Financial

Literacy

Around the

World:

Leora Klapper,

World Bank Development Research Group

Annamaria Lusardi,

The George Washington University School of Business

Peter van Oudheusden,

World Bank Development Research Group

INSIGHTS FROM THE STANDARD & POOR’S

RATINGS SERVICES GLOBAL FINANCIAL

LITERACY SURVEY

The findings, interpretations, and

conclusions expressed in this report

are entirely those of the authors.

They do not necessarily represent the

views of the International Bank for

Reconstruction and Development/

World Bank and its affiliated

organizations or those of the executive

directors of the World Bank or the

governments they represent.

The World Bank does not guarantee

the accuracy of the data included in

this work. The boundaries, colors,

denominations, and other information

shown on any map in this volume do

not imply on the part of the World

Bank Group any judgment on the

legal status of any territory or the

endorsement or acceptance of such

boundaries.

We are grateful for the support

provided by Standard & Poor’s Ratings

Services and its parent company

McGraw Hill Financial Inc, as part of

their ongoing program to highlight

financial literacy as a key component

of robust and sustainable financial

markets around the world.

To download the complete Standard &

Poor’s Ratings Services Global FinLit

Survey and related material, visit

http://www.FinLit.MHFI.com.

This report was authored by Leora Klapper,

Annamaria Lusardi, and Peter van Oudheusden,

with the support of Jake Hess and Saniya Ansar.

Financial

Literacy

around the

World:

INSIGHTS FROM THE S&P GLOBAL FINLIT SURVEY

1. Financial literacy: What it is and why it matters ..................4

2. Summary of the 2014 S&P FinLit Suvey ..................................6

2.1 Lower financial literacy among women

and the poor ...........................................................................12

2.2 Many users of financial products

lack financial skills ................................................................16

2.2.1 Account ownership and savings ..............................16

2.2.2 Credit ...............................................................................19

3. Conclusion .....................................................................................21

FINANCIAL LITERACY AROUND THE WORLD | PAGE 4

1.

Financial literacy: What it is and why it matters

Without an understanding of basic financial

concepts, people are not well equipped to make

decisions related to financial management. People

who are financially literate have the ability to

make informed financial choices regarding saving,

investing, borrowing, and more.

Financial knowledge is especially important in times where increasingly

complex financial products are easily available to a wide range of the

population. For example, with governments in many countries pushing to

boost access to financial services, the number of people with bank accounts

and access to credit products is rising rapidly. Moreover, changes in the

pension landscape transfer decision-making responsibility to participants who

previously relied on their employers or governments for their financial security

after retirement.

Financial ignorance carries significant costs. Consumers who fail to understand

the concept of interest compounding spend more on transaction fees, run up bigger

debts, and incur higher interest rates on loans (Lusardi and Tufano, 2015; Lusardi

and de Bassa Scheresberg, 2013). They also end up borrowing more and saving less

money (Stango and Zinman, 2009). Meanwhile, the potential benefits of financial

literacy are manifold. People with strong financial skills do a better job planning and

saving for retirement (Behrman et al., 2012; Lusardi and Mitchell, 2014). Financially

savvy investors are more likely to diversify risk by spreading funds across several

ventures (Abreu and Mendes, 2010).

Given the many ways financial literacy affects financial behavior (Lusardi and

Mitchell, 2014), it is important to understand the extent of people’s understanding

of basic financial concepts as well as the degree to which financial skills fall

short among groups like women and the poor. The Standard & Poor’s Ratings

Services Global Financial Literacy Survey (S&P Global FinLit Survey) provides

this information across a wide array of countries. It builds on early initiatives by

the International Network on Financial Education (INFE) of the Organization for

Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the World Bank’s Financial

Capability and Household Surveys, the Financial Literacy around the World (FLAT

World) project, and numerous national survey initiatives that collect information on

financial literacy. The survey complements these efforts by delivering the first and

most comprehensive global gauge of financial literacy to date.

FINANCIAL LITERACY AROUND THE WORLD | PAGE 5

The information on financial literacy is based on questions added to the Gallup

World Poll survey. More than 150,000 nationally representative and randomly

selected adults in more than 140 economies were interviewed during the 2014

calendar year. The surveys were conducted face-to-face in economies where less

than 80 percent of the population has access to a telephone or is the customary

methodology. The target population consists of the entire population aged 15

and above, aside from prisoners and soldiers.

Financial literacy was measured using questions assessing basic knowledge of

four fundamental concepts in financial decision-making: knowledge of interest

rates, interest compounding, inflation, and risk diversification. The S&P Global

FinLit Survey findings are sobering. Worldwide, only 1-in-3 adults are financially

literate. Not only is financial illiteracy widespread, but there are big variations

among countries and groups. For example, women, the poor, and lower educated

respondents are more likely to suffer from gaps in financial knowledge. This is

true not only in developing economies but also in countries with well-developed

financial markets. People with relatively high financial literacy also tend to have

a few things in common, regardless of where they live. Adults who use formal

financial services like bank accounts and credit cards generally have higher

financial knowledge, regardless of their income. Even poor people who have

a bank account are more likely to be financially literate than poor people who

do not have a bank account, and rich adults who use credit also generally have

better financial skills than rich adults who do not. This suggests the relationship

between financial knowledge and financial services may work in two directions:

While higher financial literacy might lead to broader financial inclusion,

operating an account or using credit may also deepen consumers’ financial skills.

The S&P Global FinLit Survey can be used by academics, regulators,

policymakers, and funders to gauge financial literacy across the globe. By

showing where financial skills are strong and where they are lacking, these new

data can help stakeholders design policies and programs to improve the financial

well-being of individuals around the world.

FINANCIAL LITERACY AROUND THE WORLD | PAGE 6

2.

Country-level nancial literacy ranges from

71 percent to 13 percent

In the S&P Global FinLit Survey, the literacy

questions that measure the four fundamental

concepts for financial decision-making—basic

numeracy, interest compounding, inflation,

and risk diversification—are as follows. (The

answer options are in the brackets, with the

correct answer in bold.)

RISK DIVERSIFICATION

Suppose you have some money. Is it safer to put your money into one business

or investment, or to put your money into multiple businesses or investments?

[one business or investment; multiple businesses or investments; don’t

know; refused to answer]

INFLATION

Suppose over the next 10 years the prices of the things you buy double. If your

income also doubles, will you be able to buy less than you can buy today, the

same as you can buy today, or more than you can buy today? [less; the same;

more; don’t know; refused to answer]

NUMERACY (INTEREST)

Suppose you need to borrow 100 US dollars. Which is the lower amount to pay

back: 105 US dollars or 100 US dollars plus three percent? [105 US dollars; 100

US dollars plus three percent; don’t know; refused to answer]

COMPOUND INTEREST

Suppose you put money in the bank for two years and the bank agrees to add

15 percent per year to your account. Will the bank add more money to your

account the second year than it did the first year, or will it add the same amount

of money both years? [more; the same; don’t know; refused to answer]

Suppose you had 100 US dollars in a savings account and the bank adds 10

percent per year to the account. How much money would you have in the

account after five years if you did not remove any money from the account?

[more than 150 dollars; exactly 150 dollars; less than 150 dollars; don’t know;

refused to answer]

FINANCIAL LITERACY AROUND THE WORLD | PAGE 7

A person is defined as financially literate when he or she correctly answers at

least three out of the four financial concepts described above. We choose this

definition because the concepts are basic and this is what would correspond

to a passing grade. Based on this definition, 33 percent of adults worldwide

are financially literate. This means that around 3.5 billion adults globally, most

