A Changing

Landscape:

Trends in official financial

flows and the aid architecture

November 2021

November 2021

For discussion at the ODI workshop on

November 4, 2021

World Bank Group

Development Finance

i

LIST OF FIGURES AND TABLES................................................................................... II

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ..........................................................................III

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ................................................................................................ IV

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................ V

I. INTRODUCTION .........................................................................................................1

II. PUBLIC SECTOR FINANCING IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES ...........................5

III. TRENDS IN OFFICIAL FINANCIAL FLOWS ...........................................................9

III.A Distribution of Official Financial Flows ..............................................................9

III.A.1 Distribution of Official Flows by Country Income Group ....................................................10

III.A.2 Sectoral Distribution of Official Finance ...............................................................................12

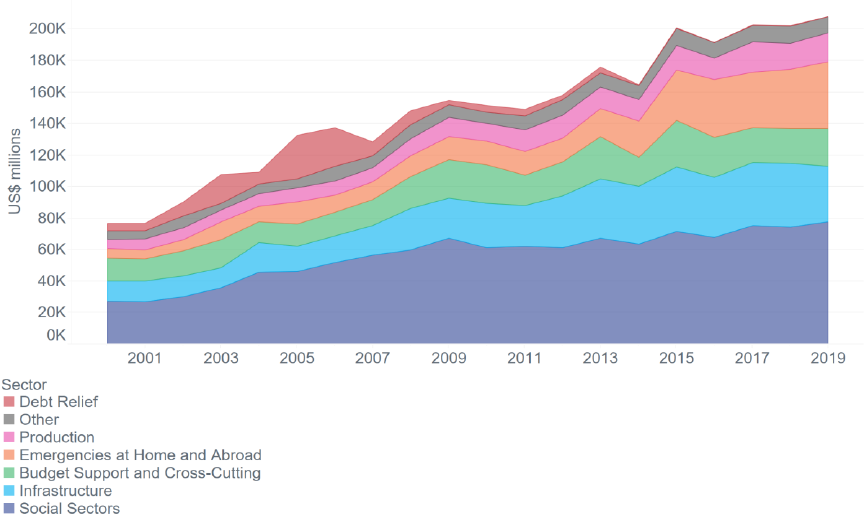

III.A.3 Geographical Distribution of Official Finance ......................................................................16

III.B Overall Trends in Official Development Assistance .........................................18

III.B.1 Main Trends ...........................................................................................................................18

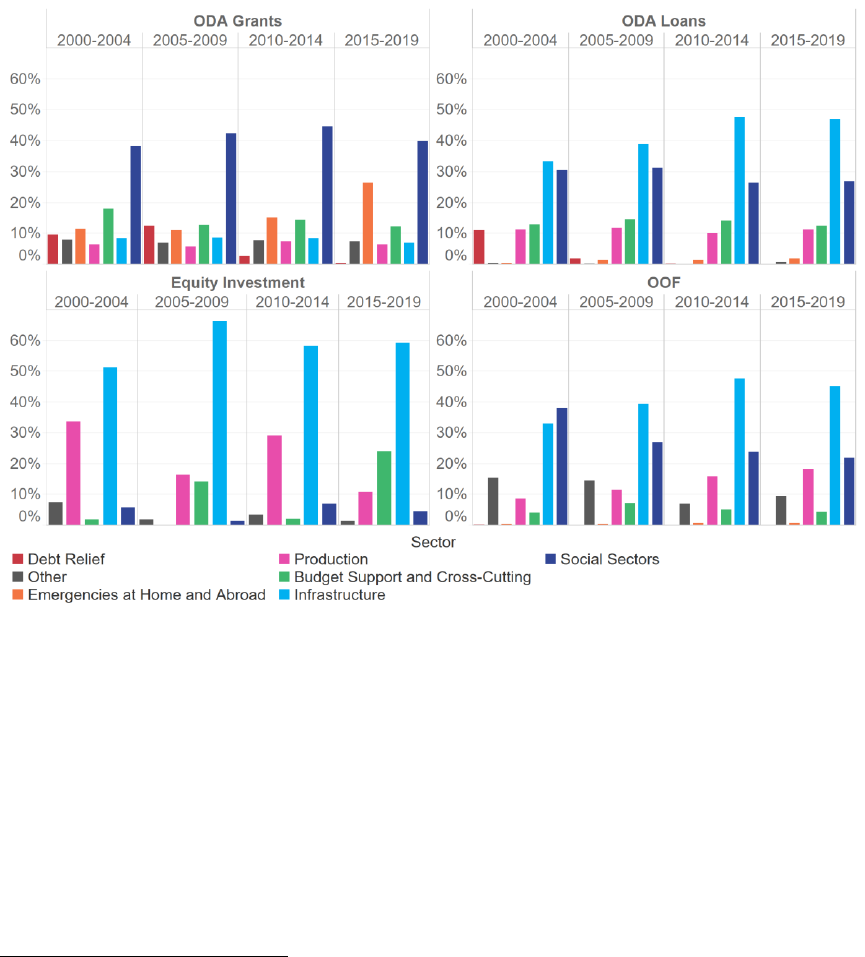

III.B.2 Country Programmable Aid ...................................................................................................20

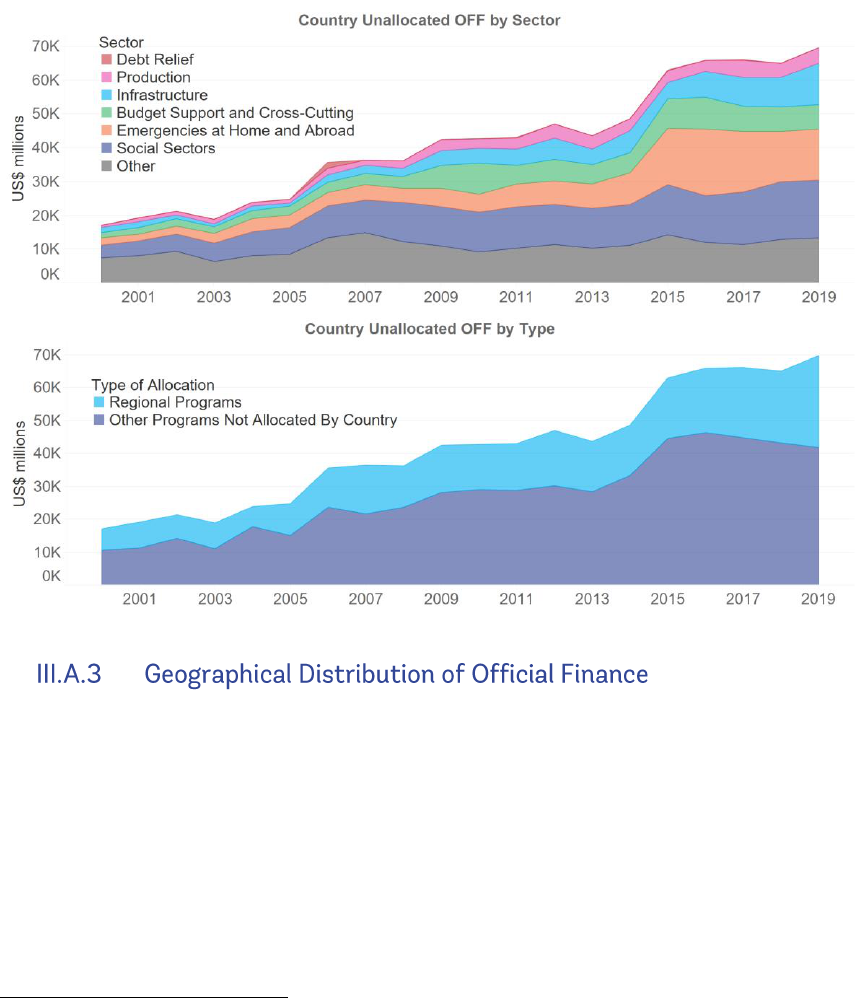

III.B.3 Bilateral vs. Multilateral ODA...............................................................................................22

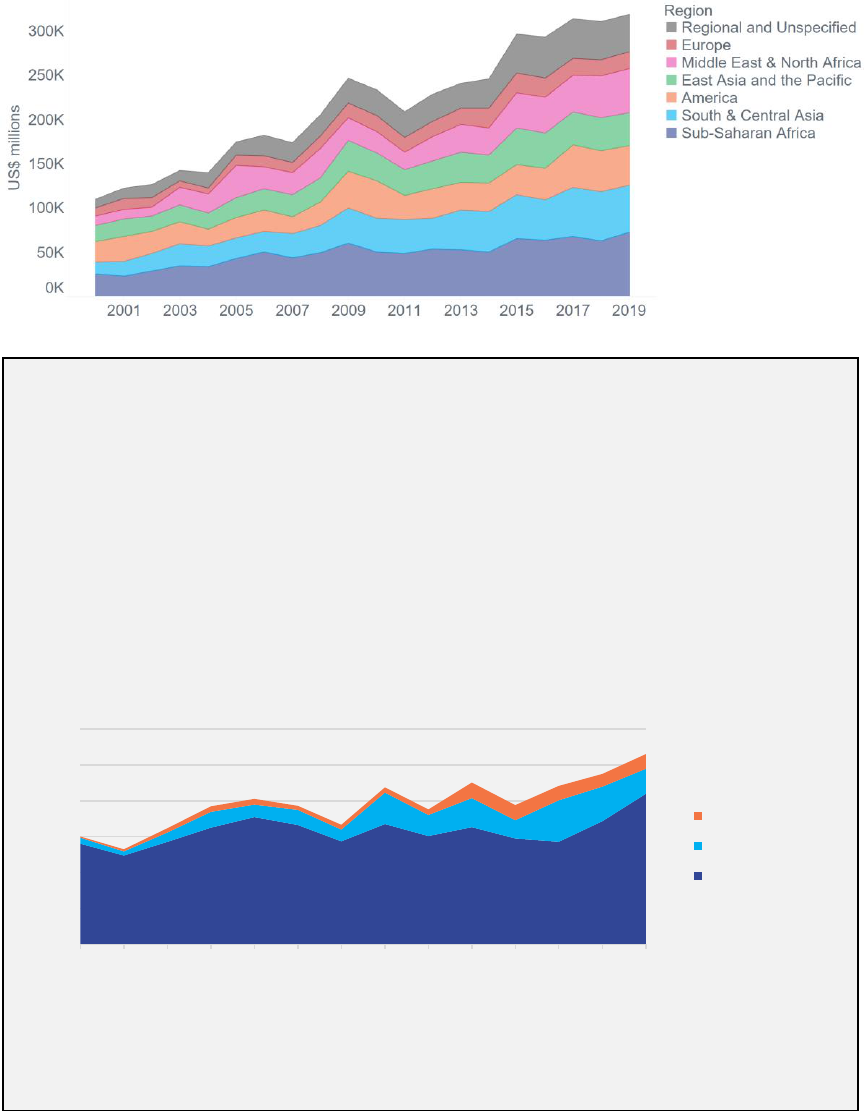

III.B.4 Official Flows to IDA-Eligible Countries..............................................................................24

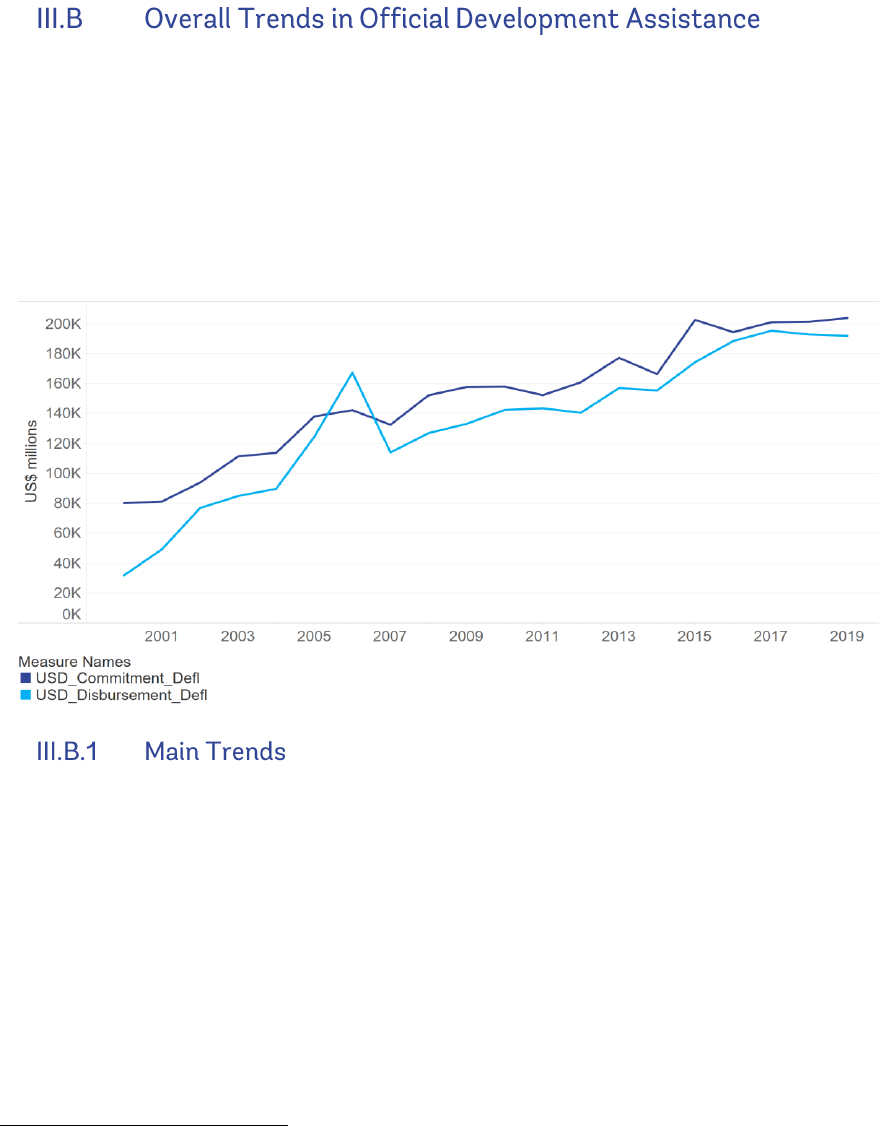

IV. PROLIFERATION AND FRAGMENTATION .........................................................26

IV.A Proliferation of Official Financial Channels ......................................................26

IV.B Fragmentation of Official Finance .....................................................................29

