DoDM 5110.04, Volume 1, June 16, 2020

SECTION 6: WRITING STYLE AND PREFERRED USAGE 24

SECTION 6: WRITING STYLE AND PREFERRED USAGE

6.1. GENERAL GUIDELINES.

Whether writing a memorandum for SecDef information or action or drafting a letter for SecDef

signature, DoD correspondence must adhere to the highest standards of clarity and

professionalism in accordance with DoDI 5025.13. Because correspondence is often drafted by

persons other than the signer, it is important to consider these guidelines in the context of both

the sender and the recipient of the communication:

a. Action and Info Memoranda.

Action and info memoranda should be concise. Each memorandum objective will dictate the

length, but generally each memorandum should provide only the material necessary for action or

“bottom line up front” information; extensive background information and supporting material

should be attached. See Section 7 for guidance on structuring memoranda.

b. Correspondence for Principals’ Signature.

Regardless of the routine or customary nature of any individual piece of correspondence, all

items signed by the SecDef, the DepSecDef, or the ExecSec must be of the highest quality.

Writers must consider the signer as well as the addressee and adapt the correspondence

accordingly.

c. References.

Good writing skills develop with time, training, and experience. If specific guidance is not

provided in volume, writers must use the U.S. Government Publishing Office Style Manual,

including supplements, as the authority for answers to questions concerning punctuation,

capitalization, numerals, compound words, writing style, etc. Other possible references include

the Chicago Manual of Style and the Gregg Reference Manual as long as they do not conflict

with the U.S. Government Publishing Office Style Manual, or this issuance. Spelling is in

accordance with Merriam-Webster’s New Collegiate Dictionary.

6.2. PREPARATION.

Preparation is the first step to good writing. The writer must assess the subject, audience, and

purpose of the communication and keep these in mind throughout the writing process. These

elements of preparation are interrelated and can be assessed simultaneously:

a. Subject Line on Memoranda and Messages.

(1) In DoD memoranda and messages, the OPR may determine the subject. Clarifying

and refining the subject help the writer organize and present the most relevant information

clearly. These questions assist in refining the subject:

DoDM 5110.04, Volume 1, June 16, 2020

SECTION 6: WRITING STYLE AND PREFERRED USAGE 25

(a) What is the assignment or question?

(b) What does the audience need or want to know?

(c) How specific or general should the communication be?

(2) Action and info memoranda should be limited to a single subject. If it is necessary to

communicate information about multiple subjects, the writer should consider using separate

memoranda.

(3) The subject line should clearly communicate the subject in one or two lines. The

writer should avoid vague, one-word subjects and use instead specific descriptions that indicate