of them in developing economies, lack an understanding of basic financial

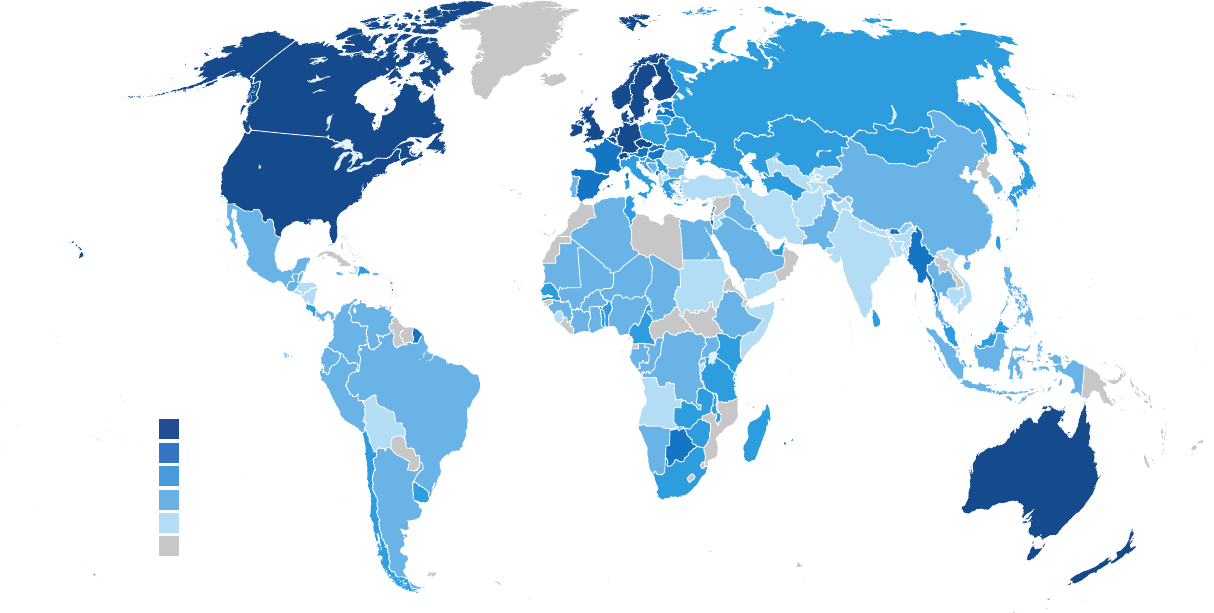

concepts. These global figures conceal deep disparities around the world

(Map 1).

MAP 1: GLOBAL VARIATIONS IN FINANCIAL LITERACY

(% OF ADULTS WHO ARE FINANCIALLY LITERATE)

Source: S&P Global FinLit Survey

The countries with the highest financial literacy rates are Australia, Canada,

Denmark, Finland, Germany, Israel, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and

the United Kingdom, where about 65 percent or more of adults are financially

literate. On the other end of the spectrum, South Asia is home to countries with

some of the lowest financial literacy scores, where only a quarter of adults—or

fewer—are financially literate.

55-75

45-54

35-44

25-34

0-24

No data

FINANCIAL LITERACY AROUND THE WORLD | PAGE 8

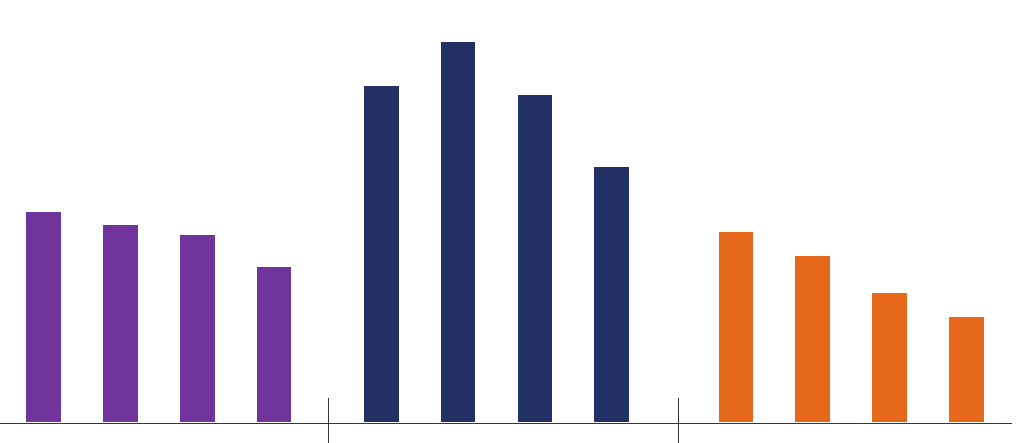

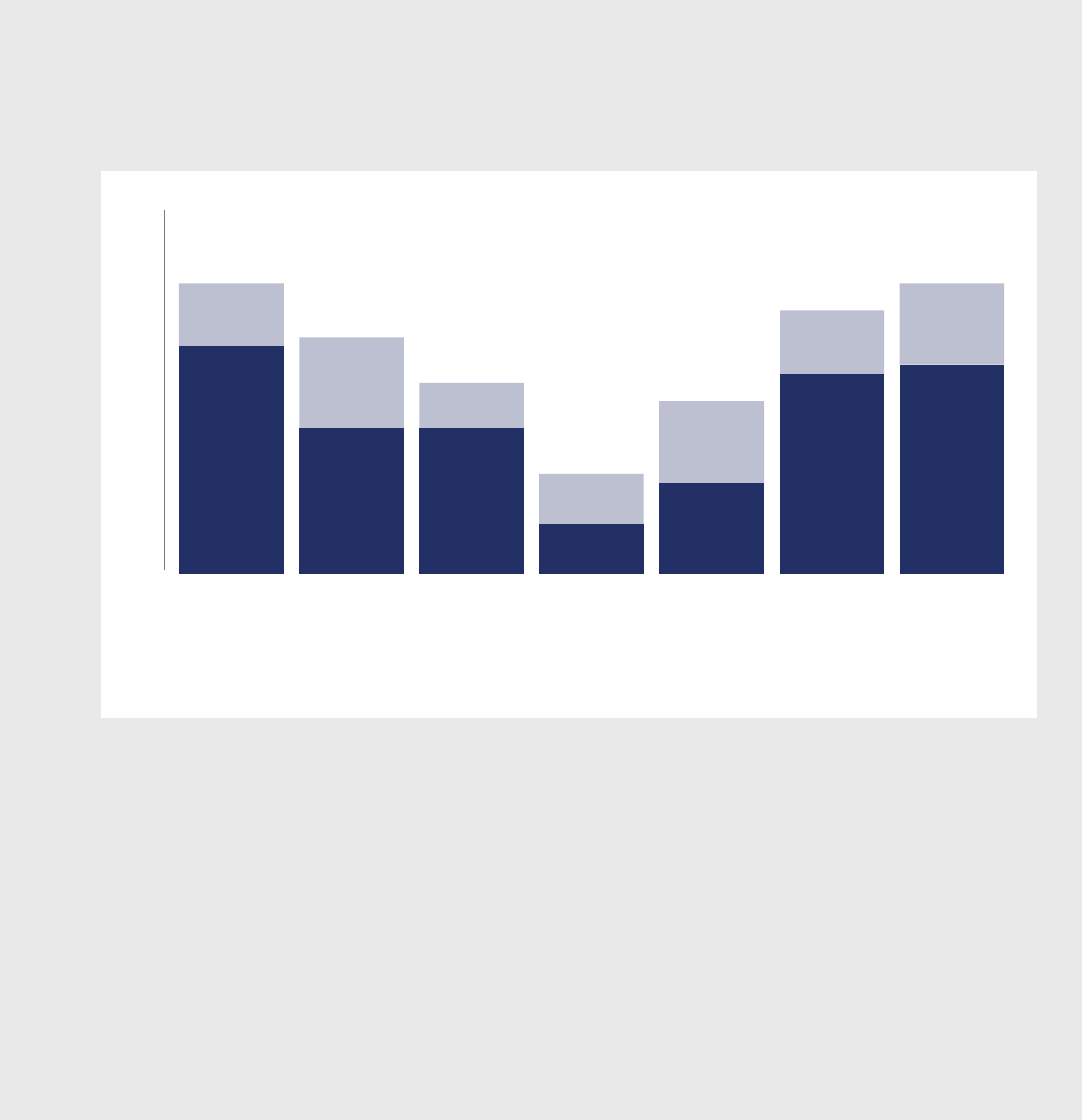

Not surprisingly, financial literacy rates differ enormously between the major

advanced and emerging economies in the world. On average, 55 percent of

adults in the major advanced economies–Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan,

the United Kingdom, and the United States–are financially literate (Figure 1). But

even across these countries, financial literacy rates range widely, from 37 percent

in Italy to 68 percent in Canada.

In contrast, in the major emerging economies—the so-called BRICS (Brazil, the

Russian Federation, India, China, and South Africa)—on average, 28 percent of

adults are financially literate. Disparities exist among these countries, too, with

rates ranging from 24 percent in India to 42 percent in South Africa.

