successful interdiction efforts that began in the late 1980s in

!

!

!!

10

Peru and Bolivia caused coca cultivation to decrease to all-time lows. Furthermore, U.S. anti-

drug policies have managed to dismantle DTOs, such as the Medellín and Cali cartels in

Colombia.

However, “partial victories” of the drug war have caused negative consequences, like the

“balloon effect” (Bagley, 2015, p. 8). Scholars and policy experts define the “balloon effect” as a

government’s effort to impede drug cultivation or trafficking in one country, triggering it to

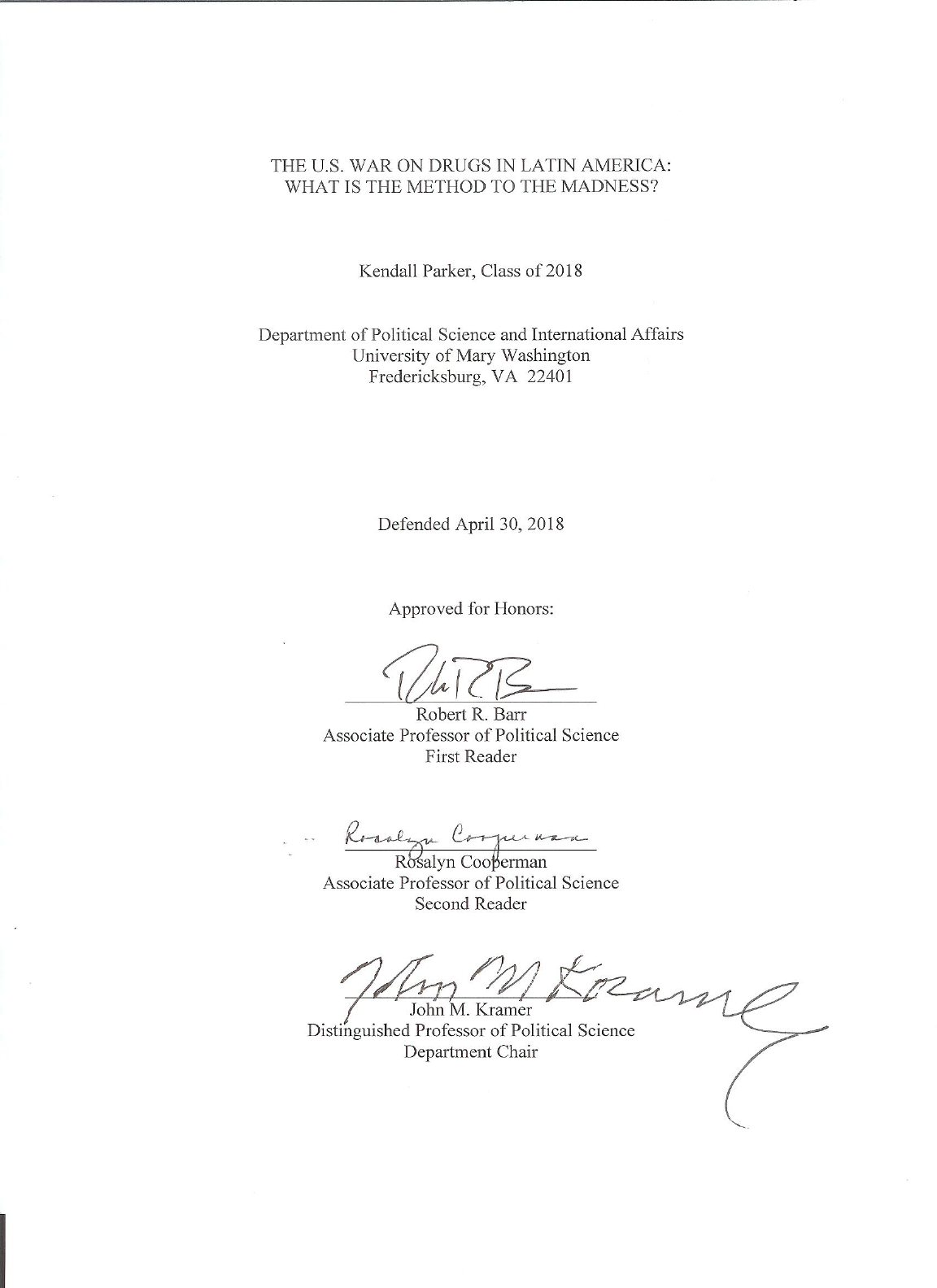

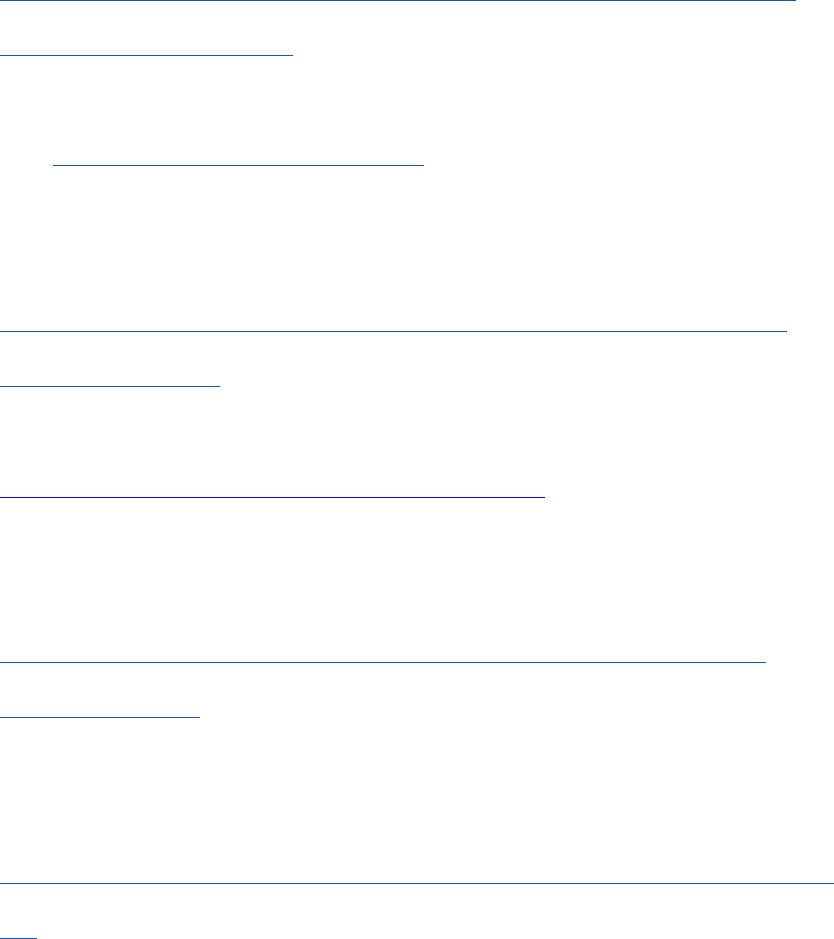

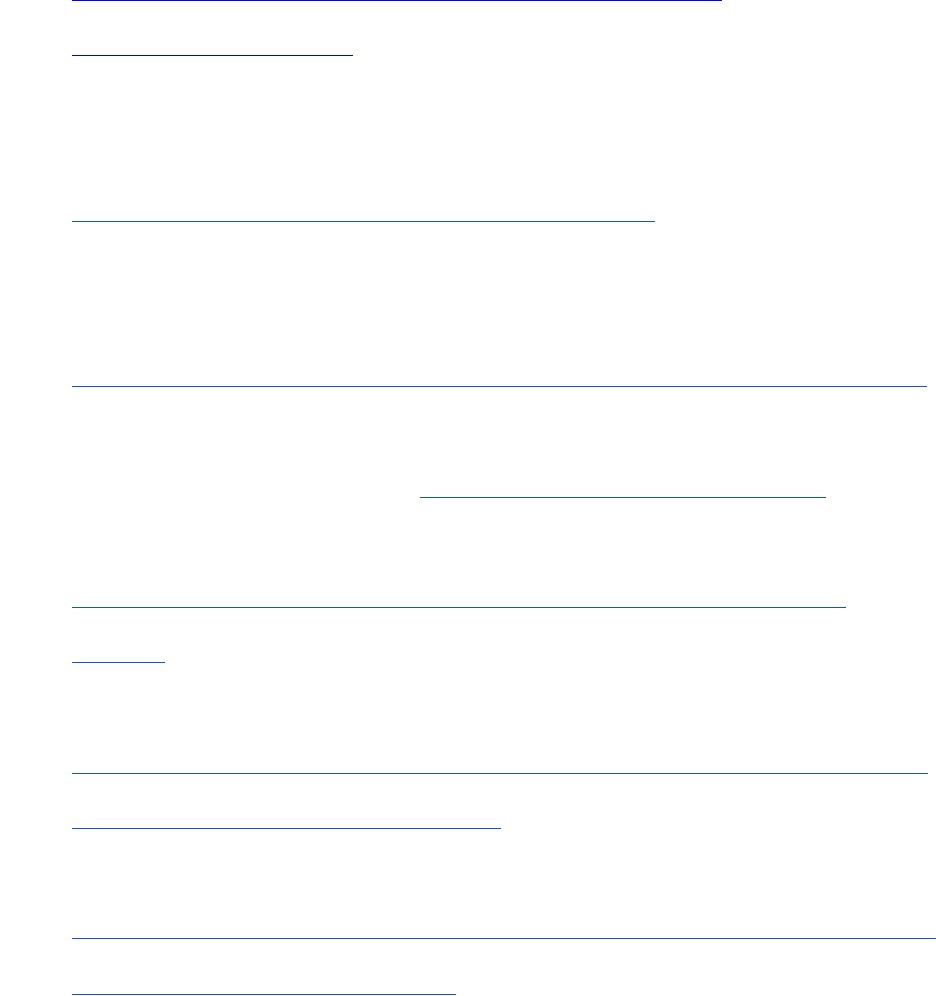

“balloon out” to other countries or regions (Bagley & Rosen, 2015, p. 412). Figure 1 below

provides evidence of the “balloon effect.”