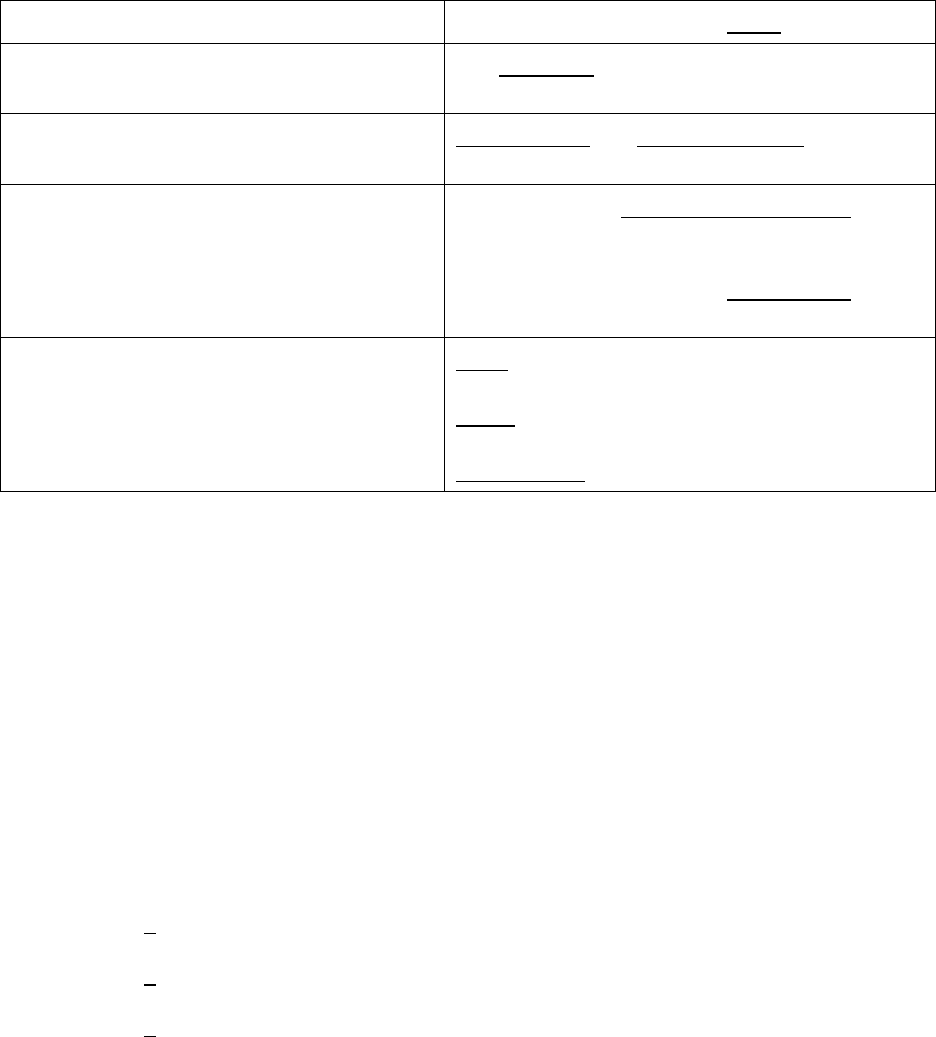

or summarize the content of the memorandum or message, as shown in Table 7.

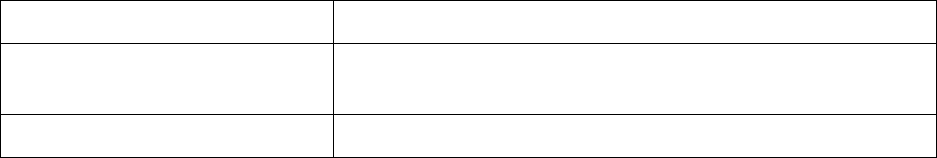

Table 7. Examples of Vague Subjects and Suggested Alternatives

Vague Subjects

Specific, Descriptive Subjects

SUBJECT: Iraq

SUBJECT: October 2018 Assessment of Iraq Provincial

Reconstruction Teams

SUBJECT: Budget Issues

SUBJECT: Budget Projections for Fiscal Year 2018

b. Audience.

(1) Official DoD correspondence should have a specific audience. Determining the

audience helps tailor the message and present information in the most appropriate way. When

drafting correspondence for SecDef or DepSecDef signature, the audience may be an OSD

Component head, a member of Congress, the President of the United States, or family members

of a fallen Service member. Writers should carefully consider the audience from the perspective

of the signer.

(2) These questions assist in determining the audience:

(a) Who will read this communication?

(b) What is the signer’s relationship to the audience?

(c) What does the audience already know about this subject?

(d) What tone should be used to address this audience (e.g., formal, informal)?

c. Purpose.

(1) DoD official correspondence must have a specific purpose. Like the subject of a

memorandum or message, the purpose of correspondence may be determined by an assignment

or initiated by the generating organization. Common purposes include:

(a) Providing options or recommendations.

DoDM 5110.04, Volume 1, June 16, 2020

SECTION 6: WRITING STYLE AND PREFERRED USAGE 26

(b) Requesting authorization.

(c) Reporting or summarizing information.

(d) Evaluating, analyzing, or interpreting data.

(2) These questions help refine the purpose:

(a) What is the aim of the assignment?

(b) What must this communication accomplish?

(c) How can its purpose best be achieved?

6.3. ORGANIZATION, CLARITY, AND STYLE.

DoD correspondence must neither be so brief that it lacks clarity, nor so wordy that it clouds

rather than illustrates the message. There is no one-size-fits-all formula for writing style; a

meeting summary will be different in style than a letter of condolence. By applying the basic

principles of organization and clarity, a writer can communicate the essential information clearly

and completely, in a style most appropriate to the message.

a. Organization.

The organization of a document should flow logically from refinement of the subject,

audience, and purpose. The organizational scheme should fit the subject and purpose and ideas

should be organized according to the scheme.

(1) Common Organizational Schemes.

(a) Chronological.

Arrange events in sequential order, from first to last.

(b) Systematic.

Arrange events, people, or things according to their placement in a system or process.

(c) C&R (or problem and solution).

Provide background information and evaluate a situation; then provide one or more

options or recommendations for future action.

(d) General to Specific.

Arrange by main point or points and fill in supporting details, examples, and

illustrations.

DoDM 5110.04, Volume 1, June 16, 2020

SECTION 6: WRITING STYLE AND PREFERRED USAGE 27

(2) Outlining.

See Volume 2 of this manual for information on using an outline to develop the

organizational scheme.

(3) Transitions.

Transitional phrases are used to highlight organization, to facilitate the flow of writing