V. SUMMARY OF FINDINGS AND AREAS FOR FURTHER ANALYSIS...............32

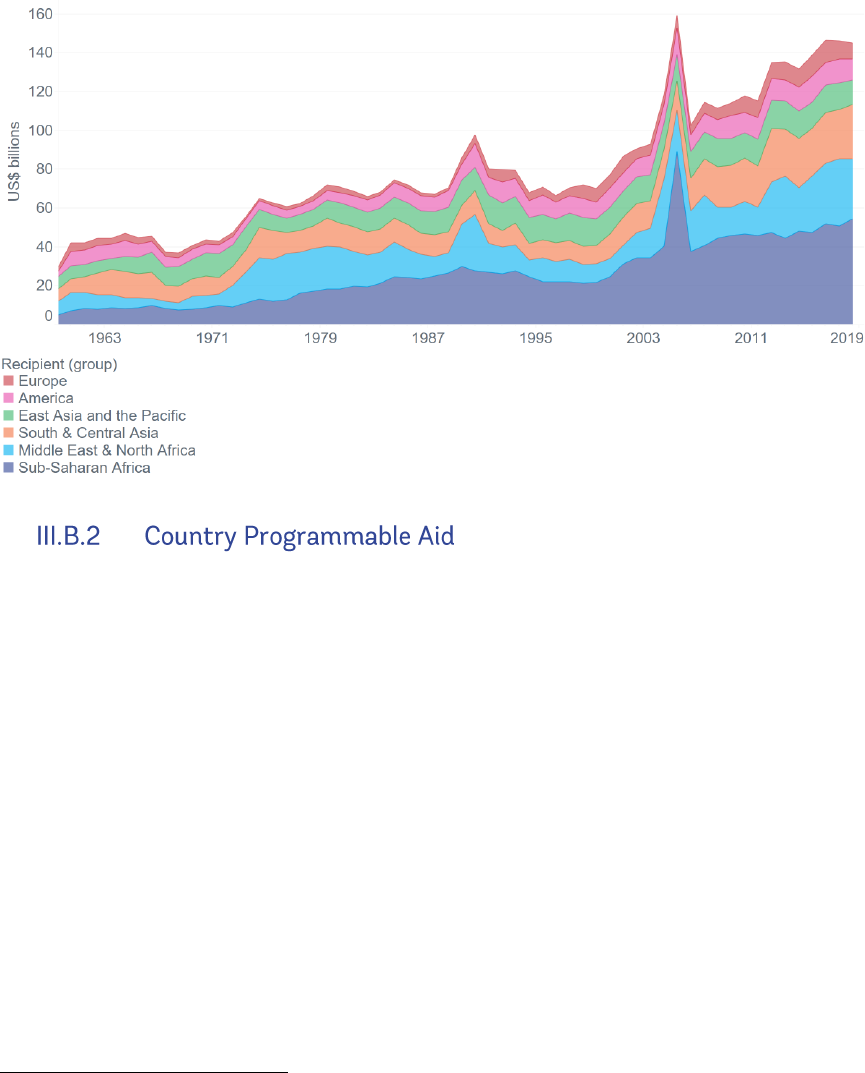

V.A Summary of Findings .........................................................................................32

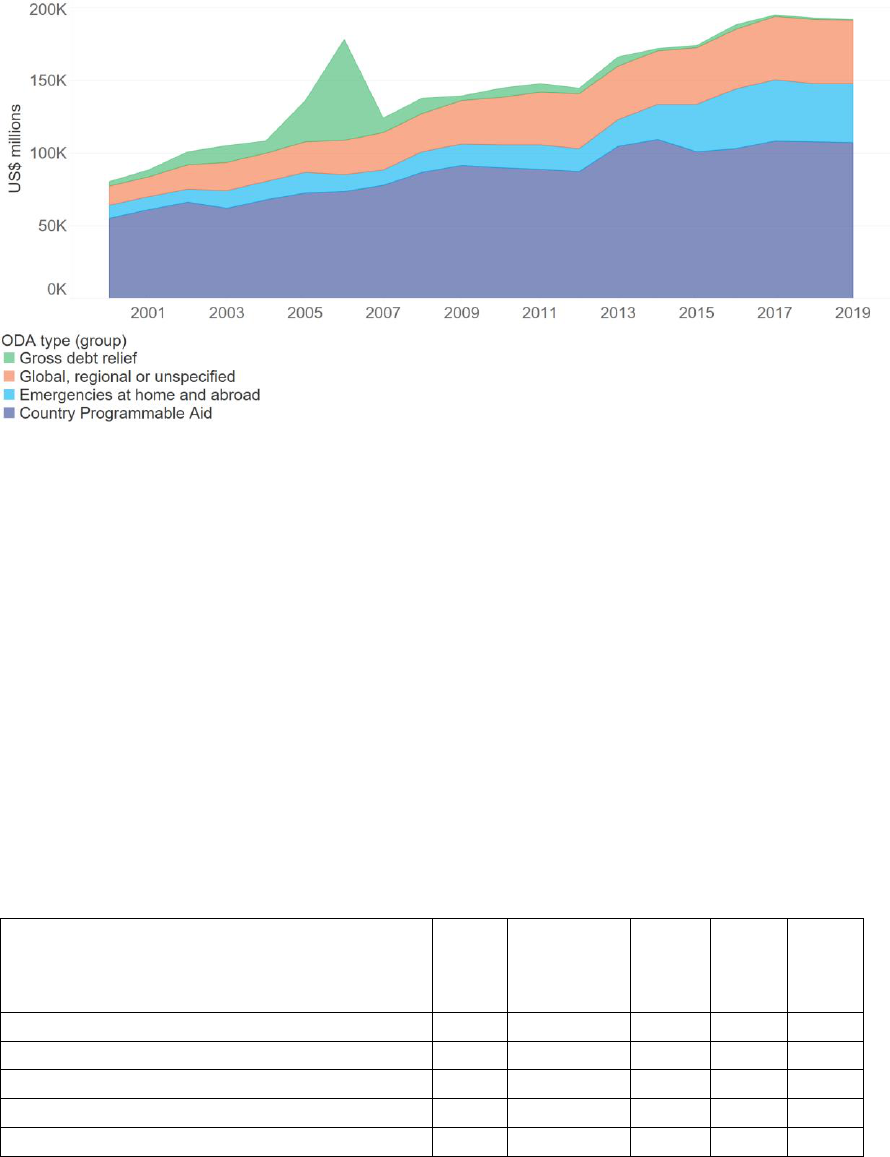

V.B Areas for Further Analysis .................................................................................33

REFERENCES ..................................................................................................................35

ANNEX..............................................................................................................................36

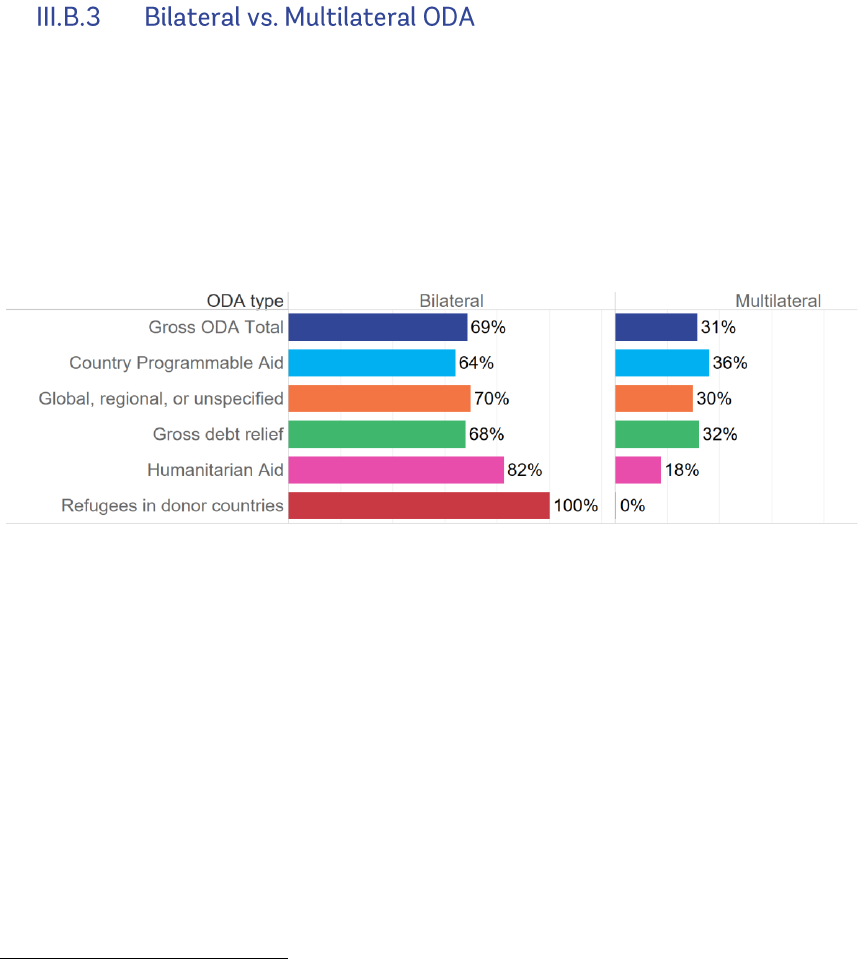

ii

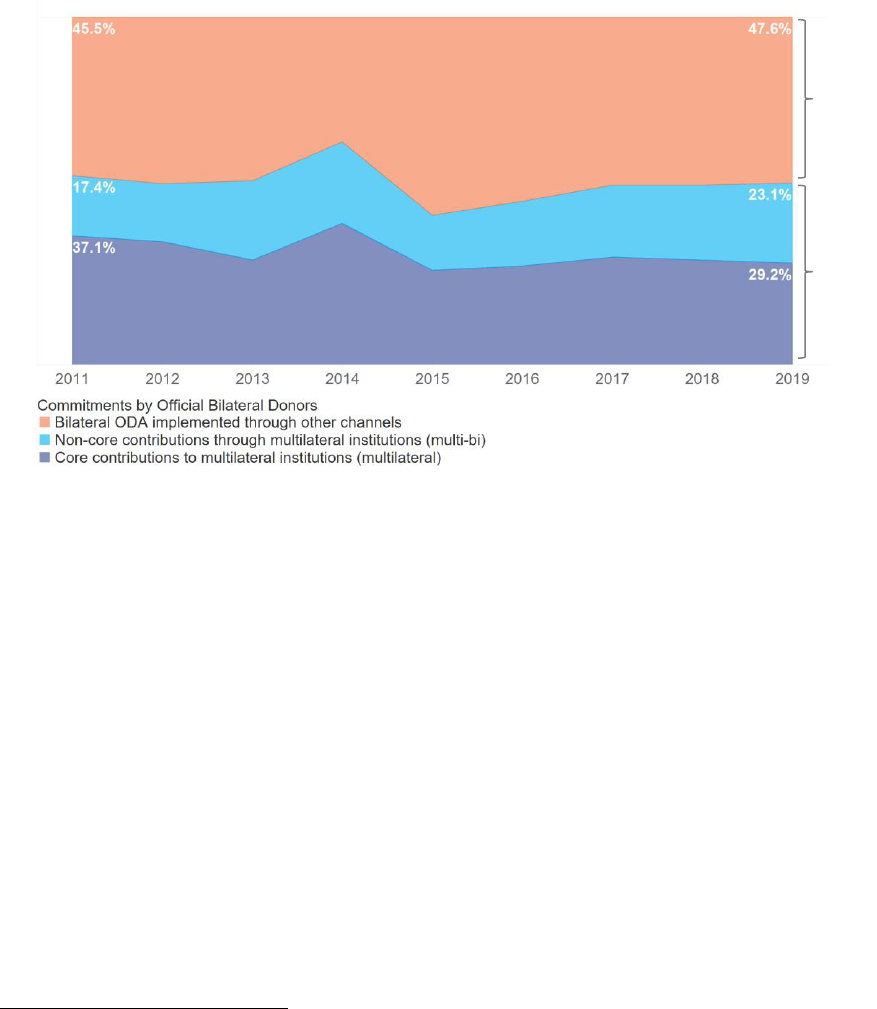

Figure 1: Official Financial Flows to Developing Countries.............................................. 2

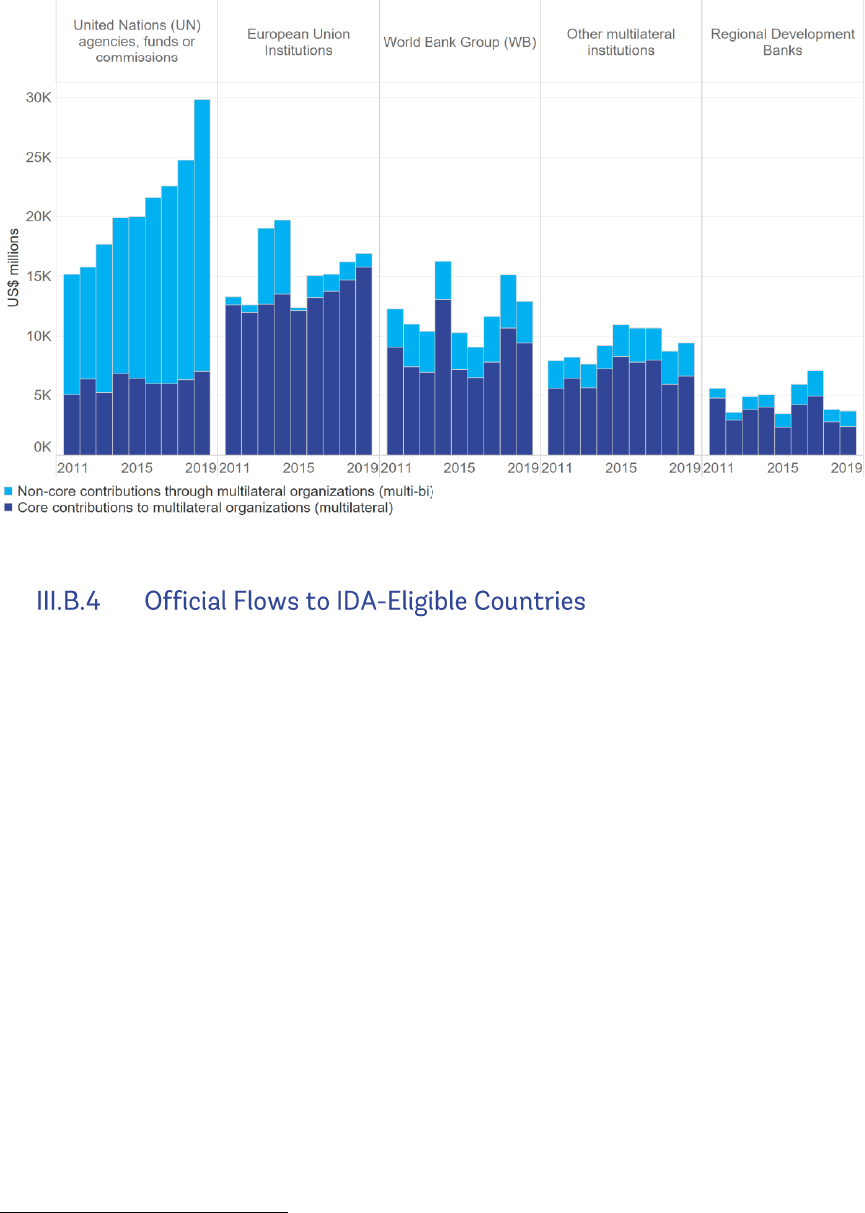

Figure 2: Total External Financing to the Public Sector in Developing Countries ............ 5