Figure 1:

!

2ABCDEF)$ABGE)HIJ)-CDE

The graph shows coca production in Peru, Bolivia, and Colombia combined, as well as a

breakdown by individual country, during the 1980s and 1990s. An abrupt shift in coca

cultivation from Peru and Bolivia to Colombia is apparent in the mid-1990s, while total coca

!

!

!!

11

production in the region remained largely consistent with a gradual increase (Rouse & Arce,

2006). Focused U.S. anti-drug efforts to combat cultivation in Peru and Bolivia caused it to

“balloon out” into Colombia (Rouse & Arce, 2006). The drug industry effectively restructured its

operations and began growing more coca in Colombia. Additionally, coca cultivation statistics

vary within countries, due to “partial victories” from eradication efforts. Increases in these

efforts cause significant drops in coca cultivation initially, but growers adjust over time by

replanting, scattering their plots, or growing in ungoverned areas, which causes cultivation to

regain momentum (Isacson, 2016). Overall, coca cultivation shifts from one area to another

within a country and also “balloons out” to other countries, which negates any progress made

from governmental efforts.

Another negative consequence is the “cockroach effect,” or the “fragmentation of

criminal drug-trafficking organizations in a manner akin to turning on the lights in a kitchen and

witnessing the cockroaches disperse” (Bagley & Rosen, 2015, p. 415). A multitude of smaller

DTOs were quick to take advantage of the drug business left behind when the larger cartels in

Colombia were dismantled. Additionally, the established smuggling routes of the Medellín and

Cali cartels, which were basically shut down by law enforcement and military efforts, were

abandoned for new routes through Panama and Central America (Bagley, 2015, p. 8). Over time,

smuggling routes just shift from one area to another and new personnel fill the void when DTOs

are demolished.

Drug-related money laundering also presents a challenge to U.S. governmental agencies.

According to the DEA, through the combined efforts of all federal agencies only about $1 billion

of the estimated $65 billion that Americans spend annually on illicit drugs is seized per year in

the United States (Tokatlian, 2013). Therefore, confiscation is limited as an effective tool for

!

!

!!

12

curbing drug-related money laundering. Overall, U.S. anti-drug policies in Latin America and the

Caribbean are failing to make a serious dent in illicit drug production or narcotics trafficking.

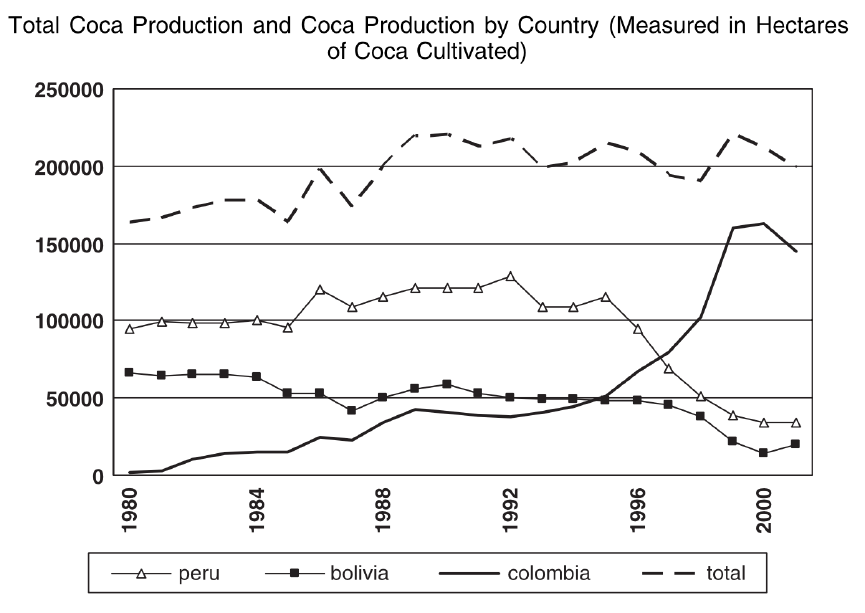

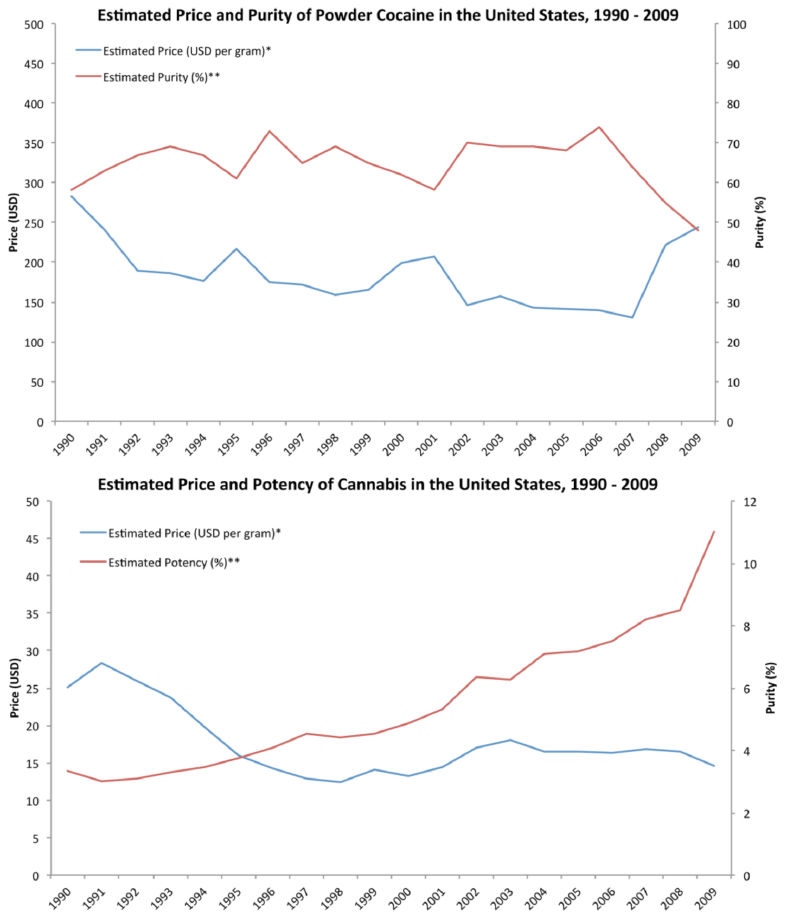

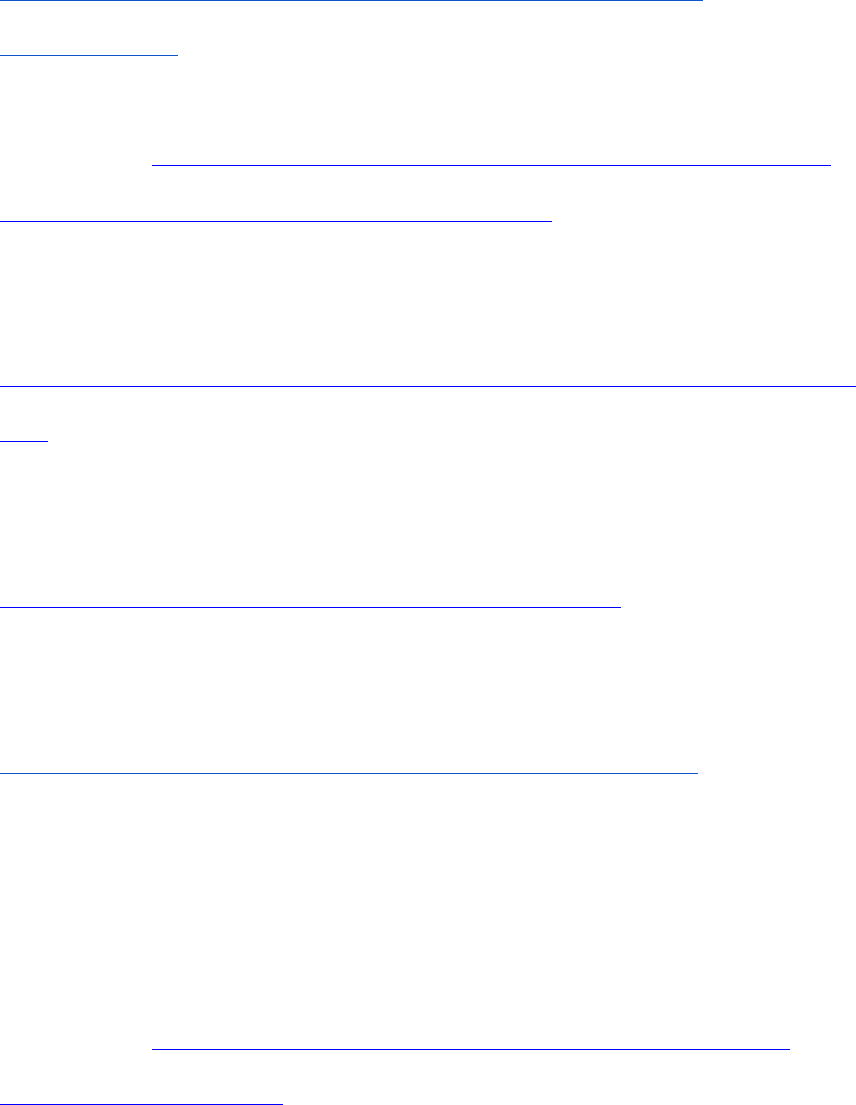

Most importantly, despite an increase in investment in supply-reduction efforts based on

enforcement and aimed at interrupting global drug supply, illicit drug prices have overall

decreased while drug purity has overall increased since 1990 (Werb, Kerr, Nosyk, et al., 2013, p.

