Chapter 6

Work, Kinetic Energy and Potential

Energy

6.1 The Important Stuff

6.1 .1 Kinetic Energy

For an object with mass m and speed v, the kinetic energy is defined as

K =

1

2

mv

2

(6.1)

Kinetic energy is a scalar (it has magnitude but no di r ection); it is always a positive

number; and it has SI units of kg · m

2

/ s

2

. This new combination of the basic SI units is

known as the joule:

1 joule = 1 J = 1

kg·m

2

s

2

(6.2)

As we will see, the joule is also the unit of work W and potential energy U. Other energy

units often seen are:

1 erg = 1

g·cm

2

s

2

= 10

−7

J 1 eV = 1.60 × 10

−19

J

6.1 .2 Work

When an object m oves while a force is being exerted on it, then work is being done on the

obje ct by the force.

If an object moves through a displacement d while a constant force F is acting on it, the

force does an amount of work eq ual to

W = F · d = F d cos φ (6.3)

where φ is the angle between d and F.

Work is also a scalar and has units of 1 N · m. But we can see that this is the same as

the joule, defined in Eq. 6.2.

127

128 CHAPTER 6. WORK, KINETIC ENERGY AND POTENTIAL ENERGY

Work can be negative; this happens when the angle between force and displacement is

larger than 90

◦

. It can also be zero; this happens if φ = 90

◦

. To do work, the force must

have a component along (or opposite to) the direction of the motion.

If several different (constant) forces act on a mass while it moves though a displacement

d, then we can talk about the net work done by the forces,

W

net

= F

1

· d + F

1

· d + F

1

· d + . . . (6.4)

=

X

F

· d (6.5)

= F

net

· d (6.6)

If the force which acts on the objec t is not constant while the object moves then we must

perform an integral (a sum) to find the work done.

Suppose the object moves along a straight line (say, along the x axis, from x

i

to x

f

) while

a force whose x component is F

x

(x) acts on it. (That is, we know the force F

x

as a function

of x.) Then the work done is

W =

Z

x

f

x

i

F

x

(x) dx (6.7)

Finally, we can give the most general expression for the work done by a force. If an object

moves from r

i

= x

i

i + y

i

j + z

i

k to r

f

= x

f

i + y

f

j + z

f

k while a force F(r) acts on it the work

done is:

W =

Z

x

f

x

i

F

x

(r) dx +

Z

y

f

y

i

F

y

(r) dy +

Z

z

f

z

i

F

z

(r) dz (6.8)

where the integrals are calcul ated along the path of the object’s motion. This expression

can be abbreviated as

W =

Z

r

f

r

i

F · dr . (6.9)

This is rather abstract! But most of the problems where we need to calculate the work done

by a force will just involve Eqs. 6.3 or 6.7

We’re familiar with the force of gravity; gravity does work on objects which move ver-

tically. One can show that if the height of an object has changed by an amount ∆y then

gravity has done an amount of work eq ual to

W

grav

= −mg∆y (6.10)

regardless of the horiz ontal displ acement. Note the minus sign here; if the object increases

in height i t has moved o ppositely to the force of gravity.

6.1 .3 Spring Force

The most famous example of a force whose value depends on position is t he spring force,

which descr ibes the force ex erted on an object by the end of an ideal spring. An ideal

spring will pull inward on the object attached to its end with a force proportional to the

amount by which i t is stretched; it will push outward on the obj ect attached to its with a

force proportional to amount by which it i s compressed.

6.1. THE IM PORTAN T STUFF 129

If we describe the motion of the end of the spring with the coordinate x and put the

origin of the x axis at the place where the spring exerts no force (the equilibrium positi on)

then the spring f orce is given by

F

x

= −kx (6.11)

Here k is force constant, a number which is different f or e ach ideal spring and is a measure

of its “stiffness”. It has units of N/ m = kg/ s

2

. This e quation is usually referred to as

Hooke’s law. It gives a decent description of the behavior of real springs, just as long as

they can oscillate about t heir equilibrium positions and they are not stretched by too much!

When we calculate the work done by a spring on the object attached to its end as the

obje ct moves from x

i

to x

f

we get:

W

spring

=

1

2

kx

2

i

−

1

2

kx

2

f

(6.12)

6.1 .4 The Work–Kinetic Energy Theorem

One can show that as a particle moves from point r

i

to r

f

, the change in kinetic energy of

the object is equal to the net work done on it:

∆K = K

f

− K

i

= W

net

(6.13)

6.1 .5 Power

In certai n applications we are interested in the rate at which work is done by a force. If an

amount of work W is done in a time ∆t , then we say that the average power P due to the

force is

P =

W

∆t

(6.14)

In the limit in which both W and ∆t are very small the n we have the instantaneous power

P , written as:

P =

dW

dt

(6.15)

The unit of power is the watt, defined by:

1 watt = 1 W = 1

J

s

= 1

kg·m

2

s

3

(6.16)

The watt is related to a quaint old unit of power called the horsepower:

1 horsepower = 1 hp = 550

ft·lb

s

= 746 W

One can show that if a force F acts on a particle moving with velocity v then the

instantaneous rate at which work is being done on the particle is

P = F · v = F v cos φ (6.17)

where φ is the angle between the directions of F and v.

130 CHAPTER 6. WORK, KINETIC ENERGY AND POTENTIAL ENERGY

6.1 .6 Conservative Forces

The work done on an object by the force of gravity does not depend on the path taken to

get from one position to another. The same is true for the spring f orce. In both cases we

just need to know the i nitial and final coordinates to be able to find W , the work done by

that force.

This situation also occurs with the general l aw for the force of gravity (Eq. 5.4.) as well

as with the electric al force which we learn about in the second semester!

This is a different situation from the friction forces studied in Chapter 5. Friction forces

do work on moving masses, but to figure out how much work, we need to know how the

mass got from one place to another.

If the net work done by a force does not depend on the path taken between two points,

we say that the f orce is a conservative force. For such forces it is al so true that the net

work done on a particle moving on around any closed path is zero.

6.1 .7 Potential Energy

For a conservative force it is possible to find a function of position called the potenti al

energy, which we will write as U(r), from which we can find the work done by the force.

Suppose a particle moves from r

i

to r

f

. Then the work done on the particl e by a conser-

vative force is related to the corresponding potential energy function by:

W

r

i

→r

f

= −∆U = U(r

i

) − U(r

f

) (6.18)

The potential energy U(r) also has units of joules in the SI system.

When our physics problems involve forces for which we can have a potential energy

function, we usually think about the change in potential energy of the objects rather than the

work done by these forces. However for non–conservative forces, we must directly c al culate

their work (or else deduce it from the data given in our problems).

We have encountered two conservative forces so far in our study. The simplest is the

force of gravity near the surface of the earth, namely −mgj for a mass m, where the y axis

points upward. For this force we can show that the potential energy function is

U

grav

= mgy (6.19)

In using this eq uation, it is arbitrary where we put the origin of the y axis (i.e. what we call

“zero height”). But once we make the choice for the origin we must s tick with it.

The other conservative force i s the spring force. A spring of force constant k which is

extende d f r om its equilibrium position by an amount x has a potential energy given by

U

spring

=

1

2

kx

2

(6.20)

6.1. THE IM PORTAN T STUFF 131

6.1 .8 Conservation of Mechanical Energy

If we separate the forces in the world into c onservative and non-conservative forces, then the

work–kinetic energy theorem says

W = W

con s

+ W

non−con s

= ∆K

But from Eq. 6.18, the work done by conservative forces can be written as a change in

potential energy as:

W

con s

= −∆U

where U is the sum of all types of potential energy. With this replacement, we find:

−∆U + W

non−con s

= ∆K

Rearranging this gives t he general theorem of the Conservation of Mechanical Energy:

∆K + ∆U = W

non−con s

(6.21)

We define the t otal energy E of the system as the sum of the kinetic and potential

energies of all the objects:

E = K + U (6.22)

Then Eq. 6.21 can be written

∆E = ∆K + ∆U = W

non−con s

(6.23)

In words, thi s equation says that the total mechanical energy changes by the amount of work

done by the non–conservative forces.

Many of our physics problems are about situations where all the forces acting on the

moving objects are conservative; loosely speaking, this means that there is no fri ction, or

else there is negligible friction.

If so, then the work done by non–conservative forces is ze r o, and Eq. 6.23 takes on a

simpler form:

∆E = ∆K + ∆U = 0 (6.24)

We can write this equation as:

K

i

+ U

i

= K

f

+ U

f

or E

i

= E

f

In other words, for those cases where we can ignore friction–type forces, if we add up all

the kinds of energy for the particle’s initial position, it is equal to the sum of all the kinds

of energy for the particle’s final position. In such a case, the amount of mechanical energy

stays the same. . . it i s c onserved.

Energy conservation is useful in problems where we only need to know about positions

or speeds but not time for the motion.

132 CHAPTER 6. WORK, KINETIC ENERGY AND POTENTIAL ENERGY

6.1 .9 Work Done by N on–Conservative Forces

When the system does have friction forces then we must go back to Eq. 6.23. The change in

total m echanical energy equals the work done by the non–conservative forces:

∆E = E

f

− E

i

= W

non−con s

(In the c ase of sliding friction with the rule f

k

= µ

k

N it is possible to compute the work

done by the non–conservative force.)

6.1 .10 Relationship Between Conse rvative Forces and Potential

Energy (Optional?)

Eqs. 6.9 (the general expression for work W ) and 6.18 give us a relation between the force F

on a particl e (as a function of position, r) and t he change in potential energy as the particle

moves from r

i

to r

f

:

Z

r

f

r

i

F · dr = −∆U (6.25)

Ve ry loosely speaking, potential energy is the (negative) of the integral of F(r). Eq. 6.25

can be rewritten to show that (loosely speaking!) the force F(r) is the (m inus) derivative of

U(r). More precisely, the components of F can be gotten by taking pa rtial derivatives of U

with respect t o the Cartesian coordinates:

F

x

= −

∂U

∂x

F

y

= −

∂U

∂y

F

z

= −

∂U

∂z

(6.26)

In case you haven’t come across partial derivatives i n your mathematics education yet:

They come up when we have functions of several variables (like a function of x, y and z); if

we are taking a partial derivati ve with respect to x, we treat y and z as constants.

As you may have al r eady learned, the three parts of Eq. 6.26 can be compactly writte n

as

F = −∇U

which can be expressed in words as “F is the negative gradient of U”.

6.1 .11 Other Kinds of Energy

This chapter covers the mechanical energy of particles; later, we consider extende d objects

which can rotate, and they will also have rotational kinetic energy. Real objects also have

temperature so that they have thermal energy. When we take into account all types of

energy we find that total energy is completely conserved. . . we never lose any! But here we

are counting only the mechanical energy and if (in real objects!) fric tion is present some of

it can be lost to become thermal energy.

6.2. WORKED EXAMPLES 133

6.2 Worked Examples

6.2 .1 Kinetic Energy

1. If a Saturn V rocket with an Apollo spacecraft attached has a combined mass

of 2.9 × 10

5

kg and is to reach a spe ed of 11.2

km

s

, how much kinetic energy will it

then have? [HRW5 7-1]

(Convert some units first.) The speed of the ro cket will be

v = (11.2

km

s

)

10

3

m

1 km

!

= 1.12 × 10

4

m

s

.

We know its mass: m = 2.9 × 10

5

kg. Using the definition of kinetic energy, we have

K =

1

2

mv

2

=

1

2

(2.9 × 10

5

kg)(1.12 × 10

4

m

s

)

2

= 1.8 × 10

13

J

The rocket will have 1.8 × 10

13

J of kinetic energy.

2. If an electron (mass m = 9.11 × 10

−31

kg) in copper near the lowest possible

temperature has a kinetic energy of 6.7×10

−19

J, what is t he speed of the electron?

[HRW5 7-2]

Use t he definition of kinetic energy, K =

1

2

mv

2

and the given values of K and m, and

solve for v. We find:

v

2

=

2K

m

=

2(6.7 × 10

−19

J)

(9.11 × 10

−31

kg)

= 1.47 × 10

12

m

2

s

2

which gives:

v = 1.21 × 10

6

m

s

The speed of the electron is 1.21 × 10

6

m

s

.

6.2 .2 Work

3. A floating i ce block is pushed through a displacem ent of d = (15 m)i − (12 m)j

along a straight embankment by rushing water, which exerts a force F = (210 N)i−

(150 N)j on the block. How much work does the force do on the block during the

displacem ent? [HRW5 7-11]

Here we have the simple case of a straight–line displaceme nt d and a constant force F.