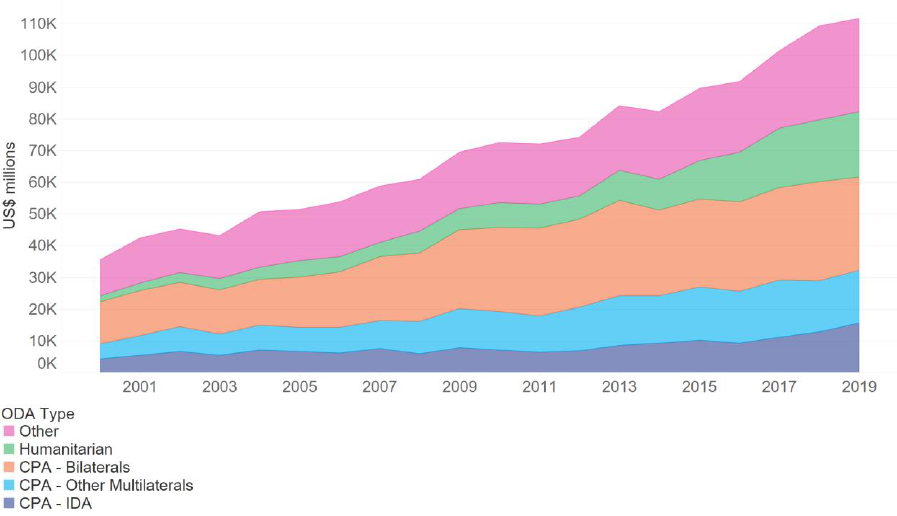

Figure 3: Official Finance to Developing Countries........................................................... 6

Figure 4: Official Loan Commitments to Developing Countries ....................................... 7

Figure 5: BRICS Loan Commitments by Recipient Country ............................................. 8

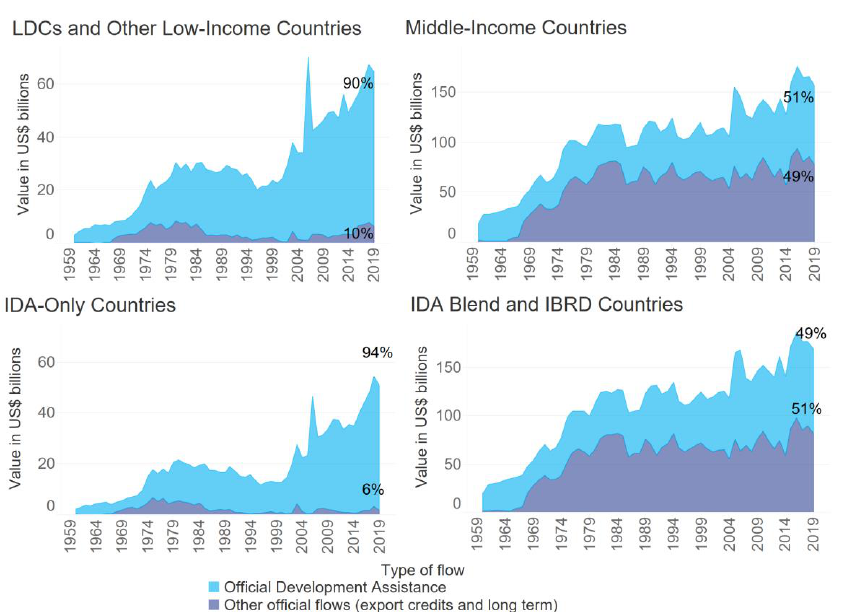

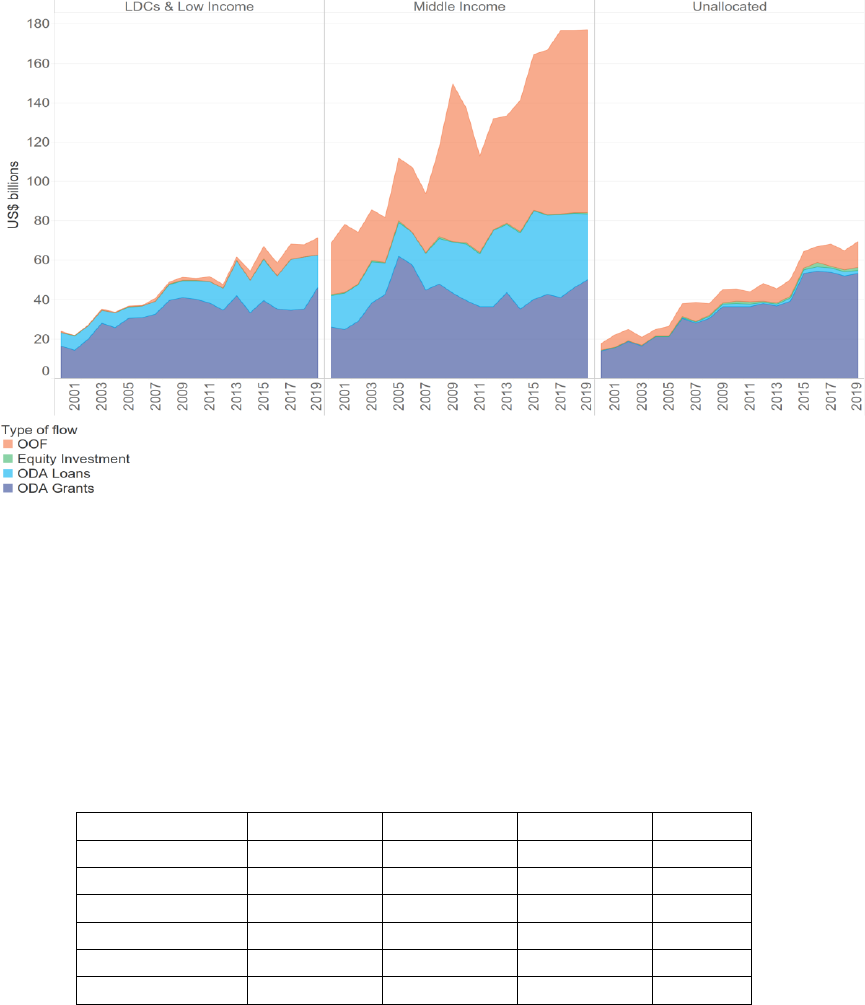

Figure 6: Evolution of Official Financial Flows by Country Income Group ................... 11

Figure 7: Sectoral Distribution of Official Financial Flows ............................................. 12

Figure 8: Sectoral Distribution of Official Flows by Income Group ................................ 13

Figure 9: Sectoral Distribution by Type of Flows ............................................................ 14

Figure 10: Distribution of OFF Unallocated to Specific Recipient Countries .................. 16

Figure 11: Official Financial Flows by Regions ............................................................... 17

Figure 12: ODA Commitments and Disbursements since 2000 ....................................... 18

Figure 13: ODA Commitments by Sector ........................................................................ 19

Figure 14: Gross Official Development Assistance by Region ........................................ 20

Figure 15: Evolution of ODA by Type ............................................................................. 21

Figure 16: Distribution of Bilateral and Multilateral ODA by Type ................................ 22

Figure 17: Implementation Channels for Bilateral ODA .................................................. 23

Figure 18: ODA to and through Major International Organizations ................................ 24

Figure 19: Gross ODA Disbursements to IDA-eligible Countries by Type and Source .. 25

Figure 20: Proliferation of Official Financial Providers and Entities ............................... 27

Figure 21: Distribution of Official Finance by Implementation Channel ......................... 28

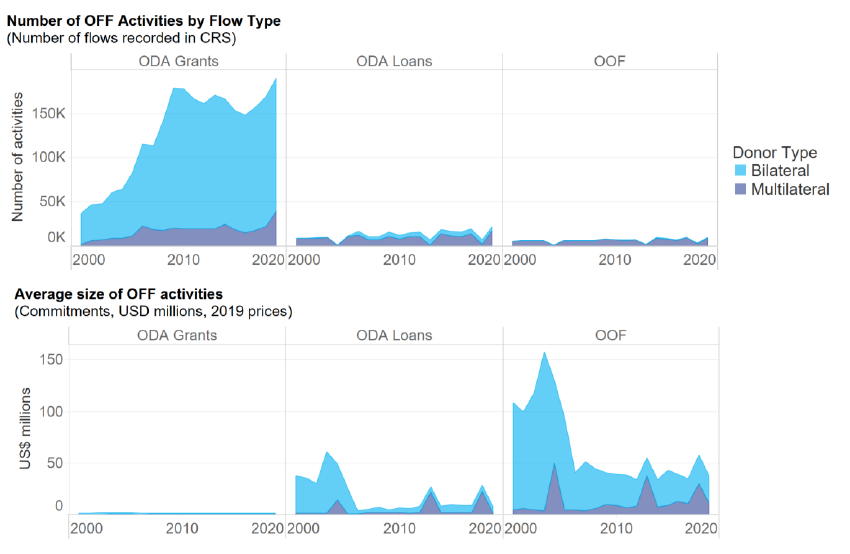

Figure 22: Number of Official Finance Activities by Sector ............................................ 29

Figure 23: Number and Size of Official Finance Activities by Aid Type ........................ 30

Table 1: Official Financial Flows to Developing Countries by Type of Flow ................. 10

Table 2: Official Financial Flows by Income Group ........................................................ 10

Table 3: Distribution of Official Flows by Country Income Group ................................. 11

Table 4: Growth in ODA categories between 2000 and 2019 .......................................... 21

Table 5: Official Finance Providers by Number of Entities ............................................. 27

Table 6: Number and Average Size of Donor Funded Activities ..................................... 31

iii

BRICS

Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa

CAGR

Compound Annual Growth Rate

CPA

Country Programmable Aid

CRS

Creditor Reporting System

DAC

Development Assistance Committee

DRS

Debtor Reporting System

DSA

Debt Sustainability Analysis

EBRD

European Bank for Reconstruction and Development

FCS

Fragile and Conflict-affected Situations

FIF

Financial Intermediary Fund

IBRD

International Bank for Reconstruction and Development

IDA

International Development Association

IDB

Inter-American Development Bank

IMF

International Monetary Fund

LDC

Least Developed Country

LIC

Low-Income Country

MDB

Multilateral Development Bank

MIC

Middle-Income Country

NGO

Non-Governmental Organization

ODA

Official Development Assistance

OFF

Official Financial Flows

OOF

Other Official Flows

OECD

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

TA

Technical Assistance

TOSSD

Total Official Support for Sustainable Development

UN

United Nations

iv

This paper was prepared by Gaiv Tata (External Consultant, Principal Author), Stefano

Migliorisi (External Consultant), Guillaume Kroll (Strategy Officer, DFCII), Arvind Balaji

Rajasekaran (Research Analyst, DFCII), Deborah Oppong-Asumang (Consultant, DFCII),

and Natalia Antsilevich (Senior Operations Officer, DFCII). It benefited greatly from

consultations with the OECD (Olivier Cattaneo) both at concept stage and in the

interpretation of findings. Overall guidance was provided by Akihiko Nishio (Vice

President, DFI), Samuel Maimbo (Director, DFCII), Dirk Reinermann (Director, DFTPR),

Enrique Blanco Armas (Manager, DFCII), Clara de Sousa (former Manager, DFCII), and

Abha Prasad (Lead Economist, DFCII). Other helpful inputs were received from Haishan

Fu (Director, DECDG), Evis Rucaj (Senior Economist, DECES), Rubena Sukaj

(Economist, DECES), Ferdinand Vinuya (Senior Operations Officer, DFCII), Anton

Dobronogov (former Senior Economist, DFCII), Angelique DePlaa (Adviser, DFIVP),

Priya Basu (former Adviser, DFIVP), Irina Gabrial (Senior Operations Officer, DFIVP),

Brice Quesnel (Manager, DFTPR), Mei Leng Chang (Manager, Financial Management,

DFTPR), Ashish Makkar (Senior Finance Officer, DFTPR), Michelle Yan Li (Financial

Officer, DFTPR), Long Hanhua Wang (Junior Professional Officer, DFTPR), Patricia da

Camara (Senior External Affairs Officer, ECRMI), Ayhan Kose (Director, EPGDR), and

Ighodaro Omoigui (Senior Operations Officer, MDOPS). The support of Ad'm DiBiaso

(External Consultant) in cover design is gratefully acknowledged.

v

1. This report updates the World Bank’s analysis of the global aid architecture,

which had previously been provided in three reports between 2007 and 2011. It

broadens the focus from Official Development Assistance (ODA) to all public and private

sector financing to developing countries. It does so by complementing for the first time

data reported by official donors to the OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC)

and Creditor Reporting System (CRS) with data reported by recipient governments to the

World Bank Debtor Reporting System (DRS). Despite some methodological limitations,

this approach helps to shed light on financial flows from the private sector as well as

sovereign donors which do not report consistently to the OECD DAC.

2. The main objective of the paper is to provide an impartial quantitative overview

of changes in the global aid architecture landscape, particularly over the last decade,

with a focus on changes in volumes of financing, sources of financing, and delivery

mechanisms. The paper covers financial flows up to the end of calendar year 2019, the

limit covered by most public databases at the time of publication unless otherwise

indicated. It can thus provide a useful baseline for future assessments of the impact of

COVID-19 on development finance. Another objective of this paper is to serve as

groundwork for more detailed and qualitative analysis of emerging issues in the global aid

architecture, such as the proliferation of donor entities and fragmentation of aid flows, the

rising volume of aid offered beyond the country level, and the concessionality of aid.

Follow-up papers on these topics would, wherever relevant, discuss policy implications for

the global aid community or the World Bank.

3. The main findings of the report can be summarized as follows:

• Financial flows to developing countries have grown steadily over the last

decade, largely thanks to private sector finance. During this period, private

finance grew by 10 percent a year while official (i.e., public) finance grew by 2

percent a year. While in 2010 public finance represented 64 percent of total financial

flows to developing countries, by 2019 public and private flows were almost equal.

• Among public lenders, BRICS countries provided significant volumes of loan

financing. Over the last ten years, the BRICS provided 22 percent of loan financing

globally. At the donor level, the World Bank Group and China were the two largest

individual sources of loan financing. While the World Bank Group also provides a

significant amount of grant financing, there is no data source which adequately

covers grants provided by BRICS countries.