1). Data from the DEA’s System To Retrieve Information from Drug Evidence (STRIDE)

surveillance system reveal that the retail street prices of heroin, cocaine, and cannabis declined

between 1990 and 2007, when adjusted for inflation and purity (Werb, Kerr, Nosyk, et al., 2013,

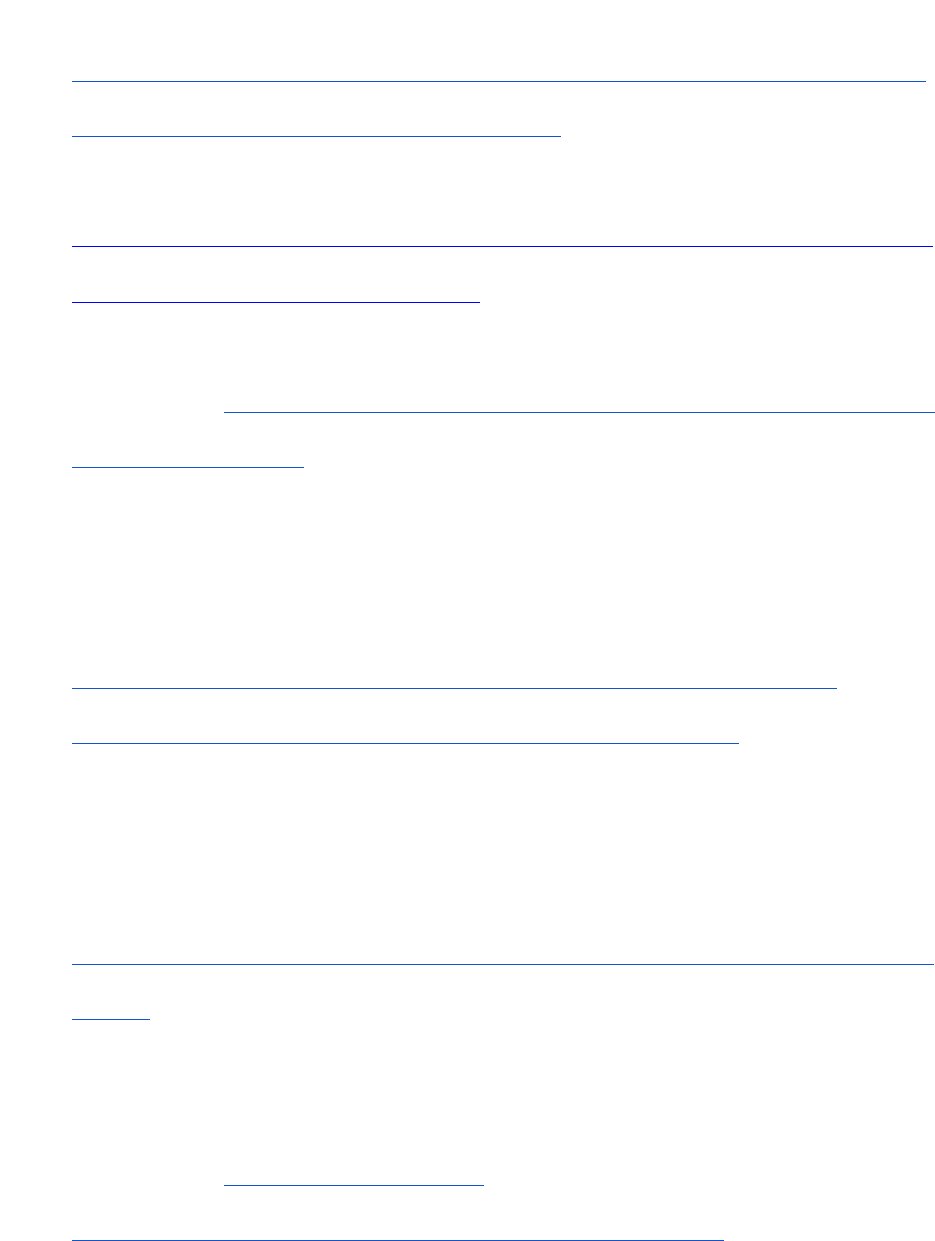

p. 2). The statistics are detailed in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2:

!

!

!!

13

2ABCDEF)=ECKL).ECCL)"AGMNL)@O+P

The retail prices of heroin, cocaine and cannabis in the U.S. decreased 81 percent, 80 percent,

and 86 percent, respectively (Werb, Kerr, Nosyk, et al., 2013, p. 4). Over the same time frame,

the purity of heroin and cocaine, and the potency of cannabis in the U.S. increased by 60 percent,

11 percent, and 161 percent, respectively (Werb, Kerr, Nosyk, et al., 2013, p. 2).

Furthermore, an increasing amount of illicit drug seizures over time has failed to reduce

supply. From 1990 to 2010, data from STRIDE show that the amount of cannabis seized by the

!

!

!!

14

DEA both in, and destined for, the U.S. increased 465 percent, the amount of cocaine seized

fluctuated but decreased overall by 49 percent, and the amount of heroin seized increased 29

percent (Werb, Kerr, Nosyk, et al., 2013, p. 4). From 1990 to 2007, the United Nations Office on

Drugs and Crime (UNODC) reports that cocaine seizures in the Andean region decreased 81

percent, but seizures of coca leaf increased 188 percent (Werb, Kerr, Nosyk, et al., 2013, p. 5).

“In summary, longitudinal illegal drug surveillance systems demonstrate a general global pattern

of falling drug prices and increasing drug purity and potency, alongside a relatively consistent

pattern of increasing seizures of illegal drugs” (Werb, Kerr, Nosyk, et al., 2013, p. 7). It is clear

from this data that eradication and interdiction efforts are unsuccessful, because illicit drug prices

are not increasing and supply is plentiful.

The lack of effectiveness of anti-drug tactics and policies in Latin America is especially

concerning because these efforts generate extremely high social costs, to include rising drug

usage rates, overcrowded prisons, and flourishing organized crime and violence (Youngers,

2011). For decades the U.S. has continued to be the country with the largest consumption rate of

illicit drugs, with a rough value that may top as high as $150 billion per year (Bagley, 2015, p.

2). Increasing law enforcement, in an attempt to make drugs costlier and more difficult to obtain,

has failed (Self, 2013). Overcrowded prisons are a negative side effect, as the number of drug

dealers incarcerated in the U.S. has increased by a factor of 15 over the last four decades (Self,

2013). In 2014, more than 50 percent of inmates in American prisons were imprisoned for drug-

related offenses and that percentage has increased fairly consistently over decades, from 16

percent in 1970 (Miles, 2014). Arresting key players, in order to dismantle DTOs, has not been

effective, but it has caused “bloody struggles for control” (Drug Policy Alliance, 2017). Ongoing

human rights issues are also a problem. In Latin American source and transit countries,

!

!

!!

15

militarization of the drug war has resulted in serious human rights violations by law enforcement

and armed forces over the years. These violations include extrajudicial executions, forced

disappearances, and violent conflict with farmers over eradication (Griggs & Zamora, 2014).

Also, law enforcement officers often disproportionately target young people, immigrants, and

sex workers, resulting in over-incarceration in the region (Griggs & Zamora, 2014).

The Latin American drug war has weakened institutions, as well. Regionally, drug-

related corruption has furthered the weakening of national and local government institutions,

judiciaries, and law enforcement (Youngers, 2005, p. 339). Additionally, scholarly case studies

have concluded that, “U.S. drug control policies have contributed to confusing military and law

enforcement functions, militarizing local police forces, and bringing the military into a domestic

law enforcement role” (Youngers, 2005, p. 340). Concerns over the failure of U.S. drug control

policies in Latin America has generated significant scholarly research as to why the United

States has continued to pursue such costly strategies.

Literature Review

Bureaucratic Inertia

A review of the literature reveals different schools of thought, such as bureaucratic

inertia, that may provide the answer to such a perplexing question (Bagley & Tokatlian 1992;

Isacson 2005; Crandall 2002, 2014). Policymakers originally designed supply-side, anti-drug

strategies based on a realist view of the international system, however bureaucratic inertia has

perpetuated them. Supporters of realism believe that threats to national security warrant the use

of all national power resources, including force (Bagley & Tokatlian, 1992, p. 216). When illicit

drugs were declared a national security threat, the U.S. began to impose its hegemonic power on

!

!

!!

16

Latin American countries (Isacson, 2005, p. 15). The realist perspective dictates that the U.S. has

both the right and obligation, as a hegemonic power, to necessitate cooperation from

subordinated states on issues like the drug war (Bagley & Tokatlian, 1992, pp. 216-217). This

realist-based protocol for responding to national security threats led to the militarization of the

War on Drugs. In turn, this militarization causes problems in the U.S. foreign policymaking

process. Specifically, many government officials are motivated to vie for anti-drug budget

operating funds that are dispersed among a large number of programs and agencies, which

inevitably keeps failed strategies from receiving the necessary reforms (Isacson, 2005, p. 16).

Such motivation can be attributed to bureaucratic inertia because officials are consumed with the

funding process for status-quo strategies.