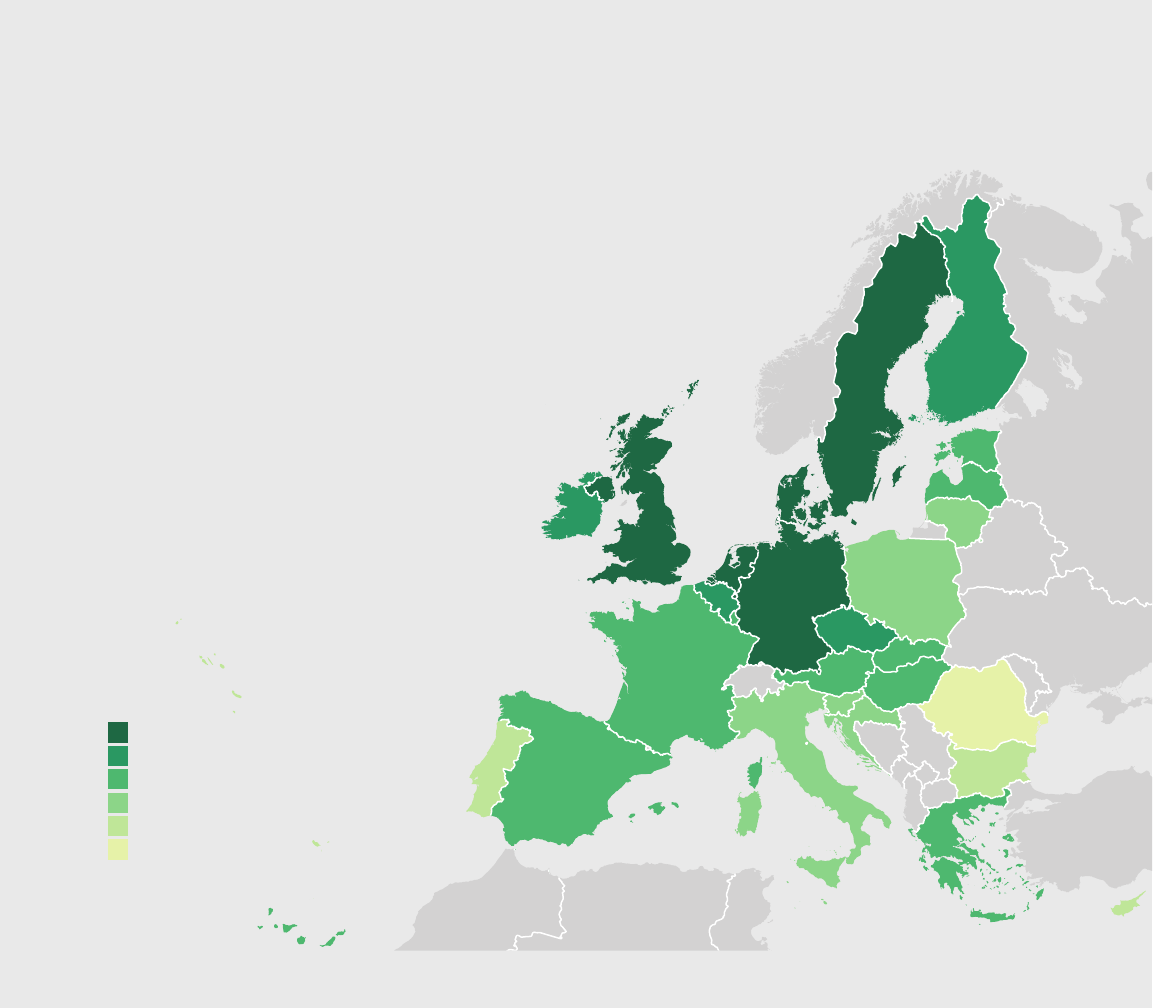

BOX 1: A DIVIDED EUROPEAN UNION

MAP 2: NORTHERN EUROPE LEADS IN FINANCIAL LITERACY

(% OF ADULTS WHO ARE FINANCIALLY LITERATE)

Financial literacy rates vary widely across

the European Union (Map 2). On average, 52

percent of adults are financially literate, and the

understanding of financial concepts is the highest

in northern Europe. Denmark, Germany, the

Netherlands, and Sweden have the highest literacy

rates in the European Union: at least 65 percent of

their adults are financially literate. Rates are much

lower in southern Europe. For example, in Greece

and Spain, literacy rates are 45 percent and 49

percent, respectively. Italy and Portugal have some

of the lowest literacy rates in the south. Financial

literacy rates are also low among the countries

that joined the EU in 2004 and after. In Bulgaria

and Cyprus, 35 percent of adults are financially

literate. Romania, with 22 percent financial literacy,

has the lowest rate in the European Union.

65-75

25-34

45-54

55-64

0-24

35-44

Source: S&P Global FinLit Survey

Major advanced economies Major emerging economies

Canada

France

Germany

China

Italy

India

United States

Brazil

Russian Federation

South Africa

Japan

United Kingdom

0%

40%

20%

60%

80%

0%

40%

20%

60%

80%

FIGURE 1: WIDE VARIATION IN FINANCIAL LITERACY AROUND THE WORLD

(% OF ADULTS WHO ARE FINANCIALLY LITERATE)