• Middle-Income Countries (MICs) received almost half of total ODA

commitments since 2000 and 85 percent of Other Official Flows (OOF). Least

Developed and Low-Income Countries (LDCs/LICs) received 94 percent of their

financing as ODA. However, this amount only represented 30 percent of total ODA

commitments over the period.

vi

• The volume of funding which donors have not identified as allocated to specific

recipient countries almost quadrupled over the past two decades and now

constitutes more than a fifth of official finance to developing countries. The

rising share of resources not assigned to specific recipients indicates a growing focus

on global and regional public goods and on support for emergencies (humanitarian

aid and support to refugees in donor countries).

• Aid concessionality varied significantly across sectors, with grants deployed

mostly for social sectors and support for emergencies, and concessional and

non-concessional loans favored for infrastructure. More than two thirds of ODA

grant commitments in the past five years were made in the social sectors and in

support for emergencies. In contrast, 44 and 43 percent of ODA loans and OOF,

respectively, were used for infrastructure investments.

• There was a modest growth in the number of official finance providers since

2000, but a 2.5x growth in the number of entities providing official finance.

Between 2000 and 2019, the number of official finance providers around the world

grew from 47 to 70 while the number of entities providing official finance expanded

from 191 to 502. The rapid increase in the latter may be due partly to the lack of full

reporting at the beginning of the period.

• Development activities remain highly fragmented; the average size of official

finance activities has decreased by approximately one third in value in twenty

years. Fragmentation appears to be mostly concentrated in social sectors and in

bilateral activities. The impact on ODA grants, the dominant type of official flows,

was particularly strong. The average size of an ODA grant decreased from US$1.5

million in 2000 to US$0.8 million today.

4. Findings from this report would benefit from additional analysis in three key areas:

• Aid Effectiveness. Considering the limited systematic evidence regarding the

impact of proliferation and fragmentation on aid effectiveness and efficiency,

additional research could be undertaken to identify discernable patterns between

findings from aid quality surveys and the quantitative information on proliferation

and fragmentation made available in this report.

• Aid Beyond the Country Level. Given the growing amount of funding unallocated

to specific recipient countries, its three main components (i.e., emergencies at home

and abroad, regional programs, and global public goods) could be further analyzed.

• Evolution of Concessionality. A more detailed analysis of concessionality of

official flows could be useful from various perspectives, including the transition

from grant financing to concessional loan financing in selected LDCs/LICs, the

continued significant deployment of both grants and concessional loans in selected

MICs (particularly those with market access), and the link between changes in terms

of financial assistance from the World Bank and the terms offered by other financial

providers.

vii

Box 1: Key Data Sources and Terminology Used

Data Sources

The analysis in this paper utilizes two OECD databases which both contain data reported by donor

countries and multilateral agencies. The Development Assistance Committee (DAC) database contains

aggregated data along three dimensions: donor; donor by recipient country; and donor by sector. The

Creditor Reporting System (CRS) database provides disaggregated transaction-by-transaction data.

In Section II of this paper, the World Bank’s Debtor Reporting System (DRS) database is also utilized

to complement the OECD datasets. DRS data includes official loans (i.e., bilateral and multilateral loan

commitments) as well as flows from private financiers, as reported by recipient countries themselves.

Terminology Used

Types of Donors:

• Bilateral donors include individual governments and their development agencies.

• Bilateral flows can either be directly distributed from donor countries to recipient countries, or to

multilateral organizations with donor-imposed restrictions on their use (i.e., earmarked for a

specific sector, theme, country, or region, also referred to as non-core or multi-bi flows).

• Multilateral donors include international institutions with governmental membership which

conduct all or a significant part of their activities in favor of development and aid recipient

countries. They include multilateral development banks (e.g., World Bank, regional development

banks), United Nations agencies, as well as multinational groupings (e.g., certain European Union

and Arab agencies).

• Contributions by bilateral donors to multilateral donors are considered multilateral flows if they

are pooled with other contributions and disbursed at the discretion of the agency (i.e., without any

use of restrictions or non-earmarked, also referred to as core flows).

Types of Flows:

• Official Financial Flows (OFF) consist of Official Development Assistance and Other Official

Flows.

• Official Development Assistance (ODA) consists of resource flows (grants, loans and equity) to

countries and territories on the DAC List of ODA Recipients (developing countries) and to

multilateral agencies which are: (a) undertaken by the official sector; (b) with promotion of

economic development and welfare as the main objective; and (c) at concessional financial terms.

Until 2018, loans were concessional if their Grant Element was at least 25 percent (calculated at a

10 percent discount rate of 10 percent). Since 2019, both grant element and discount rate vary

based on the Income Group of the recipient country.

i

In addition to financial flows, Technical Co-

operation is included in ODA. Equity provided by the official sector excludes Foreign Direct

Investment, which is included under private flows.

• Other Official Flows (OOF) consist of transactions by the official sector with countries on the

DAC List of ODA Recipients which do not meet the conditions for eligibility as ODA, either

because they are not primarily aimed at development, or because they have less than the required

grant element.

• Private Flows consist of flows at market terms financed out of external private sector resources

(i.e., changes in holdings of private long-term assets held by residents of the reporting country)

and private grants (i.e., grants by non-governmental organizations and other private bodies, net of

subsidies received from the official sector).

i

See http://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-

standards/modernisation-dac-statistical-system.htm

viii

Terminology Used (Continued)

Commitments vs. Disbursements:

• Commitments are firm obligations, expressed in writing and backed by the necessary funds,

undertaken by an official donor to provide specified assistance to a recipient country or a

multilateral organization. Bilateral commitments are recorded in the full amount of expected

transfer, irrespective of the time required for the completion of disbursements. Commitments to

multilateral organizations are reported as the sum of (i) any disbursements in the year reported on

which have not previously been notified as commitments and (ii) expected disbursements in the

following year.

• Disbursements correspond to the release of funds to or the purchase of goods or services for, a

recipient (i.e., the amount thus spent). Disbursements record the actual international transfer of

financial resources, or of goods or services valued at the cost to the donor. Disbursements may be

recorded gross (the total amount disbursed over a given accounting period) or net (the gross

amount less any repayments of loan principal or recoveries on grants received during the same

period). It can take several years to disburse a commitment.

Classifications:

• Country Income Groups: ODA eligible countries are classified into two groups i.e., Least

Developed Countries and Low-Income Countries (LDCs and LICs) and Middle-Income Countries

(MICs).

ii

• Country eligibility for IBRD and/or IDA: Economies are divided into IDA, IBRD, and Blend

countries based on the operational policies of the World Bank. International Development

Association (IDA) countries are those with low per capita incomes that lack the financial ability

to borrow from the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD). Blend

countries are eligible for IDA loans but are also eligible for IBRD loans because they are deemed

to be financially creditworthy.

• Sector Classifications: Consists of social infrastructure and services, economic infrastructure and

services, production sectors, multi-sector and cross-cutting, commodity aid/general program

assistance, actions related to debt, humanitarian assistance, donor administrative costs, costs of

refugees in donor countries and unallocated. For purposes of analysis, a category entitled

‘emergencies at home and abroad’ was created combining humanitarian assistance and costs of

refugees in donor countries.

• Sector Allocable ODA: ODA flows aimed at fostering a particular sector in the recipient country.

Excludes contributions that are not allocable by sector (e.g., balance-of-payments support, actions

relating to debt, emergency assistance, administrative costs of donors, support to NGOs and

unallocated/unspecified ODA).

ii

https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-

standards/DAC_List_ODA_Recipients2018to2020_flows_En.pdf

1

1. This paper provides updated data and analysis on the structure and dynamics of

the global aid architecture. It reviews broad trends in overall financing for development and

within that, the role of Official Financial Flows (OFF) and more specifically, Official

Development Assistance (ODA). The paper analyzes the rising importance of non-

concessional financing, the continuing complexity of the global aid architecture, and other

phenomena with potential impact on aid effectiveness. The main objective of the paper is to

provide an impartial quantitative overview of changes in the aid architecture landscape,

particularly over the last decade (through the end of calendar year 2019), with a focus on

volumes of financing, sources of financing, and delivery mechanisms. Considering the period

covered, the paper provides a useful baseline for future assessments of the impact of COVID-

19 on development finance, which recent publications from the UN and the OECD have

already started to investigate.

1

Another objective of the paper is to provide the basis for more

detailed and qualitative analysis of emerging issues, such as aid concessionality, aid

proliferation and fragmentation, and aid beyond the country level. Follow-up papers on these

topics would, wherever relevant, discuss policy implications for the global aid community or

the World Bank.

2. The paper builds on prior aid architecture reports published by the World Bank.

The first Aid Architecture report

2

was prepared in the context of the IDA15 replenishment

negotiations, and later updated in May 2008

3

for the Third High Level Forum in Accra. The

two reports underscored the complexity of the global aid architecture, particularly the

proliferation of aid agencies on the supply side (with the average number of donors per

recipient country rising from about 12 in the 1960s to about 33 during the 2000s) and the

fragmentation of aid on the user side, both contributing to increased transaction costs at the

country level. The reports also discussed the prospects and challenges facing the donor

community in the perspective of ensuring the effectiveness of aid. A comprehensive update

4

was prepared in 2011 ahead of the Fourth High Level Forum in Busan; reporting on changes

in net financing flows to developing countries before and after the 2008 Global Financial

Crisis.

3. Aid architecture refers to the set of rules and institutions governing aid flows to

developing countries. Systematic measurement of aid has been undertaken over the last 60

years since the establishment of the Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development

(OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC) in 1961.

5

Since then, the OECD DAC

has served as the main forum for securing agreements on key definitions and changes thereto

(see Box 1). However, the global aid architecture has evolved without a pre-defined blueprint,

with most of today’s aid principles and institutions resulting from over half a century of debate

and joint decision-making. Broadly speaking, two aid “architectures” can be distinguished: the

1

See United Nations Inter-agency Task Force on Financing for Development, 2021 and OECD, 2021.

2

World Bank, 2007.

3

World Bank, 2008.

4

World Bank, 2011.

5

The committee of the OECD which deals with development co-operation matters. The DAC currently has

30 members. More info: https://www.oecd.org/dac/development-assistance-committee/.

2

“Cold War Architecture”, which lasted from the end of World War II to the fall of the Berlin

Wall in 1989; and the “Post Cold War Aid Architecture”, which started in 1990 and is still

evolving in important respects, such as through the global consensus around the Sustainable

Development Goals or through the increasing role of non-DAC donors.

6

4. This report seeks to go beyond Official Development Assistance (ODA) – the focus

of previous Aid Architecture reports – by adding to the analysis other flows that may not

meet ODA eligibility criteria. As a first step, Official Financial Flows (OFF), which include

both ODA and Other Official Flows (OOF) reported to the OECD DAC, were examined.

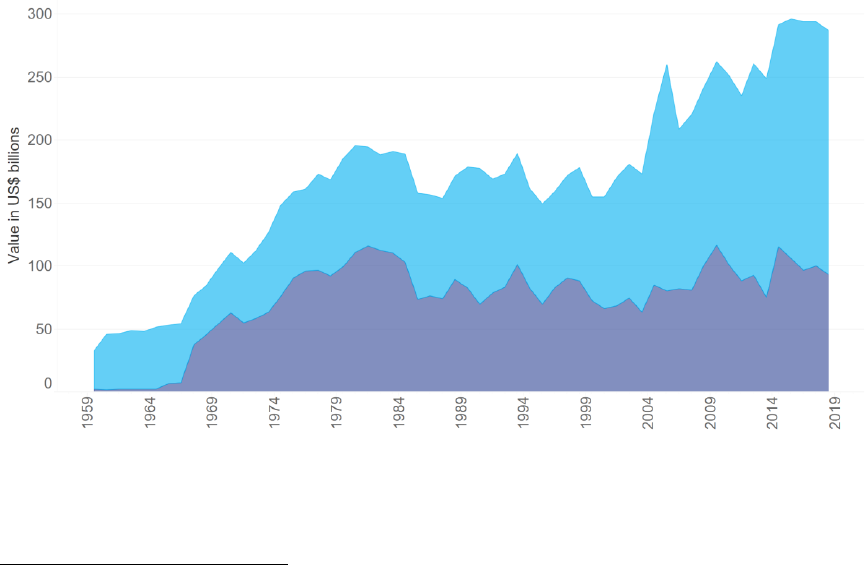

Overall, OFF increased substantially over the past 60 years, with an almost tenfold increase

between today and 1960. Within OFF, the share of non-ODA flows (i.e., OOF) varied

significantly over that period. From a mere 7 percent in 1960, it increased to an all-time high

of 60 percent in the beginning of the 1980s, before moderating to just above 30 percent in the

last few years (Figure 1). As expected, OOF constitute a higher portion of OFF in Middle-

Income Countries (MICs) and IBRD and IDA Blend countries than in Least Developed and

Low-Income Countries (LDCs/LICs) and IDA-only countries. In the first group, OOF now

constitutes approximately half of the official financing received, while it constitutes only 6 to

10 percent in the second. However, one notable limitation of this approach is that it only

captures transactions from donors who report to the OECD, thereby excluding flows from a

number of important bilateral providers, such as China or India, as well as from most private

financiers.

Figure 1: Official Financial Flows to Developing Countries

(Gross disbursements, US$ billions, 2019 prices)

6

See Annex 1 of the first Aid Architecture paper for a comprehensive review of the historical evolution of

the international aid architecture over the last half century. For more information on DAC membership, please

see: https://www.oecd.org/dac/development-assistance-committee/.

3

Source: OECD DAC Tables 2a and 2b

5. To draw a more comprehensive picture of all financial flows to developing

countries, this paper proposes to incorporate lending data from financial providers that

are not reporting consistently to the OECD DAC. For the first time, a dataset was

constructed by combining loan data reported by developing countries to the World Bank

Debtor Reporting System (DRS) – which includes official commitments from a broader set of

bilateral lenders as well as loans from private financiers – with ODA grant and equity

commitments data reported by official finance providers to the OECD Creditor Reporting

System (CRS).

6. Nonetheless, there remain limitations imposed by the underlying characteristics of

the datasets used, with implications for the analysis in this report and the comparison of

its findings with previous Aid Architecture papers. First, while the combination of the

OECD datasets with the World Bank DRS allows to supplement the analysis with information

on financial flows from sovereign donors not reporting consistently to DAC, it does not include

grants from these donors, for which no comprehensive data is available. Second, while the

constructed dataset does provide sufficiently robust data for country-level analysis, differences

in sector and other definitions imply that additional comparisons should be undertaken with

caution. Third, while OECD DAC data is available from 1960 onwards with accuracy in

headline trends, changing definitions over the years suggest that a shorter time period (i.e.,

2000-2019) would be more prudent for the analysis of sectoral trends. Fourth, trend analysis

for country income groups cannot easily be undertaken since the data is based on countries’

income status as of 2019, which may have changed from years of previous comparisons.