Scholars postulate that bureaucratic pressure from within the U.S. government will

continue to prioritize the maintenance of existing drug war protocol, especially interdiction

efforts in the Andean region, mainly because the War on Drugs has become institutionalized in

the policy process (Crandall, 2002, p. 6). As a result, continuous funding of anti-drug initiatives

will be necessary. “The U.S. war on drugs has taken on a life of its own, an inertial drive that

will continue regardless of its success in actually reducing the amount of illegal drugs that enter

the United States” (Crandall, 2002, p. 7). The U.S. has employed the efforts of the U.S. Navy,

Border Patrol, Coast Guard, and DEA in international anti-drug efforts for so many years that it

is routine. Furthermore, the major objective of SOUTHCOM, despite initial resistance by the

Pentagon, is to overpower the drug war (Crandall, 2014). “There is and will continue to be an

inertial and almost impregnable military-narcotics-industrial complex, especially on the

international side of the drug war” (Crandall, 2014). While the drug war may have been launched

because illicit drugs were deemed a national security threat, the literature indicates that it has

!

!

!!

17

continued due to bureaucratic inertia. Therefore, bureaucratic inertia must be considered as a

reason for the continuation of ineffective anti-drug strategies in Latin America.

Domestic Politics

Domestic politics also appears in the literature as a guiding factor behind continued

support of failing anti-drug strategies in Latin America (Bagley & Tokatlian 1992; Youngers

2005; Kurtz-Phelan 2012). Scholars credit the built-in feature of pluralism, “short-run domestic

political criteria, partisan posturing, and electoral cycles,” as the driving force behind supply-side

anti-drug strategies, instead of a long-term cost-benefit analysis (Bagley & Tokatlian, 1992, p.

220). The democratic nature of the United States government leads to drug control policies that

are crafted with the voter in mind, as well as produce results in the short-term that can justify

budgets (Youngers, 2005, p. 341). Politicians believe that voters will more likely support them if

they appear tough on drugs versus admitting that billions of taxpayer dollars have been wasted

on failing strategies (Youngers, 2005, p. 341). Accordingly, there exists an “iron law of domestic

politics,” which postulates that voters support hard-line anti-drug policies and punish politicians

who back alternative policies (Kurtz-Phelan, 2012). The literature suggests that domestic

politics, especially the opinion of voters, must be examined as rationale behind the maintenance

of unsuccessful drug control strategies in Latin America.

Hegemonic Status

The literature also proposes that U.S. hegemony in Latin America may be a driving force

behind anti-drug policies (Stokes 2005; Draitser 2015; Reiss 2010; Alvarez 2014). U.S.

intervention in Latin American countries aims to stabilize a specified set of economic, social, and

political alignments within those countries, as well as in the international system as a whole

(Stokes, 2005, p. 122). Such stability helps maintain the dominant status of the United States in

!

!

!!

18

the international system. Therefore, U.S. policy is geared toward undermining any threats to

hegemony.

According to the literature, the War on Drugs serves as a pretext under which the U.S.

has tried to maintain its hegemonic status, but other justifications include the Cold War conflict

and terrorism (Stokes, 2005, p. 122). The U.S. has responded to recent growth in the political,

economic, and cultural independence of Latin American countries, especially Venezuela under

Hugo Chávez, with more military involvement in the region to maintain and further its

hegemonic status (Draitser, 2015). Scholars posit that furthering U.S. hegemony is an unstated

goal of the drug war.

The certification process, which became a law in 1986, acts as a tool to criminalize

challenges to the dominant status of the United States in Latin America (Reiss, 2010). It requires

the president to identify major drug-producing and trafficking countries yearly and certify that

they have effectively cooperated with international drug control agreements during the previous

12 months. Decertification allows the U.S. to impose multiple punishments, such as cutting aid

and denying trade preferences. Scholars assert that political tensions between the U.S. and Latin

American countries, such as Venezuela and Bolivia, have determined decertification, instead of

ineffective drug control (Reiss, 2010). In this way, the certification process may be used to

weaken challenges to U.S. hegemony. As the United States is currently expanding the same

failing anti-drug strategies into Central America that it has implemented in other Latin American

regions for decades, activists view this as a continued effort to maintain U.S. hegemony in the

region through force (Alvarez, 2014). Therefore, hegemonic status is worthy of testing as

motivation for continued implementation of failing supply-side strategies in the Latin American

drug war.

!

!

!!

19

Hypotheses Formulation and Data Collection

As detailed in the previous section, a review of the literature reveals three significant

schools of thought regarding the reasoning behind U.S. maintenance of a largely futile

counterdrug strategy in Latin America. Bureaucratic inertia, domestic politics, and hegemonic

status provide an underlying basis for the formulation of testable hypotheses. Hypotheses related

to these schools of thought are articulated below, followed by chosen methodology and empirical

research to test each one as it relates to the multi-decade drug war.

Hypothesis 1: Bureaucratic inertia has driven the continuation of a supply-side focus of the War

on Drugs.

For purposes of this paper, bureaucratic inertia will be defined to include all functions of

the government, not limited to executive branch agencies and departments. Hypothesis 1 will be

tested using economic data, specifically the distribution of the federal anti-drug budget between

supply reduction efforts and demand reduction efforts from 1989 to 2016. This time period

extends from publication of the first “National Drug Control Strategy” until the last finalized

budget was available. In addition, funding for the supply reduction subcategories of interdiction,

international, and domestic law enforcement will be analyzed. Lastly, congressional hearing

testimonies will be examined to establish support for bureaucratic inertia as the reason behind the

statistics.