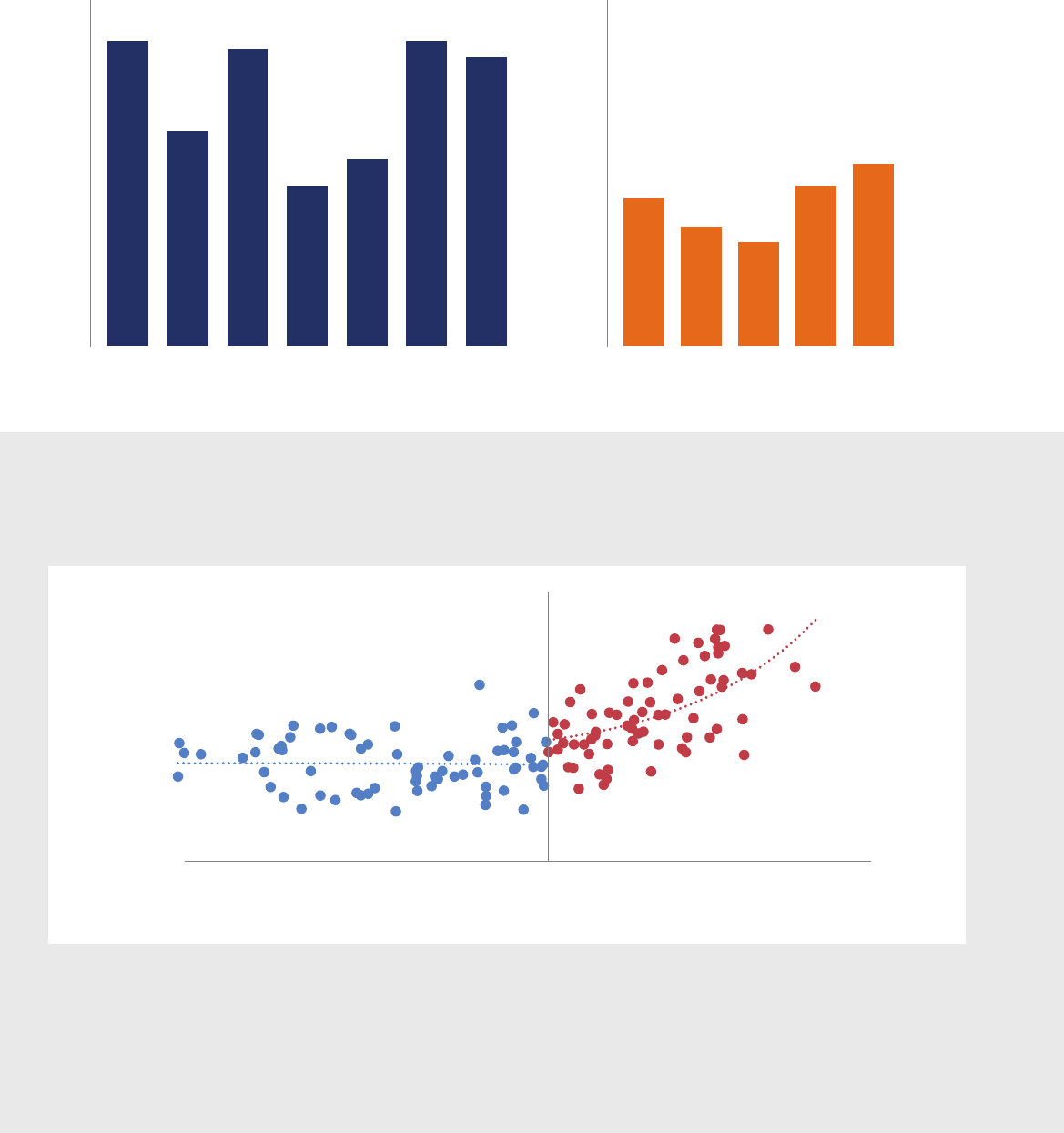

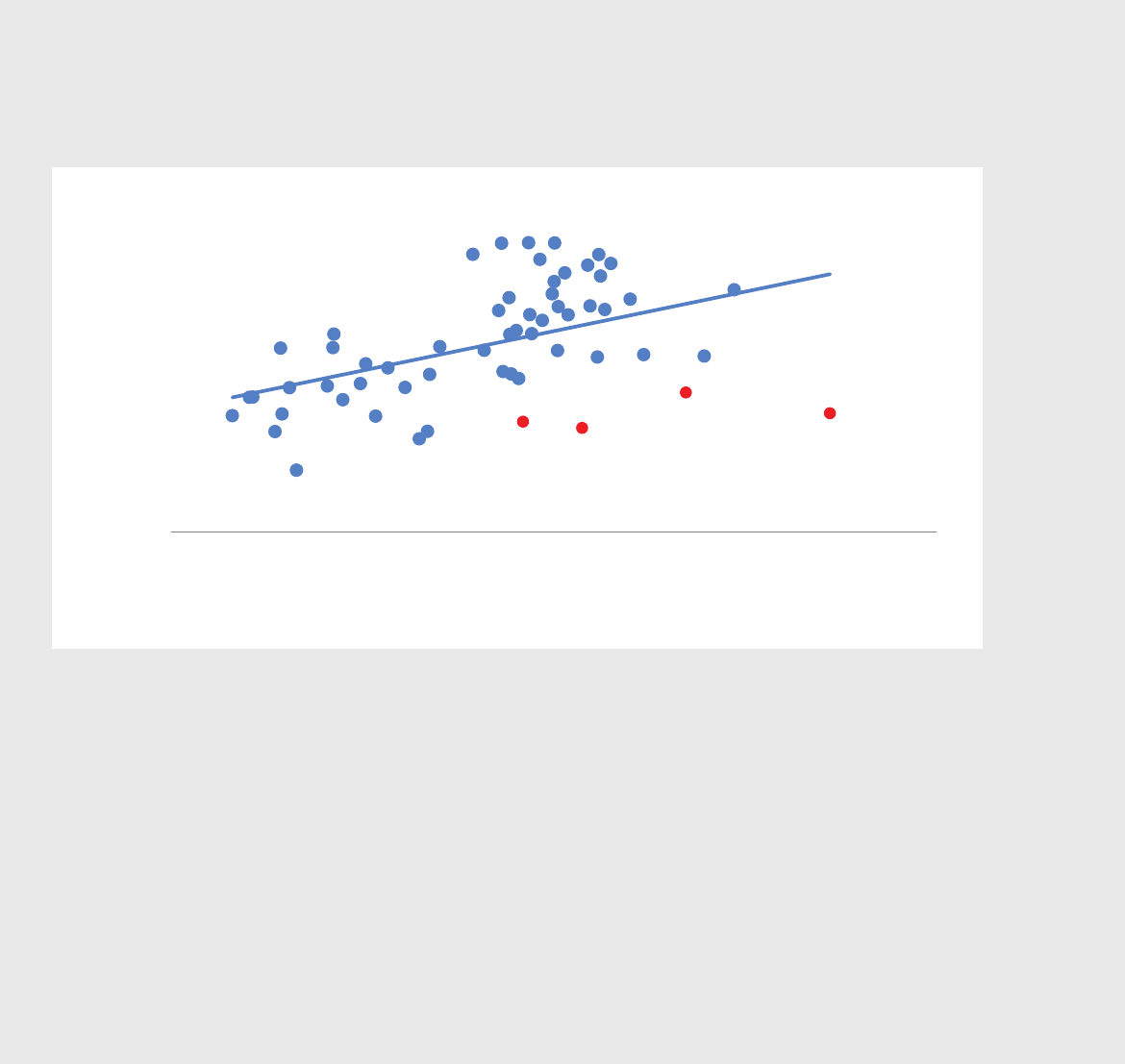

Does income explain worldwide differences in financial literacy? In richer countries, proxied by GDP per capita, financial

literacy rates tend to be higher (Figure 2). However, the relationship only holds when looking at the richest 50 percent of

economies. In these economies, around 38 percent of the variation in financial literacy rates can be explained by differences

in income across countries. For the poorer half of economies, with a GDP per capita of $12,000 or less, there is no evidence

that income is associated with financial literacy. What this likely means is that national-level policies, such as those related to

education and consumer protection, shape financial literacy in these economies more than any other factor.

Source: S&P Global FinLit Survey

FINANCIAL LITERACY AROUND THE WORLD | PAGE 9

BOX 2: GDP PER CAPITA AND FINANCIAL LITERACY

FIGURE 2: HIGH ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT TIED TO HIGH FINANCIAL LITERACY

Source: S&P Global FinLit Survey and Global Findex database.

0%

700 7,000 12,000 70,000

40%

20%

60%

80%

Financial literacy rate

Poorest 50% Richest 50%

GDP per capita

FINANCIAL LITERACY AROUND THE WORLD | PAGE 10

Among the four topics that define financial literacy, inflation and numeracy (in

the context of interest rate calculations) are the most understood. Worldwide,

half the adult population understands these concepts. Knowledge of risk

diversification is the lowest, with only 35 percent of adults correctly answering

that survey question. Risk diversification also figures into some of the largest

disparities among countries. In the major advanced economies, 64 percent of

respondents have an understanding of this concept, against 28 percent in the

major emerging economies (Figure 3). Differences for the other concepts are less

pronounced, ranging from 15 percentage points for inflation to 10 percentage

points for the compound interest concept.

FIGURE 3: STRONGER GRASP OF FINANCIAL CONCEPTS

IN ADVANCED ECONOMIES

(% OF ADULTS WITH CORRECT ANSWERS)

Source: S&P Global FinLit Survey

Note: Major advanced and emerging economies are listed in Figure 1.

RISK DIVERSIFICATION

INFLATION COMPOUND INTEREST

40%20%0% 60% 40%20%0% 60%

40%20%0% 60% 40%20%0% 60%

NUMERACY (INTEREST)

World

Major advanced economies

Major emerging economies

FINANCIAL LITERACY AROUND THE WORLD | PAGE 11

BOX 3: MEMORIES OF INFLATION

FIGURE 4: UNDERSTANDING OF INFLATION HIGHER IN COUNTRIES WITH

RECENT HISTORY OF INFLATION

(% OF ADULTS WITH CORRECT ANSWERS)

People may have a better understanding of financial

concepts when they are confronted with them in their daily

lives. The importance of experience is observed in countries

that saw periods of hyperinflation. For example, Argentina

struggled with hyperinflation in the late 1980s and early

1990s. At its peak, it took less than 20 days for prices to

double (Hanke and Krus, 2013). This experience is reflected

in their knowledge. While their overall financial literacy rate

of 28 percent is lower than the world average, 65 percent

of Argentine adults have an understanding of inflation,

exceeding the world average (Figure 4). Similar patterns are

observed in Georgia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Peru, all

of which experienced hyperinflation in the 1990s.

Source: S&P Global FinLit Survey

3 out of 4 topics correct Ination topic correct

World

Bosnia and Herzegovina

40%

20%

80%

60%

0%

Argentina

40%

20%

80%

60%

0%

FINANCIAL LITERACY AROUND THE WORLD | PAGE 12

2.1

Lower nancial literacy among women

and the poor

Financial literacy rates differ in important ways when it comes to characteristics

such as gender, education level, income, and age. Worldwide, 35 percent of men

are financially literate, compared with 30 percent of women. While women are

less likely to provide correct answers to the financial literacy questions, they

are also more likely to indicate that they “don’t know” the answer, a finding

consistently observed in other studies as well (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2014).

This gender gap is found in both advanced economies and emerging economies

(Figure 5). Women have weaker financial skills than men even considering

variations in age, country, education, and income.

The average gender gap in financial literacy in emerging economies is 5

percentage points, not different from the worldwide gap, though it is absent in

China and South Africa (where financial literacy is equally low for women and

men). There is also a gap in financial literacy when looking at relative income

in the BRICS economies. Thirty-one percent of the rich in these economies are

financially literate, compared to only 23 percent of the poor.