4

Finally, since convergence between aggregate data in the DAC database and the transaction-

by-transaction information in the CRS has improved more significantly in the past ten years,

in some cases, trend analysis may be more robust for the most recent decade (i.e., 2010-2019).

The paper notes these data limitations in each relevant section.

7. The paper is organized as follows. Section II looks at the overall financing of the public

sector in developing countries, including the rising importance of non-traditional development

partners. Section III focuses on official finance and analyzes key trends in its distribution by

geographic area, income group, and sector. Section IV examines the continuing complexity of

the global aid architecture through the prisms of proliferation and fragmentation. Finally,

Section V summarizes the main findings of the paper and identifies potential areas for future

research.

5

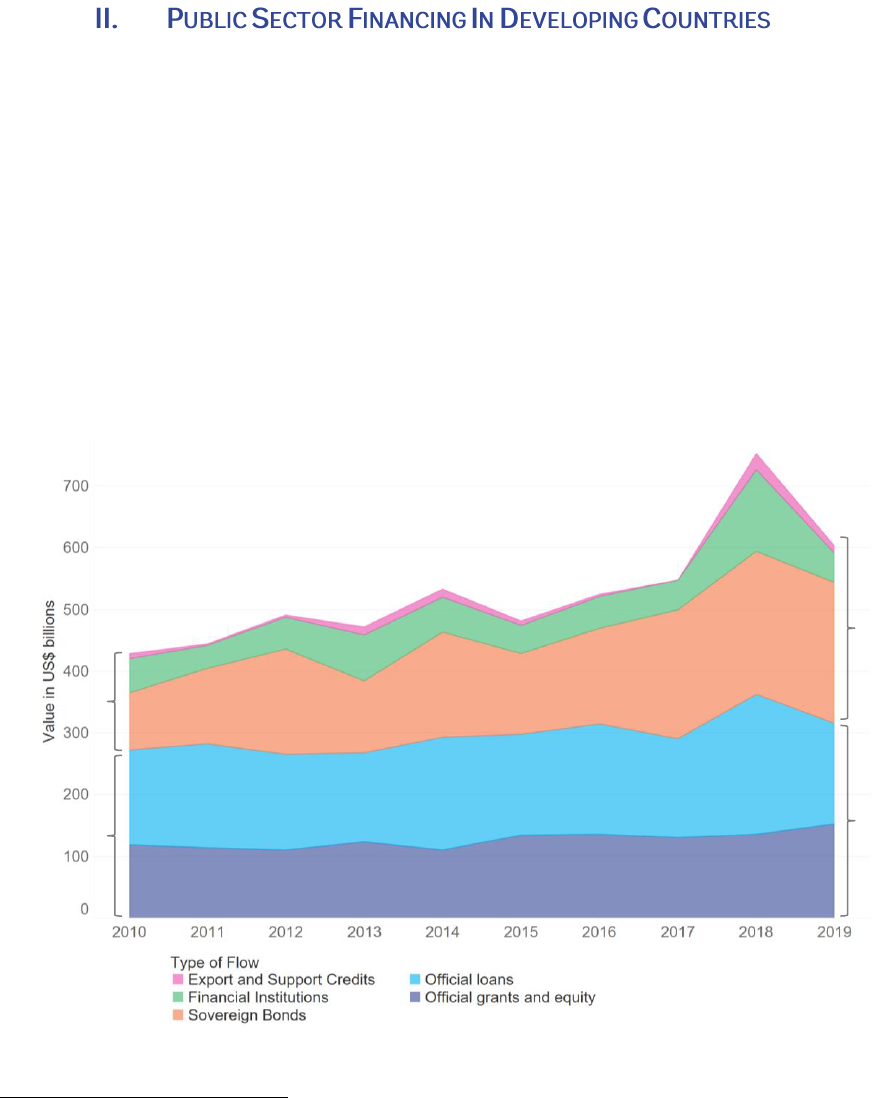

8. Over the last decade, consistent with concerted efforts by the development

community to increase resource mobilization by catalyzing private finance, flows

from private sources increased significantly while those from official sources grew

more slowly; by 2019, the two sources were almost equal in size. Between 2010-2019,

cumulative commitments amounted to US$5.3 trillion in real terms (i.e., at 2019 prices)

with 56 percent provided by official sources and 44 percent from private and non-official

sources (Figure 2).

7

During this period, the development community dedicated a particular

focus on leveraging public finance to catalyze additional resources, particularly from the

private sector.

8

Consistent with these efforts, in 2019, commitments from official sources

stood at US$315 billion (52 percent) as compared with commitments of US$288 billion

from private and non-official sources (48 percent).

Figure 2: Total External Financing to the Public Sector in Developing Countries

(Commitments, US$ billions, 2019 prices)

Source: Authors’ calculations based on World Bank DRS

and OECD CRS (for official grants and equity only)

9

7

In addition to private financial instutions, private and non-official sources also cover lending provided by

financial institutions with state ownership.

8

See, for example, the 2015 Addis Ababa Action Agenda (United Nations, 2015) and the 2015 report “From

Billions to Trillions” prepared by six Multilateral Development Banks and the IMF (Development

Committee, 2015).

9

Data on official loans, sovereign bonds, financial institutions, and export/support credits is based on the

DRS database. Rescheduled commitments are not included in the calculations. Data for the following

64%

36%

48%

52%

6

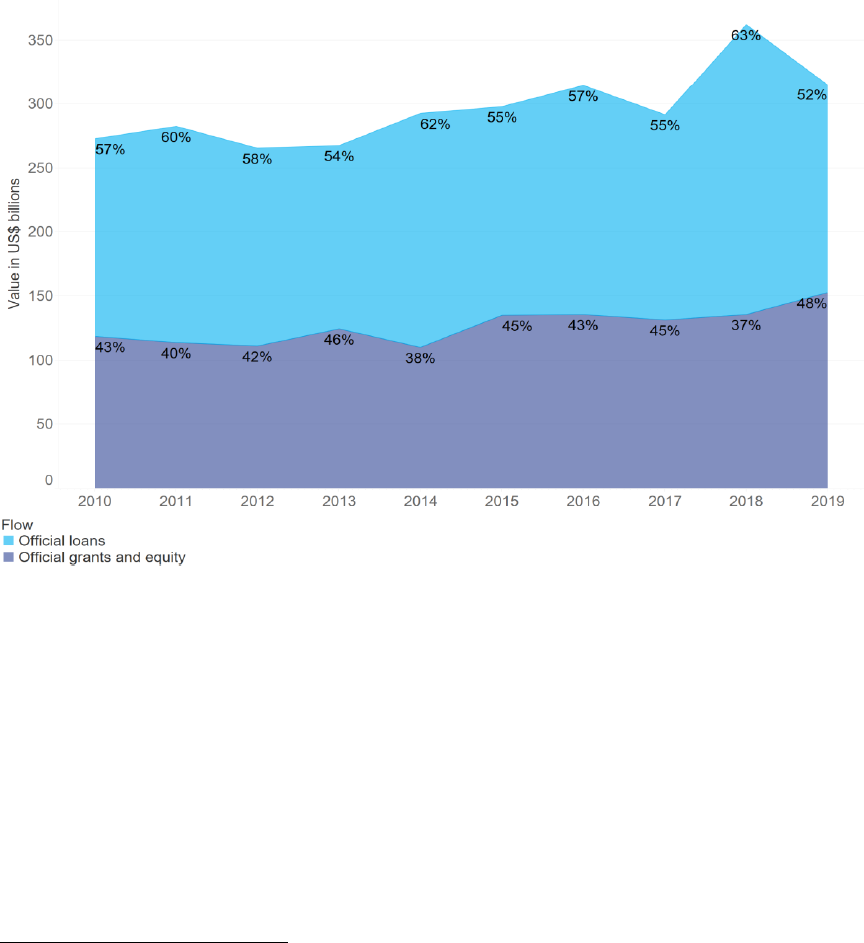

9. Within official sources, the respective shares of loans and grants have remained

relatively stable over the past decade. The share of official loans was 57 percent in 2010

and fluctuated between 54 and 63 even since, to reach 52 percent in 2019 (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Official Finance to Developing Countries

(Commitments, US$ billions and percent of year total, 2019 prices)

Source: World Bank DRS for official loans and OECD CRS for official grants and equity.

10. In the context of mounting debt pressures in many developing countries,

10

discerning the full extent of official loan financing, its sources and destinations, is

particularly important. The rest of this section looks specifically at the volume of public

loans extended to developing countries over the past decade, leveraging the DRS dataset.

The comparison of donors based on their lending volume is not intended as a ranking of

their total support to developing countries or development efforts. If grants were taken into

account, the shares from multilateral institutions and from bilateral donors that provide

significant amounts of grant financing would be larger.

11

However, there is currently a lack

of comprehensive data available on grant financing, particularly from sovereign donors

countries has been estimated for missing years when no report have been received by the World Bank

(indicating the last year of data received): Chad (2015), Eritrea (2009), Somalia (1992), Syrian Arab Republic

(2010), and partially Tanzania (2015).

10

See for instance recent efforts to alleviate debt burdens during the COVID-19 pandemic through the Debt

Service Suspension Initiative (https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/debt/brief/covid-19-debt-service-

suspension-initiative).

11

Similarly, the analysis below in Section II may overestimate the role of donors that provide most of their

support through lending.

7

which do not consistently report to the OECD DAC.

12

Section III of this paper provides a

full overview of all types of flows (grants, concessional and non-concessional loans) to

developing countries for the subset of official donors that do report to DAC. In addition, a

significant share of bilateral donors’ support consists of core contributions to multilateral

organizations. Section III further examines the share of bilateral aid that is implemented by

multilateral organizations.

11. During 2010-2019, official loan commitments by multilateral and bilateral

agencies amounted to US$1.7 trillion. Of this, 57 percent was provided by multilaterals

and 43 percent by bilaterals. Over the ten-year period, the share of loans provided by

multilaterals compared to bilaterals remained relatively stable, but picked up in most recent

years, from 51 percent in 2016 to 71 percent in 2019. At the donor level, the World Bank

Group provided the highest volume of loan financing with a combined US$357 billion

globally over the past ten years, followed by China (US$244 billion), the Asian

Development Bank (US$131 billion), Japan (US$126 billion), and the International

Monetary Fund (US$120 billion) (Figure 4). In addition, the World Bank provided US$34

billion of grants during this time frame through IDA, the fund for the poorest countries,

basically to countries at high or moderate risk of debt distress.

Figure 4: Official Loan Commitments to Developing Countries

(Cumulative commitments 2010-2019, US$ billions at 2019 prices, top 20 providers)

Source: World Bank DRS

12. Over this period, more than half of bilateral loans to developing countries came

from the BRICS, especially from China and Russia and to a lesser extent from India

12

The World Bank DRS does not cover grant financing, since by definition no repayment is required from

recipients.

8

and Brazil.

13

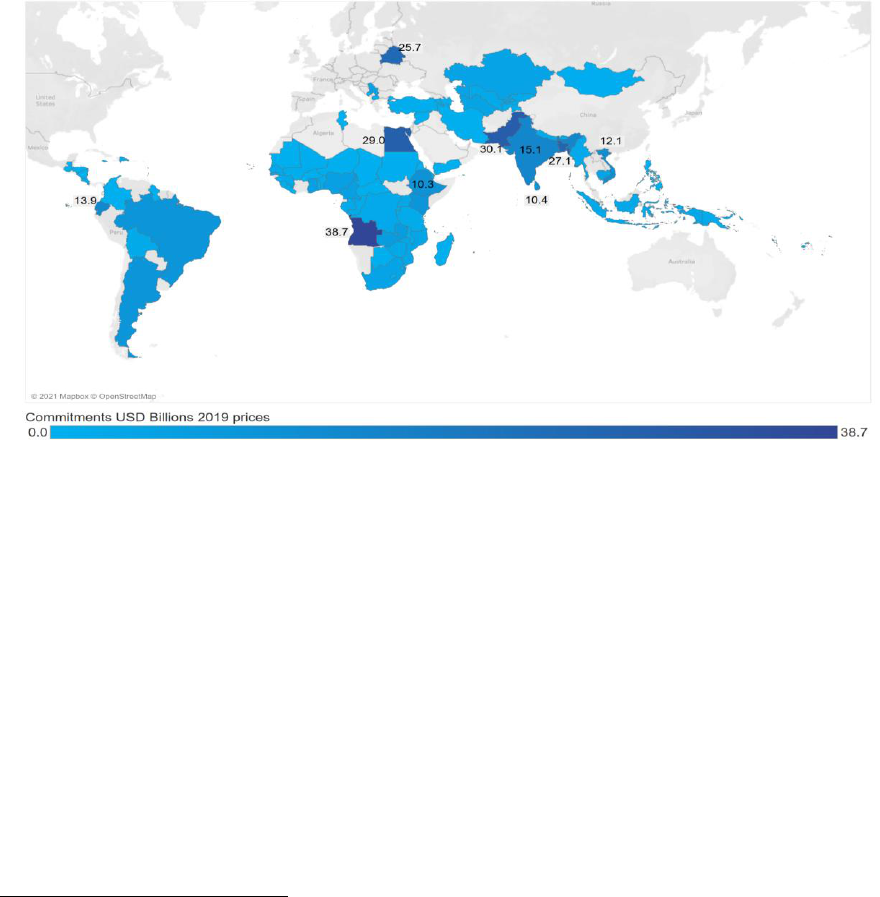

Country coverage cut across regions, with largest recipients of BRICS loans

being Angola (US$38.7 billion), Pakistan (US$30.1 billion), Egypt (US$29 billion),

Bangladesh (US$27.1 billion), Belarus (US$25.7 billion), India itself (US$15.1 billion),

Ecuador (US$13.9 billion), Vietnam (US$12.1 billion), Sri Lanka (US$10.4 billion), and

Ethiopia (US$10.3 billion) (Figure 5). Intra-BRICS lending amounted to US$29 billion

(8% of total BRICS lending).

14

Largest destination sectors for BRICS loans were the

financial sector, energy production and transmission, and transport.

Figure 5: BRICS Loan Commitments by Recipient Country

(Cumulative loan commitments 2010-2019, US$ billions at 2019 prices, top 10 recipients labeled)

Source: World Bank Debtor Reporting System (DRS)

13. The combination of the DRS and CRS datasets provides a broad picture of

aggregate flows globally, but holds limitations in the level of analysis possible. As

previously noted, for the first time, this analysis combined data from the World Bank DRS

for official loans and private finance and from the OECD CRS for ODA grants and equity

commitments. Over the ten-year period analyzed, a larger number of countries and

providers of official loans reported to DRS than to the OECD, so that official loans reported

to DRS were 19 percent higher than those reported to CRS. While the combined dataset

provides a more accurate picture of aggregated financial flows to developing countries, it

cannot easily be utilized for a more granular analysis of underlying dimensions of interest,

such as donor agencies, transaction channels, or transaction purpose. Consequently,

Section II drew a number of key insights that could be extracted from the combined dataset

and from DRS, while Section III leverages the full depth of the CRS dataset to provide a

more exhaustive analysis along other categories of interest.