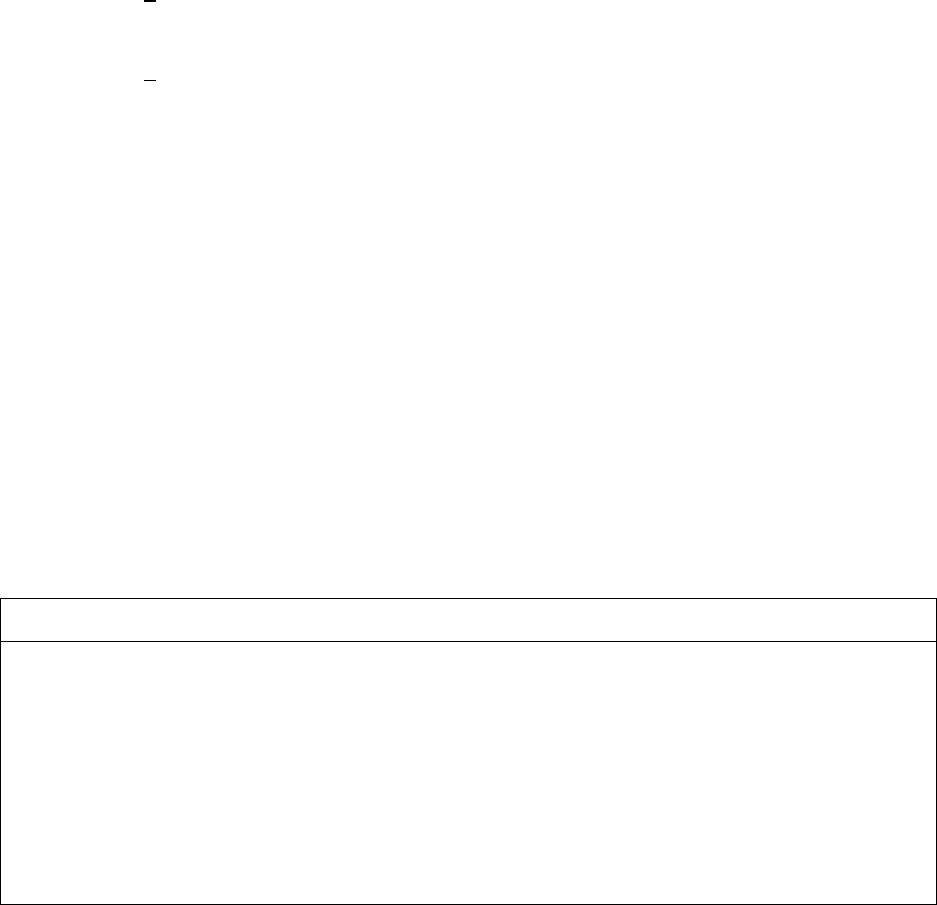

from point to point, and to improve clarity and readability. Table 8 provides a list of transitional

phrases and their uses.

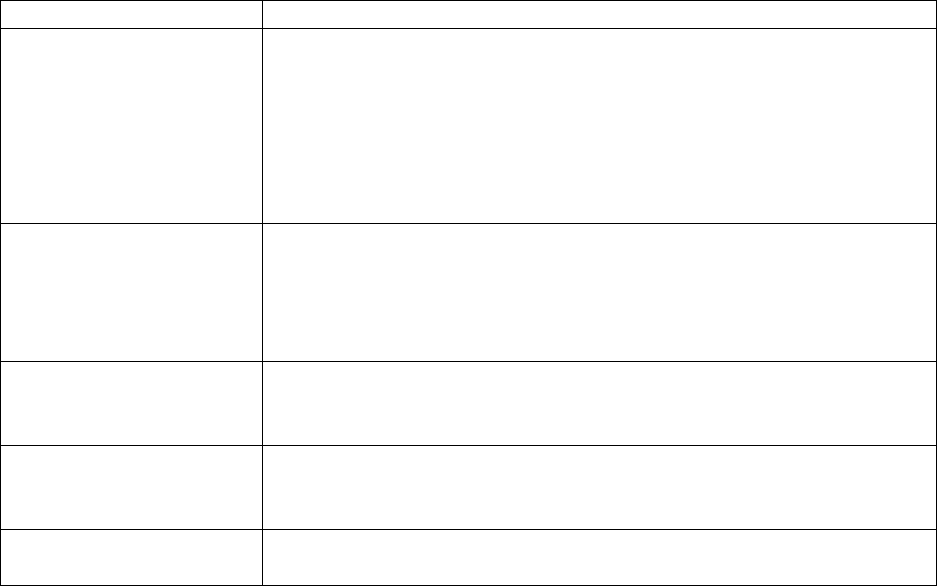

Table 8. Transitional Words and Phrases

Use

Transitional Words and Phrases

Time or Sequence

–

–

first, second, third...

first, next, last...

–

–

–

–

–

once, then, finally

again, also, and

afterward, following, at length, since

before, formerly, lately

now, meanwhile, currently, simultaneously

Comparison or Contrast

–

–

–

–

likewise, similarly, in the same way

but, yet, however, nevertheless, while, still

despite, in spite of, regardless, in contrast

on one hand, on the other hand

– instead, on the contrary, otherwise

Illustration or Expansion

–

–

–

for example, for instance

moreover, furthermore, namely

incidentally, indeed, in fact

Summary or Conclusion

–

–

in conclusion, in summary

to conclude, to summarize

– therefore

Cause or Effect

–

–

as a result, consequently, since

accordingly, because, therefore

(4) Bullets.

Bullets provide a simple format for structuring main ideas or listing supporting ideas,

concepts, items, or steps. They facilitate efficient communication by marking portions of text to

indicate divisions and relationships among concepts within a communication. See Sections 7

and 8 for examples of bullets in DoD correspondence.

(a) Bullets for Main Ideas.