FIGURE 5: WOMEN TRAIL MEN IN FINANCIAL LITERACY

(% OF ADULTS WITH CORRECT OR “DON’T KNOW” ANSWERS)

Source: S&P Global FinLit Survey

Note: Major advanced and emerging economies are listed in Figure 1.

average

“don’t know”

response

rates

40%

20%

60%

0%

MAJOR EMERGING

ECONOMIES

3 out of 4

topics correct

40% 40%

20% 20%

60% 60%

0% 0%

MAJOR ADVANCED

ECONOMIES

WORLD

Men

Men

Women

Women

FINANCIAL LITERACY AROUND THE WORLD | PAGE 13

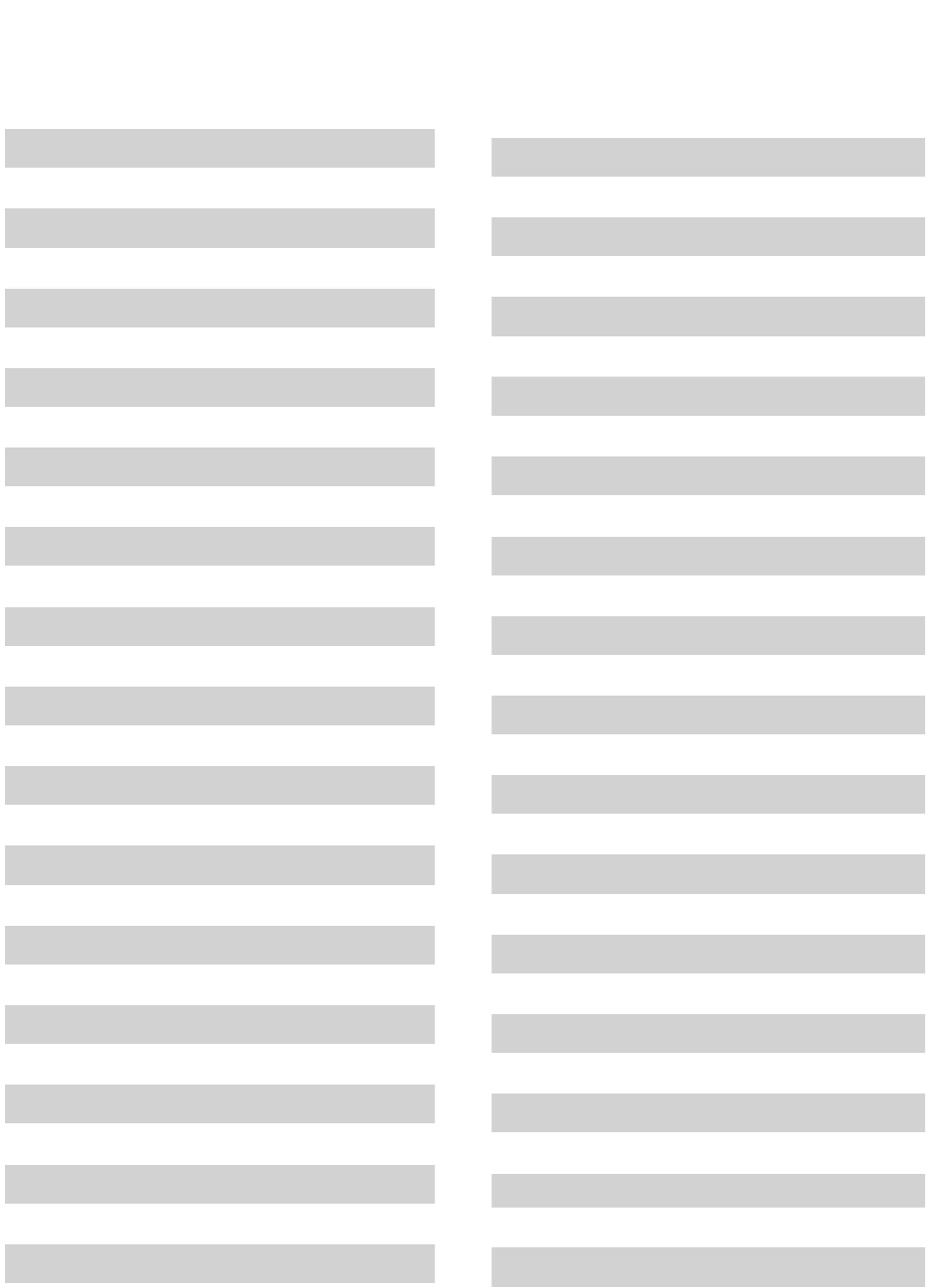

For the major advanced economies, financial literacy rates increase with age

but then later decline with age (i.e., older people or older generations are less

financially literate then middle-age ones). On average, 56 percent of young

adults age 35 or younger are financially literate, compared with 63 percent of

those age 35 to 50. Financial literacy rates are lower for adults older than 50,

and rates are lowest among those older than 65. The pattern is different for

the major emerging economies. In these economies, adults age 65 plus have

the lowest financial literacy rates of any age group, but the young have the

highest knowledge. At 32 percent, financial literacy in these economies is much

higher for young adults than for the oldest adults of whom only 17 percent are

financially literate.

(% OF ADULTS WHO ARE FINANCIALLY LITERATE)

Source: S&P Global FinLit Survey

Note: Major advanced and emerging economies are listed in Figure 1.