13

Recent reports have also identified the growing role of emerging providers. See for instance: OECD, 2020.

14

The World Bank Debtor Reporting System indicates that over the past ten years, India received US$15.1

billion in loans from Russia, Brazil received US$9.8 billion from China, and South Africa received US$4.1

billion from China.

9

14. This section examines the composition of official financial support to developing

countries using key variables such as country income group, sector, and geographic

location. Trends were analyzed for a slightly longer horizon than in Section II, covering

the 2000-2019 period, and were reviewed at three levels. First, the analysis reviewed all

Official Financial Flows (OFF), that is ODA and OOF combined. Second, the focus was

narrowed to ODA only for all developing countries. Finally, it was further narrowed to

ODA for IDA-eligible countries only. The analysis in this section was undertaken based

on data reported by official bilateral, multilateral, and other agencies to the OECD (i.e., to

the DAC and CRS databases).

15. Globally, OFF grew from US$111 billion a year in 2000 to pass the bar of

US$200 billion by 2008 and reach an all-time high of US$319 billion in 2019. Over that

period, OFF increased in real terms by 187 percent or a compound real growth rate of 5.7

percent per annum. OFF consist of four types of flows – ODA grants, ODA concessional

loans, Other Official Flows (i.e., non-concessional loans), and equity investments

16

–

which increased at differing rates since 2000.

16. Seventy percent of global OFF commitments over the 2000-2019 period were

concessional ODA (consisting of over 50 percent ODA grants, 19 percent ODA loans

and less than 1 percent equity investments) and 30 percent were OOF (Table 1).

Growth patterns varied among the different types of flows. ODA grants grew most rapidly

until 2006, before continuing to grow but at a slower pace ever since. ODA loans remained

relatively stable until 2006, before starting to pick up until 2017, and have now decreased

two years in a row. OOF (i.e., non-concessional loans) also remained stable until 2006

before growing rapidly ever since, at a faster pace than ODA grants and ODA loans. While

OOF constituted 27 percent of OFF in 2000, this share increased to 36 percent today.

17

15

Private philanthropy is excluded from this analysis since data is only available as summary figures (in

DAC tables) and flows to recipient governments could not be separately identified. In 2019, $8.6 billion were

reported as financing flows from private philanthropy.

16

Equity investments for the official sector do not include private-to-private equity flows (i.e., Foreign Direct

Investments).

17

These findings are consistent with recent reports, such as OECD, 2020, which provides additional insights

on the rise of non-concessional finance.

10

Table 1: Official Financial Flows to Developing Countries by Type of Flow

(Cumulative commitments 2000-2019, US$ billions at 2019 prices)

Total

US$ bn

%

ODA Grants

2,182

50

ODA Loans

818

19

Equity

25

1

Subtotal ODA

3,024

70

OOF

1,291

30

Total

4,316

100

Source: CRS

17. Over the period 2000-2019, the composition of concessional vs. non-concessional

resources and the distribution of concessional resources varied across country income

groups, i.e., Least Developed Countries and Low-Income Countries (LDCs/LICs) and

Middle-Income Countries (MICs).

18

18. LDCs/LICs received 94 percent of their financing as concessional resources,

whereas MICs received 56 percent as concessional resources. Specifically, LDCs/LICs

received US$661 billion (69 percent of OFF) of financial resources as ODA grants,

US$241 billion (25 percent) as ODA loans and US$54 billion (6 percent) as OOF, while

MICs received US$831 billion (33 percent) as ODA grants, US$556 billion (22 percent)

of ODA loans and US$1.1 trillion (44 percent) as OOF. Flows unallocated to specific

recipient countries largely took the form of ODA grants (Table 2).

Table 2: Official Financial Flows by Income Group

(Cumulative commitments 2000-2019, US$ billions at 2019 prices and

% of total OFF per country income group)

LDCs/ LICs

MICs

Unallocated

US$ billion

%

US$ billion

billion

%

US$ billion

%

ODA Grants

661

69

831

33

689

79

ODA Loans

241

25

556

22

20

2

Equity

2

0

9

0

14

2

Subtotal ODA

905

94

1,396

56

723

83

OOF

54

6

1,093

44

144

17

Total

959

100

2,490

100

867

100

19. Over the period, official financing flows increased across all income groups. For

LDCs/LICs, grants increased from US$16 billion a year in 2000 to US$46 billion in 2019,

18

Current (i.e., 2019) Country Income Groups classification used for reporting historical trends. Country

Income Group data in this report should not be compared with similar data presented in previous editions of

this paper due to changing country composition of each group.

Source: CRS

11

but this increase was proportionally lower than that of ODA loans and OOF, which now

constitute 23 and 12 percent of OFF to LDCs/LICS, respectively (with grants still

accounting for the remaining 65 percent). For MICs, OOF (i.e., non-concessional loans)

increased from US$26 billion in 2000 to US$93 billion in 2019, and grew proportionally

faster than other type of flows (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Evolution of Official Financial Flows by Country Income Group

(Commitments 2000 to 2019, US$ billions, 2019 prices)

20. Looking at the distribution by type of flows, almost half of ODA commitments

over the past two decades went to MICs, reflecting their large population size, while

LDCs/LICs received one third of ODA. Specifically, LDCs and LICs received 30 percent

of all ODA grants, 30 percent of all ODA loans and 4 percent of OOF commitments. MICs

received 38 percent of all ODA grants, 68 percent of all ODA loans and 85 percent of all

OOF commitments. Interestingly, 32 percent of grants over the past decade were

unallocated to specific recipient countries (Table 3).

Table 3: Distribution of Official Flows by Country Income Group

(Cumulative commitments 2000-2019, percentage of flow type total)

LDCs/ LICs

MICs

Unallocated

Total

ODA Grants

30

38

32

100

ODA Loans

30

68

2

100

Equity

8

36

57

100

Subtotal ODA

30

46

24

100

OOF

4

85

11

100

Total

22

58

20

100

Source: CRS

Source: CRS

12

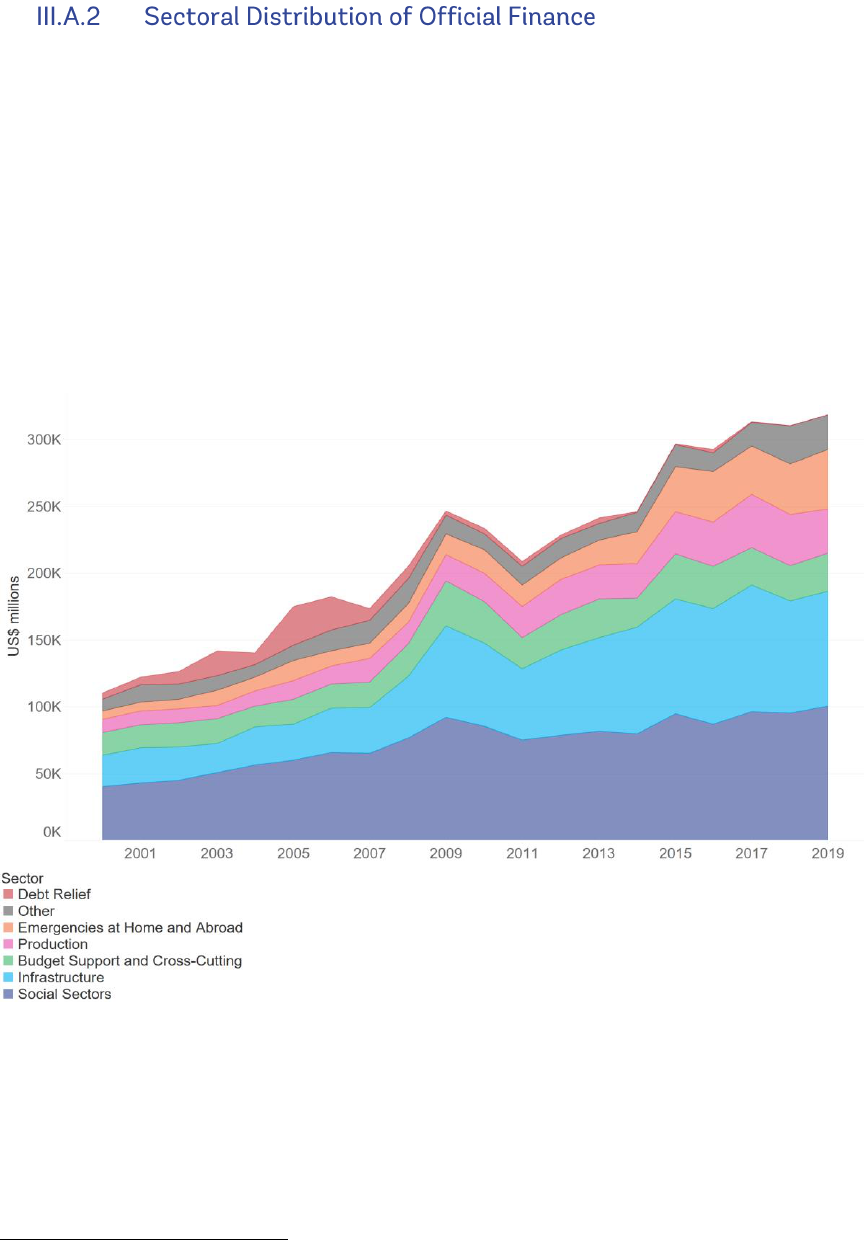

21. The significant real growth (188 percent) in OFF since 2000 resulted in volume

increases for all sectors (Figure 7).

19

For example, social sectors grew from US$40

billion to US$101 billion a year, infrastructure grew from US$23 billion to US$86 billion,

emergencies at home and abroad grew from US$6 billion to US$44 billion and production

grew from US$10 billion to US$34 billion. Overall, commitments to social sectors

constituted a third (34 percent) of all OFF commitments and commitments to infrastructure

represented a quarter (26 percent). Eleven percent went to budget support, 10 percent to

production, 9 percent to emergencies at home and abroad, 7 percent to other categories,

and 4 percent to debt relief.

Figure 7: Sectoral Distribution of Official Financial Flows

(Commitments, US$ millions, 2019 prices)

22. Three sectors grew proportionally faster than others over that period:

emergencies at home and abroad (from 5 percent in 2000 to 14 percent in 2019),

infrastructure (from 21 to 27 percent) and to a lesser extent, production (from 9 to 11

percent). In contrast, three sectors experienced declining shares: budget support (from 15

to 9 percent), social sectors (from 36 percent to 32 percent), and debt relief (from 4 to less

than one percent). Emergencies include expenditures undertaken for humanitarian aid in

developing countries and the cost of refugees incurred in donor countries. Both sub-

19

Sector definitions in this report draw largely on DAC sector classifications but summarizes them further

in some cases. Please see Sector Classifications in the Annex for details.

Source: CRS

13

categories increased over the period, from US$5 billion to US$34 billion for humanitarian

aid abroad and from US$1 billion to US$10 billion for refugees at home. Growth rates

were relatively similar from 2000 to 2009, but commitments to refugees in donor countries

increased proportionally faster over the last decade, with a Compound Annual Growth Rate

(CAGR) of 14 percent versus 10 percent for humanitarian aid.

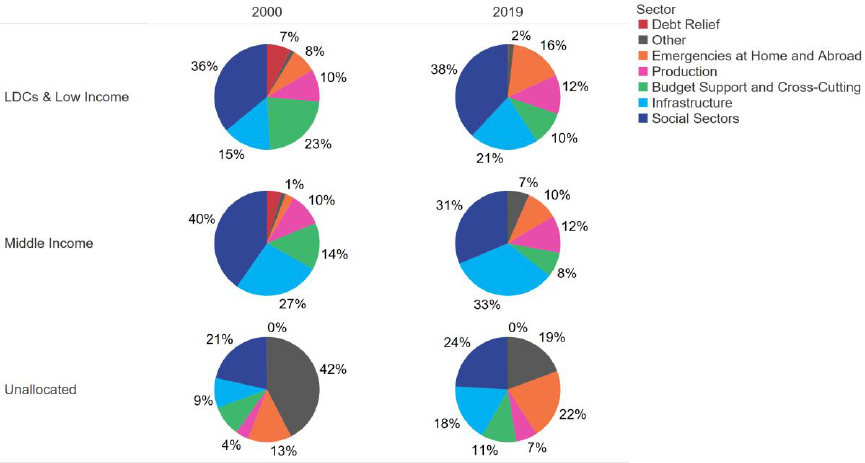

23. Changes in OFF sectoral distribution differed across country income groups.

Specifically, commitments to social sectors increased proportionally faster than

commitments to other sectors in LDCs/LICs (from 36 to 38 percent of OFF) but decreased

proportionally to other sectors in MICs (from 40 to 31 percent). In contrast, commitments

to infrastructure, production, and emergencies at home and abroad all proportionally

increased across all country income groups, while commitments to budget support

decreased (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Sectoral Distribution of Official Flows by Income Group

(Commitments 2000 vs. 2019, % of year total)

Source: CRS

24. Sectoral distribution of OFF differed significantly between grants and loans,

but was similar for concessional and non-concessional loans. ODA grants commitments

focused mostly on social sectors over the past 20 years, and more recently also on

emergencies at home and abroad. Together, these two sectors received two thirds of ODA

grants commitments over the past five years. Only 13 percent of ODA grants went to the

infrastructure and production sectors. In contrast, ODA loans, OOF, and equity investments

focused primarily on infrastructure, the share of which increased for each type of flow

during the period analyzed, from 33 to 47 percent for ODA loans, from 33 to 45 percent

for OOF, and from 51 to 59 percent for equity. Significant shares of ODA loans and OOF

also initially went to social sectors, but these decreased proportionally over time while

14

shares for loans for budget support and for production increased (Figure 9).

20

Many MDBs

choose to allocate ODA grants primarily based on recipient countries’ debt outlook instead

of the sector where the commitment is made, although data suggests that the allocation of

grants to countries facing high risk of debt distress has decreased in recent years

proportionally to other types of flows (Box 2).

Figure 9: Sectoral Distribution by Type of Flows

(% of five-year average)

Source: CRS

20

In 2019, the OECD introduced the concept of “transition finance”, which examines the evolution of sources

of financing as countries progress through different development stages (Piemonte et al., 2019). The analysis

of transition finance provides a dynamic perspective to the sectoral distribution of OFF and suggests that the

evolution of types of flows along development stages varies across sectors, with longer dependence on ODA,

especially grants, for certain sectors like health.