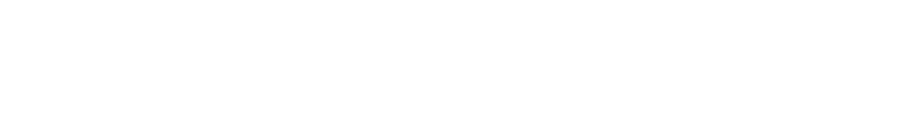

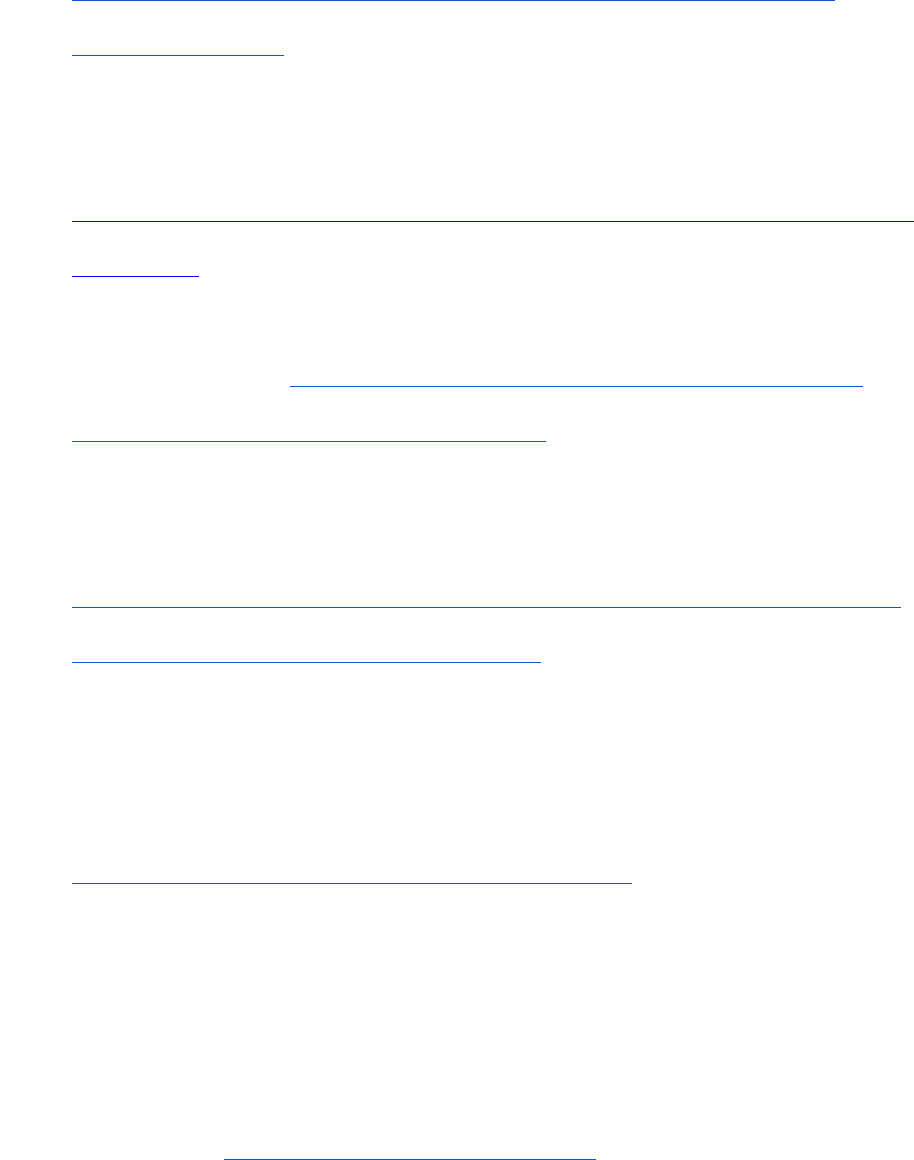

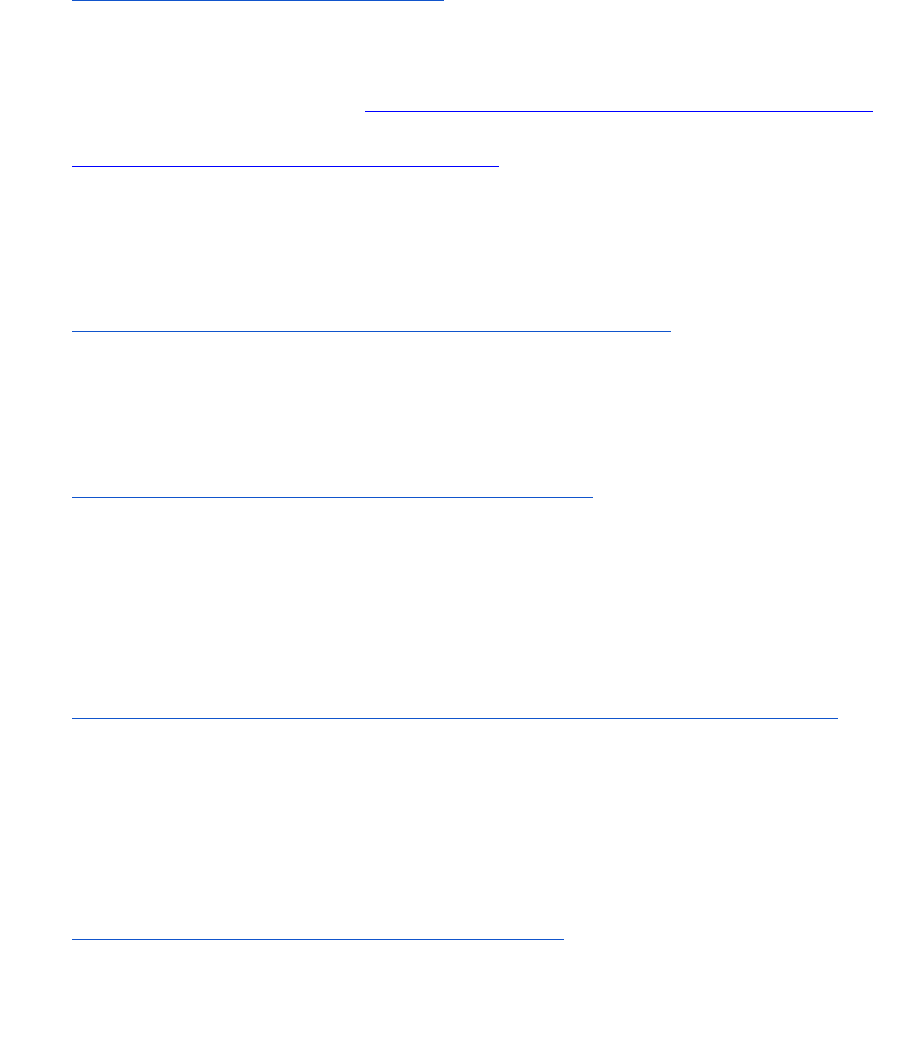

The graph below details the percentage spending ratio between supply reduction efforts

and demand reduction efforts of the federal drug control budget from 1989-2016.

!

!

!!

20

Figure 3:

2ABCDEF)#QE)=QRSE)?ABGEL)%"&(3)T+<<OU)@OO+U)@OO>U)@OO<U)@O+VW

Since 1989, supply reduction efforts have received the bulk of federal funding. The ratio of

supply-to-demand funding, at its closest, is 52 to 48. The ratio, at its furthest apart, is 71 to 29.

The average ratio from 1989 to 2016 is 62 to 38, supply to demand, demonstrating a consistently

larger portion of the federal drug control budget being spent on the supply side. There are

evident peaks in the graph that depict more demand-side funding. However, even at its closest in

2015, supply-side funding still outweighed the demand side by more than $100 million.

Therefore, the ratio of supply-to-demand funding is largely consistent overall.

Additionally, it is noteworthy to examine the budgetary spending for the interdiction,

international, and domestic law enforcement subcategories of supply-side efforts over the same

time period, which is graphed below.

!

!

!!

21

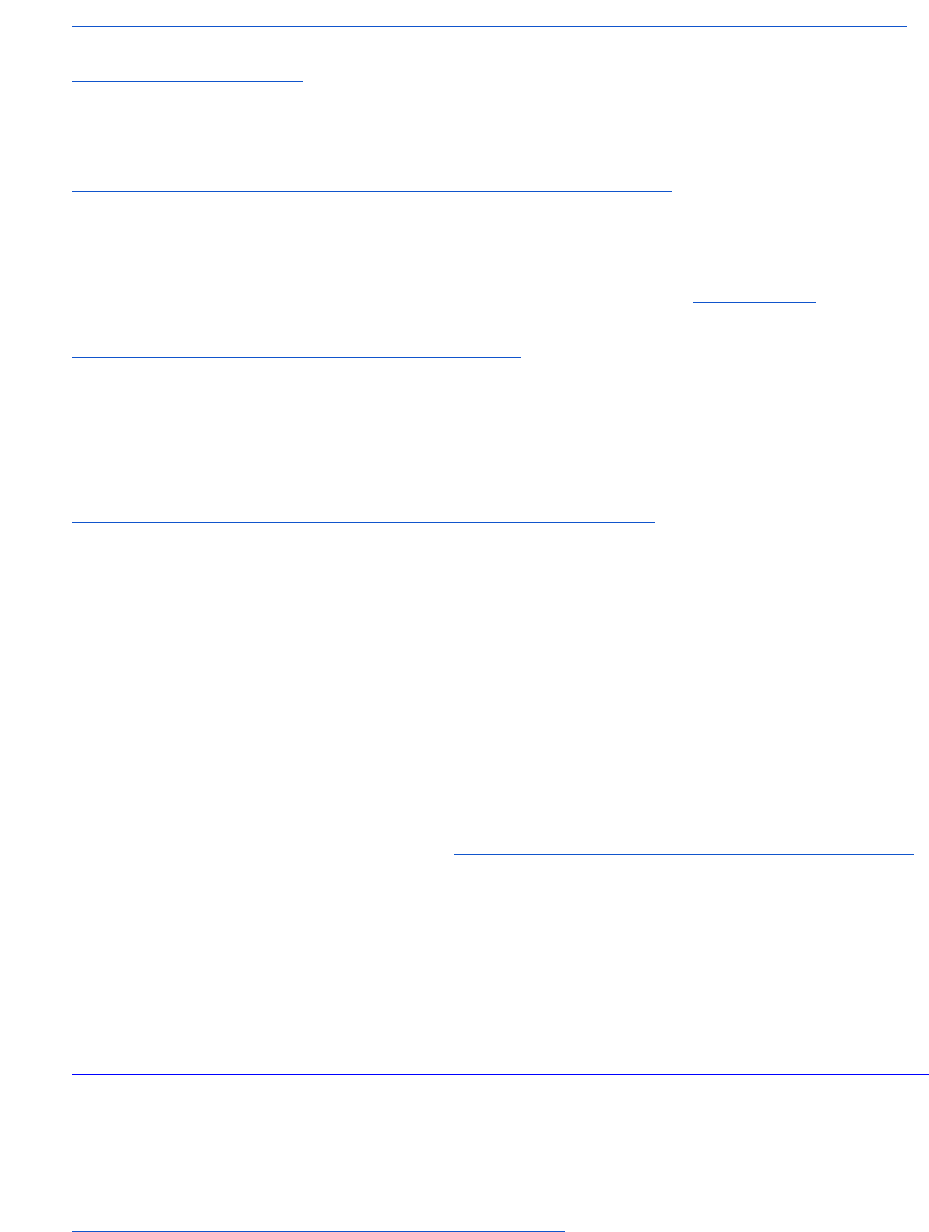

Figure 4:

)

2ABCDEF)#QE)=QRSE)?ABGEL)%"&(3)T+<<OU)@OO+U)@OO>U)@OO<U)@O+VW

There are evident peaks and valleys within all three supply-side subcategories. However, the

interdiction and international subcategories deserve the main focus due to the prevalence of these

efforts in Latin American countries. These subcategories are defined by the ONDCP to include

certain efforts. Interdiction funding contributes to federal law enforcement agencies, the military,

the intelligence community, and international allies collaborating to disrupt or intercept

shipments of illicit drugs, precursors, and associated proceeds (The White House, Office of

National Drug Control Policy, 2017). Whereas, international funding supports efforts of the U.S.

government and its international partners to dismantle DTOs, disrupt drug production and

develop holistic alternatives, fortify criminal justice systems and law enforcement in Latin

America, and fight transnational organized crime (The White House, Office of National Drug

Control Policy, 2017). Both subcategories experienced dramatic shifts in funding received over

the time period. For example, funding for Plan Colombia in 2000 drastically increased spending

on international operations from $774.7 million in 1999 to $1,619.2 million in 2000 (The White

!

!

!!

22

House, Office of National Drug Control Policy, 2005). The budget for supply reduction efforts

predominantly follows an increasing trend over the time period, with money being shifted around

to different subcategories in order to fund various projects like Plan Colombia (The White

House, Office of National Drug Control Policy, 2005).

Analysis of Figure 3 presented above supports the bureaucratic inertia school of thought

because it depicts a largely consistent ratio between supply-reduction efforts and demand-

reduction efforts over the decades-long drug war. A largely consistent ratio since 1989 indicates

that the U.S. government has not veered from its course of funding supply-side tactics over

demand-side tactics regardless of effectiveness. However, analysis of Figure 4 draws attention to

shifts within funding of the subcategories of international and interdiction that may not be fully

attributable to bureaucratic inertia.

Congressional hearing testimonies provide support for bureaucratic inertia as a reason for

the supply-side focus of federal counternarcotics funding. For example, during the 1989 hearing

“International Drug Control” before the Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Chairman Joseph

Biden declares U.S. efforts to battle DTOs as “somewhat chaotic, clumsy, and often

counterproductive…[and furthermore] we have had little success in any administration.” The

stated goal of the hearing was to review the progress, or lack thereof, in the fight against drug

cartels and identify both successes and failures (International Drug Control, 1989). Senator

Strom Thurmond then testifies as to his strong support for interdiction and highlights the need

for greater innovation in eradication methods and ways to dismantle DTOs. It is noteworthy that,

despite Biden’s recognition of counterproductive efforts in the fight against DTOs, the same

types of supply-side strategies receive support. In fact, Thurmond stresses, “I believe that with

continued efforts, we can beat the drug epidemic. However, our efforts to end this drug problem

!