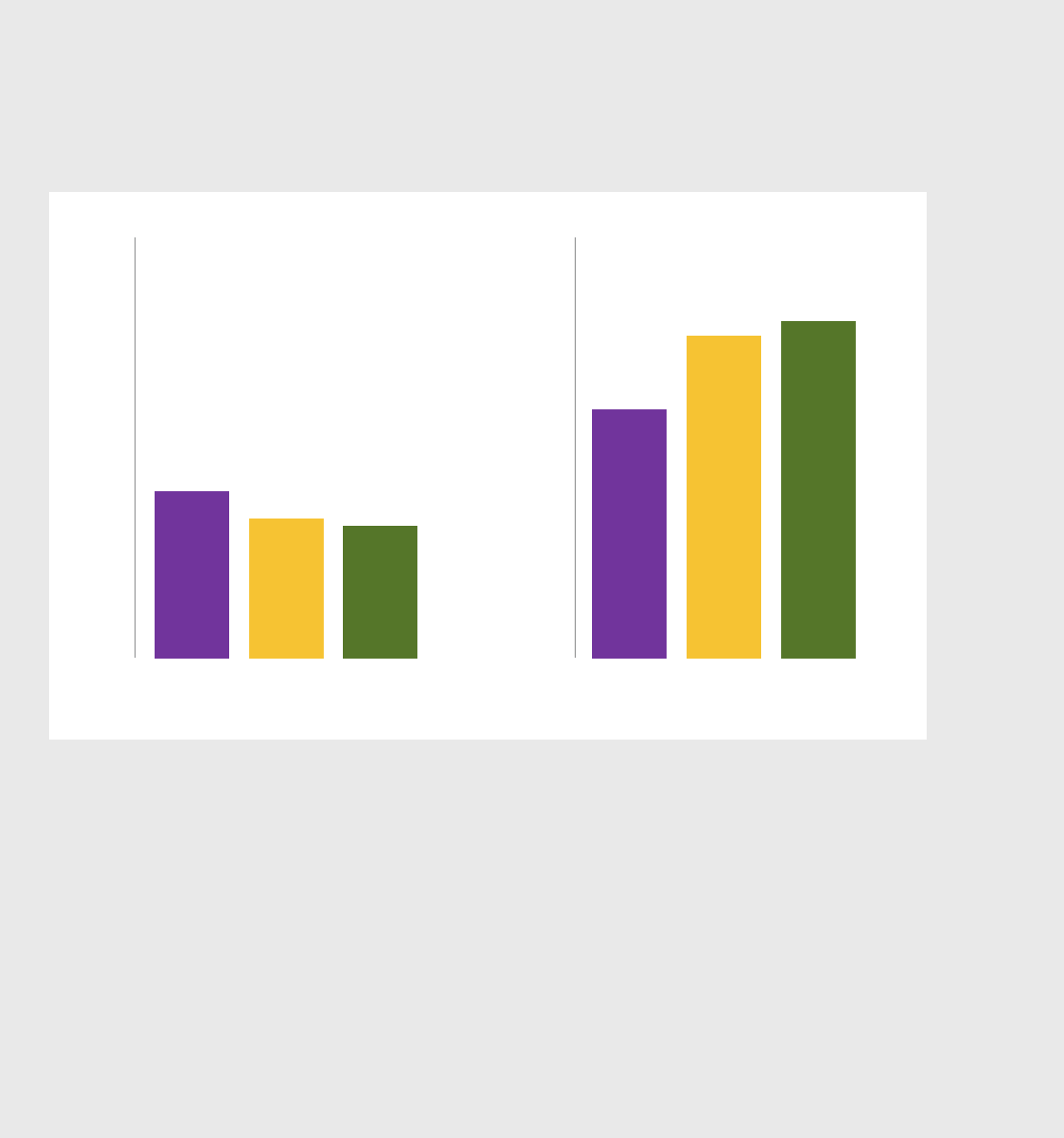

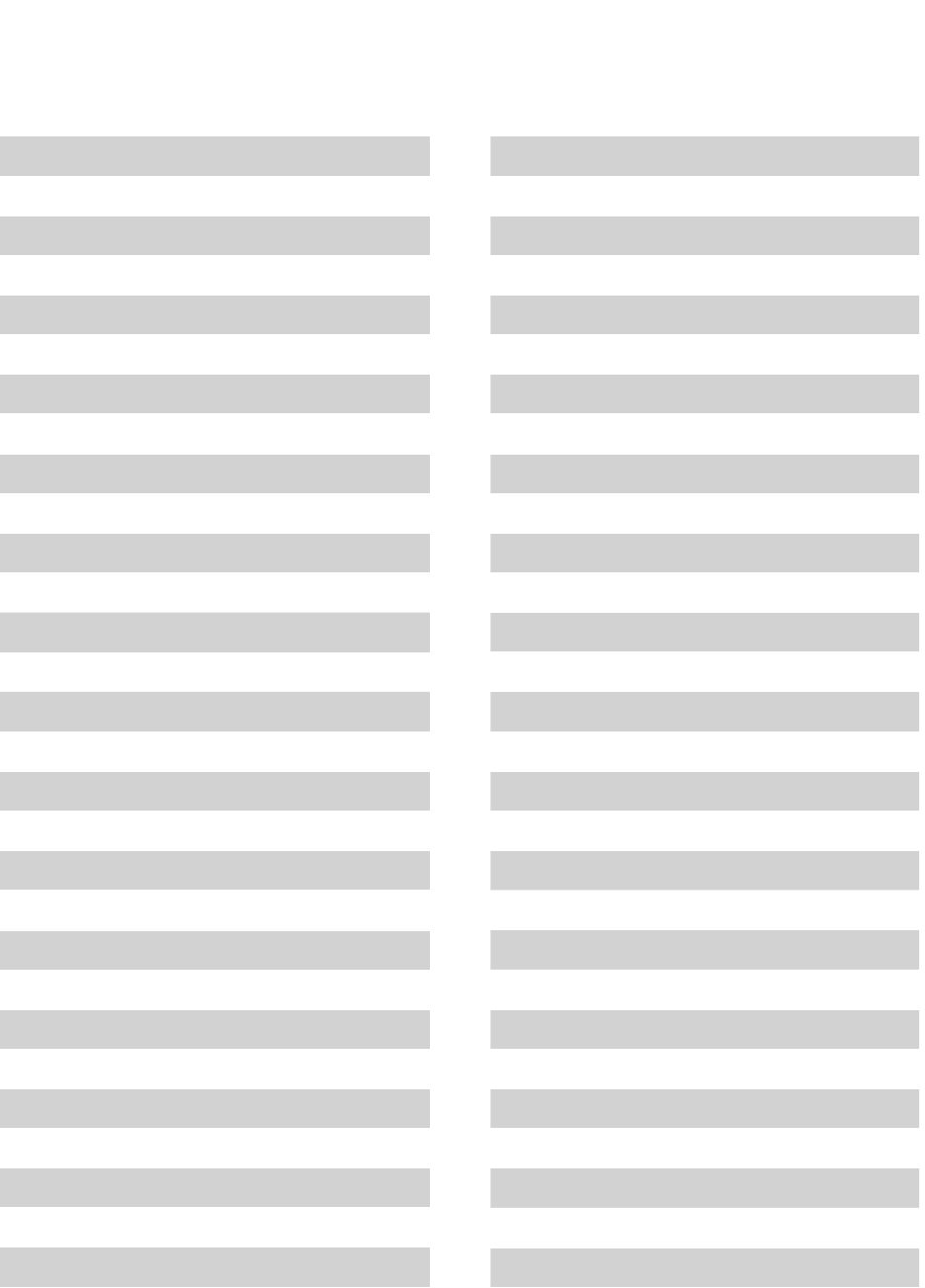

Rich adults have better financial skills than the poor. Of adults living in the

richest 60 percent of households in the major emerging economies, 31 percent

are financially literate, against 23 percent of adults who live in the poorest

40 percent of households. The size of the income gap is similar in the major

advanced economies, but some suffer from even deeper inequality. For example,

in Italy, 44 percent of adults who live in the richest 60 percent of households are

financially literate compared with 27 percent of their counterparts who are poor.

WORLD

40%

20%

60%

0%

Ages

15-35

Ages

36-50

Ages

51-65

Age

65+

MAJOR ADVANCED ECONOMIES

Ages

15-35

Ages

36-50

Ages

51-65

Age

65+

MAJOR EMERGING ECONOMIES

Ages

15-35

Ages

36-50

Ages

51-65

Age

65+

FIGURE 6: FINANCIAL LITERACY LOWEST AMONG ADULTS AGE 65+

FINANCIAL LITERACY AROUND THE WORLD | PAGE 14

FIGURE 7: FINANCIAL LITERACY GROWS WITH INCOME

(% OF ADULTS WHO ARE FINANCIALLY LITERATE)

Source: S&P Global FinLit Survey

Note: Major advanced and emerging economies are listed in Figure 1.

Financial literacy also sharply increases with educational attainment—which

is strongly associated with math skills, as well as age and income. Globally, a

gap of about 15 percentage points separates adults with primary, secondary,

and tertiary education. In major advanced economies, 52 percent of adults

with secondary education—between nine and 15 years of schooling—are

financially literate. Among adults who have primary education—up to eight

years of schooling—that figure is 31 percent. A similar divide separates adults

with secondary education and adults with tertiary education: Among adults with

at least 15 years of schooling, 73 percent are financially literate. The education

gaps are similar in the major emerging economies.

40%

20%

60%

0%

WORLD MAJOR EMERGING

ECONOMIES

Richest 60%

Poorest 40%

MAJOR ADVANCED

ECONOMIES

FINANCIAL LITERACY AROUND THE WORLD | PAGE 15

Overall understanding of financial concepts tends to be high in countries

where 15-year-old students performed well on the OECD’s 2012 Programme

for International Student Assessment (PISA) math test (2014). While overall

there is a positive relationship, some notable outliers are evident (Figure 8). In

China, South Korea, Portugal, and Vietnam, financial literacy rates (proxied by

math scores) are much higher among young adults than older adults. In South

Korea, 48 percent of adults age 35 or younger are financially literate, against 27

percent of adults age 51 to 65. For Portugal these numbers are 38 percent and 20

percent, respectively. These findings suggest that a general proficiency in math

may be beneficial for understanding financial concepts. In some countries, young

people have acquired a high math knowledge that may translate into much

higher financial literacy in adulthood.

Source: S&P Global FinLit Survey and OECD PISA data (2014)

Portugal

Vietnam

China

South Korea

0%

40%

20%

60%

80%

350 450 550400 500

2012 PISA math scores

Financial litearcy rate

600 650

BOX 4: YOUNG, GOOD AT MATH, AND FINANCIALLY LITERATE

FIGURE 8: STRONGER FINANCIAL SKILLS IN COUNTRIES WITH HIGH TEST SCORES

FINANCIAL LITERACY AROUND THE WORLD | PAGE 16

2.2

Many users of nancial products lack nancial skills

Financial literacy skills are important for people who use payment, savings, credit, and risk-

management products. For many, having an account at a bank or other financial institution—

or with a mobile money service provider—is an important first step to participation in

the financial system. Financial literacy skills are important for people who use payment,

savings, credit, and risk-management products. For many, having an account at a bank

or other financial institution—or with a mobile money service provider—is an important

first step to participation in the financial system (Demirguc-Kunt, et al., 2015). Yet access

to financial services is not an end in itself. Rather, it is a means to an end. When people have

financial accounts and use digital payments, they are more able to provide for their families,

save money for the future, and survive economic shocks. Digital payments can also reduce

corruption by increasing transparency, and they help empower women by giving them greater

control over their finances (Klapper and Singer, 2014). But people who lack the knowledge to

effectively use such services can face financial disaster, such as high debt or bankruptcy. It is,

therefore, worth exploring the link between financial services and financial literacy.

2.2.1

Account ownership and savings

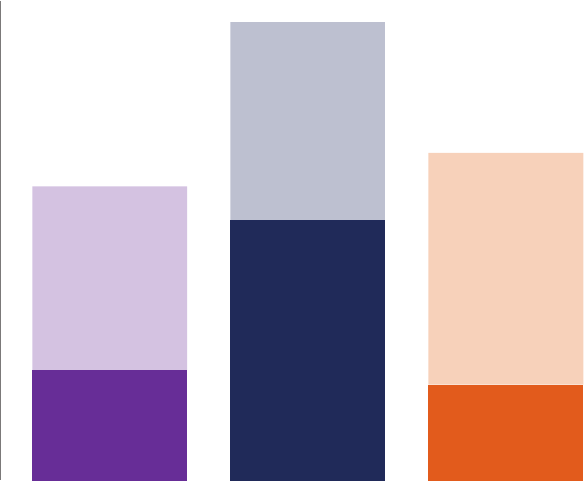

Account owners tend to be more financially savvy, but plenty of them still lack financial skills.