15

25. The volume of OFF which donors have not identified as allocated to specific

recipient countries almost quadrupled over the past 20 years, mostly due to an

increase in commitments for emergencies and for global and regional public goods.

OFF not assigned for specific recipients increased from US$18 billion a year in 2000 to

US$70 billion a year in 2019, and now represent 22 percent of total OFF to developing

countries. There appears to be two main reasons for the observed growth in country

unallocated OFF:

• The significant increase of commitments for emergencies at home and abroad (i.e.,

i.e., humanitarian aid and support to refugees in donor countries, which by definition

cannot be easily geographically predicted), which grew significantly over the past

two decades, from US$2.2 billion in 2000 (13 percent of country unallocated OFF)

to almost US$15 billion today (22 percent) (Figure 10 – top graph).

• The increase in commitments “beyond the country level”, e.g., to regional programs,

which grew most significantly over the past five years, from US$15 billion in 2014

(31 percent of country unallocated OFF) to almost US$28 billion in 2019 (40

percent) (Figure 10 – bottom graph).

Box 2: OFF to Countries with Debt Vulnerabilities

Through the joint World Bank-IMF Debt Sustainability Framework for Low-Income Countries, the two

institutions produce regular Debt Sustainability Analyses (DSA), whereby countries are classified

according to their risk of external debt distress. Over the last decade, the number of countries assessed

to be at high risk of external debt distress or in debt distress decreased from 23 in 2010 to 16 in 2014,

before increasing progressively up to 33 in 2019.

i

During this period, the share of ODA grants in official

flows to countries facing high debt vulnerabilities declined from 93 in 2000 to 62 percent in 2018, while

the share of ODA loans and other OOF rose from 7 to 38 percent. A reversal in this trend was observed

in 2019 with an increase in the proportion of grants to 76 percent.

These observations contrast with the

approach adopted by most MDBs which allocate grants primarily based on recipient countries’ debt

outlook, suggesting that many other donors may not have aligned their terms of financing solely based

on these considerations, or are doing so only with a lag.

Source: CRS and Historical List of Risk of External Debt Distress

i

The graph reflects the changing composition of the group along the years.

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019

Composition of OFF to countries assessed to be at high risk of

external debt distress or in debt distress

(% of year total)

ODA Grants ODA Loans OOF

16

Many activities with a global public good or regional approach, including those from

MDB regional windows and Financial Intermediary Funds (FIFs),

21

would ultimately be

allocated to individual countries. Despite this, OFF unallocated to specific countries has

been on the rise. This may suggest a growing trend of a larger role being given to regional

organizations to act on behalf of groups of countries, although additional analysis would

be useful to better understand this phenomenon.

Figure 10: Distribution of OFF Unallocated to Specific Recipient Countries

(Commitments, US$ millions, 2019 prices)

Source: OECD CRS

26. The growth in OFF from US$111 billion in 2000 to US319 billion in 2019

benefited all regions. In 2019, Sub-Saharan Africa received US$73 billion (up from

US$26 billion in 2000), South and Central Asia received US$53 billion (up from US$13

billion), Middle East and North Africa received US$50 billion (up from US$11 billion),

Central and South America received US$45 billion (up from US$23 billion), East Asia and

Pacific received US$37 billion (up from US$19 billion) and Europe received US$19 billion

(up from US$9 billion). Over the 2000-2019 period, Sub-Saharan Africa received 23

percent of OFF commitments followed by South and Central Asia (16 percent), Central

and South America (15 percent), East Asia and the Pacific and Middle East and North

21

FIFs are a special type of trust fund that provide large-scale funding for broad, coordinated interventions,

usually focused on themes, and typically aimed at achieving global public goods.

17

Africa (13 percent) and Europe (7 percent). Thirteen percent of commitments were not

regionally allocated (Figure 11). OFF to fragile and conflict-affected states, which are

spread across all regions of the world, is analyzed in Box 3.

Figure 11: Official Financial Flows by Regions

(Commitments, US$ millions, 2019 prices)

Box 3: OFF to Fragile Countries

There exist multiple lists of fragile countries, including the OECD’s States of Fragility and the Fund For

Peace’s Fragile States Index. Since 2006, the World Bank Group has been releasing a list of fragile and

conflict-affected situations (FCS), which include countries affected by violent conflict (based on the

number of deaths relative to the population) and countries with high levels of institutional and social

fragility (based on indicators measuring the quality of policies and institutions).

i

Over the period

analyzed, the number of FCS countries on the WBG list remained relatively stable, from 35 in 2006 to

33 in 2012 and 36 in 2019. Official financial flows to these countries have increased globally,

particularly in most recent years, reaching US$106 per capita in 2019.

ii

This evolution may suggest a

growing focus from official donors on the issues of fragility, conflict, and violence which affect

development outcomes.

Sources: CRS for commitment data, World Development Indicators for population data,

and WB List of Fragile and Conflict-Affected Situations

i

See: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/fragilityconflictviolence/brief/harmonized-list-of-fragile-situations

ii Per capita amounts used due to evolving nature of the list and its changing composition every year.

$0

$20

$40

$60

$80

$100

$120

2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019

OFF Commitments per capita to FCS

(US$ at 2019 prices)

OOF p.c.

ODA Loans p.c.

ODA Grants p.c.

Source: CRS

18

27. After a protracted decline during the 1990s, ODA has been growing steadily

since 2000. ODA commitments increased from US$80 billion in 2000 to US$204 billion

in 2019, while disbursements increased from US$32 billion to US$192 billion. This

positive trend is illustrated in Figure 12 and holds true irrespective of whether aggregate or

detailed ODA commitments or disbursements are analyzed.

22

Figure 12: ODA Commitments and Disbursements since 2000

(US$ millions, 2019 prices)

28. This sub-section primarily utilizes data on ODA grants and loan commitments, but

also leverages disbursement data where trends are better reflected (or only captured) this

way. To allow for comparability of data across the extended time period, the remainder of

the analysis is presented in constant 2019 prices.

29. Country income group. As previously noted, 30 percent of ODA commitments

between 2000 and 2019 were provided to LDCs/LICs, 46 percent to MICs, and 24 percent

were unallocated to specific recipient countries.

30. Sectoral distribution. Between 2000 and 2019, sector allocable ODA

23

increased

substantially from US$76 billion to US$208 billion. In 2019, social sectors received US$78

22

At the start of the period, there were significant differences between aggregate reporting (from DAC tables)

and detailed reporting (from CRS), particularly for gross disbursements. By the end of the period, divergence

between the two had reduced to less than 4 percent.

23

DAC defines “sector allocable ODA” as all ODA flows aimed at fostering a particular sector in the

recipient country, and thus excludes all the contributions that are not susceptible to allocation by sector (e.g.,

balance-of-payments support, actions related to debt, emergency assistance, internal transactions in the donor

country, administrative costs of donors, support to NGOs, as well as unallocated or unspecified ODA).

Source: CRS

19

billion (up from US$27 billion), infrastructure received US$35 billion (up from US$13

billion), emergencies at home and abroad received US$42billion (up from US$6 billion),

budget support received US$24 billion (up from US$15 billion) and production received

US$18 billion (up from US$6 billion). While all sectors experienced growth over the

period analyzed, proportional distribution across sectors varied. Emergencies at home and

abroad increased proportionally faster than other sectors (from 7 percent to 20 percent);

just as infrastructure (from 16 to 17 percent). In contrast, budget support declined (from 19

percent to 11 percent) as did debt relief (from 6 percent to less than one percent). The

proportion of social sector commitments remained largely unchanged from the beginning

to the end of the period (at 36-37 percent) though it peaked at 44 percent in 2007 and 43

percent in 2009 (Figure 13).

Figure 13: ODA Commitments by Sector

(US$ millions, 2019 prices)

31. Regional distribution. Sub-Saharan Africa’s share of total ODA has been growing

for nearly half a century, from roughly 22 percent in the 1960s and 1970s to about 35

percent in the 2000s, hitting a peak of 56 percent in 2006, before declining to 40 percent

in the early 2010’s and landing at 37 percent by 2019 (Figure 14). Several factors

contributed to the increases observed. For example, the 2006-increase was due to debt relief

operations, including the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI). South and Central

Asia, the Middle East and North Africa, and Far East Asia have also remained major ODA

recipients over the entire period, although their respective shares have been fluctuating.

Source: CRS

20

Figure 14: Gross Official Development Assistance by Region

(Gross disbursements, US$ billions, 2019 prices)

32. Country programmable Aid (CPA) is a narrower measure introduced in 2007

as a proxy to better estimate ODA over which partner countries have a significant say

for programming purposes.

24

Over the 2000-2019 period, the share of CPA in ODA

declined from 69 percent to 56 percent due to a slow growth rate of only 3.6 percent per

year (Figure 15).

24

CPA consists of gross ODA disbursements by recipient but excludes spending which is: (1) inherently

unpredictable (humanitarian aid and debt relief); (2) entails no flows to the recipient country (administration

costs, student costs, development awareness and research and refugee spending in donor countries); or (3) is

usually not discussed between the main donor agency and recipient governments (food aid, aid from local

governments, core funding to NGOs, aid through secondary agencies, ODA equity investments and aid which

is not allocable by country). In addition, CPA does not net out loan repayments, as these are not usually

factored into aid allocation decisions.

Source: DAC Tables 2a and 2b

21

Figure 15: Evolution of ODA by Type

(Gross disbursements, US$ millions at 2019 prices)

33. Despite accounting for more than half of ODA disbursements, the share of CPA

has shown a decline in recent years due to increasing allocations for emergencies at

home and abroad and for global, regional, and donor programmed activities. The

share of CPA against non-CPA categories declined from 69 percent in 2000 to 56 percent

in 2019. For the purpose of this analysis, non-CPA expenditures were clustered into three

categories: emergencies at home and abroad (combining expenditures on refugees in donor

countries and humanitarian assistance in recipient countries); global, regional and donor

programmed activities (combining all expenditures that could not be allocated to a specific

developing country); and debt relief. The share of emergencies at home and abroad grew

from 11 percent to 21 percent (8.3 percent annual growth rate) and the share of global,

regional or donor programmed activities grew from 16 percent to 23 percent (6.5 percent

annual growth rate). Debt relief, which had been significant early in the last decade with a

peak of 39 percent of ODA in 2006, has declined substantially to less than one percent by

2019 (Table 4).

Table 4: Growth in ODA categories between 2000 and 2019

2000

US$

billion

2000-2019

Real

Increase

US$ billion

CAGR

2000-

2019

%

share

2000

%

share

2019

Country Programmable Aid

55.3

52.2

3.6%

69

56

Emergencies at home and abroad

8.8

31.6

8.3%

11

21

Global, regional or donor programmed activities

13.0

30.4

6.5%

16

23

Debt relief

3.4

-2.6

-7.5%

4

0

Total ODA

80.5

111.6

4.7%

100

100

Source: CRS and CPA database

Source: CRS and CPA database

22

34. The declining share of CPA is also apparent when disaggregating ODA by

country income group.

25

The trend of reducing share of CPA in net ODA is however more

pronounced for MICs than for LDCs/LICs. For instance, in 2019 CPA for LDCs/LICs

stood at 75 percent (US$43.7 billion) of net ODA, which is marginally less than the 78

percent (US$15.9 billion) observed in 2000. CPA for MICs also declined, from 85 percent

(US$34.5 billion) in 2000 to 69 percent (US$53.9 billion) in 2019.

35. The share of ODA contributed by bilateral donors has remained relatively

stable since 2000, at about 69 percent of total aid flows.

26

This relative share of funding

has been consistent since the mid-1970s. A breakdown by type of ODA is provided in

Figure 16. Bilateral donors contributed 64 percent of total CPA, 70 percent of global,

regional, and country unallocated activities, and 82 percent of humanitarian aid.

Figure 16: Distribution of Bilateral and Multilateral ODA by Type

27

(Gross disbursements, percent shares, 2000-2019)

Source: OECD DAC Table 2a

36. A significant share of bilateral ODA is implemented by multilateral

organizations, although core (non-earmarked funding) has decreased. Core or

multilateral ODA refers to donor contributions made to a recipient institution that (i)

conducts all or part of its activities in favour of development, (ii) is an international agency,

institution or organization whose members are governments or a fund managed

autonomously by such agency, and (iii) pools contributions so that they lose their identity

and become an integral part of its financial assets. In contrast, non-core or multi-bi ODA

refers to donor contributions earmarked for a specific sector, theme, country or region

through a multilateral institution (e.g., through a trust fund). Between 2011 to 2019, the

average share of bilateral ODA flows implemented by multilateral organizations amounted

to 52 percent, with 30 percent as core contributions and 22 percent as non-core (i.e.,

25

Given the significant amount of funding unallocated to specific recipient countries, CPA – which is

computed only at the country level – tends to show a higher proportion when computed by country income

category.

26

Total aid flows include the combined totals of bilateral and multilateral aid flows (excluding debt relief).

27

To allow for comparison of CPA and non-CPA ODA, this Figure uses disburement data. Other Figures in

this sub-section use commitment data. Comparisons should be undertaken with caution.

23

earmarked or “multi-bi”).

28

However, the overall use of multilateral channels by bilateral

donors declined over the period, as core contributions dropped from 37 percent of bilateral

ODA in 2011 to only 29 percent in 2019, while non-core contributions increased, but more

modestly, from 17 percent in 2011 to 23 percent in 2019 (Figure 17).

Figure 17: Implementation Channels for Bilateral ODA

29

(Commitments, percentages of total ODA)

Source: OECD DAC – Members' total use of the multilateral system (CRS)

37. In the 2010s, the largest and fastest growing multilateral channel was the United

Nations. The UN’s share of multilateral ODA increased from 28 percent in 2011 to 40

percent in 2019 as it received US$14.6 billion of additional funding (CAGR of 8.8 percent).

The growth was primarily in non-core (“multi-bi”) contributions (US$12.6 billion or a

CAGR of 10.7 percent) with only a modest increase in core contributions. Core

contributions to the EU institutions, the World Bank Group, and other multilateral

institutions

30

have grown more slowly, with increases balanced across core and non-core

contributions (Figure 18).

28

The balance of 48 percent was implemented by other channels such as the recipient country, the donor

itself, NGOs, or the private sector.

29

Data is shown only from 2011 onwards since earlier data is not available in a comprehensive fashion.

30

Other multilaterals cover primarily the IMF, WTO, as well as other smaller multilateral institutions.

Implem. by multilat

.