Bullets should be used to illustrate main ideas in standard, action, and info

memoranda, except that they may not be used for main ideas in letters or memoranda for SecDef

or DepSecDef signature. One bullet should be used for each paragraph. Transitional words

DoDM 5110.04, Volume 1, June 16, 2020

SECTION 6: WRITING STYLE AND PREFERRED USAGE 28

(“moreover,” “finally,” etc.) should not be used to lead off bullets if their use would be

redundant.

(b) Bullets for Supporting Ideas.

If it would facilitate communication, bullets and sub-bullets within bulleted

paragraphs may be used to illustrate significant supporting ideas that relate directly to the main

idea. Complete sentences should be used to express supporting ideas. Bullets and sub-bullets

should be avoided if the ideas are simple enough to be stated clearly in the text of the paragraph

or would be more clearly expressed by use of transitional phrases.

(c) Bullets for Lists.

Bullets may be used to list concepts, items, or steps when the list is ordinal or

sequential. There must be at least two items in the list. An introductory phrase should present

the points that follow, and each bullet should begin with the same type of word (e.g., a verb or a

noun) in the same tense and voice.

b. Clarity and Style.

Because of the nature of the DoD mission, clarity is of utmost importance in DoD

communication. Clarity may be achieved by identifying the actors in the text and clearly linking

them to specific, meaningful actions. Asking the question, “Who does what?” helps identify

actors and actions.

(1) Active Versus Passive Voice.

One major obstacle to clear communication is excessive use of passive voice. See Table

9 for examples of active and passive voice.

(a) Active Voice.

Normal English sentence structure follows the actor – action – object pattern, or “who

does what to whom.” For example, “Bill (actor) gave (action) Jimmy (object) the car (object).”

(b) Passive Voice.

The passive voice substitutes the actor with the object, using the verb “to be” and a

past participle. For example, “The car was given to Jimmy” or “Jimmy was given the car.” The

passive voice lacks clarity because it does not identify the actor.

(c) Exceptions.

In some situations, the passive voice is necessary or preferable to the active voice.

Generally, however, use of the active voice produces greater clarity because it states who does

what, usually in fewer words.

DoDM 5110.04, Volume 1, June 16, 2020

SECTION 6: WRITING STYLE AND PREFERRED USAGE 29

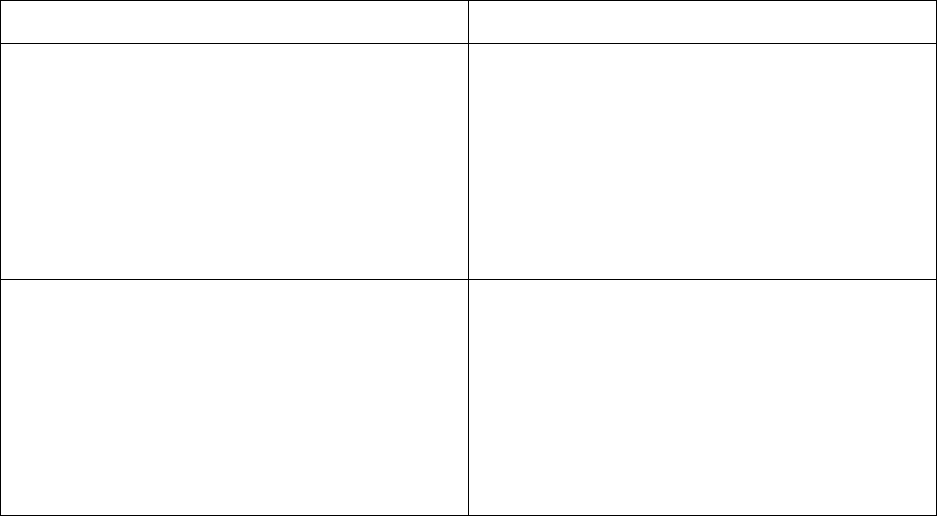

Table 9. Examples of Passive Voice and Suggested Alternatives

Passive Voice

Active Voice

Frequently omits the doer of the action.

An information copy of the board meeting

minutes must be forwarded to the members.

A military chaplain of a particular religious

organization may be appointed as a

consultant.

Identifies the doer.

The Chair must forward an information copy

of the board meeting minutes to the members.

The Board may appoint a military chaplain of

a particular religious organization as a

consultant.

Frequently is longer and less direct;

frequently includes a “by” phrase.

A written agreement will be executed by the

parties.

Implementing instructions will be issued by

the DoD Components

Gets to the point.

The parties execute a written agreement.

The DoD Components issue implementing

instructions.

(2) Weak Verb Phrases.

Writers should use strong, simple, active verbs to describe specific actions, rather than

weak verb phrases that rely on the verbs “to be” or “to have” to complete the action. Such

phrases obscure meaning and result in wordy, ambiguous sentences. Writers should also avoid

the phrases “there is” and “there are,” which detach the actor from the action, resulting in vague

communication. See Table 10 for guidance on eliminating weak verb phrases.

DoDM 5110.04, Volume 1, June 16, 2020

SECTION 6: WRITING STYLE AND PREFERRED USAGE 30

Table 10. Examples of Weak Verb Phrases and Suggested Alternatives

Instead of

Weak Verb Phrases

Use

Strong Active Verbs (Actor, Action)

There were several members in attendance.