Then the work done by the force is W = F · d. We are given all the components, so we can

compute the dot product using the components of F and d:

W = F · d = F

x

d

x

+ F

y

d

y

= (210 N)((15 m) + (−150 N)(−12 m) = 4950 J

134 CHAPTER 6. WORK, KINETIC ENERGY AND POTENTIAL ENERGY

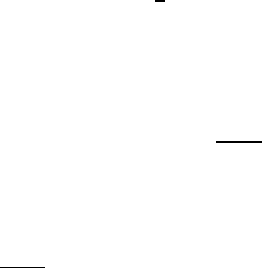

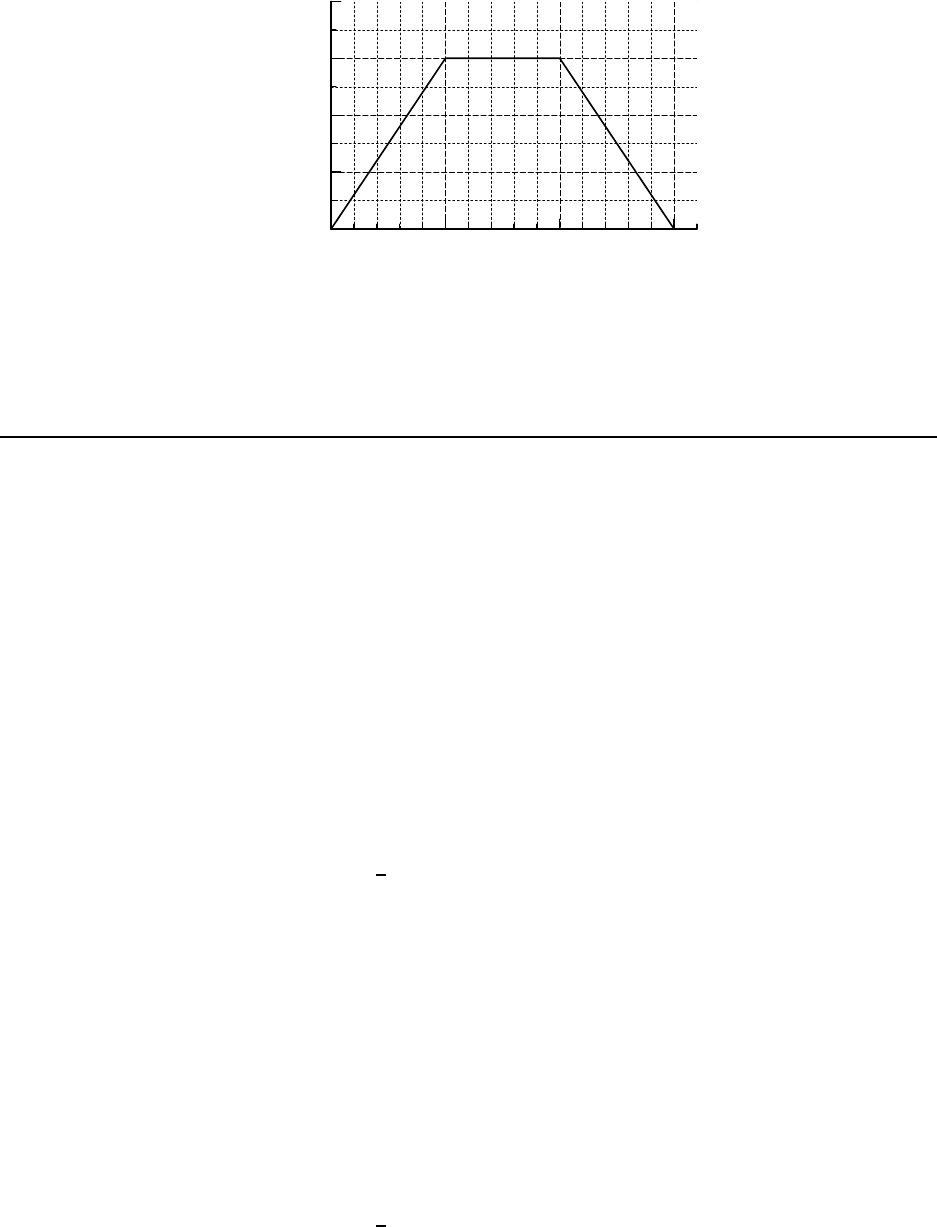

0.0 5.0 10.0 15.0

x, m

0.00

1.00

2.00

3.00

4.00

F

x

, N

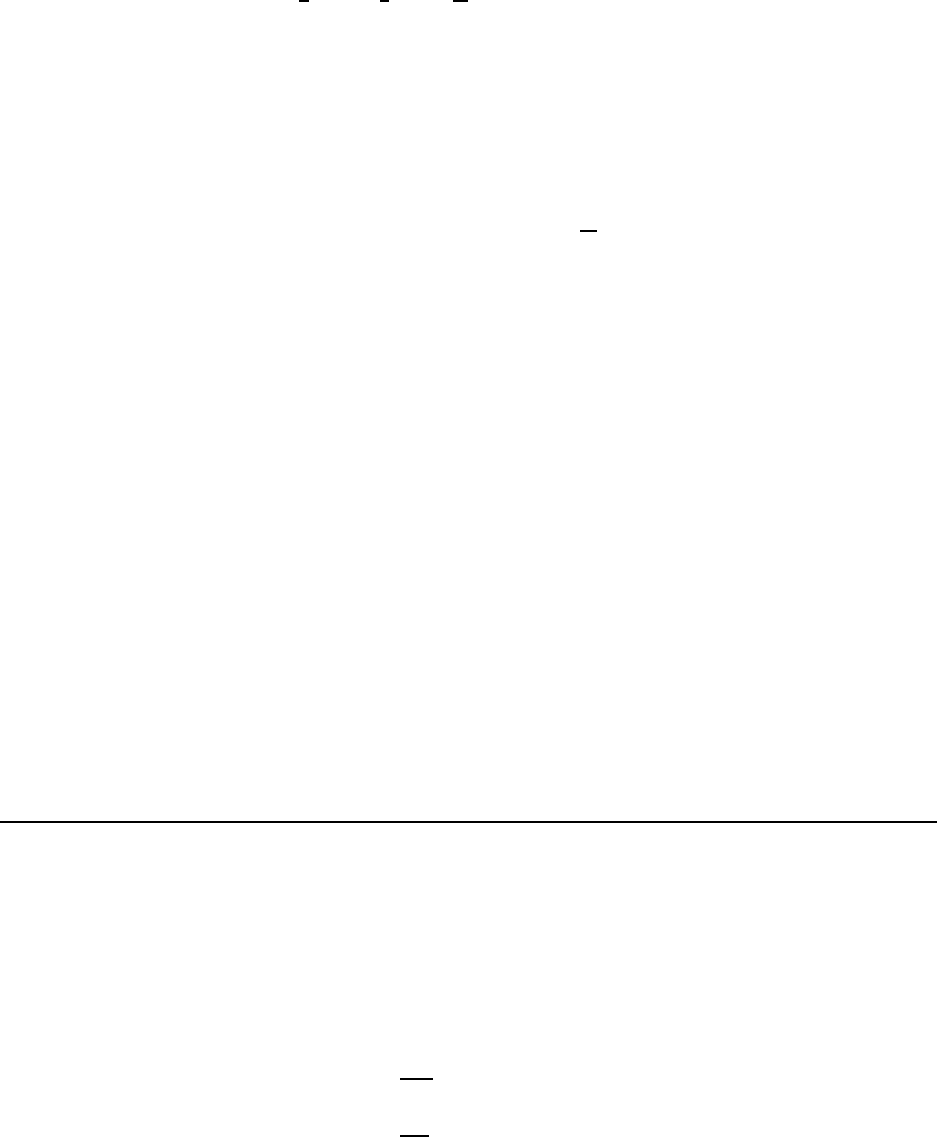

Figure 6.1: Force F

x

, which depends on po sition x; see Example 4.

The force does 4950 J of work.

4. A particle is subject to a force F

x

that varies with position as in Fig. 6.1. Find

the work done by the force on the body as it moves (a) from x = 0 to x = 5.0 m,

(b) from x = 5.0 m to x = 10 m and (c) from x = 10 m to x = 15 m. (d) What is the

total work done by the force over the distance x = 0 to x = 15 m? [Ser4 7-23]

(a) Here the force is not the same all through the object’s motion, so we can’t use the

simple formula W = F

x

x. We must use the more general expression f or the work done when

a particle moves along a straight line,

W =

Z

x

f

x

i

F

x

dx .

Of course, this i s just the “area under the curve” of F

x

vs. x from x

i

to x

f

.

In part (a) we want thi s “area” evaluated from x = 0 to x = 5.0 m. From the figure, we

see that this is just half of a rectangle of base 5.0 m and height 3.0 N. So the work done is

W =

1

2

(3.0 N)(5.0 m) = 7.5 J .

(Of course, when we evaluate the “area”, we just keep the units which go along with the

base and the height; here they were mete rs and newtons, the product of which is a joule.)

So the work done by the force for this displacem ent is 7.5 J.

(b) The region under the curve from x = 5.0 m to x = 10.0 m is a full rect angle of base

5.0 m and hei ght 3.0 N . The work done for this movement of the particl e is

W = (3.0 N)( 5.0 m) = 15. J

(c) For the movement from x = 10.0 m to x = 15.0 m the region under the curve is a half

rectangle of base 5.0 m and height 3.0 N. The work done is

W =

1

2

(3.0 N)(5.0 m) = 7.5 J .

6.2. WORKED EXAMPLES 135

(d) The total work done over the distance x = 0 to x = 15.0 m is the sum of the three

separate “areas”,

W

total

= 7.5 J + 15. J + 7.5 J = 30. J

5. What wor k is done by a force F = (2x N)i + (3 N )j, with x in meters, that moves

a particle from a position r

i

= ( 2 m)i + (3 m)j to a position r

f

= −(4 m)i − (3 m)j ?

[HRW5 7-31]

We use the general definition of work (for a two–dimensional problem),

W =

Z

x

f

x

i

F

x

(r) dx +

Z

y

f

y

i

F

y

(r) dy

With F

x

= 2x and F

y

= 3 [we mean that F in newtons when x is in meters; work W will

come out with units of joules!], we find:

W =

Z

−4 m

2 m

2x dx +

Z

−3 m

3 m

3 dy

= x

2

−4 m

2 m

+ 3x

−3 m

3 m

= [(16) − (4)] J + [(−9) − (9)] J

= −6 J

6.2 .3 Spring Force

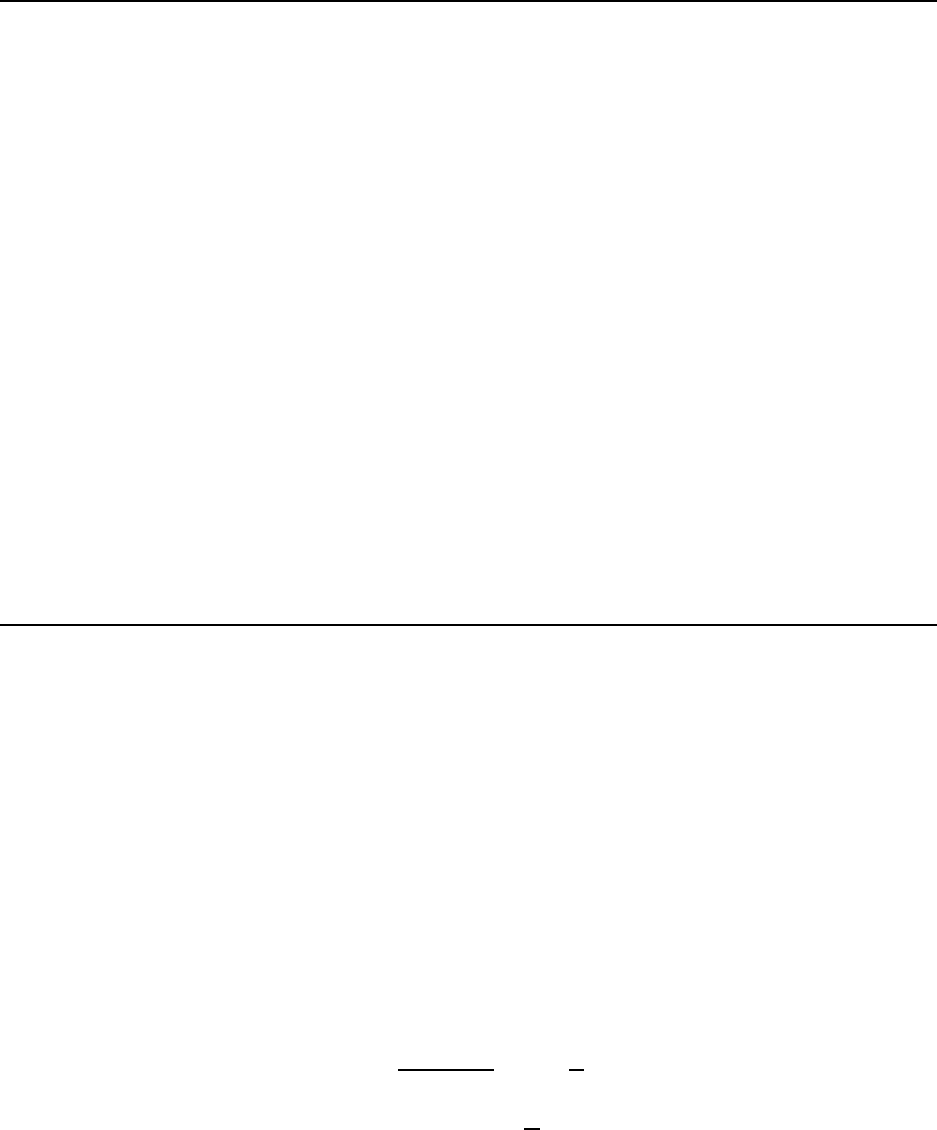

6. An archer pul ls her bow string back 0.400 m by exerting a force t hat increases

from zero to 230 N. (a) What i s the equivalent spring constant of the bow? (b)