Implem. by other

channe

ls

24

Figure 18: ODA to and through Major International Organizations

(Commitments, US$ millions at 2019 prices)

Source: OECD DAC– Members' total use of the multilateral system (CRS)

38. Total ODA to IDA-eligible countries

31

has increased over time, with IDA’s share

increasing marginally. ODA gross flows to IDA-eligible countries nearly tripled in real

terms between 2000 and 2019 with a CAGR of 6.2 percent. IDA’s share of gross

disbursements increased from 12 percent in 2000 to 14 percent in 2019. For IDA-eligible

countries, financing from other multilaterals grew at a marginally slower rate compared to

IDA’s growth during the period (7.1 percent vs. 7.5 percent). Humanitarian aid grew

twelve-fold at a CAGR of 15 percent. The share of total debt relief in total ODA for IDA

countries peaked at 24 percent in the 2006, then fell back to 14 percent in 2011-12 and

became negligible thereafter.

39. IDA-eligible countries received more ODA as CPA in the 2000s than they did

on average during the 1990s, with IDA’s share increasing faster than other donors.

IDA’s share of country programmable aid for IDA-eligible countries grew, on a gross

disbursement basis, between 2000 and 2019, with a peak in 2019 and a low in 2006.

Between 2000 and 2019, IDA’s cumulative CPA was US$160 billion (at 2019 prices), or

about 19 percent of total CPA to IDA-eligible countries. Over the 2000-2019 period, CPA

provided by IDA grew by 270 percent in real terms, which was higher than the 243 percent

for other multilateral institutions and the 121 percent for bilateral donors (Figure 19).

31

IDA-eligible countries based on World Bank FY20 list.

25

Figure 19: Gross ODA Disbursements

to IDA-eligible Countries by Type and Source

(US$ million at 2019 prices, 2000-2019)

Source: DAC Table 2a and CRS

26

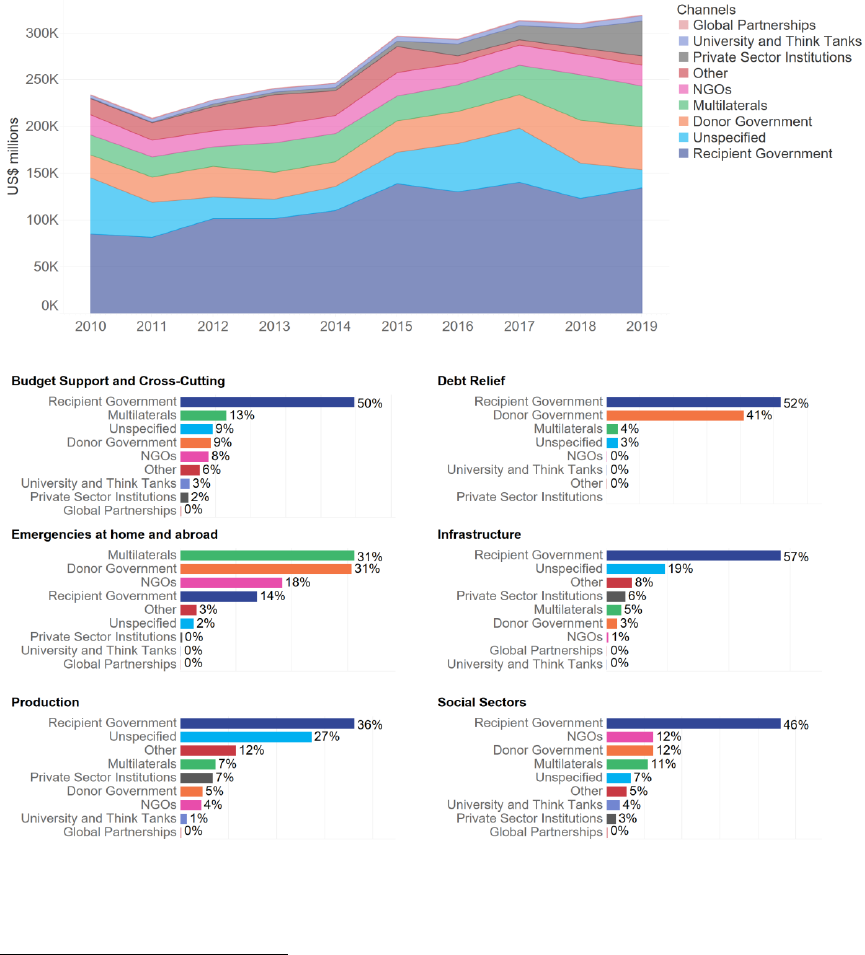

40. The global aid architecture has become increasingly complex. The past two

decades have been characterized by a proliferation of bilateral official finance providers

and of entities providing official finance in these countries; a growing number of

international organizations, funds, and programs, many of which are specialized in a

particular sector or theme; and an overall growth in private philanthropy (OECD, 2020).

32

These phenomena contributed to the progressive fragmentation of official finance into a

larger number of activities of smaller unit size at the recipient country level.

33

The first part

of this section discusses trends in proliferation in official finance, while the second reviews

trends in fragmentation of official finance.

41. The number of official finance providers and of entities providing official

finance increased significantly since 2000, largely through the emergence of new

bilateral donors and the multiplication of government agencies providing official

finance. The number of bilateral donors increased from a yearly average of 25 providers

during the 2000-2004 period to 43 providers during the 2015-2019 period, while the

number of multilateral donors increased more subtly from 22 to 27 over the same

period.

34

,

35

The number of entities providing official finance (i.e., agencies within donor

countries or organizations) increased even more dramatically during this period; from 145

bilateral entities in 2000-2004 to 411 in 2015-2019 (a 183-percent increase) and from 46

multilateral entities to 91 (a 98-percent increase) (Figure 20). This may be due partly to the

lack of full reporting at the beginning of the period.

42. The growth in entities providing official finance was a widespread phenomenon,

although particularly concentrated among bilateral donors. During the 2000-2004

period, 12 official finance providers (11 bilaterals and one multilateral, together

representing about one fourth of all providers) reported commitments made by more than

5 different entities (for a total of 135 entities). By 2015-2019, this number had increased to

32 providers (27 bilaterals and five multilaterals, now representing almost half of all

providers), committing resources through no less than 424 entities (Table 5).

32

About 8 percent of all reported official aid to developing countries has been provided through NGOs and

public-private partnerships.

33

Alternate terminology refers to proliferation of official finance providers and entities providing official

finance as source proliferation and proliferation of implementing agencies as use proliferation. Source

proliferation does not necessarily lead to use proliferation if activities are pooled at the country, sub-regional,

or regional levels.

34

Donor and entity counts extracted from the CRS database were corrected to address the issue of donors

only starting to report to the OECD at the activity level in the later years of the period analyzed. The

correction was done by comparing donor reporting at the aggregate level in the DAC database and by

analyzing public information on (i) the years when donors officially started their OFF contributions and (ii)

when entitites were established. This approach reduces the impact of CRS underreporting and ensures that

the observed growth in the number of donors and entitites is indeed mostly due to proliferation. Despite these

efforts, a marginal impact of underreporting, particularly at the entity level, cannot be completed excluded.

35

Calculations were made using five-year averages to reduce year-to-year fluctuations.

27

Figure 20: Proliferation of Official Financial Providers and Entities

Source: OECD/DAC – CRS, including corrections from authors

to address underreporting by official donors in earlier years

Table 5: Official Finance Providers by Number of Entities

No. of Official Finance Providers

No. of Entities Providing Official

Finance

2000-

2004

2005-

2009

2010-

2014

2015-

2019

2000-

2004

2005-

2009

2010-

2014

2015-

2019

Bilaterals

1 to 4 entities

14

10

12

16

28

25

26

40

5 to 9 entities

4

8

9

8

30

56

58

53

10 or more entities

7

8

14

19

87

107

228

318

Subtotal Bilaterals

25

26

35

43

145

188

312

411

Multilaterals

1 to 4 entities

21

22

22

22

28

30

35

38

5 to 9 entities

0

0

3

3

0

0

20

20

10 or more entities

1

1

1

2

18

19

19

33

Subtotal Multilaterals

22

23

26

27

46

49

74

91

All Providers

1 to 4 entities

35

32

34

38

56

55

61

78

5 to 9 entities

4

8

12

11

30

56

78

73

10 or more entities

8

9

15

21

105

126

247

351

Total

47

49

61

70

191

237

386

502

Source: OECD/DAC – CRS, including corrections from authors

to address underreporting by official donors in earlier years

43. A diverse set of delivery channels and implementing agencies also add to

implementation complexity, although it is not possible to fully measure the extent of this

proliferation. Donor governments themselves implemented only a small portion of the

activities they funded; in the 2010-2019 period, they implemented only 12.5 percent of their

25

22

26

23

35

26

43

27

Bilateral Providers Multilateral Providers

Number of Official Finance Providers

145

46

188

49

312

74

411

91

Bilateral Entities Multilateral Entities

Number of Entities Providing Official

Finance

2000-2004

2005-2009

2010-2014

2015-2019

28

commitments.

36

Logically, recipient governments were the dominant channel of

implementation during this period (43 percent of commitments), followed by donor

governments, multilaterals (11 percent), and NGOs (8 percent) (Figure 21). In the later part of

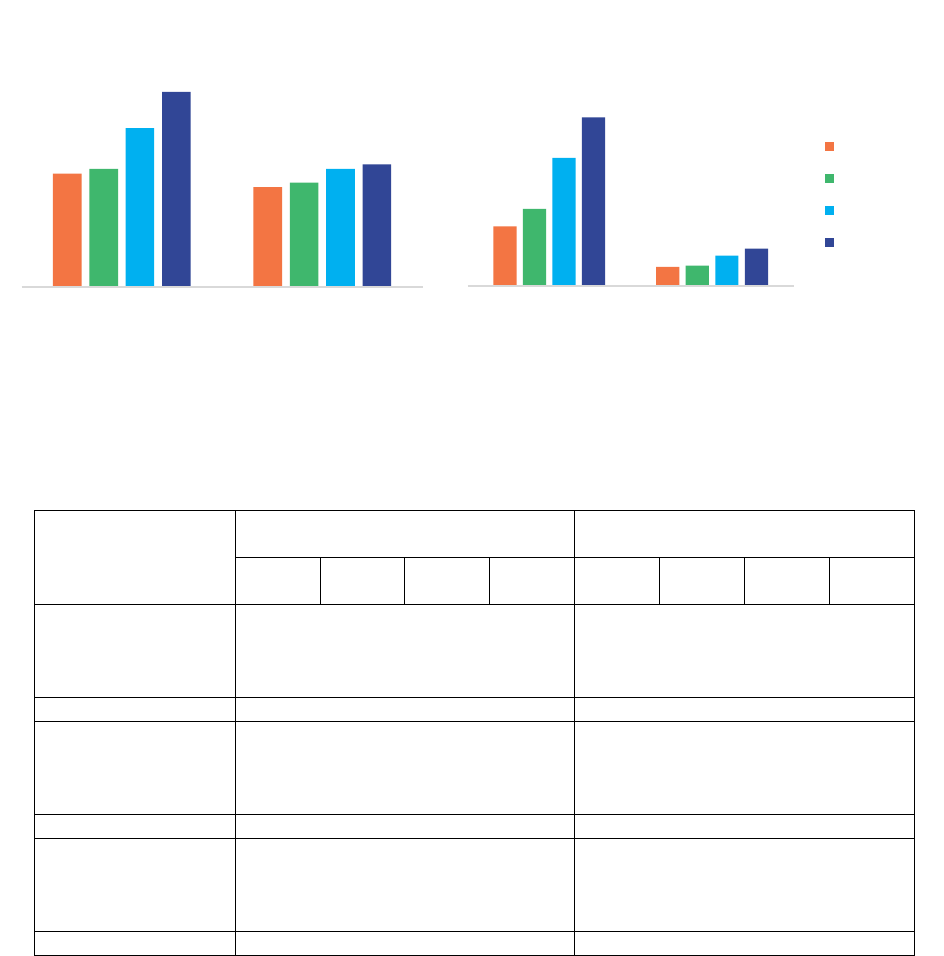

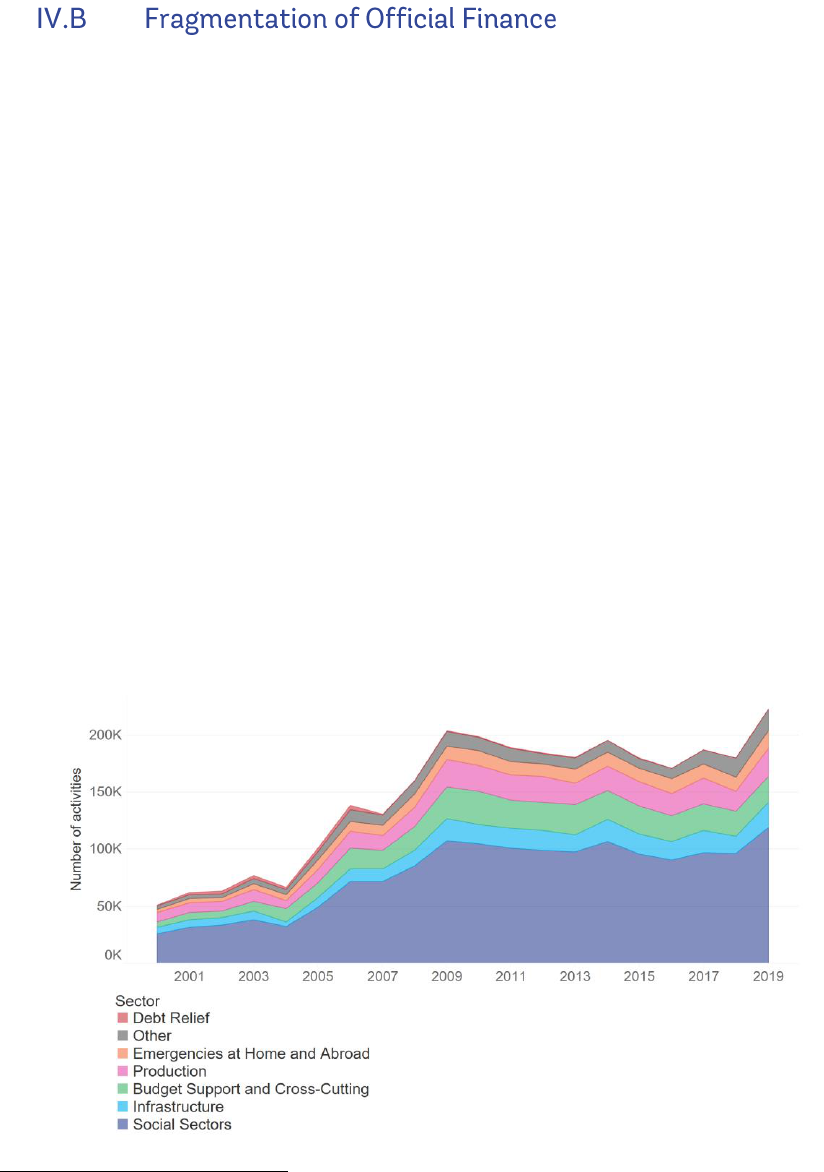

the period, more implementation by private sector institutions was reported. Delivery channels