Several members attended.

It is incumbent upon each member to

ensure a POC is identified.

Each member must identify a POC.

The members were in agreement that the

policy was in need of revision.

The members agreed that the policy should be

revised.

– or –

The members agreed to revise the policy.

…made a suggestion…

…suggested…

…was desirous of…

…wanted…

…has a requirement…

…requires…

…came to a decision…

…decided…

(3) Subject-Verb Agreement.

Problems with subject-verb agreement result in confusing and sometimes embarrassing

writing. Writers must ensure that the verb of the sentence applies correctly to the subject. See

Table 11 for subject and verb guidelines.

(a) Writers may have trouble identifying problems with subject-verb agreement when

the subject and the verb are far removed from each other in a sentence.

(b) A sentence with more than one subject may require a singular or plural verb

depending on how the subjects are related.

1. Two or more subjects joined by “and” usually require a plural verb.

2. If multiple subjects are joined by “or” or “nor,” the noun closest to the verb

dictates the form. If a subject contains a singular noun and a plural noun, the plural noun should

be placed closer to the (plural) verb to enhance readability.

3. Some indefinite pronouns, when used as subjects, require only singular verbs

(e.g., “anyone,” “anything,” “each,” “either,” “everyone,” “everything,” “much,” “neither,”

“none,” “nothing,” “someone,” and “something”).

DoDM 5110.04, Volume 1, June 16, 2020

SECTION 6: WRITING STYLE AND PREFERRED USAGE 31

Table 11. Subject-Verb Agreement Guidelines

Sentence Structure

Subject-Verb Agreement (Actor, action)

Subject and verb separated by several

words: Make sure subject and verb agree.

The handbook of rules and regulations contains

[not contain] important safety information

Subjects joined by “and:” Use plural verb.

The Secretary and Deputy Secretary agree [not

agrees] on this proposal.

Subjects joined by “or:” Determined by

the subject nearest the verb.

The chairman or the committee members decide

the issue.

The committee members or the chairman

decides the issue.

Singular indefinite pronouns used as

subjects.

None of the options is viable.

Either option is viable.

Each mission requires significant resources.

6.4. CAPITALIZATION, PUNCTUATION, AND USAGE.

This paragraph provides basic instructions for standardizing English usage in DoD

correspondence; it is not exhaustive. Detailed guidance is provided in the U.S. Government

Publishing Office Style Manual.

a. Capitalization.

(1) General Rules.

(a) A common noun or adjective forming an essential part of a proper name is

capitalized; the common noun used alone as a substitute for the name of a place or thing is not

capitalized. For example:

1. Massachusetts Avenue; the avenue.

2. Committee Chair John Smith; the committee chair.

3. Defense Acquisition Guidebook; the guidebook.

(b) Capitalize titles of documents, publications, papers, acts, laws, etc. Capitalize all

principal words in titles (title case); do not capitalize definite or indefinite articles (e.g., “a,”

“an,” “the”), prepositions (e.g., “by,” “for,” “in,” “to”), or conjunctions (e.g., “and,” “but,” “if”),

except as the first word of the title. For example:

DoDM 5110.04, Volume 1, June 16, 2020

SECTION 6: WRITING STYLE AND PREFERRED USAGE 32

1. For a report title: “Secretary of Defense Annual Report to Congress on the

Activities of the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation for 2017.”

2. For a newspaper: The article appeared in “The Washington Post.”

(2) Capitalization Rules Specific to DoD Writing.

(a) Use title case for the subject line of a memorandum in accordance with Paragraph

7.2.l.

(b) Use UPPERCASE for the actual titles of military operations (e.g., “Operation

ENDURING FREEDOM,” “Operation IRAQI FREEDOM”) and for the names of the

Combatant Commands when abbreviated (e.g., “USCENTCOM,” “USINDOPACOM”).

(c) Capitalize the terms “Nation,” “Union,” “Administration,” “Confederation,”

“Commonwealth,” and “Members” only if used as part of proper names, except “Nation” is

capitalized when referring to the United States. Also capitalize “Federal” and “Government”

when referring to the United States.

(d) Do not capitalize “soldiers”, “sailors,” “airmen,” “marines,” “ally,” “allies,” and

“coalition” unless used in conjunction with a proper noun.

Table 12. Examples of DoD-Specific Capitalization

DoD-specific capitalization is bolded for emphasis in these examples:

Any nation seeks to protect its interests.

The Colonel is a national hero.

He brings great credit upon the Nation. (Referring to the United States.)

The Federal Government employs thousands of people. (Referring to the U.S. Government.)

The Agency for International Development is a Federal agency. (Referring to a U.S. Federal

agency.)

The agency works for Government reform. (Referring to the U.S. Government.)

The agency works for reform of the Haitian government.

The Chief of Staff of the Army thanked the Service member for her service.

b. Acronyms and Abbreviations.

(1) Use acronyms only when the term occurs more than once in the body of the

document.

(2) Do not use or introduce acronyms in a subject line.