!

!!

23

must be relentless” (International Drug Control, 1989). Rather than discussing change,

Thurmond calls for a ramp up of current efforts in order to obtain success.

The 1993 nomination hearing of Lee Patrick Brown to be Director of the ONDCP, before

the Committee on the Judiciary, U.S. Senate, also contains testimony that indicates bureaucratic

inertia. Brown states, “the truth is that despite having made some progress on some fronts, the

drug epidemic continues to rage...The amount of drugs entering the country continues to grow.

As one drug cartel abroad reaches its demise, another comes on to the international scene”

(Nomination of Lee Patrick Brown, 1993). Brown admits to failure of supply-side policies in

reducing the supply of drugs coming into the U.S. but does not suggest a change in focus. Instead

he later declares, “Our drug policy will always be intermixed with our concerns overseas. It must

remain a foreign policy priority. We must continue to use our diplomatic, political, economic,

enforcement, and interdiction efforts to cut the supply of drugs...” (Nomination of Lee Patrick

Brown, 1993).

During the 1995 “Effectiveness of the National Drug Control Strategy and the Status of

the Drug War” hearing before the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Oversight and

Government Reform, former Judge Robert Bonner, who also previously served as head of the

DEA, gives testimony supportive of bureaucratic inertia as well. He refers to illicit drugs as a

national security threat that should be combated with the strategies that caused sharp declines in

drug use from the mid-1980s to 1992 (Effectiveness of the National Drug Control Strategy and

the Status of the Drug War, 1995, pp. 40-41). He highlights previous success associated with

supply-side strategies. Bonner asserts,

“when it comes to drug law enforcement and interdiction, the Clinton Administration is

quick to disclaim its effectiveness...when these efforts are focused, for example from

1990 and 1992, the wholesale price of cocaine in the U.S. increased substantially...and

demand went down. A simple economics 101 lesson of supply and demand, a lesson you

!

!

!!

24

can bet the Colombian drug cartels know well” (Effectiveness of the National Drug

Control Strategy and the Status of the Drug War, 1995, p. 44).

Bonner stresses the importance of continuing with law enforcement and interdiction efforts

focused against production and distribution organizations because he views these efforts as

effective drug enforcement tactics that worked in the past (Effectiveness of the National Drug

Control Strategy and the Status of the Drug War, 1995, p. 44). However, Bonner is referring to a

relatively short time period in the course of a decades-long drug war, which has been fought

mainly with supply-side strategies that have demonstrably failed at both driving up the price of

illicit drugs and decreasing demand.

John P. Walters, former acting Director and Deputy Director of the ONDCP, echoes

Bonner’s sentiment. He testifies that the Clinton administration erred in claiming the need to

emphasize treatment and de-emphasize interdiction and effective control at the source

(Effectiveness of the National Drug Control Strategy and the Status of the Drug War, 1995,

p.18). Walters’ main point is that treatment cannot be effective with “floods of illegal drugs on

our streets,” therefore; supply-side strategies must be continually emphasized (Effectiveness of

the National Drug Control Strategy and the Status of the Drug War, 1995, p. 18). Indicative of

bureaucratic inertia, Walters calls for continuation of interdiction and eradication methods that

have proven largely futile in reducing the supply of illicit drugs coming into the U.S. from the

Latin American region.

Excerpts from the 1998 hearing entitled “Current and Projected National Security Threats

to the United States” before the Select Committee on Intelligence of the United States Senate

also convey continual U.S. commitment to supply-side strategies, due to the perceived illicit drug

threat. According to Louis Freeh, former Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI),

drug trafficking is a national security threat that caused more devastation to U.S. communities

!

!

!!

25

than extremist groups or foreign powers had at the time (Current and Projected National Security

Threats to the United States, 1998, p. 39). Freeh states that the most effective way for the FBI to

dismantle DTOs is to continue employing the Enterprise Theory of Investigation, an approach

involving long-term investigations, attacks on the command and control structures of DTOs, and

prosecutorial tools (Current and Projected National Security Threats to the United States, 1998,

pp.39-40). Freeh refers to the success in dismantling the Organization of Juan Garcia Abrego

(JGAO) in Mexico as reasoning to continue these supply-side FBI tactics (Current and Projected

National Security Threats to the United States, 1998, p. 40). Freeh’s reference to a single success

in the midst of a decades-long drug war suggests a tendency to perpetuate the status quo because

the rationale does not justify continuance of such predominantly ineffective tactics.

Another excerpt of the 1998 hearing includes a statement from Lieutenant General

Patrick Hughes, former Defense Intelligence Agency Director, which supports Hypothesis 1.

Hughes outlines some successes in reducing the supply of heroin and cocaine but acknowledges

that the reduction is not significant. He contends, however, that if the counterdrug operations

“can be sustained in the source and transit zones, it is much more likely that [they] ultimately

will reduce the supply of drugs in the United States” (Current and Projected National Security

Threats to the United States, 1998, p 173). Hughes calls for the continuation of supply-side

strategies in anticipation of eventual success.

In 2009, representatives of the U.S. Department of Justice testified before the U.S. House

of Representatives Committee on Oversight and Government Reform during a hearing entitled,

“The Rise of Mexican Drug Cartels and U.S. National Security.” The testimony refers to

Mexican drug cartels as an organized crime threat to the U.S. and responsible for “the scourge of

illicit drugs and accompanying violence” in both the U.S. and Mexico (The Rise of Mexican

!

!

!!

26

Drug Cartels and U.S. National Security, 2009, p.1). The representatives conclude that the U.S.

must build on current law enforcement strategies in order to fight the operations of the Mexican

drug cartels, such as drug trafficking, money laundering, and profit smuggling (The Rise of

Mexican Drug Cartels and U.S. National Security, 2009. p. 23). Further support of bureaucratic

inertia is present in the following excerpt, “for more than a quarter-century, the principal law

enforcement agencies in the United States have recognized that the best way to fight...criminal

organizations is through intelligence-based, prosecutor-led task forces” (The Rise of Mexican

Drug Cartels And U.S. National Security, 2009, p. 9). The Justice Department views

intelligence-based targeting as the foundation for success based on the method’s previous

success in dismantling other transnational organized criminal groups, like the mafia in the 1980s

and 1990s (The Rise of Mexican Drug Cartels And U.S. National Security, 2009). This hearing

is another example of government officials calling for the continuation of ineffective supply-side

strategies.

As outlined above, congressional hearing transcripts reveal testimonies of pertinent

government officials that support bureaucratic inertia as reasoning behind consistent supply-side

strategies. The testimonies call for continuation of such strategies after declaring them

counterproductive or by citing temporary or minimal successes. Furthermore, Bonner and Freeh

still classify illicit drugs as a national security threat over two decades after a War on Drugs was

declared, which would not be warranted if the strategies in place had achieved success.

Therefore, classifying illicit drugs as a national security threat decades later may be interpreted

as an indirect admission of failure. These official testimonies reveal an unavoidable tendency of

policymakers to perpetuate established methods in fighting illicit drug supply irrelevant to

outcome.

!

!

!!

27

Hypothesis 2: Voter preference influences policy decisions regarding anti-drug laws.

For purposes of this paper, Hypothesis 2 addresses a certain type of domestic politics,

specifically voter preference. This hypothesis will be tested using public opinion data from 1972

through 2018, such as opinions regarding the effectiveness of the drug war and funding for

foreign anti-drug strategies. Changes, or lack thereof, in counterdrug strategies relative to public

opinion will be examined. Additionally, congressional hearing testimonies will be analyzed for

references to voter preference regarding anti-drug strategies.

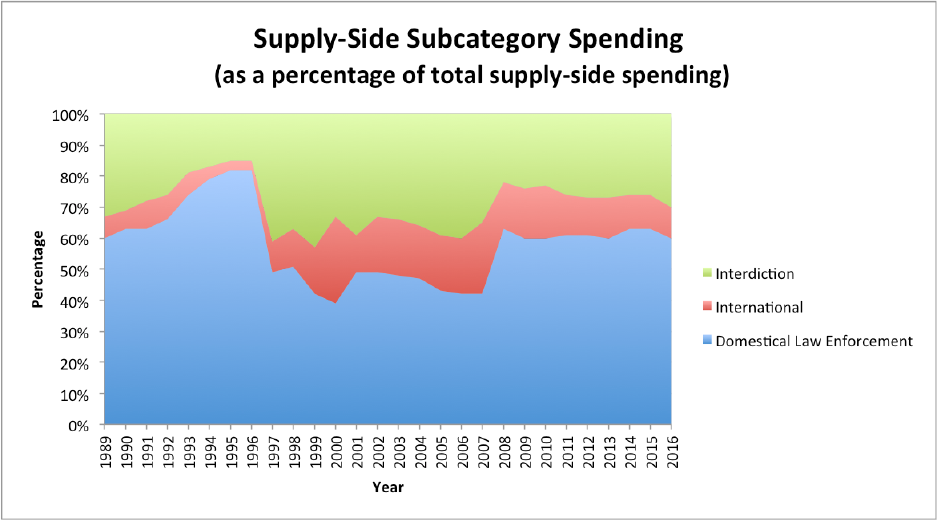

To begin with, it is important to consider public opinion regarding a basic question

relevant to testing Hypothesis 2. Voters are periodically asked whether or not America is

winning the drug war. In 2001, 74 percent of those surveyed declared that, “we are losing” (Pew

Research Center, 2001). The chart below details similar results from four separate Rasmussen

Reports surveys posing the same question.