How much work is done i n pulling the bow? [Ser4 7-25]

(a) While a bow string is not literally spring, it may behave like one in that it exerts a force

on t he thing attached to it (like a hand!) that is proportional to the distance of pull from

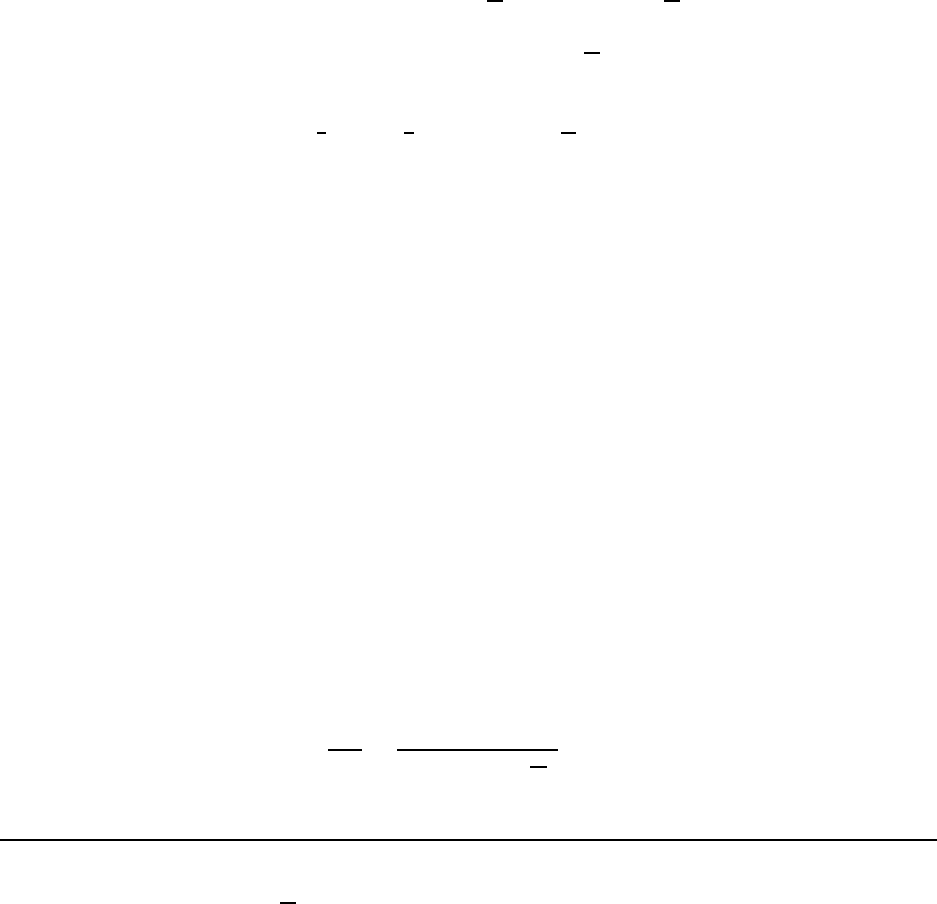

the equilibrium position. The correspondence is illustrated in F ig. 6.2.

We are told that when the string has been pulled back by 0.400 m, the string exerts a

restoring force of 230 N. The magnitude of the string’s force is equal to the force constant k

times the magnitude of the displacement; this gives us:

|F

string

| = 230 N = k(0.400 m)

Solving for k,

k =

(230 N)

(0.400 m)

= 575

N

m

The (equivalent) spring constant of the bow is 575

N

m

.

136 CHAPTER 6. WORK, KINETIC ENERGY AND POTENTIAL ENERGY

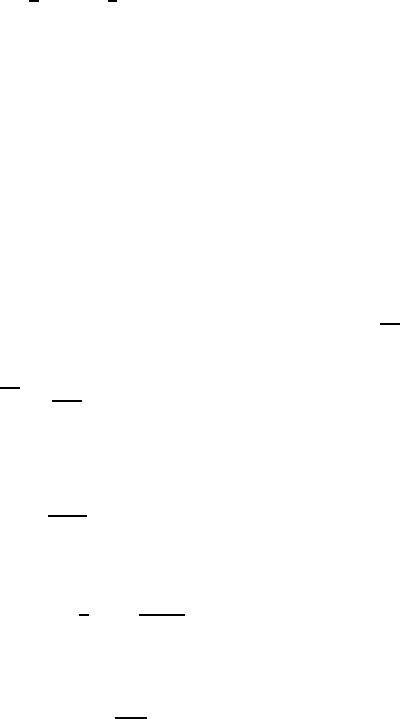

x

F

x=0

x=0

F

(a)

(b)

x

Figure 6.2: The force of a bow string (a) on the object pulling it ba ck can be modelled as as ideal spring

(b) exerting a restoring force on the mass attached to its end.

(b) Still treating the bow string as if it were an ideal spring, we note that in pulling the

string from a displacement of x = 0 to x = 0.400 m the string does as amount of work on

the hand given by Eq. 6.12:

W

string

=

1

2

kx

2

i

−

1

2

kx

2

f

= 0 −

1

2

(575

N

m

)(0.400 m)

2

= −46.0 J

Is thi s answer to the question? Not quite. . . we were reall y asked for the work done by the

hand on the bow string. But at all times during the pulling, the hand exerted an equal and

opposite f orce on the string. The force had the opposite direc t ion, so the work that it did

has the opposite sign. The work done (by the hand) in pul ling the bow is +46.0 J.

6.2 .4 The Work–Kinetic Energy Theorem

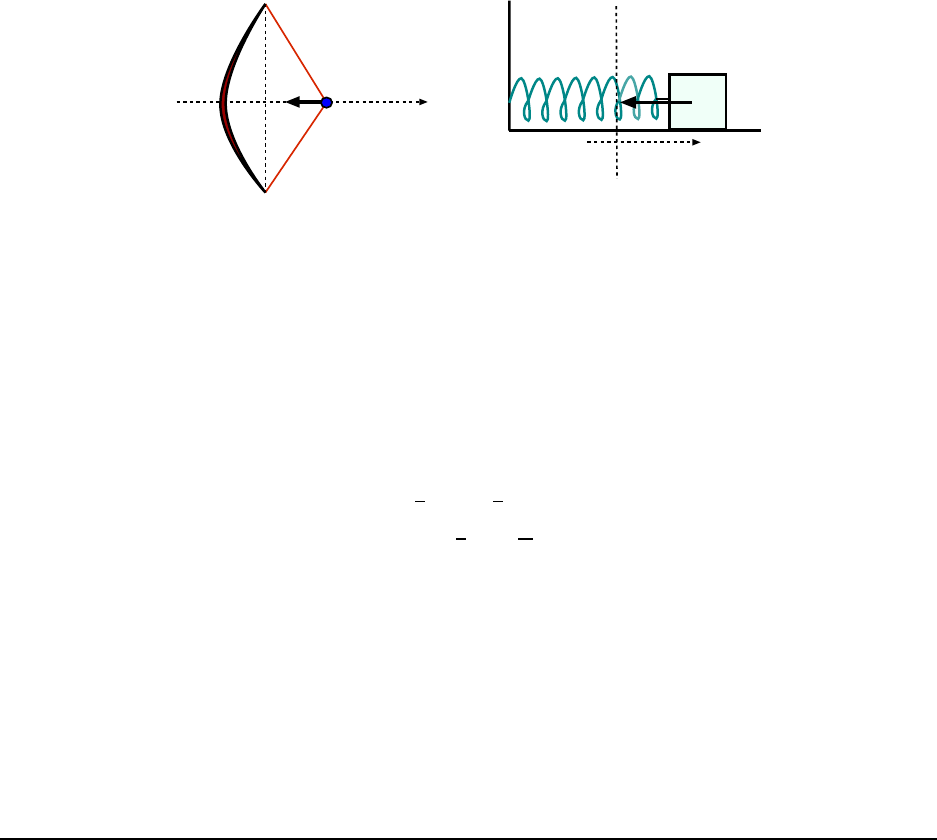

7. A 40 kg box initially at r est is pushed 5.0 m along a rough hori zontal floor with

a constant appli ed horizontal force of 130 N. If the coefficient of friction between

the box and floor is 0.30, find (a) the work done by the applied force, (b) the

energy lost due to friction, (c) the change in kinetic energy of the box, and (d)

the final speed of the box. [Ser4 7-37]

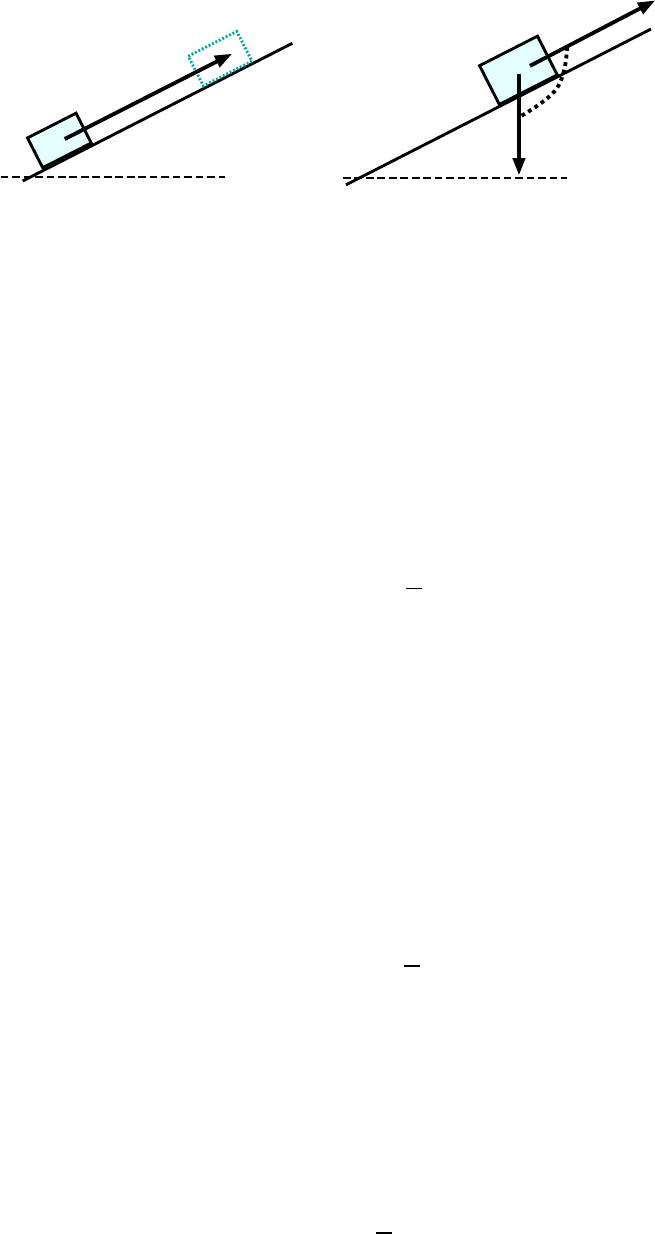

(a) The motion of the box and the forces which do work on it are shown in Fig. 6.3(a). The

(constant) applied force points in the same direction as the displacement. Our formula for

the work done by a constant force gives

W

app

= F d cos φ = (130 N)(5.0 m) cos 0

◦

= 6.5 × 10

2

J

The applied force does 6.5 × 10

2

J of work.