(3) Write out terms as they first appear in the text and place the abbreviation or acronym

in parentheses immediately after the term. For example, “The Director of Administration and

Organizational Policy, Office of the Chief Management Officer of the Department of Defense

(DAOP OCMO) will provide policy guidance.”

DoDM 5110.04, Volume 1, June 16, 2020

SECTION 6: WRITING STYLE AND PREFERRED USAGE 33

(4) Use U.S. Postal Service abbreviations for addresses only; spell out State names in the

body of the correspondence.

(5) Spell out “United States” when used as a noun. When used as an adjective, or when

preceding the word “Government” or the name of a government organization, use “U.S.” (no

spaces). Always spell out the term “United States” when it appears in a sentence containing the

name of another country. For example:

(a) They are studying the foreign policy of the United States.

(b) The students are interested in U.S. foreign policy.

(c) The United States-Japan relationship is strong.

(6) For military rank abbreviations by Military Service and rank or pay grade, see

Volume 2 of this manual.

c. Punctuation.

(1) Apostrophe.

The apostrophe is used to show possession or to form a contraction.

(a) Do not use contractions in formal DoD correspondence; instead spell out each

word. For example, use “do not” instead of “don’t.”

(b) Use apostrophes to show possession:

1. For singular or plural nouns not ending in “s,” add “’s.” For example:

a. This is Timothy’s book.

b. I am the child’s teacher.

c. I am the children’s teacher.

2. For plural nouns ending in “s,” add an apostrophe only. For example:

a. The teachers’ proposal includes three separate provisions.

b. We must reconcile the committee members’ schedules.

3. If more than one noun possesses an object, add “ ’s” to the noun nearest the

object. For example, “I approve of George and Ted’s system” (e.g., the system belonging to

George and Ted).

4. If more than one noun possesses multiple objects, add “ ’s” to both nouns. For

example, “I approve of George’s and Ted’s systems” (e.g., George and Ted each developed

separate systems).

DoDM 5110.04, Volume 1, June 16, 2020

SECTION 6: WRITING STYLE AND PREFERRED USAGE 34

(2) Comma.

The comma is the most common form of punctuation and is used to separate elements of

a sentence, enhance readability, and improve clarity by signaling to the reader a logical break in

the flow of text. However, excessive use of commas can clutter the text. Use commas

consistently and exercise judgment in observing these guidelines:

(a) Use a comma to set off parenthetic words, phrases, or clauses, or introductory or

pertinent material. For example:

1. It is obvious, therefore, that this office cannot function.

2. In other words, the meeting was cancelled.

3. Mrs. Jones, the committee representative, conducted the meeting.

(b) Use an Oxford comma to separate items in a series of three or more. For

example:

1. The supply team provided a telephone, a computer, and a scanner.

2. Mr. Winston, Mrs. Jones, and I attended the meeting.

(c) Use a comma in numbers containing four or more digits, except in serial numbers

and dates. For example:

1. The case is OSD012345-19.

2. The estimated cost for implementation is $2,300,000.

3. The general recommended redeploying 22,000 troops.

(3) Semicolon.

(a) The semicolon, similar to but stronger than the comma, indicates a break in the

flow of a sentence and is primarily used to separate independent or coordinate clauses in the

same sentence.

(b) Use a semicolon to emphasize the close association, either in similarity or

contrast, of two clauses where separate sentences would be too strong. For example:

1. The car would not move; it was broken.

2. The meeting began well; however, several attendees arrived late.

(c) Use a semicolon to separate items in a series of three or more when the items are

lengthy or contain internal punctuation. For example, “The meeting was attended by the

Director of Administration, Office of the Chief Management Officer of the Department of

DoDM 5110.04, Volume 1, June 16, 2020

SECTION 6: WRITING STYLE AND PREFERRED USAGE 35

Defense; Director, Washington Headquarters Services; and the Chief, Correspondence

Management Division.”

(d) Avoid excessive use of the semicolon; it diminishes readability.

(4) Colon.

(a) Use a colon to join two clauses where the essence of the second clause derives so

directly from the first clause by explanation or illustration that separate sentences would weaken

the meaning. For example:

1. The directions were clear: proceed to step two.

2. An opening appeared: the team advanced.

(b) Also use a colon to introduce any matter that forms a complete sentence,

question, quotation, or list. For example:

1. The doctor gave this assessment: “The patient is doing well.”

2. We need the following items: a telephone, a computer, and a scanner.

(5) Quotation Marks.

(a) Use quotation marks to enclose direct quotations, descriptive designations, and

titles of articles and publications. For example:

1. The document was marked “SECRET.”

2. I received a copy of the report, “Defense Strategy for the 21st Century.”

3. You asked the question: “Why are the numbers so low?”

(b) Enclose needed punctuation within quotation marks unless the meaning would

otherwise be impaired. For example:

1. Punctuation within quotes: He asked, “Is this the correct copy?”

2. Punctuation outside of quotes: Can we be sure this is the “correct copy”?

(6) Punctuation Spacing.

For colons and periods, place two spaces between the punctuation and the text that

immediately follows it. For commas and semicolons, place one space between the punctuation

and the text that immediately follows it.

d. Numbers.