Figure 5:

2ABCDEF)$HGXBGGEI)$EYACSG)T@O+@U)@O+PU)@O+>U)@O+ZW

A large percentage of respondents view the drug war as a failure in all four years, ranging from

75 percent to 82 percent (Rasmussen Reports, 2012; 2013; 2015; 2018). This public opinion data

does not correlate to counterdrug policy decisions, because no significant changes have been

made in the strategies to fight a war that has been viewed by the public as an overall failure since

2001.

!

!

!!

28

However, other voter preference data could possibly influence the policymaking process.

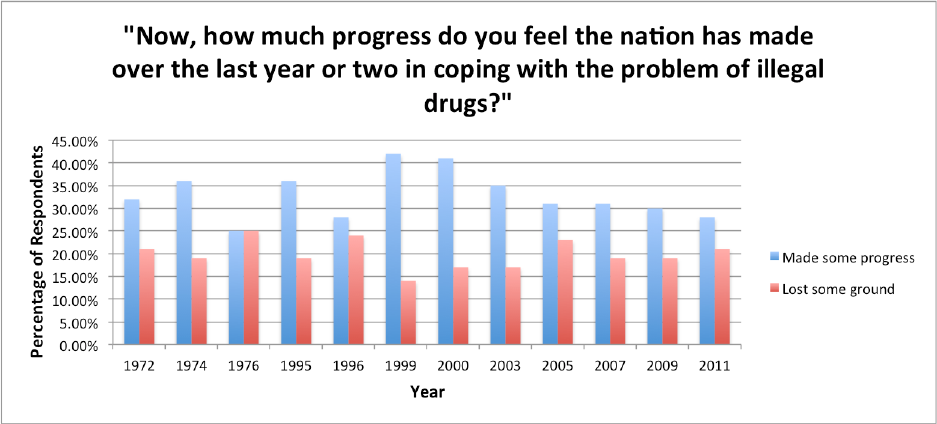

For example, the graph below highlights two noteworthy responses from a Gallup Poll conducted

certain years from 1972 to 2011.

Figure 6:

2ABCDEF)2ABCDEKAAN)A[)(CRXRIH\)1BGSRDE)2SHSRGSRDG)T@O++W

The poll prompted respondents with the following question, “Now, how much progress do you

feel the nation has made over the last year or two in coping with the problem of illegal drugs?”

(Sourcebook of Criminal Justice Statistics, 2011). The two most relevant responses indicating a

specific opinion on U.S. progress in the War on Drugs include “made some progress” or “lost

some ground.” A larger percentage of respondents claimed that the U.S. had “made some

progress” than “lost some ground” in every poll, except in 1976 when the percentages were equal

(Sourcebook of Criminal Justice Statistics, 2011). The highest disparity between those who

viewed it as “made some progress” or “lost some ground,” in 1999, is 42 percent to 14 percent,

respectively (Sourcebook of Criminal Justice Statistics, 2011). Results from this Gallup Poll

indicate that the American public viewed the counternarcotics strategy in place throughout this

time period as having success more so than not. In other words, the tactics are capable of

providing “some progress” in specific battles, but are still not winning the war. As a result,

!

!

!!

29

policymakers could interpret the results as fuel to continue on the same path, with hopes of

eventually winning the War on Drugs. However, it is also possible that policymakers could use

this data to justify their own actions, without considering it in the policymaking process at all.

Therefore, it is difficult to establish a definite link between voter preference and the decisions of

policymakers based on this poll.

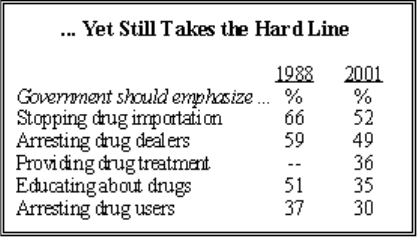

A 2001 Pew Research Center for the People and the Press survey provides a good

example of public support for supply reduction strategies. When asked the “most effective

actions the government could take to control the use of drugs,” 52 percent of respondents said

“stop the illegal importation of drugs from other countries” and 49 percent stated “arrest people

who sell illegal drugs in the country” (Office of Justice Programs, 2003). The numbers in support

of demand reduction efforts were not as high. Only 36 percent responded “provide drug

treatment programs for drug users,” and 35 percent said “educate Americans about the dangers

of using illegal drugs” (Office of Justice Programs, 2003). The 2001 data convey that the public

prioritized interdiction and arresting drug dealers over establishing more treatment programs and

decriminalization of certain drugs.

Comparison of the 2001 response percentages to those in 1988 reveals noteworthy

insight, as the chart below indicates.

Figure 7:

))) ) ) )))))2ABCDEF)3E])$EGEHCDQ)(EISEC)T@OO+W

!

!

!!

30

From 1988 to 2001, the percentages of respondents declaring all anti-drug strategies listed in the

chart as “very effective” declined. Specifically, the “very effective” rating of interdiction went

down from 66 percent to 52 percent, even though it continued to be viewed as the best

counterdrug tactic (Pew Research Center, 2001). Likewise, the effectiveness rating of “arresting

drug dealers” declined from 59 percent to 49 percent (Pew Research Center, 2001). Despite

declines in the effectiveness rating of these supply reduction tactics, a greater percentage of

Americans thought that the government should emphasize them over demand reduction efforts in

1988 and 2001 (Pew Research Center, 2001). The data suggest a correlation between voter

preference of supply-side strategies and the decisions of policy makers because more federal

funding has been funneled towards supply-side efforts since 1989 (See Figure 3).

A narrower picture of how Americans view supply-side strategies is also available from

the 2001 survey by the Pew Research Center for the People and the Press. Concerning the

amount of financial aid that the U.S. should provide to source countries, 42 percent of

respondents stated it should provide “less” than the current level and only 11 percent said that it

should provide “more” (Pew Research Center, 2001). Thirty-six percent responded that the U.S.

should provide the “same as now” (Pew Research Center, 2001). However, public opinion on

providing military assistance to drug-producing countries was less decisive, with 23 percent

agreeing that the U.S. should provide “more” and 28 percent that it should provide “less” (Pew

Research Center, 2001). Thirty-seven percent agreed that the U.S. should provide “same as now”

(Pew Research Center, 2001). It is difficult to link voter preference to policies, such as Plan

Colombia, based on this survey. Plan Colombia consisted primarily of U.S. military assistance

and generated a spike in interdiction and international funding in the years following 2001 (See

Figure 4). According to the survey, Americans were divided as to how much foreign military

!

!

!!

31

assistance should be provided to source countries and 42 percent voted for a decrease in financial

aid, as well. Therefore, public opinion was most likely not an influencing factor in decisions

regarding such counterdrug policies like Plan Colombia.

Congressional hearing testimonies provide another means to test Hypothesis 2. In the

1989 “International Drug Control” hearing, Senator Thurmond cites public opinion as backing

for intensifying supply-side strategies. Thurmond argues, “a nationwide poll released by George

Gallup and the National Drug Policy Director, William Bennett, shows that Americans are fed up

with the importation, distribution and use of illegal drugs. They want action to end this scourge”

(International Drug Control, 1989). He puts forward that Americans want drug dealers and drug

users to be prosecuted and heavily punished, plus foreign drug operations to be aggressively

pursued (International Drug Control, 1989). These statements show intent to produce a

compelling argument in favor of supply-side tactics supposedly built on the basis of U.S. public

opinion.

In the 1995 “Effectiveness of the National Drug Control Strategy and the Status of the

Drug War” hearing, Lee Brown, former director of ONDCP, defends President Clinton’s

national strategy. According to Brown, the strategy continues to “redirect international efforts in

source countries” in order to provide “smarter and tougher enforcement activities in U.S. ports of

entry and at our borders” (Effectiveness of the National Drug Control Strategy and the Status of

the Drug War, 1995, p. 58). He stresses that domestic law enforcement is an integral part of

supply reduction efforts, which help achieve demand reduction goals. Furthermore, Brown tells

committee members that “...this strategy is a product of your constituents. They want policing,

they want prevention, as well as punishment. I suggest in closing...let’s do what the American

people tell us they want. Let’s do what we know will work. Let’s do what will make a

!

!

!!

32

difference” (Effectiveness of the National Drug Control Strategy and the Status of the Drug War,

1995, pg. 58). Brown’s testimony reveals a possible link between voter opinion and counterdrug

policymaking because he asserts that Clinton’s strategy, which is mainly centered on the supply

subcategory of domestic law enforcement, is a “product” of the American people that needs to

continue.

The 1996 “Drug Policy, Drug Trends” congressional record, during the 104th Congress,

offers testimony for testing Hypothesis 2. Chuck Grassley, Chairman of the Senate Caucus on

International Narcotics Control, references a 1996 poll claiming 80 percent of Americans viewed

“stopping the flow of illegal drugs to the United States as their primary foreign policy concern,”

in support of his concern that the drug issue was no longer on the Clinton administration’s

agenda (Drug Policy, Drug Trends, 1996). In addition, Grassley stresses that 94 percent of the

American public viewed drug abuse as a “crisis” or “serious problem” in the same poll (Drug

Policy, Drug Trends, 1996). With public opinion data as the backbone of his argument, Grassley

appeals to policy leaders to pay attention to voter preference. He contends, “Congress is

listening, probably because we are closer to the grassroots. We have a responsibility in the

process of representative government to keep our ear to the grassroots. I think most do” (Drug

Policy, Drug Trends, 1996). Grassley’s testimony, in contrast to Brown’s, does not support the

claim that voter preference influences anti-drug policy decisions, because he expresses concern

that policy leaders were not listening to the American people at the time. However, Grassley’s

testimony does not rule out voter preference, as his concerns were solely based on Clinton’s

administration.