(b) Fig. 6.3(b) shows all the forces acting on the box.

6.2. WORKED EXAMPLES 137

f

fric

F

app

d

F

app

f

fric

mg

N

(a)

(b)

Figure 6.3: (a) Applied force and friction fo rce both do work on the box. (b) D iagram showing all the

forces acting on the box.

The vertical forces acting on the b ox are gravity (mg, downward) and the floor’s normal

force (N, upward). It follows that N = mg and so the magnitude of the friction force is

f

fric

= µN = µmg = (0.30)(40 kg)(9.80

m

s

2

) = 1.2 × 10

2

N

The friction force is directed opposite the direction of motion (φ = 180

◦

) and so t he work

that it does is

W

fric

= F d cos φ

= f

fric

d cos 180

◦

= (1.2 × 10

2

N)(5.0 m)(−1) = −5. 9 × 10

2

J

or we might say that 5.9 × 10

2

J is lost to friction.

(c) Since the normal force and gravity do no work on the box as it moves, the net work done

is

W

net

= W

app

+ W

fric

= 6.5 × 10

2

J − 5.9 × 10

2

J = 62 J .

By the work–Kinetic Energy Theorem, thi s is equal to the change in kinetic energy of the

box:

∆K = K

f

− K

i

= W

net

= 62 J .

(d) He r e, the initial kinetic energy K

i

was zero because the box was initially at rest. So we

have K

f

= 62 J. From the definition of kinetic energy, K =

1

2

mv

2

, we get the final speed of

the box:

v

2

f

=

2K

f

m

=

2(62 J)

(40 kg)

= 3.1

m

2

s

2

so that

v

f

= 1.8

m

s

8. A crate of mass 10.0 kg is pulled up a r ough incli ne with an initial speed of

1.50

m

s

. The pulling force is 100 N parallel to the i ncline, which makes an angle of

20.0

◦

with the horizontal. The coeffi cient of kinetic friction is 0.400, and the crate

138 CHAPTER 6. WORK, KINETIC ENERGY AND POTENTIAL ENERGY

20

o

5.00 m

F

d

70

o

(a)

(b)

f = 110

o

20

o

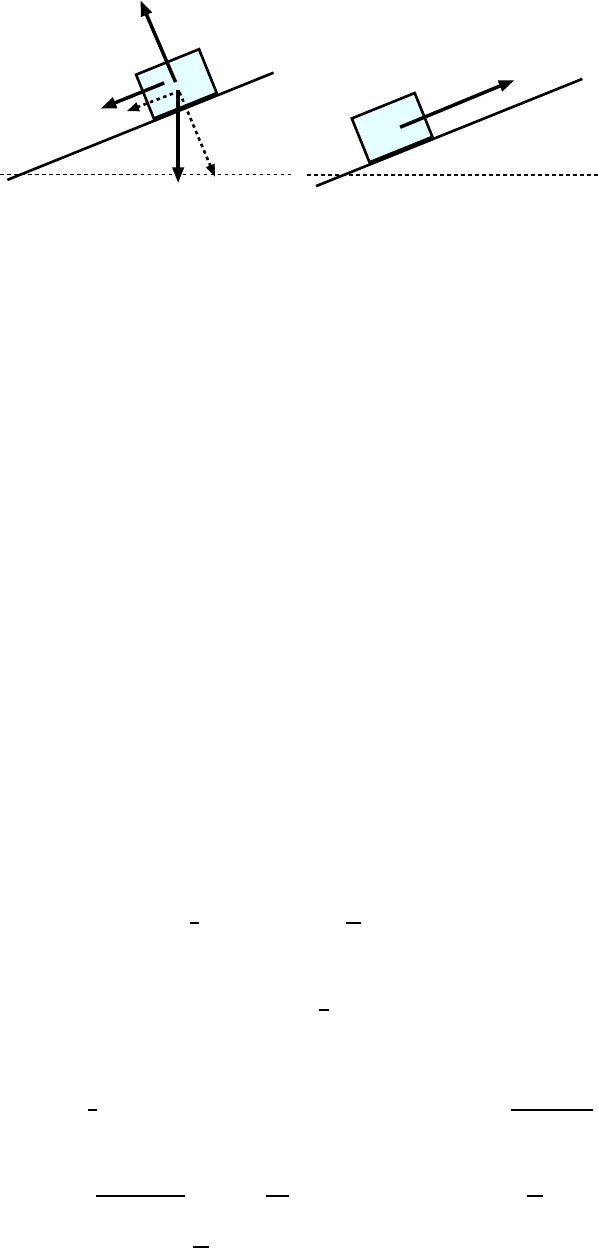

Figure 6. 4: (a) Block moves 5.00 m up plane while acted upon by gravity, f riction and an applied force.

(b) Directions of the displacement and the force of gravity.

is pulled 5.00 m. (a) How much work is done by gravity? (b) How much ene rgy

is lost due to friction? (c) How much work i s done by the 100 N force? (d) What

is the change in kinetic energy of the crate? (e) What is the speed of the cr ate

after being pulled 5.00 m? [Ser4 7-47]

(a) We can calc ulate the work done by gravity in two ways. First, we can use the definition:

W = F · d. The magnitude of the gravity force i s

F

grav

= mg = (10.0 kg(9.80

m

s

2

) = 98.0 N

and the displacement has magnitude 5.00 m. We see from geometry (see Fig. 6.4(b)) that the

angle between the force and displacement vectors is 110

◦

. Then the work done by gravity is

W

grav

= F d cos φ = (98.0 N)(5.00 m) cos 110

◦

= −168 J .

Another way to work the problem is to plug the right value s into Eq. 6.10. From simple

geometry we see that the change in height of the crate was

∆y = (5.00 m) sin 20

◦

= +1.71 m

Then the work done by gravity was

W

grav

= −mg∆y = −(10.0 kg)(9.80

m

s

2

)(1.71 m) = −168 J

(b) To find the work done by friction, we need to know the force of friction. The forces

on the blo ck are shown i n Fig. 6.5(a). As we have seen before, the normal force b etween

the slope and the block is mg cos θ (with θ = 20

◦

) so as to cancel the normal component of

the force of gravity. Then the force of kinetic friction on the block points down the slope

(opposite the motion) and has magnitude

f

k

= µ

k

N = µmg cos θ

= (0.400)(10.0 kg)(9.80

m

s

2

) cos 20

◦

= 36.8 N

6.2. WORKED EXAMPLES 139

q = 20

o

mg

mg cos q

N

f

k

20

o

F

appl

(a)

(b)

Figure 6.5: (a) Gravity and friction forces which a ct on the block. (b) The applied force of 100 N is along

the direction of the motion.

This f orce points exactly opposite the direction of the displacement d, so the work done by

friction is

W

fric

= f

k

d cos 180

◦

= (36.8 N)(5.00 m)(−1) = −184 J

(c) The 100 N applied force pulls in the direction up the slope, which is along the di rection

of the displacement d. So the work that is does is

W

appl

= F d cos 0

◦

= (100 N)(5.00 m)(1) = 500. J

(d) We have now found the work done by each of the f orces acting on the crate as it m oved:

Gravity, friction and the applied force. (We should note the the normal force of the surface

also acte d on the crate, but being perpendicular to the motion, it did no work.) The net

work done was:

W

net

= W

grav

+ W

fric

+ W

appl

= −168 J − 184 J + 500. J = 148 J

From the work–energy the orem, this is e qual to the change in kinetic e nergy of the box:

∆K = W

net

= 148 J.

(e) The initial kinetic energy of the crate was

K

i

=

1

2

(10.0 kg)(1.50

m

s

)

2

= 11.2 J

If the final speed of the c r ate is v, then the change in kinetic e nergy was:

∆K = K

f

− K

i

=

1

2

mv

2

− 11.2 J .

Using our answer from part (d), we get:

∆K =

1

2

mv

2

− 11.2 J = 148 J =⇒ v

2

=

2(159 J)

m

So then:

v

2

=

2(159 J)

(10.0 kg)

= 31.8

m

2

s

2

=⇒ v = 5.64

m

s

.

The final speed of the crate is 5.64

m

s

.

140 CHAPTER 6. WORK, KINETIC ENERGY AND POTENTIAL ENERGY

W= 700 N

10.0 m

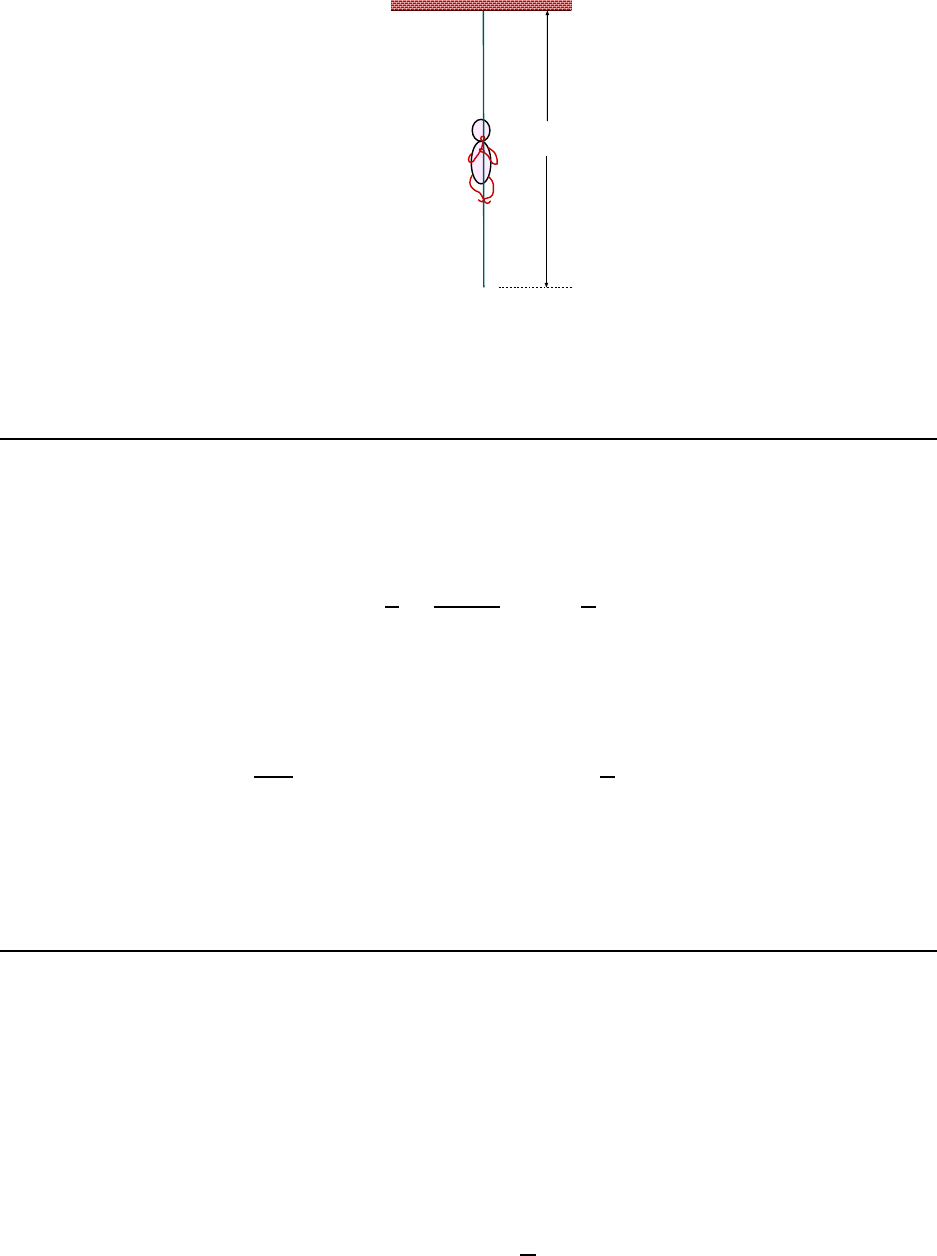

Figure 6.6: Marine climbs rope in Example 9. You don’t like my drawing? Tell it to the Marines!