(1) Use numerals for single numbers of 10 or more. For example:

DoDM 5110.04, Volume 1, June 16, 2020

SECTION 6: WRITING STYLE AND PREFERRED USAGE 36

(a) The team consisted of about 40 men.

(b) The incident occurred on two separate occasions.

(2) When 2 or more numbers appear in a sentence and 1 of them is 10 or larger, use

numerals for each number (e.g., “About 40 men competed in 3 separate events.”).

(3) Spell out numbers if they begin a sentence (e.g., “Seventy-five percent of

respondents viewed the case favorably.”).

(4) Use numerals to express units of measurement, time, or money. For example:

(a) We will meet at 4 o’clock.

(b) The convoy marched 3 kilometers.

(c) Lunch will be provided for 5 dollars.

e. Dates.

(1) The preferred date format is “month day, year” (e.g., “Your February 23, 2018

memorandum clearly illustrates the policy.”).

(2) The more traditional “month day, year,” format is also acceptable (usually in more

formal communication such as letters, award citations, etc.), but should always be followed by a

comma unless it closes the sentence (e.g., “Your February 23, 2018, memorandum clearly

illustrates the policy.”).

(3) Avoid using ordinal numbers in dates (e.g., use “February 5,” not “the 5th of

February”).

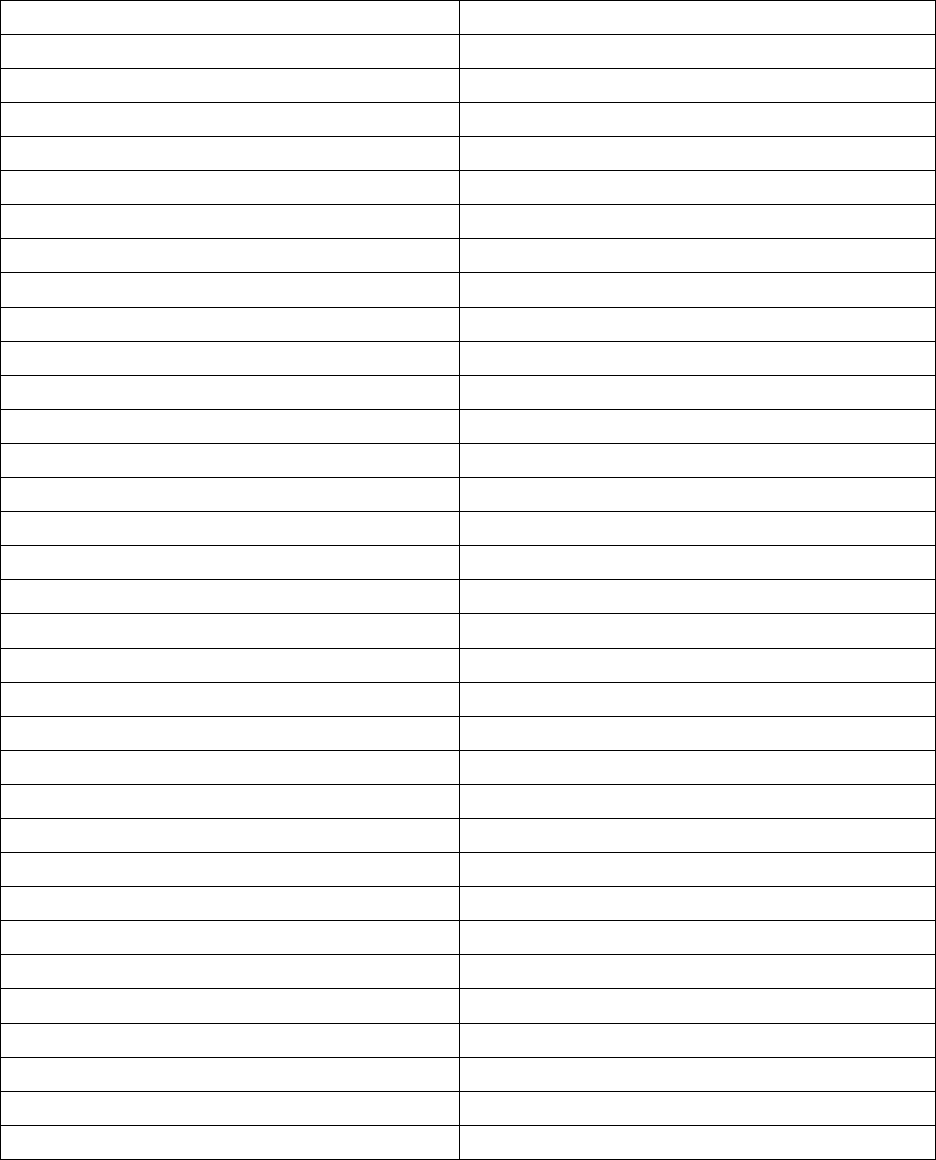

f. Commonly Confused Words.

Table 13 provides examples of words writers commonly confuse and their meanings.