!

!

!!

33

Overall, the congressional hearing testimonies detailed above show intent to influence the

decisions of policy makers with references to voter preference. However, they do not provide a

conclusive connection between public opinion and U.S. counterdrug strategy.

Hypothesis 3: U.S. supply-side policies in Latin America have been continued as a mechanism

through which to maintain regional hegemony, as well as attempting to curb the supply of illicit

drugs.

For purposes of this paper, hegemony will be defined as a leading or dominant role in

maintaining international order. In order to test Hypothesis 3, four case studies will be examined

to see if U.S. supply-side counterdrug policies serve to maintain U.S. regional hegemony, as well

as attempting to curb the supply of illicit drugs. Specific cases must be used to test this

hypothesis because hegemonic motivation is difficult to prove over the course of the multi-

decade drug war. Examining potential threats or concerns posed by particular countries to U.S.

regional hegemony will provide windows of insight into the logic behind using counterdrug

policies partly to maintain hegemonic status. The cases that will be tested are Mexico (Mérida

Initiative), Colombia (Plan Colombia), Peru (Andean Initiative), and Bolivia (Andean Initiative).

If U.S. regional hegemonic motivation is apparent at all, it is expected to be relatively

easier to distinguish in the cases of Mexico and Colombia. This expectation is based on the level

of militarization of the drug war that significantly increased with Plan Colombia, intensified after

the terrorist attacks on 9/11, and continued with the Mérida Initiative because militarization is

“an inseparable part of hegemony” (Du Boff, 2003). Peru and Bolivia are being tested to

establish whether or not maintenance of U.S. regional hegemony may also be a motivating factor

behind policies designating large amounts of counterdrug aid, void of a significantly higher level

of militarization.

!

!

!!

34

The cases of Mexico, Colombia, Peru, and Bolivia will also be examined for factors that

threaten democratic development because such factors may ultimately challenge U.S. hegemonic

power in the international system. Promoting and establishing democracy is a global U.S.

“hegemonic pursuit” (Rourke & Boyer, 2009). Theorists who support such a strong relationship

between democratic development and hegemony often refer to the “democratic peace theory,”

which posits that “democracies tend not to fight with one another but instead are generally highly

integrated, both economically and politically” (Rourke & Boyer, 2009). Therefore, supporting

and developing democratic institutions in foreign countries is considered a priority for

maintaining U.S. hegemony (Rourke & Boyer, 2009). Specifically, in Latin America,

“preserving and strengthening democracy is our primary strategic interest...Cocaine trafficking,

economic instability, and insurgencies all contribute to threaten democracy in the Andes”

(National Security Council, Interagency Working Group, 1989). Thus, the cases of Mexico,

Colombia, Peru, and Bolivia will be analyzed for the presence of illicit drug trafficking,

economic problems, and insurgent threats because these factors affect democratic development

in the country and potentially the hegemonic status of the United States.

Threats to democratic development and militarization are part of a two-prong criterion

that will be used to test Hypothesis 3 because they act as complementary factors in the case of

foreign counterdrug strategy. Militarization is primarily utilized to gain entry and influence via

the respective militaries of source and transit countries. Once established, U.S. influence is then

advanced to develop or protect democracy within these countries. Therefore, as stated

previously, each case study below will be tested for both criteria.

!

!

!!

35

Mexico

Mexico provides a relevant case study due to the high level of militarization associated

with the Mérida Initiative and presence of powerful drug cartels. Official statements regarding

the Mérida Initiative provide support that Mexican drug cartels threaten the security of Mexico,

as well as the United States. In the 2010 “Assessing the Mérida Initiative: A Report from the

Government Accountability Office (GAO)” hearing before the Committee on Foreign Affairs,

Michael T. McCaul, a subcommittee member, testifies about a discussion with former Mexican

President Calderon during a previous visit to Mexico. Calderon reportedly stated that security

was his main problem when asking for military assistance from the United States (Assessing the

Merida Initiative, 2010). McCaul elaborates,

“Since that visit, though, about 25,000 people have died in Mexico at the hands of the

drug cartels. In recent weeks, we have seen that violence escalate, the U.S. Consular

Office in Juarez being under attack, under siege; Nuevo Laredo; and this past week...a car

bomb, in a sort of Iraq-Afghanistan style, went off in Juarez, just south of the border from

El Paso, Texas, my home State. Their expanding expertise reinforces the belief that the

cartels are actively working with terrorist organizations” (Assessing the Merida Initiative,

2010).

McCaul’s testimony reveals a significant threat to U.S. security from the illicit activity and

violence of Mexican drug cartels because of their close proximity to the U.S. border and

connection with terrorist organizations. McCaul also indicates a desire for U.S. influence in

Mexico’s fight against drug cartels, by admitting his pleasure that the U.S. is able to implement a

counterdrug policy to honor Calderon’s request for military assistance (Assessing the Merida

Initiative, 2010). It appears from this testimony that the U.S. aims to advance its own security

agenda by linking the Mérida Initiative to antiterrorism goals, thus maintaining its dominant role

in the region as well as international order.

!

!

!!

36

Evidence of U.S. desire to weave the maintenance of regional influence into the Mérida

Initiative is also apparent in the 2008 “Building an Enduring Engagement in Latin America”

speech, given by Thomas A. Shannon, Jr., former Assistant Secretary of State for Western

Hemisphere Affairs. In discussing this initiative, Shannon highlights the significance of the U.S.,

Mexico, and Central American countries having a “shared security agenda” that is “directly

linked to social and economic development and the consolidation of democratic institutions”

(Shannon, 2008). He continues, “I think we have been successful in building a security

agenda…[and] can have a degree of dialogue and cooperation that will actually improve security

in the United States, but also security in Mexico and Central America and link it through

the...Counter-Drug Initiative to the entire region” (Shannon, 2008). Shannon indicates that the

counterdrug efforts of the Mérida Initiative are paramount to improving regional security, which

also contributes to securing “North America as a shared economic space” (Shannon, 2008). In

other words, the Mérida Initiative helps to protect “this $15 trillion economy” (Shannon, 2008).

By removing barriers to the commercial and trading relationships between the U.S., Mexico, and

Canada, anti-drug initiatives in Latin America are actually “armoring NAFTA,” the North

American Free Trade Agreement (Shannon, 2008). Therefore, Shannon’s speech provides

support that the counterdrug policy in Mexico partly serves to improve security in the U.S.,

Mexico, and Central America, but also to entrench America’s regional hegemonic economic

position.

Colombia

Counterdrug policy in Colombia may also partly serve to maintain hegemonic status

because it provides the initial example of significantly increased militarization as part of a U.S.

foreign anti-drug initiative. In a 1998 Senate Armed Services Committee hearing, General

!

!

!!

37

Charles Wilhelm, who was Commander of SOUTHCOM, explains the rationale behind the

initiative that was developing for Colombia at the time. Wilhelm begins his testimony by

highlighting the significance of Latin American and Caribbean regions to U.S. national interests,

mainly through trade and as oil suppliers (Twenty-first Century Security Threats, 1998). He then

comments about the Western Hemisphere’s transition to democracy. Wilhelm stresses,

“However, the roots of democracy are not deeply anchored and will require support and

role modeling to become institutionalized. These nations are struggling to counter the

threats of terrorism, international organized crime, and drug trafficking. We must remain

actively engaged in this region to deter aggression, foster peaceful conflict resolution, and

encourage democratic development while promoting stability and prosperity” (Twenty-

first Century Security Threats, 1998).

He indicates that the U.S. aimed to maintain its regional influence through Plan Colombia, not

just reduce the supply of drugs from source countries. The desire to spread U.S. influence in the

region is most evident when he refers to Latin America and the Caribbean as requiring “support

and role modeling” from active U.S. engagement to institutionalize the "roots of democracy”

(Twenty-first Century Security Threats, 1998). Wilhelm conveys U.S. concern about illicit drug

trafficking, terrorist groups, and economic interests in the region, all of which threaten

democratic development and potentially hegemony.

Wilhelm later describes Colombia as “plagued by violent insurgencies, paramilitary

forces, and drug trafficking,” with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and

the National Liberation Army (ELN) using “narcotrafficking, kidnapping and extortion to

bankroll their operations” (Twenty-first Century Security Threats, 1998). He contends that the

threats of these forces to Colombia and its bordering countries and, ultimately, U.S. national

interests requires SOUTHCOM to have “modest numbers of the right kinds of troops, with the

right skills, performing the right missions, in the right places, at the right times” (Twenty-first

Century Security Threats, 1998). Wilhelm’s testimony conveys that the U.S. deemed Colombia

!

!

!!

38

as requiring more aid than other Latin American countries at the time, due to rogue forces

threatening the institutionalization of democracy in the region. Therefore, Plan Colombia,

indeed, may have been implemented to partly maintain regional hegemony.

General James T. Hill, another former Commander of SOUTHCOM, expands on

Wilhelm’s view of Plan Colombia’s purpose in a later hearing. In the 2004 House Committee on

Government Reform hearing entitled “The War Against Drugs and Thugs,” Hill discusses his

optimistic view of the initiative’s successes, specifically in terms of ultimately achieving broader

goals than those related to narcotics. In support of continuing Plan Colombia, Hill states,

“...we must maintain our steady, patient support in order to reinforce the

successes we have seen and to guarantee a tangible return on the significant

investment our country has made to our democratic neighbor...Assisting

Colombia in their fight continues to be in our own best interest. A secure

Colombia will benefit fully from democratic processes and economic growth,

prevent narcoterrorist spillover, and serve as a regional example” (The War