6.2 .5 Power

9. A 700 N marine in basic training climbs a 10.0 m vertical rope at a constant

speed of 8.00 s. What is his power output? [Ser4 7-53]

Marine i s shown in Fig. 6.6. The speed of the marine up the rope i s

v =

d

t

=

10.0 m

8.00 s

= 1.25

m

s

The forces acting on the marine are gravity (700 N, downward) and the force of the rope

which must be 700 N upward since he moves at constant velocity. Since he moves in the

same direc tion as the rope’s force, the rope does work on the marine at a rate equal to

P =

dW

dt

= F · v = F v = (700 N)(1.25

m

s

) = 875 W .

(It may be hard to think of a stationary rope doing work on anybody, but that is what is

happening here.)

This number represents a rate of change in the potential energy of the marine; the energy

comes from someplace . He is losing (chemical) e nergy at a rate of 875 W.

10. Water flows over a section of Niagara Falls at a rate of 1.2 × 10

6

kg/ s and falls

50 m. How many 60 W bulbs can be lit with this power? [Ser4 7-54]

Whoa! Waterfalls? Bulbs? What’s going on here??

If a certai n mass m of water d rops by a height h (that is, ∆y = −h), then from Eq. 6.10,

gravity does an amount of work equal to m gh. If this change in height occurs over a time

interval ∆t then the rate at which gravity does work is mgh/∆t.

For Niagara Falls, if we consider the amount of water that falls in one second, then a

mass m = 1.2 × 10

6

kg falls through 50 m and the work done by gravity is

W

grav

= mgh = (1.2 × 10

6

kg)(9.80

m

s

2

)(50 m) = 5.88 × 10

8

J .

6.2. WORKED EXAMPLES 141

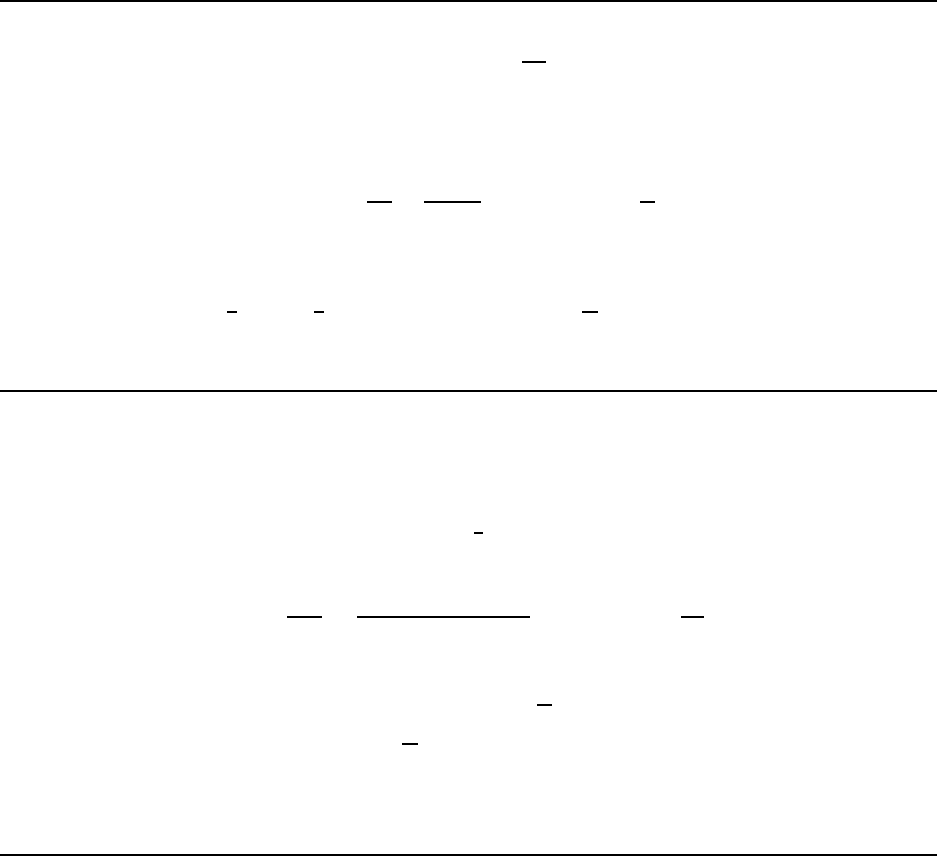

v

0= 20

m/s

v

34

o

v

y

=0

(Max height)

h

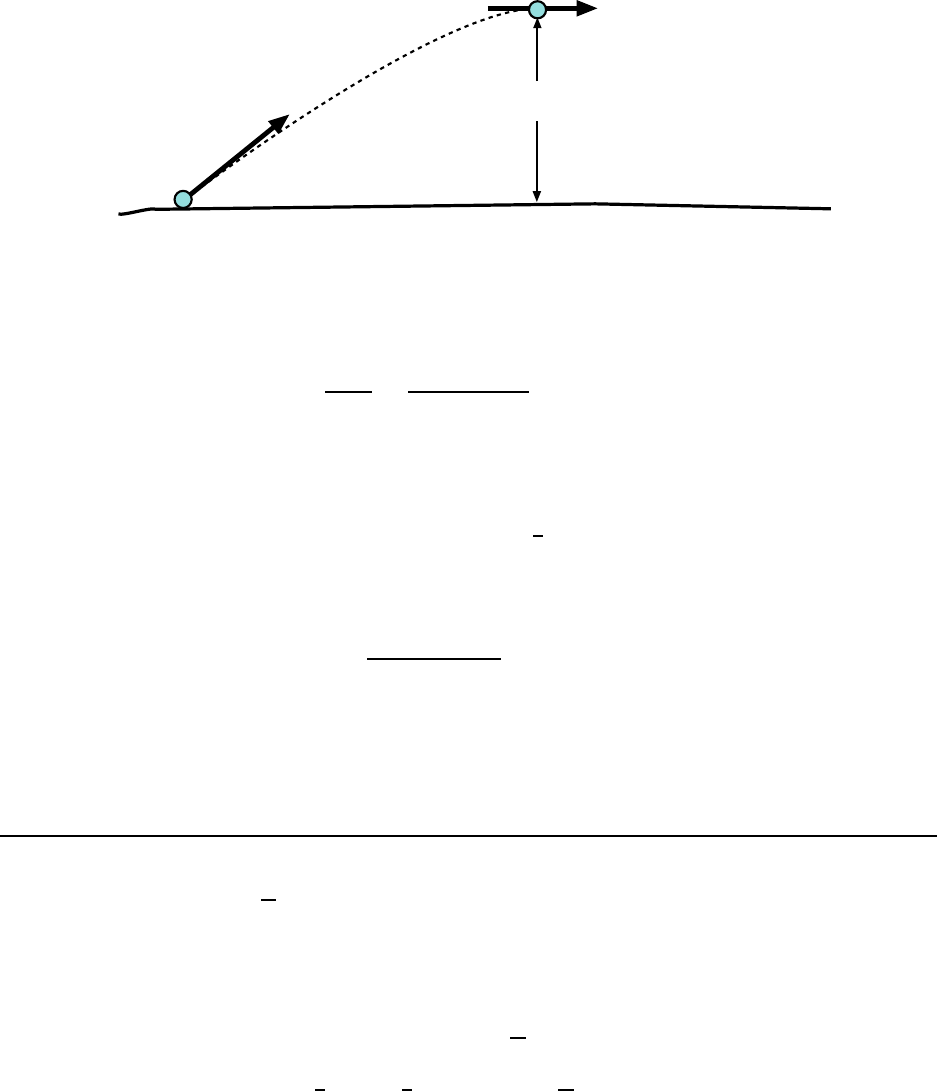

Figure 6.7: Snowball is l aunched at angle of 34

◦

in Example 11.

This occurs every second, so gravity does work at a rate of

P

grav

=

mgh

∆t

=

5.88 × 10

8

J

1 s

= 5.88 × 10

8

W

As we se e later, this is also the rate at which the water loses potential energy. This energy

can be converted t o other forms, such as the e lectric al energy to make a light bul b f unction.

In this highly idealistic example, all of the energy i s c onverted to electrical e nergy.

A 60 W light bulb uses ene r gy at a rate of 60

J

s

= 60 W. We see that Niagara Falls

puts out energy at a rate much bigger than this! Assuming all of it goes to the bul bs, then

divi ding the total energy consumption rate by the rate for one bulb tells us that

N =

5.88 × 10

8

W

60 W

= 9.8 × 10

6

bulbs can be lit.

6.2 .6 Conservation of Mechanical Energy

11. A 1.50 kg snowball is shot upward at an angle of 34.0

◦

to the horizontal with

an initial speed of 20.0

m

s

. (a) What is its initial kinetic ene rgy? (b) By how much

does the gravitati onal pote ntial energy of the snowball–Earth system change as

the snowball moves from the launch point to the point of maximum height? (c)

What is that maximum height? [HRW5 8-31]

(a) Since the initial speed of the snowball is 20.0

m

s

, we have its initial kinetic energy:

K

i

=

1

2

mv

2

0

=

1

2

(1.50 kg)(20.0

m

s

)

2

= 300. J

(b) We need to remember that since this projectile was not fired straight up, it will still

have some kinetic ene r gy when it gets to maximum height ! That means we have to think a

little harder before applying energy principles to answer this question.

142 CHAPTER 6. WORK, KINETIC ENERGY AND POTENTIAL ENERGY

At maximum height, we know that the y component of the snowball’s velocity i s zero.

The x component is not zero.

But we do know that since a projectile has no horiz ontal acceleration, the x component

will remain constant; it will keep its initial value of

v

0x

= v

0

cos θ

0

= (20.0

m

s

) cos 34

◦

= 16.6

m

s

so the speed of the snowball at maximum height is 16.6

m

s

. At maximum height, (the final

position) the kinetic energy is

K

f

=

1

2

mv

2

f

=

1

2

(1.50 kg)(16.6

m

s

)

2

= 206. J

In this problem there are only conservative forces (namely, gravity). The mechanical

energy is conserved:

K

i

+ U

i

= K

f

+ U

f

We already f ound the initial kinetic energy of the snowball: K

i

= 300. J. Using U

grav

= mgy

(with y = 0 at ground level), the initial potential energy is U

i

= 0. Then we can find the

final potential ener gy of the snowball:

U

f

= K

i

+ U

i

− K

f

= 300. J + 0 − 206. J

= 94. J

The final gravitational potential e nergy of the snowball–earth system (a long–winded way

of saying what U is!) is then 94. J. (Since its original value was zero, this is the answer to

part (b).)

(c) If we call the maximum height of the snowball h, then we have

U

f

= mgh

Solve for h:

h =

U

f

mg

=

(94. J)

(1.5 kg)(9.80

m

s

2

)

= 6.38 m

The maximum height of the snowball is 6.38 m.

12. A pendulum consists of a 2.0 kg stone on a 4.0 m string of negligible mass. The

stone has a speed of 8.0

m

s

when it passes its lowest point. (a) What is the speed

when the string is at 60

◦

to the vertical? (b) What i s the greatest angle with the

vertical that the string will reach during the stone’s motion? (c) If the potential

energy of the pendulum–Earth system is taken to be zero at the stone’s l owest

point, what is the total mechanical e nergy of the system? [HRW5 8-32]