DoDM 5110.04, Volume 1, June 16, 2020

SECTION 6: WRITING STYLE AND PREFERRED USAGE 37

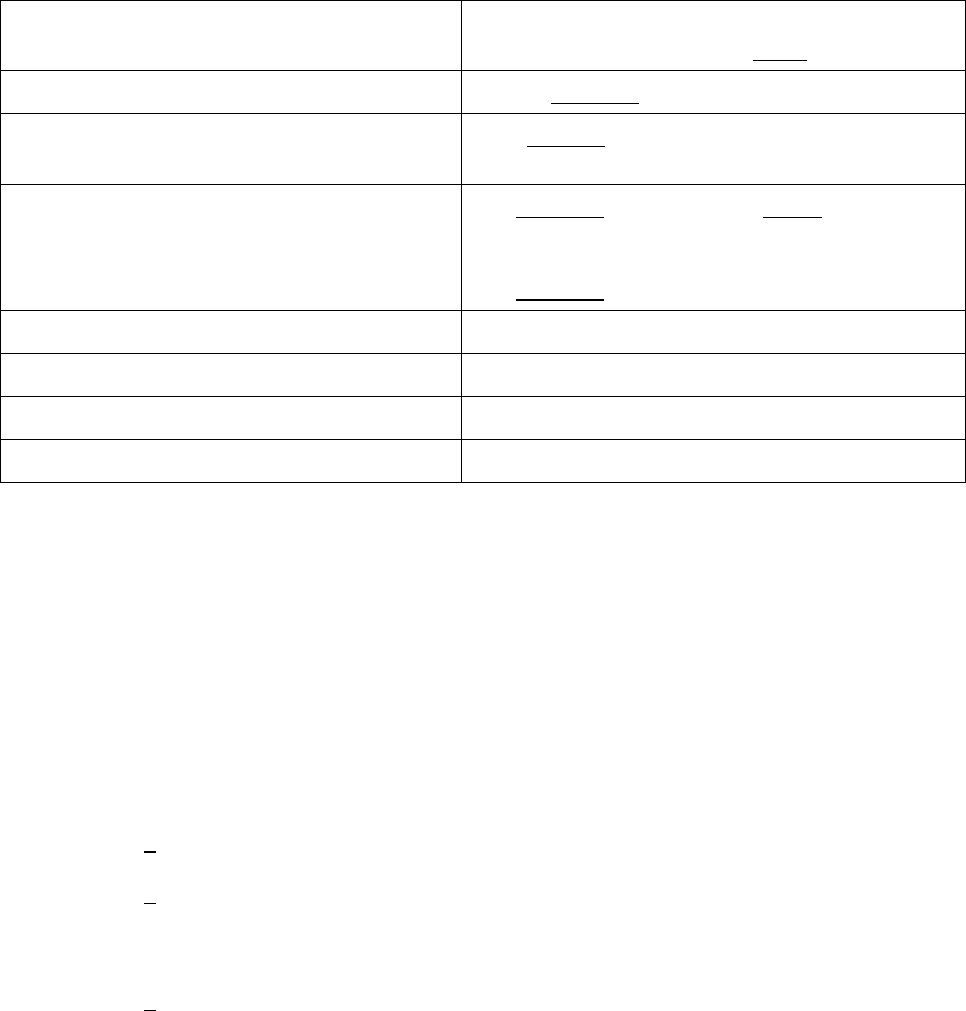

Table 13. List of Commonly Confused Words

Word

Sometimes Confused With

Accept (to receive)

Except (other than)

Advice (an opinion)

Advise (to give advice)

All ready (prepared)

Already (by this time)

Allude (to refer to indirectly)

Elude (to avoid)

Allusion (indirect reference)

Illusion (erroneous belief or conception)

Among (more than two alternatives)

Between (only two alternatives)

Ascent (a rise)

Assent (agreement)

Beside (next to or near)

Besides (in addition to)

Born (brought into life)

Borne (carried)

Brake (stop)

Break (smash)

Capital (the seat of government)

Capitol (the building where a legislature meets)

Cite (to quote an authority)

Site (a place)

Compliment (praise)

Complement (completes)

Continually (closely recurrent intervals)

Continuously (without pause or break)

Council (a group)

Counsel (to give advice)

Descent (a movement down)

Dissent (disagreement)

Desert (to abandon)

Dessert (a course after dinner)

Discreet (reserved, respectful)

Discrete (individual or distinct)

Elicit (to bring out)

Illicit (unlawful)

Farther (expresses distance)

Further (expresses degree)

Formally (conventionally)

Formerly (in the past)

Imply (to hint at or suggest)

Infer (to draw a conclusion)

Insure (to procure insurance on)

Ensure (to make certain)

Lay (to place)

Lie (to recline, stretch out)

Lessen (to make less)

Lesson (something learned)

Moneys (currency)

Monies (amount of money)

Morale (a mood)

Moral (right conduct)

Principal (most important)

Principle (basic truth or law)

Raise (to build up)

Raze (to tear down)

Stationary (unmoving)

Stationery (writing paper)

Their (belonging to them)

There (the opposite of here)

To (toward)

Too (also)

Who (refers to people)

Which (refers to things)