Globally, 38 percent of account-owning adults are financially literate, as are 57 percent of

account owners in major advanced economies and 30 percent in major emerging economies

(Figure 9).

FIGURE 9: ACCOUNT OWNERS OFTEN LACK FINANCIAL SKILLS

(% OF ADULTS WITH AN ACCOUNT)

Source: S&P Global FINLIT Survey and Global Findex database.

Note: The height of the bar is the percentage of adults with an account. Major advanced and emerging economies are listed in Figure 1.

WORLD MAJOR ADVANCED

ECONOMIES

MAJOR EMERGING

ECONOMIES

40%

20%

60%

80%

100%

0%

Financially

literate

Not nancially

literate

FINANCIAL LITERACY AROUND THE WORLD | PAGE 17

Financial literacy gaps exist among account holders even though they generally

have stronger financial skills than the population as a whole. For example, in major

advanced economies, a man with an account is 8 percentage points more likely to

be financially literate than a woman with an account. A similar gap is found between

account owners in the richest 60 percent and poorest 40 percent of households.

Account holders with a primary education are half as likely to be financially literate

as their counterparts with a secondary education.

Account owners who lack financial knowledge may not be fully benefitting from

what their accounts have to offer. One example is savings. Globally, 57 percent

of adults save money, but just 27 percent use a bank or other formal financial

institution to do so. Others use less safe and less lucrative methods, such as informal

savings groups or stuffing cash under a mattress. Only 42 percent of account

owners worldwide use their account to save, and 45 percent of these adult savers

are financially literate. Improving financial literacy might help these savers get a

better deal. For example, about half of account owners in China use their account

to save money, but just 52 percent of them correctly respond to the question about

interest. In the United States, the interest topic is correctly answered by 58 percent

of adults who use formal savings.

Financial skills are even weaker among adults who do not have an account (Figure

10). Globally, 25 percent of these adults are financially literate, as are 22 percent in

major emerging economies.

FIGURE 10: ADULTS WHO LACK AN ACCOUNT ALSO

LACK FINANCIAL SKILLS

(% OF ADULTS WITHOUT AN ACCOUNT)

Source: S&P Global FinLit Survey.

Note: The height of the bar is the percentage of adults without an account. Major advanced and emerging

economies are listed in Figure 1.

20%

10%

30%

40%

0%

WORLD

MAJOR EMERGING

ECONOMIES

Financially

literate

Not nancially

literate

FINANCIAL LITERACY AROUND THE WORLD | PAGE 18

It is difficult to say whether low financial knowledge makes these people less likely

to use financial services. According to the Global Findex, 59 percent of “unbanked”

adults say they do not have enough money to use an account. In reality, most poor

people make payments and other financial transactions every day, but they do so

in informal and often more costly and less safe ways. If they were more aware of

accounts and how they are used, unbanked adults might sign up for an account.

Another possible reason the unbanked lack financial skills is that they do not have

experience using financial products. If they used financial concepts in their daily

lives, their understanding could increase with time. The concept of interest, for

example, would become more concrete as they watched the value of their savings

increase. The most straightforward explanation for low financial skills among the

unbanked is that they come from poorer and less educated households.

Gender, income, and education inequalities also prevail among the unbanked.

Worldwide, 27 percent of unbanked men are financially literate, compared with

22 percent of unbanked women. In major emerging economies, unbanked adults

in the richest 60 percent of households are 5 percentage points more likely to be

financially literate than those in the poorest 40 percent of households. No matter

how the data is spliced, women, the poor, and the lower educated lag behind the

rest of the population.

2.2.2

Credit

Credit is more common in rich countries than poor countries. Many borrowers

in the emerging world are dependent on family and friends or on loans through

informal lenders such as pawnshops and store credit. Access to formal credit is

often confined to the rich and well educated, who tend to be more financially

savvy. In the major advanced economies, 51 percent of adults use a credit card,

compared with only 11 percent of adults in the major emerging economies. A

smaller share of adults borrows from a formal financial institution. Fifty-three

percent of adults in major emerging economies who use a credit card or borrow

from a financial institution are financially literate, much higher than the average

financial literacy rate in these economies.

FINANCIAL LITERACY AROUND THE WORLD | PAGE 19

FIGURE 11: LOW UNDERSTANDING OF INTEREST

PUTS CREDIT USERS AT RISK

(% OF ADULTS WHO USED A CREDIT CARD OR BORROWED FROM

A FINANCIAL INSTITUTION IN THE PAST YEAR)

Source: S&P Global FinLit Survey and Global Findex database.

Note: The height of the bar is the percentage of adults that used a credit card or borrowed from a bank

or other formal financial institution in the past year. Major advanced and emerging economies are listed

in Figure 1.

Credit cards are gaining popularity in many emerging countries, but knowledge

of related financial concepts is not keeping up. Many short-term credit users do

not fully understand the speed at which interest compounding can inflate total

amounts owed (Figure 11). For instance, 32 percent of adults in Brazil have a

credit card, yet 40 percent of them are financially literate and only half correctly

answer the compound interest question. In Turkey, 33 percent of adults have a

credit card, yet just 29 percent of these users are financially literate and only half

understand compound interest.

WORLD MAJOR ADVANCED

ECONOMIES

MAJOR EMERGING

ECONOMIES

20%

10%

30%

40%

50%

0%

Compound

interest correct

Compound

interest

not correct

FINANCIAL LITERACY AROUND THE WORLD | PAGE 20

BOX 5: THE HOMEOWNERS’ EDGE IN FINANCIAL LITERACY

FIGURE 12: HIGH FINANCIAL LITERACY AMONG HOMEOWNERS

(% OF ADULTS WHO HAVE A HOUSING LOAN OUTSTANDING)

In the major advanced economies, 26 percent of adults have an outstanding loan at a financial

institution in order to purchase a home or an apartment. Since paying for a home requires complex

calculations, one would expect homeowners to have stronger financial skills than the average person.

This is, indeed, the case (Figure 12). Nevertheless, some homeowners still suffer from gaps in financial

knowledge and may not understand how quickly their debt can accumulate. In the United States,

almost a third of adults have an outstanding housing loan, and 70 percent of them correctly answer

the compound interest topic. Put differently, 3-in-10 adults with a housing loan are unable to perform

basic interest calculations on their loan payments. Since the global financial crisis was triggered in part

by mortgage defaults in the United States, this should concern policymakers, not just homeowners.

This is not a problem just for the United States: In Japan, nearly a fifth of adults have an outstanding

housing loan, but only half of them are financially literate and just 37 percent of them correctly

answer the compound interest question.

Source: S&P Global FINLIT Survey and Global Findex database.

Note: The height of the bar is the percentage of adults that have a housing loan.

Canada Germany JapanFrance Italy United

Kingdom

United States

20%

10%

30%

40%

0%

Financially

literate

Not

nancially

literate

FINANCIAL LITERACY AROUND THE WORLD | PAGE 21

3.

Conclusion

Worldwide, just 1-in-3 adults show an understanding of basic financial concepts.

Although financial literacy is higher among the wealthy, well educated, and those

who use financial services, it is clear that billions of people are unprepared to

deal with rapid changes in the financial landscape. Credit products, many of

which carry high interest rates and complex terms, are becoming more readily

available. Governments are pushing to increase financial inclusion by boosting

access to bank accounts and other financial services but, unless people have

the necessary financial skills, these opportunities can easily lead to high debt,

mortgage defaults, or insolvency. This is especially true for women, the poor,

and the less educated—all of whom suffer from low financial literacy and are

frequently the target of government programs to expand financial inclusion.

Financial literacy challenges confront developing economies and advanced

economies alike. In China, for example, credit card ownership has doubled

since 2011 to 16 percent (Demirguc-Kunt et al., 2015), yet only half of credit

card owners can perform simple calculations related to interest. Credit cards

are more established in the United States, where they are used by 60 percent of

adults. But there, too, understanding of related financial concepts is rather low:

just 57 percent of credit card owners correctly answer the interest question.

A retirement crisis looms in Europe as governments slash public pensions

and call on their citizens to take a bigger role in retirement planning. They are

not prepared. The continent is plagued by chronic under-saving for old age,

especially in the East, and older adults lack the financial skills needed to deal

with the economic challenges of retirement. The numbers in the EU as a whole

are hardly more encouraging: Just 47 percent of those who do not save for old

age show understanding of basic financial concepts.

Given these risks, policymakers should build strong consumer protection

regimes to safeguard citizens from financial abuse and provide a smooth market

environment. A research review by a team of World Bank experts found that

targeted financial literacy programs that are focused on specific behaviors

and populations can lead to smarter financial decisions (Miller et al., 2014).