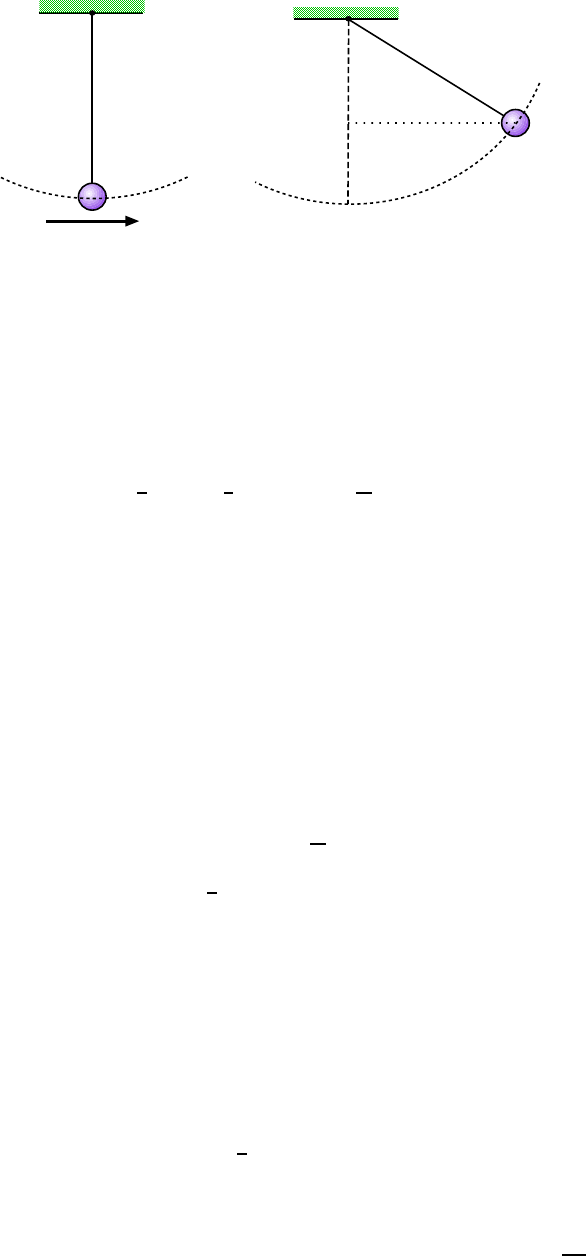

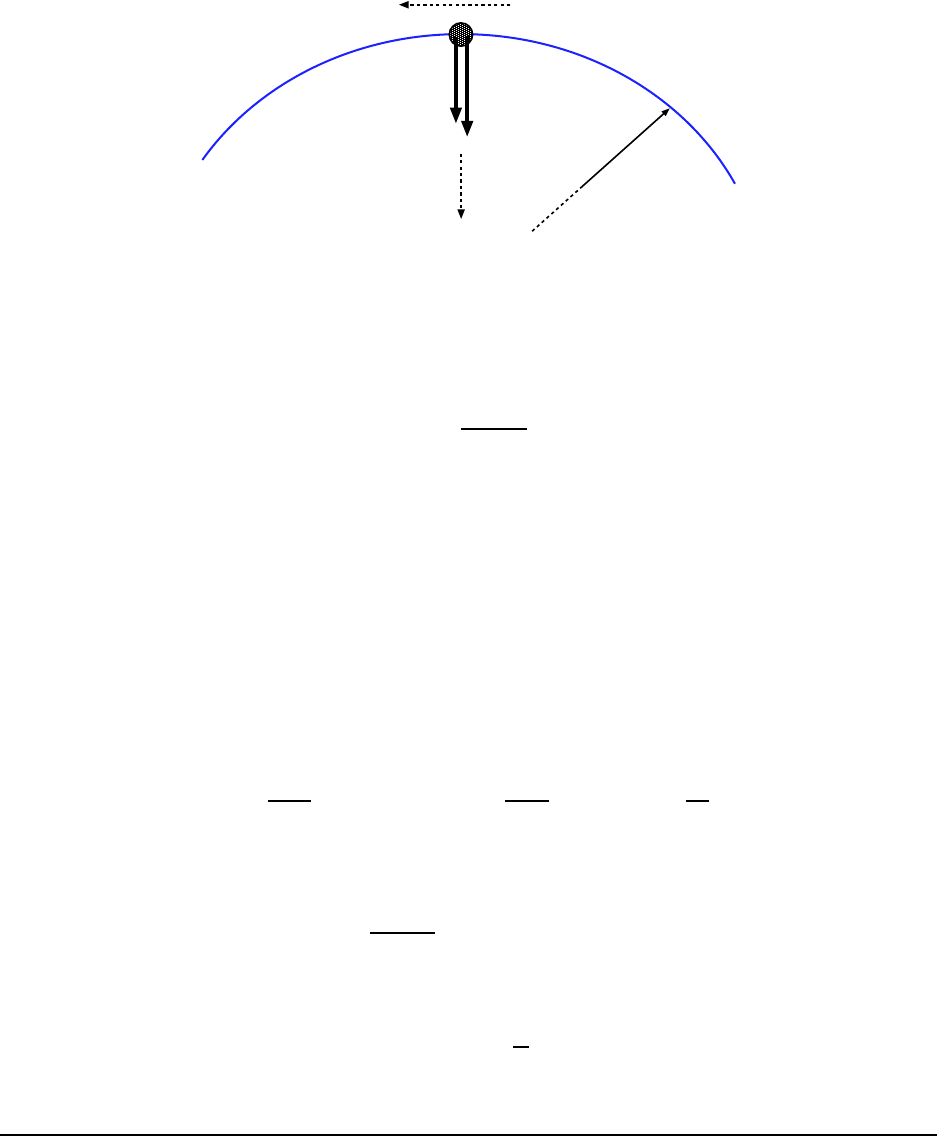

(a) The condition of the pendulum when the stone passes the lowest p oi nt is shown in

Fig. 6. 8(a). Throughout the problem we will measure the height y of the stone from the

6.2. WORKED EXAMPLES 143

60

o

2.0 kg

4.0 m

8.0 m/s

(a)

(b)

v= ?

Figure 6.8: (a) Pendulum in Exa mple 12 swings through lowest point. (b) Pendulum ha s swung 60

◦

past

lowest point.

bottom of its swing. Then at the bottom of the swing the stone has ze r o potential energy,

while its kinetic energy is

K

i

=

1

2

mv

2

0

=

1

2

(2.0 kg)(8.0

m

s

)

2

= 64 J

When the stone has swung up by 60

◦

(as in Fig. 6.8(b)) it has some potential energy. To

figure out how much, we need to calcul ate the height of the stone above the lowest point of

the swing. By simpl e geometry, the stone’s position is

(4.0 m) cos 60

◦

= 2.0 m

down from the top of the string, so it must be

4.0 m − 2.0 m = 2.0 m

up from the lowest point. So its potential energy at this point is

U

f

= mgy = (2. 0 kg)(9.80

m

s

2

)(2.0 m) = 39.2 J

It wil l also have a kinetic energy K

f

=

1

2

mv

2

f

, where v

f

is the final speed.

Now in this system the re are only a conservative force acting on the particl e of interest,

i.e. the stone. (We should note that the string tension also acts on the stone, but sinc e

it always pulls perpendicularly to the motion of the stone, it does no work.) So the total

mechanical energy of the stone is conserved:

K

i

+ U

i

= K

f

+ U

f

We can substitute the values found above to get:

64.0 J + 0 =

1

2

(2.0 kg)v

2

f

+ 39.2 J

which we c an solve for v

f

:

(1.0 kg)v

2

f

= 64.0 J − 39.2 J = 24.8 J =⇒ v

2

f

= 24.8

m

2

s

2

144 CHAPTER 6. WORK, KINETIC ENERGY AND POTENTIAL ENERGY

q

4.0 m

4.0 m

Figure 6. 9: Stone reaches its highest position in the swing, which we specify by some angle θ measured

above the horizontal.

and then:

v

f

= 5.0

m

s

The speed of the stone at the 60

◦

position will be 5.0

m

s

.

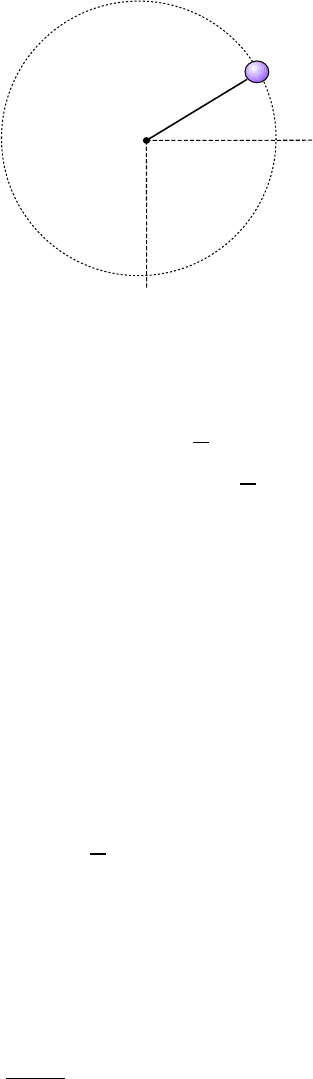

(b) Clearly, since the stone is sti ll in motion at an angle of 60

◦

, it will keep moving to greater

angles and larger hei ghts above the bottom position. For all we know, it may keep rising

until it gets to some angle θ above the p osition where the string is horizontal, as shown

in Fig. 6.9. We do assume that the string wi ll stay straight until this point, but that is a

reasonable assumption.

Now at this point of maximum height, the speed of the mass is instantaneously zero. So

in this final position, the kinetic energy is K

f

= 0. Its height above the starting position i s

y = 4.0 m + (4.0 m) sin θ = (4.0 m)(1 + sin θ) (6.27)

so that its potential energy the re is

U

f

= mgy

f

= (2.0 kg)(9.80

m

s

2

)(4.0 m)(1 + sin θ) = (78.4 J)(1 + sin θ)

We use the conservation of me chanical energy (from the position at the bottom of the swing)

to find θ: K

i

+ U

i

= K

f

+ U

f

, so:

U

f

= K

i

+ U

i

− K

f

=⇒ (78.4 J)(1 + sin θ) = 64 J + 0 − 0

This gives us:

1 + sin θ =

78.4 J

64 J

= 1.225 =⇒ sin θ = 0.225

and finally

θ = 13

◦

We do get a sensible answer of θ so we were right in writing down Eq. 6.27. Actually this

equation would also have been correct if θ were negative and the pendulum reached its

highest point wi th the string below the horizontal.

6.2. WORKED EXAMPLES 145

R

A

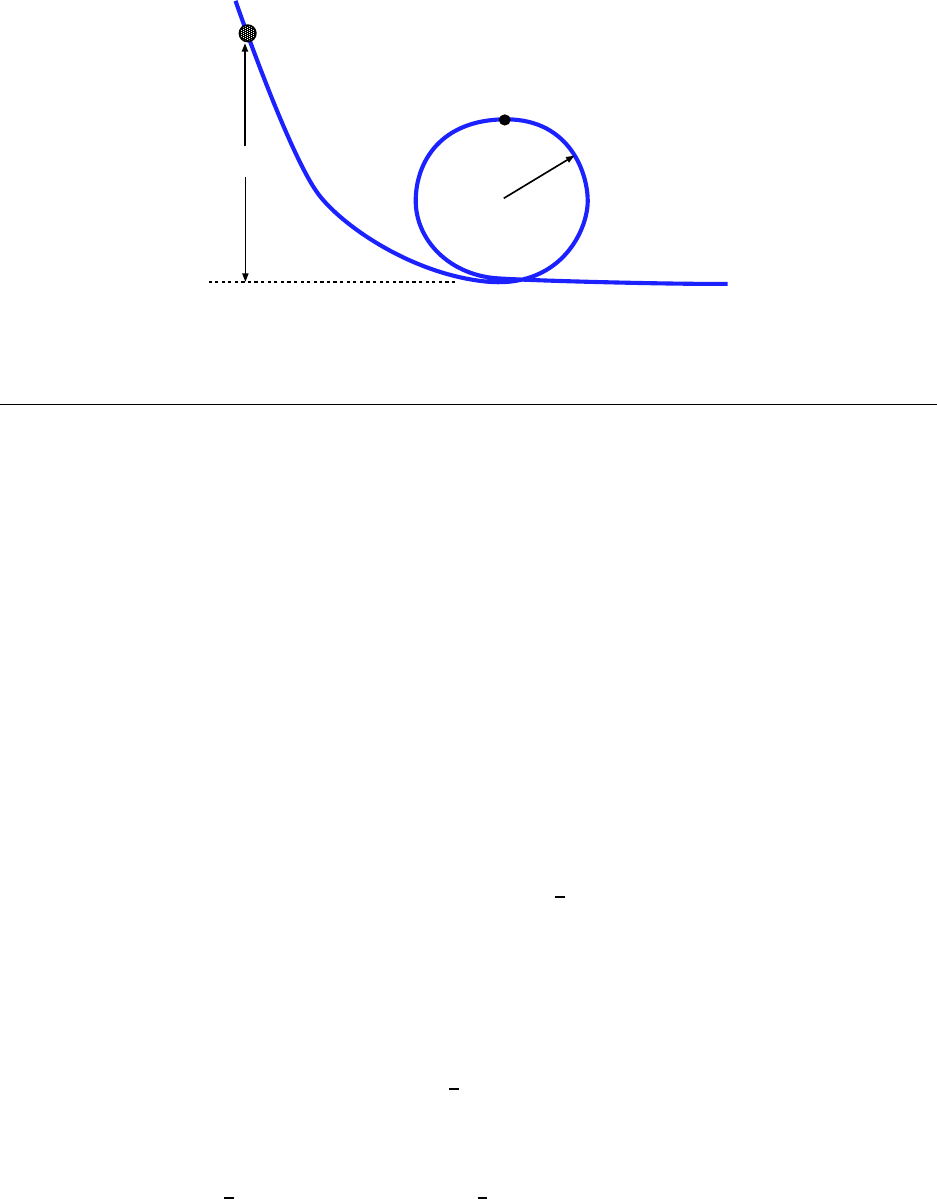

h

Figure 6.10: Bead slides on track in Example 13.

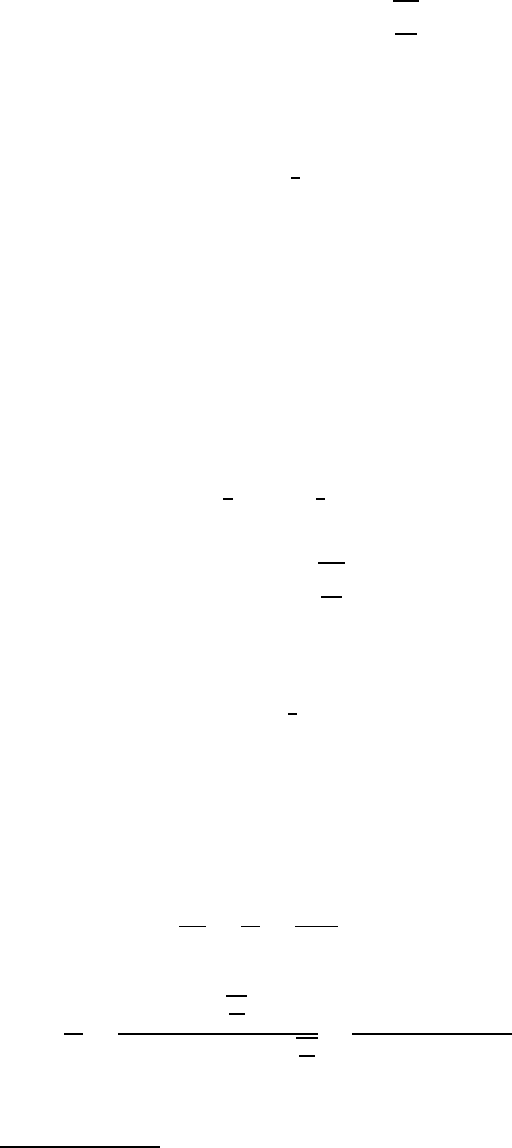

13. A b ead slides wit hout friction on a loop–the –loop track (see Fig. 6.10). If

the bead is rele ase d from a height h = 3.50R, what is its speed at point A? H ow

large is the normal force on it if its mass is 5.00 g? [Ser4 8-11]

In this problem, the r e are no friction forces acting on the particle (the bead). Gravity acts

on it and gravity is a conservative force. The track will exert a norm al forces on the bead,

but this f orce does no work. So the total energy of the bead —kinetic plus (gravitational)

potential energy— will be conserved.

At the initial position, when the bead i s released, the bead has no speed; K

i

= 0. But

it is at a height h above the bottom of the track. If we agree to measure height from the

bottom of the track, then the initial potential energy of t he bead is

U

i

= mgh

where m = 5.00 g is the mass of the bead.

At the final position (A), the bead has both kinetic and potential ene r gy. If the bead’s

speed at A is v, then its final kinetic energy is K

f

=

1

2

mv

2

. At position A its height is 2R

(it is a full diameter above the “ground level” of the tr ack) so its potential energy is

U

f

= mg(2R) = 2mgR .

The total energy of the bead is conserved: K

i

+ U

i

= K

f

+ U

f

. This gives us:

0 + mgh =

1

2

mv

2

+ 2mgR ,

where we want to solve for v (the speed at A). The mass m cancels out, giving:

gh =

1

2

v

2

= 2gR =⇒

1

2

v

2

= gh − 2gR = g(h − 2R)

and then

146 CHAPTER 6. WORK, KINETIC ENERGY AND POTENTIAL ENERGY

R

mg

N

v

Dir. of

accel.

Figure 6.11: Forces acting on the bead when it is at point A (the top of the loop).

v

2

= 2g(h − 2R) = 2g(3.50R − 2R) = 2g(1.5R) = 3.0 gR (6.28)

and finally

v =

q

3.0 gR .

Since we don’t have a numeric al value for R, that’s as far as we can go.

In the next part of the problem, we think about the forces acting on the bead at point A.

These are diagrammed in Fig. 6.11. Gravity pulls down on the bead with a force mg. There

is also a normal force from the track which I have drawn as having a downward component

N. But it is possible for the track to be pushing upward on the bead; if we get a negative

value for N we’ll know t hat the track was pushing up.

At the top of the track the bead is moving on a circular path of radius R, with speed v.

So it is accelerating toward the center o f the circle, namely downward. We know that the

downward forces must add up to give the c entripetal force mv

2

/R:

mg + N =

mv

2

R

=⇒ n =

mv

2

R

− mg = m

v

2

R

− g

!

.

But we can use our result from Eq. 6.28 to substitute for v

2

. This gives:

N = m

3.0 gR

R

− g

= m(2g) = 2mg

Plug in the numbers:

N = 2(5.00 × 10

−3

kg)(9.80

m

s

2

) = 9.80 × 10

−2

N

At point A the t rack is pushing downward with a force of 9.80 × 10

−2

N.

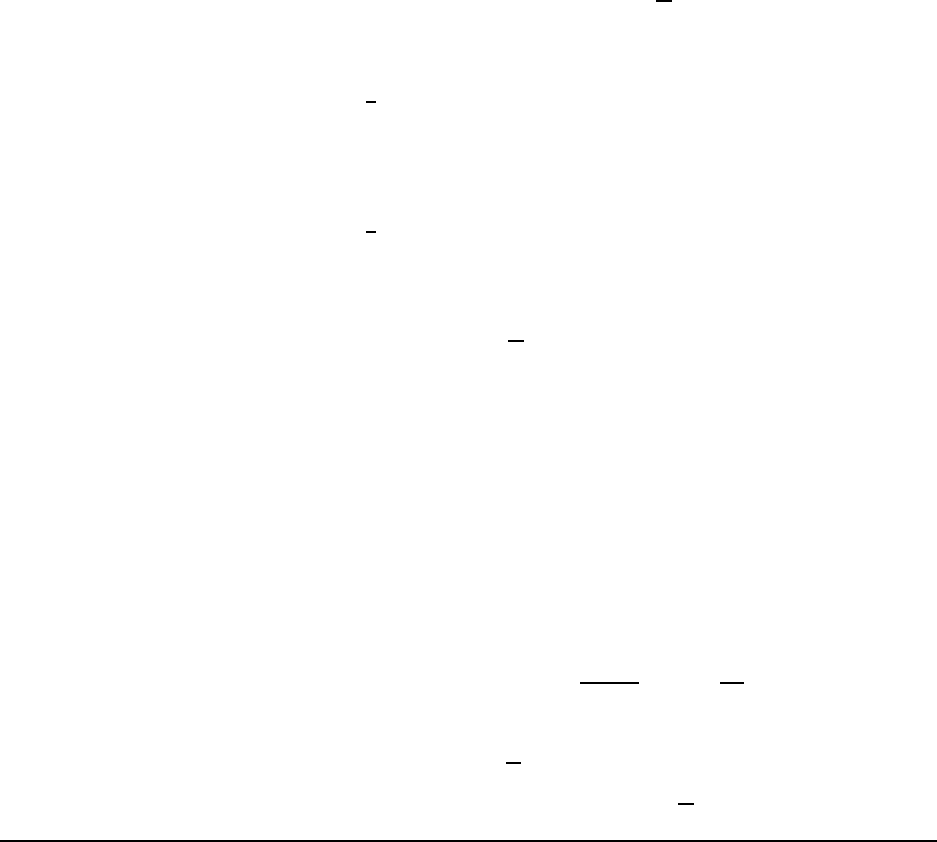

14. Two children are playing a game in which they try to hit a small box on the

floor with a marble fired from a spri ng –loaded gun that is mounted on the table.

The target box is 2.20 m horizontally from the edge of the table; see Fig. 6.12.

6.2. WORKED EXAMPLES 147

2.20 m

Figure 6.12: Spring propels marble off table and hits (or misses) box on the floor.

1.10 cm

v

(a)

(b)

Figure 6.13: Marble propelled by the spring–gun: (a) Spring is compressed, and system has potential

energy. (b) Spring is released and system has kinetic energy of the m arble.

Bobby compresses the spring 1.10 cm, but the center of the marble falls 27.0 cm

short of the center of the box. How far should Rhoda compress the spring to

score a direct hit ? [HRW5 8-36]

Let’s put the origin of our coordinate system (for the motion of the marble) at the edge

of the table. With this choice of coordinates, the object of the game i s to insure that the x

coordinate of the marble is 2.20 m when it reaches the level of the floor.

There are many things we are not told in this problem! We don’t know the spring

constant for the gun, or the mass of the marble. We don’t know the height of the table

above the floor, either!

When the gun propels the marble, the spring is initially compressed and the marble is

motionless ( se e Fig. 6.13(a).) The energy of the system here is the energy stored in the spring,

E

i

=

1

2

kx

2

, where k is the force constant of the spring and x is the amount of compression

of the spring.) When the spring has returned to its natural length and has given the marble

a speed v, then the energy of the system is E

f

=

1

2

mv

2

. If we can neglect friction the n

mechanical energy is conserved during the firing, so that E

f

= E

i

, which gives us:

1

2

mv

2

=

1

2

kx

2

=⇒ v =

s

k

m

x

2

= x

s

k

m

148 CHAPTER 6. WORK, KINETIC ENERGY AND POTENTIAL ENERGY

We will let x and v be the compression and initial marble speed for Bobby’s attempt. Then

we have:

v = (1.10 × 10

−2

m)

s

k

m

(6.29)

The marble’s trip from the edge of the table to the floor is (by now!) a fairly simpl e

kinematics problem. If the time the marble spends in the air is t and the height of the table

is h then the equation for vertical motion tells us:

h =

1

2

gt

2

.

(This is true because the marble’s initial velocity i s all horizo ntal. We do know that on

Bobby’s try, the marble’s x coordinate at impact was

x = 2.20 m − 0.27 m = 1.93 m

and since the horizontal velocity of the marble is v, we have:

vt = 1.93 m . (6.30)

There are too many unknowns to solve for k, v, h and t. . . but let’s go on.

Let’s suppose that Rhoda compresses the spring by an amount x

0

so that the marble is

given a speed v

0

. As before, we have

1

2

mv

0

2

=

1

2

kx

0

2

(it’s the same spri ng and marble so that k and m are the same) and this gives:

v

0

= x

0

s

k

m

. (6.31)

Now when Rhoda’s shot go es off the table and through the air, then if its tim e of flight is t

0

then the equation for vertical m otion gives us:

h =

1

2

gt

0

2

.

This is the same equation as for t, so that the times of flight for both shots is the same:

t

0

= t. Since the x coordinate of the marble for Rhoda’s shot will be x = 2.20 m, the equation

for horizontal motion gives us

v

0

t = 2.20 m (6.32)

What can we do wi t h these equations? If we divide Eq. 6.32 by Eq. 6.30 we get:

v

0

t

vt

=

v

0

v

=

2.20

1.93

= 1.14

If we divide Eq. 6.31 by Eq. 6.29 we get:

v

0

v

=

x

0

q

k

m

(1.10 × 10

−2

m)

q

k

m

=

x

0

(1.10 × 10

−2

m)

.

With these last two results, we can solve for x

0

. Combining these equations gi ves:

1.14 =

x

0

(1.10 × 10

−2

m)

=⇒ x

0

= 1.14(1.10 × 10

−2

m) = 1.25 cm

Rhoda should compress the spring by 1.25 cm in order to score a direct hit.