Researchers have also found that financially savvy adults are, in general, less

likely to default on loans and more likely to save for retirement (Lusardi and

Mitchell, 2014). Because of this, policymakers should consider providing specific

financial literacy training to vulnerable groups, such as women, the poor, and

adults approaching retirement.

FINANCIAL LITERACY AROUND THE WORLD | PAGE 22

FINANCIAL LITERACY AROUND THE WORLD | PAGE 23

Financial Literacy: A Country-by-Country Breakdown

ECONOMY

ADULTS

WHO ARE

FINANCIALLY

LITERATE (%)

Afghanistan 14

Albania 14

Algeria 33

Angola 15

Argentina 28

Armenia 18

Australia 64

Austria 53

Azerbaijan 36

Bahrain 40

Bangladesh 19

Belarus 38

Belgium 55

Belize 33

Benin 37

Bhutan 54

Bolivia 24

Bosnia and Herzegovina 27

Botswana 52

Brazil 35

Bulgaria 35

Burkina Faso 33

Burundi 24

Cambodia 18

Cameroon 38

Canada 68

Chad 26

Chile 41

China 28

ECONOMY

ADULTS

WHO ARE

FINANCIALLY

LITERATE (%)

Colombia 32

Congo, Dem. Rep. 32

Congo, Rep. 31

Costa Rica 35

Croatia 44

Cyprus 35

Czech Republic 58

Côte d’Ivoire 35

Denmark 71

Dominican Republic 35

Ecuador 30

Egypt, Arab Rep. 27

El Salvador 21

Estonia 54

Ethiopia 32

Finland 63

France 52

Gabon 35

Georgia 30

Germany 66

Ghana 32

Greece 45

Guatemala 26

Guinea 30

Haiti 18

Honduras 23

Hong Kong SAR, China 43

Hungary 54

India 24

FINANCIAL LITERACY AROUND THE WORLD | PAGE 24

Financial Literacy: A Country-by-Country Breakdown

ECONOMY

ADULTS

WHO ARE

FINANCIALLY

LITERATE (%)

Indonesia 32

Iran, Islamic Rep. 20

Iraq 27

Ireland 55

Israel 68

Italy 37

Jamaica 33

Japan 43

Jordan 24

Kazakhstan 40

Kenya 38

Korea, Rep. 33

Kosovo 20

Kuwait 44

Kyrgyz Republic 19

Latvia 48

Lebanon 44

Lithuania 39

Luxembourg 53

Macedonia, FYR 21

Madagascar 38

Malawi 35

Malaysia 36

Mali 33

Malta 44

Mauritania 33

Mauritius 39

Mexico 32

Moldova 27

ECONOMY

ADULTS

WHO ARE

FINANCIALLY

LITERATE (%)

Mongolia 41

Montenegro 48

Myanmar 52

Namibia 27

Nepal 18

Netherlands 66

New Zealand 61

Nicaragua 20

Niger 31

Nigeria 26

Norway 71

Pakistan 26

Panama 27

Peru 28

Philippines 25

Poland 42

Portugal 26

Puerto Rico 32

Romania 22

Russian Fed. 38

Rwanda 26

Saudi Arabia 31

Senegal 40

Serbia 38

Sierra Leone 21

Singapore 59

Slovak Republic 48

Slovenia 44

Somalia 15

FINANCIAL LITERACY AROUND THE WORLD | PAGE 25

Financial Literacy: A Country-by-Country Breakdown

ECONOMY

ADULTS

WHO ARE

FINANCIALLY

LITERATE (%)

South Africa 42

Spain 49

Sri Lanka 35

Sudan 21

Sweden 71

Switzerland 57

Taiwan, China 37

Tajikistan 17

Tanzania 40

Thailand 27

Tog o 38

Tunisia 45

Turkey 24

Turkmenistan 41

Uganda 34

Ukraine 40

United Arab Emirates 38

United Kingdom 67

United States 57

Uruguay 45

Uzbekistan 21

Venezuela, RB 25

Vietnam 24

West Bank and Gaza 25

Yemen, Rep. 13

Zambia 40

Zimbabwe 41

FINANCIAL LITERACY AROUND THE WORLD | PAGE 26

Survey methodology

Surveys are conducted face-to-face in economies where telephone coverage

represents less than 80 percent of the population or is the customary

methodology. In most economies the fieldwork is completed in two to four

weeks. In economies where face-to-face surveys are conducted, the first stage of

sampling is the identification of primary sampling units. These units are stratified

by population size, geography, or both, and clustering is achieved through one

or more stages of sampling. Where population information is available, sample

selection is based on probabilities proportional to population size. Otherwise,

simple random sampling is used. Random route procedures are used to select

sampled households. Unless an outright refusal occurs, interviewers make up to

three attempts to survey the sampled household. To increase the probability of

contact and completion, attempts are made at different times of the day and,

where possible, on different days. If an interview cannot be obtained at the

initial sampled household, a simple substitution method is used. Respondents

are randomly selected within the selected households by means of the Kish grid.

In economies where cultural restrictions dictate gender matching, respondents

are randomly selected through the Kish grid from among all eligible adults of the

interviewer’s gender.

In economies where telephone interviewing is employed, random digit dialing

or a nationally representative list of phone numbers is used. In most economies

where cell phone penetration is high, a dual sampling frame is used. Random

selection of respondents is achieved by using either the latest birthday or

Kish grid method. At least three attempts are made to reach a person in each

household, spread over different days and times of day.

Data weighting is used to ensure a nationally representative sample for

each economy. Final weights consist of the base sampling weight, which

corrects for unequal probability of selection based on household size, and the

poststratification weight, which corrects for sampling and nonresponse error.

Poststratification weights use economy-level population statistics on gender

and age and, where reliable data are available, education or socioeconomic

status. More information on the data collection period, number of interviews,

approximate design effect, and margin of error, as well as sampling details for

each economy, can be found in Demirguc-Kunt et al. (2015).

FINANCIAL LITERACY AROUND THE WORLD | PAGE 27

References

Abreu, Margarida, and Victor Mendes, (2010). “Financial Literacy and Portfolio

Diversification,” Quantitative Finance, Vol. 10(5), pp. 515-528.

Allen, Franklin, Asli Demirguc-Kunt, Leora Klapper, and Maria Soledad

Martinez Peria, (2012). “The Foundations of Financial Inclusion: Understanding

Ownership and Use of Formal Accounts,” World Bank Policy Research Working

Paper 6290.

Behrman, Jere R., Olivia S. Mitchell, Cindy K. Soo, and David Bravo, (2012).

“The Effects of Financial Education and Financial Literacy: How Financial

Literacy Affects Household Wealth Accumulation,” American Economic Review:

Papers &Proceedings, Vol. 102(3), pp. 300-304.

Demirguc-Kunt, Asli, Leora Klapper, Dorothe Singer, and Peter Van Oudheusden,

(2015). “The Global Findex Database 2014: Measuring Financial Inclusion

around the World,” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 7255.

Global Findex, 2014. http://www.worldbank.org/globalfindex

Hanke, Steve H., and Nicholas E. Krus, (2013). “World Hyperinflations,” in

Routledge Handbook of Major Events in Economic History, pp. 367-377, edited by

Randall E. Parker and Robert Whaples, New York: Routledge Taylor and Francis

Group, 2013.

Klapper, Leora, and Dorothe Singer, (2014). “The Opportunities of Digitizing

Payments,” World Bank, Washington, DC.

Lusardi, Annamaria, and Carlo de Bassa Scheresberg, (2013). “Financial Literacy

and High-Cost Borrowing in the United States,” NBER Working Paper 18969.

Lusardi, Annamaria, and Olivia S. Mitchell, (2014). “The Economic Importance

of Financial Literacy: Theory and Evidence,” Journal of Economic Literature,

American Economic Association, Vol. 52(1), pages 5-44, March.

Lusardi, Annamaria, and Peter Tufano, (2015). “Debt Literacy, Financial

Experiences, and Over Indebtedness,” Journal of Pension Economics and Finance,

Vol. 14, special issue 4, pp. 332-328, October.

Miller, Margaret, Julia Reichelstein, Christian Salas, and Bilal Zia, (2014). “Can

You Help Someone Become Financially Capable? A Meta-Analysis of the

Literature,” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 6745.

OECD, (2014). “PISA 2012 Results in Focus: What 15-year-olds know and what

they can do with what they know,” OECD, Paris.

Stango, Victor, and Jonathan Zinman, (2009). “Exponential Growth Bias

and Household Finance,” The Journal of Finance, Vol. 64(6), pp. 2807-2849,

December.

HTTP://WWW.FINLIT.MHFI.COM