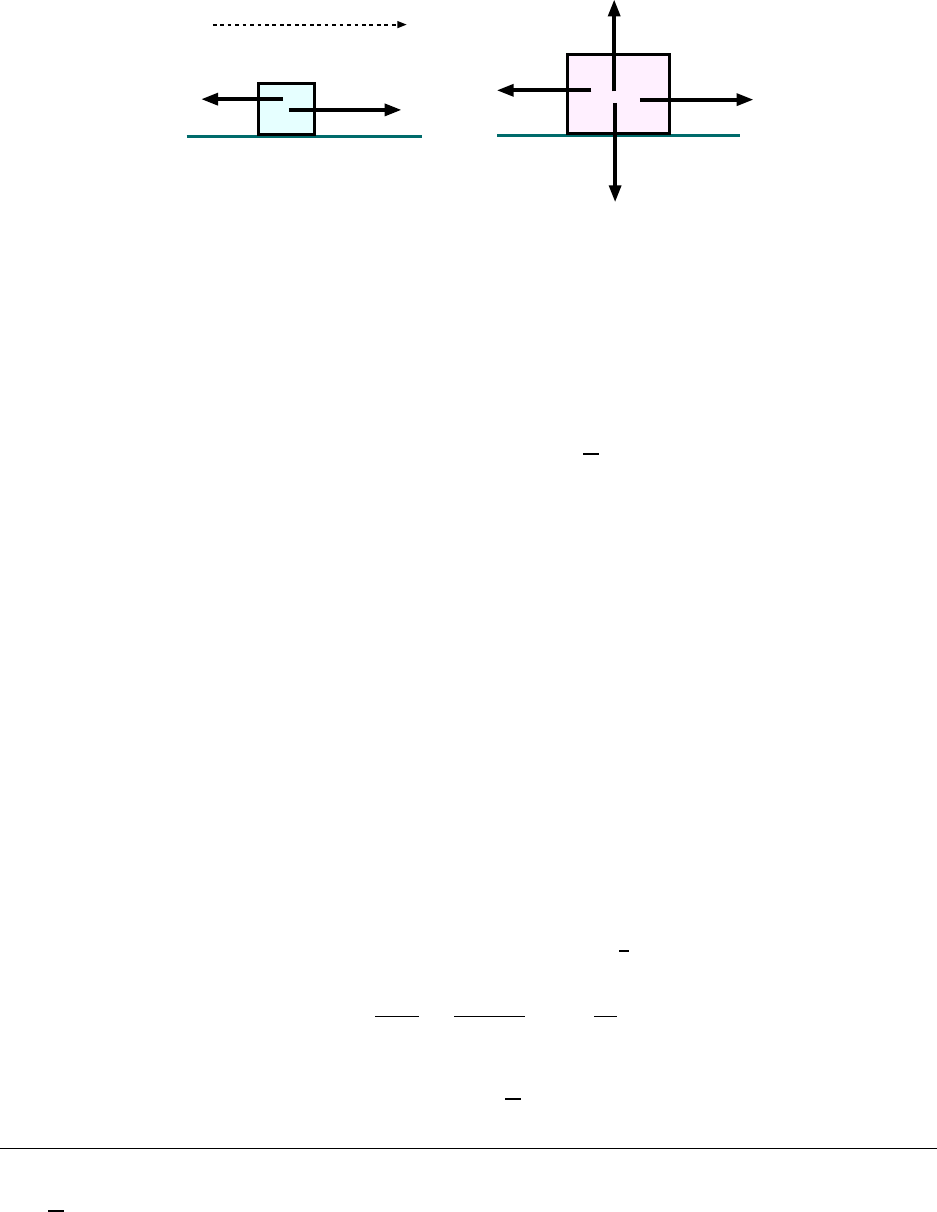

6.2. WORKED EXAMPLES 149

m

k

= 0.40

m= 3.0 kg

M= 5.0 kg

Figure 6.14: Moving masses in Example 15. There is friction between the surface and the 3.0 kg mass.

mg

N

T

f

k

d

d

(a)

(b)

Figure 6.15: (a) Forces acting on m. (b) Masses m and M travel a distance d = 1.5 m as they increase in

speed from 0 to v.

6.2 .7 Work Done by N on–Conservative Forces

15. The coefficient of friction between the 3.0 kg mass and surface in Fig. 6.14 is

0.40. The system starts from rest. What is the speed of the 5.0 k g mass when it

has fal len 1.5 m? [Ser4 8-25]

When the syste m starts to move, both m asses accelerate; because the masses are con-

nected by a string, they always have the same speed . The block (m) sl ides on the rough

surface, and friction does work on it. Since its height do es not change, its potential energy

does not change, but its kinet ic energy increases. The hanging mass (M) drops freely; its

potential energy decreases but its kinetic energy increases.

We want to use energy principles to work this problem; since there i s friction present,

we need to calculate the work done by friction.

The forces acting on m are shown in Fig. 6.15(a). The normal f orce N must be equal to

mg, so the force of kinetic friction on m has magnitude µ

k

N = µ

k

mg. This f orce opposes

150 CHAPTER 6. WORK, KINETIC ENERGY AND POTENTIAL ENERGY

the motion as m moves a distance d = 1.5 m, so the work done by friction is

W

fric

= f

k

d cos φ = (µ

k

mg)(d)(−1) = −(0.40)(3.0 kg)(9.80

m

s

2

)(1.5 m) = −17.6 J .

Mass m’s init ial speed is zero, and its final speed is v. So its change in kinetic energy is

∆K =

1

2

(3.0 kg)v

2

− 0 = (1.5 kg)v

2

As we noted, m has no change in potential energy during the motion.

Mass M’s change in kinetic energy is

∆K =

1

2

(5.0 kg)v

2

− 0 = (2.5 kg)v

2

and since it has a change in height given by −d, its change in (gravitational) potential energy

is

∆U = Mg∆y = (5.0 kg)(9.80

m

s

2

)(−1.5 m) = −73.5 J

Adding up the changes for both masses, the total change in mechanical e nergy of this system

is

∆E = (1.5 kg)v

2

+ (2.5 kg)v

2

− 73.5 J

= (4.0 kg)v

2

− 73.5 J

Now use ∆E = W

fric

and get:

(4.0 kg)v

2

− 73.5 J = −17.6 J

Solve for v:

(4.0 kg)v

2

= 55.9 J =⇒ v

2

=

55.9 J

4.0 kg

= 14.0

m

2

s

2

which gives

v = 3.74

m

s

The final speed of the 5. 0 kg mass (in fact of both masses) is 3.74

m

s

.

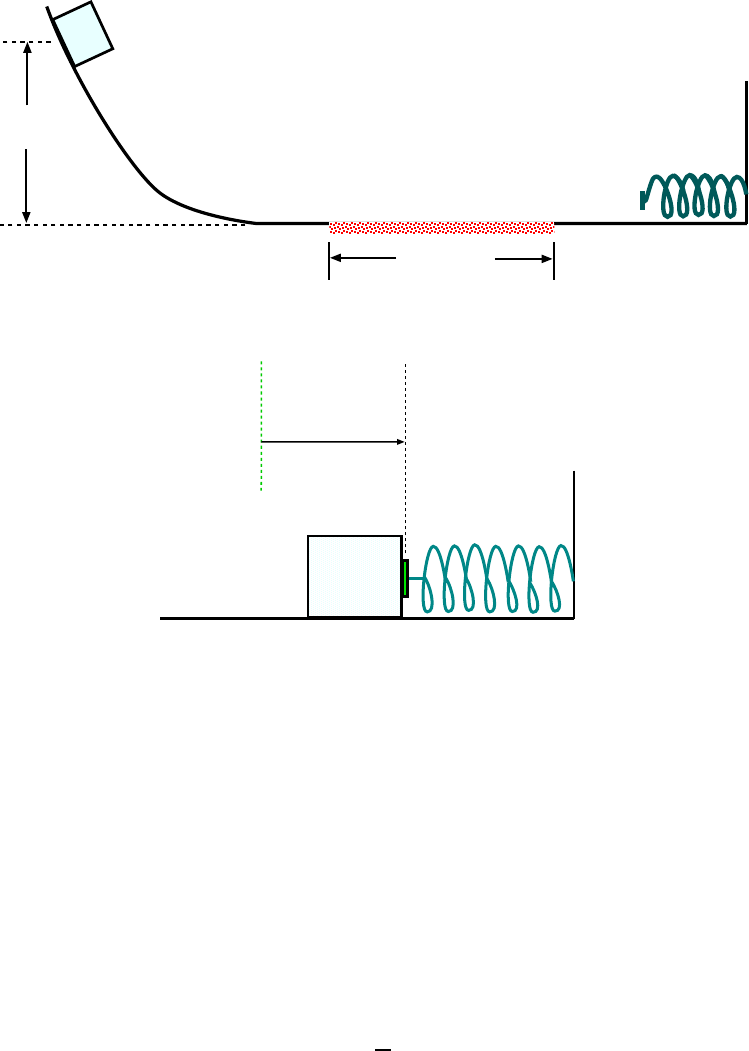

16. A 10.0 kg block is released from point A in Fig. 6.16. The track is fric tion-

less except for the portion BC, of length 6.00 m. The block travels down the

track, hits a spring of forc e constant k = 2250 N/ m, and c ompresses it 0.300 m

from its equilibrium position before coming to rest momentarily. Determine the

coefficient of kinetic friction between surface BC and block. [Ser4 8-35]

We know that we m ust use energy met hods to solve this problem, since the path of the

sliding mass is curvy.

The forces which act on the mass as it descends and goes on to squish the spring are:

gravity, the spring force and the force of kine tic friction as it slides over the rough part.

Gravity and the spring force are c onservative forces, so we will keep track of the m with the

potential energy associated with these force s. Friction is a non-conservative force, but in

6.2. WORKED EXAMPLES 151

6.00 m

B

C

A

3.00 m

10.0 kg

k

Figure 6.16: System for Example 16

0.300 m

v = 0

Equil. pos.

of spring

Figure 6.17: After sliding down the slope and going over the rough part, the m ass has maximally squished

the spring by an amount x = 0.3 00 m.

this case we can calculate the work that it does. Then, we can use the energy conservation

princi ple,

∆K + ∆ U = W

non−con s

(6.33)

to find the unknown quantity in this problem, namely µ

k

for the rough surface. We can

get the answer from t his equation because we have numbers for all the quantities except for

W

non−con s

= W

friction

which depends on the coeffic ient of friction.

The block is released at point A so i t s ini t ial speed (and hence, kinetic energy) is zero:

K

i

= 0. If we m easure height upwards from the l evel part of the track, then the initial

potential energy for the mass (all of it gravitational) is

U

i

= mgh = (10.0 kg)(9.80

m

s

2

)(3.00 m) = 2.94 × 10

2

J

Next , for the “final” position of the mass, consider the time at which it has maximally

compressed the spring and it is (instantaneously) at rest. (This is shown in Fig. 6.17.) We

don’t need to think about what the mass was doing in between these two points; we don’t

care about the speed of the mass during its slide.

At thi s final point, the m ass is again at rest, so its kinetic e ne rgy is zero: K

f

= 0. Being

at zero height, it has no gravitational potential energy but now since there is a compressed

152 CHAPTER 6. WORK, KINETIC ENERGY AND POTENTIAL ENERGY

spring, there is stored (potential) energy in the spring. This energy is given by:

U

spring

=

1

2

kx

2

=

1

2

(2250

N

m

)(0.300 m)

2

= 1.01 × 10

2

J

so the final potential energy of t he system is U

f

= 1.01 × 10

2

J.

The total mechanical energy of the system changes because there is a non–conservative

force (friction) which does work. As the mass (m) sl ides over the rough part, the vertic al

forces are gravity (mg, downward) and the upward normal force of the surface, N. As the r e

is no vertic al motion, N = mg. The magnitude of the force of kinetic friction is

f

k

= µ

k

N = µ

k

mg = µ

k

(10.0 kg)(9.80

m

s

2

) = µ

k

(98.0 N)

As the block moves 6.00 m this force points opposite (180

◦

from ) the direction of motion.

So the work done by friction is

W

fric

= f

k

d cos φ = µ

k

(98.0 N)(6.00 m) cos 180

◦

= −µ

k

(5.88 × 10

2

J)

We now have everything we need to substitute into the energy balance c ondition, Eq. 6.33.

We get:

(0 − 0) + (1.01 × 10

2

J − 2.94 × 10

2

J) = −µ

k

(5.88 × 10

2

J) .

The physics is done. We do algebra to solve for µ

k

:

−1.93 × 10

2

J = −µ

k

(5.88 × 10

2

J) =⇒ µ

k

= 0.328

The coefficient of kinetic friction for the rough surface and block is 0.328.

6.2 .8 Relationship Between Cons ervative Forces and Potential En-

ergy (Optional?)

17. A potential energy function for a two–dimensional force is of the form U =

3x

3

y − 7x. Find the force that acts at the point (x, y). [Ser4 8-39]

(We presume that the expression for U wi ll give us U in joules when x and y are in

meter s!)

We use Eq. 6.26 to get F

x

and F

y

:

F

x

= −

∂U

∂x

= −

∂

∂x

(3x

3

y − 7x)

= −(9x

2

y − 7) = −9x

2

y + 7

6.2. WORKED EXAMPLES 153

and:

F

y

= −

∂U

∂y

= −

∂

∂y

(3x

3

y − 7x)

= −(3x

3

) = −3x

3

Then in unit vector form, F is:

F = (−9x

2

y + 7)i + (−3x

3

)j

where, if x and y are in meters then F is in newtons. Got to watch those uni t s!

154 CHAPTER 6. WORK, KINETIC ENERGY AND POTENTIAL ENERGY